Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

Supreme Court of Ireland Decisions

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> Supreme Court of Ireland Decisions >> University College Cork v Electricity Supply Board (Approved) [2020] IESC 38 (08 July 2020)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/ie/cases/IESC/2020/2020IESC38_0.html

Cite as: [2020] IESC 38

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

Summary

THE SUPREME COURT

[Record No. 70/18]

Clarke C.J.

MacMenamin J.

Dunne J.

Between/

University College Cork - National University of Ireland

Plaintiff/Appellant

and

The Electricity Supply Board

Defendant/Respondent

Joint judgment of Mr. Justice Clarke, Chief Justice, and Mr. Justice MacMenamin delivered the 13th July, 2020.

1. Introduction

1.1 Cork City suffered very severe flooding on 19 and 20 November 2009. A principal cause was that the River Lee broke its banks, thus subjecting many nearby properties to significant damage. Amongst those who suffered was the plaintiff/ appellant, University College Cork (“UCC”), where the campus was severely damaged.

1.2 UCC has claimed that the defendant/respondent, the Electricity Supply Board (“the ESB”), was negligent or guilty of nuisance in the way in which it handled its up-river dams at Inniscarra and Carrigadrohid, thus causing or contributing to at least a significant part of the flooding concerned. On that basis, UCC commenced these proceedings alleging negligence and nuisance against the ESB. The ESB denied that it was guilty of either negligence or nuisance, but pleaded, in addition, that if it were liable, UCC should be found guilty of contributory negligence and thus have its damages reduced.

1.3 In the High Court, UCC succeeded in part, in that the trial judge (Barrett J.), for the reasons set out in a written judgment dated 5 October 2017 (University College Cork - National University of Ireland v. Electricity Supply Board [2015] IEHC 598) concluded that the ESB were liable but also held UCC to be guilty of contributory negligence, which he measured at 40%.

1.4 Both sides appealed to the Court of Appeal. In a judgment of that Court delivered by Ryan P. (University College Cork – National University of Ireland v. Electricity Supply Board [2018] IECA 82), the appeal of the ESB in respect of the finding of liability made against it was allowed and thus the judgment of the High Court against the ESB and in UCC’s favour was set aside. The Court of Appeal went on to consider whether UCC could properly have been found guilty of contributory negligence, for there remained the possibility of an appeal to this Court in which the question of contributory negligence could again become relevant if this Court were to take a different view on the initial liability of the ESB. The Court of Appeal came to the view that UCC should not have been found guilty of contributory negligence.

1.5 Thereafter, both sides successfully sought leave to appeal to this Court in terms to which it will be necessary to turn. Thus, both the question of the primary liability of the ESB and the potential liability of UCC for contributory negligence are before this Court. However, in the course of case management, it was decided that the Court would initially consider the question of whether the ESB could properly be found to be liable. Clearly, so far as a court of final appeal is concerned, there is no need to go on to consider the question of contributory negligence in the event that there is no sustainable finding of primary liability in the first place. Thereafter, a hearing followed on the question of the liability of the ESB. The question of whether any contributory liability can be attached to UCC has been left over until that issue has been determined and, obviously, will not need to be determined in the event that no liability attaches to the ESB.

1.6 Put at its very simplest, therefore, the issue on this appeal is as to whether the High Court was correct to find that the ESB was liable in negligence and/or nuisance or whether the Court of Appeal was correct to find that it was not. However, behind the broad issue expressed in those simple terms, there are potentially a range of issues which can contribute to a final determination as to whether the ESB is liable.

1.7 In order to understand the issues in a little more detail, it is necessary to at least start with a brief overview of the facts.

2. The Facts - An Overview

(a) General Background

2.1 It is proposed to deal with detailed aspects of the facts relevant to the issues which arise on this appeal in the context of the specific issues as they arise. For present purposes, it is sufficient to give an outline of the background facts so as to place those legal issues within their general context.

2.2 The River Lee flows through Cork City, which was built on its floodplain. The city is susceptible to both fluvial and tidal flooding. In 1949, the Lee Hydroelectric Scheme (“the Lee Scheme”), for the generation of electricity by means of hydraulic power, was approved for construction by the Minister for Industry and Commerce, under the Electricity (Supply) (Amendment) Act 1945 (“the 1945 Act”). The scheme as approved was built between 1952 and 1957.

2.3 The Lee Scheme comprises of two dams (“the Lee Dams”), each impounding a reservoir of water. The power station, dam and reservoir at Inniscarra (“the Inniscarra Dam”) are located approximately 14km upstream of Cork City. Approximately 13km further upstream, there is a second power station, dam and reservoir located at Carrigadrohid (“the Carrigadrohid Dam”). The Lee Dams work together for the most part and outflow from the Carrigadrohid Dam is discharged directly into the Inniscarra Dam system. The Hydro Control Centre in Wicklow is responsible for the normal operation of the Lee Stations. However, management of water levels and flood management are dealt with from the control room at Inniscarra Power Station under the Hydrometric Officer’s instruction.

2.4 The operational rules of the Lee Scheme are contained in the Lee Regulations (“the Regulations”) which is an internal ESB document the first version of which was published in 1969. The Regulations have been subject to a number of subsequent revisions and, it should be noted, do not have statutory standing. The Regulations contemplate, amongst other things, the operation, management and control of the Lee Dams both in normal conditions and in flood events and also contain rules, procedures and guidelines to be applied in respect of the water levels of the reservoirs, the management of water discharges and flood management.

2.5 The Lee Dams are classed as “Category A” dams, meaning that a breach of such a dam would endanger the lives of a downstream community. Dam integrity requirements are therefore fundamental to the Lee Regulations.

2.6 The Lee Regulations outline three separate levels against which the water in the reservoirs can be measured. The first of these is the “Maximum Normal Operating Level”, referred to as “MaxNOL”, which is defined as meaning “the highest level allowable in the operation of the reservoir under normal operating conditions”. It can only be exceeded under special flood instructions. Once MaxNOL is reached, water must be discharged in accordance with the Lee Regulations, for to ordinarily allow reservoir storage above MaxNOL is considered an unacceptable risk to dam safety, as the danger exists of dam failure resulting from spilling of large quantities over the top of the barrier. The Target Top Operating Level (“TTOL”) for both Lee Dams are also prescribed in the Lee Regulations. This level is defined as the “top operating level which the station shall endeavour to maintain during non-flood conditions” and, while it varies during the year to accommodate seasonal weather conditions, it is always lower than MaxNOL. The “Minimum Normal Operating Level”, referred to as “MinNOL”, is the lowest level at which the normal operation of the plant is possible.

2.7 The Regulations prescribe how discharges are to be managed during floods, in order that the Lee Dams are capable of dealing safely with floods, by providing that specified amounts should be discharged at specified reservoir levels. In order to understand the appropriate procedures, it is necessary to start by saying a little about the concept of “spilling”. Essentially, all water entering into the system of either dam passes to the downstream side of the dam concerned either by passing through the turbines and thus generating electricity or by being “spilled”, that is permitted to pass through gates designed to allow for the release of water beyond that which passes through the turbines.

2.8 A “flood period” begins when, in the judgment of the Hydrometric Officer, conditions and all available information indicate that spilling may be necessary. During a flood period, the Regulations provide that “the top priority is the proper management of the flood to avoid any risk to dam safety”. General hydroelectric generation practice requires that dam integrity be ensured by following a mandatory discharge regime at specified levels. Discharges are generally made through the turbines, as part of normal station operations, although in advance of a potential flood, water may also be “spilled”.

2.9 Based on operational experience, a discharge of up to 150 m3/s from the Inniscarra Dam is considered by the ESB to be that which will remain “in-bank” (that is within the banks of the river) and thus flooding should not result. Discharges greater than 150 m3/s are likely to breach the river-channel capacity and cause flooding. For that reason, the Regulations require that discharge should not exceed peak in-flow. Thus, the assumption behind the Regulations is that it is permissible when required in the appropriate circumstances to discharge more water than is coming into the system but only where that discharge will be not more than 150 m3/s. In that context, it is worth noting that the normal flow through the turbines when they are operating to their full capacity is somewhere between 80-85 m3/s. Thus, it is possible to discharge an additional 65-70 m3/s without exceeding the 150 m3/s threshold. While it is undoubtedly the case that a discharge above the level of inflow has an effect downstream by increasing the flow of water, experience has shown that increasing the outflow in a way which does not exceed the 150 m3/s threshold is most unlikely to cause flooding as such.

(b) November 2009

2.10 The events of November 2009 are central to the issues before this Court. That month was a time of very wet and windy weather in Ireland. The storm in the area of Cork, and the resulting rainfall in the Lee catchment area leading up to and on 19 and 20 November, was the worst in the history of the Lee Dams. As the water levels rose in the Lee Dams, ESB controllers allowed the flow of the river through the system to increase by degrees, but ultimately very substantially, in accordance with the protocols for such situations. Ultimately discharge at more than 500 m3/s occurred until the storm abated and water levels fell. This resulted in severe flooding downstream, causing significant damage to the properties of UCC and others. It does not appear that the outflow through the system at critical times on November 19 and 20 exceeded the inflow. However, in simple terms, the principal contention put forward on behalf of UCC is that, in the days and weeks leading up to the critical events of that time, the ESB negligently left less scope or capacity in their reservoir system for water than should have been the case. On that basis, it is argued that at least the worst problems of the flooding could have been prevented or alleviated had the reservoir system been capable of absorbing a greater volume of water on the occasion in question.

2.11 On a separate question, the ESB operates an ‘opt-in’ warning scheme that notifies residents downstream of the Inniscarra Dam that discharges additional to normal turbine operation will occur. As the situation developed during 19 November 2009, the ESB activated its notification system by alerting people on its contact list that water discharges from Inniscarra were being increased in response to the increased in-flow and the risk of flooding. As the situation deteriorated, the warnings became more urgent and were broadcast widely in the region.

2.12 In due course, UCC sought to recover from the ESB the substantial cost of repairs and losses arising from the flooding of its campus buildings. In January 2012, UCC issued proceedings against the ESB claiming damages in, amongst other things, negligence and nuisance.

2.13 In the light of that overview, it is appropriate first to record the conclusions of fact reached by the High Court and to identify the legal basis on which the High Court considered that the ESB was liable.

3. The High Court Judgment

3.1 The hearing in the High Court lasted 104 days and resulted in the handing down of a written judgment of over 500 pages by the trial judge. The case made by UCC was that the ESB owed a duty of care to UCC and other downstream occupiers to avoid what was described as unnecessary flooding. Accordingly, it was said that the ESB should have anticipated the heavy inflow of water that the storm would bring and should have endeavoured to ensure that it had sufficient space in the reservoirs to accommodate the flood waters when they arrived. On that basis, it was said that a substantial part of the damage which UCC suffered would have been prevented.

3.2 The ESB acknowledged that it had a duty of care to downstream occupiers, but only in respect of the risk of dam failure and in respect of the risk of flooding caused by the discharge of water in greater quantities than that which entered the dam systems. ESB’s case was that its statutory function was to generate electricity and that, while it endeavoured to reduce flooding in a manner consistent with this primary obligation, it was not legally bound to do so. On that basis the ESB argued that it did not owe a duty of care to avoid unnecessary flooding. Further, the ESB maintained that the Lee Scheme did not add to the flooding but, in fact, reduced it.

3.3 The trial judge held that the ESB was liable in negligence and nuisance in regard both to flooding and warnings. In particular, it was concluded that the ESB should have kept water levels in its reservoirs lower at TTOL in order to create more storage space. In the course of the judgment, Barrett J. set out a chronology of events which took place between 16 and 20 of November 2009, setting out the details of the evidence provided in relation to the flood event which took place in Cork City on 19 and 20 November 2009. The trial judge also noted the decisions made in relation to the operation of the Lee Dams and the spilling of water therefrom in the days preceding the flood event. The trial judge also answered no less than 261 “Key Questions of Fact” which were submitted by the parties. While the relevant findings of the High Court will be considered in more detail shortly, it should be noted that a number of issues canvassed before that Court do not remain alive before this Court.

3.4 The ESB drew attention to the fact that the powers conferred on it by s. 34 of the 1945 Act, which allowed it to control, alter or affect the water levels of the Lee Dams, required it to exercise those powers “in such manner as the Board shall consider necessary for or incidental to the operation of those works”. On that basis the ESB contended that these powers were conferred only to assist in hydroelectric-generation and that, while flood alleviation is generally incidental to this pursuit, the obligation to alleviate flooding cannot be implied into the legislative scheme where it is inconsistent with the ESB’s statutory mandate to generate electricity. There is, of course, a distinction between a statutory power and a duty of care. In rejecting ESB’s argument, Barrett J. considered that it was undermined by a number of factors. Those were that the ESB had, in fact, performed a flood alleviation role for decades. The trial judge adverted to the provisions in the Regulations which were directed toward facilitating flood alleviation and allowing for advance discharges in order to create more storage for incoming floods and to reduce peak discharge. Barrett J. also laid weight on the fact that he considered that over the years the ESB had made public representations to the effect that public safety was its utmost priority. He held this voluntary assumption of responsibility was sufficient in itself to create a duty of care.

3.5 The trial judge also considered that there could “be no serious dispute” but that UCC had reasonably relied on this duty of care, derived from the assumption of responsibility, based on the ESB’s “various utterances to the world at large as regards flood attenuation over the years” and based on the inclusion of UCC on the opt-in warning list. Further, the High Court provided a number of reasons why it considered that the objectives of flood alleviation and the ESB’s statutory “mandate” of hydro-generation were compatible. The Court noted, amongst other things, evidence to the effect stated that these aims were not mutually incompatible and that the Lee Scheme was capable of fulfilling both functions and also that this was permissible under the statutory framework. The Court also found that, while the Lee Dams were not multi-purpose dams, they were in fact operated with objectives which included flooding alleviation, holding at para. 109 that the ESB “tries, where possible, to reduce downstream flooding in a manner that does not detract from its hydro-electric purpose… By operating to TTOL, ESB combines optimal usage with substantial flood alleviation”.

3.6 The High Court considered that TTOL offers a level at which the generating potential at the Lee Dams can be optimised while ensuring that water levels are generally kept lower. The trial judge considered that, on the evidence before him, the obligation contained in the Lee Regulations was to endeavour to reach TTOL.

3.7 Having held that a duty of care was owed on the part of the ESB to owners or occupiers of downstream property, which required the ESB in its management and operation of the Lee Scheme not to cause unnecessary flooding, the trial judge considered that the practical expression of this duty of care was such as to give rise to a legal duty to maintain water levels at TTOL. “Unnecessary flooding” was held to be that which “occurs after ESB crosses the point of optimisation that it has itself identified as its top operating level”. The Court rejected the ESB’s submission that its duty is confined to not releasing more water downstream than that which is received into the Lee Dams, an iteration of the “do not worsen nature” rule which has been adopted in a number of US cases regarding the liability of dam operators. It will be necessary to return to those US authorities in due course.

3.8 The High Court accepted UCC’s contention that ‘nature’ in this case has been fundamentally altered by the construction of the dams and that the Lee Scheme represented a “new status quo”. The Court held the concept of “pre-existing nature” did not represent the expectation or understanding of downstream residents, in circumstances where it was considered that the Lee Scheme intermediated between ‘nature’ further upstream and their property. Distinguishing the other US dam cases cited to the Court, the trial judge followed People v. City of Los Angeles 34 Cal.2d 695; 214 P.2d 1 (1950), as judicial recognition of “changed nature” as the new condition to which regard must be had when considering the state of nature.

3.9 The trial judge went on to consider the nature of the ‘do not worsen nature rule’. The Court held that this represented a rule that derived from the building and ownership of a dam and the Court considered that it does not attempt to address the additional and distinct responsibility attaching to the harnessing of the river flow for industrial purposes. Barrett J. continued, at para. 1029:-

“It is a rule that does not reflect the development of the duty of care in the 20th century, or the rightful expectations of modern society. Moreover, it is not simply the case, as ESB claims, that during the flood of 2009 it merely allowed water to pass through the Lee Dams…To succeed in its 'do not worsen nature' argument, ESB must present itself as a 'passive agent' and nature as an 'active agent'. This is a distortion of the truth.”

3.10 In relation to the duty of care established, the Court then proceeded to find that foreseeability of the harm had been established as it was “common case” that high discharges created a risk to life and property of persons downstream. In addition, and from the particularised knowledge available to the ESB, the trial judge held that it was beyond dispute that the ESB was aware of that risk. A sufficient relationship of proximity between the parties was also found for UCC, as owner and occupier of land by the river, “fell clearly within the class of persons who would be directly affected by high discharges from the Lee Scheme”.

3.11 The High Court then proceeded to make several findings in respect of the evidence as to causation, holding first that, had water levels been maintained at TTOL, the peak flow of discharges on 19 November 2009 would have been reduced, resulting in benefits downstream. Further, it was held that, if advance discharges had taken place, peak discharge on 19 November would have been reduced appreciably. The trial judge also found that more effective use of storage at Carrigadrohid would also have reduced downstream flooding. Finally, the Court held that timely and effective warnings on the morning of 19 November would have meant that less damage would have been caused. Further, the Court dismissed the ESB’s contention that the flood was caused by nature, and not by the ESB as it did nothing to worsen the natural conditions that existed, on the basis that the scope of the duty of care should not be determined by reference to causation

3.12 The High Court then proceeded to outline a number of findings of breach of duty of care on the part of the ESB. The trial judge found, amongst other things, that water levels at flood-start in November 2009 were at a level that created an obvious risk of serious flooding downstream and were unreasonably maintained at such a level, given the time of year, the pattern of unsettled rainfall, the risk of heavy rainfall, the catchment saturation and advance discharge limitations. The Court also held that the ESB failed to react appropriately to the weather forecasts received and that, given the high levels of water and the extreme weather which had been forecast, the ESB ought to have discharged water earlier and in greater quantities in the days preceding 19 November. In addition, the ESB should reasonably have maintained lower water levels than it did by operating consistently to TTOL. The trial judge considered that the start water levels in a flood situation had a critical impact on ultimate discharges, thereby determining empty space and thus determining required discharge-levels. At para. 1075, the Court found that the ESB was negligent in keeping water levels as high as it did, placing the ESB in a position where its capacity to handle a large, reasonably foreseeable flood event was severely limited.

3.13 At para. 1078, the Court found that maintaining water levels at TTOL was consistent with maximising hydro-generation and that profit maximisation was “little enough reason” for keeping water-levels high. The trial judge then referred to the evidence of Mr. Matt Brown, an energy consultant called as a witness by UCC, which indicated that the value of the additional revenue earned by the ESB by operating above TTOL during November 2009 was between €100,000 and €130,000.

3.14 The High Court further found that the ESB was liable in nuisance, where it had consistently accumulated water in excess of TTOL and, as a result of this continued behaviour, the storage capacity in the Lee Dams had been significantly reduced. It had, therefore, become necessary to release water over a prolonged period at a rate that caused flooding downstream, thereby interfering with UCC’s use and enjoyment of its property.

3.15 Under a separate heading, the Court also found that ESB had a so-called “measured duty of care” as an occupier to remove or reduce the hazard which existed to neighbours, as established in Leakey v. National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty [1980] QB 485. The ‘hazard’ which the trial judge considered to exist was that of water levels maintained in excess of TTOL. Following the decision of the Privy Council in Goldman v. Hargrave [1967] 1 AC 645, the trial judge held that the duty’s existence was based on knowledge of the hazard, the ability to foresee the consequences of not checking or removing it and the ability to abate or reduce the hazard. The Court went on to hold that the standard required of the occupier ought to be that which is reasonable to expect of him in his individual circumstances. The ESB was held to have failed to do what it reasonably could and should have done to mitigate the nuisance. By deliberately releasing water, it had caused damage which could have been avoided or been significantly reduced by heeding weather reports and spilling earlier or, indeed, by operating consistently to TTOL. Maintaining water levels at TTOL was considered to be a reasonable action to minimise the known risk of flood damage to UCC from heightened discharges.

3.16 Under the measured duty of care concept, the Court held that generally it was necessary to be able to formulate as an injunction that which the plaintiff asserts the defendant was obliged to do. The trial judge defined this as follows at para. 953:

“ESB must never exceed TTOL and if, inadvertently, it does so, it must immediately take steps to reduce water-levels to TTOL. Or, a possible alternative mandatory form: ESB must treat TTOL as though it were MaxNOL.”

3.17 The High Court dismissed the contention that the ESB did not create the flood. Following Bybrook Barn Garden Centre Ltd. v. Kent County Council [2001] L.G.R. 329, the Court held that, in certain circumstances, a defendant can be liable for a nuisance that he does not directly create. In response to the ESB’s contention that nature caused flood-damage to UCC rather than ESB’s own want of care, the Court observed at para. 955 that questions of causation should not be conflated with the question of the duty of care, which should be assessed by reference to foreseeability, proximity, and considerations of what is just and reasonable.

3.18 In relation to the flood warnings which were issued by the ESB, the trial judge considered that the ESB had a duty of care to warn persons downstream, that there was “a heightened duty on the ESB to warn” those on the warning list and that the warnings which were provided to UCC were neither timely nor meaningful. At para. 269, the High Court set out the features which cast this heightened duty to warn on the ESB:-

“First, ESB assumed the responsibility of giving warnings to those on its warning list; the corollary of such an assumed responsibility is a heightened obligation towards those to whom that obligation is assumed. Second, ESB was the only entity capable of providing information on discharges. Third, ESB stood possessed of its knowledge of various flood studies.”

3.19 The Court then went on, at para. 276 of the judgment, to outline what it considered to be a number of deficiencies in warnings issued by the ESB on 19 November 2009. It was held that the warnings in question were not sufficiently differentiated from those provided on previous occasions involving less serious flooding risks. In addition, it was considered that there was no indication of the severity of the flood risk arising and that the warnings contained no significant indication of the likely impact of the increased discharges of water to property downstream in general and, specifically, in relation to the buildings of UCC. The trial judge held that it would have been “relatively easy for ESB to provide more effective warnings” and convey the full risk arising from the increased discharges. These observations led the Court to conclude that the ESB had a duty to provide “timely and adequate warnings” to a person to whom it had assumed a responsibility to so warn and that it had failed to discharge this duty. Having considered the evidence of UCC staff members, the Court held that, had they known what the discharges were to entail, there was more those staff members could have, and would have, done to limit the damage caused.

3.20 As already noted, Barrett J. also found UCC guilty of contributory negligence which he measured at 40%. However, as that aspect of the proceedings is not currently before this Court, it is not necessary to set out the findings of the High Court on that question at this stage.

3.21 It is next necessary to consider the reasons why the Court of Appeal came to the opposite view to that of the High Court.

4 The Judgment of the Court of Appeal

4.1 Having appealed the primary finding of Barrett J., the ESB were successful in the Court of Appeal in overturning the judgment of the High Court on the question of its liability. The Court of Appeal considered that the conclusions reached by the trial judge in imposing liability on the ESB in respect both of floodings and warnings were erroneous and that the appeal should be allowed. At para. 14 of his judgment, Ryan P. continued:-

“The High Court judgment if permitted to stand would represent a significant alteration of the existing law of negligence and nuisance, would be contrary to the statutory mandate of ESB in respect of electricity generation and would not be consistent with reason and justice.”

4.2 The Court of Appeal first considered the trial judge’s conclusions in relation to TTOL which, it stated, formed “a central pillar” of the judgment, being crucial to the reasoned process underlying the finding of the High Court relating to a duty of care to avoid unnecessary flooding. Ryan P. noted that the judgment specified TTOL as representing the precise standard of care to which the ESB must adhere as a result of that duty. At para. 117, the Court of Appeal held that the trial judge’s analysis of TTOL was erroneous. In the view of the President, TTOL was a guideline, expressed as a target, and did not enjoy any particular binding status on the ESB. The Court found that the ESB was required to operate the dams safely, but that a breach of its internal rules alone was not sufficient to establish negligence and, conversely, the fact of compliance with TTOL would not in itself be an answer to a claim in negligence.

4.3 The Court accepted the ESB’s case to the effect that a number of problems existed regarding the theory and practice of implementing the proposed rule of compliance with TTOL. These included issues concerning the ascertainment of when it was appropriate to allow the reservoir to fill beyond TTOL, the ability of the ESB to alter the provisions of the Lee Regulations and the TTOL standard. Fixing the level which the ESB was obliged to maintain in its reservoirs as TTOL was held to represent “a highly invasive and prescriptive approach to the management of the Lee Scheme”, which was incapable of general application and therefore the trial judge was held to have erred in making such a finding.

4.4 The Court of Appeal then proceeded to consider the compatibility of the statutory provisions governing the Lee Scheme with the duty to avoid unnecessary flooding identified by the High Court. Under s. 34 of the 1945 Act, the ESB had the power to alter the water level as it considered necessary in connection with the operation of the works. The Court of Appeal held that it followed from s. 10(1) of the 1945 Act that the purpose of the works was the generation of electricity. While flood alleviation was not prohibited by the 1945 Act, the Court held that such measures were only permissible to the extent that they did not impair the exercise of the mandatory functions of the ESB. The Court then held that, conversely, it would be impermissible under the Act to prioritise flood protection as a policy imperative over electricity generation as this would be contrary to the statutory scheme. Ryan P. concluded that, if the duty to avoid unnecessary flooding in practice meant maintaining extra storing space and mandating adherence to TTOL, this should properly be construed as an impermissible inhibition of the ESB’s capacity to carry out its statutory mandate.

4.5 Turning to consider whether there existed a duty to avoid or prevent unnecessary flooding at common law, the Court of Appeal first considered the existing case law concerning dam-operators and found that it did not support the duty claimed by UCC and imposed by the High Court, whether defined in general terms or in the specific form of an order to keep to TTOL. The Court considered persuasive the rule set out in Iodice v. State of New York 247 App. Div. 647 (1951), and other subsequent US dam cases, which held that the only duty imposed on a defendant dam-operator in respect of single purpose dams (like the Lee Dams) was to avoid making the flooding worse than it would be under natural conditions. The Court rejected the finding of the trial judge that the “do not worsen nature” rule was not applicable in circumstances of long-standing constructions that had permanently changed nature and held that, if that were the case, no development of any kind could make the defence that it was not adding to the existing situation.

4.6 The Court of Appeal then addressed the question as to whether the evidence before the courts meant that the ESB had accepted responsibility for carrying out flood alleviation so as to afford legal redress to parties downstream in the event that the ESB fails to carry out such a duty. At para. 179, it was concluded that the documents established in evidence did not disclose a basis for a conclusion that ESB, through its publications and statements, had accepted responsibility for a legally enforceable duty to operate the reservoirs in a manner that is specifically directed to alleviate downstream flooding. At paras. 184 and 185, Ryan P. held that no legally enforceable obligation to carry out flood alleviation arose by reason of the ESB’s previous conduct in operating the dams, which had had the effect of reducing flooding. The fact that a person or body had engaged in an act which was of assistance to another did not, without more, create a legal liability and, while its procedures and operating rules did envisage flood risk reduction, the Court held that it did not follow that the ESB had assumed legal liability to prevent some or all flooding to a specific standard.

4.7 The Court of Appeal disagreed with the trial judge’s conclusion that, in common law, a duty of care existed not to cause unnecessary flooding. Ryan P. considered such a formulation of the scope of the duty would create difficulties in principle and in practice. He held that the asserted duty to avoid unnecessary flooding was impermissibly vague and impractical. The Court held that it was unclear where the distinction lay between “necessary” and “unnecessary” flooding and that the obligation contended for by UCC amounted to “an affirmative duty to prevent nature from injuring others” which, in the Court’s view, was unsupported by existing case law. Ryan P. concluded at para. 197 that such a duty was wholly unspecific and unknowable in advance, yet also one which was difficult to measure in retrospect.

4.8 The Court of Appeal then proceeded to consider the claim in nuisance, or on foot of a measured duty of care under the Leakey jurisprudence, in circumstances where the negligence claim had failed. In the absence of any finding that the ESB was not in breach of any obligation that was owed to UCC under a duty of care, Ryan P. considered that it would seem to follow that the use of its land in connection with its function of electricity generation should be excused of fault. Whilst accepting that some lawful activity carried out on land in a non-negligent manner may give rise to interference with neighbouring land, the Court of Appeal considered that what was alleged in this case was not something arising incidentally from the operation of the business of the ESB but rather the modus operandi of the business itself. The Court considered that the nature of the case, the reasoning of the trial judge and the structure and emphasis of the judgment “all point to the centrality of negligence and the peripheral and essentially theoretical nature of the debate on nuisance”.

4.9 The Court considered that the essence of the liability under the Leakey duty was that a harm had come from the defendant's land and had gone on to, or was in danger of going on to, the plaintiff's land. The Court found that the central feature missing in the High Court’s analysis was that the ESB had done nothing to affect the state of the river that was passing in its channel through its land and that of UCC. Ryan P. concluded that there was no hazard on the ESB's lands that could be identified for the purpose of being corrected or removed and that the river was common to the lands of both parties. The Court of Appeal held that the Lee Dams were not, from the perspective of UCC, a danger, but rather gave rise to an improvement on conditions as they would have been if the dams had been absent. The water levels in the river had not been increased by ESB, nor had the ESB caused flooding and the flooding of UCC property could not be said to have emanated from the ESB. Rather, in the Court’s view, the flooding derived from the naturally occurring flood on the River Lee and consequently there was no basis in law for finding liability in nuisance. Thus, the Court of Appeal held that the determination of the High Court to the contrary effect ought to be set aside.

4.10 The Court of Appeal added that, as riparian owners, the parties are in a legal relationship with mutual obligations and rights. Under the principles of riparian law, a “lower” riparian proprietor such as UCC was obliged to accept the natural flow of the river and that this was consistent with the ESB discharging a duty to downstream occupiers and owners not to worsen nature. Ryan P. considered that it was unnecessary to look outside that scheme of riparian law for rules governing their conduct as riparian owners. On that basis it was also held that the High Court had erroneously imposed liability.

4.11 Finally, in considering the adequacy of the warnings issued by the ESB, the Court of Appeal considered in turn whether there had been an assumed responsibility to warn on the part of the ESB and whether there existed a common law duty to warn. The Court concluded in respect of the first question that, in light of its practice and conduct over the preceding years, once discharges from Inniscarra exceeded 150m3/s, the ESB had assumed the responsibility to give a general public warning through the relevant authorities and the media and had also undertaken to warn those on the opt-in warning list.

4.12 However, the Court then noted that there was nothing in the Regulations and no evidence before the Court of past conduct from which it could be inferred that the ESB had accepted responsibility to provide the type of information and warnings which the trial judge said were required to meet the obligations it had assumed. On that basis the Court concluded that warnings concerning the anticipated volume of discharges, where such discharges would likely end up, or the possible effect of any such discharges, were not required. The responsibility assumed by the ESB was held to be “no more than to forewarn those on its list that something out of the ordinary was about to occur and about which they needed to be concerned”.

4.13 The Court concluded that the fact of the ESB’s control of the dams and its knowledge of the potential consequences arising from discharges made had no effect on the extent of this assumed responsibility and that the High Court erred in concluding that there was an assumed responsibility on the part of the ESB to provide different and more detailed warnings based upon such factors. The Court was further satisfied that, in the absence of such a responsibility to provide individuated warnings concerning the likely impact of the discharges on certain properties, the ESB complied with its assumed responsibilities in providing two warnings to UCC on 19 November 2009 and that there was no basis in fact or law for the conclusion of the trial judge that the ESB had failed to comply with those obligations.

4.14 The Court of Appeal then turned to the question of whether the trial judge erred in law in concluding that the ESB owed a common law duty of care to the public at large to provide flood warnings and that the ESB owed a “heightened duty of care” in common law to those on its opt in warning list, including UCC. The Court was not satisfied that the ESB was under any duty at common law to provide a warning to all members of the public who were at risk of flooding from its dams, such that its failure to do so would give rise to an award of damages for those who did not receive such a warning. The ESB was dealing with the consequences of nature and was not doing anything to worsen the flooding. The fact that the ESB might anticipate a risk of potential flooding which could cause damage to downstream residents was held not to be sufficient to create positive duties or obligations. Therefore, the Court was satisfied that there was no legal basis for any broader duty of care than that which arose on foot of the ESB’s assumption of responsibility to provide certain limited warnings to those on its opt-in warning list.

4.15 As noted earlier, the Court of Appeal also held that Barrett J. was incorrect to hold UCC liable for contributory negligence. However, as that issue is not before this Court at present it is unnecessary to set out the reasoning of Ryan P. in that regard at this stage.

4.16 As also noted earlier, both sides sought leave to appeal to this Court, which leave, of course, forms the scope of the appeal to which this judgment is related. It is appropriate next, therefore, to turn to the grant of leave to appeal.

5 Leave to Appeal

5.1 In the determination of this Court (University College Cork - National University of Ireland v. Electricity Supply Board [2018] IESCDET 140), it was considered that the case raised novel issues of law which were of general public importance. It was further noted that UCC’s claim was one of almost 400 proceedings commenced against the ESB in respect of the flooding incident in Cork in November 2009. In granting UCC leave to appeal the decision of the Court of Appeal, the Court observed that:-

“The case addresses a number of issues including the liability of a dam operator in respect of persons or property downstream, the law relating to the existence of duty of care, the definition of any such duty and the liability of statutory undertakings both generally, and in the law of nuisance.”

5.2 Leave was also granted in respect of the cross-appeal lodged by the ESB against the decision of the Court of Appeal on contributory negligence but, as mentioned above, in the course of case management it was determined that the matter of contributory negligence was to be left over pending a determination of primary liability. Thus, it is only the main appeal against the finding of the Court of Appeal to the effect that the ESB was not liable in negligence or nuisance which is currently under consideration.

5.3 Against that background, it is appropriate first to set out in general terms the issues which arise on this appeal having regard to the judgments of both the High Court and the Court of Appeal.

6. The Issues - A General Approach and Three Areas of Contention

6.1 It seems to us that it is appropriate to group the issues into three main areas of contention.

(a) The Duty of Care

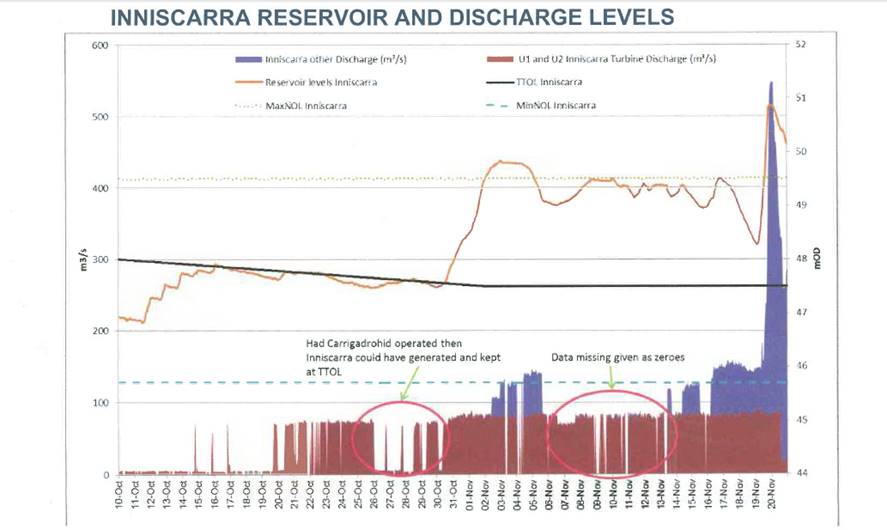

6.2 The first area relates to the claim in negligence. While a significant number of subsidiary issues potentially arise, it would appear that the central area of dispute between the parties concerns the extent, or scope, of any duty of care which the ESB could be said to owe to UCC or, indeed, other downstream owners and occupiers. It is perhaps appropriate at this stage to explain why the extent of the duty of care is so central to the issue of negligence in the circumstances of this case. There is annexed to this judgment a graphic which provides a useful synopsis of the water levels in the Inniscarra reservoir during the relevant period. While the matter is somewhat complicated by the interaction between that reservoir and the Carrigadrohid reservoir, it is sufficient for present purposes to concentrate on the Inniscarra reservoir which was, after all, the reservoir furthest downstream and which, in conjunction with the Inniscarra dam, provided the final barrier to water descending further towards Cork city. As the analysis which follows is designed purely for illustrative purposes, it is unnecessary, for the present at least, to consider any additional complications which might arise from the interaction between the two systems. The graphic is taken from the evidence and contains some commentary from the parties. However, it is the underlying data on which we comment.

6.3 From the Inniscarra graphic, it is clear that the water levels on 10 October 2009 were at a level which was somewhat below TTOL. It is also clear that there was little or no generation of electricity at that time, so that the water level was able to rise to TTOL by approximately 16 October and remain there until generation commenced around 19 or 20 October. It is then clear that the water level was able to remain at TTOL as a result of the use of water for generation purposes between 20 and 26 October and that the level further remained at TTOL until the end of October, during part of which period there was little or no electricity generation although, during the latter days of the period in question, generation did occur.

6.4 It is then clear that a very large quantity of water came into the system between the very end of October and approximately 2 or 3 November, leading to a very significant increase in water levels so that same ultimately exceeded MaxNOL. As noted earlier, the Regulations required spillage once MaxNOL had been exceeded, such that, for a period of some three or four days in early November, spillage occurred which had the effect of reducing the level of water slightly below MaxNOL. There then followed a fairly critical period between 6 November and approximately 14 November. During that period, there was more or less full generation of electricity, such that the 80-85 m3/s volume of water required for that purpose was being utilised. However, there was no spillage. Having regard to the amount of water coming into the system, the effect of the operation of the dam in that way was that the level of water remained at or close to MaxNOL for all of that period, meaning that, when a weather warning was issued on 16 November, the starting position was that the level of water was more or less at MaxNOL.

6.5 As a consequence, the system had no capacity to absorb more water than it could discharge, for to do so would have led to the water levels exceeding MaxNOL, with all the danger to the integrity of the dam which that entailed. Obviously, in those circumstances, an inflow of up to 150 m3/s could have been dealt with by a combination of electricity generation and spillage without the risk of flooding. However, the inflow greatly exceeded that amount, such that the spillage in turn was required to greatly exceed the amount which could be accommodated within the channel of the river downstream. In those circumstances, it was inevitable that flooding would occur.

6.6 Without addressing for the moment the key question as to whether any legal obligation lay on the ESB to anticipate and alleviate such a situation as it developed, it seems clear on the facts that, had the ESB spilled up to a combined generation and spillage usage of 150 m3/s between 5 November and 16 November (or at least done so in a quantity sufficient to bring the level down towards or to TTOL), the systems of the Lee Dams would have had a much greater capacity to absorb the huge inflow of rainwater which occurred on 19 and 20 November.

6.7 On the other hand, it is equally clear that at no stage was the outflow from the Lee Dams in excess of the inflow, except during a period when the combined generation and spillage quantities were nonetheless below the 150 m3/s threshold for flooding. The fact that there were some periods where a greater volume exited the system than had entered it can be seen from the fact that the overall level did drop on certain occasions due to the use of spillage. But during those periods when the outflow exceeded the inflow, it is clear that the total outflow did not exceed 150 m3/s.

6.8 It therefore also seems to be clear that, if the duty of care which the ESB might be said to owe towards owners and occupiers downstream from the Lee Dams did not extend beyond a situation whereby they would not, as it were, worsen nature (or at least would not do so to the extent that it might cause flooding by discharging water of a quantity beyond the 150 m3/s threshold), then it is hard to see how the ESB could be said to be in breach of any such duty of care.

6.9 Put simply, that analysis leads to two conclusions. If the ESB had a duty of care to engage in some form of proactive discharge, having regard to all of the circumstances of the case, then it is almost certain that the ESB was in breach of that duty of care. However, it can equally be said that, if the duty of care of the ESB did not extend beyond a “not worsen nature” obligation, except where additional outflows over the inflow would not cause flooding, then it is also clear that it would be very difficult to see how the ESB was in breach of that duty of care.

6.10 For those reasons, it was hardly surprising that a great deal of the debate between the parties, both in the written submissions filed and at the oral hearing, centred very much on the extent of any duty of care which the ESB might be held to owe to downstream owners and occupiers, for the resolution of that issue was bound to go a very long way indeed towards resolving the question of whether there was negligence.

6.11 The first area of contention, therefore, concerned UCC’s argument relating to the scope of the duty of care which rested on the ESB. If UCC’s argument in that regard is accepted, then the latter company was almost certainly in breach of such duty and thus negligent. On the basis of the ESB’s contended for duty of care, the ESB was almost certainly not in breach and thus not negligent.

(b) Nuisance

6.12 The second area of contention concerned the potential liability of the ESB in nuisance, or under the Leakey jurisprudence. As will become clear when it is necessary to discuss in detail the jurisprudence in relation to the duty of care in a case such as this, a significant distinction is made in the law of negligence between acts of commission or acts of omission. In the most recent case law, the distinction is made between acts which do harm, as opposed to a situation where there is a failure to do good.

6.13 However, under the Leakey jurisprudence, it is possible in some circumstances that liability will arise, even in cases where there is no positive action taken by the defendant which could be said to have caused harm. Thus, the issues which arise under this heading only really become relevant in circumstances where a court declines to fix a defendant with a duty of care on the basis that no positive obligation to do good exists in the context of the duty of care asserted. In that sense, the nuisance/Leakey issues are more properly to be considered as part of a fall-back position, only coming into play in the event that the duty of care issue is resolved in favour of the ESB.

(b) The Warnings

6.14 Similarly, but for somewhat different reasons, the third area of contention, being the warning issue, also represents a fall-back position. It would seem that the obligations which UCC contend lay on the ESB, either under the contended for duty of care or under the law of nuisance and the Leakey jurisprudence, appear to be the same in the circumstances of this case. Liability under either heading would appear to be likely to give rise to the same damage. However, the same is not at all true if the only head of liability established concerned the absence of warnings. There was evidence given on behalf of UCC to the effect that certain measures could have been taken which would have alleviated the flood damage, had the sort of warnings which UCC contended were required actually been given. However, it seems clear that the extent to which those measures could have alleviated the damage to UCC would have fallen a long way short of the extent to which damage might have been prevented by the sort of measures which UCC assert were required in order to meet the duty of care allegedly borne by the ESB, or might have resulted from the contended for failure of the ESB in respect of nuisance and the Leakey jurisprudence. If the case were to succeed on either of those latter bases, then the damage for which compensation would require to be ordered would inevitably include all of the damage which would be attributable to a finding of a negligent failure to give warnings but also much more damage besides.

6.15 In the light of all of that analysis, it seems to us that the most appropriate starting point must be to analyse the arguments put forward by both parties on the issue of the duty of care and to determine the scope of any duty of care which UCC owed in all of the circumstances of this case. We turn to that question.

7. The Duty of Care - the arguments

7.2 The ESB contends that the “primary and inescapable fact of this case” is that the flooding suffered by UCC in November 2009 was considerably reduced by the operation of the Lee Dams and was significantly less than it would have been in the absence of the dams which, it is said, had reduced the flow of the river downstream. The ESB accepts a duty of care to persons downstream in respect of flooding which is caused when the outflow of the Inniscarra Dam exceeds the inflow to the reservoirs. It further accepts a duty of care to persons downstream to maintain the integrity of the Lee Dams. However, the ESB argues that their actions in pursuing hydrogeneration did not cause flooding and the risk of flooding was not attributable to the ESB because, it is said, the source of the flooding downstream was nature. In that context, no duty of care to alleviate such flooding is said to arise.

7.3 Within those broad parameters a number of specific issues arose for debate between the parties. The starting point for any consideration of the extent of the duty of care in the law of negligence in this jurisdiction must be the decision of this Court in Glencar Exploration plc v. Mayo County Council (No 2) [2002] 1 IR 84. The basis for establishing a duty of care requires that damage be suffered which was both foreseeable and not unduly remote from the acts causing it. In addition, it is suggested in Glencar that it is necessary that it be considered just and equitable that a duty of care be extended in all the circumstances of the case. To a very great extent there was no dispute between the parties as to the principles identified in Glencar although there were very significant differences indeed as to how those principles should apply in the circumstances of this case. Insofar as there may have been a slight difference of emphasis between the parties at the level of general principle, the ESB relied on what it contended was the approach of the courts in the United Kingdom to the effect that, where it is sought to extend a duty of care into an area which has not been the subject of detailed judicial examination, it is appropriate first to consider whether a duty of care should be held to exist (and if so to what extent) by analogy with other areas which have been the subject of more detailed judicial consideration. Put another way, it is argued that the question of whether it is just and equitable to impose a duty of care in a particular circumstance should be approached by considering whether a duty of care has been identified in analogous circumstances. This is the first issue to which it will be necessary to return.

7.4 On the question of foreseeability, UCC argues that it was foreseeable that any failure of the part of the ESB to manage the Lee dams in a way designed to minimise downstream flooding could lead to there being more flooding than might otherwise have arisen. In those circumstances it was said that the foreseeability test was met. In like manner it was said that downstream flooding was sufficiently proximate to any failure to manage the Lee Dams in a manner designed to minimise downstream flooding so that the proximity leg of the test was also met.

7.5 However, in response, the ESB sought to place reliance on the fact that, at no relevant time, was the down-flow of rainwater beyond the Lee dams greater than the in-flow. In those circumstances it was argued that, in reality, neither foreseeability nor proximity really arose at all, because any allegation of wrongdoing amounted to what was said to be an omission on the part of the ESB to take positive action to prevent flooding rather than the commission by the ESB of a wrongful act which caused that flooding.

7.6 This dispute gave rise to a second major issue before the Court being as to the proper characterisation of the duty of care said to be owed by the ESB to UCC. While it will be necessary to turn to a more detailed consideration of the law in that regard in due course, we have already noted that there is a well-established aspect of the law concerning the duty of care in negligence which distinguishes between acts of commission and acts of omission. While it is accepted on all sides that there are exceptions to the general proposition, it nonetheless is clearly the case that the imposition of a duty of care which imposes a positive obligation to act to prevent damage arises in significantly more limited circumstances than those which impose a duty of care to refrain from acting in a way which may foreseeably cause proximate damage.

7.7 In one sense that question, as many in law, came down to one of characterisation. The way in which the Lee dams operate, as a matter of practise, was not in significant dispute. UCC sought to argue that the ESB could not be equated to the bystander who simply fails to act to prevent harm being done to a third party. In that regard UCC sought to place reliance on the fact that the ESB carries out activities which have, as their inevitable consequence, an interference with the flow of water downstream. The argument in this area centred on whether that activity on the part of the ESB was sufficient to take it out of the category of a party who could successfully argue that what was being asserted against it was an alleged duty of care to take positive action.

7.8 UCC submitted that, as the ESB maintains the Lee Dams as part of an industrial process in which the control of water levels and discharges of water comprise of positive actions taken by the dam operator, the ESB cannot properly be characterised as a simple third party. The law on omissions is said to involve strangers to the chain of events, who have no involvement in the relevant activity, whereas here the ESB is said to have failed to take reasonable care while acting in the course of an activity which is of the utmost relevance to the subsequent events. UCC submits that, if the Court does, however, regard this as an omissions case, the ESB is liable on the basis of the exceptions to the general principle on omissions which, it is argued, were correctly set out by the United Kingdom Supreme Court in Robinson v. Chief Constable of West Yorkshire Police [2018] AC 736, at para. 34 in the following terms:-

"In the tort of negligence, a person A is not under a duty to take care to prevent harm occurring to person B through a source of danger not created by A unless (i) A has assumed a responsibility to protect B from that danger, (ii) A has done something which prevents another from protecting B from that danger, (iii) A has a special level of control over that source of danger, or (iv) A's status creates an obligation to protect B from that danger."

7.9 Here, it is submitted by UCC that the ESB has met three of these categories, having assumed a responsibility to protect downstream property-owners from the risk of flooding, having a special level of control over the source of the danger, which is the river, and having a status which creates an obligation to protect downstream property owners from danger.

7.10 It was submitted by the ESB that its actions in November 2009 should be properly characterised as a “failure to confer a benefit” rather than being assessed as either an act or an omission. Thus, ESB argues that UCC’s case should properly be considered as the proposal of a duty to improve the situation for those downstream, or to “confer a benefit” to downstream property-owners, by alleviating flooding. The ESB relies on the distinction drawn in the recent judgment of the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom in Poole Borough Council v. GN [2019] UKSC 25, between cases where the defendant has caused harm to the plaintiff, on the one hand, and those where the defendant has failed to improve matters for the plaintiff, on the other. The ESB submits that the law of negligence generally imposes a duty not to cause harm rather than a duty to provide other persons with a benefit.

7.11 In response to the exceptions to the law on omissions, as set out in Robinson, which do give rise to a duty to improve matters or to protect against harm caused by a third party, the ESB suggested that the concept of a “special level of control” arises from being the source of the relevant risk and having a consequent obligation to arrest such a risk. UCC, on the other hand, submitted that the concept of “control” is not confined to circumstances in which the hazard is created by the defendant, or where the hazard is brought onto relevant land, particularly where the ESB obtains the benefit of that control.

7.12 As regards the assumption of the proposed duty of care, it is UCC’s case that ESB voluntarily assumed responsibility to alleviate flooding and that, therefore, it is “… unnecessary to undertake any further inquiry into whether it would be fair, just and reasonable to impose liability”, as stated at para. 35 of Commissioners of Customs and Excise v Barclays Bank [2007] 1 AC 181. UCC relies on the findings of the High Court in respect of the representations made by the ESB regarding flood alleviation and in respect of the reliance placed by those downstream on these representations. It submits that the Court of Appeal did not engage with these issues. UCC further submits that a court does not require evidence of specific reliance and can instead establish a general reliance, as set out in the judgment of Lord Hoffmann in Stovin v. Wise [1996] AC 923, following the decision of Mason J. in Sutherland Shire Council v. Heyman (1985) 157 CLR 424. This doctrine refers to general expectations in the community, which the individual may or may not have shared, that a statutory power will be exercised with due care. The management of the Lee Dams in order to minimise flooding was said to be both uniform and routine and, therefore, it was argued, the expectation downstream was that the River Lee would not flood beyond a certain level.

7.13 In response, the ESB argued that the approach of the Court of Appeal in relation to the assumption of responsibility was correct. It was submitted that there was no acceptance of responsibility for flood alleviation in the sense contended for by UCC. It was also argued that the conduct of the ESB was such that it could be said to have tried to do what could be done to alleviate flooding without impairing the legitimate prioritisation of its hydroelectric function. ESB also contended that there cannot be any voluntary assumption of responsibility giving rise to the imposition of liability without reliance. It was said that there was no evidence of reliance in that UCC never sought any information from the ESB about the dams and never saw many of the documents which it now relies on, all of which documents reiterated that the Lee Dams did not protect against all flooding risks. Reliance was placed in that regard on the statement of Lord Hoffmann in Stovin v. Wise to the effect that, in order for the doctrine of general reliance to be applied, it must be possible to “describe exactly what the public authority was supposed to do”. The ESB submitted that there is a lack of such specificity in relation to any obligation in respect of flood alleviation in the obligation which UCC urged on this Court.

7.14 Turning to consider the effect of the 1945 Act, UCC submitted that, if the decision of the Court of Appeal is correct, the statute mandates the production of electricity at maximum profit, even if that is at the expense of the safety of persons downstream. UCC contended that the statute would have to be explicit if production of electricity was to override safety considerations and that, in accordance with the principles advanced by Clarke C.J. in his minority judgment in Cromane Seafoods Ltd. v. Minister for Agriculture, Fisheries and Food [2017] 1 I.R. 119, the mere fact that this case involves a statutory body does not prevent the Court from ascertaining whether a duty of care should be imposed in the circumstances of the case. This was said not to be a situation where exposure to liability for damages would have a prejudicial impact on the public interest. UCC argued that it does not seek to impose a greater liability here than that which would be imposed on a private individual in the conduct of industrial activities.

7.15 That the ESB “shall generate” electricity, as required by s. 10 of the 1945 Act, could not, it was said, be read as conferring a duty to exclusively pursue hydrogeneration for commercial gain or to generate continuously. In that context a number of findings of the High Court were relied on being those to the effect that the proposed duty of care to alleviate flooding is not inconsistent with generation and that the ESB has in the past actively compromised its hydroelectric function to some extent so as to provide flood alleviation. Further, it was said that the ESB never undertook a proper risk assessment of any scenario other than the design flood in order to assess whether generation had to be supressed in a manner which was inconsistent with the statutory duty.

7.16 UCC further relied on Condition 19 of the ESB’s generation licence, which has statutory force, to the effect that its statutory duties do not translate to an obligation to generate electricity in all circumstances, or in priority to all other considerations.

7.17 The ESB relied on the High Court’s rejection of the contention that the Lee Dams were multi-purpose dams to suggest that their sole statutory purpose is hydrogeneration and to support the Court of Appeal’s finding that the proposed duty would require the ESB to engage in a type of flood alleviation in direct conflict with hydrogeneration. It was submitted that the law as set out in Poole Borough Council is clear to the effect that the existence of a discretion under s. 34 of the 1945 Act to alter water levels in order to alleviate flooding and, in doing so, to confer a benefit to persons downstream, does not mean that a common law duty to exercise the power for their benefit arises.

7.18 While some flood alleviation is possible without compromising the statutory objective of hydrogeneration, should the proposed duty of care be imposed on the ESB, it was submitted this would create a fundamental tension between its statutory function and the duty to engage in flood alleviation, which would be exacerbated by what was said to be the lack of clarity on UCC’s case surrounding the appropriate level of available capacity and the standard of care to which the ESB should be held. On this basis, it was suggested that the discharge of both duties is incompatible.

7.19 Charged with the complaint that the proposed duty of care suffers from vagueness, UCC maintained that there would be no difficulty in imposing liability for only that flooding which could have been avoided by the exercise of reasonable care (being flooding which is therefore considered “unnecessary”). It was submitted that the ESB is in a position to manage its water levels and discharges with reasonable care, thereby avoiding entirely or minimising flooding and the risk to life and property downstream.

7.20 Further, UCC contested the Court of Appeal’s characterisation of its case as turning on TTOL. Rather, it submitted that, on the facts of this case, water levels were too high in the prevailing conditions and ought to have been lower. TTOL was used as a benchmark to establish a breach of the duty of care and was merely demonstrative of causative effect. It was said that, had water levels been kept to TTOL, significant flooding would have been avoided. UCC argued that the ESB should manage water levels according to the “as low as reasonably possible” principle, by predicting the frequency and magnitude of the risk of flooding, by means of risk assessment models. The actions which the ESB takes in the generation process and in safeguarding the integrity of the dam ought also to have been taken in the broader context of other safety risks. If the risk is unlikely, there is nothing to prevent the ESB from conducting operations in the normal way. UCC suggested that the Court is not asked to fix a standard which applies to all cases but merely to assess whether the ESB has acted reasonably in all the circumstances of the case.

7.21 In contrast the ESB submitted that a number of issues arise in attempting to impose a standard of action that is “necessary” or “reasonable” where the ESB does not create the source of the risk of flooding. The decision as to what flooding is “necessary” and “unnecessary” is said to affect a number of persons downstream and the lack of certainty over the standard of care required of the ESB was argued to raise a number of questions as to the practical operation of the proposed duty of care. It was reiterated that the conception of TTOL as an “optimal” level is plainly wrong and that to maintain water levels at or below TTOL would have been costly to the ESB. Further, the ESB argued that to a finding that water levels were too high must be made by reference to some standard. The relevant obligations cannot, it was said, be entirely divorced from any metric of assessment.

7.22 A further aspect of the debate on this aspect of the case centred on the argument put forward by the ESB to the effect that its only obligation could be to “not worsen nature”. ESB suggested that the imposition of a duty of care which went beyond an obligation not to leave those downstream in a worse position than they would have been had the river flown uninterrupted by any ESB works would amount to the imposition of a positive duty to prevent harm rather than what was said to be the appropriate limitation on the duty of care which was to refrain from conduct which might cause harm.

7.23 Insofar as the “just and equitable” leg of the test identified in Glencar is concerned UCC advanced a number of points which, it was argued, ought lead the Court to conclude that this aspect of the test was also met.

7.24 First, insofar as there might be a question as to whether the duty of care asserted was an established category of same, or at lease analogous to such an established category, UCC argued that their position was supported by the decision of the UK Supreme Court in Robinson, which was said to endorse the proposition that physical loss resulting foreseeably from positive conduct constitutes such an established category of duty of care, at least in some cases.

7.25 Against that proposition ESB argued that its conduct could not be characterised as positive conduct in the first place on the basis, already alluded to, that the evidence established that at no relevant time was the outflow from the Lee dams greater than the inflow.

7.26 In like manner, while UCC submitted that the imposition of a duty of care on a dam operator was established in M.J Cordin v. Newport City Council QBD (TCC) 23 January 2008. However, it was argued by the ESB that the purpose of the dam in that case was flood control which purpose was said to be the basis on which a positive duty of care not to expose persons downstream to a foreseeable risk of flooding was said to arise.

7.27 On the basis of those arguments, the ESB asserted that there was no established case law which extended a duty of care to the operator of a dam (which did not have as its specific purpose the alleviation of flooding) which required such an operator to take reasonable steps to prevent downstream flooding by adjusting its operations to minimise the risk of such flooding. As a result of those arguments, the parties then passed to consider the factors which were said to be potentially relevant to the Court’s assessment of whether the general “just and reasonable” test had been met.

7.28 In that context UCC submitted that it was just and reasonable to impose liability on the ESB which was an entity engaged in what is said to be a hazardous industrial process so that it must be obliged to take reasonable care in its operations not to cause injury or damage. UCC relied on a number of bases for that general contention.

7.29 First, it was argued that the ESB had extensive knowledge of the risks of flooding to those downstream and exercised significant control over river levels. Second it was said that the ESB operated, and has held itself out as operating, the Lee Dams with a view to minimising flooding. Third, it was said to be noteworthy that, on the evidence, the proposed duty of care would have involved a very limited loss of revenue to the ESB and it is said that the ESB is not entitled to put profit before the safety of those downstream: Finally, it was argued that the duty suggested is not a particularly onerous one, as the decisions that the ESB were being asked to take in exercise of the proposed duty of care were the very decisions that they were already taking in the operation and control of the dam.

7.30 UCC further submitted that it would be inappropriate that the sole duty of care on the part of the ESB should be confined to one limited to guard against the collapse of the dam. Thus, it was argued, a dam operator would not be liable even if it knew that its activities were likely or certain to cause risks to the prejudice of all those downstream. The ESB is a statutory corporation which, it is said, cannot be distinguished from private competitors and which is generating electricity for its own economic benefit, rather than a public authority which is exercising its powers for the benefit of the community. In these circumstances, it was said that the ESB takes the benefit of the Lee Dams and must take the burden, which is to take reasonable care for the safety of persons and property downstream.

7.31 In response, the ESB restated that it can only be properly said to be a cause of flooding if it increases the flow of the river, that is, if outflow from the dams exceeds inflow in such an amount that flooding results. The ESB maintained that it did not produce harm and did not aggravate the harm so that the flooding was not, therefore, a consequence of the activity undertaken by the ESB. It was said that the risk of the flooding which actually occurred and which caused damage to UCC was created by the river. UCC was said to deliberately conflate risks attributable to ESB with risks due to the river itself.

7.32 The ESB submitted that, for this Court to fix a level of water at the Lee Dams for the purpose of flood alleviation would be an inappropriate incursion into policy making which would affect the rights of every person along the river and in particular those who would, on UCC’s case, be lawfully or “necessarily” flooded.

7.33 The crux of the defence case, therefore, that outflow has not exceeded inflow, is rooted in the “do not worsen nature” rule, as established in a number of cases involving dam operators in other jurisdictions, such as Iodice, Greenock Corporation v. Caledonian Railway [1917] AC 556 and East Suffolk Rivers Catchment Board v. Kent [1941] AC 74. UCC submitted that there are a number of problems with this standard, the primary one being that it is said to be a notional artifice which assumes that there is some hypothetical pre-dam standard of nature which no longer exists whereas, in truth, the dam itself has altered nature. The ESB is said to be now interposed between nature and those downstream, taking the benefit of the hydrogeneration and therefore is in a position in which it can control flooding and contribute to the safety of persons downstream.

7.34 It is also argued that the “do not worsen nature” rule does not account for the natural attenuating effect of the river valley or for peak flow in downstream tributaries, or high tide downstream, which means discharges may effectively worsen nature.

7.35 The ESB rely on a number of US, Canadian and UK cases to support the contention that it is a universal rule that the obligation of dam operators is confined to one which requires avoiding worsening a natural hazard, authorities which UCC contests are not easily transferable to this jurisdiction, given which is said to be their non-engagement with the constituent elements of the duty of care.

7.36 It thus follows that a key element of the argument put forward on behalf of ESB on the “just and reasonable” leg of the Glencar test really came back to the proposition that it has no obligation beyond not worsening nature.