Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

The Law Commission

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> The Law Commission >> Regulating Coal Tip Safety in Wales [2022] EWLC 406 (23 March 2022)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/ew/other/EWLC/2022/LC406.html

Cite as: [2022] EWLC 406

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

Reforming the law

Law Com No 406

Regulating Coal Tip Safety in

Wales: Report

Presented to the Senedd 23 March 2022

© Crown copyright 2022

This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: mpsi@nationalarchives.gsi.gov.uk.

Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned.

This publication is available at www.gov.uk/government/publications.

The Law Commission

The Law Commission was set up by the Law Commissions Act 1965 for the purpose of promoting the reform of the law.

The Law Commissioners are:

The Right Honourable Lord Justice Nicholas Green, Chair

Professor Sarah Green

Professor Nick Hopkins

Professor Penney Lewis

Nicholas Paines QC

The Chief Executive of the Law Commission is Phil Golding.

The Law Commission is located at 1st Floor, Tower, 52 Queen Anne’s Gate, London SW1H 9AG.

The terms of this report were agreed on 24 February 2022.

The text of this report is available on the Law Commission’s website at

http://www.lawcom.gov.uk/project/regulating-coal-tip-safety-in-wales/.

Contents

Provisional proposals and consultation

Outline of this report and our recommendations

The scope of our recommendations: tips associated with operational mines 9

The case for a single supervisory body for disused tips

An existing or newly created body?

The duty of the supervisory authority to ensure the safety of disused coal

Should a tip register be compiled and maintained?

Prescribing the contents of the tip register

Entry of a tip on the register

Should the information on the tip register be publicly accessible?

MANAGEMENT PLANS AND RISK CLASSIFICATIONS

Risk assessment, tip management plans and risk classification

Approaches to risk classification

Consequences of classification: agreements and orders

Monitoring compliance with tip maintenance agreements

Responsibility for tip maintenance agreements and orders

Tip designation as a way of prioritising tips

Right of appeal against designation

Responsibility for work on designated tips

Enforcement powers and offences

Claims for compensation or contribution

A wider emergency power under the Environmental Permitting Regulations 184

Glossary

Abandoned tip: Under the Mines Regulations 2014, an abandoned tip is a tip associated with a mine that has been abandoned. It becomes an abandoned tip from the date of a notice of abandonment of the mine, after which the 2014 Regulations cease to apply. See also Disused tip.

Active tip: Under the Mines and Quarries (Tips) Act 1969, an active tip is a tip associated with an active mine or quarry.

Adit: A horizontal or sloping passage leading into a mine.

Attenuation pond: A pond which acts as a silt trap allowing any suspended sediment within the surface water to settle out (a process called attenuation). The accumulated sediment has to be routinely removed to ensure that the pond remains effective.

British Coal Corporation: Successor of the National Coal Board, set up under Coal Industry Act 1987, and commonly known as British Coal. Succeeded by the Coal Authority.

Cavitational collapse: A localised collapse of underground voids resulting from events such as piping failures, collapsed culverts or underground combustion. General tip stability is not usually affected, except sometimes in the case of lagoon embankments, although sudden collapse may be a source of danger to life if anyone is at the surface.

Coal Authority: The Coal Authority is an executive non-departmental public body, sponsored by the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS), a UK Government department. It was established under the Coal Industry Act 1994 and manages the effects of past coal mining, including subsidence damage and mine water pollution.

Coal Tip Safety Task Force: Formed by the Welsh Government immediately following the Tylorstown slide on 16 February 2020. The Task Force’s purpose is to deliver an urgent programme of work to ensure that coal tips across Wales are being managed safely and effectively. The Task Force is led by the Department for Environment and Rural Affairs, a Welsh Government department. Task Force partners working together with the Welsh Government are the Coal Authority, its sponsoring body the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, and the Welsh Office. The technical group working with the Task Force includes Natural Resources Wales, local authorities and the Welsh Local Government Association.

Coal waste: The unwanted material produced after saleable coal is separated out from the material extracted from a coal mine in a process of washing and preparation. The material is predominantly shale but also includes other discarded material. The waste is known as refuse in the wider mining industry, and more commonly ‘spoil’ in coal mining.

Colliery: A coal mine and the buildings and equipment associated with it.

Disused tip: A tip which is no longer being tipped upon and is not associated with an operational mine.

Factor of safety: The factor of safety of a tip is equal to the ratio of resisting forces to disturbing forces: the higher the factor, the safer the tip. If the factor is below one, in other words less than unity, the disturbing forces are stronger than the resisting forces.

Large raised reservoir: In Wales, a large raised reservoir is a reservoir that holds or has the potential to hold 10,000 cubic metres of water above ground level.

Maintenance: Routine tip maintenance includes the clearing out, re-cutting and improvement of drainage ditches and culverts, and checking and clearing screens designed to capture detritus after heavy rainfall.

MS: Member of the Senedd. The equivalent in Welsh is AS.

Opencast mining: A mining technique that involves taking minerals, especially coal, from the surface of the ground rather than from passages dug under it.

Overburden: Material composed mainly of rock and soil which is removed in order to access a coal seam or other mineral deposit to make it ready for mining.

Receptors: A feature that could be impacted by a coal tip slide (such as a house, school or road).

Reclamation: The process by which derelict, despoiled or contaminated land is brought back into a specified beneficial use.

Remediation: The process by which health and safety and environmental risks are reduced to an acceptable level. The aim of coal tip remediation is to ensure the safety of coal tips.

Restoration bond: A bond provided by a mining company prior to beginning a mining operation for the purpose of remediation upon the cessation of the mining activity.

Senedd: The democratically elected body which makes legislation for Wales (within certain subject areas). It is known both as the Welsh Parliament and the Senedd Cymru. In this report we refer to it by its commonly used Welsh name, the Senedd.

Slurry: A mixture of solids denser than water suspended in liquid.

Spoil: See Coal waste.

SSSI: Site of Special Scientific Interest, a conservation designation.

Surface mining: See Opencast mining.

Tailings lagoon: A lagoon into which tailings are placed.

Tailings: A mixture of fine mineral particles and water left after the coal washing process.

Task Force: See Coal Tip Safety Task Force.

Tip: A pile built of accumulated waste material removed during mining. In the case of a coal tip, this is the accumulated material which remains after saleable coal has been separated from the unwanted material with which it has been extracted.

Websites

All websites referenced in this document were last visited on 22 March 2022.

viii

-

1.1 The first legislation to provide for the safety and stability of mineral waste in the UK, the Mines and Quarries (Tips) Act 1969, was enacted in response to the Aberfan disaster in South Wales in October 1966, when a coal tip slide engulfed a row of houses and a school, killing 28 adults and 116 children. The Act was passed in the days of an active coal mining industry and was primarily designed to regulate the tipping of waste from active coal mines, as well as mines and quarries associated with the extraction of other minerals. Though Part 2 of the Act made provision for tips left behind by abandoned mine and quarry workings (referred to in the Act and in this report as “disused tips”), its designers regarded such tips as being typically those dating from earlier, smaller scale mining operations and a lesser problem.

-

1.2 Part 2 of the 1969 Act is still in force, but no longer provides an effective management framework for disused coal tips in the twenty-first century. In Wales today almost all coal tips are disused.

-

1.3 The Aberfan disaster was precipitated by heavy rainfall. Fifty-three years later, in February 2020, unprecedented levels of rainfall in South Wales precipitated another coal tip slide only a few miles from Aberfan, when an estimated 60,000 tonnes of coal tip waste slipped down the Llanwonno hillside at Tylorstown in the Rhondda.1 Fortunately, owing to the tip being on the opposite side of the Rhondda Fach river from the village, no homes were destroyed or human lives lost. The slide nevertheless blocked the river, buried a water main and broke a sewer. The immediate clearance work cost £2.5 million and the total cost of dealing permanently with the displaced colliery waste is now estimated at some £13 million.

-

1.4 Wales has nearly 2,500 coal tips. 2The vast majority of them are not a hazard. Many can be kept safe by maintenance of the tip’s drainage system, as proper drainage prevents the waste from becoming saturated and unstable. 3A few are likely to require more major work. Immediately following the Tylorstown slide, the Welsh Government instituted a coal tip safety work programme to be delivered by the Coal Tip Safety Task Force. This is designed to take stock of Wales’s legacy of coal mining tips and ensure that tips across Wales are managed safely and effectively. Urgent safety work has included data gathering on all tips, including location, risk category and ownership type, and walkover inspections of all higher risk tips. The inspections identified the maintenance and remediation work needed, with recommended timescales for completion.4

-

1.5 As part of its response to the Tylorstown emergency, the Welsh Government asked the Law Commission to undertake an independent review of the coal tips safety legislation and make recommendations for its reform. Our project formally commenced on 2 November 2020.

TERMS OF REFERENCE

-

1.6 Our agreed terms of reference are:

-

(1) to review the law governing coal tips in Wales and consider options for a modern legislative framework, in line with Wales’s existing legislation, including the Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015 and Environment (Wales) Act 2016, for regulating their safety; and

-

(2) to recommend a coherent, standardised and future-proofed system for identifying, recording, inspecting and maintaining coal tips throughout their lifecycle, identifying an overarching set of duties and adopting a uniform approach to risk assessment.

-

1.7 It was agreed in particular that the project would:

-

(1) consider the current ownership and management of coal tips in Wales, drawing on the work of the Coal Tip Safety Task Force as needed;

-

(2) evaluate current legislation relating to the safety of coal tips, from the perspective of human health and safety and of environmental impact, identifying gaps, inconsistencies and approaches which are unhelpful or have become outdated;

-

(3) identify options for alternative regulatory models to be adopted in Wales;

-

(4) identify the features needed to ensure that any proposed system is able to provide effective enforcement, and in particular a rapid and coordinated response when emergency works become necessary;

-

(5) consider how other nations of the UK, and other countries with a significant history of coal mining, particularly in the EU, approach coal tip safety, where these provide useful comparison and to the extent that such information is readily available; and

-

(6) consider the impact of EU law and the effect on the existing regulatory framework of leaving the EU.

-

1.8 It was agreed that the project would be conducted in an expedited timescale of 13 to 15 months. As the project would be running alongside the coal tip safety work conducted by the Welsh Government and the Coal Tip Safety Task Force to mitigate the immediate risk posed by coal tips in Wales, three express limitations on the project were also recognised.

-

(1) The project would focus on systematic, long-term legislation to tackle the safety risk posed by coal tips.

-

(2) The project would focus on the law governing coal tips only.

-

(3) The project would not review wider environmental law concerns except insofar

as they were directly relevant to regulating the safety risk posed by coal tips.

-

1.9 Our terms of reference do not - and could not - extend to the issue of how the cost of the work required on coal tips should be funded. We are aware that in some cases, of which the cost of dealing with the Tylorstown slide is an example, the cost can be considerable. We are also aware of discussions between the Welsh and United Kingdom Governments on the issue of how any required public funding should be provided. A number of consultation responses touched on the question of the extent to which the costs associated with coal tips should be borne by public funds or - as is the general position under the current legislation - by the owners of tips, who are themselves a mixture of public bodies and private owners.

-

1.10 It would be wrong for us to make any recommendation or express any view on these issues. Instead we have designed a scheme that incorporates the flexibility to allocate costs in accordance with a policy to be devised by the Welsh Government.

PROVISIONAL PROPOSALS AND CONSULTATION

-

1.11 Our consultation paper, published on 9 June 2021, reviewed coal tip safety law and the problems encountered in the current management of disused tips. Our preliminary research revealed a number of shortcomings in the current legal framework. The 1969 Act left responsibility for disused tips to local authorities but gave them only limited powers of intervention, confined to situations where there was perceived to be an existing risk to the public by reason of a tip having become unstable. Its mechanisms for requiring owners to carry out remedial work were cumbersome and timeconsuming. The alternative that it provided, for the local authority to do the work and charge the owner, was also unwieldy. The fragmentation of powers across local authorities led to inconsistent safety standards and risk classifications.

-

1.12 We also found gaps in the provision made by the 1969 Act. It did not create a general duty to ensure the safety of coal tips, nor provide a power to require or undertake preventive maintenance to prevent a tip becoming a danger. It did not cover hazards other than instability. There was no central point of responsibility and thus no overarching mechanism to prioritise tips on the basis of risk.5

-

1.13 There were other difficulties which did not stem from the provisions of the 1969 Act, but which impacted on its operation. Loss of specialism resulting from the virtual cessation of coal mining in Wales, together with limitations on resources, were constraining local authorities’ capacity to exercise their powers. The sustained and impressive tip remediation work carried out in the decades following the Aberfan disaster in 1966, in particular the Land Reclamation Programme, had come to an end by 2012.6

-

1.14 We looked at the reasons why these deficiencies had become more significant in current circumstances. As explained above, almost all the coal mines that were operational at the time that the 1969 Act was passed have closed, and their tips have moved into the residual category governed by Part 2 of the Act. About 65% of these are in private ownership, owned by landowners with, generally, no connection with the mining industry, no vested or economic interest in the maintenance of tips, and no skill or knowledge concerning their care. In addition, rainfall has increased significantly due to climate change. This increases the risk of instability, particularly if drainage issues affecting a tip are not addressed.

-

1.15 We provisionally concluded that the regime created by the 1969 Act was no longer adequate and needed to be replaced by a new regulatory regime. A new regime could also address other problems not arising from the Act itself, by providing efficiencies of scale and addressing the shortfall in specialist skills.

-

1.16 We identified two principles that we thought should govern its construction: consistency of approach and the prevention of harm through a proactive rather than reactive approach. In our view, these principles align well with the sustainable development principle set out in the Environment (Wales) Act 2016 and the requirement in the Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015 to act in accordance with this principle. The sustainable development principle requires a public body to take account of the long term, to take action which helps to prevent problems occurring, and to take an integrated approach.

-

1.17 We also proposed that the new framework should be capable of expansion to cover risks going beyond instability. It would need to be sufficiently robust to deal with the implications of climate change, and sufficiently flexible to work in tandem with other legislation providing environmental protection. As the 1969 Act covers all tips, not simply coal tips, we anticipated that its replacement might come to be extended to non-coal tips and should have a structure which would permit this.

-

1.18 We presented a number of provisional proposals for the new regulatory regime. Our consultation questions asked for views on these proposals. We also asked a number of open questions where we were not sufficiently sure of our preferred approach to make a provisional proposal.

-

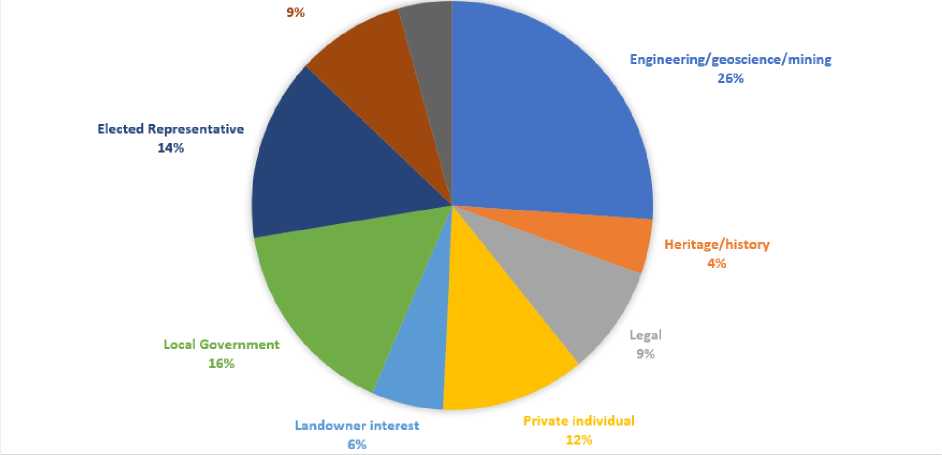

1.19 Following publication of the consultation paper, we held a series of consultation events. These are listed in appendix 1 to this report. Consultation closed on 10 September 2021. The stakeholders who responded to our consultation are listed at appendix 2, together with an indication of the sector they represent and a chart illustrating the proportion of responses received from each sector. All responses to the consultation, save those for which confidentiality was requested, and our consultation analysis are available on the Law Commission website. The consultation analysis presents a table of the responses to each consultation question. It also explains our methodology in conducting the analysis. In some cases, we re-categorised the “yes”, “no” or “other” responses to ensure that views which were similar in content were grouped together. We have marked the analysis tables to show where this has been done.

OUTLINE OF THIS REPORT AND OUR RECOMMENDATIONS

-

1.20 Our first task is to decide the scope of our recommendations: our terms of reference extend to all coal tips in Wales, raising the question of whether law reform should extend also to the very small number of tips that are associated with active mining operations. We discuss this in the final part of this chapter, where we conclude that the existing regime for active tips is satisfactory and should not be disturbed.

-

1.21 For disused tips we recommend a new safety regime that builds upon the work done in the last two years by the Coal Tip Safety Task Force. We recommend first that the Wales-wide remit of the Task Force should pass to a newly created coal tip supervisory authority, whose precise legal form we leave it to the Welsh Government to determine; we refer to it throughout this report as “the supervisory authority”.

-

1.22 The supervisory authority’s first task should be to compile a statutory register of coal tips, which in practice will be based on the inventory of tips compiled by the Task Force. Its second task will be to arrange for an inspection of each tip, unless it considers that a sufficiently recent and thorough inspection has already been done. On the basis of that inspection, it must arrange for the compilation of a risk assessment and tip management plan, and assign a risk classification to each tip. The risk classification should be based on criteria set by the Welsh Government with input by technical experts, and should include a system for designation of those tips that require priority remediation work; this work should generally be carried out by the supervisory authority itself. Given that the majority of tips are low risk, most of the inspections will not need to be intensive.

-

1.23 As regards authorising or requiring the carrying out of work on tips, it has been necessary to devise mechanisms that are flexible enough to cater for the full range of tips. This encompasses the great majority that only require monitoring, or basic maintenance that is within the capacity of the landowner, as well as the small minority that require more sophisticated work, possibly as a matter of urgency. Consultation has confirmed our provisional view that these mechanisms should take the form of a power to make agreements with owners and/or occupiers of land containing a tip, backed by a power to make an order if an agreement is not reached or not complied with, or in a situation of emergency.

-

1.24 Such agreements or orders may either require the carrying out of work by an owner or occupier of the land or authorise its carrying out by an authority. They will also contain financial provisions regarding payments to or by the authority and to or by any person who is a party to an agreement or named in an order. This is designed to obviate the need for the complex systems contained in the 1969 Act for compensation and contributions to tip management costs as between people with an interest in the tip. It is also designed to accommodate any future decisions by the Welsh Government on the financing of tip safety work. We recommend a right of appeal against the terms of a tip order, including its financial terms.

-

1.25 Another issue that we regard as organisational rather than legal, and ultimately for determination by the Welsh Government, is how the tasks associated with coal tip safety might be distributed between the new supervisory authority and the local authorities that have exclusive responsibility at present. We consider it important, in the interests of a fully informed and consistent approach, that some of the tasks be performed by the supervisory authority itself. Reviewing initial inspections of tips and determining their risk classification fall into this category, as do entering formally into tip agreements and making tip orders and, for the most part, carrying out work on designated priority tips.

-

1.26 The associated field work - such as inspecting tips, monitoring compliance with agreements and orders, and conceivably negotiating and/or drafting agreements and orders - will in principle have the same cost whoever carries it out. But we can see some potential for efficiencies in delegating some of these tasks to local authority personnel located in proximity to the tips. We are at the same time conscious of concerns expressed to us by local authorities that any such delegation of tasks will need to be accompanied by adequate funding.

-

1.27 The paragraphs that follow expand on this brief summary with a survey of the chapters of this report which examine the responses to our consultation questions and set out our recommendations.

-

1.28 In chapter 2, we evaluate responses to our proposal for a single supervisory authority which is able to monitor all disused tips and ensure compliance with regulatory requirements to a consistent standard across Wales. We recommend that a supervisory authority should be established and that it should be subject to a general duty to perform its functions so as to ensure the safety of disused coal tips. We recommend that the supervisory authority should be a new, central public body.

-

1.29 Chapter 3 looks at our proposal for a central tip register providing information about each tip. We recommend that such a register should be compiled and maintained by the supervisory authority, with its contents prescribed by statutory instrument. We also recommend a duty on the part of the supervisory authority to include on the register any tip of which it is aware, with a right of appeal against registration. In order to ensure that all tips are captured on the register, we recommend that landowners should be under a duty to notify the supervisory authority of any tip situated on their land which is not already on the register. We recommend that there should be public access to the tip register.

-

1.30 Chapters 4, 5 and 6 look in more detail at the functions of the new supervisory authority. Chapter 4 considers our proposal for a duty to inspect every disused tip for the purpose of a risk assessment and the preparation of a tip management plan. We recommend that, upon the entry of a tip onto the register, the supervisory authority should be under a duty to arrange an inspection of the tip unless it considers that a sufficiently recent and thorough inspection has been conducted.

-

1.31 We also recommend that the supervisory authority should be under a duty to arrange for the compilation of a risk assessment and tip management plan for any tip included on the register and to allocate a risk classification to the tip based on the information submitted to it. We conclude that risk classification should have regard to the risk of tip instability and the consequences of such failure, and to risks of pollution, combustion and flooding. We recommend that the Welsh Ministers should have power to prescribe the matters to be included in a risk assessment and tip management plan by statutory instrument.

-

1.32 We explain that, once the tip inspection, risk assessment and tip management plan have been concluded and a risk classification assigned, the supervisory authority will need to make decisions as to how the work identified in the tip management plan is to be carried out. We envisage that the supervisory authority will have a toolkit of agreements and orders with which to organise the safety work specified in the tip management plan. We consider it desirable that tip safety work should in principle be a matter of agreement; the existence of the order-making power should act as a spur to sensible negotiation.

-

1.33 Chapter 5 considers how the maintenance of lower risk tips would be secured. It looks at our proposal for a system of tip maintenance agreements with tip owners in order to ensure that proactive maintenance work and less complex remedial tasks are carried out on lower risk tips. We recommend that the supervisory authority should be empowered to enter into a tip agreement with the owner and/or occupier of land registered in the tip register, providing for the carrying out of the operations specified in the tip management plan.

-

1.34 In order to monitor compliance with such an agreement, we recommend that there should be a duty of periodical inspection of tip sites, with a power to delegate the inspection, including to suitably qualified third parties. Where it is not possible or appropriate to proceed by way of agreement with the owner or occupier, we recommend that a tip order may be made; we set out the circumstances in which we recommend that the order-making power may be exercised. We recommend that responsibility for making tip agreements and orders for lower risk tips should lie with the supervisory authority, and a duty to supervise agreements and orders, including to carry out inspections, should fall to local authorities.

-

1.35 In chapter 6, we look at the need for a process, forming part of the risk assessment and classification, to prioritise work on tips in a systematic way. This builds on our proposal for the designation of tips requiring more immediate and complex work in order to secure increased involvement of the supervisory authority. We recommend that coal tip safety legislation should provide for the designation of a tip by the supervisory authority, and that the criteria for designation should be determined in consultation with experts. We recommend that these criteria be prescribed by the Welsh Ministers by statutory instrument. Where a tip is designated, we recommend that the supervisory authority should normally be under a duty to carry out the operations specified in the tip management plan itself, though it may do so by engaging contractors. While this should be the presumption where a tip is designated, we also recommend that the supervisory authority should have power, where appropriate, to reach agreement with a suitably qualified tip owner or occupier for them to perform or commission the work.

-

1.36 Chapter 7 considers the definition of a tip and of a tip owner. We examine the elements of a satisfactory definition of a disused coal tip, although we do not make a formal recommendation as to how this should be drafted. We conclude that it is not helpful to have a single, exclusive definition of “the tip owner”. Various people having a connection to land containing a tip will need to have rights, duties or obligations under our recommended scheme. Who they are will depend on the pattern of interests in the land and the purpose of the particular right or duty in question. To the extent that liability under our recommended scheme rests with the owner, in economic terms, of land containing a coal tip, we recommend that that owner should be regarded as the owner of the freehold estate or the owner of a leasehold estate of 21 or more years. The exception to this should be where the freehold or leasehold estate is subject to a lease granted to someone else for 21 or more years.

-

1.37 In chapter 8 we look at the enforcement powers needed to ensure that the new regime works effectively. We also look at options for avenues of appeal where the new regime creates a right of appeal. We recommend a power of entry onto land, in terms that secure an appropriate balance between the public interest and the rights of the owner or occupier. In relation to the enforcement of tip orders, we recommend that failure to comply with a tip order should be a summary offence, and suggest that the Welsh Government could also give consideration to the use of civil sanctions.

-

1.38 Chapter 9 considers the need for a power to charge for coal tip safety work, and whether the existing framework of applications to a court for compensation and contribution orders should be retained. Our views on this are influenced first by our conclusion that tip safety work should proceed by way of agreements between the supervisory authority and owners and occupiers, backed up with a power to make an order; secondly, current procedures are cumbersome and rarely if ever used.

-

1.39 We suggest that, instead of the existing system of applications, the terms of agreements and orders should extend to making financial provision as between public funds and any party with an interest in a tip site or its contents. There should be a power to charge for works or to pay for works and to allocate any charges or payments appropriately. We recommend that principles governing the allocation of financial responsibility for tip safety work between persons or entities in the public and private sectors should be laid down by the Welsh Ministers by statutory instrument.

-

1.40 Chapter 10 considers our provisional proposal for a specialist panel of engineers to inspect tips and supervise operations on them. We conclude that a less formal system than a panel would be appropriate, encompassing a range of professional skills in addition to engineering. We recommend that the Welsh Government enters into discussions with academic institutions and professional bodies in the field of tip safety work with a view to securing compilation of a register of professionals competent to undertake tip safety work.

-

1.41 In chapter 11 we look at ways to resolve clashes between tip safety responsibilities and environmental legislation. We recommend that the Welsh Ministers should have a power to give directions to the supervisory authority and other relevant parties regarding actions to be taken in response to a coal tip emergency. This could possibly be accompanied by provision to ensure that there is a lawful basis for actions which might otherwise breach planning or environmental regulations. We also recommend an amendment to the Environmental Permitting Regulations 2016 to define an emergency in the context of tip material. We look at broader strategies to improve responses to tip emergencies as well as longer-term solutions for tip material displaced by remedial works. We do not make recommendations on these, but convey respondents’ suggestions in order to assist with policy development.

-

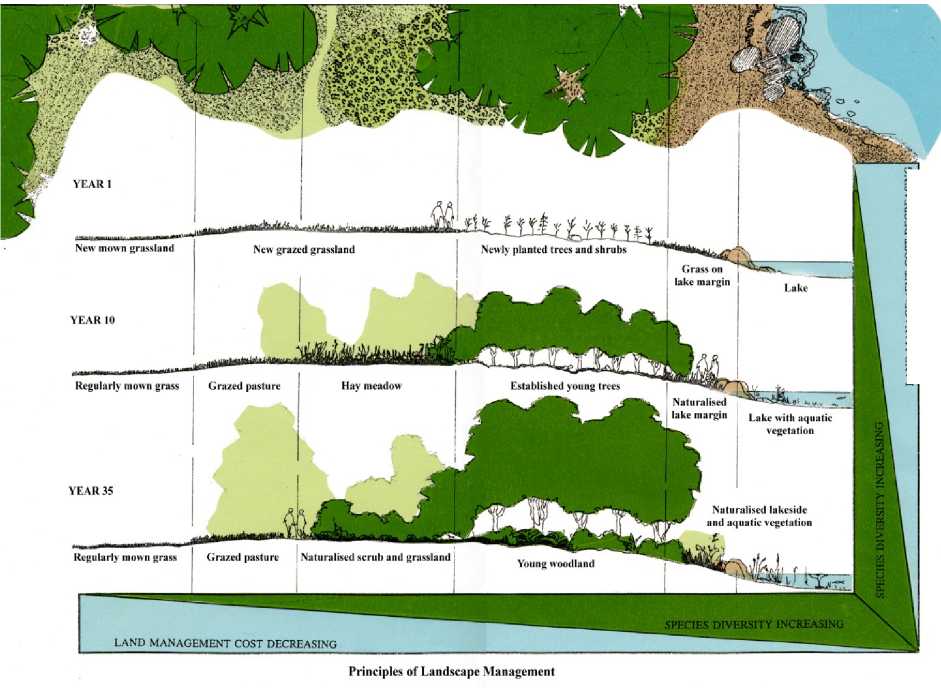

1.42 Chapter 12 considers a wide range of suggestions for how our proposed tip safety regime could be combined with longer-term tip reclamation work in order to bring selected tips into beneficial use. Once again, we do not make recommendations, as the topic falls outside our terms of reference, but invite the Welsh Government to consider respondents’ views as to the most appropriate models for reclamation initiatives, the heritage and biodiversity value of tips, and ideas for beneficial uses for reclaimed tips. Finally we take a look at the potential to extend the new regulatory framework to non-coal tips.

-

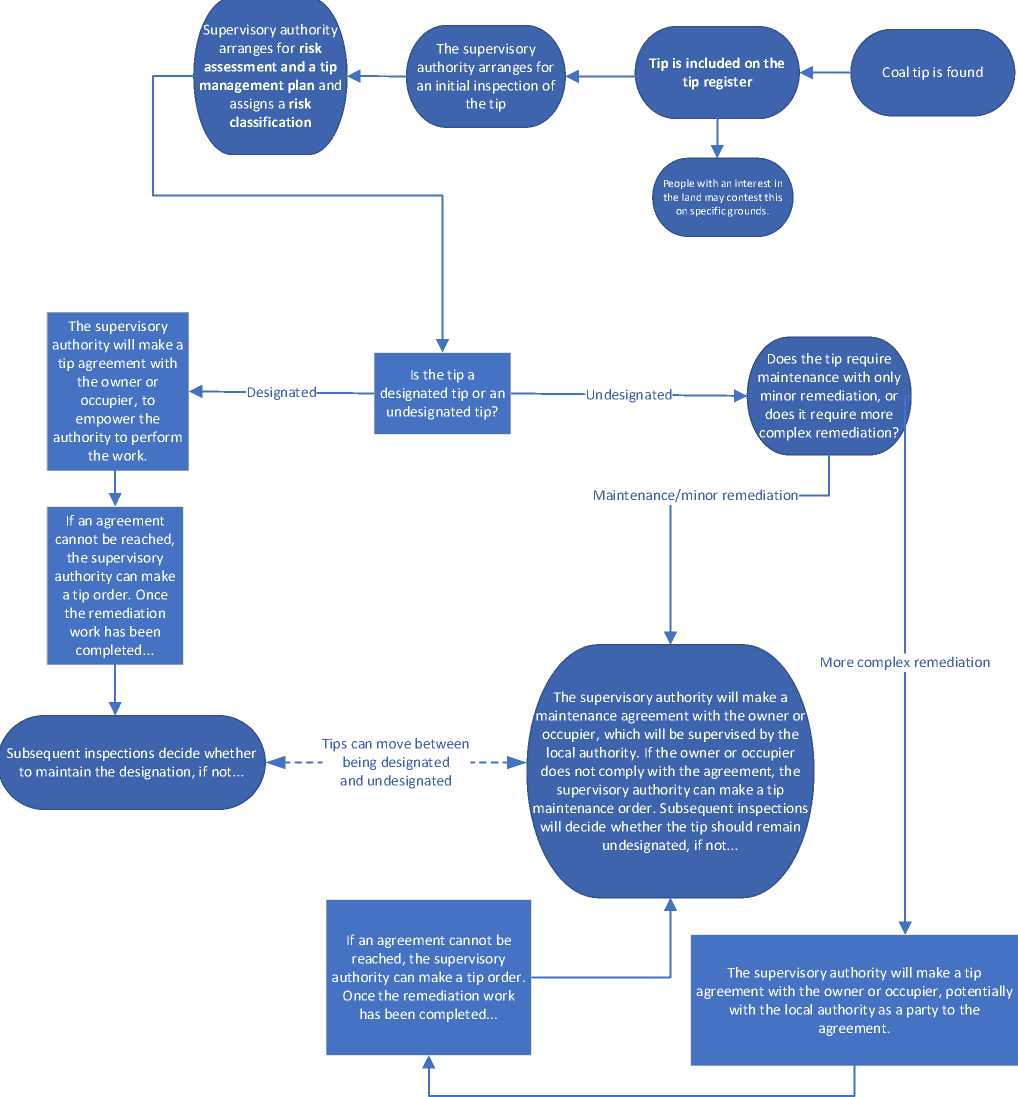

1.43 A diagram illustrating the way in which we envisage that the new regulatory framework will work is provided in appendix 3 to this report.

GLOSSARY

-

1.44 There is a glossary of technical terms at the beginning of this report.

IMPACT ASSESSMENT

-

1.45 An impact assessment and Welsh Language assessment accompanies this report. The impact assessment considers the potential costs and benefits of a new regulatory regime for disused coal tips. We are grateful to the Welsh Government for their assistance with the preparation of the assessment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

-

1.46 Our thanks go to all those who took part in the consultation process, both for participating in consultation events or meeting with us to discuss the consultation paper, and for submitting formal written responses. We are grateful for the care with which they have considered the issues covered in this report. We also thank officials from the Welsh Government who have hosted workshops to help us to understand the current tip safety system and to test our ideas for a new regulatory framework.

PROJECT TEAM

-

1.47 The following members of the Public Law and Law in Wales team have contributed to this report: Henni Ouahes (team manager), Sarah Smith (acting team manager), Lisa Smith (team lawyer) and Poppy Jones (research assistant).

THE SCOPE OF OUR RECOMMENDATIONS: TIPS ASSOCIATED WITH OPERATIONAL MINES

-

1.48 Before embarking on consideration of each element of the proposed framework, it is necessary to determine an important issue of scope: whether our recommendations should encompass tips associated with operational mines as well as disused tips.

-

1.49 We had been told by stakeholders during the pre-consultation phase of our project that the existing regulatory regime for tips associated with operational mines, under the Quarries Regulations 19997 and the Mines Regulations 20148, was comprehensive and adequate. In our consultation paper we noted that there were areas of concern relating to conditions governing the closure of mines and the remediation of tips, but that these were to do with the operation of available controls rather than the existing legal framework. There are also very few such tips remaining in Wales.9

-

1.50 The regime for tips associated with active mines and quarries is designed for tips which remain under the control of a mine operator. The mining and tipping operations are subject to the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974. The position of disused tips is clearly distinct from the regulation of tipping. The provisional view expressed in our consultation paper was that disused tips require a separate regime tailored to the circumstances of tips that, by and large, are not on land owned or controlled by a body with mining or environmental expertise. We provisionally proposed that the existing regulatory regime for operational tips should not be altered.

-

1.51 We also noted that the 1969 Act defines a disused tip as a tip other than one to which the 1999 or 2014 Regulations apply. We provisionally proposed that, as at present, the new legislation should be expressed not to apply to tips to which these Regulations apply.

-

1.52 The sections below consider views on each of these proposals.

Consultation Question 1: We provisionally propose that the existing regulatory regime for tips associated with operational mines should not be altered. Do you agree?

-

1.53 Of the 43 respondents who answered this question, 38 (88%) agreed and four (9%) disagreed. One respondent answered “other”.

Reasons for agreeing that the regulatory regime should not be altered

-

1.54 Many of those respondents agreeing with our proposal, including Bob Leeming, Howard Siddle, ICE Wales Cymru, Professor David Petley, Kim Moreton and Lee Jones, did so on the ground that the existing regime for tips associated with operational mines was adequate and was not in need of amendment. Jane Iwanicki observed that this regime extended beyond the 1999 and 2014 Regulations:

There is an existing robust and modern system in place for the regulation of tips associated with operational mines, which is further supported and enforced by the Town and Country Planning system and environmental/pollution prevention and control legislation. A similarly robust system will have applied to mines/tips closing in recent years.

-

1.55 Professor Bob Lee agreed that failures of regulation, for example as to financial provision for the aftercare of tips, have been operational. In principle, in his view, if properly administered, the requirements of planning law, environmental permitting and mining law provisions ought to be adequate to make long-term provision for mining waste.

-

1.56 Keith Bush QC noted that it would be a complex task to ensure consistency between a new regime for tips associated with operational mines and the legal framework relating to the safety of operational mines in general.

-

1.57 ICE Wales Cymru, while agreeing with our proposal, thought that tips associated with operational mines should still be listed on the tip register and categorised as “active” with links to key data. This would make their subsequent inclusion on the register as a disused tip much easier.

Reasons for disagreeing

-

1.58 The Coal Action Network did not agree that concerns relating to the closure and remediation of operational coal mines related purely to practice rather than to the regulatory framework. They referred to Celtic Energy's sale of land rights and liabilities at Margam, East Pit, and two other mines to a shell company; this was found to be lawful under the current regulatory framework, despite recognition that it could be viewed as dishonest:10

It is not possible to exclude the possibility, therefore, that operational coal mines will do likewise depending on the specific conditions around how and when the restoration bond is paid. Thus, parts of any future regulatory regime should apply to currently operational coal mines where this may prevent actions ... that compromise the financial resources required to make safe and restore currently operational coal mines and associated coal tips.

-

1.59 Steve Harford disagreed on the ground that “the experience of managing and monitoring old spoil tips could provide important learning for the management of an active tip”.

-

1.60 Owen Jordan thought that the regime for tips associated with active mines needs to be altered to require all tips to be capped and lined on environmental grounds. He thought that the best way to do this was to require all the tip material to be put back “into the hole it came out of”.

Consultation Question 3: We provisionally propose that any new legislation should not apply to a tip to which the Quarries Regulations 1999 or the Mines Regulations 2014 apply. Do you agree?

-

1.61 Of the 41 who answered this question, 32 (78%) agreed, seven (17%) disagreed and two responded “other”.

Reasons for agreeing that any new legislation should not apply

-

1.62 Many respondents referred to their answers to the question above to repeat that the provisions for working mines and quarries were adequate. They agreed that the issues posed by disused tips were quite different from those relating to operational mining. The Mineral Products Association considered it “imperative that the two regimes remain separate and distinct”. Howard Siddle noted that these differences were recognised by their different treatment under Parts 1 and 2 of the 1969 Act.

-

1.63 Keith Bush QC also observed that legislating for tips associated with operational mines was likely to be outside the legislative competence of the Senedd as it would relate to "coal, including - deep and opencast coal mining", and to "the subject-matter of Part 1 of the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974" under the Government of Wales Act 2006.11

Reasons for disagreeing

-

1.64 Some respondents, such as Steve Harford and Vikki Howells MS, thought that the best way to ensure safety was for the new regulatory regime to apply to all tips. Philip Thomas saw an opportunity to preserve uniformity of treatment if a private landowner owned both disused and active mining operations. Owen Jordan saw any division in regulation as providing an opportunity for both owners and regulators to avoid responsibility.

Other observations

-

1.65 Rhondda Cynon Taf did not agree or disagree with our proposal, but asked whether the proposed legislation would involve repealing the 1969 Act, noting that the legislation applies to both England and Wales. They also wanted to know if the new regulatory regime would be introduced by way of primary legislation or as secondary legislation amending the 1969 Act. Their members were keen to ensure that the new legislation captured the coal mining legacy in Wales, and that the disproportionate impact of this legacy on Rhondda Cynon Taf and Wales should be recognised by the UK Government.

Discussion

-

1.66 Respondents gave compelling reasons for supporting our provisional proposals. We agree that cooperation between those responsible for securing disused coal tip safety and those with expertise in managing tips associated with active mines is valuable and should be encouraged. But we do not think that this is a sufficiently strong reason to merge the two regimes. We maintain our view that conditions governing the closure of mines and the remediation of tips concern the operation of available controls rather than the adequacy of the existing legal framework.

-

1.67 The suggestion that the tips register, discussed in chapter 3, should list tips associated with operational mines and categorise them as “active” could be a positive way to promote coordination between the two regimes. We leave this possibility to the Welsh Government to consider.

-

1.68 It is not open to the Senedd to repeal the 1969 Act, which applies in relation to England as well as Wales. But legislative competence to enact new legislation applying to coal tips in Wales will extend to amending the 1969 Act so that it does not apply to tips covered by the new Senedd legislation.

Recommendation 1.

-

1.69 We recommend that the existing regulatory regime for tips associated with operational mines should not be altered.

Recommendation 2.

-

1.70 We recommend that any new legislation should not apply to a tip to which the Quarries Regulations 1999 or the Mines Regulations 2014 apply.

14

-

2.1 This chapter will consider our provisional proposal that a supervisory authority with responsibility for the safety of all disused tips should be established. It will present and discuss responses to the consultation concerning the need for an authority, the question of whether it should be an existing or newly created body, the form a new body should take, and how its duty to ensure safety should be framed.

THE CASE FOR A SINGLE SUPERVISORY BODY FOR DISUSED TIPS

-

2.2 In our consultation paper, we described the allocation of responsibility for disused tips to local authorities under Part 2 of the Mines and Quarries (Tips) Act 1969. We explained how, at the time that the 1969 Act was passed, in the era of an active mining industry, disused tips were seen as a residual problem and responsibility for ensuring their safety (limited to issues of stability) was allocated to local authorities. We also explained that almost all coal tips in Wales are now disused. This has sharply increased the burden on local authorities at a time when increased rainfall due to climate change is increasing the risk of tips becoming unstable.12

-

2.3 The paper also discussed problems with the operation of the current safety regime for disused tips reported to us by experienced stakeholders, including local authorities with large numbers of tips in their areas. These problems included a loss within local authorities of specialist skill and experience over recent decades; this was the result of many factors, but chiefly the decline in the coal mining industry. We also heard that local authority resources were under severe strain.13 In addition, the breakdown of tip numbers and ownership types across Wales set out in the consultation paper illustrates the uneven distribution of responsibility for disused tips over local authorities. This places a disproportionate burden on some local authorities.14

-

2.4 Stakeholders had told us that these combined difficulties have constrained the ability of local authorities to act proactively rather than reactively in ensuring tip safety. Almost all stakeholders we spoke with in pre-consultation discussions thought that the distribution of responsibility across local authorities also impeded consistency and made it more difficult to maintain specialism.

-

2.5 In this context, a consistent approach to coal tip safety and the need for proactive safety measures suggested a need for a single oversight body. A single body would be able to provide a uniform approach to risk assessment and inspections, and prioritise the allocation of resources according to risk. We provisionally proposed the establishment of a supervisory authority whose duty it would be to supervise the management of disused tips in such a way as to ensure their safety. We asked for views.

Consultation Question 5: We provisionally propose that a supervisory authority with responsibility for the safety of all disused coal tips should be established. Do you agree? If not, please set out the alternative that you would favour.

-

2.6 Fifty-three respondents answered this question. Of these, 48 agreed with our

provisional proposal, amounting to 91% of the total, three (6%) disagreed and two answered “other”.

Reasons for agreeing

-

2.7 Reasons given for agreeing included the lack of local authority resources to take on the burden of the work required, and the advantages offered by a single authority in terms of greater consistency, expertise and independence. Respondents also referred to the need to remove any ambiguity as to where responsibility for tip safety falls.

-

2.8 The significance of restricted local authority resources was summarised by Keith Bush QC:

The consultation paper contains strong evidence from local authorities about the difficulties faced by individual authorities in seeking to implement the current Act. Those difficulties include the impossibility of developing expertise in the skills of tip regulation, as the responsibility is spread across so many individual bodies, the disproportionate administrative burden they have to shoulder if a case arises that requires robust legal action and the lack of resources that mean they do not have the capacity to fund and oversee substantial work in order to make safe tips where the owner is unable or unwilling to carry out the work.15

-

2.9 WLGA (Bridgend and Torfaen agreeing), together with Neath Port Talbot and Merthyr Tydfil, stressed the relevance of resources in supporting the proposal; their agreement was conditional on provision of additional funding for the new body:

Local authorities are already stretched and it would be helpful to have one central body with the required skills to support coal tip safety activity. It would result in a consistent approach across Wales and ensure there is capacity when needed, given the loss of expertise over recent years in local authorities in the face of financial pressures. With climate change and more intense downfalls of rain expected, the demands are likely to outweigh local authority resources in most cases.

-

2.10 Wrexham thought that a single body was the answer because “a single authority will provide consistency, expertise and resilience, but also because many local authorities, Wrexham included, have no officers (now or in the past) with the necessary geotechnical expertise”.

-

2.11 The need for greater consistency was emphasised by Jacobs UK Ltd (formerly Halcrow):

A single supervisory body is essential for achieving compliance [with] regulatory requirements and achieving a consistent and quality standard across Wales.

It will overcome the current split of responsibility across many organisations and it will allow identification and allocation of an appropriate ring-fenced level of funding for the supervisory body, which current arrangements lack.

-

2.12 The risk that a division of responsibility for tips between different bodies could lead to a lack of clarity was also emphasised by a number of respondents. Chris Seddon observed that, in his experience “where there is ambiguity regarding responsibility for safety this is exploited by all parties to avoid taking ownership”. He thought that a single supervisory authority would mitigate this risk. CLA Cymru warned against splitting responsibility between more than one authority, as “things may slip between the two”, and supported a “one size fits all” authority for this reason.

-

2.13 A number of responses focused on the ability of a single authority to pool expertise. Dwr Cymru/Welsh Water noted the “added benefit that specialist skills and experience are concentrated and developed rather than thinly spread across several organisations”.

-

2.14 The importance of the independence of a new authority was raised. Heledd Fychan MS, Sioned Williams MS and the Rhondda Cynon Taf Plaid Cymru Group emphasised that the new authority should be wholly independent and answerable to the Senedd. Other respondents, including ICE Wales Cymru, focused on the need for independence from tip owners, including both private and public owners. Wrexham explained the benefits of independence in the following terms:

A single supervisory authority is more likely to make evidence-based policy making procedures and enforcement with associated priorities without undue political persuasion. It would also avoid the issue of which Council regulates a tip site that traverses two local authority boundaries.

-

2.15 Network Rail mentioned that having one overriding responsible and accountable body would be beneficial from an insurance and claims perspective. In their view tip owners should be required to obtain specific insurance or be part of a compulsory insurance scheme, possibly with some type of joint funding arrangement which could be drawn upon in the event of an incident. An agreed claims process would save costs and bring clarity.

Reservations

-

2.16 Some respondents, while agreeing with the proposal, expressed reservations. Many noted that without adequate resources the new authority would be unable to fulfil its functions.

-

2.17 The Rhondda Cynon Taf Plaid Cymru Group emphasised the need for sufficient funding:

There should be an assurance to the new authority that any remedial work that needs to be done in order to maintain public safety will be funded. It would be pointless to have a new authority that is unable to perform its duties in full.

-

2.18 Wrexham drew on their experience of the contaminated land legislation introduced in 2001 by Part 2A of the Environmental Protection Act 1990 to warn of the need for levels of funding to be maintained. At the outset, contaminated land teams within local authorities were well resourced, but this level of funding was not sustained. Over the last ten years, they told us, diminished funding has resulted in many authorities losing staff, struggling with workloads and losing the capacity to undertake any proactive work in the field.

-

2.19 Caerphilly agreed with the proposed authority on the condition that its roles and responsibilities were expressed flexibly:

Flexibility needs to be maintained to allow [local] authorities to take on what they can (subject to funding) or pass out this function if they have no or very little tips, or no expertise in-house to manage the function.

-

2.20 Stephen Smith warned that, without sufficient resources, a new supervisory authority could run into the same problems that had hindered tip safety work under the 1969 Act:

Understandably, one of the major problems for [local authorities] has been the loss of the essential (technical) expertise and a consequent lack of focus from the authority on their duties. This is not wholly due to the shortcomings of the Act; more than likely being due to absence of a specific funding stream.

-

2.21 A number of respondents also warned that the establishment of a supervisory body was not of itself a complete solution to tip safety. Clear definition of the functions of the authority would be essential. We agree, and the chapters which follow will consider these functions in more detail.

Reasons for disagreeing

-

2.22 Joel James MS disagreed because in his view there was already a body in existence which could take on responsibility for coal tip safety, in the form of the Coal Authority. Sue Jordan thought that rather than going to the expense of establishing a new authority, those with current responsibilities should remove all tips and return the sites to their original profile. Cllr Julie Edwards did not oppose an authority in itself, but thought that it was too expensive an option unless greater responsibilities were placed on tip owners.

Discussion

-

2.23 Responses indicate almost unanimous support for a single supervisory authority, as well as broad agreement with the reasons we gave for our provisional proposal. Reservations were expressed with regard to funding, but the way in which the new regulatory regime will be funded is a policy matter for the Welsh Government, and falls outside our terms of reference. We note, however, that our impact assessment shows that the creation of a single oversight body offers potential efficiency savings, and that there are long-term economic benefits in taking a proactive approach to tip safety.

-

2.24 We do not think that the suggested alternative approach for a supervisory authority, aimed at removing tips rather than working to ensure their safety, is a viable option. We explained in our consultation paper that the view of the Coal Authority is that in most cases outright removal of a coal tip is not a realistic option. 16We have not been offered any reasons to take a different view.

-

2.25 We recommend accordingly that a supervisory authority with responsibility for the safety of all disused coal tips should be established.

Recommendation 3.

-

2.26 We recommend that a supervisory authority with responsibility for the safety of all disused coal tips should be established.

-

2.27 The remainder of this chapter will evaluate responses to questions concerning the form and duties of the new supervisory authority.

AN EXISTING OR NEWLY CREATED BODY?

Consultation Question 6: We seek views on whether the supervisory authority should be an existing body or a newly created body.

-

2.28 Forty-seven respondents answered this question, with 20 (43%) favouring a new body, and 18 (38%) preferring an existing body. Of those who preferred an existing body, 14 (78%) opted for the Coal Authority, 1 (6%) for Natural Resources Wales (NRW) and 1 (6%) for the Health and Safety Executive (HSE). The other two respondents suggested that the Coal Authority and NRW were equally preferable, or proposed a combination of the two. Nine respondents (19%) made observations but did not express a preference for either a new or an existing body.

-

2.29 With such evenly divided responses, it is important to look at the reasons expressed for these preferences.

An existing body

-

2.30 Reasons for preferring an existing body focused on the ability to provide expert knowledge, particularly in inspecting and maintaining tips, and existing systems. Some respondents mentioned potential cost savings. Professor Bob Lee thought that the creation of a new body would “derogate against the principle of integration”. Many of those expressing these views, including NRW and many local authorities, also expressed a preference for the Coal Authority to act as the supervisory authority. Merthyr Tydfil, for example, responded:

The most sensible and obvious existing organisation would be the Coal Authority to become the supervisory authority. They already have expert knowledge and existing systems in place which could be developed further to undertake any additional duties.

-

2.31 Dr Peter Brabham favoured the Coal Authority, but thought that its functions in relation to coal tips in Wales would need to be in a “totally separate newly created division”.

-

2.32 Some organisations favouring the Coal Authority noted that there could be difficulties with the status of the Coal Authority as a UK-wide body. Several observed that, if the Coal Authority were to take up the role, they would need an office base within Wales and would need to be accountable to the Welsh Government. The Welsh Local Government Association (WLGA) (Bridgend and Torfaen agreeing) and Neath Port Talbot recognised that the statutory status of the Coal Authority might not permit it to take on the role. WLGA suggested that, if this proved to be the case, the Welsh Government could establish a Welsh Coal Authority, with links to the existing Coal Authority, if it had sufficient devolved powers to allow it to do so.17

-

2.33 Network Rail noted that, if there were plans in the future to widen the regime beyond Wales, “it would make roll out to the wider UK simpler in the future” if the Coal Authority were tasked with the role.

-

2.34 Some suggested a role shared between NRW and the Coal Authority, in order to make best use of the Coal Authority’s expertise and NRW’s position within the Welsh infrastructure. Professor Bob Lee commented:

There may be room for joint responsibility with the Coal Authority undertaking responsibilities for compilation of registers, including risk assessment and management plans, and NRW pursuing matters of enforcement (including conclusion and supervision of maintenance agreements).

-

2.35 Professor Lee accepted that there was a potential drawback to this approach in that the imposition of an enforcement duty in respect of coal tips could create tensions with other NRW enforcement duties such as waste and water management, biodiversity and forestry. But he observed that it would be necessary to reconcile these tensions whether or not enforcement fell to NRW or to a separate body.

-

2.36 Some respondents noted the potential conflict of interest arising for both the Coal Authority and NRW as managers and owners of tips. Professor Lee observed:

Such conflicts are less than ideal but not entirely unknown in regulatory settings (for example environmental health and statutory nuisance duties in respect of public sector housing or planning call-in powers by the Secretary of State where there is a clear central government interest in a site).

-

2.37 One respondent, Keith Bush QC, suggested NRW as the most appropriate body, and others proposed it as a suitable alternative to the Coal Authority. The main reason given in support of this view was NRW’s existing role as the enforcement authority for reservoirs under the Reservoirs Act 1975.18 Merthyr Tydfil was supportive of NRW as an alternative body, but noted that the role would be more challenging for NRW as they did not have existing systems or experienced staff in place.

-

2.38 The British Geological Survey considered the HSE to be appropriate for the role:

HSE in Wales have a regulatory role, with a history of involvement in mines, understand risk and working in collaboration with partners - clearly in this case the Coal Authority and local authorities, as well as the British Geological Survey in a supporting role.

-

2.39 In contrast, ICE Wales Cymru thought the HSE would not be suitable, since the scope of responsibilities of the supervisory authority would extend beyond their remit, for example in environmental matters.

A new body

-

2.40 A slightly larger group of respondents favoured a new rather than an existing body. Many responses emphasised the benefits of impartiality and transparency that a new body could offer. Professor David Petley thought that “existing bodies would lack the advantages of a clean sheet organisation that is free from the complex history of tip regulation and management”. Howard Siddle supported a new body independent of all tips owners, thus excluding the Coal Authority, NRW and local authorities. In his view, no existing authority would have the knowledge, experience or resources to take on the role. ICE Wales Cymru favoured this option as a means of ensuring that the supervisory authority was free of any conflict of interest. Stephen Smith also commented on the importance of avoiding an authority acting as both “poacher and gamekeeper”.

-

2.41 Jacobs favoured a new body, but emphasised the need to ensure that lessons are learned from the knowledge and experience of the Coal Authority.

-

2.42 Monmouthshire favoured the Coal Authority, but thought that if it could not take on the role, a new body would be preferable, as “existing bodies such as local authorities and NRW are highly unlikely to have resources and the required expertise to act as a supervisory authority, either individually or collectively”. Wrexham took the same position, noting that NRW have expertise in water pollution and possibly drainage, but not in slope stability or mining.

-

2.43 Another theme in responses was the need to ensure that the authority’s attention was not diluted by multiple responsibilities. Steve Harford commented: “To add these responsibilities to an existing body would reduce its effectiveness and could result in the focus on tips being reduced”.

-

2.44 It was recognised in responses that the integration of a new authority with authorities working in related fields such as environmental protection would be important. This is in line with the requirement under the Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015 to consider how a public body’s objectives may impact on the objectives of other public bodies. Some of those favouring a new body stressed that this should not rule out using the expertise of those previously involved in other organisations. Kim Moreton pointed out the importance of building cross-disciplinary relationships, for example with local authorities, environmental stakeholders and Network Rail. Stephen Smith suggested that the Coal Authority could provide guidance on standards to employ, and NRW have expertise in public and environmental safety.

Other criteria

-

2.45 A smaller group of respondents were of the view that it did not matter whether a new or existing body took on the role, as long as the body could satisfy certain other criteria. These were identified as an appropriate structure, requisite skills and experience, independence, clearly defined responsibilities and adequate resources. As CLA Cymru put it “the authority needs to have all the tools to do its job under one roof”.

-

2.46 We discuss the responses above together with responses to the next consultation question. This asked, if a new body is established, what form it should take.

What form should a new body take?

Consultation Question 7: If a new body is established, what form should the new body take? Should it be, for example, a central public body, a corporate joint committee of local authorities under the Local Government and Elections (Wales) Act 2021, or something else?19

-

2.47 Of the 45 respondents who answered this question, 26 (57%) favoured a central public body, and 2 (4%) preferred a corporate joint committee. The remaining responses suggested other formulations or criteria which did not correspond exactly to these two categories, but in some cases contained elements of one or the other.

Reasons to favour a central body

-

2.48 A central public body was viewed by many respondents as offering streamlined processes and consistency across the whole of Wales. CLA Cymru thought that this would promote efficiency by avoiding multiple layers of bureaucracy. A central body was also considered to be better able to collaborate with other public bodies such as NRW and to call on the expertise offered by these bodies. Wrexham, for example, thought that a single public body would support a more effective partnership with other national regulators and reduce inconsistencies in enforcement.

-

2.49 Some respondents put forward options for a central body. Stephen Smith thought that a unit within Welsh Government could work well. Benefits would include direct accountability to Ministers:

This could be similar to the former land reclamation units of Welsh Office and Welsh Development Agency, who had a critical technical and management role on the delivery of land reclamation in Wales, including budget requirements.

-

2.50 As an alternative, he suggested an “arm’s length” approach delivered through a body managed by a board “comprising representatives from existing regulatory bodies enhanced by external technical / management expertise (for example from business or universities)”. This was also the model favoured by Steve Harford, who thought that an arm’s length relationship to the Welsh Government would provide the organisation with operating flexibility. An independent board of directors appointed by the Welsh

Government could provide advice and guidance to the management team of the organisation.

-

2.51 Steve Harford also considered the option of establishing a commissioner, but observed that, as a corporation sole, the organisation would not have the support of a board of directors.

-

2.52 Reasons for preferring a central public body included reasons why a corporate joint committee was not considered to be suitable. ICE Wales Cymru thought that any regional approach would be less effective:

Corporate joint committees will be regional and as such, if their geographical responsibilities are considered, more than one supervisory authority would be required and this is not recommended. As corporate joint committees are a new statutory mechanism for regional collaboration by local government, this would also raise the issue of conflict of interest with a local authority tip owner. Effective lines of communication between the supervisory authority, government, corporate joint committees, local authorities and other interested parties should be developed and maintained.

-

2.53 WLGA (Bridgend and Torfaen agreeing) and Neath Port Talbot were also concerned about a regional approach, fearing the development of regional variations and a continuation of the disproportionate burden on local authorities with large numbers of tips in their areas. They saw local government representation on the board of the new supervisory body as the way to ensure a good relationship between the supervisory authority and local authorities.

-

2.54 Keith Bush QC thought that only a central public body could resolve the difficulties faced by local authorities in carrying out their current tip safety role. Although transferring the burden to regional corporate committees would “alleviate the difficulty, it would not resolve it”.

Reasons to favour a corporate joint committee

-

2.55 Huw Williams provided the strongest statement in support of a corporate joint committee, seeing the concentration of disused coal tips in a small number of authorities as a reason for adopting the structure. He envisaged that:

-

(1) the authorities with significant numbers of tips should form a corporate joint committee;

-

(2) the remaining local authorities in Wales should enter into agency agreements with the Joint Committee to enable them to utilise the expertise of the Committee's staff (which I envisage becoming a Centre of Excellence) in compiling registers for their areas and dealing with such tip safety issues as arise in their areas; and

-

(3) powers for the Welsh Ministers to establish a statutory scheme to underpin this arrangement may be necessary to ensure that every local authority joins these arrangements.

Other proposals

-

2.56 Other suggestions including adopting a three-region approach for south, mid and north Wales (Owen Jordan). Some of these ideas were compatible with the concept of a central public body. Richard Arnold suggested a central body operating with a presence in the regions, for example by utilising local office space, workshops and plant. The Mineral Products Association thought that the authority should be a UKwide body, and that local government involvement should be avoided as this would run the risk of politicising the regime. Dr Peter Brabham suggested a body with a wide and inclusive membership: “Coal Authority, local authorities, British Geological Survey, chartered engineers, chartered geologists and other experts in tip management and possibly mine historians”.

Discussion

-

2.57 Respondents were fairly evenly divided between a newly created or an existing body, with a slight majority in favour of an entirely new body. Good reasons were given for both views, but, on balance, we think that the arguments in favour of a new body are stronger.

-

2.58 If an existing body is used, the strongest contender would be the Coal Authority. But we do not think that the proposed duties of the supervisory authority would fit well with the Authority’s statutory structure. The Coal Authority is a statutory corporation created by the Coal Industry Act 1994. Its functions do not currently involve tip safety.20 It is under the control of a UK Government department, the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, and subject to a wide power of direction on the part of the Secretary of State as well as a power of the Secretary of State to determine its financial duties. It must produce an annual report to the Secretary of State. 21If the Coal Authority were to take on the role of the supervisory authority, new functions would need to be grafted on to the legislation to provide a new function in respect of Welsh coal tip safety. The legislation would also need to provide for answerability to the Welsh Ministers, which would not fit well within the existing statutory framework.

-

2.59 In addition, there are issues of Senedd competence. The Coal Authority is a “reserved authority” under schedule 7B to the Government of Wales Act 2006. Paragraph 8 of the schedule provides that the consent of the appropriate UK Government Minister is required for a Senedd provision to:

-

(1) confer or impose a function on a reserved authority;

-

(2) modify the constitution of a reserved authority; or

-

(3) confer, modify or remove a function specifically exercisable in relation to a reserved authority.22

-

2.60 Sub-paragraph 8(5) specifies that the “appropriate minister” to provide consent is the Secretary of State. This is likely in practice to be the Secretary of State for Wales.23 The Welsh Government could seek the consent of the UK Government to a modification of the functions of the Coal Authority. We cannot see the benefit of seeking such an arrangement over the establishment of a self-standing authority in Wales, save in accessing specialist skills and, possibly, saving costs. If access to skills were required, a simpler approach would be for the new authority to contract with the Coal Authority to provide services to it. We are also doubtful as to the likelihood of cost savings, as the Coal Authority would need to form a separate division to undertake the work.

-

2.61 Another proposed existing body is the HSE. This is similarly a reserved authority, and so the same problems would arise under schedule 7B. We also agree that the HSE’s existing range of functions is not sufficiently wide to encompass a tip safety role as these are primarily concerned with workplace safety.

-

2.62 We have considered concerns about a possible conflict of interest if a tip-owning public authority were to be given the role of the supervisory authority (the Coal Authority and NRW are both tip owners/managers). 24We do not see a dual role as a problem in itself. Under the existing regime, local authorities have managed their own tips as well as tips in other ownership. If, as some respondents have suggested, the new supervisory role were to be given to a new division of NRW, the authority would be in much the same position with regard to its tips as local authorities are now.

-

2.63 The current functions of NRW are, however, somewhat different from the role a supervisory authority would need to play in securing coal tip safety. Its existing functions are primarily to manage natural resources and to protect the environment -although there is a degree of overlap with regulatory functions, for example in relation to reservoirs. It would be possible for the role of the supervisory authority to be performed by a newly-created division of NRW; we leave it to the Welsh Government to decide if this is a feasible option. If this is the approach adopted, it will be essential to give the division a clear identity as the Tip Safety Authority rather than as, for example, the “tip safety branch” of NRW. One possible model could be for the new division of NRW to act as the enforcement authority but to outsource tip safety management to the Coal Authority.

-

2.64 We think it essential that, whatever body takes on the role, it operates as a distinct statutory entity. In our view, it would be more straightforward to achieve this through the creation of an entirely new self-standing body. For these reasons, we favour the creation of a new body.

Recommendation 4.

-

2.65 We recommend that the supervisory authority should be a new body.

-

2.66 If a new body is established as the supervisory authority, responses show majority support for a central public body, although a strong minority favoured a regional approach involving one or more corporate joint committees under the Local Government and Elections (Wales) Act 2021. Overall, we are persuaded that a central public body offers the most streamlined and consistent approach.

-

2.67 There are two ways that a corporate joint committee could be established under Part 5 of the Local Government and Elections (Wales) Act 2021. Under section 70, two or more authorities may apply to the Welsh Ministers to make Regulations creating a corporate joint committee to perform either an existing function of theirs or a new “economic well-being function” created by the Act. The Welsh Ministers can create a corporate joint committee under section 74 of the Act without receipt of such a request, but only in relation to a narrower range of local authority functions: the preparation of a strategic development plan or the economic well-being function.

-