Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

Court of Appeal in Northern Ireland Decisions

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> Court of Appeal in Northern Ireland Decisions >> Duff, Application for Judicial Review [2024] NICA 42 (03 April 2024)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/nie/cases/NICA/2024/42.html

Cite as: [2024] NICA 42

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

|

Neutral Citation No: [2024] NICA 42

Judgment: approved by the court for handing down (subject to editorial corrections)* |

Ref: TRE12475

ICOS No: 21/055065

Delivered: 03/04/2024 |

IN HIS MAJESTY’S COURT OF APPEAL IN NORTHERN IRELAND

___________

ON APPEAL FROM THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE IN NORTHERN IRELAND KING’S BENCH DIVISION (JUDICIAL REVIEW)

___________

IN THE MATTER OF AN APPLICATION BY GORDON DUFF

(RE GLASSDRUMMAN ROAD, BALLYNAHINCH) FOR JUDICIAL REVIEW

AND IN THE MATTER OF A DECISION OF NEWRY, MOURNE AND DOWN DISTRICT COUNCIL

___________

The appellant, Mr Duff, appeared in person

Philip McAteer (instructed by Belfast City Council Legal Services Department) for the Respondent

William Orbinson KC and Fionnuala Connolly (instructed by O’Hare Solicitors) for the Notice Party, Mr Carlin

Stewart Beattie KC and Philip McEvoy (instructed by Cleaver Fulton Rankin, Solicitors) appeared and intervened (by written submissions only) for Lisburn and Castlereagh City Council

___________

Before: Keegan LCJ, Treacy LJ & Sir Paul Maguire

___________

TREACY LJ (delivering the judgment of the court)

Introduction

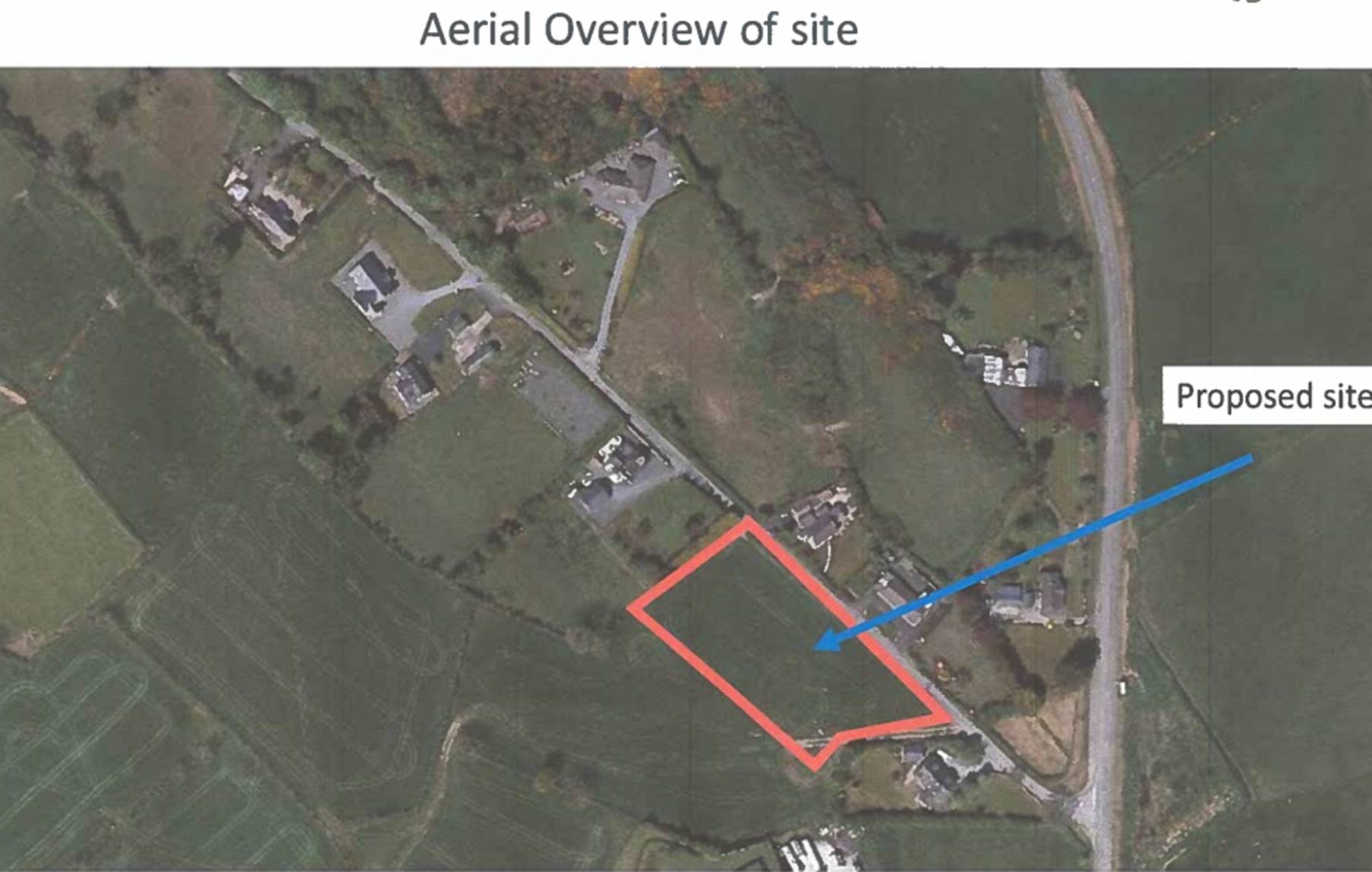

[1] In these proceedings Mr Gordon Duff, a litigant in person (“the appellant”), appeals against the decision of Scoffield J dismissing his judicial review against a decision to grant outline planning permission for two detached ‘infill’ dwellings and garages at lands located between Nos 2 and 10 Glassdrumman Road, Ballynahinch. The impugned decision was made by Newry, Mourne and Down District Council, (“the Council”) on 9 April 2021 under planning reference LA07/2020/1292.

The Main Issue

[2] The appellant’s core complaint is that the decision to allow this development will have the effect of extending ribbon development and that this is contrary to planning policy in Northern Ireland (NI). He asserts that planning policy considers ribbon development in rural areas to be damaging and unacceptable in principle, and that it requires planning applications which would cause or add to ribbon development to be rejected unless they come within the very limited exceptions described within the policies themselves. He claims the Council’s decision that this application did satisfy the conditions of the ‘small gap’ exception contained in Policy CTY8 is unsupported by the facts and wrong in law, and that therefore it should be quashed.

The relevant planning policies

Policy CTY8 within PPS21 - Ribbon development

[3] The key policy for present purposes is Policy CTY8 of PPS21. The crux of the policy is contained within the first sentence:

“Planning permission will be refused for a building which creates or adds to a ribbon of development.” [our emphasis]

[4] This is in materially similar terms to the guidance contained in Policy CTY14 on the same issue. It provides:

“A new building [in the countryside] will be unacceptable where … it creates or adds to a ribbon of development (see Policy CTY8) …” [our emphasis]

[5] The reasons for this prohibition on ribbon development are explained in the justification text related to Policy CTY8 as follows:

“Ribbon development is detrimental to the character, appearance and amenity of the countryside. It creates and reinforces a built-up appearance to roads, footpaths and private laneways and can sterilise back-land, often hampering the planned expansion of settlements. It can also make access to farmland difficult and cause road safety problems. Ribbon development has consistently been opposed and will continue to be unacceptable.” [our emphasis]

[6] Similarly, paragraph 5.80 of PPS21 states:

“It is considered that ribbon development is always detrimental to the rural character of an area as it contributes to a localised sense of build-up and fails to respect the traditional settlement pattern of the countryside.” [our emphasis]

[7] The strong, unambiguous language used in the policies just quoted shows that the policy intention was that planning permission “will be refused” for any building which would create or add to a ribbon of development. This prohibition is subject only to the limited exceptions that are built into CTY8 itself.

[8] In this case the respondent accepts that the development in this planning application would constitute ribbon development, but it claims that it came within the ‘small gap’ exception in policy CTY8. It contends that it applied the governing policy to this application and decided that the development could be allowed under the exception. It does not contend that it consciously departed from the policy on any proper planning grounds, and it is notable that no such grounds were proposed or advanced by any of the parties.

[9] This is therefore a case which turns exclusively on the issue of whether the applicable policies were correctly understood and applied by the decision maker. This means that, unless the exception is shown to have been truly available to the Council on the facts of this case, then permission must be refused because ribbon development like this is unacceptable under the policy guidelines unless it falls within a permitted exception.

The ’small gap’ exception

[10] Policy CTY8 contains limited exceptions to the prohibition against ribbon development including the so-called “small gap” exception which is the one relied upon in this case. It is expressed as follows:

“An exception will be permitted for the development of a small gap site sufficient only to accommodate up to a maximum of two houses within an otherwise substantial and continuously built up frontage and provided this respects the existing development pattern along the frontage in terms of size, scale, siting and plot size and meets other planning and environmental requirements. For the purpose of this policy the definition of a substantial and built up frontage includes a line of 3 or more buildings along a road frontage without accompanying development to the rear.”

[11] Where it is established that such a gap exists, it may be filled by an appropriate housing development, provided the requirements in relation to matters such as scale and design are also met in full.

[12] An exception to the prohibition against ribbon development can only be established if all of the conditions underpinning the exception are made out. Absent fulfilment of any of these conditions, the very closely defined exception cannot be made out. In construing and applying the exception, the decision-maker must bear in mind the inherently restrictive nature of the policy, the principal aim of which is to prevent the spread of ribbon development in rural areas.

Other relevant policies.

The Strategic Planning Policy Statement

[13] The Strategic Planning Policy Statement for Northern Ireland (SPPS) at paragraph 6.73 states:

“Infill/ribbon development: provision should be made for the development of a small gap site in an otherwise substantial and continuously built up frontage. Planning permission will be refused for a building which creates or adds to a ribbon of development; …”

There was some debate before Scoffield J about whether this paragraph altered the position set out in Policy CTY8 by referring to “provision” being made for the development of small gap sites, rather than referring to such sites as an “exception” to the general rule. In agreement with the trial judge, we do not discern any conflict between the SPPS and the more detailed policy set out in Policy CTY8 (and Policy CTY14). Nothing suggests that there was any intention in the SPPS to change policy and we do not consider that the SPPS was intended to herald any move away from the approach required by careful application of the clear terms of Policy CTY8 itself. On the contrary, the core guidance in CTY8 is reiterated in the last sentence of this paragraph confirming that the policy objective is the same in both documents.

Policy NH5 of PPS2

[14] The appellant also relied upon Policy NH5 of PPS2 on Natural Heritage. Policy NH5, entitled ‘Habitats, Species or Features of Natural Heritage Importance’, provides as follows:

“Planning permission will only be granted for a development proposal which is not likely to result in the unacceptable adverse impact on, or damage to known:

· priority habitats;

· priority species;

· active peatland;

· ancient and long-established woodland;

· features of earth science conservation importance;

· features of the landscape which are of major importance for wild flora and fauna;

· rare or threatened native species;

· wetlands (includes river corridors); or

· other natural heritage features worthy of protection.

A development proposal which is likely to result in an unacceptable adverse impact on, or damage to, habitats, species or features may only be permitted where the benefits of the proposed development outweigh the value of the habitat, species or feature.

In such cases, appropriate mitigation and/or compensatory measures will be required.”

[15] This policy is relevant because hedgerows are a known priority habitat in NI and it was known that the grant of this application would necessarily trigger ‘damage’ to a significant stretch of hedgerow. The likely effects of the development proposal on the established hedgerows on this site was therefore a factor that the decision maker ought to have considered very carefully when deciding the application.

Factual and procedural background

[16] The planning application is for two detached infill dwellings and garages at lands located between Nos 2 and 10 Glassdrumman Road, Ballynahinch. According to the report provided to the Council’s Planning Committee by its professional planning officers, (“the officers’ report”), the application site is 0.47ha and comprises the front portion of a field which lies between the two properties mentioned. There is mature vegetation along the roadside boundary. The surrounding land is predominantly domestic and agricultural in use, with a number of dwellings along the immediate stretch of road. The site is located within the rural area, outside any designated settlement areas.

[17] The planning application was advertised in the local press on 30 September 2020 and the usual neighbour notification was carried out. Eighteen objections were received including three from elected members of the Council and one from the appellant in this case.

[18] The appellant first objected to the planning application by way of letter dated 30 September 2020 which was exhibited to his grounding affidavit. The Planning Committee of the Council ‘called in’ the application to be determined by it. It was dealt with at the Committee’s meeting of 16 December 2020. As is usual, the officer’s report on the application was presented to the Committee. The appellant was granted speaking rights at the meeting, and he presented his arguments which were in similar terms to those set out in his letter of objection. He also argued that the Committee could not properly decide this application without having visited the site. The Committee put that suggestion to a vote and determined that it was not in favour of having a site visit. The Committee also voted on the substance of the planning application. It voted to approve the application by eight votes in favour and two votes against.

[19] The appellant sent pre-action correspondence to the Council the day after the Committee’s decision, on 17 December 2020. The Council did not respond in substance to the pre‑action correspondence but rescheduled the application for further consideration before the Planning Committee on 8 April 2021.

[20] Before this meeting occurred, the planning officer prepared and presented an addendum to his original report. This addendum did not mention Mr Duff’s pre‑action correspondence. It related to issues of flood risk and historic interests which had arisen separately.

[21] The application was considered again by the Committee on 8 April 2021. Before this meeting, on 26 March, the appellant submitted a short statement for the benefit of the Committee. At this meeting the Committee considered the matter again and heard from the planning applicant’s agent (Mr Carlin) and from the appellant. The Committee once again voted to approve the application (with eight members voting in favour; none against; and one abstention). The planning permission was issued on 9 April 2021. The appellant thereafter sent further pre‑action correspondence to the Council but also issued his application for leave to apply for judicial review on 8 July 2021 in order to comply with the time limit in RCJ Order 53, rule 4.

How were the relevant policies applied by the decision maker?

[22] As noted above, the key question in this case is whether or not the ‘small gap’ exception to policy CTY8 was made out in this case. At the meetings with the Planning Committee this issue was addressed by both the Council’s planning officers and by the appellant.

The planning officer’s report

[23] The officer’s report correctly identified the relevant policies and supplementary guidance that had to be considered. The core elements of Policy CTY8 were summarised for the Committee.

[24] An assessment of the application against the policy guidelines was carried out by a case officer and approved by a senior planning officer, as well as the file being reviewed by the Council’s Chief Planning Officer in advance of the relevant Committee meetings. The officer’s assessment of whether the proposed site was a small gap site within a substantial and continuously built-up frontage was as follows:

“The proposed [development] site has a frontage of 111m onto the Glassdrumman Road. To the south east of the site lies No 2 which is a dwelling with detached garage, both with frontage onto the road. To the north west of the site is a dwelling at No 10 also with frontage to the road. Further along the road lies a ménage which is in association with No 12 Glassdrumman Road and two further dwellings beyond, with frontage to Glassdrumman Road. Officers are satisfied that the site comprises a small gap site within a substantial and continuously built up frontage.”

[25] The trial judge summarised the appellant’s points in opposition to the officer’s report and we gratefully adopt that summary here. The appellant’s main contentions were:

(1) the approved sites are not within a substantial and continuously built-up frontage;

(2) the gap which is to be infilled is not small;

(3) No 12 Glassdrumman Road does not have a frontage to that road;

(4) a number of policies prohibit creation of, or addition to, ribbon development, in which the approval of this planning application results, and he asserts that this is an absolute prohibition.

(5) the Planning Committee fell into error or acted unlawfully in failing to conduct a site visit in this case;

(6) there are issues about the removal of hedgerows which will be required by the implementation of the impugned permission, and these issues were not considered adequately or at all by the decision maker.

The appellant’s grounds of judicial review

[26] When leave was granted, the pleaded grounds were significantly refined so that there were only three grounds of challenge to be addressed by Scoffield J, namely (i) illegality; (ii) the leaving out of account of material considerations; and (iii) irrationality. These challenges were framed as follows:

“Illegality

“... [T]he respondent erred in law in its interpretation of Policy CTY8 and/or CTY14 of PPS21 and/or of paragraph 6.73 of the SPPS [Strategic Planning Policy Statement] and thereby failed to apply them properly or at all.”

Material considerations

“… [T]he impugned decision is vitiated because the respondent wrongly left out of account the following considerations:

· relevant supplementary planning guidance in ‘Building on Tradition’; and

· the extent of hedgerow removal involved in the proposed development and/or Policy NH5 of PPS2 in relation to hedgerows.”

Irrationality

“… [T]he respondent’s view that Policy CTY8 was complied with was irrational in the Wednesbury sense in that the respondent wrongly:

· considered there to be a “substantial and continuously built-up frontage” at the site;

· considered the ‘gap’ to be infilled to be a “small” gap;

· considered that permitting the development would not amount to creating or adding to ribbon development; and

· reached its view on this issue without properly informing itself of material considerations by conducting a site visit to the application site.”

[27] The respondent’s case is based on two building blocks:

(i) that the proposed development site is a “small gap”, and

(ii) that this small gap falls within a substantial and continuously built up frontage.

These two propositions are reflected in the planning officer’s report.

Discussion

Is it a “small gap site” within a “continuously built-up frontage”?

[28] The central question in this case is whether the Council properly directed itself in relation to whether this planning proposal did or did not come within the terms of the small gap exception.

[29] The exception provides:

“An exception will be permitted for the development of a small gap site sufficient only to accommodate up to a maximum of two houses within an otherwise substantial and continuously built up frontage and provided this respects the existing development pattern along the frontage in terms of size, scale, siting and plot size and meets other planning and environmental requirements. For the purpose of this policy the definition of a substantial and built up frontage includes a line of 3 or more buildings along a road frontage without accompanying development to the rear.”

The small gap exception under Policy CTY8 may be available where a small gap exists ‘within an otherwise substantial and continuously built up frontage (‘SCBUF’). The approach of the trial judge was to ask first whether there is SCBUF and then ask whether there is a small gap site within that frontage, and we adopt the same approach here.

[30] The definition of a SCBUF contained in CTY8 is as follows:

“For the purpose of this policy the definition of a substantial and built up frontage includes a line of 3 or more buildings along a road frontage without accompanying development to the rear.”

[31] Policy CTY8 refers to a small gap site within an otherwise substantial and continuously built up frontage, that is to say, a road frontage which is continuously built up but for the gap which is under consideration as a development site. In the court below, whether or not an SCBUF existed was treated as a question of planning judgment, however that judgment must be informed by the physical facts that exist in the relevant area of land. ‘Planning judgment’ cannot erase observable facts.

[32] To be a ‘substantial built-up frontage’ the area in question must consist of a ‘line of 3 or more buildings along a road frontage …’ The presence of a ‘building’ is therefore essential if a plot of land is to be considered ‘built-up.’

[33] The physical features of the relevant part of the Glassdrumman Road were described as follows in the planning officer’s report:

“To the south-east of the site lies No.2 which is a dwelling with detached garage both with frontage onto the road.”

[34] Next in the ‘line’ comes the proposed development site with 111m of road frontage and, obviously, no buildings. This is the physical and visual ‘gap’ which is the subject of the proceedings.

[35] Next in the line is ‘a dwelling at No 10, also with frontage to the road.’ So far, therefore, the pattern of development is ‘building - gap - building’.

[36] After No. 10 the report says this:

‘Further along the road lies a manège which is in association with No 12 Glassdrumman Road.’

[37] A ‘manège/(‘manège’) is a piece of ground used to train horses. It can be either indoor or outdoor. The manège at No. 12 is an outdoor one and is not contained in any building. Physically it is a piece of ground with a hard surface. Visually it is a gap without a building. It is a visual gap in the line of development and it breaks the continuity of the ‘line’ of development.

[38] It is also notable that the officer’s report does not state that No. 12 has frontage to Glassdrumman Road. Rather it says:

“No 12 has a plot width of 68m … While a large portion of this frontage width is occupied by a manège, this is viewed to be in association with the domestic property at No 12 rather than being considered undeveloped land given the fencing and hardstanding and therefore is counted as part of the frontage width.”

[39] For his part, the appellant claims that No. 12 does not have frontage to Glassdrumman Road.

Requirements of the small gap exception

[40] The small gap exception is concerned with lines of development along a road frontage - in this case, along the Glassdrumman Road. To qualify for the benefit of the exception the minimum requirement is a pre-existing ‘line of 3 or more buildings along a road frontage …’

[41] The development pattern along the relevant part of Glassdrumman Road does not appear on the facts to meet this requirement. The pattern is: No. 2 - gap - No. 10 - manège gap with no building - No. 12 on the other side of the second gap. In this case there are three buildings separated by two significantly sized visual gaps. Neither gap carries any building. In these circumstances the applicant seeking planning permission cannot show a pre‑existing line of ‘continuous’ development. This ‘line of development’ is not ‘continuous’: it is punctuated by two gaps.

Was the proposed development site a ‘small gap’?

[42] Whether or not the proposed development site is a ‘small gap’ for the purposes of the exception depends on the proportions of the gap in relation to the proportions of the built-up areas of the alleged SCBUF.

[43] The officer’s report addressed plot size as follows:

“With regard plot size, No. 2 Glassdrumman Road has a plot width of 46m, No. 10 has a plot width of 54m and No 12 has a plot width of 68m. While a large portion of this frontage width is occupied by a ménage, this is viewed to be in association with the domestic property at No 12 rather than being considered undeveloped land, given the fencing and hardstanding and therefore is counted as part of the frontage width. The average of these three plot sizes is 56m. The site subject of this application has a frontage width of 111m. As there would be two dwellings within this application site, they would both have a plot width of 55.5m.

Officers are therefore satisfied that the proposed plot sizes would be in keeping with the development on either side. The proposal therefore respects the existing development pattern along this stretch of the Glassdrumman Road.

While it is acknowledged that building-to-building distance is greater than the average plot width, from a visual perspective on the ground it is considered that the site frontage and the lands outlined in red are large enough to accommodate 2 dwellings which respect the existing development pattern.

Officers are satisfied that the site comprises a small gap site within a substantial and continuously built up frontage.”

[44] In our view there is a fundamental error in this approach to evaluating smallness. The report treats the manège gap as if it is an area of developed road frontage. To be treated in this way the definition of a SCBUF within the exception requires the land to be ‘built-up.’ The photograph at appendix 1 shows that there is no building on this significant part of the road frontage and that therefore for the purposes of the small gap exception the manège section is a clear visual gap.

[45] Despite the fact that no building exists on this gap, the officer’s report includes the manège portion of the land as part of the road frontage measurement for No. 12 Glassdrumman Road. Approaching it in this way gives No. 12 a ‘developed’ frontage measurement of 68m - significantly wider than the frontages of the two other houses under consideration in this case. By including the manège gap with its lack of any building in the area of land treated as ‘developed land’, the report creates the impression that, proportionately, the application site is ‘small’ in relation to the total linear length of the developed section. This treatment of the manège gap is unsustainable and Wednesbury irrational.

[46] If our finding in relation to the absence of a SCBUF is wrong, the fact remains that the officer’s report does not specify the width of the manège gap. It simply notes that a ‘large proportion’ of the frontage width attributed to No.12 ‘is occupied by a manège.’ Had the planning officers provided the exact measurement of this piece of frontage in its report it would have been open to the decision maker to subtract that figure from the total measured length of the truly ‘built-up’ frontage, and this might well have impacted on the Council’s assessment of the issue of relative ‘smallness’ of the application site.

[47] The answer to the question ‘is this a small gap?’ could have been very different if all the relevant information had been included in the officer’s report. It was not, and this omission materially hampered the capacity of the decision maker to reach an independent judgment on the smallness or otherwise of this alleged ‘small gap’ site.

[48] For all these reasons we consider that the Council’s decision that this was a small gap site cannot stand.

[49] The appellant asserted that the grant of planning permission in this case failed to have regard to:

· the supplementary planning guidance in the ‘Building on Tradition’ document, and

· policy NH5 in relation to the removal of hedgerows.

[50] The trial judge rehearsed the rival arguments of the parties who placed reliance on the guidance in Building on Tradition and stated that:

“Both parties in this case have made the mistake of using the guidance in Building on Tradition in a mechanistic or arithmetical way to seek to support their position, when this guidance was never intended to be used as a scientific formula to produce a firm result on what is ultimately a matter of judgment. Mr Duff argues that the gap is the gap between the relevant buildings (here, the domestic properties at Nos. 2 and 10 respectively) and that that gap is wider than two times the average plot width. That requires refusal, he suggests. The Council focuses on the plot width of the new houses and say that they are (just) less than the average plot width of the houses forming the rest of the ribbon, which therefore points to grant, it suggests. Both approaches are too rigid bearing in mind the nature of the exercise and the purpose and nature of the guidance in Building on Tradition.”

[51] We agree that the guidance in policy documents should not be used as a scientific formula designed to produce a firm result. However, the mathematical indicators provided in the guidance do have value because they seek to focus attention on the relative proportions of the visual elements within a rural landscape and to clarify how these proportions relate to each other to produce the visual impression that a landscape is continuously developed in a way that suits an urban place or is less developed as is appropriate for rural landscapes.

[52] While these indicators are not exact tools, nevertheless they can and should help inform planners and decision makers so they can avoid misconstruing a landscape. Conversely, they can help decision makers to identify what it is they should keep in order to preserve the existing visual balance within a rural landscape - such as undeveloped gaps. These guidelines should not be manipulated with a view to achieving a desired number that will facilitate or frustrate any given planning outcome.

[53] In short, the foundational planning policies and the supplementary guidance, complete with its numerical guidelines, should be viewed as a toolkit to help planners identify where pre-existing ribbon development is present and where it is absent. The guidance is intended to help them correctly identify the ‘small gap’ sites within the areas of pre-existing ribbon development which can be developed as infill sites without substantially adding to the visual damage that has already been done in such cases. They are also designed to help planners identify and preserve the undeveloped truly ‘rural’ landscapes which the policy strives to maintain, so that the acknowledged damaging effects of ribbon development do not spread to new and presently uncontaminated places.

Importance of maintaining visual breaks

[54] Para 5.34 of PPS21 states that:

“Many frontages in the countryside have gaps between houses or other buildings that provide relief and visual breaks in the developed appearance of the locality and that help maintain rural character. The infilling of these gaps will therefore not be permitted except where it comprises the development of a small gap within an otherwise substantial and continuously built up frontage.”

[55] Paras 4.5.0 and 4.5.1 further state that:

“There will also be some circumstances where it may not be considered appropriate under the policy to fill these gap sites as they are judged to offer an important visual break in the developed appearance of the local area.

As a general rule of thumb, gap sites within a continuous built up frontage exceeding the local average plot width may be considered to constitute an important visual break. Sites may also be considered to constitute an important visual break depending on local circumstances. For example, if the gap frames a viewpoint or provides an important setting for the amenity and character of the established dwellings.”

[56] As these paragraphs suggest visual gaps in rural areas are the very thing that collectively maintain the rural character of the countryside and distinguish it from the uniformly developed character of urban streetscapes. Para 5.34 categorically states that “the infilling of these gaps … will not be permitted” unless they come within the exception. The gaps referred to in these policies are inherently valuable because they maintain the rural appearance of the countryside. They can only be infilled if the conditions underpinning the exception are clearly established.

[57] The principal purpose of the reference to visual breaks within the additional guidance documents is to put a further break on grants of permission to develop small gap sites. What the guidance intends to make clear is that, even if the qualifying conditions are found to exist such that it can be rationally said that a small gap in a SCBUF is present, even then it does not automatically follow that an exception to the general prohibition on new ribbon development will be allowed. Before it is granted the decision maker must further assess whether there is a good planning reason for not granting permission, for example because the particular small gap site under consideration has a valuable characteristic which should be preserved such as framing a view or providing an important visual break.

[58] The thrust of the planning guidance in this area is to refuse infilling of gaps subject to the very limited cases where characteristic rural openness has already been destroyed because a pre-existing area of SCBUF has been identified. Even where the SCBUF is shown to be present, if the gap adds in some measure to the rural character of the area permission may be refused.

[59] The determination of whether a site offers a visual break of such significance is a matter of assessment for the decision-maker. This decision should be made with full understanding of the fundamentally prohibitive nature of the applicable policy and following due inquiry.

[60] As the judge noted, it is a matter of common sense that the larger the site, the more likely it is to offer an important visual break. In the present case by treating the manège gap as if it was a developed site with frontage the decision maker artificially extended the frontage measurement for No.12. On paper this had the effect of maximising the area of the road that could be treated as ‘continuously built up.’ However, this did not correspond with the visual impression of the area because visually the manège feature remained a gap. Treating it as part of a built-up frontage as the officer’s report did, only served to obscure the actual pattern of development on the ground. Treating the undeveloped manège gap as part of a built up frontage of No. 12 is unsustainable in the context of the governing planning policy.

[61] The question arises whether the very strong policy steer against ribbon development has been properly displaced by a fully informed decision of the Council in this case. Given the misleading impression created by the planning officer’s report and the fact that the councillors decided not to view the site themselves (even though this was not a legal error on their part) we are not satisfied that they were properly equipped to take the decision they took.

[62] The importance of the policies in play and the nature of the issues to be addressed must be to the forefront. The judgment required of decision-makers will almost certainly be vitiated if it is not exercised within the policy constraints and following due inquiry. Given the constraints inherent within the policy and the environmental importance of the rationale underpinning these restraints, fully informed scrutiny of any such proposal is essential.

Policy NH5 - the removal of the hedgerow

[63] The appellant also contended that the Council had not assessed whether development of the gap site in this case “meets other policy and environmental requirements” as required by Policy CTY8. In particular, he submitted that the environmental impact of removal of hedgerow was not investigated at all.

[64] The appellant is concerned that a significant portion of hawthorn hedge will be removed which would have an abundance of berries in the autumn which are eaten by both mammals and birds. Such removal would have an adverse impact on the food source available to wildlife. In addition to providing habitats for all kinds of wildflowers, bees, birds and small mammals, he has drawn attention to the fact that hedges are also critical wildlife corridors offering safe transit for wildlife (since open fields often offer no protection to animals moving from place to place).

[65] The judge noted that the appellant had provided photographs of the significant hedgerow along the front of the application site, some of which will be removed to provide access if the development proceeds. In advance of the judicial review hearing before the trial judge, the hedgerow was significantly cut back; but an established hedge nonetheless remains along the frontage to the Glassdrumman Road at the site.

[66] The appellant further contended that (i) the site plan and site layout plan are of insufficient quality to make it obvious how much hedgerow is to be removed when the permission is built out; (ii) the impact of creating necessary sightlines to facilitate access to the proposed dwellings will be to remove a very long section of hedgerow. The judge noted that in his second affidavit the appellant exhibited the Department for Infrastructure roads consultation response and, looking at the required visibility splays, estimates that around 50 metres of hedgerow will be required to be removed. The appellant contended that this loss was not adequately addressed by the Council’s Planning Committee, and that it cannot now be addressed adequately at the reserved matters stage.

[67] The appellant relied on supplementary guidance issued by the Department of the Environment in April 2015 entitled, ‘Hedgerows: Advice for Planning Officers and Applicants Seeking Planning Permission for Land Which May Impact on Hedgerows.’ Updated guidance, in materially similar terms, was issued by the Department for Agriculture, the Environment and Rural Affairs (DAERA) in April 2017 (“the DAERA hedgerow guidance”). This guidance emphasises that all hedgerows are a priority habitat due to their significant biodiversity value, which relates not only to the specific plant species within the hedgerow but to their wider value for foraging, providing shelter, and corridors for movement of large numbers of species. It emphasises the value of hedgerows. It references Policy NH5 of PPS2 and notes that: “the degree of impact depends on the net loss involved, the proportion of connectivity lost and the species richness and structure of the hedges that are lost or fragmented. There may also be protected, and priority species impacts that also have to be considered.”

[68] In response the respondent submitted that Policy CTY1 of PPS21 lists a range of types of development which are considered to be acceptable in principle in the countryside (including infill development in accordance with Policy CTY8). It is said that it is inevitable that there will be some loss of hedgerows as a result of such development, and it asserts that this is not generally likely to result in an unacceptable adverse impact on known priority habitats. The respondent also pointed to the fact that the removal of hedgerows does not itself require the grant of planning permission, such that the hedgerows in question in this case could perfectly lawfully have been removed by the planning applicant in advance of submitting a planning application.

[69] A landowner is quite entitled, without having to seek planning permission, to cut down a hedge on their land. However, as the judge correctly noted, that is to miss the point: “there is no reason to suppose that the landowners in this case were likely to remove significant portions of hedgerow unless and until they were granted planning permission. It is the building of the dwellings permitted by the impugned permission which is likely to be the catalyst for significant hedgerow removal.” As the judge further noted Policy NH5 and the DAERA hedgerow guidance proceed on the common sense basis that hedgerow removal should be taken into account in considering planning applications because - notwithstanding that it might be permissible to remove hedges without planning permission - the grant of planning permission, in the knowledge that the proposed development will require hedgerow removal, renders such removal much more likely.

[70] The respondent made the point that this issue was before the Committee and necessarily considered by them in the course of their consideration of the application. However, this begs the question ‘what could the councillors consider when they did not have a report on the level of loss and its impact. The issue of hedgerow removal was expressly referenced in the officers’ report in this case but only when summarising the objections received. It noted the objection that development “would block off a wildlife corridor” between Nos. 2 and 10 Glassdrumman Road and that the hedgerow to be removed for visibility splays “provides shelter for wildlife.” In addition, the issue was raised by the appellant before the Planning Committee (referenced in the minutes of its meeting of 16 December 2020 specifically noting the issue of the existing hedgerow being a wildlife habitat as one of the issues raised) and in the notice party’s written statement of 26 March 2021. It was also raised by the other objector, Mr Wilson, at that time.

[71] The judge said that the proposed site layout plan which formed part of the PowerPoint presentation to councillors did not provide a huge amount of detail but was sufficient to show an indicative sightline at the entrance to the new dwellings; further, it would have been obvious to the councillors involved that access from the road would be required; and they would be well aware that sightlines would be necessary (particularly in circumstances where some of the objectors raised road safety issues and an objection that the ‘double entrance’ to serve both proposed dwellings was too large). He observed that “it could not have been lost on them that hedgerow removal would be required to facilitate access to the site, which is why objectors were raising the issue. The Council accordingly granted permission in this case with its eyes open as to concerns in relation to hedgerow removal.”

[72] Are ‘open eyes’ enough? Is it enough for councillors to know that there is an issue in play, or must they have the data to make a proper assessment of the environmental impact of that issue? Policy NH5 provides that planning permission will only be granted for a development proposal which is not likely to result in unacceptable adverse impact on, or damage to known, priority habitats, species or other features of natural heritage importance. That being so it seems to us that it is vital that the decision‑makers have the necessary data to make the determination as to whether or not a particular proposal is likely to result in such unacceptable adverse impact.

[73] Indeed, even where a development proposal is likely to result in an unacceptable impact on such habitats, species or features, it may still be permitted in compliance with the policy if the decision-maker considers that the benefits of the proposed development outweigh the value of the habitat, species or feature (with appropriate mitigation and/or compensatory measures being required). In the present case no such assessment appears to have been made that any such potential benefits existed.

[74] The DAERA hedgerow guidance makes clear that all hedgerows meeting the definition in that advice are a priority habitat. Notwithstanding this guidance the judge held that it was open to the Council to conclude that the proposal in this case was not likely to result in unacceptable adverse impact on or damage to that habitat. The judge held that he had not been persuaded that the Council was ‘insufficiently informed’ of the likely net loss of hedgerows which would be involved in the proposal. Further, he said there was nothing in this case to indicate that an extended habitat survey was required. This was not a hedgerow with large trees; or where there was evidence of it being species rich; and it did not form a town boundary. Accordingly, he said that it was not a case where a survey of protected and priority species was necessary under the DAERA guidance. That guidance sets out a number of principles to be applied, which contain a significant degree of discretion (such as to “replace ‘like for like’ when replanting”, “retain connectivity where possible”, “integrate hedgerows into the development …”, etc). He also pointed out that the respondent relied on the fact that planning permissions for development in the countryside will generally contain conditions relating to landscaping matters; and, in this case, conditions 3 and 6 of the impugned permission, inter alia, reserve details including the means of access and landscaping to be approved at the reserved matters stage and preclude development from commencing until a landscaping plan has been submitted, which might properly include mitigating measures.

[75] On this aspect of the case the judge held that the appellant had failed to make out his case that this issue was not properly addressed by the Council. The judge said that it was a matter for the Council as to how deeply it enquired into that matter, and he was not satisfied that the Council left this issue out of account; nor that its conclusion (that the loss of hedgerow which was necessarily involved in the grant of this outline application was acceptable) was irrational.

[76] However there must be a qualitative aspect to their enquiry. We consider that the councillors cannot properly reach a conclusion on a matter of such environmental significance without basic data on the level of loss involved and on the species upon which these losses fall. Without this data there can be no effective enquiry. It is not sufficient for the Council to be ‘aware that an issue is in play’. Policy NH5 provides that planning permission will only be granted for a development proposal which is not likely to result in unacceptable adverse impact on, or damage to known, priority habitats, species or other features of natural heritage importance. Accordingly, this is a matter which has to be determined before the issue of permission is decided. To decide the issue the decision-maker must have the necessary data to make that decision. In our view, it is plain that they did not, and that the planning permission ought therefore not to have been granted.

[77] It is surprising that the planning officers did not draw to the councillors’ attention Policy NH5 of PPS2. The judge did observe that it would have been helpful if the Council’s planning officers had specifically directed councillors’ attention to the Policy. He also noted that it would have been helpful for some further photographs of the hedgerow to have been provided.

[78] The judge noted that the appellant is concerned about the cumulative loss of hedgerow, as well as cumulative development in the countryside more generally. In his grounding affidavit he states that there are over 2,000 one-off houses approved for development in the countryside in Northern Ireland every year. He has drawn this from planning statistics released by the Department. He contends that a significant proportion of these permissions relate to ‘infill’ housing. This results in a huge amount of investment in building in the countryside, rather than focussing such investment on urban regeneration. Even if development of the average rural house resulted only in removal of 20m of hedgerow, 2,000 rural houses per year would result in the annual removal of some 40km of hedgerow. The judge acknowledged this is a well-made point agreeing that “although each application coming before a planning authority must be addressed on its own merits, planning policy in relation to countryside development is generally in restrictive terms because each new development, whilst of limited effect on its own, adds to the overall impact of development in the countryside. Policies which require decision‑makers to carefully consider [environmental] issues such as hedgerow removal … should therefore be taken seriously.” The judge concluded that the issue was considered in substance by the Council in this case, largely through the emphasis placed on the point by objectors; but planning authorities should be alive to this issue even where it is not raised by objectors.

[79] We consider that the matter could not have been considered appropriately as the relevant policy was not drawn to the attention of the councillors and they were not provided with the basic data needed to conduct the balancing exercise required by it. These environmental issues are of great significance and require anxious scrutiny by the decision-makers. It is clear to us that these decision makers did not have the necessary data to determine this question properly.

Absence of a site visit

[80] The appellant contended that many of the matters raised by him are issues that should be considered after having visited the site and looked carefully at the local context, the general area, and the proposed site in particular. He submitted that these matters cannot be assessed by way of desktop analysis.

[81] The judge noted that the appellant “describes himself as having pleaded for the Planning Committee to visit the site to gather the visual information necessary for an objective decision to be made.” This suggestion was rejected by vote of the Committee. The appellant had also submitted a range of photographs but contended that these “still do not do the rural character and agricultural nature of this site justice”; and that this can only be properly appreciated by physical attendance at the site.

[82] It is an established feature of planning law that the decision-maker (i) must ask itself the right question and (ii) must also take reasonable steps to acquaint itself with the relevant information to enable it to answer the question correctly. This is often referred to as ‘the Tameside principle’) (see De Smith’s Judicial Review, 9th Ed, at paragraphs 6-040-6-042 and Dover District Council v CPRE Kent [2017] UKSC 79 at para [30]).

[83] The judge noted the respondent’s evidence that the councillors on the Planning Committee had viewed a presentation given by the planning officials, which included a PowerPoint presentation that contained various maps, plans and photographs. They also had presentations from the parties during the meeting and the opportunity to raise any questions or queries that they wished.

[84] The respondent’s Planning Committee operating protocol, which deals with the issue of site visits, states:

“[71] Site visits may be arranged subject to Committee agreement. They should normally only be arranged when the impact of the proposed development is difficult to visualise from the plans and other available material and the expected benefit outweighs the delay and additional costs that will be incurred.”

[85] At the meeting on 16 December 2020, having heard representations, the chairman asked for a proposal and two councillors proposed that the Planning Committee should undertake a site visit. That proposal was put to the Committee and declared lost in a vote of eight votes to two. The appellant again raised the issue at the Planning Committee meeting of 8 April 2021. Notwithstanding the points made by him on that occasion, the Committee still voted against such a site visit.

[86] At para [43](g) of Girvan J’s summary of the relevant principles in this area in Re Bow Street Mall and Others’ Application (supra) he held:

“If a planning decision-maker makes no inquiries its decision may in certain circumstances be illegal on the grounds of irrationality if it is made in the absence of information without which no reasonable planning authority would have granted permission (per Kerr LJ in R v Westminster Council, ex parte Monahan [1990] 1 QB 87 at 118b-d). The question for the court is whether the decision‑maker asked himself the right question and took reasonable steps to acquaint himself with the relevant information to enable him to answer it correctly.” (per Lord Diplock in Tameside)

[87] Scoffield J recognises the “significant benefits” in contentious planning applications of councillors themselves visiting a site: that the application of Policy CTY8 does involve decision-makers engaging with a number of concepts which entail the exercise of planning judgment; that the policy is fundamentally concerned with rural character, which is likely “to be best assessed” by a visit to the locus and consideration of the site from critical viewpoints; that in terms of assessing whether infill development in a gap site will result in the loss of an important visual break, such that it goes beyond the impact on rural character ‘priced into’ the policy exception, a site visit may well of “considerable assistance.” He also recognised that such visits take time and can result in delay and cost, which is why planning authorities have leeway in assessing whether they are necessary. He did not consider that the failure to conduct a site visit was a legal error.

[88] We endorse all that was said in the court below in relation to the value of site visits by the decision makers themselves, especially in difficult cases such as the present one. However, we cannot say that the decision maker, having considered the issue and voted upon it twice, can be found to have acted unlawfully in failing to visit the site.

Standing

[89] In granting leave to apply for judicial review, Scoffield J considered that the appellant at least arguably had sufficient interest in the matter to have standing for the purposes of section 18 of the Judicature (Northern Ireland) Act 1978 and RCJ Order 53, rule 3(5). Submissions on behalf of the interested party (Mr Carlin) accepted this to be the case in light of the fact that the appellant had been an objector in the course of the planning application process.

[90] However, the respondent continued to contend before Scoffield J that Mr Duff does not have a sufficient interest in the matter to which the application relates. Notwithstanding the appellant’s participation in the process before the Council’s Planning Committee, the Council contends that he is not directly affected by the outcome of the decision. On that basis it is submitted that he has insufficient standing to be granted any intrusive relief. The respondent relied, in support of this submission, on Walton v Scottish Ministers [2012] UKSC 44.

[91] The judge noted that the appellant has described himself as an environmental campaigner or protector of the environment. In recent times he has become a regular and frequent litigant before the court in cases which seek to raise issues about the interpretation and application of planning policy, usually in relation to policies within PPS21. He has made the point that, in his view, the Department has abandoned its role in maintaining the integrity of the planning system and that he feels that, in those circumstances, he is filling a necessary void as the only person willing to do so.

[92] The judge stated that, in fairness to the appellant, he has enjoyed some success in at least some of the cases which he has brought or supported. He addressed his position, in relation to the question of standing, in detail in the case of Re Duff’s Application (East Road, Drumsurn). He held that, for the reasons identified in that case, he considered that the appellant does have standing to bring the present application:

“Albeit he has no personal interest in the outcome (over and above his general concern for the environment), he was heavily involved in the planning process as an objector, including by way of written representation and appearance, having been granted speaking rights, at two meetings of the Council’s Planning Committee.”

[93] The judge went on to observe that the respondent’s point was a more nuanced one, namely that a different or separate analysis of the appellant’s interest was appropriate for the purposes of the grant of relief, even if he had sufficient interest to litigate the issues in these proceedings in the first instance. In light of the conclusions he had reached on the substance of the challenge, he held that this issue did not need to be addressed in his judgment.

[94] We are conscious that the appellant does not live in the affected area, nor does he have a direct interest in the site, although we do accept that he like other citizens is directly affected by issues such as biodiversity loss and environmental management. However, he did object to this planning application, and he has exposed significant matters in this case in relation to rural planning policy which exhausts the argument that he says arises in many other cases. Ultimately, his intervention also highlights the fact that planning permission was unlawfully granted. Therefore, the appellant as the only applicant is entitled in these circumstances to relief. We consider that the appropriate relief to remedy this unlawfulness is an order quashing the planning permission.

Conclusion

[95] This planning development application was presented to and decided by the Council on the basis that it came within the infill ‘small gap’ housing exception within Policy CTY 8. We have concluded for the reasons set out at paragraphs [28]‑[48] that the Council’s decision that this was a small gap site cannot stand.

[96] The primary focus of Policy CTY8 is on avoiding ribbon development, save where one of the two exceptions is engaged. Since Policy CTY8 is referred to in Policy CTY1 of PPS21 as being one of those policies pursuant to which development may in principle be acceptable in the countryside, there may be a temptation to view it primarily as a permissive policy. However, unlike the other policies, CTY8 does not begin by setting out that planning permission “will be granted” for a certain type of development. On the contrary, CTY8 begins by explaining that planning permission “will be refused” where it results in or adds to ribbon development. This is an inherently restrictive policy such that, unless the exception is made out, planning permission must be refused.

[97] The trial judge properly accepted that the exceptions should be narrowly construed bearing in mind the policy aim behind Policy CTY8 and PPS21 more generally. He further agreed that the exceptions provided for infill development are designed to allow for further development where the damage has already been done by the prior development of a ‘substantial and continuously built up frontage.’

[98] The trial judge did not consider the Council’s view that the houses on the Glassdrumman Road formed an “otherwise substantial and continuously built up frontage” to be Wednesbury irrational. He reached this conclusion with “some reticence” because of his acknowledgment that there was force in the appellant’s argument that the Council’s assessment has been ‘skewed’ to some degree by treating the ménage gap as part of the curtilage and frontage of No. 12. By doing so, the average plot size of the ribbon was “significantly increased.” The result of this is that No. 12 is then viewed as having greater frontage onto Glassdrumman Road than would otherwise be the case and the continuity of the frontage is maintained rather than being broken by the manège gap.

[99] In fact, “a large portion of [the frontage width of No. 12] is occupied by a manège [gap]” [see planners report]. This large portion of undeveloped land was a gap. We consider that treating this substantial visual gap, as part of the frontage of No. 12, is not rational having regard to the facts on the ground and the strictures and objectives of the policy. As we said earlier, where the infill exception is being relied upon a key question is whether there is a substantial and continuously built up frontage. That question must be addressed in light of the purpose of the policy and its inherently restrictive nature, and, of course, with proper regard for the physical features of the area in question. This concept of “otherwise substantial and continuously built up frontage” should be interpreted and applied strictly, rather than generously.

Importance of maintaining visual breaks

[100] For the reasons given at paragraphs [54]-[62] we have concluded that given the misleading impression created by the planning officer’s report and the fact that the councillors decided not to view the site themselves (even though this was not a legal error on their part) we are not satisfied that they were properly equipped to take the decision they took.

Priority habitats - Hedgerows

[102] We consider that the matter could not have been considered appropriately as the relevant policy was not drawn to the attention of the councillors and they were not provided with the basic data needed to conduct the balancing exercise required by it. These environmental issues are of great significance and require anxious scrutiny by the decision-makers. It is clear to us that these decision makers did not have the necessary data to determine this question properly (see paras [14]-[15] and [63]-[79])

Absence of site visit

[103] We endorse all that was said in the court below in relation to the value of site visits by the decision makers themselves, especially in difficult cases such as the present one. However, we cannot say that the decision maker, having considered the issue and voted upon it twice, can be found to have acted unlawfully in failing to visit the site (see [80]-[88]).

Standing

[104] For the reasons given at paragraphs [89]-[94] we agree that the appellant has standing in these proceedings.

Overall Conclusion

[105] In light of the foregoing we hold that the decision maker has not acted compliantly with its own policies which are designed to protect rural integrity and priority habitats and so the decision cannot stand.

[106] The decision will be quashed.

ANNEX 1