Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

High Court of Ireland Decisions

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> High Court of Ireland Decisions >> Webster & Anor v Meenacloghspar [Wind] Ltd; Shorten & Anor v Meenacloghspar [Wind] Ltd [No.2] (Approved) [2025] IEHC 300 (27 May 2025)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/ie/cases/IEHC/2025/2025IEHC300.html

Cite as: [2025] IEHC 300

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

harp graphic.

THE HIGH COURT

[2025] IEHC 300

Record Number: 2018 8457P

BETWEEN:

MARGARET WEBSTER AND KEITH ROLLO

PLAINTIFFS

AND

MEENACLOGHSPAR (WIND) LIMITED

DEFENDANTS

AND

Record Number: 2018 8458 P

BETWEEN:

ROSS SHORTEN AND JOAN CARTY

PLAINTIFFS

AND

MEENACLOGHSPAR (WIND) LIMITED

DEFENDANTS

JUDGMENT of Ms. Justice Emily Egan delivered on the 27th day of May, 2025

INDEX

Issues arising for determination at module 2. 3

The delineation of the evidence for module 2. 6

Nature of the disputed new evidence. 7

Application of legal principles in relation to the admissibility of new evidence. 10

Justification advanced in Mr. Carr's report 11

The IEC does not meet the lacuna identified in para. 375. 11

The IEC is not the disputed new evidence. 11

Conclusion on criterion 1 of Murphy v. Minister for Defence. 14

Is the disputed new evidence admissible qua baseline assessment?. 14

The disputed new evidence would not substantially impact or alter my finding on liability. 16

The disputed new evidence does not undermine this court's finding on dominance. 17

Argument inconsistent with the defendant's position at module 1. 17

Lacuna: WEDG 2006 does not address thump AM.. 17

WEDG 2006 was not drafted with nuisance in mind. 17

WEDG 2006 was not drafted with AM in mind. 18

WEDG 2006 is under review and takes no account of low frequency WTN. 18

WEDG 2006 takes no account of night time background noise levels. 18

S. 28 is not the yardstick of nuisance. 19

WEDG 2006 does not address most of the Defra criteria. 20

The Phase 2 penalty scheme is under review.. 20

The IEC does not apply the Phase 2 penalty scheme. 20

Plaintiffs' further argument: the Carr comparative exercise misapplies the Phase 2 penalty scheme 21

Evidence of Mr. Stigwood, plaintiffs' acoustician. 26

Misinterpretation of the principal judgment 26

Has the 1,600 mode abated the nuisance?. 26

Other evidence from Mr Stigwood relevant to the potential abatement orders this court might make 28

Evidence of Mr. Mayer, Mechanical and Automotive engineer 29

Evidence of Mr. Carr, defendant's acoustician. 29

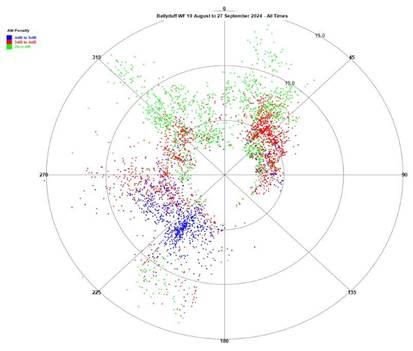

Figure 5: IOA RM results - 2024 1,600 rear garden 24 hour data. 30

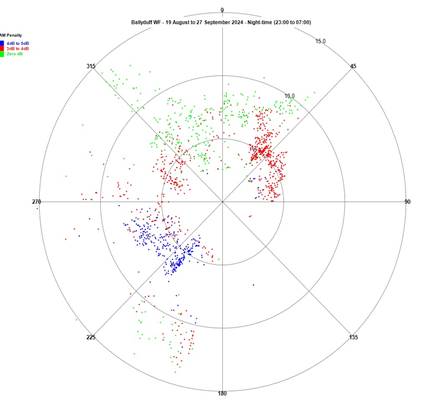

Figure 6: IOA RM results - 2024 1,600 mode rear garden night-time (23:00 to 07:00hrs) data 31

Table 3: 2024 1,600 mode rear garden 23:00 to 04:00hrs data- downwind only. 31

Has the 1,600 mode abated the nuisance? Onus of proof 33

Findings of fact regarding the 1,600 mode. 33

Analysis and findings of fact relevant to the potential abatement orders this court might make 34

Are the plaintiffs entitled to an injunction?. 38

Relevance of the public interest. 40

Windspeeds of 5 m/s to 7m/s inclusive. 43

Windspeeds of 10 m/s and 11 m/s. 44

Windspeeds of 12 m/s and above. 45

Summary of judgment

The plaintiffs maintain that this lower power mode has not abated the nuisance and seek an order directing the shutdown of T2 during sensitive periods. The defendant's principal argument is that the WTN does not pose a nuisance even in its "full" power mode and that no mitigation is therefore required.

The defendant sought to adduce new evidence to persuade the court to revisit the finding on liability made at module 1. This new evidence comprises an analysis of the raw noise monitoring data presented to the court by the plaintiffs in the course of module 1. The defendant contends that this shows that, even allowing for amplitude modulation ("AM"), [1] the WTN levels are lower than the noise limit fixed by current Irish planning guidance on wind energy developments (WEDG 2006).

I have determined that this new evidence could with reasonable diligence have been obtained for use at module 1. I reject the defendant's argument that a new technical specification on noise measurement techniques provides scientifically robust guidance on what level and nature of WTN causes unacceptable interference with residential amenity. I also conclude that the defendant's new evidence does not comprise a useful or complete baseline assessment for the purposes of crafting abatement measures. I further find that, even if admitted, the defendant's new evidence would not substantially impact or alter my finding on liability. I therefore decline to admit this evidence or to revisit my finding on liability.

As such, I have not found it necessary to decide whether the plaintiffs are correct in their argument that the new evidence does not in fact show that night time WTN levels are within the noise limits fixed by WEDG 2006, as contended by the defendant.

After reviewing the evidence I find as a fact, on the balance of probabilities, that the lower power mode trialled by the defendant does not ameliorate the nuisance. Applying the principles set out in Shelfer v. City of London Electric Company, I hold that the plaintiffs are entitled to an injunctive remedy.

Renewable energy is of benefit to the public, which is of relevance in crafting an injunctive remedy. Therefore, if I can be satisfied that measures short of the complete shutdown of T2 during sensitive periods would abate the nuisance, it is appropriate to fashion a remedy accordingly.

I then consider what form of injunction is just in all the circumstances of the case. It seems that the only potential way to abate the nuisance is to reduce noise levels (at relevant windspeeds/wind directions) by a clearly noticeable degree. A 5dB reduction or increase is thought to be an easily noticeable noise differential. However, to simply order a 5 dB reduction in the WTN would require further extended monitoring and ongoing court supervision. It would also lead to further dispute and continuing nuisance. I therefore prefer to proceed by restricting the operation mode of T2 provided this can, when necessary, reliably and consistently reduce WTN by 5dB.

I am satisfied that it is reasonable to restrict T2 to certain lower operating modes during quiet waking hours at certain wind speeds and wind directions. However, this would not be an acceptable solution during night hours. This is partly because I am not satisfied that the noise level reductions which are predicted to occur by altering the power mode of the turbine can be reliably and consistently achieved at night. It is also because constant sudden changes to the WTN at night, as the wind rises and falls, would have a jarring effect, disturb sleep and thus cause ongoing nuisance. I therefore order the shut down of T2 at night for windspeeds of 5m/s to 11 m/s inclusive in those wind directions associated with high AM values and thump AM.

Issues arising for determination at module 2

1. On 14th July 2022, O'Moore J. directed a modular trial of this nuisance action. Module 1 was to determine the issue of liability for nuisance. If required, module 2 would then determine the appropriate remedy and quantum of damages for nuisance.

2. The trial of Module 1 concluded on 6th November 2023. By judgment of 8th March 2024 ("the principal judgment"), I held that one of the two turbines operated by the defendant ("T2"), caused a nuisance to the plaintiffs during night hours and quiet waking hours ("sensitive periods"). Although a "narrow judgment call", I decided that the wind turbine noise ("WTN") could be tolerated during other times.

3. I was satisfied that, on the majority of the audio recordings, the WTN is the only noise that one can consistently hear. It was also clear from the audio recordings that the WTN displayed the particular intrusive characteristics complained of by the plaintiffs such as "erraticism, impulsivity, excessive AM values and thump AM". [2] I was also satisfied that the clear and unavoidable conclusion from the audio recordings taken by the plaintiffs' experts was that their external and internal soundscape was dominated by the WTN. In all likelihood, this dominance arose from a combination of the level of exceedance of the WTN over background noise levels, its high AM values, its comparatively low spectral frequency and its other attention drawing characteristics. [3]

4. I found that two features in particular contributed towards this dominance rendering the WTN an unreasonable interference: first, frequent and sustained periods of AM values widely acknowledged to be associated with high levels of annoyance and second, thump AM which, together with its associated vibration, was the most intrusive quality of the WTN.

5. In the principal judgment, I determined that the dominance of the WTN which was evident on the majority of the audio recordings was not a constant state of affairs. On the contrary, the nature of WTN is that periods of adverse impact are likely to be intermittent. However, I accepted that adverse impact occurs commonly, persists for sustained periods, and would be particularly evident at night.

6. Liability having been determined, remedy and quantum of damages would require to be adjudicated in module 2.

7. In the principal judgment, I found that due to the complex range of interrelated causative factors, [4] identifying the conditions under which unreasonable adverse impact arises and devising mitigation measures would be an iterative exercise. As noted by the defendant's expert, Mr. Carr, mitigation of WTN is often a process of trial and error. This is best approached on site and not in a courtroom. A court order is an unsuitably blunt instrument with which to tailor a remedy to address WTN nuisance without unnecessarily inhibiting the operation of T2. In light of the social utility of renewable energy, I would not order the shutdown of T2, even just at sensitive periods, if a more tailored solution could ameliorate the nuisance. I therefore directed the parties to engage in mediation in an attempt to agree appropriate mitigation measures to abate the nuisance in advance of module 2.

8. The mitigation exercise subsequently ran from 15th July to 30th September 2024. The defendant trialled just one potential mitigation measure. T2, which was manufactured by Enercon, normally operates in Enercon mode 2,300 KW ("the 2300 mode"). The defendant trialled Enercon mode 1,600 KW (" the 1,600 mode") . This operation mode reduces the speed of the rotors at higher wind speeds, with the aim of lowering WTN levels which potentially reduces power output by up to 30%. The defendant collected noise monitoring data on foot of this trial ("the 2024 1,600 mode data"). It did not carry out any further monitoring of the WTN in the 2,300 mode, to provide a baseline for mitigation measures or to investigate the conditions under which adverse impact occurs. It did not implement a period of turbine shutdown to assess background noise levels.

9. The plaintiffs maintained that the 1,600 mode does not abate the nuisance. The defendant disagreed. Both remedy and quantum of damages therefore required to be determined in module 2. In respect of remedy, the defendant submitted at case-management hearings, that the plaintiffs ought to be confined to damages in lieu of an injunction ("damages in lieu"). If the court held for the defendant on this issue, then it would be necessary to assess damages for both past and future nuisance. The court was informed that, if it ordered damages in lieu, Ms. Webster intended to leave Hill House ("HH") and would then seek the costs of alternative accommodation ("the accommodation claim") as part of her claim to damages for future nuisance. Irrespective of the merits or de-merits of the accommodation claim, its adjudication would add to the duration and costs of the hearing of module 2. [5] On the other hand, the accommodation claim would not arise at all should the court decide to grant an injunction restraining future WTN nuisance (rather than confining the plaintiffs to damages in lieu for such future WTN nuisance). [6] I therefore determined that module 2 ought to be subdivided into two parts. The first part of module 2 would determine whether the plaintiffs ought to be confined to damages in lieu for future WTN nuisance or whether future WTN nuisance should be abated by injunction (and the precise terms of any such injunction). If the plaintiff were to be confined to damages in lieu, the second part of module 2 would then assess damages for both past and future WTN nuisance. If on the other hand, future WTN was to be restrained by injunction, then the second part of module 2 would assess damages for past WTN nuisance only.

10. Accordingly, the issues for determination in this judgment are whether the plaintiffs ought to be confined to damages in lieu or whether the nuisance should be abated by injunction and, in the latter instance, whether this court should order turbine shut down or some other form of restricted operation. The assessment of damages for WTN nuisance does not presently arise.

11. Because they maintain that the mitigation mode has not resulted in an abatement of the nuisance, the plaintiffs seek an order directing the shutdown of T2 during sensitive periods. The defendant's position is somewhat hard to discern. Its original argument, subject to its right to appeal, was that restricting T2 to the 1,600 mode during sensitive times fully abated the nuisance. Now, however, the defendant's principal argument is that the WTN does not pose a nuisance to the plaintiffs even in the 2,300 mode and that no mitigation is therefore required.

12. The defendant has always reserved its right to appeal this court's finding on liability in module 1. There is nothing controversial about this. Such appeal should, in accordance with established principles, proceed on the evidence presented to the court in the course of module 1.

13. However, rather than confining itself to the matters falling for determination in module 2, the defendant has sought to adduce new evidence on the issue of liability, to which the plaintiffs take objection. The defendant also argues that, on the basis of this new evidence, I should revisit my finding on liability made at module 1. The plaintiff resists the re-opening of the principal judgment.

14. As same is in dispute, it is first necessary to delineate the evidence which I will admit in module 2 and to decide whether this court will re-visit its principal judgment.

The delineation of the evidence for module 2

Background chronology

15. In preparation for module 2, the parties exchanged expert reports and statements of evidence. A substantial part of Mr. Carr's report and statement is devoted to demonstrating that, in the 2,300 mode, total operational noise levels [7] do not cause a nuisance to the plaintiffs and that there is no requirement for noise mitigation (save where the context otherwise requires, I will refer to this as "the disputed new evidence"). The parties' reports and statements were furnished to the court several weeks before the hearing of module 2. On considering same, I listed the matter for mention. I queried the basis upon which the defendant sought to adduce the disputed new evidence given that, subject to an argument that the plaintiffs should be confined to damages in lieu, module 2 was confined to determining what abatement measures ought to be ordered to obviate the WTN nuisance. I indicated that the court did not propose to have regard to evidence which did not pertain to these issues.

16. No application was made by the defendant for leave to adduce the disputed new evidence. Nor, prior to the hearing of module 2, was any application made by the plaintiffs to redact or exclude same. On day 1 of module 2, I requested legal submissions from the parties on the admissibility of the disputed new evidence. Unfortunately, neither party appeared ready to address this issue at that time. I therefore took up the evidence of Mr. Brazil, the director of the defendant company. In his direct evidence, Mr. Brazil referred to part of the disputed new evidence. Before commencing his cross examination, counsel for the plaintiffs applied to exclude the disputed new evidence. I directed the plaintiffs to identify the precise portions of Mr. Carr's report and statement to which they took objection and to notify same to the defendant overnight. I directed that, in the first instance, the parties should explore whether redaction of any portion of Mr. Carr's report and statement could be agreed.

17. When the matter resumed the next morning, the parties informed me that no agreement had been reached on redaction. I therefore proceeded to hear legal submissions on the admissibility of the disputed new evidence.

18. At the conclusion of the legal submissions, I ruled that certain portions of the disputed new evidence could not, on any conceivable basis, fall within the scope and rationale of the defendant's argument for admissibility. I therefore ordered the redaction of limited portions of Mr. Carr's report.

19. I determined that, in light of a particular argument advanced by counsel for the defendant (which I will explain at para. 55 et seq. below), it was necessary to hear expert evidence before reaching a conclusion on the admissibility of the bulk of the disputed new evidence. I therefore received Mr. Carr's report and statement (save for the limited portions already redacted) on a de bene esse basis and deferred my final ruling on admissibility to this judgment. I now set out this court's ruling on admissibility.

Nature of the disputed new evidence

20. In order to understand the court's ruling on admissibility, it is necessary to describe the disputed new evidence in some detail. It comprises Mr. Carr's new analysis of the raw noise monitoring data presented to the court by the plaintiffs in the course of module 1. The raw data consists of external audio recorded by Ms. Sarah Large in 2017 at Nettlefield, which was at that time owned by Mr. Shorten and Ms. Carty ("the 2017 NF data").

21. The defendant has now carried out what Mr. Carr terms an "AM assessment" of the 2017 NF data. An "AM assessment" can be explained as follows: older planning guidelines such as The Wind Energy Development Guidelines 2006, issued by the Department of the Environment, Heritage and Local Government in December, 2006 ("WEDG 2006"), make no express allowance for AM. However, in 2014, as the impact of AM came to be appreciated, the Institute of Acoustics ("the IOA") developed a method for measuring AM, the Reference Method ("the IOA RM"). [8] Although the IOA RM sets out the methodology for calculating AM values, it does not set a limit of acceptability for AM values, either for planning or for nuisance purposes. In 2016, a Report, commissioned by the Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy ("the Phase 2 Report") recommended that AM controls at the planning and development stage were best achieved by means of a suitable penalty scheme, whereby increasing levels of AM would attract a decibel penalty ("AM penalty"), which would be added to the relevant WTN levels for the purposes of fixing decibel limits and testing compliance therewith. The Phase 2 Report suggests the following AM penalties:

· For AM with a peak to trough level of less than 3dB: no AM penalty

· For AM with a peak to trough level of 3dB to 10dB: a sliding scale of AM penalties ranging from 3dB to 5dB

· For AM with a peak to trough of equal to or greater than 10dB: a 5dB AM penalty

22. The Phase 2 penalty scheme has not been adopted in either Great Britian or Ireland. However, the Draft Revised Wind Energy Development Guidelines, published by the Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage in December 2019 ("draft WEDG 2019") does utilise it. Although draft WEDG 2019 has since been withdrawn, the methodology it employs, as opposed to the detailed noise limits therein, is still instructive.

23. The disputed new evidence is a new analysis of the 2017 NF data consisting of the following steps:

2017 NF data: calculation of noise levels by windspeed

24. Mr. Carr analyses the raw data gathered by Ms. Large and tabulates total operational noise levels by windspeed.

2017 NF data: calculation of AM value in accordance with the IOA RM

25. Mr. Carr has measured AM values per windspeed in accordance with the IOA RM ("Carr's IOA RM analysis").

2017 NF data: calculation of AM penalty in accordance with the Phase 2 Report

26. Mr. Carr has calculated the applicable AM penalty per windspeed in accordance with the Phase 2 Report [9] and presented same on a series of spiderweb graphs. [10]

2017 NF data: add AM penalty to the calculated noise level per windspeed

27. Mr. Carr has calculated and tabulated total operational noise levels plus AM penalties ("the penalised noise level") per windspeed.

2017 NF data: comparison of the penalised noise level per windspeed with WEDG 2006

28. Mr. Carr has then compared the penalised noise level per windspeed with the fixed night time limit in WEDG 2006, which he contends is 43dB. [11]

2017 NF data: Mr. Carr's conclusions

29. Mr. Carr concludes that the penalised noise levels in the 2,300 mode are lower than the WEDG 2006 noise limit and that nuisance is thereby excluded. I will refer to this entire analysis as "the Carr comparative exercise". I should say that Mr. Carr has carried out precisely the same analysis of the WTN in the 1,600 mode and has reached a similar conclusion: the penalised noise levels in the 1,600 mode are lower than the WEDG 2006 noise limit and nuisance is thereby also excluded.

Legal principles regarding the admissibility of new evidence and the re-opening of a court's prior judgment

30. The defendant cites Greenwich Project Holdings Ltd v. Con Cronin [2021] IEHC 145 in which Hyland J. observed that where an application is made to revisit a judgment, the court must decide if there are strong reasons for so doing. The defendant argues that strong reasons exist in this case, and that, accordingly I should admit the disputed new evidence and revisit my finding on liability. In oral argument, counsel for the defendant invoked the following principles identified by Finlay C.J. in Murphy v. Minister for Defence [1991] 2 IR 161:

"1. The evidence sought to be adduced must have been in existence at the time of the trial and must have been such that it could not have been obtained with reasonable diligence for use at the trial;

2. The evidence must be such that if given it would probably have an important influence on the result of the case, though it need not be decisive;

3. The evidence must be such as is presumably to be believed or, in other words, it must be apparently credible, though it need not be incontrovertible."

31. These principles were developed in the context of the admission of new evidence on appeal. However, in Re McInerney Homes Ltd [2011] IEHC 25, Clarke J. (as he then was), applied them to a case in which judgment had been delivered, but final orders had yet to be made. Clarke J. held that the test for the admission of new evidence in such circumstances should be at least as exacting as the test applying at the appeal stage. This was approved by the Supreme Court on appeal [2011] IESC 31.

32. In Inland Fisheries Ireland v. O'Baoill [2015] IESC 45, the Supreme Court applied the above principles to an application to admit new evidence in a modular trial. Clarke J. acknowledged that, in a modular trial, no formal issue of res judicata arises out of the findings of an earlier module. Nevertheless, formal findings of the court on a specific issue determined in an earlier module should only be reopened in exceptional circumstances. It would defeat the purpose of a modular trial if a party could easily and for little good reason, seek to reopen matters already determined, when the court came to consider later modules. Whilst the court has room for manoeuvre to do justice between the parties, it should not, without good and strong reason, enable any finding to be revisited in a subsequent module. In essence therefore, a modular trial remains in being until all modules are concluded and there is no formal jurisdictional barrier to allowing new evidence in to reopen a point already decided. However, this is a jurisdiction to be exercised sparingly.

33. Costello J. (as she then was) also considered when it might be appropriate to admit new materials to re-open a judgment in Hinde v. Pentire Property Finance Designated Activity Company & Kavanagh [2018] IEHC 575. [12] Costello J. observed that the test to re-open a judgment contains two elements, namely:

· The new materials would probably have an important influence on the result of the case and be credible.

· Such new evidence will not ordinarily be permitted to be relied on, if it could, with reasonable diligence, have been put before the trial court.

34. More recently, in Bailey v. Commissioner of An Garda Siochana [2018] IECA 63, the Court of Appeal confirmed that a court of first instance has jurisdiction to revisit an issue decided in a written judgment. The test is whether the court is satisfied that there are " exceptional circumstances" or "strong reasons", which warrant it doing so.

Application of legal principles in relation to the admissibility of new evidence

35. The parties' oral legal submissions focussed primarily on Murphy criterion 1, whether the evidence sought to be adduced could with reasonable diligence have been obtained for use at the trial.

36. During the course of module 1, both Ms. Large and Mr. Stigwood gave extensive direct evidence presenting and commenting upon, inter alia, the 2017 NF data. A substantial number of graphs derived from this data were placed before the court in reports by Ms. Large, running to 150 pages. Ms. Large also gave oral evidence in relation to the features of the WTN appearing on these graphs. In addition, audio recordings taken from the 2017 NF data were played to the court by Mr. Stigwood (along with audio recordings of other data), who also provided his professional opinion in relation to the features of the WTN. Both Ms. Large and Mr. Stigwood were subject to lengthy cross examination.

37. Having considered the expert reports, the audio recordings, the evidence emerging from the direct and cross examination of Ms. Large, Mr. Stigwood, Mr. Carr and Mr. O'Reilly, together with all of the factual evidence in the case, the court accepted Ms. Large's opinion (and much of Mr. Stigwood's opinion) as to the intrusive features of the WTN and delivered judgment on that basis. The defendant may not belatedly challenge the evidence and opinion of Ms. Large (and Mr. Stigwood) by ex post facto analysis of the data she presented.

38. The 2017 NF data was furnished to the defendant in advance of the trial of module 1. It had every opportunity to comment upon this data, to advance a contrary analysis thereof and to challenge the opinions of the plaintiffs' experts in relation thereto. Further, although the defendant had ample opportunity to conduct the IOA RM analysis of the 2017 NF data now sought to be adduced, it carried out no analysis of its own of this data for the purposes of module 1. Indeed, I was extremely surprised that it did not do so. The defendant also had every opportunity to subject the 2017 NF data to the Carr comparative exercise now sought to be adduced. Furthermore, the defendant elected not to perform an IOA RM analysis on any of the data gathered by its own expert in Module 1, Mr. O'Reilly.

39. On this basis it could not possibly be said that the disputed new evidence "could not have been obtained with reasonable diligence for use at the trial?"

Does the new technical specification published by the International Electrotechnical Commission provide a justification for the introduction of the disputed new evidence?

Justification advanced in Mr. Carr's report

40. It is common case that the defendant could have put an IOA RM assessment of either the 2017 NF data or its own data before the court at module 1. Permitting the introduction of new evidence at module 2 simply because the relevant matters were not advanced at module 1 would be a recipe for procedural chaos. In apparent reply to this objection, Mr. Carr's report cites para. 375 of the principal judgment as follows:

"I should say that this court would place very considerable weight upon up-to-date, scientifically robust planning guidelines on wind energy developments which advised on the particular decibel level at which WTN, when combined with AM of a particular nature, is considered an acceptable interference with amenity. If responsive to the particular aspect of the noise complained of, such guidance would be highly persuasive in a nuisance action. A plaintiff who sought to argue that such guidance did not represent a reliable - if not a wholly reliable - indicator of what is objectively reasonable would, in my view, bear a heavy onus. However, no such guidance currently exists; planning guidance in this jurisdiction (and elsewhere) can fairly be described as flux and cannot identify the line of acceptability."

41. Mr. Carr's report states since the date of the principal judgment, an important new IEC technical specification has been published (IECTS 61400-11-2:2024, acoustic noise measurement techniques, measurement of wind turbine sound characteristics in receptor position) ("the IEC"). The defendant argues that the IEC was not in existence and could not have been obtained with reasonable diligence for the use at the trial. Essentially, therefore, the defendant argues that the IEC is new evidence emerging since the trial and, further, that it meets the lacuna identified in para. 375 of the principal judgment. I will take these points in reverse order.

The IEC does not meet the lacuna identified in para. 375

42. The IEC does not constitute "scientifically robust planning guidelines on wind energy developments which [advise] on the particular decibel level at which WTN, when combined with AM of a particular nature, is considered an acceptable interference with amenity" in the sense contemplated by para. 375 of the principal judgment.

43. The IEC does not dictate or even recommend any regulatory metrics. Rather, it provides guidance on how best to isolate WTN for comparison with local regulation. It also provides guidance for the quantification of the impact of the sound characteristics of the WTN, such as AM values, again for comparison with local regulation. The IEC does not delineate what level of noise or what AM values are acceptable in terms of interference with amenity. The proposition that the IEC is responsive to the lacunae identified at para. 375 is entirely erroneous.

The IEC is not the disputed new evidence

44. It is well established that where the new evidence tendered is in respect of matters occurring after the judgment from which an appeal is brought, no special leave is required. If the evidence was not in fact "in existence at the time of the trial", then the failure to adduce it is not attributable to any omission on the part of the party seeking to introduce it. The power of the court to receive such evidence is discretionary. The interests of justice may require its admission, particularly if it would have an important influence on the result of the case.

45. In the present case, however, this does not assist the defendant. Although the IEC post-dates the principal judgment, the disputed new evidence sought to be adduced is not the IEC per se. The disputed new evidence is Mr. Carr's IOA RM analysis of the 2017 NF data and his ensuing comparative exercise. The IEC is merely the vehicle through which the defendant seeks to introduce this evidence.

46. The fact that the IEC had not been published prior to the hearing of module 1 cannot reasonably justify or explain the defendant's failure to carry out, and to tender to the court, an IOA RM analysis and the ensuing comparative exercise at that time. The IEC cannot justify the defendant's 13th hour attempt, after judgment has been handed down against it, to attempt to plug this very obvious lacuna in its proofs.

47. In order to link the disputed new evidence to the IEC, Mr. Carr explains that the IEC "implements" the IOA RM "for quantifying AM". He observes that the IEC identifies the IOA RM as the chosen AM assessment method. The argument appears to be that the IEC represents best practice in the measurement and assessment of WTN and that its endorsement of the IOA RM is a new development legitimising the late admission of the disputed new evidence.

48. However, endorsement of the IOA RM is nothing new. As observed in the principal judgment, draft WEDG 2019 also identified the IOA RM as the most robust methodology for measuring AM, as did the ETSU Review of 2023. In the principal judgment, I fully accepted that the IOA RM was a robust methodology. [13] The further endorsement of the IOA RM by the IEC neither explains why the IOA RM analysis of the 2017 NF data was not presented at module 1, nor justifies its admission now.

49. Mr. Carr emphasises that the IEC is specific to WTN. However, this is irrelevant as the IOA RM was also WTN specific. He also points out that the IEC defines AM as including both swish and thump AM. This was also the case in respect of IOA RM. There is little new here to justify the admission of the disputed new evidence.

50. Despite suggestions to the contrary in legal argument and in aspects of Mr. Carr's oral evidence, the IEC is not an international standard. It is a technical specification. Para. 3.1.5 of the 'ISO/IEC Directives, Part 2', Principles and rules for the structure and drafting of ISO and IEC documents (9th edn, 2021), defines a technical specification as being one in respect of which there is a future possibility of agreement on an international standard but for which at present:

· the required support for approval as an international standard cannot be obtained,

· there is doubt on whether consensus can be achieved,

· the subject matter is still under technical development, or

· there is another reason precluding immediate publication as an international standard.

51. Mr. Stigwood also gave evidence that the IEC has not yet been adopted by the relevant Irish or European authorities. No evidence to the contrary was presented by the defendant.

52. Furthermore, the relevant sections of the IEC dealing with the assessment of AM are said to be "informative", rather than "normative". Whilst a normative element of a document provides rules or guidelines, an informative element is merely intended to assist the understanding or the use of the document or to provide contextual information about its content, background or relationship with other documents. This also undermines the weight to be attached to this aspect of the IEC.

53. The IEC is not therefore a transformative piece of evidence sweeping away the defendant's omission to present the disputed new evidence. The position is all the more stark in light of the defendant's trenchant criticism at module 1 of Mr. Stigwood's failure to carry out a formal IOA RM assessment. Despite contending that the IOA RM was a robust methodology, and indeed that it was the exclusive methodology for assessing WTN AM, [14] the defendant did not carry out such an analysis. As it would stretch credulity to suggest that it had not occurred to the defendant to do so, its failure to carry out (or if carried out, to present) an IOA RM analysis at module 1, can only be seen as a deliberate decision.

54. In short, the report of Mr. Carr and its accompanying statement reveal no argument that the IOA analysis of the 2017 NF data (and the entire Carr comparative exercise) could not, with reasonable diligence have been adduced at module 1.

Alternative justification advanced by the defendant in oral legal submissions: substantial differences between the IOA RM analysis and the IEC AM analysis

55. In legal argument on day 2, the defendant introduced the concept of separate and defined IEC analysis of AM ("IEC AM analysis"). Counsel argued forcefully that there are material and substantial differences between the IOA RM analysis and the IEC AM analysis. When compared with the IOA RM analysis, the IEC AM analysis was "a different standard that reaches a different result", such that Mr. Carr's IEC AM analysis is in fact new evidence that could not with reasonable diligence have been adduced at module 1. [15]

56. This was a surprising submission because Mr. Carr's report and statement did not refer to any significant or material differences between the two methodologies and their results. On the contrary, Mr. Carr's written evidence depicts the IEC as endorsing the IOA RM.

57. The nature and relevance of the apparent distinction between the IOA RM and IEC AM methodologies (and their results) appeared to me to be highly technical. In legal argument, counsel frankly conceded that he did not fully understand it. As such, I was persuaded that I could not rule on admissibility on the basis of legal argument alone. I therefore decided to receive the disputed evidence de benne esse so I could hear expert evidence before ruling on the admissibility of the disputed new evidence.

58. When Mr. Carr came to give evidence it became apparent that any difference between the two methodologies could not possibly justify the admission of the disputed new evidence. Mr. Carr explained that for technical reasons which it is not necessary to detail here, the IOA RM has the capacity to miss low frequency AM, and that this issue had been remedied in the IEC AM assessment methodology. [16] [17]

59. This potential under-estimation of low frequency AM neither explains nor justifies the defendant's failure to present an IOA RM analysis at module 1. Indeed, such rationale is entirely contrary to the defendant's committed position throughout module 1. This was that the IOA RM analysis was not just a reliable methodology to assess AM, including thump AM, but that it was the only acceptable methodology. The defendant offered no qualification to its support of the IOA RM and never allowed for the possibility that it could miss thump AM. Nor, as I recall, did the plaintiffs' experts dwell on this issue; and I did not refer to it at all in reaching my findings at module 1.

60. In addition, far from producing materially different results, Mr. Carr's evidence at module 2 was that one could expect the results of the two assessments to be broadly similar, albeit that the IEC AM assessment was "more conservative" than the IOA RM, because it took full account of thump AM.

61. Therefore, whilst I accept that there are some differences between the IOA RM and the IEC AM analysis, these are not of particular relevance to the issues that were before the court in module 1 (or indeed those arising in the present module) and in no way explain the defendant's failure to perform and present an IOA RM analysis at the appropriate time.

Conclusion on criterion 1 of Murphy v. Minister for Defence

62. With any diligence, the disputed new evidence could have been adduced at module 1. I am driven to conclude that the defendant has seized upon the IEC as a contrivance to, as it sees it, mend its hand. The IEC does not set a new standard for nuisance. It is a measurement methodology which is still in development. It has not yet been adopted in Ireland. The IOA RM analysis and the IEC AM analysis are not substantially different. Any distinctions between the two are of no real relevance to the issues arising in this case. The IEC cannot possibly justify the defendant in now presenting an analysis of data that was furnished to it in 2022.

63. As O'Donnell J. (as he then was) observed in Emerald Meats v. Minister for Agriculture [2012] IESC 48, a trial is not a laboratory experiment where one element can be substituted, all other elements maintained and a different outcome obtained. There are very few cases in which the losing side does not regret that different witnesses were not called, different evidence given or different points made in cross examination or submission. There are few cases which in hindsight could not be rerun with different witnesses, evidence, arguments or advocates. But to consider that such a course is in the interests of justice is to engage in the delusion that endless litigation is a desirable, rather than a tormented state. The court has made its decision on the evidence advanced over 51 days. The defendant may reasonably dispute the merits of this court's conclusion; but it cannot doubt that it is the conclusion. In short, the Murphy criteria do not permit the admission of the disputed new evidence.

Is the disputed new evidence admissible qua baseline assessment?

64. The defendant also submits that the purpose of collecting the disputed new evidence was not to challenge this court's findings at module 1, but to establish a baseline to guide potential mitigation strategies.

65. I fully accept that a mitigation strategy is best devised on foot of complete and reliable baseline data. However, if the defendant had wished to carry out a baseline assessment then it should have gathered data directed to that purpose, rather than re-interring the plaintiffs' 2017 NF data.

66. I am not satisfied, as a matter of fact, that the IOA RM analysis (and the ensuing Carr comparative exercise) was a bone fide baseline assessment. The defendant's evidence on this issue is inconsistent. In closing argument, counsel for the plaintiffs directed the court to evidence suggesting that the defendant only analysed the 2017 NF data after the 1,600 mode mitigation trial had been completed. The defendant did not reply at all to this aspect of the plaintiffs' closing submissions.

67. If the disputed new evidence was, as the defendant contends, gathered to guide the mitigation trial, then why did it not inform that mitigation? Surely a mitigation programme guided by the disputed new evidence would have focussed on reducing noise levels at windspeeds associated with the highest AM values. Yet the defendant designed a mitigation programme which did precisely the opposite; the 1,600 mode produces no reduction whatsoever in WTN at the windspeeds when AM values are highest.

68. More importantly, the disputed new evidence does not comprise a useful or complete baseline assessment. As it presents only total operational noise, it does not actually inform one on WTN levels. The disputed new evidence does not include an assessment of background noise levels in what is clearly a very quiet and sheltered rural area. It does not assist on the question of whether this is a "low noise environment" within the meaning of WEDG 2006. [18] No data or analysis whatsoever is presented on the important issues of emergence of the WTN over background noise or low frequency noise/thump AM (even though the IEC treats of both). As will become apparent, the lack of evidence on background wind noise levels and its efficacy in masking WTN at different windspeeds is a critical omission. The disputed new evidence does not even present AM values in the manner required by either the IOA RM or the IEC. Instead of presenting AM values, it rather presents AM penalties only.

69. A "baseline" is a starting point to be used for comparison. It will only be of value if it comprehensively presents the relevant data points. Here, the defendant has cherry-picked from the IEC and has presented only one suite of data (AM penalties and total operational noise levels), whilst omitting other important data, which one would expect in any valid baseline study.

70. Furthermore, whilst the disputed new evidence does present AM penalties in the 2,300 mode at a range of wind directions and windspeeds, the same information can be gleaned from the 2024 1,600 mode data. This is because it is common case that the turbine's operational mode does not alter AM values. Nor does the operational mode impact upon spectral frequency, thump AM, erraticism or impulsivity. [19] Therefore, any findings of fact that I may make in relation to these WTN characteristics in relation to the 1,600 mode apply equally to the 2,300 mode. Analysis of the 2017 NF data does not assist one's understanding of these features of the WTN.

71. I conclude that the evidence already put before the court at module 1, the 2024 1,600 mode data and the totality of the other evidence from module 2, are sufficient for the court to determine the issues at hand. I therefore decline to admit the disputed new evidence and will admit Mr. Carr's report and statement and Mr. Brazil's statement in redacted form only. Essentially whilst I admit the data pertaining to the 2024 1,600 mode, I exclude the 2017 NF data.

72. However, lest I am wrong in any of my above analysis, I will now explain for completeness why the disputed new evidence (if admitted) would not have an important influence on the result of the case. In other words, even if admitted the disputed new evidence would not substantially impact or alter my findings on liability at module 1.

The disputed new evidence would not substantially impact or alter my finding on liability

The IOA RM analysis of the 2017 NF data supports, rather than undermines this court's finding on AM values in the principal judgment

73. The IOA RM analysis of the 2017 NF data, which I have decided to exclude supports, rather than undermines, this court's finding of regular and sustained periods of typical AM values at a level widely acknowledged to be associated with high levels of annoyance. This finding in the principal judgment had three components.

74. As a first component, I accepted Ms. Large's evidence that on foot of her 2017 monitoring, AM values significantly in excess of 5 dB are a substantial feature of the WTN. I found that the time-domain graphs revealed a common thread of AM values in excess of 5 or 6 dB and that they also showed that AM values of 10 dB are frequently present, both externally and internally. Indeed, this was not disputed by the defendant. Although the disputed new evidence does not comply with the IEC reporting requirements for AM assessment, it is nonetheless common case that at night in the downwind direction average AM values at windspeeds between 4m/s and 8m/s are between 6.5 and 10dB. Clearly, there will be periods when AM values are lower than this. However, there will also be periods when AM values are higher. Indeed, the prevalence of AM average penalty points of 4-5 dB on the spiderweb graphs, demonstrates that AM values of 10 dB occur regularly .

75. As a second component, I accepted Ms. Large's evidence that AM values of 5 dB and above, if audible at a sufficient level are capable of amounting to an unreasonable impact. This finding is in no way impacted by the disputed new evidence.

76. As a third component, this court's findings of fact that the WTN AM was "audible at a sufficient level" was based, inter alia, on its own experience of the audio recordings. I found that on the majority of the audio recordings, both internal and external, the WTN is the only noise that one can consistently identify. Its nature is such that it constantly draws one's attention and it was not masked by other ambient noise. This finding of fact was also based on the oral evidence of the plaintiffs themselves in relation to their experience of the WTN and on the direct evidence of their experts, none of which was undermined in cross examination. I fail to see how the disputed new evidence should incline this court to revisit any of this. In short, the evidence sought to be admitted would not have an important influence on the court's findings as to the nature and impact of the AM values.

The disputed new evidence does not undermine this court's finding on low frequency noise and thump AM

77. The principal judgment finds that there is a significant audible lower frequency component to the WTN. This is both heard and felt as a vibration or sense of pressure. This also manifests as thump AM which I found was the "most intrusive" element of the WTN. This finding was based on the audio recordings, the evidence of the plaintiffs and the expert evidence of Ms. Large in particular (which in this respect was essentially uncontradicted by Mr. Carr's testimony).

78. The disputed new evidence does not even address, still less undermine this finding. The defendant carried out no analysis of low frequency sound at module 1. This remains the position.

79. It is common case, that neither the IOA RM nor the IEC AM analysis differentiate between swish and thump AM. Although thump AM is widely acknowledged to be more annoying and intrusive than swish AM, these methodologies assign the same value to both forms of AM. This may be a perfectly good starting point from a regulatory perspective but it does not provide a complete answer to a nuisance claim in which thump AM is the most intrusive element.

The disputed new evidence does not undermine this court's finding on dominance

80. Para. 510 of the principal judgment, concludes that the dominance of the WTN is most likely due to a combination of high AM values, low frequency AM, the emergence of the WTN over low background noise levels ("emergence") and to its other intrusive features such as erraticism, impulsivity, unpredictability, etc. At module 1, the defendant declined to carry out or present any reliable analysis of background noise levels, emergence or of the other intrusive features just discussed. That omission persists.

The defendant's reliance on a combination of WEDG 2006, the IEC and the Phase 2 penalty scheme is misplaced

81. The defendant's "Eureka moment" is that the Carr comparative exercise shows that penalised noise levels in the 2,300 mode do not exceed "the 43dB limit level in the WEDG 2006". This is said to foreclose WTN nuisance in the 2,300 mode (and a fortiori in the 1,600 mode).

82. To develop this a little further, the defendant points to several passages in the principal judgment. These are to the effect that WEDG 2006 is not the determinant of nuisance because it is not a yardstick, objective or otherwise, against which to assess what particular AM values or what particular degree of thump AM is objectively reasonable. The defendant argues that the Carr comparative exercise now accounts for these deficits in WEDG 2006, because it penalises AM values. The Carr comparative exercise is said to supply the missing yardstick.

83. There are, to put it mildly, difficulties with this approach.

Argument inconsistent with the defendant's position at module 1

84. First the argument that such comparative exercise is the determinant of nuisance, is entirely inconsistent with the case presented by the defendant at module 1, which was that the 2004 planning permission was a wholly reliable indicator of what was objectively reasonable at this locality.

Lacuna: WEDG 2006 does not address thump AM

85. Second, even within its own four corners, the Carr comparative exercise contains a serious lacuna. It addresses only one of the two omissions just discussed. It addresses only the failure of WEDG 2006 to account for AM values. It does not address the second omission, the failure to take account of the added intrusion of thump AM.

WEDG 2006 was not drafted with nuisance in mind

86. Third, the principal judgment does not state that were it not for these two specific omissions, the WEDG 2006 noise limits (with which, for the sake of argument, the principal judgment accepted the WTN complied), would be the determinant of nuisance. WEDG 2006 was not drafted with nuisance in mind.

WEDG 2006 was not drafted with AM in mind

87. Fourth, WEDG 2006 was also not drafted with AM in mind. The IOA RM and Phase 2 Reports, postdate WEDG 2006 by a decade. The IEC, upon which the defendant now places reliance, postdates WEDG 2006 by almost two decades. There is no logic in bolting penalties for AM developed 10 to 20 years later onto the noise limits set out in WEDG 2006. Indeed, this is clear from the IEC itself, which states that any adjustments to noise limits "are typically defined in local regulation" (emphasis added). WEDG 2006 does not define, or even contemplate, adjustments to noise limits by reference to AM values. WEDG 2006 is an entirely different methodology. WEDG 2006 is a round hole into which the defendant seeks to force a square peg, the Phase 2 penalties scheme.

WEDG 2006 is under review and takes no account of low frequency WTN

88. Fifth, if the Phase 2 penalty scheme is to be bolted on to any methodology as the determinant of nuisance, then why logically should that methodology be WEDG 2006? The defendant's answer to this question appears to be: WEDG 2006 is still relied upon in the planning and development of windfarms. I accept that s. 28 of the Planning and Development Act 2000 continues to require planning authorities and An Bord Pleanála to have regard to ministerial guidelines such as WEDG 2006. However, that does not imbue WEDG 2006 with talismanic significance for the purposes of a nuisance assessment.

89. WEDG 2006 is currently under review. There is evidently a range of potential methodologies that the Government might adopt to replace it for planning and development purposes. There is no reason to assume that new Guidelines will ape the "flat" night time noise limit of 43 dB (whether including AM penalties or not). Still less can one assume that new Guidelines will apply this noise limit irrespective of the frequency of the WTN or of background noise levels. Indeed, I would have thought that this is unlikely.

90. There is therefore no reason why this court should accept that a "flat" night time noise limit of 43 dB (whether including AM penalties or not) is the determinant of nuisance. The principal judgment observes that the current direction of travel in wind energy planning guidance ("the modern planning approach") is towards setting decibel limits, combined with a penalty for character such as AM. I accept that the Carr comparative exercise, which combines WTN levels and AM penalties, reflects this aspect of the modern planning approach. However, the principal judgment goes on to observe that the modern planning approach incorporates limits on low frequency noise. For example, unlike WEDG 2006, draft WEDG 2019 limits low frequency noise. This important criterion is absent from the Carr comparative exercise.

WEDG 2006 takes no account of night time background noise levels

91. Sixth, the modern planning approach in publications such as draft WEDG 2019, is to take background noise levels into account in setting WTN limits. Draft WEDG 2019, notes that the principle of a 5 dB emergence has been regarded as good practice for many years.

92. WEDG 2006 appears to consider that WTN should assessed by reference to background noise levels. It provides:

"Noise impact should be assessed by reference to the nature and character of noise sensitive locations.... Noise limits...should reflect the variation in both turbine source noise and background noise with wind speed."

93. Ultimately, however WEDG 2006 appears to allow the planning authority to select a higher WTN day time noise limit of up to 45dB if considered appropriate [20] (save in "low noise environments"). It also imposes a "flat" 43dB noise limit at night, regardless of background noise levels.

94. By contrast, draft WEDG 2019 generally limited WTN to 5 dB above background noise levels at night time as well as during the day time (irrespective of whether the windfarm is in a low noise environment). In a typical quiet rural site this would tend to limit night time WTN to levels below 43 dB for low to moderate windspeeds. However, this modern planning approach is not reflected in the defendant's comparative exercise.

95. In short, the Carr comparative exercise translates AM values into an estimated decibel level for regulatory purposes but ignores all other important characteristics of the WTN such as low frequency noise, emergence over background noise and the time of occurrence of the AM. I am not convinced that such a methodology remotely accords with the modern planning approach or with best practice in the assessment of WTN nuisance.

S. 28 is not the yardstick of nuisance

96. Seventh, the defendant relies on Nagle v. An Bord Pleanála [2024] IEHC 603 ("Nagle") as endorsing WEDG 2006 for all purposes, including nuisance assessment. I cannot see how Nagle greatly assists the defendant. It is true that Humphreys J. held that WEDG 2006 remains the relevant ministerial guideline for the purposes of s. 28. However, he also stated in the course of his judgment [21] at paras. 99-101, that a planning permission granted in accordance with WEDG 2006 would not be immune to a nuisance action by virtue of that fact.

97. I agree with Humphreys J., Planning guidelines, such as WEDG 2006 (and individual planning permissions) predict that, as regulated, WTN will not be an unwarranted intrusion on amenity. However, that prediction may transpire to be incorrect in a given location. This may be because the WTN displays unanticipated characteristics such as substantial low frequency noise or thump AM. It may be because low background noise at a sheltered location such as this has not been fully considered in the noise limits set. The WTN nuisance in this case is attributable to a combination of factors, only some of which have been assessed by the comparative exercise now undertaken by the defendant. Although I repeat that a plaintiff who asserts nuisance will bear a heavy burden if the WTN is in accordance with up to date and robust planning guidelines, which are responsive to the relevant WTN characteristics complained of, none presently exist, and the Carr comparative exercise is a world away from meeting that lacuna.

WEDG 2006 does not address most of the Defra criteria

98. Eighth, the defendant argues that because neither this court nor the plaintiffs have identified a specific WTN decibel limit (whether combined with AM penalties or otherwise) as marking the boundary of nuisance, it had "no option" but to devise a comparative exercise which applies the "flat" night time limit of 43 dB set out in WEDG 2006.

99. As stated in the principal judgment a robust assessment of a WTN nuisance complaint cannot be conducted without reference to factors such as those discussed in the Defra methodology. [22] In all its evidence in the course of module 1, the defendant addressed only three of the ten criteria derived from Defra ("the Defra criteria") [23]: the level of WTN, the time of day or night when the WTN occurs and, to a limited extent, the sensitivity of the complainant. The disputed new evidence partially addresses one of the ten Defra criteria, the "type of noise", by presenting average AM penalties. However, this evidence does not address other important aspects of the noise "type" such as variability, regularity and predictability of the noise. Further, the defendant has not considered at all the following seven important Defra criteria: whether any aggravating characteristics are present in the WTN (the spectral content of the WTN and whether thump AM is present); the characteristics of the neighbourhood where the WTN occurs; the exceedance of WTN over background noise; the impact of the WTN on basic needs such as sleep; how easily the WTN can be avoided; what measures could reduce or modify the WTN; and finally the duration and how often the WTN occurs.

The Phase 2 penalty scheme is under review

100. Ninth, Mr. Stigwood's uncontradicted evidence at module 2 is that the Phase 2 penalty scheme, which is an essential component of the Carr comparative analysis, is currently under review. In particular, consideration is being given to injecting an element to reflect modulation frequency -in the sense of the rapidity-of the AM. This could be relevant at higher speeds of rotation when AM values are lower but when AM is likely to occur with greater frequency. Mr. Carr himself drew the court's attention to clause 4.5.30 of the Phase 2 Report which includes the statement that "This method is by necessity an interim recommendation based on the available evidence to date..." Insofar, therefore, as the defendant relies upon the Phase 2 penalty scheme, it is under review, which lessens its evidential weight.

The IEC does not apply the Phase 2 penalty scheme

101. Tenth, the IEC itself does not, as the defendant suggests, propose that the Phase 2 penalty scheme is applied to the local regulatory limit (in this instance, WEDG 2006). The Phase 2 penalty scheme is only an example of a potential local penalty scheme. Therefore, the importance attached by the defendant to the Phase 2 penalty scheme is not, on greater scrutiny, borne out.

Plaintiffs' further argument: the Carr comparative exercise misapplies the Phase 2 penalty scheme

102. I will finally deal with a "fall back" argument advanced by the plaintiffs' acoustic expert Mr. Stigwood. He argues that the defendant has misapplied the Phase 2 penalty scheme. This would mean that, even if I had admitted the disputed new evidence, it does not in fact show that the penalised WTN levels are lower than the WEDG 2006 noise limit.

103. To explain, Mr. Carr's comparative exercise purports to calculate penalties under the Phase 2 penalty scheme and then compare the penalised noise to the 43 dB "flat" night time limit under WEDG 2006. Mr. Stigwood observes that the Phase 2 penalty scheme fundamentally differs to WEDG 2006 in its approach to night time noise limits. This is particularly relevant in low noise environments. In low noise environments, WEDG 2006 limits day time noise to 35-40 dB. However, this lower limit is not translated across to night time limits, which are set at a "flat" 43 dB, irrespective of background noise levels. In a low noise environment, therefore the WEDG 2006 night time limit is higher than the WEDG day time limit.

104. By contrast the Phase 2 Report recognises that noise limits which are generally higher at night time than during the day, "raise the question about whether...noise limits... which are generally higher at night, accord with current Government policies to avoid, significant adverse noise impacts, and mitigate or minimise adverse impacts." . Therefore, if day time noise limits are lower than night time limits, the Phase 2 penalty scheme effectively applies the lower day time noise limit at night by the application of additional penalties.

105. Mr. Stigwood's opinion has always been that, absent the WTN, Ballyduff is a low noise environment and that the WEDG 2006 day time noise limit is 35-40 dB. As the WEDG 2006 night time noise limit of 43 dB is higher than this, the Phase 2 penalty scheme would apply the lower of these two limits at night. On this methodology, the WTN would exceed the relevant night time noise limit.

106. The defendant does not dispute that, correctly interpreted, the Phase 2 penalty report imposes an additional penalty "if, and only if, the numerical limit for night-time is set higher than that for daytime". However, it argues that this does not result in any change to the night-time noise limit in this case. This is because the defendant contends that Ballyduff is not a low noise environment. As such the night-time limit of 43 dB is lower, not higher, than the daytime limit of 45 dB and no additional penalties apply.

107. The defendant asserts that the court concluded that Ballyduff was not a low noise environment in the principal judgment. This is incorrect. Background noise levels were a live issue in module 1, which I considered at paras. 512-528 in particular. At para. 512, I expressly noted that the absence of background noise data meant that I could not assess whether this is a low noise environment within the meaning of WEDG 2006. Therefore, as the plaintiffs contended that nuisance arose inter alia by virtue of the fact that Ballyduff was a low noise environment, and thus bore the burden of proof on that issue, I held that I could not be so satisfied on the balance of probabilities.

108. For the purposes of module 1, I therefore assumed for the sake of argument that Ballyduff was not a low noise environment. [24] I accepted arguendo that the WEDG 2006 day time limit was up to 45 dB and that the night time limit was 43dB. On that assumption, I was satisfied that the noise limits in the planning permission and the WTN itself, were in accordance with WEDG 2006. The key point however, was that compliance with the WEDG 2006 limits did not delineate the parameters of WTN nuisance in this particular case. Irrespective therefore of whether or not Ballyduff was a low noise environment, compliance with WEDG 2006 was not determinative.

109. In summary, whether or not Ballyduff was a low noise environment was a live issue at module 1 which I did not have to decide, but which I assumed arguendo would fall in the defendant's favour. In doing so, however, I emphasised that there was no compelling evidence which would permit me to make a finding one way or the other on the issue. This remains the case.

110. At module 1, I determined that the onus of demonstrating nuisance remained at all times on the plaintiff. However, the onus of proof in substantiating its positive defence, which at that time was that the WTN complied with its planning permission, was on the defendant. We are now at a different stage of the litigation at which the defendant must surely substantiate its positive defence, which is now that on the application of the Phase 2 penalty scheme, the WTN complies with the relevant WEDG 2006 night time limit. I am satisfied the Phase 2 penalty scheme, properly interpreted, applies higher night time penalties to low noise environments. A strong argument can therefore be made that the onus of proof on this issue is now reversed and that the defendant bears the burden of proving that Ballyduff is not a low noise environment. Indeed, this would be entirely logical as only the defendant can reliably assess background noise levels which requires turbine shut down. As the defendant has not even attempted to investigate background noise, it is hard to see how this burden could have been discharged. This would tend to suggest that the defendant has not discharged the burden placed upon it of demonstrating compliance with the Phase 2 Report/WEDG 2006 night time noise limits, as properly interpreted.

111. Having said that, I accept that the defendant's argument that low background noise was not a live issue in module 2. It was not addressed in module 2 in either parties' expert reports. The argument arises from a single observation in Mr. Stigwood's oral evidence, which I accept the defendant did not anticipate. Although I afforded the defendant an opportunity to recall Mr. Carr to deal with this issue, I accept that by that stage, it was far too late for either side to present background noise data to the court. The low background noise issue remains incompletely explored in evidence and undetermined by the court. In these unusual circumstances, irrespective of the onus of proof, I am persuaded that it would be unfair to the defendant to hold against it on this specific point.

112. I will therefore decline to place any reliance on Mr. Stigwood's low noise environment argument. It is, in any event, entirely unnecessary to do so. Even if one fully ignores this argument, the analysis outlined at paras. 73 to 101 above admits of only one conclusion: even if I had admitted the disputed new evidence, this would not disturb this court's finding on liability in module 1.

Conclusion in relation to the disputed new evidence and in relation to the application to re-visit the principal judgment.

113. The defendant's written legal submissions cite the Supreme Court decision in Re McInerney Homes Ltd. in which O'Donnell J. (as he then was) expressed the view that the jurisdiction to reopen a judgment arises where a trial judge has proceeded on the basis of a particular assumption of fact which has transpired to be incorrect. In such circumstances, it could be said that the hearing, and indeed the judgment, had proceeded almost on the basis of a common mistake and that justice requires that the matter should be reconsidered. The defendant submits that there is "strong reason to re-visit the judgment" because new evidence has come to light (in the form of the IEC AM analysis of the 2017 NF data) which establishes that T2 is operating below the threshold set out in WEDG 2006.

114. However, this demonstrates no incorrect assumption of fact or common mistake in the hearing of module 1 or in the principal judgment. In the principal judgment, I assumed arguendo that the WTN noise levels did comply with the WEDG 2006 noise limits, but nonetheless found as a fact that WTN nuisance was proven on the evidence.

115. At para. 31 of their submissions, the plaintiffs state:

"What the Defendant says provides the full answer to the Plaintiffs' complaints and the test of acceptability for nuisance in Ireland is an unadopted measurement methodology linked to a proposed 2016 UK penalty scheme (itself apparently under revision) judged against an averaged overall decibel limit in a 2006 planning guidance."

116. I cannot disagree with that characterisation. In G v. A Judge of the District Court [2023] IEHC 386 [25] Simons J. noted that a judge asked to review their own judgment should have regard to the fact that, on most occasions, the appropriate avenue of redress for a person aggrieved by a judgment is to exercise their right of appeal. The parties to litigation are entitled to assume that, absent an appeal, a written judgment which has been approved by the judge and has been published, is conclusive. In the present case, the defendant has provided no credible basis for the court to exercise its rare and exceptional jurisdiction to revisit its prior judgment. Regrettably, the defendant's approach has served only to add an additional layer of delay, costs and judicial decision making to already protracted proceedings.

117. I will now turn to the proper business of module 2: the assessment of the mitigation measures trialled by the defendant and the appropriate remedy.

118. I will first set out the evidence of the parties. Although the defendant's witnesses gave evidence before the plaintiffs' witnesses, this judgment will be better understood if I reverse this order.

Plaintiffs' evidence

Evidence of Ms. Webster

119. Ms. Webster continues to live alone at HH since Mr. Rollo, co-owner of the house and her former partner, left in March 2021. On foot of the principal judgment, the plaintiffs' solicitors wrote to the defendant on 15th March 2024, proposing arrangements for mediation and asking whether, pending mediation, the defendant would mitigate the noise nuisance in response to the court's findings. The defendant did not agree to any mitigatory measures pending mediation.

120. A mediation agreement was signed on 27th June 2024, [26] which provided that the defendant would implement "an iterative process of trial and error to achieve a restricted operation of T2 so that its operation does not give rise to excessive AM and WTN". The defendant would trial different modes during the mitigation period of July to September 2024. The precise design of the trial was a matter for the defendant and not the plaintiff. The plaintiffs agreed that the defendant could place noise monitoring equipment "on their land" at HH and that Ms. Webster would keep a noise diary to record the impact of the noise. It was also noted that the plaintiffs may want to place noise monitoring equipment externally and/or internally at HH and that any raw data from the plaintiffs' noise monitoring equipment would be exchanged simultaneously with the defendant's raw data.

121. The defendant's acoustic expert, Mr. Carr, placed noise monitoring equipment in the front and rear gardens of HH. In addition, Mr. Daniel Baker, Acoustic Consultant, was engaged to undertake outdoor and indoor monitoring on behalf of the plaintiff. External monitoring was carried out in the rear garden and internal monitoring was carried out in the same ground floor back bedroom as previously.

122. Ms. Webster's evidence was that the noise from the turbines was unchanged over the two month mitigation trial period. It remained most intrusive in the evenings and at night time. There was no noticeable change in the AM or in the WTN levels. Ms. Webster continues to find it difficult to enjoy her time at HH and her sleep remains disturbed. Ms. Webster's evidence was that seven and half years after her first complaint to Mr. Brazil, she continues to suffer intrusive, dominant and unreasonable WTN, which has all of the features previously found to exist by the court: "The noise rises and falls, it's not a single instance like a car passing where it passes very quickly or a dog barking even. It's unpredictable. The intensity,... rises and falls. It can be quite thumpy, then it can go quiet, then it can go up and down and so on and so on."

123. Aside from the fact that she views the nuisance as remaining unabated, three features of Ms. Webster's evidence bear emphasiss.

124. First, Ms. Webster is stressed and worried about the wind turbine. She has been worn down by the WTN and finds it increasingly difficult to stay in the house. She is understandably disappointed by the approach to the mitigation process in which the defendant trialled only one different operating mode as part of what was intended to be a "trial and error exercise".

125. I formed the impression that Ms. Webster's disappointment and frustration, justifiable though they may be, now impact her perception and tolerance levels of the WTN. An obvious example of this is Ms. Webster's approach to the issue of audibility of the WTN inside HH. During module 1, Ms. Webster was cross-examined as to whether she equated nuisance with mere audibility internally. The thrust of Ms. Webster's answers was that it was not audibility alone that disturbed her concentration, relaxation and enjoyment and caused her difficulty falling asleep. Rather, it was audibility, combined with low frequency impacts, such as vibration and a sense of pressure. Ms. Webster also relayed being woken "bolt upright" from her sleep by the WTN, which clearly implies a higher level of noise than mere audibility. I believe that there has been hardening in Ms. Webster's position. She now takes the view that if the turbine is audible at all indoors it is thereby a nuisance. I cannot agree. One cannot equate audibility, even internally, with nuisance.

126. Second, in cross-examination, counsel for the defendant laid great emphasis upon para. 70 of this court's judgment reciting Ms. Webster's evidence. I stated "what primarily disturbs Ms. Webster's relaxation and sleep is when the turbine is turning "full tilt"". The defendant relied upon Ms. Webster's use of the phrase "full tilt" in two ways; first it suggests that it is inconsistent with Mr. Stigwood's findings at module 2, that the worst noise intrusion occurs at moderate to higher windspeeds (but not at the highest windspeeds). Second, the defendant maintains that the phrase "full tilt" led it to assume that mitigation was only required at the highest windspeeds, leading it to select the 1,600 mode (which only limits rotational speeds and noise at windspeeds above 7.8 m/s) for the trial and error process.

127. This was an entirely unreasonable position for the defendant to adopt. Ms Webster's use of the phrase "full tilt" cannot justify the defendant's conclusion that the WTN is not a nuisance at windspeeds below the maximum. Ms. Webster's complaints of intrusive WTN usually occur at night when she is in bed and is clearly not counting turbine blade rotations. Rather, her sense that the turbine is turning fast will be a general impression gained from the rhythm of the noise in her room. Even during the day, Ms. Webster would be unable to count the turbine rotations with the naked eye.

128. In any event, the defendant fails to distinguish between the court's recital of Ms. Webster's evidence at para. 70 and the court's findings. The court did not find that the WTN was most intrusive, still less that it was only intrusive, when the turbine was turning at its very fastest level. Rather, I concluded at para. 631 that whilst this would potentially need to be revisited in module 2, it was likely that the worst features of the WTN were associated with at least "moderately higher speeds of rotation". Similarly, at para. 590, I found that "at moderate to high speeds of rotation" the impact of the WTN far exceeds masking levels and is the primary noise experienced in the environment.

129. This court's reference to moderate to high windspeeds was based in part on my finding that the WTN at the time of my site visit to the plaintiffs' houses did not give rise to nuisance. Nuisance therefore arises at windspeeds greater than 3.8 m/s to 4.8 m/s. It follows that my reference to moderate to high windspeeds may be interpreted as windspeeds above 5m/s in any event. In addition, the evidence at module 1 was that the turbine reaches its maximum speed of rotation at 9 m/s and that, beyond that, the WTN does not increase with rising wind speeds. Further, at very high windspeeds background wind noise progressively increases masking the WTN. These factors in themselves imply that any assumption that the greatest problems occur at the very highest windspeeds is misplaced. I also found that the WTN was more intrusive at night time, when ambient background levels are low and stable atmospheric conditions both enhance sound propagation and render high AM values and thump AM more prevalent.