Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

High Court of Ireland Decisions

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> High Court of Ireland Decisions >> Chubb European Group SE & Ors v Perrigo Company PLC & Ors (Approved) [2024] IEHC 9 (11 January 2024)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/ie/cases/IEHC/2024/2024IEHC9.html

Cite as: [2024] IEHC 9

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

THE HIGH COURT

COMMERCIAL

[2024] IEHC 9

RECORD NUMBER 2021/3571P

BETWEEN

CHUBB EUROPEAN GROUP SE (FORMERLY ACE EUROPEAN GROUP LIMITED),

AIG EUROPE SA (FORMERLY AIG EUROPE LIMITED), AXIS SPECIALTY EUROPE SE,

ALLIANZ GLOBAL CORPORATE & SPECIALTY SE,

ALLIED WORLD ASSURANCE COMPANY (EUROPE) DESIGNATED ACTIVITY COMPANY (FORMERLY ALLIED WORLD ASSURANCE COMPANY (EUROPE) LIMITED),

LIBERTY MUTUAL INSURANCE EUROPE SE (FORMERLY LIBERTY MUTUAL INSURANCE EUROPE LIMITED),

XL INSURANCE COMPANY SE,

ZURICH INSURANCE PLC,

QBE EUROPE SA/NV (FORMERLY QBE INSURANCE (EUROPE) LIMITED)

and

LLOYD'S INSURANCE COMPANY SA

PLAINTIFFS

AND

PERRIGO COMPANY PLC, JOSEPH PAPA, JUDY BROWN, MARC COUCKE, LAURIE BRLAS, JACQUALYN A FOUSE, ELLEN R HOFFING, MICHAEL R JANDERNOA, DONAL O'CONNOR, GARY COHEN, HERMAN MORRIS JR, GERALD K KUNKLE JR, JOHN HENDRICKSON, RONALD WINOWIECKI, DOUGLAS BOOTHE, DAVID GIBBONS and RAN GOTTFRIED

DEFENDANTS

JUDGMENT OF Mr Justice Twomey delivered on the 11th day of January, 2024

INTRODUCTION

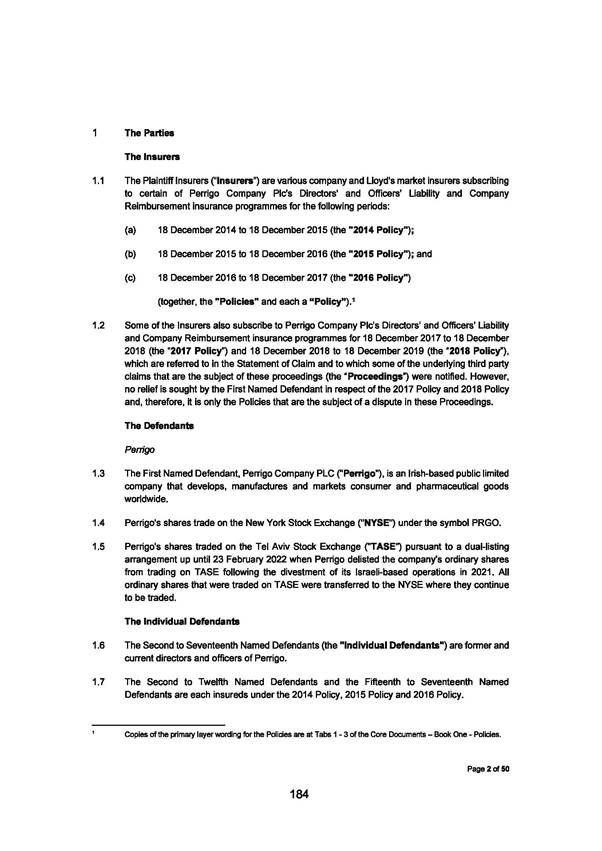

1. This case, which involves the interpretation of insurance contracts, was listed for 12 days, yet it ended up running for just 7 days. As the manner in which this saving of court time was achieved may be of more general application, it is to be noted that it arose from the fact that, prior to the trial, the lawyers involved had prepared an Agreed Statement of Facts. The complexity of the factual background to this case is illustrated by the fact that the Agreed Statement of Facts runs to 50 closely typed pages. As these facts were agreed by the parties in advance of the trial, there ended up being a 42% saving of a scarce public resource (court hearing time). This is because this Court was saved having to spend days hearing evidence regarding those facts, since they had been agreed by the parties. In addition to the saving of court hearing time, there was also a saving of judgment writing time, as it was not necessary for this Court, after the hearing, to carefully sift through all the evidence in order to make various findings of fact, upon which to base the Court's conclusions on the legal issues. Therefore, as well as being in the public interest, there can also be a self-interest for the parties in providing an Agreed Statement of Fact, since the parties are likely to receive their judgment sooner.

2. While this approach is not suitable for every case (e.g. in a dispute on a point of law), the finalisation of an Agreed Statement of Facts will, in many situations, lead to a significant reduction in the amount of court hearing time, for the benefit of other litigants waiting to have their cases heard, and a reduction in waiting times for judgments, for the benefit of the parties.

3. As regards those agreed facts, they are set out in the Appendix to this judgment (and capitalised terms which are used in this judgment, but not defined therein, are defined in that Agreed Statement of Facts). Accordingly, it is not necessary to repeat those facts in any detail in the body of the judgment. However, in very brief summary, it is sufficient to note that certain directors of the first defendant ("Perrigo"), a company incorporated in Ireland, were accused of having falsely inflated that company's true value in order to persuade the shareholders in Perrigo to reject a financially attractive offer for their shares ($179 per share) from another company, Mylan ("Mylan Offer").

4. The directors of Perrigo allegedly received millions of dollars in bonus payments from Perrigo for successfully resisting the takeover bid by Mylan. Shortly thereafter, the share price dropped to $89 per share and it is alleged that this drop occurred when the truth of Perrigo's financial position became clear. As a result, shareholders in Perrigo took a number of class actions in the US against Perrigo and its directors. Perrigo had Directors' and Officers' and Company Reimbursement Insurance to cover, inter alia, legal expenses and costs incurred by the directors, in the event of any claims against them in the exercise of their duties.

5. This case is concerned with a consideration of the terms of those policies in the aftermath of the failed Mylan Offer. It involves the interpretation of various insurance policies between the insured, Perrigo, and the insurers, i.e. the plaintiffs, a number of insurance companies represented by the first plaintiff ("Chubb"). The key question for determination by this Court concerns the interpretation of an aggregation clause in the 2014 Policy.

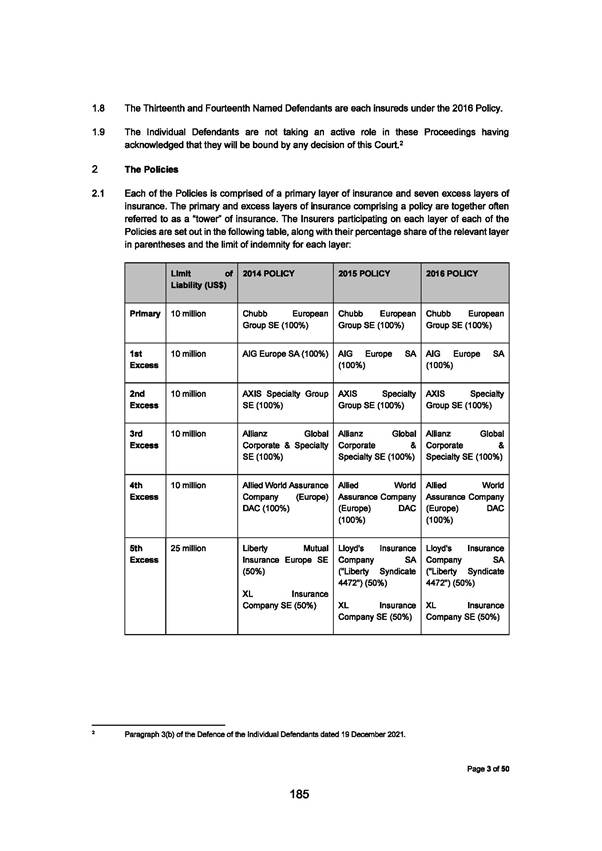

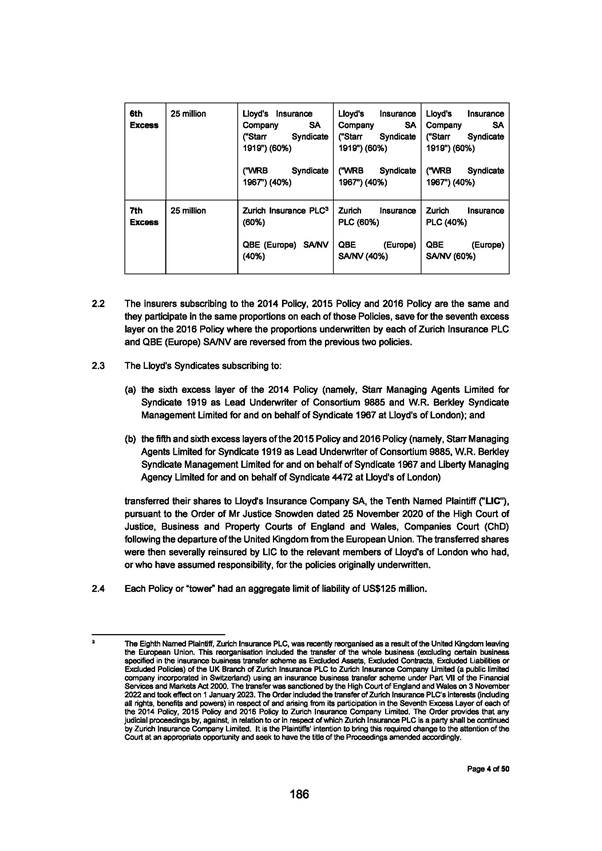

6. In very general terms, an aggregation clause is relevant where there are two separate claims made in separate years against an insured. Normally, the first claim would be treated as being made under the first year's insurance policy and the later claim as being made under the subsequent year's policy. However, an aggregation clause provides that, in certain circumstances, the later claim is treated as a single claim with the first claim, and so both claims are treated as being made under the first year's policy. In this way, both claims are subject to the limits on the first year's policy and any retention on that year's policy.

7. Aggregating claims from two separate years to one year's policy can be advantageous to the insurer or the insured depending on the circumstances. It is for this reason that aggregation clauses 'require a construction which is not influenced by any need to protect the one party or the other' per Hobhouse L.J. in Lloyds TSB General Insurance Holdings Ltd and others v Lloyds Bank Group Insurance Co Ltd [2003] UKHL 48 at para [30].

8. In this instance, it seems clear that aggregation would be advantageous to the insurer, Chubb. This is because Chubb is alleging, and Perrigo is denying, that certain later claims made against Perrigo, after the first claim against the 2014 Policy, should be aggregated back to the 2014 Policy. On the other hand, Perrigo is arguing that the claims made after this first claim should not be aggregated back, but should be responded to by policies which were active when the later claims were made, i.e. the 2015 Policy and the 2016 Policy. To explain the commercial significance to the parties of whether the claims are aggregated back to the 2014 Policy or not, Chubb pointed out that each year's policy has a limit on the insurance of $125 million. Thus, for example, if Perrigo had a claim of $200 million in 2015 and a claim of $50 million in 2016, and if the claims are not aggregated back to 2015, then Perrigo would receive a total of $175 million from Chubb in respect of both claims (i.e. $125 million maximum in 2015 and $50 million in 2016). However, if the 2016 claim is aggregated back to 2015, then Perrigo only receives $125 million in respect of both of these claims. Thus, in this example, Perrigo is down, and Chubb is up, $50 million as a result of aggregation.

9. In other circumstances, aggregation could be financially advantageous to the insured. For example, the retention under the policies is $1 million (i.e. the amount an insured has to pay on each claim, before the insurer will pay) and so aggregating the amount of a 2015 claim and a 2016 claim (of say $900,000 each) to the 2015 Policy would lead to the retention on that year's policy of $1million to be exceeded (by $800,000). In this example, the result of the aggregation is that the Chubb is down, and Perrigo is up, $800,000, as Perrigo gets paid the $800,000 from Chubb, that it would not have received if the claims had not been aggregated, but instead had been spread over two years.

10. In broad terms, the aggregation clause in this case provides that if a wrongful act gives rise to a claim which was notified under the 2014 Policy, then if a 'similar or related' wrongful act gives rise to a claim in later years, then those later claims are aggregated back to the 2014 Policy. Accordingly, the key issues in this case are, firstly what is meant by a 'similar or related' wrongful act when that term is used in an aggregation clause, and secondly, whether the wrongful acts, which form the basis for the first claim against Perrigo under the 2014 Policy, are 'similar or related' to the wrongful acts, which form the basis of the later claims which were made against Perrigo.

11. The first claim notified by Perrigo under the 2014 Policy, i.e. the Mylan Counterclaim, was an application by Mylan in the US for an injunction to prevent Perrigo allegedly making misrepresentations to shareholders in order to defeat the Mylan Offer. The subsequent claims involve, inter alia, class actions taken in the US against Perrigo, by its shareholders, alleging financial loss as a result of alleged misrepresentations made by Perrigo in order to defeat the Mylan Offer. While the events relevant to this case occurred almost exclusively in the US, the relevant policies of insurance, taken out by Perrigo, are subject to Irish law. Hence, the interpretation of the relevant clauses of the insurance policies are subject to determination by this Court under Irish law.

12. In addition to considering the aggregation clause, this judgment also considers a specific exclusion from cover in the 2016 Policy regarding a claim (known as the Roofers Complaint), which had been notified under the 2014 Policy and the 2015 Policy. However, after that 2016 Policy was written, the proceedings in the Roofers Complaint were amended to include new wrongful acts against Perrigo, not included in the original Roofers Complaint. The question therefore arises as to whether it is just the Roofers Complaint, or the Amended Roofers Complaint, which is excluded from cover under the 2016 Policy.

13. The judgment also considers whether a derivative action taken in the US (the 2019 Derivative Action) against Perrigo qualifies for cover under the 2014 Policy. In very general terms, a derivative action in the US involves a shareholder in a company bringing a claim, on behalf of that company, with the company as a nominal defendant, seeking authority to pursue a claim against third parties, which it is alleged the company should have pursued. Since, the company is only nominally a defendant, a key issue is whether a derivative action is a claim against the company, so as to be covered by a policy that provides insurance cover for claims against the company.

14. Finally, it should be noted that this judgment describes the alleged wrongful acts against Perrigo and its directors as 'wrongful acts'. It does so for ease of reference but also because the term 'wrongful act', as used in the relevant aggregation clause, is defined as including 'alleged' wrongful acts. It is to be noted that nothing turns on whether the alleged wrongful acts turn out to be a wrongful or not. This is because the issue in this case is not whether alleged wrongful acts are in fact wrongful. Rather it is whether Chubb has to provide insurance cover for the legal and other costs of Perrigo and its directors in defending the alleged wrongful acts, irrespective of whether they turn out to be wrongful or not. Thus, where this judgment refers to wrongful acts on the part of Perrigo or its directors, it is important to note that this is a reference to that term as defined in the relevant policy, i.e. as an alleged wrongful act. In addition, for ease of reference, the wrongful acts are described in this judgment as having been done by Perrigo, although in most cases they are alleged to have been done by the directors and former directors of Perrigo.

BACKGROUND

15. While the key issue in this case can, and has been, easily stated, the factual background to the original claim made under the 2014 Policy and the claims which have been made under the subsequent policies (the 2015 Policy and the 2016 Policy), is considerably more complex.

Paragraphs 6.1 to 7.2 of the Agreed Statement of Facts give a useful summary of the background to the litigation between Perrigo and Mylan, which led to the Mylan Counterclaim against Perrigo. The Mylan Counterclaim alleges that Perrigo made a series of misrepresentations regarding, inter alia, the Mylan Offer, in order to persuade shareholders in Perrigo to reject that offer. The Mylan Counterclaim was notified by Perrigo to the 2014 Policy. Clause 5.1(iii) of the 2014 Policy states:

"If a single Wrongful Act or act or a series of related Wrongful Acts or acts give rise to a claim under this Policy then all claims made after the expiry of this Policy arising out of such similar or related Wrongful Acts or acts shall be treated as though first made during this Policy Period."

16. For the purposes of this aggregation clause, the Mylan Counterclaim contains the first set of wrongful acts, to which claims made 'after the expiry of the [2014] Policy' are compared, to determine if those later wrongful acts are 'similar or related' to them. If they are then those later wrongful acts are 'treated as though first made during the [2014] Policy Period'. The later wrongful acts are contained in four subsequent claims, which are considered in detail below i.e. the Roofers Complaint, the Keinan Complaint, the Amended Roofers Complaint and the Carmignac Complaint.

17. However, before doing so, it is necessary to have regard to the law relevant to the interpretation of aggregation clauses in insurance contracts.

LAW APPLICABLE TO THE INTERPRETATION OF AGGREGATION CLAUSES

18. There was no disagreement between the parties that the principles set out by Lord Hoffmann, in Investors Compensation Scheme Ltd v West Bromwich Building Society [1998] 1 All ER 98 at pages 114 - 115, are applicable to the interpretation of the insurance contracts in this case. These principles were most recently adopted by the Supreme Court in the case of Law Society of Ireland v Motor Insurance Bureau of Ireland [2017] IESC 31 at para [7] and it is not proposed to set them out herein. However, of particular importance in this case is the fourth principle, i.e. that the meaning which a document conveys to a reasonable man is not the same thing as the meaning of its words to be found in a dictionary. In this regard, Lord Hoffmann makes clear that the meaning of a document is what the parties using those words, 'against the relevant background', would reasonably have understood the document to mean.

19. Since in this case we are dealing with the specialised world of insurance contracts, and within that world, the even more specialised world of aggregation clauses, the 'relevant background' for the interpretation of those clauses has particular importance. Thus, in considering what is meant by 'similar or related', when that term is used in an aggregation clause, it is not what a dictionary says those terms mean, that is relevant. For example, one might be 'related' to a person by blood or marriage, but this is clearly not the meaning of that term in Clause 5.1(iii) of the 2014 Policy. Instead, regard must be had to the following case law on insurance contracts to determine the 'relevant background' for the interpretation of the term 'similar or related' in the aggregation clause in this case.

Aggregation clauses generally

20. First, it is necessary to consider aggregation clauses generally. As regards the purpose of those clauses, in the English Court of Appeal case of Scott v Copenhagen Reinsurance Co (UK) Ltd [2003] EWCA Civ 688, at para [12], Rix L.J. stated that:

"There were no submissions as to how, if at all, the function of an aggregation clause might assist this court to resolve the issue before it. I suppose, however, that its function is to police the imposition of a limit by treating a plurality of linked losses as if they were one loss. For this purpose the losses have to be identified by a unifying concept: in this case 'one event', or strictly speaking 'arising from one event'". (Emphasis added)

21. In a similar vein, in the English High Court case of AIG Europe Limited v OC320301 LLP & Ors [2015] EWHC 2398 (Comm), Teare J. noted at paragraph [30] that:

"The aim or object of the [aggregation] clause is to permit claims to be aggregated for the purpose of applying the limit of the insurer's liability per claim."

At para. [68] of Scott, Rix L.J. went on to note that:

"A plurality of losses is to be regarded as a single aggregated loss if they can be sufficiently linked to a single unifying event by being causally connected with it. The aggregating function of such a clause is antagonistic to a weak or loose causal relationship between losses and the required unifying single events. This is the more easily seen by acknowledging that, once a merely weak causal connection is required, there is in principle no limit to the theoretical possibility of tracing back to the cause of causes. The question therefore in my judgement becomes: is there one event which should be regarded as the cause of these losses so as to make it appropriate to regard these losses as constituting for the purposes of aggregation under the policy one loss" (Emphasis added)

22. Based on the foregoing, it is clear that, in considering an aggregation clause, this Court is considering a 'unifying concept', for treating more than one loss as one loss. In this case, the unifying concept is that the two sets of losses arise from similar or related acts. Thus, to take the first claim after the Mylan Counterclaim, i.e. the Roofers Complaint, the question is, are the wrongful acts in the Roofers Complaint similar or related to the wrongful acts in the Mylan Counterclaim, such that it is appropriate to regard the two sets of losses 'as constituting for the purposes of aggregation under the policy' one loss , and so apply 'the limit of the insurer's liability per claim', and in this way restrict Chubb's liability to the limit on the 2014 Policy?

23. In deciding this question, regard must be had to the wrongful acts 'in the round'. This is clear from the UK Supreme Court case of AIG Europe Ltd v Woodman [2017] UKSC 48 at para [25]. There, Lord Toulson noted that that when considering whether two or more transactions were subject to an aggregation clause, the transactions were:

"to be judged not by looking at the transactions exclusively from the viewpoint of one party or another party, but objectively taking the transactions in the round."

While that case involved 'transactions', rather than 'wrongful acts', there is no reason in principle why this approach should not be taken when one is comparing wrongful acts, for the purposes of determining whether they aggregate back to a previous year's policy.

The wording of the aggregation clause is 'critical'

24. There are a number of other observations regarding aggregation clause which need to be borne in mind, when they are being considered by the courts. The first is that the words chosen by the parties for their aggregation clause is critical. This is clear from the judgment of Lord Hoffmann in the House of Lords decision in Lloyds TSB General Insurance Holdings Ltd and others v Lloyds Bank Group Insurance Co Ltd [2003] UKHL 48, at para [17]. He stated that:

"The choice of language by which parties designate the unifying factor in an aggregation clause is thus of critical importance and can be expected to be the subject of careful negotiations; as Lord Mustill observed in the AXA case [1990] 3 All ER 517 at 526, [1996] 1 WLR 1026 at 1035, among players in the reinsurance market 'keen interest [is] shown... in the techniques of limits, layers and aggregations'." (Emphasis added)

Thus, the actual words which Chubb and Perrigo have chosen for their aggregation clause is an important part of the 'relevant background' when interpreting their contracts.

An 'event' aggregation clause v. an 'originating cause' aggregation clause

25. Another part of that 'relevant background' is the type of aggregation clause chosen - whether an 'event' aggregation clause or an 'originating cause' aggregation clause. Thus, one critical aspect of the 'careful negotiations' to which Lord Hoffmann refers is whether the insured and the insurer agree to an aggregation clause in which the 'unifying factor', which leads to the aggregation of the disparate claims, is an 'event' or an 'originating cause/underlying cause' (referred to hereinafter as just an 'originating cause'). It is clear from the Lloyds case that there is an important difference between an 'event' clause and an 'originating cause' clause (and indeed, as noted below, a difference in the cost of the insurance, depending on which clause is agreed). This is clear from para [14] of Lord Hoffman's judgment (in which he referenced the High Court judgment of Moore-Bick J. which was under appeal):

"Moore-Bick J said ([2001] 1 All ER (Comm) 13 at 24 (para 24)) that the purpose of an aggregation clause was:

'... to enable two or more separate losses covered by the policy to be treated as a single loss for deductible or other purposes when they are linked by a unifying factor of some kind [....]

26. At para. [16], Lord Hoffman continued:

An 'event', [Lord Mustill in AXA Reinsurance (UK) Ltd v Field [1996] 3 All ER 517] said, was 'something which happens at a particular time, at a particular place, in a particular way'. A 'cause' on the other hand, was less constricted: it could be a continuing state of affairs or the absence of something happening. The word 'originating' was also in his opinion chosen 'to open up the widest possible search for a unifying factor'. This meant that in the AXA case the incompetence of a Lloyds underwriter was not an 'event' giving rise to the losses under a number of separate policies which he had written on behalf of various syndicates, whereas in [Cox v Bankside Members Agency Ltd [1995] 2 Lloyd's Rep 437] it had been held to be the 'originating cause' of such losses" [....].

27. At para [25], Lord Hoffmann noted that the 'underlying cause' clause which was the 'unifying factor' for the aggregation of disparate claims in that case was, in contrast to an 'event' clause, a very broad unifying factor:

"It means that the parties started by choosing a very narrow unifying factor: not 'any underlying cause', not 'any event' or even 'any act or omission', but only and specifically an act or omission which gives rise to the civil liability in question. Having chosen this as the opening and, one must assume, primary concept to act as unifying factor, they have then, by a parenthesis, produced a clause in which the unifying factor is as broad as one could possibly wish." (Emphasis added)

28. The significant difference between an event clause and an originating cause clause is also illustrated by the English Court of Appeal case of Spire Healthcare Ltd v Royal & Sun Alliance Insurance Ltd [2022] EWCA Civ 17, where at para [21], Andrews LJ stated that:

"Aggregation clauses like this one, which refer to claims or occurrences "consequent on or attributable to one source or original cause", use a traditional and well-known formula to achieve the widest possible effect as Longmore LJ (delivering the judgement of the court) stated in AIG Europe Ltd v OC320301 LLP [2017] 1 All ER 143, para 21. Whilst the decision of the Court of Appeal in that case was overturned by the Supreme Court in AIG v Woodman (above), those observations were not disapproved. Indeed, they are consistent with a long line of earlier authorities." (Emphasis added)

29. Another general point of relevance to the choice by Perrigo and Chubb of an 'event' clause, rather than a 'originating cause' clause, is made by Lord Hobhouse at para [31] of Lloyds, where he states:

"Another preliminary observation which needs to be made, which is true of very many professionally drafted commercial and financial contracts, and is particularly true in the present case, is that there are often well-established alternatives open to the parties in the drafting of their agreement. The choice made from among these alternatives represents part of the bargain struck by the parties and must be respected by anyone (judge or arbitrator) adjudicating upon a dispute arising under the document. As noted by Lord Mustill in AXA Reinsurance (UK) LTD v Field [1996] 3 All ER 517 at 522 - 527, [1996] 1 WLR 1026 at 1031 - 1035, and, as I will explain below, aggregation clauses come in different well-established forms. The clause in the present case is no exception. The form it takes is plain and apparent from the language which the parties have used." (Emphasis added)

30. At para [51], he states:

"Returning to the aggregation clause in the present policy, there are no words of equivalent strength to those found in the AXA and Municipal cases - 'attributable to' - 'a single source' - 'originating cause' [....] The parties could, if they had so chosen, have used a clause such as that found in the AXA or Municipal cases. They chose not to and, no doubt, the cost of obtaining insurance cover was reduced as a result. Their choice should be respected. (Emphasis added).

31. There is no doubt that the disputed clause in this case (Clause 5.3(iii) of the 2014 Policy) is an 'event' aggregation clause and not an 'originating' aggregation. It is also clear that claims against Perrigo would be more likely to be aggregated with an 'underlying cause' (or 'originating cause') clause, than they would be with an 'event clause', and so more likely that that there would be an application of 'the limit of the insurer's liability per claim'. This explains Lord Hoffmann's reference to why choosing an originating cause clause, over an event clause, should lead to a reduction in insurance costs for the insured. This is because it is more likely, with an originating cause clause, that claims from subsequent years will be aggregated to an earlier year and so it is more likely that the insured will make a saving of the maximum pay-out on the policy, albeit that the insured may benefit from exceeding any retention paid.

32. Applying Lord Hoffmann's logic, Perrigo would be expected to have paid more for the benefit of an 'event' clause, than if it had agreed to an 'originating cause' clause. This therefore is part of the 'relevant background' when interpreting Clause 5.1(iii) and as noted by Lord Hoffmann, this choice of a more restricted clause should be 'respected' by this Court.

33. This aspect of the 'relevant background' is further highlighted by the fact that, when it came to the 2016 Policy, the parties negotiated an originating cause clause, rather than an event clause. This is clear from Clauses 5.2 and 3.51 of the 2016 Policy, which state that:

"5.2 A Single Claim shall attach to the Policy only if the notice of the first Claim, Investigation or other matter giving rise to a claim under a policy, that became such Single Claim, was given by the Insured during the Policy Period."

"3.51. Single Claim means all Claims or Investigations or other matters giving rise to a Claim under this Policy that relates to the same originating source or cause or the same underlying source or cause, regardless of whether such Claims, Investigations or other matters giving rise to a claim under this Policy involve the same or different claimants, Insureds, events, or legal causes of action".

34. This aggregation clause provides that the unifying factor for the aggregation of disparate claims is that they arise from the same originating/underlying cause or source. This is to be contrasted with the aggregation clause, with which this Court is concerned, in Clause 5.1(iii) of the 2014 Policy, in which the unifying factor is more restricted as the claims must arise from similar or related wrongful acts. This contrast between these two clauses highlights that it is the nature of the wrongful acts, not their underlying cause, which is the unifying factor in this case, and which will determine whether it is appropriate for them to be aggregated into one loss and so for the insurer's one year limit to apply to the claims.

35. Thus, in this case, this Court does not have to determine whether the wrongful acts forming the basis for the subsequent claims (in the Roofers Complaint, the Keinan Complaint, the Amended Roofers Complaint and the Carmignac Complaint) arise from the same cause or the same underlying source as the claims in the Mylan Counterclaim e.g. do all the wrongful acts arise from rejecting the Mylan Offer. Indeed, in this regard, counsel for Perrigo accepted that if Clause 5.1(iii) were an originating cause clause, rather than an event clause, there would be a basis for aggregating back the Roofers Complaint, the Amended Roofers Complaint and the Carmignac Complaint to the 2014 Policy, as they, like the Mylan Counterclaim, all arose from the desire to have the Mylan Offer rejected.

36. To summarise this caselaw, all of this is 'relevant background' to concluding what the parties in this case would reasonably have understood the expression 'similar or related' in Clause 5.1(iii) to mean. This is because it is clear to this Court that Clause 5.1(iii) is an event clause, rather than an originating cause clause. It is also clear from the caselaw, that this Court must determine whether the wrongful acts to be compared, are similar or related, not as those terms are generally understood in the English language, but as those terms are understood in the context of an aggregation clause in an insurance policy, where the parties have deliberately chosen an 'event' clause rather than an 'originating cause' clause. This choice was made by the parties in light of the very significant differences between those clauses, including the fact that the cost to an insured of an 'event' clause would be expected to be more. It is important therefore to bear in mind that the parties did not choose an originating cause clause that would have been 'less constricted' or 'as broad as one could possibly wish'. Instead, they opted for the more restricted and less broad 'event' clause. This is because, unlike an originating cause clause, an event clause does not have the 'widest possible effect' and it does not open 'up the widest possible search for a unifying factor' in order to achieve a 'limit of the insurer's liability per claim'.

37. Finally, in the context of aggregation clauses generally, reference should be made to Woodman case at para [22]. There, in the context of an aggregation clause, where the unifying event was 'a series of related matters or transactions', Lord Toulson noted that the determination by a court of whether transactions are related is an 'acutely fact sensitive exercise'. He also observed that it involves 'an exercise of judgment, not a reformulation of the clause to be construed and applied'. While his comments were in the context of related transactions, rather than related wrongful acts, this Court cannot see any reason in principle for them not also being applicable to this Court's consideration of 'similar or related' wrongful acts. However, before undertaking this 'exercise of judgment' as part of this 'acutely fact-sensitive exercise', it is necessary first to consider the treatment of the terms 'similar' and 'related' in other cases involving aggregation clauses.

Meaning of 'similar' and 'related' when used in aggregation clauses

38. In the Woodman case at para [22], Lord Toulson considered the meaning of the word 'related' when it is used in an aggregation clause. He held that:

"Use of the word 'related' implies that there must be some interconnection between the matters or transactions, or in other words that they must in some way fit together [...]"

39. As regards what is meant by 'similar' when it is used in an aggregation clause, Teare J. held in AIG Europe Ltd at para [30] that:

"[T]he requisite degree of similarity must be a real or substantial degree of similarity as opposed to a fanciful or insubstantial degree of similarity. This is not adding words which are not to be found in the clause. Rather it is construing the adjective 'similar' which is found in the clause."

40. While Teare J.'s conclusion, regarding whether the claims should be aggregated, was reversed on appeal, it is important to note that Teare J.'s finding on what was meant by similarity was not challenged on appeal. However, while definitions of 'similar' and 'related' are of some assistance, what is more helpful is the conclusions which have been reached in other cases where those terms are used in 'event' aggregation clauses.

41. In that case, a company called Midas wished to develop holiday homes in Turkey and Morocco for which purpose it engaged the International Law Partnership LLP ("TILP"), which was insured by AIG. Investors' monies were not to be paid over by an escrow agent to Midas until the promised level of security was in place. However, the investors' monies were lost and it was claimed that if TILP had put in place the appropriate level of security this would not have happened. The relevant aggregation clause provided that all claims which were 'similar acts or omissions in a series of related matters or transactions' were to be regarded as one claim.

42. At para [31] of his judgment, Teare J. held that the Turkish and Moroccan claims 'were not identical, but they do not have to be' and he held that there was a 'real and substantial degree of similarity' between them. On this basis he held that they 'arose out of similar acts or omissions' and so were to be aggregated.

43. Although undoubtedly there could be said to be a degree of similarity between the two sets of acts, the Supreme Court held that were not sufficiently similar to be subject to aggregation under that 'event' aggregation clause. This is because in Woodman, Lord Toulson concluded at para [27] that the Turkish and the Moroccan claims could not be aggregated together as they 'related to different sites, and the different groups of investors were protected by different deeds of trust over different assets.'

44. The English High Court case of Discovery Land Company LLC & Ors v Axis Speciality Europe SE [2023] EWHC 779 (Comm), is another case where superficially similar or related acts were held not to be sufficiently similar or related for the purposes of an 'event' aggregation clause. In that case, there were two insurance claims against a firm of solicitors. One related to the wrongful withdrawal by the solicitor (Mr. Jones) of surplus funds from an account belonging to the solicitor's firm, for the purchase of Taymouth Castle (called the 'Surplus Funds Claim'). The other claim was the wrongful withdrawal of funds by that same solicitor arising from a fraudulent loan which had been obtained as a result of security provided by Taymouth Castle (called the 'Dragonfly Claim'). The issue was whether these two claims were to be aggregated pursuant to an aggregation clause, which provided that all claims would be regarded as one claim if they were:

"(c) one series of related acts or omissions'[or]

(e) similar acts or omissions in a series of related matters or transactions"

45. Knowles J. relied on Teare J.'s clarification of the meaning of the word 'similar' when used in aggregation clauses in AIG Europe Ltd, and at para. [162] he stated that:

"AXIS says that 'the surplus funds claim was founded on a misappropriation of funds paid by the client, whereas the Dragonfly Claim was founded on the misappropriation of funds raised by granting a security over property owned by the client is a distinction without a real difference'. I respectfully consider that the difficulty with that proposition is that the distinction which is present in this case is not revealed by that choice and generality of summary. I agree with the Claimants that AXIS's submission that both Claims involved 'thefts of closely connected clients' money by Mr Jones' ignores the detail between the two. In relation to the Surplus Funds Claim the act or omission giving rise to the claim under the policy was the wrongful release of money from the client account, whereas in the Dragonfly Loan Claim the act or omission was, 9 months later, the wrongful arrangement of a facility and charge, drawn down under the facility and then release from the client account. (Emphasis added)

46. This case starkly highlights that the meaning, of 'related' and 'similar' in an everyday context, is very different from its meaning in the context of an aggregation clause. This is because at a 'high level of generality', to use the expression used by Knowles J. at para [159], the acts were clearly related or similar, i.e. they both involved the misappropriation of client funds in the context of the same property (Taymouth Caste). In everyday language it is indeed difficult to disagree with the submissions in that case that the distinction between stealing a client's funds paid in by that client, on the one hand, and stealing clients' funds raised by granting security over a client's property, on the other hand, is a distinction without any real difference. Accordingly, in everyday language, these two acts are similar or related.

47. However, for the purposes of an event aggregation clause in an insurance contract, it is a distinction with a difference, because these two wrongful acts were held by the English High Court not to be similar or related. Thus, in that case wrongfully releasing money from a client account was not sufficiently related to another instance of wrongfully releasing money from a client account (after the wrongful arrangement of a loan facility), even though they both involved the misappropriation by a solicitor of his clients' funds.

48. The case of Bishop of Leeds and another v Dixon Coles & Gill and another [2022] EWCA Civ 1211 is another claim in which superficially similar or related acts were held not to be similar or related for the purposes of an event aggregation clause. It involved claims against a solicitor (Mrs. Box), who had carried out numerous thefts of clients' moneys over a long period of time and on a grand scale. The insurance policy contained a monetary limit for any one claim. It also contained an aggregation clause, which provided that all claims were to be regarded as one claim if they arose from any of the following limbs:

'one act or omission,

one series of related acts or omissions,

the same act or omission in a series of related matters of transactions,

similar acts or omissions in a series of related matters or transactions.'

At para [61], Nugee LJ stated:

"In the present case the effect of Limbs 1 and 2 of the aggregation clause is that the claims have to result from either one act or omission, or from a series of related acts or omissions. It is accepted by Mr Pooles that Mrs Box's dishonesty is not itself an act, and that the acts or omissions are her individual thefts. The question is whether they are sufficiently related to be a series for the purpose of the clause; and that question turns on what the relevant unifying factor is. That, according to Lord Hoffmann, is to be found in the language of the aggregation clause."

49. At paragraph [72] he states:

"[Mrs Box's thefts] are not the very same act, repeated a number of times. They are no doubt similar acts, all flowing from her dishonesty; but this is not enough to make them a series of related act for the purposes of aggregation." (Emphasis added)

50. This case therefore highlights, as the Discovery case does, that while two thefts of clients' moneys by the same solicitor might in everyday language be said to be related or similar acts, because, inter alia, they flow from dishonesty, it is a very different matter where the interpretation of 'similar' or 'related' is 'for the purposes of aggregation' under the terms of an event aggregation clause.

51. A case which provides an example of a factor which can make wrongful acts similar or related for the purposes of an event aggregation clause is the Australian case of Bank of Queensland v AIG Australia Limited [2019] NSWCA 190, in which the clause provided that 'claims arising out of, based upon or attributable to one or a series of related wrongful acts' were deemed to be a single claim.

52. The case concerned the Bank of Queensland ("Bank"), which, through an intermediary, DDH, operated 'Money Market Deposit Accounts' for its clients. The clients appointed SFP as their financial planner, and SFP, through DDH, arranged those deposits for those clients. Unauthorised withdrawals were made from the deposits by SFP and the clients sought to recover their losses from the Bank as they claimed that the Bank's agent (DDH) knew that SFP was operating a Ponzi scheme.

53. The New South Wales Court of Appeal held that the wrongful acts were related for the purposes of the aggregation clause. This was because each claim against the Bank was based on its vicarious liability for the wrongful acts of its agent in paying out the monies out of the client account. In particular, it was held that the unifying factor rendering all of the wrongful acts 'related' was the fact that all of the wrongful acts were engaged in by the Bank, while it was deemed to have known, through its agent, of SFP's fraudulent Ponzi scheme.

54. In this context, it is relevant to noted that in the Bishop of Leeds case, the dishonest acts (the thefts by the solicitor) could be said to be 'related' as a matter of ordinary language, but not 'related' such as to aggregate under an insurance policy with an event aggregation clause. In contrast, in the Bank of Queensland case, the opposite conclusion is reached, where the dishonest appropriation of monies is held to be 'related' such as to aggregate under an insurance policy, because of the knowledge of the Bank (through its agent) that the funds were being misappropriated.

55. At para [13] Bathurst CJ noted that the acts must not only be wrongful but the 'acts themselves must be related or interconnected'. He was clearly conscious of the important difference between an event clause, in that case, and other cases involving originating cause clauses, since he referred at paragraph [14] to the judgment of Lord Mustill in Axa Reinsurance (UK) plc v Field [1996] 2 Lloyd's Rep 233 (relied upon in the Lloyds case) and noted that the courts have been 'astute in this area to distinguish between clauses where the unifying factor is an act or where it is a cause'. This is also clear from paragraph [16] where he referred to the Lloyds case and noted that:

"As both Lord Hoffmann and Lord Hobhouse pointed out in the passages from the speeches cited by MacFarlan JA, the unifying act required by the aggregation clause was to be found in the acts or omissions not the cause of the acts or omissions" (Emphasis added)

He continued at para [26] that:

"[E]ach claim was attributable to a Wrongful Act by the agent in paying money out of the claimant's individual "Money Market Deposit Account" to the client's financial planner [SFP] with knowledge that the financial planner was using the funds received in a fraudulent Ponzi scheme. In making the payments with that knowledge, the agent was alleged to have breached its contractual and fiduciary obligations for which [the Bank] was said to be vicariously liable." (Emphasis added)

He concluded at para. [28]:

"Further, the circumstances in which the payments were made were such as to constitute them 'related Wrongful Acts'. Each of the claimants had the same financial planner, a representative of which was an authorised signatory on each of the claimants' 'Money Market Deposit Account[s]'. The breach in each case was identical, namely, making the payment with knowledge of the fraudulent activities of the financial planner. In the circumstances, the Wrongful Acts were related Wrongful Acts for the purpose of the clause." (Emphasis added)

MacFarlan JA agreed that the wrongful acts were 'related'. It is relevant to note that little or nothing turned on the fact that the aggregation clause states that the wrongful acts should be a 'series' of related wrongful acts. This is because at paragraph [94], he states that:

"the use of the word "serious" in the aggregation,/disaggregation provision in the present Policy adds little, if anything to the concept of relatedness of the acts which is integral to the provision. In the context of the present dispute, I read it, at most, as emphasising the need for the relent relevant acts to be "related"".

56. For this reason, the aggregation clause in the Bank of Queensland is the closest to the wording in Clause 5.1(iii) of any of the cases opened to the Court. This is also clear from para [102]:

"The aggregation clause in the present case is not an explicitly cause-based clause similar to the clauses under consideration in the Cox and Municipal decisions to which Lord Hoffmann referred. Nor however is it, as the clause in Lloyds TSB was found to be, devoid of an indication as to the connecting factor that would make the Insureds' acts "related" (whether as part of a "series" or otherwise) for the purposes of clause. An identification of a sufficient connecting factor is in my view to be found in the present clause's reference to Wrongful Acts. Whilst in Lloyds TSB the acts certainly had to be wrongful in order to be relevant to the claim for indemnity, the aggregation clause did not refer to their wrongfulness. The present clause does however do that. Moreover it does not use the somewhat clumsy expression used in the Lloyds TSB clause of a "related series of acts or omissions" but more clearly identifies the relevant question as whether the Wrongful Acts are related." (Emphasis added)

At para [59] he states that:

"[T]he Insurers contend that [the Bank]'s alleged Knowledge of Fraud is not a unifying factor which it is permissible to consider in determining whether the Wrongful Acts are 'related'".

However, he clearly rejected the argument that the Bank's knowledge of the fraud was not a unifying factor, since he found that, because of this knowledge, they were related. This is clear from para [103] where he concludes that:

"In my opinion, the fact that all of the Wrongful Acts alleged in the [amended statement of claim] are alleged to have been wrongful (albeit in the case of some acts, inter alia) on the basis that they were engaged in by [the Bank] as part of SFP's Ponzi scheme with knowledge of SFP's fraud is a unifying factor rendering them related for the purposes of the aggregation clause". (Emphasis added)

57. It is clear from the foregoing caselaw that the expressions 'similar' and 'related' are to be very carefully interpreted in the context of event aggregation clauses, as their meaning is different than their general meaning in a dictionary. Thus, while one might have thought that a claim that a bank's agent's release of funds to a Ponzi scheme is per se related to another claim that the same bank's agent released funds to a Ponzi scheme, this is not the case in the context of an event aggregation clause. Something more is required to make them related for the purposes of an event aggregation clause. Accordingly, for two wrongful acts of placing investments into a Ponzi scheme to be related in the Bank of Queensland case, it is the knowledge of the agent that the funds were being invested in a Ponzi scheme, which is the unifying factor. In contrast, where there is no equivalent unifying factor, the dishonest acts by solicitors regarding their clients in the Bishop of Leeds case and in the Discovery case were not sufficiently related to each other to lead to aggregation under the event aggregation clause in that case. It is clear therefore that the expressions 'related' and 'similar' are restrictively interpreted as unifying factors when used in event aggregation clauses.

ARE THE WRONGFUL ACTS IN THIS CASE SIMILAR OR RELATED?

58. The wrongful acts which Perrigo is alleged to have committed, which are first in time, are set out in the Mylan Counterclaim. This was duly notified by Perrigo to Chubb when the 2014 Policy was in force. Accordingly, there is no dispute that insurance coverage is being provided by Chubb to Perrigo under the terms of the 2014 Policy for that claim. It is useful at this juncture to set out once again the aggregation clause in Clause 5.1(iii):

"If a single Wrongful Act or act or a series of related Wrongful Acts or acts give rise to a claim under this Policy then all claims made after the expiry of this Policy arising out of such similar or related Wrongful Acts or acts shall be treated as though first made during this Policy Period." (Emphasis added)

Section 3.37 defines Wrongful Act since it provides that:

"Wrongful Act means any proposed or alleged, breach of trust, error, omission, misstatement, misleading statement, neglect or breach of duty or any other matter claimed against an Insured whilst acting in the capacity of an Insured, including but not limited to any violation of the Companies Act 1990, the Company Law Enforcement Act 2001, Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 or any equivalent law, rule or regulation in any other jurisdiction, any matter claimed against an Insured solely by reason of their capacity as an Insured, and an Employment Related Wrongful Act."

59. The key issue therefore in this case is whether the wrongful acts which form the basis of subsequent claims (i.e. the Roofers Complaint, the Keinan Complaint, the Amended Roofers Complaint and the Carmignac Complaint), which were notified by Perrigo to Chubb, are similar or related to the wrongful acts, which form the basis of the Mylan Counterclaim. If they are, they are aggregated back to the 2014 Policy, and do not need to be considered under the terms of the 2015 Policy and/or the 2016 Policy.

60. The first step in this analysis is to consider the nature of the wrongful acts which form the basis of the Mylan Counterclaim.

Mylan Counterclaim

61. The relevant details of the Mylan Counterclaim are set out at para 8.1 et seq of the Agreed Statement of Facts. In brief, the wrongful acts arose from the failed hostile takeover of Perrigo by Mylan. The Deadline for the acceptance of the Mylan Offer by Perrigo shareholders was 13 November 2015, by which date an insufficient number of shareholders had accepted the offer, leading to its rejection.

62. Prior to that date however, Perrigo had, on 17 September 2015, filed an action in the US against Mylan alleging that Mylan had misrepresented certain issues to Perrigo's shareholders in order to persuade them to accept Mylan's Offer for their shares. Mylan responded on 22 September 2015 by filing a counterclaim to Perrigo's complaint (the Mylan Counterclaim) seeking injunctive relief against Perrigo to halt certain misrepresentations, which Mylan alleged Perrigo was making to Perrigo shareholders regarding Mylan's Offer, in order to persuade them to reject Mylan's Offer.

63. In the Mylan Counterclaim, the wrongful acts alleged by Mylan against Perrigo are that, in order to defeat the Mylan Offer, four categories of misrepresentations were made by Perrigo in breach of s 14(e) of the Securities Exchange Act 1934, i.e.

(i) It misrepresented that the tender offer premium contained in the Mylan Offer undervalued Perrigo ("Offer Value Misrepresentation").

(ii) It falsely claimed that the Mylan Offer was dilutive rather than accretive for Perrigo shareholders ("Dilutive Misrepresentation").

(iii) It falsely claimed that Mylan's largest shareholder, Abbott, did not support the takeover attempt ("Abbot Misrepresenation").

(iv) It misrepresented the potential synergies of the combination of Mylan and Perrigo ("Synergy Misrepresentation")

64. On 30 September 2015, Perrigo notified the Mylan Counterclaim to the 2014 Policy (since that policy was in force from 18 December 2014 to 18 December 2015). Much depends in this case therefore on whether the subsequent wrongful acts (which form the basis of the Roofers Complaint, the Keinan Complaint, the Amended Roofers Complaint and the Carmignac Complaint) are similar or related to any of the foregoing wrongful acts (i) to (iv) in the Mylan Counterclaim, i.e. the Offer Value Misrepresentation, the Dilutive Misrepresentation, the Abbot Misrepresentation or the Synergy Misrepresentation.

A.THE ROOFERS COMPLAINT

65. The first in time of the four complaints, subsequent to the Mylan Counterclaim, is the Roofers Complaint, which is set out in para 9.1 et seq of the Agreed Statement of Facts. This is a class action taken in the US by Perrigo shareholders seeking damages from Perrigo. It was filed on 18 May, 2016 against Perrigo and Mr. Joseph Papa (Perrigo's then Chairman and Chief Executive Officer) alleging:

(a) a breach of section 10(b) of the Securities Exchange Act 1934 brought on behalf of purchasers of shares in Perrigo between 21 April 2015 (the day the Perrigo Board rejected the Mylan Offer) and 11 May 2016, and

(b) a breach of section 14(e) Of the Securities Exchange Act 1934 brought on behalf of investors in Perrigo shares as of the Deadline of 13 November 2015.

66. On 6 June 2016 this claim was notified by Perrigo to the 2014 Policy and the 2015 Policy. Chubb claims that the wrongful acts in the Roofers Complaint are 'similar or related' to the wrongful acts in the Mylan Counterclaim (which, it is agreed, are covered by the 2014 Policy). Chubb therefore claims that the Roofers Complaint is, to use the words of Clause 5.1(iii), to 'be treated as though first made' during the period covered by the 2014 Policy, and so is only covered by the 2014 Policy.

Do dissimilarities between the claims mean wrongful acts are not 'similar or related'

67. In claiming that the wrongful acts in the Roofers Complaint are not similar or related to the wrongful acts in the Mylan Counterclaim, Perrigo points to the dissimilarities between the two claims.

68. For example, Perrigo points out that the Roofers Complaint is a class-action taken by shareholders against their company (Perrigo), while the Mylan Counterclaim is a claim for injunctive relief between Perrigo and a third party company, Mylan; that the Roofers Complaint alleges breaches of a different section of the Securities Exchange Act 1934 (s. 10(b)) than that alleged in the Mylan Counterclaim (s. 14(e)); that the Roofers Complaint seeks damages, as distinct from injunctive relief in the Mylan Counterclaim.

69. At this juncture, it is also appropriate to note that in relation to the other claims (the Amended Roofers Complaint, the Keinan Complaint and the Carmignac Complaint), Perrigo points to other dissimilarities between those claims and the Mylan Counterclaim. For example the different time period in those class actions (e.g. the Carmignac Complaint covers the period up to May 2016) on the one hand, and the time period relevant to the Mylan Offer/Mylan Counterclaim (i.e. from the date the offer was originally announced on 6 April 2015 to its rejection on 13 November, 2015), on the other hand. Similarly, Perrigo points out that some of the later claims have different defendants from the Mylan Counterclaim (e.g. in the Keinan Complaint the firm Ernst &Young LLP, which is not a party to the Mylan Counterclaim, is a co-defendant with Perrigo).

70. However, it seems to this Court that these and other dissimilarities between the complaints are not determinative of the task of this Court. This is because this Court's task is to compare the wrongful acts, not the consequences of the wrongful acts, such as the statutory breaches which were alleged arising from those wrongful acts, or the nature of the proceedings/claims which arise from the wrongful acts, or the parties being sued etc. This is because the aggregation clause refers to the similarity or relatedness of wrongful acts, and as pointed out in the Lloyds case, the wording of the aggregation clause is 'critical'.

Thus, the focus of the analysis has to be on the alleged wrongful acts.

Comparing the nature of the wrongful acts

71. The wrongful acts which form the basis of the Roofers Complaint are set out in the Agreed Statement of Facts. It is clear from that document that it is claimed that in order to persuade Perrigo shareholders to reject the Mylan Offer the following allegedly wrongful acts were committed by Perrigo, i.e. that:

(i) it misrepresented that Mylan's offer substantially undervalued Perrigo; ("Value of Offer Misrepresentation")

(ii) it misrepresented that Perrigo would be able to achieve 5%-10% in organic growth as a stand-alone company; ("Organic Growth Misrepresentation")

(iii) it misrepresented that Perrigo was experiencing serious issues integrating the Omega acquisition. ("Omega Integration Misrepresentation")

The relevance or irrelevance of the purpose of the wrongful acts?

72. Counsel for Chubb stated that, when comparing the wrongful acts, which form the basis of the claims (in particular, the Roofers Complaint, the Amended Roofers Complaint and the Carmignac Complaint), and comparing them to the wrongful acts in the Mylan Counterclaim, that:

"The core, the simple fact remains that all of the misrepresentations, all the wrongful acts, are those which are said to have been made for the purpose of inducing shareholders to reject the Mylan tender offer. They all have that in common. And if that is so, that per se must take (sic) them similar, or at the very least, related." (Emphasis added)

Counsel for Perrigo rejected this submission that two wrongful acts are per se similar or related for the purpose an event aggregation clause, if they are made for the same purpose. This Court agrees with Perrigo that just because two acts are made with the same purpose does not per se mean that they are similar or related for the purposes of an event aggregation clause, such as Clause 5.1(iii). This is because it is clear from the caselaw that the terms 'similar' and 'related', when used in an event aggregation clause, are narrowly interpreted. Thus, as Lord Mustill makes clear, an event is something which happens at a particular time, at a particular place, in particular way. Therefore, as we are dealing with an event aggregation clause, the wrongful acts, which are 'events' happen at particular times, places and in a particular way, and it is these events which must be compared to see if they are similar or related, not the purpose of those events or acts. An originating cause clause is very different and as Lord Mustill pointed out, it is much less restricted than an event clause. The Discovery case highlights this point. It illustrates that just because two wrongful acts, such as stealing by a solicitor from a client, are made with the same purpose (to financially benefit a solicitor) does not make them similar or related for the purposes of an event aggregation clause.

73. Chubb also made the following written submission, albeit in the context of Clause 5.2 of the 2016 Policy, which is an originating cause clause, regarding the similarities between the Mylan Counterclaim and the subsequent claims.:

"As mentioned previously, the introductory statements contained in the complaints demonstrate that they flow from the wrongful actions taken by Perrigo and senior officers with a view to defeating the Mylan takeover. This is the essence of the Mylan counterclaim. The subsequent claims have the same underlying source albeit that they contain different material facts said to give rise to their respective causes of action." (Emphasis added)

This submission, while made in a different context, nonetheless does not assist Chubb in its claim, under Clause 5.3(iii), that the subsequent claims should not be aggregated back to the 2014 Policy. This is because, Clause 5.1(iii) of the 2014 Policy is an event clause, not an originating cause clause and so the fact that the subsequent claims have the same underlying source as the Mylan Counterclaim, is not determinative of this issue.

74. Equally however, this Court does not agree with the claim that appeared to be made by Perrigo that in determining whether two or more wrongful acts are similar or related, the purpose behind those wrongful acts is irrelevant to that determination. As already noted in the context of the Woodman case, when dealing with whether an act is similar or related for the purposes of an event aggregation clause, one is dealing with an 'acutely fact-sensitive exercise'. For this reason, all the facts have the potential to impact upon the Court's conclusion that, when looked at 'in the round', the wrongful acts are/are not similar or related. Indeed, just as the presence of a common purpose could be a factor, albeit not determinative, in concluding that two wrongful acts are similar or related, so too the absence of a common purpose could be a factor, albeit not determinative, in concluding that two wrongful acts are not similar or related.

75. Another argument pursued by Perrigo regarding the purpose of the alleged wrongful acts is that there is nothing wrongful about seeking to persuade shareholders to reject a takeover bid, which is of course correct. On this basis, and since one is determining whether two wrongful acts are similar or related, it argued that this militates against a finding that two sets of wrongful acts, in pursuit of this lawful aim, could be similar or related wrongful acts. However, this Court does not agree. This is because, just as it is not determinative (of whether wrongful acts are similar or related) that two wrongful acts have the same purpose, equally it is not determinative that the purpose which is being pursued is lawful or not lawful. The focus is on the nature of the acts, not their purpose, or whether that purpose is lawful or unlawful.

76. Perrigo also sought to emphasise that 'dishonesty' is not an act or an event, when one is dealing with an event aggregation clause. Thus, it seemed to be claiming that simply because two acts are both dishonest does not make them similar or related acts or 'events' for the purposes of an 'event' aggregation clause, on the basis that dishonesty is not an 'event'. It is true that dishonesty is not an act or event. This is evidenced by the Discovery case, since it involved two dishonest acts of theft which were held not to be 'one series of related acts' or 'similar acts or omissions in a related series'. However, while dishonesty per se does not make two wrongful acts similar or related for the purposes of an aggregation clause, the nature of the dishonest acts can be a factor in contributing to a conclusion that two wrongful acts are similar or related for the purposes of an event aggregation clause. This is because this is a very fact-intensive and fact specific analysis and it requires a judgment call to be made on an assessment of all the facts and circumstances.

77. In order to deal with the wrongful acts in the order in which they are alleged, it is proposed firstly to look at the first wrongful act in the Roofers Complaint, i.e. the Value of Offer Misrepresentation.

Wrongful act (i) in the Roofers Complaint - Value of Offer Misrepresentation

78. It is necessary to compare wrongful act (i) in the Roofers Complaint (Value of Offer Misrepresentation) and wrongful act (i) in the Mylan Counterclaim (Offer Value Misrepresentation). The former wrongful act is the claim that Perrigo falsely told investors that the Mylan Offer substantially undervalued Perrigo, while the latter wrongful act is the claim that Perrigo gave misleading statements regarding the size of the exchange offer premium for the shares under the terms of the Mylan Offer. On their face, these two wrongful acts are similar and related and it is difficult to see any distinction between them. In particular, this Court does not accept the attempts at distinction made by Perrigo in its written submissions, that the wrongful acts are not similar or related, because there was a 'different focus' to the wrongful acts in the Roofers Complaint than the wrongful acts in the Mylan Counterclaim (e.g. it is a damages claim in the Roofers Complaint v. injunctive relief in the Mylan Counterclaim, and that it was brought by different classes of shareholders in the Roofers Complaint v. brought by Mylan in the Mylan Counterclaim). This is because, as already noted, it is clear from the wording of Clause 5.1(iii) that the focus must be on the nature of the wrongful acts and not their consequences or the form of the proceedings.

79. When one looks at the nature of these two wrongful acts, it seems to this Court to be very clear that there is a 'real or substantial degree of similarity' between the misrepresentation in the Roofers Complaint, that the Mylan Offer 'substantially undervalues Perrrigo and its growth prospects' (from para 9.5 of the Agreed Statement of Facts), and the misrepresentation in the Mylan Counterclaim, that Perrigo 'inundated its shareholders with false and misleading statements regarding (i) the size of the exchange offer premium' (from para 8.3 of the Agreed Statement of Facts).

80. On this basis, it seems beyond doubt to this Court that wrongful act (i) in the Roofers Complaint aggregates back to the 2014 Policy.

The remaining wrongful acts

81. Before continuing with an analysis of each of the remaining wrongful acts, it is proposed to consider four of the those wrongful acts collectively, i.e. the Organic Growth Misrepresentation, Omega Integration Misrepresentation (which are contained in the Roofers Complaint) and the Collusive Pricing Misrepresentation and the Tysabri Accounting Misrepresentation (both of which are contained in the Amended Roofers Complaint, with the latter wrongful act alone contained in the Keinan Complaint). These four wrongful acts also feature in the Israeli Electric Complaint, which is set out at para 9.97 of the Agreed Statement of Facts. That is a class action against Perrigo taken by its shareholders, who had purchased shares in the Tel Aviv Stock Exchange. That complaint does not have to be directly considered in this case, since the four wrongful acts which form the basis of that complaint feature in the Roofers Complaint and in the Amended Roofers Complaint. Accordingly, whatever conclusion is reached regarding the Roofers Complaint and the Amended Roofers Complaint will determine whether the wrongful acts forming the basis of the Israeli Electric Complaint are aggregated back to the 2014 Policy or not. However, the reason for referring to the Israeli Electric Complaint is because it considers the nature of these four wrongful acts, bearing in mind that it is the nature of those four wrongful acts which have to be compared with the wrongful acts forming the basis of the Mylan Counterclaim, to see if they are similar or related.

82. For this reason, it is helpful to consider how the plaintiffs in the Israeli Electric Complaint classified these four wrongful acts. As noted at para 9.101 of the Agreed Statement of Facts, the plaintiffs in the Israeli Electric Complaint claim that those four wrongful acts are 'inextricably linked'. In the proceedings, they call these four wrongful acts 'avenues' and go on to state that:

"Some of the avenues were created by Perrigo for imaginary and fictional profit forecasts, some concealed the true value of Perrigo's assets, and some created hidden potential liabilities for Perrigo (in the form of fines and return of profits)."

"However, the four avenues together concealed the company's true state from the investors, and presented deceptive and inflated presentations regarding the company's work so that investors would reject Mylan's purchase offer" (Emphasis added)

It seems to this Court that this gets to the very essence of the four wrongful acts of Organic Growth Misrepresentation, Omega Integration Misrepresentation, Collusive Pricing Misrepresentation and Tysabri Accounting Misrepresentation, namely that their essential nature is the wrongful inflating of the true value of the company.

83. Thus, in considering whether wrongful acts (ii) and (iii) in the Roofers Complaint (i.e. Organic Growth Representation and Omega Integration Representation), and later in the judgment, whether the two other wrongful acts (Collusive Pricing Misrepresentation and Tysabri Accounting Misrepresentation), are similar or related to the Mylan Counterclaim wrongful acts, it is helpful to bear in mind that the essence of the nature of these four wrongful acts is inflating the company's value.

Wrongful act (ii) in the Roofers Complaint - Organic Growth Misrepresentation

84. The first one to consider is wrongful act (ii) in the Roofers Complaint (the Organic Growth Misrepresentation), namely that, in order to persuade Perrigo shareholders to reject the Mylan Offer, Perrigo allegedly misrepresented that it would be able to achieve 5%-10% in organic growth as a stand-alone company i.e. without any synergies arising from the takeover by Mylan.

85. The question is whether this Organic Growth Misrepresentation is similar or related to any of the wrongful acts, (i) to (iv) in the Mylan Counterclaim, i.e. the Offer Value Misrepresentation, the Dilutive Misrepresentation, the Abbot Misrepresentation or the Synergy Misrepresentation.

86. It has been observed that, while as a matter of ordinary English, two acts could be regarded as similar or related if they have the same objective, it is important to note that the fact that two sets of wrongful acts are alleged to be for the same purpose (defeating the Mylan Offer) is not a determinative factor in assessing whether wrongful act (ii) in the Roofers Complaint is similar or related to the any of wrongful acts (i) to (iv) of the Mylan Counterclaim. This is because, as already noted, one is dealing with an event clause, not an originating cause clause.

87. Looking therefore at the nature of the acts themselves, it has been noted that the very essence of the Organic Growth Misrepresentation, an allegedly false misrepresentation that a company would achieve a 5%-10% organic growth, could be described as the wrongful act of inflating the company's value. This is its nature irrespective of whether it is to increase its share price or indeed to stave off a takeover.

88. This wrongful act is not, in this Court's view, similar or related to the wrongful acts in the Mylan Counterclaim, i.e. the Offer Value Misrepresentation, the Dilutive Misrepresentation, the Abbot Misrepresentation or the Synergy Misrepresentation. This is because these are all very specific wrongful acts confined to their own very specific facts.

89. Firstly, the Offer Value Misrepresentation is a claim that the premium which the Mylan Offer would give to shareholders was only 14% above Perrigo's unaffected share price. This is very different in nature from a claim that Perrigo will achieve 5%-10% organic growth as a standalone company.

90. Secondly, the Dilutive Misrepresentation claims that the Mylan Offer would have a dilutive, rather than accretive, effect on the earnings per share of Perrigo. This again is a very specific claim and is different in nature from a claim that Perrigo will achieve 5%-10% organic growth as a standalone company.

91. Thirdly, the Abbot Misrepresentation, that Abbot did not support the takeover attempt claim, is even more starkly different in nature from a claim that Perrigo will achieve 5%-10% organic growth as a standalone company. The former wrongful act is a misrepresentation of a third party's state of mind, while the latter wrongful act relates to the financial performance of Perrigo. Bearing in mind how strict the interpretation is given to terms such as similar and related in event aggregation clauses, it is difficult to make any argument that these two wrongful acts are similar or related, particularly when one bears in mind that the purpose of the wrongful acts is not determinative of whether two wrongful acts are similar or related in an event aggregation clause.

92. Fourthly, there is the Synergy Misrepresentation, i.e. that Mylan was wrong to claim that it would achieve the same synergies with Perrigo, whether it was a 100% shareholder or a 50% plus shareholder. This is not sufficiently similar or related to a claim that Perrigo will achieve 5%-10% organic growth as a standalone company (when one bears in mind the strict interpretation of words such as 'similar' or 'related' in an event clause). They deal with two very distinct wrongful acts, the former wrongful act concerns the synergies which a particular company, Mylan, would have with Perrigo, whereas the latter does not deal with the synergies which Perrigo would have with another company, Mylan or any other company. Rather it deals with the distinct issue of what growth Perrigo would achieve as a standalone company.

93. The difference between the Organic Growth Misrepresentation and the wrongful acts in the Mylan Counterclaim becomes even clearer when one considers the caselaw on how 'unifying concepts' in event aggregation clauses (albeit that the unifying concepts in the clauses in those cases is not the same as the unifying concept in Section 5.1(iii)) e.g. the cases, to which reference has been made, to the acts of a solicitor stealing from a client being held not to be sufficiently connected with other acts of that solicitor stealing from a client, so as to be subject to an aggregation clause.

94. For the foregoing reasons therefore, this wrongful act (Organic Growth Misrepresentation) is not similar or related to the wrongful acts in the Mylan Counterclaim and so it does not aggregate back to the 2014 Policy.

Wrongful act (iii) in the Roofers Complaint - Omega Integration Misrepresentation

95. Wrongful act (iii) in the Roofers Complaint is that, in order to persuade Perrigo shareholders to reject the Mylan Offer, it misrepresented that Perrigo was experiencing serious issues integrating the Omega acquisition - the Omega Integration Misrepresentation.

96. The issue is whether this wrongful act is similar or related to any of the wrongful acts in the Mylan Counterclaim, i.e. the Offer Value Misrepresentation, the Dilutive Misrepresentation, the Abbot Misrepresentation or the Synergy Misrepresentation.

97. As with wrongful act (ii) in the Roofers Complaint, looking at the nature of this wrongful act (iii), it seems to this Court that a representation that Perrigo was not experiencing serious issues integrating the Omega acquisition (when it allegedly was) can be described, as the wrongful act of inflating the company's value, irrespective of the purpose, e.g. whether to increase its share price or defeat the Mylan Offer.

98. This is a very fact specific wrongful act, relating as it does to the integration of the Omega acquisition into the business of Perrigo. For the purposes of a comparison this Omega Integration Misrepresentation with the wrongful acts in the Mylan Counterclaim, the relevant details of the Offer Value Misrepresentation, the Dilutive Misrepresentation, the Abbot Misrepresentation or the Synergy Misrepresentation have already been set out (when dealing with the Organic Growth Misrepresentation). It is not proposed to set them out again and for very similar reasons to those outlined in relation to the Organic Growth Misrepresentation, which it is not proposed to repeat, this very fact specific wrongful act of Omega Integration Misrepresentation (that Perrigo was not experiencing difficulties integrating Omega into its business, when it allegedly was) is not similar or related to any of these four wrongful acts in the Mylan Counterclaim.

99. Accordingly, this wrongful act (Omega Integration Misrepresentation) does not aggregate back to the 2014 Policy.

Splicing of wrongful acts to different policy periods

100. One of the arguments made by Chubb against aggregating wrongful acts back to the 2014 Policy was that it might lead to a 'splicing' of wrongful acts in a claim between different policies. Because of this Court's conclusion that wrongful act (i) in the Roofers Complaint is aggregated back to the 2014 Policy, while wrongful acts (ii) and (iii) are not, this is exactly what is happening. However, it was suggested, on behalf of Chubb in its written submissionsat para 47, that it is wrong to 'splice' the wrongful acts in a claim between different policy periods, as the claim as a whole should attach to a particular policy period.

101. It is this Court's view that once again the language of the aggregation clause is critical, and in this regard, the reference in that clause is to wrongful acts, not to 'claims' or 'complaints' or 'court proceedings' being deemed to be covered by a particular policy period. On this basis, this Court cannot see any basis for the suggestion that a claim or proceedings cannot be spliced between different policy periods, in the sense that some wrongful acts are covered by one policy and other wrongful acts are covered by a different policy.

102. Although not determinative, but nonetheless in support of this conclusion is the fact that in practice Chubb appears to engage in 'splicing' of claims. This is because one issue which this Court did not have to consider was one of the five wrongful acts contained in the 2019 Derivative Complaint, namely the Tysabri Tax Liability Claim. The other four wrongful acts in the 2019 Derivative Complaint are the Omega Integration Representation and the Organic Growth Misrepresentation, which are the same as wrongful acts (ii) and (iii) in the Roofers Complaint, and the Collusion Pricing Misrepresentation and the Tysabri Accounting Misrepresentation, which are the same as the wrongful acts (iii) and (iv) in the Amended Roofers Complaint. This Court must decide whether those four wrongful acts aggregate back to the 2014 Policy.