Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

Court of Appeal in Northern Ireland Decisions

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> Court of Appeal in Northern Ireland Decisions >> F v M (Hague Convention: Grave Risk) (Rev1) [2024] NICA 38 (15 May 2024)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/nie/cases/NICA/2024/38.html

Cite as: [2024] NICA 38

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

|

Neutral Citation No: [2024] NICA 38

Judgment: approved by the court for handing down (subject to editorial corrections)* |

Ref: KEE12505

ICOS No: 23/070334

Delivered: 15/05/2024 |

IN HIS MAJESTY’S COURT OF APPEAL IN NORTHERN IRELAND

___________

ON APPEAL FROM THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE IN

NORTHERN IRELAND

FAMILY DIVISION (OFFICE OF CARE AND PROTECTION)

IN THE MATTER OF THE CHILD ABDUCTION CUSTODY ACT 1985

Between:

F

Plaintiff/Respondent

and

M

Defendant/Appellant

(Hague Convention: Grave risk)

___________

Mr Magee KC with Mr E Cleland (instructed by Francis Hanna & Co Solicitors) for the Plaintiff/Respondent

Mr Toner KC with Ms L Brown (instructed by Millar McCall Wylie Solicitors) for the Defendant/Appellant

Ms Rice KC (instructed by the Official Solicitor) representing the interests of the children

___________

Before: Keegan LCJ, Treacy LJ and O’Hara J

___________

KEEGAN LCJ (delivering the judgment of the court)

This judgment has been anonymised as it involves three children. The cyphers given to the parents and children are not their initials. Nothing must be published which would identify the children or their parents.

Introduction

[1] The 1980 Hague Convention (“the Convention”) with which this case is concerned was adopted into our domestic legislation by the Child Abduction and Custody Act 1985. This was to accord proper recognition to the principle that a child’s interests must be protected in international disputes between estranged parents. In particular, the purpose of the Convention is to protect children “from the harmful effects of their wrongful removal or retention and to establish procedures to ensure their prompt return to the state of their habitual residence as well as to secure protection for rights of access.” The Convention is a forum treaty and provides for summary return to the courts of the habitual residence of the child. That is subject to the exceptions to return found within the Convention and the court’s discretion.

[2] The plaintiff, who is the respondent to this appeal, and father of the children seeks to maintain a return order made by McBride J (“the trial judge”) on 22 March 2024 in relation to his three children, namely the eldest child, who is now fifteen, the second child who is coming nine and a half and the third child who is seven.

[3] McBride J ordered that these three children be returned on or before 16 April 2024 to the United States of America.

[4] This appeal was mounted on four grounds, namely:

(i) The judge was wrong in determining that the children had been wrongfully retained in Northern Ireland.

(ii) That the judge should have refused to return the children on the basis of grave risk of physical, psychological harm or otherwise intolerable situation (the Article 13(b) defence).

(iii) In addition, the judge should have refused to return the children on the basis of the eldest child’s objection.

(iv) In any event, the judge should have stayed the return order for a period.

[5] The appellant is the mother of the children. She was unsuccessful in defending the return order. She is a naturalised US citizen. She married the plaintiff father who is a US national, on 8 May 2009. The parties separated on 8 May 2022. The father had studied for a time at Queens University Belfast. He also served in the US Marines from which he was discharged for ‘other’ (bad conduct).

[6] In these proceedings, the children have been separately represented by the Official Solicitor, Ms Kher. We have had the benefit of several very comprehensive reports from Ms Kher and heard from her counsel Ms Rice KC. As such we can say at the outset of this judgment that there was no merit in the argument faintly made by Mr Toner KC that the children should have separate representation. The children’s voices were well canvassed through the various reports in this case, and we see no prejudice occasioned to them and, indeed, no need for any additional representation in these proceedings or a further report.

[7] In opening his appeal, Mr Toner KC realistically abandoned the first ground of appeal in relation to wrongful retention. There is also no argument that at the relevant date of retention, namely 27 September 2023, that the children were habitually resident in the United States of America. The parties now agree that there was a wrongful retention in Northern Ireland by the mother from 28 September within Article 3 of the Hague Convention. Further, it is accepted that the father was or would have been exercising rights of custody at that time. The application has been brought within a year and there are no other impediments to it proceeding.

Factual background

[8] Since their separation the parties have been engaged with the District Court of Minnesota in the United States of America to try and settle arrangements. The first order of note is a joint petition to the American courts dated 14 June 2022 which provided that the mother and father would have shared care of all three children on alternate weeks with the rotations continuing in the summers. The shared care arrangement continued until the children were removed to Northern Ireland on 4 July 2023 by their mother. The circumstances of that removal are set out in the documentation, particularly, the Official Solicitor’s report which highlights the fact that the children did not expect this to be a permanent move and thought it was a road trip. The purported context of the move to Northern Ireland appears to have been that the mother’s father was ill at the time and that there was some agreement to a short term stay in Northern Ireland but not a longer-term permanent removal.

[9] This position is supported by the fact of the first relevant order which was made in the District Court in Wright County Minnesota on 27 September 2022. This order is termed an order for protection (“OFP”) pursuant to the Domestic Abuse Act. It is recorded that both plaintiff and defendant were in attendance when the court made various orders including that the respondent would not commit acts of domestic violence against the protected person, the mother. Also, the order includes, inter alia, the following term:

“The petitioner and respondent shall share joint physical and legal custody of the minor children; the petitioner should be allowed to reside in Northern Ireland with the children. The children should be allowed to attend school while residing in Northern Ireland. If the petitioner refuses to bring the children back to the United States, the respondent may bring a motion to modify custody solely on the basis of the petitioner refusing to return. This order for protection is effective until September 27, 2023.”

[10] On 22 March 2023, the plaintiff father issued legal proceedings for determination of permanent child custody and divorce. These proceedings form part of what has been termed a dissolution of marriage action and are pending in the Minnesota courts. The most recent documentation that we have received by way of summons and affidavit from the mother’s solicitor indicates that there is a notice of motion hearing in Minnesota on 17 May 2024 and that the case is listed for 25, 27 and 28 June. It is quite clear from the order of 26 December 2023 of the Minnesota court that the following was settled:

“(i) Issues regarding the children remain reserved pending the Hague’s release of jurisdiction.

(ii) An in-person court trial shall occur on Tuesday June 25, 2024 at 1pm, Thursday June 27, 2024 at 1pm and Friday June 28, 2024 at 1pm at the Wright County Justice Centre.”

[11] We also note that in relation to this there is a provision that all parties must appear in person. All witnesses must appear in person unless granted leave of the court. This is the order of the Honourable Suzanne Bolman, Judge of the District Court.

[12] That is the current position in relation to the family proceedings in Minnesota.

[13] As will be apparent from the above, on 4 July 2023 the mother travelled with the children to Northern Ireland via Iceland and the Republic of Ireland. On 27 July 2023, the plaintiff father applied ex parte to the US court for temporary change of custody, however, that was dismissed. On 1 November 2023, the plaintiff applied to modify the amended OFP made on 21 October 2023 which was dismissed on 22 October 2023. The plaintiff remains in the United States but did have direct contact with the children at Christmas 2023 in Northern Ireland and some indirect contact.

[14] As is often the case in these types of proceedings an expert report was obtained in the course of these proceedings to explain the import of the American proceedings. This has been useful and was an agreed document from a Ms Arnold which sets out the following propositions which we draw from para [28] of the trial judge’s decision:

“(a) The amended OFP dated 21 October 2022 was a valid temporary order which expired on 27 September 2023. She affirms that this interpretation is consistent also with the Minnesota court’s recent order denying the plaintiff’s motion to modify the order on the basis that the order expired on 27 September 2023 and, accordingly, there was no OFP to modify when he made his application in November 2023.

(b) The amended OFP permitted the mother to remove the children from the US during the period from the issue of the order on 21 October 2022 until the date of expiration on 27 September 2023. Accordingly, there was no wrongful removal in this case.

(c) The amended OFP was granted under the Domestic Abuse Act which explicitly only authorises temporary custody determinations. In contrast permanent custody determinations are made under the Marriage Dissolution Statute codified as Minnesota Statues Chapter 518. As such, this temporary order only permitted the defendant mother to temporarily remove the children outside the US to Northern Ireland and it was subject to her obligation to bring them back to the US.

(d) The mother was not lawfully permitted on foot of this order to permanently remove the children from the USA without taking further or additional steps/measures. The mother has not completed the necessary additional steps or measures to permanently remove the children from the US as no permanent custody order has been made by a Minnesota court to authorise permanent removal.

(e) Based upon F’s objections, the mother did not have the legal authority to retain the children in Northern Ireland beyond September 27, 2023, and, accordingly, the children’s retention in Northern Ireland was not lawful.

(f) The parties retain shared parental rights in the US and under the criminal law a parent who takes or retains or fails to return a minor child from or to a person after commencement of an action relating to child parenting time or custody but prior to the issuance of an order determining custody or parenting time rights, where the action manifests an intent substantially to deprive that parent of parental rights “may be guilty of a felony.”

This appeal

[15] The questions that arise for determination are threefold:

(i) Was the judge correct to reject the grave risk defence?

(ii) Was the judge correct to reject the child’s objection issue?

(iii) Was the judge correct to refuse a stay of the return order?

[16] We will deal with each of these issues in turn. In doing so we apply the appellate test whether the judge was wrong, which emanates from Re B [2013] UKSC 33 and Re H-W [2022] UKSC 17.

(i) Was the judge correct in her assessment of grave risk?

[17] Before we set out our conclusions on this first issue, we will briefly summarise the law in this area with the assistance of the guiding Supreme Court case of Re E (Children) (Abduction: Custody Appeal) [2011] UKSC 27. This is an authority which has prevailed in terms of the court’s approach to deciding whether a grave risk defence founded on domestic abuse is made out.

[18] Article 13(b) of the Convention provides that:

“The requested State is not bound to order the return of the child if the person, who opposes its return establishes that-

…

(b) there is a grave risk that his or her return would expose the child to physical or psychological harm or otherwise place the child in an intolerable situation.”

[19] The legal test in relation to grave risk that was set out in the arguments emanates from Re E from paras [32] to [36] as follows:

“32. First, it is clear that the burden of proof lies with the person, institution or other body which opposes the child's return. It is for them to produce evidence to substantiate one of the exceptions. There is nothing to indicate that the standard of proof is other than the ordinary balance of probabilities. But in evaluating the evidence the court will of course be mindful of the limitations involved in the summary nature of the Hague Convention process. It will rarely be appropriate to hear oral evidence of the allegations made under Article 13(b) and so neither those allegations nor their rebuttal are usually tested in cross-examination.

33. Second, the risk to the child must be grave. It is not enough, as it is in other contexts such as asylum, that the risk be real. It must have reached such a level of seriousness as to be characterised as grave. Although grave characterises the risk rather than the harm, there is in ordinary language a link between the two. Thus, a relatively low risk of death or really serious injury might properly be qualified as grave while a higher level of risk might be required for other less serious forms of harm.

34. Third, the words physical or psychological harm are not qualified. However, they do gain colour from the alternative or otherwise placed in an intolerable situation. As was said in Re D [2007] 1 AC 619 at para 52:

‘Intolerable is a strong word, but when applied to a child must mean a situation which this particular child in these particular circumstances should not be expected to tolerate.’

Those words were carefully considered and can be applied just as sensibly to physical or psychological harm as to any other situation. Every child has to put up with a certain amount of rough and tumble, discomfort and distress. It is part of growing up. But there are some things which it is not reasonable to expect a child to tolerate. Among these, of course, are physical or psychological abuse or neglect of the child herself. Among these also, we now understand, can be exposure to the harmful effects of seeing and hearing the physical or psychological abuse of her own parent. Mr Turner accepts that, if there is such a risk, the source of it is irrelevant, for example where a mother's subjective perception of events leads to a mental illness which could have intolerable consequences for the child.

35. Fourth, Article 13(b) is looking to the future: the situation as it would be if the child were to be returned forthwith to her home country. As has often been pointed out, this is not necessarily the same as being returned to the person, institution or other body who has requested her return, although of course it may be so if that person has the right so to demand. More importantly, the situation which the child will face on return depends crucially on the protective measures which can be put in place to secure that the child will not be called upon to face an intolerable situation when she gets home. Mr Turner accepts that if the risk is serious enough to fall within Article 13(b) the court is not only concerned with the child's immediate future, because the need for effective protection may persist.

36. There is obviously a tension between the inability of the court to resolve factual disputes between the parties and the risks that the child will face if the allegations are in fact true. Mr Turner submits that there is a sensible and pragmatic solution. Where allegations of domestic abuse are made, the court should first ask whether, if they are true, there would be a grave risk that the child would be exposed to physical or psychological harm or otherwise placed in an intolerable situation. If so, the court must then ask how the child can be protected against the risk. The appropriate protective measures and their efficacy will obviously vary from case to case and from country to country. This is where arrangements for international co-operation between liaison judges are so helpful. Without such protective measures, the court may have no option but to do the best it can to resolve the disputed issues. ”

[20] It is clear from this decision that a court must undertake a two-stage exercise. First, it must decide whether there is a grave risk of physical or psychological harm or otherwise intolerable situation on the facts; and secondly, whether protective measures in the country to which a child or children would be returned can offer adequate protection to the risk. In many cases a court when faced with this balancing exercise will have to consider evidence of allegations which are unproven between parties upon which to assess risk.

[21] In many cases the court also receives supplementary evidence relating to children and parents as to risk. The court deciding a Hague Convention application will also usually have the benefit of some evidence about protective measures in the State to which children should be returned.

[22] The trial judge has set out all the relevant principles which relate to the law in this area from para [40]-[46] of her judgment including a reference to Re E . We also derive assistance from the summation of law provided by Cobb J in RS v AM [2022] EWHC 311 at para [29]:

“29. The following principles emerge from Re E (Children) (Abduction: Custody Appeal) (the paragraph (§) numbers in [square brackets] below are from this judgment) and additional observations are collected from Re IG (Child Abduction: Habitual Residence: Article 13(b)) :

(i) Article 13(b) is, by its very terms, of restricted application: [§31]; the defence has a high threshold;

(ii) The focus must be on the child, and the risk to the child in the event of a return;

(iii) The burden of proof lies with the person, institution or other body which opposes the child's return. The standard of proof is the ordinary balance of probabilities, subject to the summary nature of the Hague Convention process: [§32];

(iv) The risk to the child must be "grave" and, although that characterises the risk rather than the harm, "there is in ordinary language a link between the two": [§33];

(v) "Intolerable" is a strong word, but when applied to a child must mean a situation which this particular child in these particular circumstances should not be expected to tolerate. Amongst these are physical or psychological abuse or neglect of the child: [§34];

(vi) Article 13(b) is looking to the future, namely the situation as it would be if the child were to be returned forthwith to his home country: [§35].

(vii) In a case where allegations of domestic abuse are made:

"… the court should first ask whether, if they are true , there would be a grave risk that the child would be exposed to physical or psychological harm or otherwise placed in an intolerable situation. If so, the court must then ask how the child can be protected against the risk. The appropriate protective measures and their efficacy will obviously vary from case to case and from country to country. This is where arrangements for international co ‑ operation between liaison Judges are so helpful." [§36] (Emphasis by italics added).

(viii) The court must examine in concrete terms the situation in which the child would be on a return. In analysing whether the allegations are of sufficient detail and substance to give rise to the grave risk, the judge will have to consider whether the evidence enables him or her confidently to discount the possibility that they do;

(ix) The situation which the child will face on return depends crucially on the protective measures which can be put in place to ensure that the child will not be called upon to face an intolerable situation when he or she gets home.”

[23] It goes without saying that issues of domestic abuse have received particular attention in Convention cases in recent times. That said we acknowledge that this defence has infrequently been made out. However, it must not be thought that satisfaction of the threshold is unachievable. A case from this jurisdiction where a child was not returned after a wrongful retention reported at [2012] NI Fam 5 illustrates the point. A return order was refused because of the risk of serious domestic abuse from a step ‑ father who it was found would be living in the home with the mother upon return. In refusing the return order the court said:

“A pervasive atmosphere of threats of physical violence and of repetitive, though minor abuse, gave rise to a grave risk of physical or psychological harm such that it would not be reasonable to expect the child to tolerate such an environment.”

[24] In this case the trial judge was not satisfied that evidence was sufficient to substantiate the grave risk defence in this case. However, as will become apparent we have heard fuller argument and received more evidence by agreement.

[25] By virtue of Article 16 of the Convention we are prohibited from making any welfare assessment. What we must do is assess risk and decide if a return should be ordered or refused based on exceptions within the Convention and whether the requesting parent and receiving State can provide adequate protective measures.

[26] The trial judge did consider the correct legal question which is whether grave risk is established. In doing so, her judgment sets out the history of domestic violence in this case and records an unusually objective touchstone which is that several court orders were made in the USA against the father in relation to domestic violence. There are, therefore, objective findings against him which is strong evidence of matters that have occurred and of risk.

[27] The domestic violence which has been validated by criminal convictions is on any reading significantly documented by the trial judge as follows:

“- On 25 July 2022, the mother applied for a harassment restraining order. This order was then dismissed on 30 August 2022 and the parties agreed a no contact civil order.

- On 27 September 2022 the mother obtained an inter partes order for protection ("OFP"). At this hearing the court made the following findings:

“Acts of domestic abuse have occurred, including the following: May 2022: Respondent yelling and screaming at petitioner, punched a hole in the bathroom wall and prevented petitioner from leaving the bathroom causing fear of bodily harm to petitioner. July 2022: Shouting and yelling at defendant causing fear of bodily harm to petitioner, petitioner called 911.”

- On 21 October 2022 the Amended OFP was made on consent of the parties.

- The defendant avers that the plaintiff has committed several breaches of the OFP for which he has been convicted and sentenced.

- The mother reported an incident of domestic abuse on 11 September 2021. She alleged that both parties had been drinking and a verbal argument ensued during which the plaintiff forced her out of the bed. He then opened a tabletop safe and removed a 9mm handgun and threatened her. When she called 911, he walked out of the bedroom, went downstairs. She then locked the bedroom door. The plaintiff reported a similar story but claimed that the handgun was in a downstairs safe and he denied that he had threatened the defendant with it.

- On 12 April 2022 the plaintiff pleaded to a reduced charge of misdemeanour domestic violence for the acts perpetrated against the defendant on 11 September 2021. On 20 April 2023 it appears from the court papers that this charge was then dismissed.

- On 7 March 2023, the plaintiff pleaded guilty to two violations of the protection order on 12 October 2022 and 5 August 2022. The breach on 5 August 2022 consisted of sending persistent text messages that did not pertain to parenting time or the care of the children. When the plaintiff was arrested in respect of this offence, whilst being escorted to the squad car he tensed up and ran towards a squad car and rammed his head into a window causing it to shatter. He created a dent below the window and broke the covering of the side emergency lights. As appears from the defendant's statements, the violation on 12 October 2022 consisted of sending large volumes of text messages which were in only in part about the divorce and which contained a vague threat that he was going to harm himself.

- The plaintiff was sentenced for these offences on 26 April 2023 and received a one-year supervised probation order with the following conditions:

“(i) He remain law abiding and have no same or similar violations;

(ii) He pay $285 within nine months.

(iii) He have no assaultative, aggressive or disorderly conduct;

(iv) He continue with individual counselling;

(v) He have no use or possession of firearms or dangerous weapons,

(vi) He complete domestic abuse batterers intervention programme,

(vii) He maintain contact with his probation agent and sign and abide by all probationary agreements.

(viii) On 26 April 2023 and 5 July 2023, the defendant made complaints that the plaintiff sent her numerous text messages about subjects unrelated to the care of the children and in which he made threats of suicide, in breach of the OFP. The plaintiff pleaded guilty to these two further breaches of the OFP.”

[28] In addition to the incidents which resulted in criminal convictions the mother also made other allegations of domestic violence against the father over a protracted period. As a result, it is unsurprising that the mother made the case in her affidavit evidence that the acts of domestic abuse committed by the father and the numerous breaches of the OFP constituted a course of conduct which is corrosive, and which has had a significant impact on her emotional well-being leading to her receiving medication from her GP and feeling in a state of heightened anxiety and feeling unsafe in her home.

[29] Further, as the trial judge referenced, the mother relied on a number of video clips which she took of her daughter having a face time conversation with her father on 8 March 2024. The mother submits that during this call the father threatened suicide (which the father disputes) and she submits that this is further evidence that he is now exercising emotional control over his daughter.

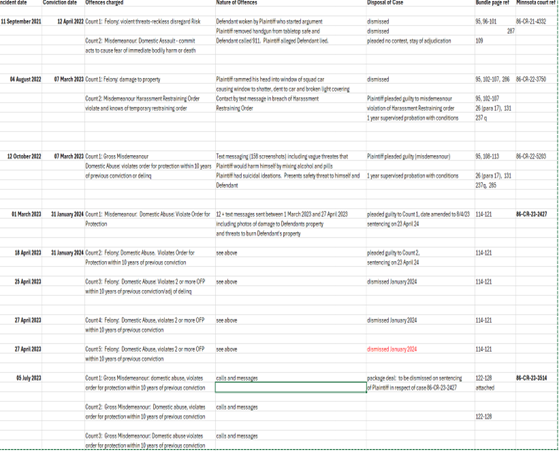

[30] We have had the additional benefit of a summary of the criminal convictions of the father which is highly relevant to our consideration. We set out this summary in the tabular format we received at Annex 1.

[31] It is readily apparent from the above that the father has been convicted of a number of serious offences involving domestic abuse. He has received a one-year supervised probation with conditions on 7 March 2023. We queried why a number of other counts appear to be dismissed and were told that these were aggregated into what was called a “package deal” and that all remaining charges would be dismissed on sentencing of the father in relation to the outstanding matters set out in the schedule above. That sentencing was to take place on 23 April 2024 and so we paused our judgment in the case until that came to pass.

[32] As it transpired, the sentencing was adjourned until 6 June 2024. Hence, we were not sure whether the package deal would be accepted or whether some other sentence could be imposed upon the father, including a sentence of imprisonment. We therefore asked the parties for further submission before the conclusion of the case.

[33] We had listed the case for judgment on 29 April 2024 but just prior counsel for the appellant asked us to reconvene on the basis that the father had misrepresented the position regarding the outstanding criminal proceedings. We asked for further submissions and documentation and postponed our judgment.

[34] As all parties accept the new information that we have received is highly relevant. It influenced the outcome in this case for the following reasons. First, contrary to what the father had instructed his counsel a five-year probation order was not inevitable. In fact, even prior to the first instance hearing he had signed a document dated 31 January 2024 agreeing to the “plea deal” which referred to a minimum of 30 days custody.

[35] The position of the State prosecutor is confirmed in a letter dated 1 May 2024 Significantly, this letter states, inter alia :

“… At a plea hearing on January 31, 2024, defendant entered a guilty plea and admitted to twice violating the OFP. The criminal matters are scheduled for sentencing on June 4, 2024. The plea agreement is as follows:

Defendant will be convicted of one gross misdemeanor count of violating the OFP and one felony count of violating the OFP. If defendant successfully completes felony probation, the felony charge will be reduced to a misdemeanor level offense at the conclusion of the probationary term which may last up to five years.

As part of the sentence, Defendant has completed a Pre ‑ Sentence Investigation (PSI). To complete a PSI, defendant meets with a probation agent for an interview. In this interview, the probation agent reviews defendant's social, economic, work, family, substance use/abuse, mental health, and criminal history. Based on the agent's findings, she makes recommendations to the court for probation requirements which may include various types of assessments, programming such as domestic violence programming, therapy, and/or counseling, among other things. At sentencing, the court will ultimately determine the fine amount, probation length, and other probationary terms based on the agent's recommendations and arguments of the parties.

Additionally, as part of this plea agreement, defendant may be sentenced to a maximum of 30 days of local incarceration in the Wright County Jail. The State of Minnesota intends to ask the sentencing judge to impose all 30 days of local incarceration as a consequence for defendant's criminal actions. If jail time is imposed, defendant may elect to serve the jail consequence over weekends (typically Friday evenings through Sunday evenings).

The State of Minnesota considered a number of factors when negotiating the aforementioned plea agreement. These considerations included, but are not limited to, the underlying nature of the offenses, your safety, the need for defendant to engage in domestic violence programming, the extent and nature of defendant's conduct throughout these legal proceedings, and the strengths and weaknesses of the criminal cases should they proceed to trial.

In these cases, the State has considerable safety concerns. More specifically, it appears to the State that defendant has engaged in a systemic pattern of domestic violence and harassment toward you both prior to these cases and throughout the criminal proceedings. As such, the State prioritized your safety by seeking probationary programming in exchange for a reduced consequence of a maximum of 30 days of local jail incarceration and securing criminal convictions.

Additionally, the State considered purported evidence - in the form of alleged text messages between defendant and you - presented by defendant in support of his case. The State reviewed this evidence in detail. While the State concluded the text messages presented by defendant are likely fabricated, these messages nevertheless pose a hurdle the State must overcome at trial.”

[36] Mr Magee KC frankly accepted that the father has not explained why he misrepresented the position regarding his criminal case to two courts in Northern Ireland. This lack of candour which we have uncovered is striking and unprecedented in the Hague cases we as a court have had experience of. We are also bound to say that the updating affidavit which the father filed dated 2 May 2024 on our direction provides no reassurance to us that the father is a man of truth at all.

[37] Of additional concern is the probation report which has been prepared for the criminal proceedings in Minnesota which we have received late in the case. This report is entitled “adult felony, domestic pre-sentence investigation” and is dated 22 April 2024. The report paints an extremely worrying picture as to the risk the father poses not just because of the offences he has committed, but because of his complete denial of the domestic violence found against him by the criminal courts of the USA.

[38] We set out some extracts from this report which we think speak for themselves under the following headings:

“Defendant’s statement

Defendant F wrote in his PSI packet the following: "Agreement made by Wright Co Judge But not in OFP order." The defendant believes there was a modification made in October 2022 saying the defendant and his ex-wife could communicate about anything. When asked about his plea agreement, he stated he believed it was fair. When asked what the most significant reasons are for the trouble he is in, he replied ‘Im fighting for custody of my kids and will never give up.’ He was asked what his opinion is of the law, police, courts and probation and he replied, "I Believe it's a good standard for criminals." He does not believe he has been treated fairly by the criminal justice system. During our interview, he made the following statements:

· Five years of probation is not fair

· I have never been violent

· All for punching a wall

· Wright County is out to get me

· I am a brilliant father

· She hit me with the car

· She called CPS on me 3 times

· She already kidnapped the kids but no impact on her”

Victim Impact

“It appears Victim M went back to her home country of Ireland taking the couple's children with her. This agent has not been in contact with M. However, Agent Anissa Moos completed a PSI on a prior offense and submitted the following victim impact statement with her report dated 4/17/23:

“To whom it may concern, I am sending this email as my victim impact statement and to try and explain the effect of what F did to me. As of March 15th, 2023, he told me that “he wasn't getting into the conversation of how he has a criminal record all because I wanted a divorce because I wanted to get out of our marriage so badly.” He has also stated that I have used the OPF as a strategy to get full custody of our children. He has never admitted to what he has done and has never taken accountability for his actions and the long term affects they've had on me and our children. He has refused to sign for the children's passports and has said he is just waiting for the OFP order to expire in September 2023 so I can't leave. He continually messages me about how I won't be leaving the country with the children and how he doesn't have any domestic violence charges against him since they dropped the violation of the OFP charges in exchange for a guilty plea for violation of the HRO. Before the OFP was put in place, there was a HRO that he breached and a mutual civil agreement that he also breached. He told me it's unlikely he will get jailtime and that if he does, his lawyer is going to ask that he serve it on house arrest, that the State are only currently looking at 30 days so far. That he may get fines of up to a $1000.00 and worst case is 90 days in jail. This all happened because of the night of September 11th, 2021, and I tried to support him and stand by him, asked for leniency from the prosecutor's office for him and then I realized that I was afraid of him. I was always watching and trying to predict the right thing to say or do, walking on eggshells because he would lose his temper so quickly and then I started to startle when he would come near me and back away when he approached me or raised his voice. I don't know if he was pointing the gun at me that night or not, he claims he didn't, but I do know that I thought he was going to shoot me and that's why I called 911. I did everything in my power to try and make sure he didn't get felony level charges that would ruin his life, but it made no difference in the end.

F spent months terrorizing me in our family home towards the end of our marriage. He would come to the house unannounced at 2am and 4am and refuse to leave because it was "his house" and he paid for it. He chased me up the stairs and trapped me in a bathroom with our two youngest children, wouldn't let me out and refused to leave, he was screaming at me in front of our children and punched a hole in the bathroom wall. He threatened to smash my laptop and demanded my phone because "he bought them" and he pulled me in a chair and a desk from across a room because he got upset when we were discussing the divorce proceedings and custody of the children. He had me backed into a corner in the kitchen one night and our then 7-year-old daughter came and stood in front of me because he was screaming at me and threatened to "kick the dog in the f*cking head" if he didn't stop barking. He was only barking because F was screaming and refusing to leave the house. On nights he would come to the house in the middle of the night, I locked myself in our children's room so he couldn't get to me, and he found the key and opened the door.

On another night, when I had hidden the key and taken the battery pack out of the door so the code wouldn't work, he used his key and then used a screwdriver from the garage to open the lock in the bedroom I was hiding in then followed me from that room across the hall to our bedroom. His favorite thing to say is he has never laid a hand on me and I'm just playing a game. Another night he rode his motorcycle up and down our street in front of the house revving the engine for 45 minutes from 3am-3:45am and when I messaged him and asked him to stop, he messaged back and said he could go where he wanted because it was a public street. He ended up waking our two younger children because our dogs were barking so much. He dumped our children and all their belongings on the curb to our house one night and said he was running away to Canada and never coming back, he then messaged me to say he had a bottle of Jack Daniels and a bottle of Percocet and was going to take them on his drive up to Canada and I wouldn't have to divorce him because I would be a widow.

I called in a wellness check on him and his vehicle was found in his then girlfriends house in Woodbury. He caused so much trauma to myself and to our children that we didn't spend the night at our home because he was acting so erratically that I didn't think we were going to be safe.

Since these events have happened, I struggle to sleep and when I do, I have nightmares about F every single night. Night was when he would do the most damage psychologically. I am constantly in a state of anxiety and hyper vigilance and get scared at the smallest of unexpected noises. I check my apartment door is locked hundreds of times a day, just in case he's been able to get past the security door downstairs, even though I know I locked it and there are cameras all over our apartment complex. I feel huge waves of panic and anxiety every time I must drop off the kids or pick them up from him. My heart stops every time I see a black Dodge Ram when I'm in town and I watch it until it disappears out of my sight, just in case it's him. I was taking an antidepressant for PMDD at a very low daily dose, and since this has happened, my dose has needed to be doubled because of my anxiety. I have panic attacks and flashbacks and worry every single time I get a message from him or see his name on the caller ID on my phone. If I refuse to engage with him over the phone or text message, I get told I'm not co-parenting and that I need to stop pretending I'm scared of him. That it’s not fair to punish our children and he doesn't understand why we can't celebrate special days like birthdays together. I have lost almost 50 lbs from the stress of the last year and I am terrified of him.

I don't really go out anymore, I rarely see my friends and when I do, I'm terrified I'll run into him. My body is constantly in fight or flight mode since all of this happened and I don't feel safe in my own home or in the town we live in. Half of my monthly income goes towards my rent, and I still don't feel safe here. Even reliving these events in this email has me shaking and my heart pounding. I'm a shell of the person I was before all of this happened and I don't feel safe anywhere anymore. I am always anxious, nervous, and scared now and have become very withdrawn. I have type 1diabetes and my management of it has also been affected by the stress and anxiety of the last year. I have had to take multiple PTO days from work because my anxiety and worry get in the way of my doing my job. I have no support system here as all my family are back in Ireland. I don't even have an emergency contact anymore as it used to be F. He takes no accountability for what he did, and that makes it worse because he doesn't see the damage, he has done to me and my overall health, both physical and mental. M.”

Domestic Abuse Assessment

Were alcohol or drugs involved? It does not appear that drugs or alcohol have been involved in defendant F’s offenses.

Were children present when abuse occurred? The current offense occurred over a text messaging conversation, so children were not present.

Level of violence/intimidation/injury of this incident: This agent was not able to speak to the victim in this matter; however, several documents were available to ascertain the following information: Victim M cited several concerning domestic abuse behaviors in her requests for no contact orders and her victim impact statement in the PSI from 2023. The victim stated the defendant has punched a hole in the wall, trapped her and their children in a bathroom, stalked her, pushed her up against a wall, loaded a firearm and pointed it at her, yelled at her while getting in her face, screamed at her in front of their children, threatened to commit suicide by drinking a bottle of Jack Daniels and taking a bottle of Percocet pills, and threatened to kick the dog. He has engaged in emotional abuse by calling the victim names, degrading her, gaslighting her by saying “stop pretending to be afraid of me.” In addition, he has stated as soon as probation is over she should be scared. The defendant engaged in minimize, deny, and blame, or "MOB " numerous times throughout our interview stating "I've never been violent", and "the alleged victim", as well as asserting Wright County is out to get him.

The defendant takes no accountability for his actions. Rather than talk about his own actions, he frequently cites all the things he believes the victim is doing wrong. She hit him with a car, she kidnapped their children, she called CPS on him three times, she made him lose his job, she has called the police on him over 60 times in the last two years. He sent paperwork to this agent's email on 4/08/24 which was supposed to be evidence that she has been violent and controls the children. He appears to be seeking validation without acknowledging his own behavior that brought him to this point.

Have police been called on other occasions? Yes, the defendant has three prior domestic-related offenses with this victim and law enforcement has been called on numerous occasions.

Past violence/pattern of abuse: The pattern of abuse appears to be only with this victim. It appears the violence has escalated over the course of the relationship and culminated in the defendant pointing a loaded gun at the victim. He has engaged in coercion and threats, intimidation, emotional abuse, isolation, MOB , male privilege, and economic abuse.

Most severe violence to this partner: The victim described in her victim impact statement from the 2023 PSI that the defendant proceeded to load his firearm then pointed it at her making her fear for her life.

Has there been prior counselling? Yes, Defendant F completed the Batterer's Intervention Program with Central MN Mental Health Center on 1/12/24. While the facilitator reported the defendant was able to demonstrate a clear understanding of the concepts discussed in the program, he is clearly not implementing this awareness as he continues to engage in MDB. When asked what he learned in BIP, he stated, "a lot" but could not verbalize one concept. The defendant also reported he is currently engaged in therapy.

If so, when/where? Completed BIP on 1/12/24.

Defendant's attitude: Defendant F’s attitude is deemed poor at this time. While it seems unreasonable for the victim to remove their children from the country and deprive them of their father, this does not negate the defendant's behavior in these incidences. He refers to the victim as "the alleged victim", minimizes his behavior by citing alleged behavior by the victim, and blames the system for being charged. He appears to have the attitude that the rules/laws do not apply to him. Despite recently completing BIP, he does not acknowledge violent behavior being anything other than physical abuse. This is highly concerning and suggests he will continue to be abusive toward the victim moving forward. This agent wonders if another round of BIP would be helpful. At the very least, it should be documented that he is discussing power and control tactics with his therapist.

Defendant's expectations for future relationship: The defendant wrote in his PSI questionnaire, "Never Marry again, get the custody of my kids". The defendant has no interest in a future relationship with the victim.

Is there a current OFP in effect? It is unclear if there is a protective order in place at this time.”

[39] In addition to the Pre-Sentence Investigation the defendant completed the Domestic Violence Inventory (DVI). As the report explains the DVI is an evidence based self-report risk instrument used to evaluate adults accused or convicted of domestic violence. The DVI evaluates risk on six independently scored scales: Truthfulness, Alcohol, Control, Drug, Violence and Stress Coping. We highlight some of the relevant scores of the father as follows:

“Truthfulness Scale: 77%

F’s Domestic Violence Inventory (DVI) Truthfulness Scale score is in the problem risk (70 to 89th percentile) range, which means all DVI scales (domains) are truth‑corrected to ensure their accuracy. This truth‑correction methodology is similar to that used in the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI), which is arguably the most widely used personality test in the United States. In summary, F’s Truthfulness Scale score is in the problem risk range and all scale scores are truth‑corrected for accuracy.

Violence Scale: 90%

F’s response pattern on the Violence Scale is in the severe problem or violent (90 to 100th percentile) range, which means F can be violent and dangerous. Carefully review F’s other Domestic Violence Inventory (DVI) scale (domain) scores as they could exacerbate F’s violent behavior. Other DVI scales include: Truthfulness, Alcohol, Drug, Control, and Stress Coping (Management) Abilities. As a general rule, the higher the scale score, above the 70th percentile, the more serious the problem. Recommendations: Consider intensive outpatient or inpatient treatment, his "Intention to harm" and his current court, probation or parole status as they would influence F’s level of care and supervision. Consideration might be given to individualized or (anger/violence management) group therapy.

[40] The overall assessment does not make for positive reading either illustrated by the following statements:

“Most concerning is Defendant F’s criminal thinking and attitude. As long as he is not taking ownership of his behavior, he will continue to have new offenses and violations. Even after completing the BIP program in January 2024, he continues to use MDB (minimize/deny/blame) as a way to excuse his behavior. Although it may be unreasonable for the victim to flee to Ireland with her children, one could also surmise that she fled to shield her children from the defendant's abusive behavior. The defendant appears to need further education regarding power and control tactics.

An LS/CMI assessment was completed along with this report. This tool assesses the defendant's risk to reoffend. Defendant F’s scored as a low risk to reoffend. Risk areas include criminal attitude, antisocial pattern and leisure/recreation. His strengths are criminal history, education/employment, peers, and alcohol/drug.”

[41] We acknowledge the fact that this report recommends probation. However, the father has expressly stated to this court via his counsel that he wishes to dispute this report and obtain his own expert evidence. This raises the distinct prospect that he may yet contest the charges. Nonetheless, we proceed on the basis which was accepted by all parties that a professional compiled this report for criminal proceedings and that it is evidence that we can take into account in our consideration.

[42] Such is the concern arising from the recent materials we have summarised above which were not before the trial judge that the Official Solicitor has changed her position and now maintains that a return of the children would present a grave risk of harm /intolerable situation and that the father could not be trusted to abide by any protective measures that the courts would put in place to mitigate the risks involved. The Official Solicitor raised the risk of imprisonment with no alternative care plan in place, the use of marijuana by the father and his fragile mental health and the father’s minimisation of domestic violence as particular concerns.

[43] There was unanimity amongst the parties that we should make our own assessment of the new material given the trajectory of this case rather than remit the matter to first instance. Given the time that has elapsed we accede to that course to provide a decision for all involved not least the children. Our assessment is as follows.

[44] As to the issue of domestic violence, the first question is whether a risk is established and then the severity of the risk. The mother’s case made upon the affidavit is to our mind compelling that she has suffered persistent domestic violence at the hands of the father. This violence has involved a concerning use of a firearm on one occasion. There has been some physical abuse, however, the psychological abuse is particularly strong in this case on the mother’s account of persistent harassment and gaslighting of her. There is objective evidence to validate the risk by virtue of the father’s convictions of domestic violence felonies and the domestic pre ‑ sentence investigation report. To our mind this objective evidence validates the mother’s other unproven allegations. If they are true (which is the test to be applied) a clear and grave risk is established. Hence, we are satisfied that the mother has established her case on the balance of probabilities not just by virtue of the criminal convictions but by the allegations of serious and persistent domestic abuse that she recounts in her affidavit evidence and that also appear in the recent pre-sentence investigation materials.

[45] From what we have read we consider the severity of the risk to be high given the repeat nature of the offending in violation of protective orders. The domestic violence, which has resulted in criminal convictions over a period of time involves not just erratic and violent behaviour on the part of the father including use of a firearm but persistent use of text and other messaging. These are matters of high concern and indicate future grave risk.

[46] The father’s case has always been that the mother has been violent towards him, and that the domestic violence alleged against him is exaggerated. We are not persuaded by either argument. The fact that the mother sent some emails to the prosecutor which referred to the father’s mental health issues does not undermine the seriousness of his offences. Nor is the domestic violence exaggerated. Rather the high-frequency messaging of the mother easily equates to coercive and controlling behaviour. We are far from satisfied that the father’s allegations against the mother are substantiated on the balance of probabilities.

[47] In addition, in terms of risk, we point out that courts in this jurisdiction have recognised the effect of domestic violence and coercive control upon the children caught up in such relationships; see Re H-N and others Children Domestic Abuse Finding of Fact Hearing [2021] EWCA Civ 448.

[48] One countervailing factor raised by Mr Magee is that there is no objective evidence from a medical report filed by the mother. We understand the point, however, it is not a trump card for the father as suggested. That is because we have sufficient evidence including a striking victim impact report which was not opened to the judge at first instance. This victim impact statement sets out vividly the negative effects of the persistent behaviour of the father on the mother. This mirrors the affidavit evidence, where at para [39] the mother also described the adverse effects upon her as follows:

“Generally, I could tell what mood he was in, and what was coming, and I tried to manage it and diffuse any situations. I was walking on egg shells. After the gun incident, I was very afraid of him, and I was highly anxious and hypervigilant. I suffered huge waves of anxiety and panic, I was fearful he could get past the locked doors and I struggled to sleep. I was taking a low dose antidepressant for PMDD and my doses had to be doubled due to my high levels of anxiety. I have had panic attacks and flashbacks and worried every time I got a message from him on the phone. I lost almost 50lbs in weight due to the stress. He failed to abide by the court orders in place and I didn’t feel safe. He taunted me saying he’d never hit me, but he failed to understand the devastating impact of his behaviours on me.”

[49] In addition, we find force in the argument that the father faces a difficulty convincing us that protective measures can mitigate the risks as he has breached court orders before. The higher the risk the stronger the protective measures need to be. The key question is whether the father would ever comply with an OFP or any other order of any court. We conclude that as the father has been the subject of protective orders in the USA and breached them persistently, there are in fact no orders which could protect against the high risk of domestic violence towards the mother that we have found exists in this case.

[50] That is not the end of this analysis because we must specifically consider the position of the children. The Official Solicitor has interviewed the children on a number of occasions about these matters. As might be expected this evidence is less clear. It is the eldest child who has referred to domestic violence within the family to some extent. There is also, some evidence that the children observed domestic violence as they witnessed the father punching a hole in the wall. In relation to this incident, the eldest child told the Official Solicitor that she saw her dad punch a wall once when her mum told her she was taking the eldest child and her siblings away from him. She went on to say that she had never seen her dad assault her mum. She did, however, say that when she was younger, she would have seen her mum hit her dad on the chest a couple of times and she thought this was just “messing.” None of the other children reported ever witnessing any domestic violence to the Official Solicitor.

[51] The trial judge was satisfied that the domestic violence perpetrated by the father upon the mother was not witnessed by the children and that the children could not have suffered an adverse impact of the domestic violence. In addition, the judge was influenced by the fact that all children spoke very warmly of their father to the Official Solicitor and did not raise any concerns regarding grave risk or an intolerable situation to her to the extent that the Official Solicitor’s initial recommendation which was that the grave risk exception was not established.

[52] We do not agree with the trial judge’s analysis on this issue. To our mind the trial judge underestimated the severity of the risk of domestic violence in this case particularly given the criminal convictions and the father’s attitude and has therefore fallen into error. We consider that she placed too much weight on the fact of shared care arrangements without enough thought to the effect of the father’s behaviour on the mother. We also think that the judge failed to fully appreciate that the risk also relates to the children.

[53] To our mind the grave risk is clearly established in this case by the father’s complete and utter denial of domestic violence and the lack of candour he has displayed in this court. Of lesser significance is the threat of imprisonment and the father’s own mental health although as the Official Solicitor highlights these factors cannot be ignored. This combination of factors amounts to a grave risk of psychological harm and/or intolerable situation for these children as the Official Solicitor contends for.

[54] Although not the most definitive evidence the video conversation between the father in March 2024 and his eldest daughter adds to our concerns in relation to his controlling behaviour.

[55] Having set out why we depart from the outcome reached by the trial judge we acknowledge several matters in fairness to the trial judge. First, the risk of domestic violence and coercive control was argued with much more force in this court, particularly by reference to the victim impact statement of the mother and the recent criminal investigation materials we received. Second, we have obtained more information including an official criminal record in relation to the father. Third, we now know more about the ongoing proceedings and that the father has not been candid about what was happening in those proceedings.

[56] We have also considered protective measures. In this regard we have drawn considerable assistance from the decision of Lady Wise in AD v SD [2023] CSIH 17, [2023] SLT 439. Whilst factually distinct the significant point we draw from that case which we think is highly relevant is that the non-adherence with protective measures in the host state of habitual residence is a factor whenever a court is deciding whether to make a return order ( AD v SD paras [37]-[40]). Lady Wise summed up the position thus,

“[40] We accept the submission by senior counsel for SD that there is little point in relying on a panoply of measures available in Illinois if there is no confidence that they will be complied with and where it may be too late after the event to protect SD and the children.”

This issue of potential noncompliance also arises in this case and is a potent factor in our consideration which we do not think the trial judge sufficiently reflected in her ruling.

[57] In summary, this father has a significant history of not obeying protective court orders. Hence, we conclude, not that the USA would not provide protective measures but that the father would not abide by them. Therefore, we do think there is a compelling argument that the father would not abide by protective measures against her and may continue to harass her by way of persistent text messages or other irrational behaviour.

[58] In addition, we apply the line of authority which has been adopted by all counsel that any protective measures must be in place prior to return see Re K (A Child) (Child Abduction) (Rev1) [2020] NIFam 9.

[59] One last consideration is that the mother has quite clearly before the lower court and in this appeal said that she is not returning to the USA no matter what happens. It could be said that thereby the effect of domestic violence is removed from the case. This argument has limited attraction for the simple reason that it fails to embrace the damaging psychological effects caused by a parent in denial such as this father. The associated risks are not theoretical within a family dynamic where the children want to have a relationship with both parents and have had to date.

[60] In addition, given the fact that the father has not been forthright with this court we could simply not be satisfied that he would abide by the undertakings previously proffered. Specifically, as he seems aggrieved by being prosecuted on the mother’s complaint we could not be satisfied as to his undertaking not to make or pursue any criminal complaint against the defendant mother and shall withdraw all complaints already made, if any, against the defendant mother arising out of the circumstances of the children’s removal from the USA to Northern Ireland. Put simply, we have no confidence in his ability to adhere to any of the undertakings he may provide given the way he has approached this case with a lack of candour and the misleading instructions he has given to his counsel.

[61] Accordingly, for the reasons we have given, the first ground of appeal succeeds, and we find the grave risk exception to be established on the evidence we have considered on the balance of probabilities.

(ii) Was the judge correct in refusing return on the basis of the elder child’s objections?

[62] This appeal ground was pursued much more tepidly by Mr Toner. He argued that the return order should be refused because the eldest child has a degree of maturity which it is appropriate to consider her views and she objects. There is no suggestion that the children should be separated so the argument goes that if she refuses all children should remain in Northern Ireland on this basis.

[63] The law in relation to this issue has been expertly set out by the trial judge as encapsulated in the seminal case of Re M (Republic of Ireland) (Child's Objections) (Joinder of Children as Parties to Appeal) [2015] EWCA Civ 26 which was endorsed by the Court of Appeal in Re F (Child's Objections) [2015] EWCA Civ 1022 . This area of law was helpfully summarised in Re Q and V (1980 Hague Convention and Inherent Jurisdiction Summary Return) [ 2019] EWHC 490 (Fam) as follows [at para 50]:

“(i) The gateway stage should be confined to a straightforward and fairly robust examination of whether the simple terms of the Convention are satisfied in that the child objects to being returned and has attained an age and degree of maturity at which it is appropriate to take account of his or her views.

(ii) Whether a child objects is a question of fact. The child's views have to amount to an objection before Article 13 will be satisfied. An objection in this context is to be contrasted with a preference or wish.

(iii) The objections of the child are not determinative of the outcome but rather give rise to a discretion. Once that discretion arises, the discretion is at large. The child's views are one factor to take into account at the discretion stage.

(iv) There is a relatively low threshold requirement in relation to the objections defence, the obligation on the court is to 'take account' of the child's views, nothing more.

(v) At the discretion stage there is no exhaustive list of factors to be considered. The court should have regard to welfare considerations, in so far as it is possible to take a view about them on the limited evidence available. The court must give weight to Convention considerations and at all times bear in mind that the Convention only works if, in general, children who have been wrongfully retained or removed from their country of habitual residence are returned, and returned promptly.

(vi) Once the discretion comes into play, the court may have to consider the nature and strength of the child's objections, the extent to which they are authentically the child's own or the product of the influence of the abducting parent, the extent to which they coincide or at odds with other considerations which are relevant to the child's welfare, as well as the general Convention considerations ( Re M [2007] 1 AC 619 ).

I also note that in some cases an objection to a return to one parent may be indistinguishable from a return to a country.”

[64] This court has had the assistance of two reports of Ms Kher, solicitor to the Official Solicitor, of 10 October 2023 and 15 March 2023 in relation to this. We have noted the extremely positive comments from each of the children about their father within both of the reports, with all three reporting to miss him and to enjoy spending time with him. Dealing with the eldest child wherein the objection is raised, she identifies within the first report that life was good in the USA. She reports the trauma of how she came to be in Northern Ireland which she says was not planned by her mother and she feels betrayed by her. She sought a return to the USA as did the other children in the first report.

[65] In the second report the child expresses no active opposition to a return to the USA, but she does refer to the fact that she would like to study at Queen’s University, and she is less vocal about a return. The height of the second report is that the child advised that she had ‘kind of’ changed her mind and now wanted to stay in Northern Ireland as she wants to go to college here. She said she had been feeling pressure from her parents, a point picked up by the Official Solicitor, who commented as follows:

“None of the children expressed a strong objection to returning to America, notwithstanding the equivocation of the eldest child in the second interview.”

[66] The judge decided as follows:

“Whilst the eldest child in the second interview stated a change in her position, I consider she was simply expressing a preference to remaining in this jurisdiction rather than expressing an objection to return to the USA and given the pressure she had been placed under by her mother since the date of the first report, I consider her recently expressed views may not represent her true wishes.”

[67] We are entirely in agreement with the judge’s analysis of this issue. The change of view, if it is a change of view, is not sufficient to meet the test of a clear and unequivocal objection to return freely made which represents the true views of this eldest child. She has been caught in the middle of a parental dispute and as the eldest child is most likely to be strongly affected by it. We can see nothing in the Official Solicitor’s reports or in other evidence that would militate against a return or satisfy the test of objection to returning to the USA.

[68] We dismiss this ground of appeal.

(iii) Stay of a return order

[69] The third ground of appeal evolved during the hearing. It is now overtaken by our conclusion on ground 1 but we will briefly set out our views for completeness’ sake as follows.

[70] The trial judge did at the end of her judgment deal with an application for stay of the order and rejected the application. She rightly records that Article 12 of the Convention mandates that the court shall make a return order when the provisions of the Hague Convention are met and none of the exceptions are made out. Notwithstanding this, a court can, in exceptional circumstances, suspend or stay a return order.

[71] BK v NK [2016] EWHC 2496 is the only authority that has been cited to us in this area. It is a decision of MacDonald J in relation to stay. However, it is in a very unusual circumstance, where the father was seeking return of the child to a country when he was no longer in the country to which the child was to be returned. Rather obviously, these circumstances eventually led to the grant of a stay of proceedings. This is the thin edge of the wedge which will rarely arise in cases of this nature. Self‑evidently, such stark facts do not arise here.

[72] However, it does appear to us that we have an inherent jurisdiction to provide for a stay in a variety of other circumstances. This argument evolved during the hearing from an application for a stay of a week to an agreed stay until the criminal court would conclude and then an application for a stay to allow the children to finish their education in Northern Ireland and return to the USA at the end of June should the court make a return order. The parties also filed additional submissions on this issue of stay following the postponement of the father’s sentencing which we have considered.

[73] Those submissions accept that there is an expectation that, absent a defence being established, a return order will not be stayed and exceptions to return have to be interpreted strictly: Campanelli v Russia (App No. 35474/20). This principle is also reflected in the clear terms of Article 12, which refers to a return ‘forthwith.’ Whilst case law reflects a residual power pursuant to the rubric of the Convention to give effect to short delays with respect to return, these have been focused on situations such as allowing time to (1) implement protective measures to smooth transition or (2) regularise the affairs of the parent to organise return: see, for example AO v LA [2023] 2 FLR 465 (3 week period allowed); R v K (Abduction: Return order) [2010] 1 FLR 1456.

[74] In relation to the issue of stay we were referred to In Re E (Abduction: Article 13B Deferred Return order) [2019] 2 FLR 615. Gwynneth Knowles J at paras 104 to 106 considers the case law in this area and the limited circumstances in which stay applications are considered. Also, In NT v LT (Return to Russia) [2020] EWHC 1903 (Fam), [2021] 1 FLR 773 Cobb J refused an application for a deferred order, opining as follows at para 106 (and endorsing the views of MacDonald J in BK v NK [2016] EWHC 2496 (Fam):

“I would be failing in my obligations under the Convention if I suspended or stayed the outcome in such a way as to thwart its purpose i.e. to “order the return of the child forthwith” (Article 12).”

[75] This case has unusual features which do not appear in any of the cases we have read. In addition, the timing of the original stay application was significant. We would have made the effective date for return dependent on the criminal proceedings completing in the manner put forth by the father (ie the probation order) and on the basis that protective measures would be put in place. Therefore, if we had found in favour of return the effective date would realistically not have been until mid to late June. Matters have moved on since then given our conclusion on grave risk explained above and so the issue of stay is a moot point.

Discretion

[76] Given our conclusion that there is a grave risk that return to Minnesota would expose the three children to a grave risk of physical or psychological harm or otherwise subject them to an intolerable situation there can be no question of us exercising our discretion to order return.

Conclusion

[77] Accordingly, we allow the appeal on ground one namely the grave risk of psychological harm or intolerable situation if a return of the children is ordered.

[78] In so finding we acknowledge that the Minnesota Court is currently seised of the family case and that it is listed for hearing in June. The emphasis should now be on settling welfare arrangement for these three children as soon as possible. We will hear from counsel as to any ancillary matters that arise.

ANNEX 1