Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

The Law Commission

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> The Law Commission >> Technical Issues in Charity Law (Report) [2017] EWLC 375 (13 September 2017)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/ew/other/EWLC/2017/lc375.html

Cite as: [2017] EWLC 375

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

|

(Law Com No 375) |

|

Technical Issues in Charity Law |

|

Presented to Parliament pursuant to section 3(2) of the Law Commissions Act 1965 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 13 September 2017 |

|

HC 304 |

|

|

|

© Crown copyright 2017 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: psi@nationalarchives.gsi.gov.uk. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/government/publications ISBN 978-1-5286-0029-3 CCS0917968854 09/17 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum Printed in

the UK by the APS Group on behalf of the Controller of |

The Law Commission

The Law Commission was set up by the Law Commissions Act 1965 for the purpose of promoting the reform of the law.

The Law Commissioners are:

The Right Honourable Lord Justice Bean, Chairman

Professor Nick Hopkins

Stephen Lewis

Professor David Ormerod QC

Nicholas Paines QC

The Chief Executive of the Law Commission is Phil Golding.

The Law Commission is located at 1st Floor, Tower, 52 Queen Anne's Gate, London SW1H 9AG.

The terms of this report were agreed on 26 July 2017.

The text of this report is available on the Law Commission's website at http://www.lawcom.gov.uk.

Glossary of terms used in this report 1

The size of the charity sector 4

Trustees, staff and volunteers 5

Public donations to charities 5

Social investment by charities 7

Technical issues in charity law 7

Our recommendations for reform 11

The structure of this report 11

The team working on the project 13

Chapter 2: The different types of charity 14

The different legal forms of charities 14

The statutory definition of a charity 14

Different categories of charity under the Charities Act 2011 16

Other unregistered charities 17

Chapter 3: Financial thresholds 19

Arbitrary results from thresholds 19

Adjusting the thresholds to reflect inflation 20

Chapter 4: Changing purposes and amending governing documents 23

Figure 1: examples of circumstances in which a charity may need to amend its governing document 23

Charitable companies and CIOs 24

Differences between companies and CIOs 26

Definition of regulated alterations 27

Schemes in respect of charitable companies and CIOs 29

Figure 2: amendments that can be made under section 280 32

Figure 3: the section 62 cy-près occasions – gateways to a cy-près scheme 33

Figure 4: the section 67 similarity considerations 35

Discussion and options for reform 40

The Supplementary Consultation Paper 40

A new amendment power for unincorporated charities 42

Figure 5: majorities for trustees’ and members’ resolutions in charity law 53

The continued role of section 275 54

The Charity Commission’s discretion to consent to a change of purposes 58

Continuing role of schemes and the law of cy-près 63

Figure 6: statutory charities – the section 73 procedure 69

Figure 7: Royal Charter charities – the express power procedure 72

Figure 8: Royal Charter charities – the supplemental Charter procedure 73

Criticisms of the current law 76

(1) Unnecessary complexity, delay and costs 76

(3) Lack of transparency in the amendment process 79

Discussion and recommendations for reform 81

Royal Charter charities: improving the supplemental Charter procedure 81

Statutory and Royal Charter charities: power to make minor amendments and guidance 88

Other improvements to the amendment process 98

Higher education institutions 101

Constitutional change: the current law 101

Re-allocation of provisions 102

English HEIs: BIS 2015 Green Paper 104

Our conclusions following consultation 105

English HEIs: the Higher Education and Research Act 2017 106

HEIs with individual Acts of Parliament 108

Chapter 6: Cy-près schemes and the

proceeds of fundraising

appeals 109

General charitable intention 109

Figure 9: requirements for advertisements in the 2008 Regulations 112

Figure 10: form of disclaimer under the 2008 Regulations 113

Figure 11: notification to be given to donors who have made a Declaration 114

National Health Service charities 115

Avoiding the difficulties of failed appeals and surplus funds 115

Issue (A): failed appeals – the requirement for a general charitable intention 117

Issue (B): failed appeals – the procedures in Cases (1) to (5) 122

Issue (C): failed appeals and surplus funds – Charity Commission involvement 126

Chapter 7: Acquisitions, disposals and mortgages of charity land 129

Structure and summary of this chapter 129

The current regime: limitations on disposals and mortgages 132

Transactions to which the regime applies 132

The default rule: no transaction without the consent of the court or the Charity Commission 133

(A) Dispositions other than mortgages 134

Figure 12: the Charities (Qualified Surveyors’ Reports) Regulations 1992 136

Formalities and land registration 140

Evaluation of the current law 143

Criticisms of the Part 7 regime 143

Support for the Part 7 regime 148

Our Proposals for reform of the advice requirement 149

Restrictions on the register 151

What should the advice requirements be? 152

Options for reform of the advice requirements 155

Mortgages and leases of up to seven years 165

Recommendations for reform of the advice requirements 172

Clarifying the definition of “charity land” 173

Should the provisions concerning connected persons be retained? 175

The definition of connected persons 177

Obligations on the charity trustees 182

Existing Exceptions to the advice requirements in Part 7 188

Sales by liquidators, administrators, receivers and mortgagees 190

Disposals to other charities 191

The Universities and College Estates Acts 193

Historical background to the Universities and College Estates Acts 1925 and 1964 193

Application of Part 7 of the Charities Act 2011 195

Chapter 8: Permanent endowment 198

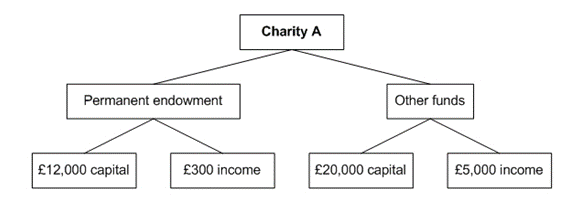

Figure 13: terminology in this chapter 200

What is permanent endowment? 201

Figure 14: examples of permanent endowment 202

The nature of permanent endowment 202

Effect on the current law and on our recommendations 206

Reformulating the definition of permanent endowment 207

Spending permanent endowment 209

Figure 15: why might charities want to spend their permanent endowment? 210

The Consultation Paper and our earlier work on social investment 214

Releasing the restrictions on spending permanent endowment 216

Sections 281 and 282 of the Charities Act 2011 216

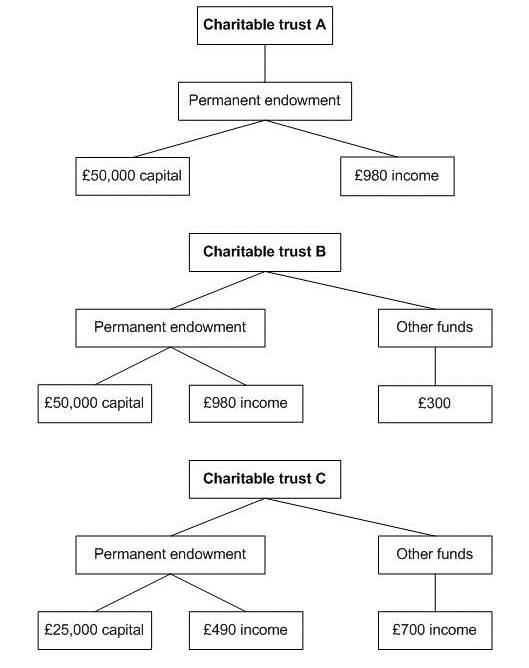

Figure 16: problems with the income and capital thresholds 218

Figure 17: problems with the income and capital thresholds 219

Sections 288 and 289 of the Charities Act 2011 224

Releasing the restrictions on permanent endowment: recommendations for reform 225

A new form of permanent endowment 226

Problems with the current law 226

Social investments with an expected negative financial return 230

Recommendations for reform 233

(1) A power to borrow from permanent endowment 233

(2) A power to engage in portfolio offsetting 236

Distinction between the two recommended powers 238

Chapter 9: Remuneration for the

supply of goods and the power

to award equitable allowances 240

Remuneration for the supply of goods 242

When is an equitable allowance awarded? 244

A power for the Charity Commission to award equitable allowances 245

The criteria to be used for awarding equitable allowances 247

Challenging decisions to award, or not to award, an equitable allowance 249

Chapter 10: Ex gratia payments out of charity funds 252

Figure 19: situations in which trustees might wish to make ex gratia payments 252

A power to make small ex gratia payments 253

The threshold for making ex gratia payments without Charity Commission consent 255

Reporting of ex gratia payments 259

The ability to exclude the power to make small ex gratia payments 259

Delegation of the decision to make ex gratia payments 260

The test for making an ex gratia payment 260

Should it be possible to delegate the decision to make ex gratia payments? 260

Potential limitations on delegation 262

Further reform suggested at consultation 266

Parallel reform of section 105 of the Charities Act 2011 266

Appeal from a decision made under section 106 of the Charities Act 2011 266

Chapter 11: Incorporations, mergers and trust corporation status 268

Structure and summary of this chapter 268

Mechanisms to effect a merger 274

Permanent endowment and special trust property 277

Recommendations for reform 278

Mechanisms to merge: section 310 vesting declarations 279

Avoiding ongoing costs following merger 286

The problem with shell charities 286

Bequests to a charity that has merged 286

Other reasons for retaining shell charities 290

Criticisms of the current law 293

Wider issues with trust corporation status 293

Which corporate bodies should obtain trust corporation status? 295

How should charitable corporations obtain trust corporation status? 296

For what purposes should trust corporation status be conferred? 297

Regulation 61 of the CIO (General) Regulations 2012 298

Chapter 12: Charity and trustee insolvency 299

Figure 20: terminology in this chapter 300

Bankruptcy and liquidation on insolvency 301

Availability of trust property to creditors 303

Insolvency of a trustee of a charitable trust 303

Uncertainties and misunderstandings 305

Permanent endowment, special trusts and restricted funds 305

Individual and corporate trustees 306

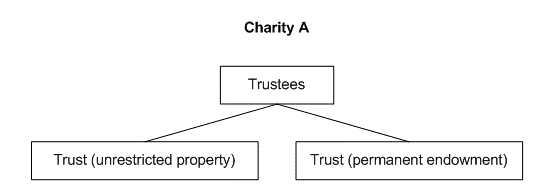

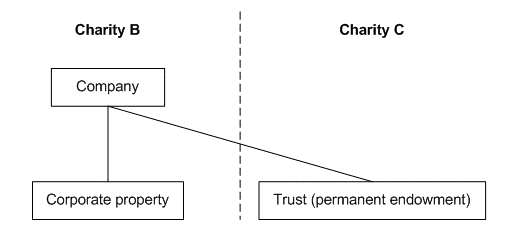

Figure 21: permanent endowment as a distinct charity 307

Charity Commission guidance 308

Further points raised by consultees 311

Applying the law to the facts of individual cases 311

Requiring a charity to change its name 314

Section 42 of the Charities Act 2011 314

Figure 22: section 42 grounds 315

Delaying or refusing registration when section 42 issues arise 317

When will the Charity Commission issue a section 42 direction? 317

Recommendations for reform 319

The scope of section 42 directions 319

Power to refuse or delay registration 323

Chapter 14: The identity of a charity’s trustees 327

Determining the identity of a charity’s members 327

Determining the identity of a charity’s trustees 328

Existing ways to deal with uncertainties about the identity of trustees 328

Circumstances in which a new power would be used 329

Chapter 15: The Charity Tribunal and the courts 334

The work of the Charity Tribunal 335

Figure 23: cases heard by the Charity Tribunal 335

A permission filter for court and tribunal proceedings 336

Figure 24: the definition of “charity proceedings” 336

Expenditure on proceedings before the courts and the tribunal 341

Charity Tribunal proceedings 342

References to the Charity Tribunal 350

Procedure for references by the Charity Commission to the Charity Tribunal 350

The powers exercisable by the Charity Tribunal when considering references 353

Chapter 16: Recommendations 355

Appendix 1: Selected Issues in Charity Law - Terms of Reference 371

Appendix 2: List of consultees 374

Appendix 3: Draft Charities Bill 379

Appendix 4: Explanatory Notes on the draft Charities Bill 422

Overview of the draft Bill 422

Territorial extent and application 424

Commentary on provisions of the Bill 424

Appendix 5: Draft regulations relating to Chapter 7 456

Appendix 6: Draft regulations relating to Chapter 8 461

Appendix 7: Means of challenging Charity Commission decisions 462

Appendix 8: Worked examples of

distribution of assets

on insolvency 463

Glossary of terms used in this report

|

Appropriation |

Appropriation is “the process whereby [the person responsible for administering the estate] uses a specific asset to meet in full or in part the pecuniary entitlement of a beneficiary”.[1] When land is appropriated to a beneficiary, the beneficiary acquires the beneficial interest in the property. |

|

Assent |

An assent is the transfer of ownership of an asset to a person entitled to that asset pursuant to the administration of a deceased’s estate. It is “an acknowledgement by a personal representative that an asset is no longer required for the payment of the debts, funeral expenses or general pecuniary legacies”.[2] |

|

Beddoe orders |

In court proceedings, charity trustees can seek a Beddoe order which provides them with advance assurance that the proceedings are in the interests of the charity and that the costs incurred by the trustees can properly be paid from the charity’s funds. |

|

CAAV |

Central Association of Agricultural Valuers |

|

CLA |

Charity Law Association |

|

Charity |

An institution falling within section 1 of the Charities Act 2011; see para 2.3. |

|

Charity Commission Guidance |

Guidance published by the Charity Commission and available on its website. The guidance comes in two series: the “CC” series which is intended for external use, and Operation Guidance (the “OG” series) which is intended for internal use but which provides further detail on the Commission’s approach to many issues. |

|

Charity trustees |

Defined in section 177 of the Charities Act 2011 as “those responsible for the control and management of the charity”. It includes the directors of a charitable company and the management committee of an unincorporated association. |

|

CIO |

Charitable incorporated organisation: a form of corporate charity that was introduced by the Charities Act 2006 as an alternative to the limited company. It provides the benefits of incorporation without requiring dual registration with both the Charity Commission and with Companies House. |

|

Consultation Paper |

The Law Commission’s principal consultation paper on Technical Issues in Charity Law.[3] |

|

Cy-près |

Cy-près means “as near as possible”. When a charitable purpose cannot be carried out, the Charity Commission can direct under a scheme that the funds should be used for other similar charitable purposes. |

|

Designated land |

Land held on trusts stipulating that it must be used for the purposes of the charity: Charities Act 2011, section 275(1). |

|

Diocesan glebe land |

Land vested under the Endowments and Glebe Measure 1976 in the diocesan board of finance of the Church of England. It is used for investment purposes to generate income for the Diocesan Stipend Fund: Endowments and Glebe Measure 1976, section 15. |

|

Disponee |

A person to whom an interest or estate in land is granted or conveyed. For example, a buyer of a freehold or leasehold estate, a tenant under a lease, a chargee, or a person who is granted an easement. |

|

Expendable endowment |

Property which is subject to a restriction on being spent, unless and until the trustees decide to spend it; the trustees have a discretion to spend the capital. |

|

Functional permanent endowment |

Permanent endowment that generally does not produce an income but is used by the charity to pursue its purposes, for example a village hall or a recreational ground. The charity might be able to sell the property and purchase other property that performs the same function, but it cannot spend the proceeds of any sale on its day-to-day activities. |

|

Governing document |

The document setting out a charity’s purposes, the powers and duties of those responsible for its management and administration, and the procedures to be followed in exercising those powers. “Governing document” is used as a generic term, regardless of a charity’s legal form. The Charities Act 2011 uses the term “trusts” to refer to a charity’s governing document, regardless of whether or not it is in fact a trust. |

|

Investment permanent endowment |

A fund of assets, such as shares, that produce an income to fund the charity’s activities. The charity can sell an investment in the fund to purchase another, but it cannot sell an investment and spend the proceeds to further its purposes. |

|

NAEA |

National Association of Estate Agents |

|

Permanent endowment |

Property that is held by, or on behalf of, a charity subject to a restriction on being spent: section 353(3) of the Charities Act 2011. |

|

Residuary gift |

The “residue” of an estate is all that is left after the payment of (i) the deceased’s debts, (ii) the expenses of the administration of the estate, and (iii) the payment of legacies. When a testator leaves the residue of the estate to a named person, it is a “residuary gift”. |

|

RICS |

Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors |

|

Royal Charter charities |

A charity that is incorporated or regulated by a Royal Charter. |

|

Specific devise |

A gift by will of particular land to a named beneficiary. |

|

Statutory charities |

A charity that is incorporated or regulated by an Act of Parliament. |

|

Supplementary Consultation Paper |

The Law Commission’s supplementary consultation paper on Technical Issues in Charity Law.[4] |

Technical Issues in Charity Law

To the Right Honourable David Lidington MP, Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice

Chapter 1: Introduction

Introduction

1.1 This report analyses various issues in charity law and makes recommendations that the law should be reformed.

1.2 Charities occupy a special place in society and in law. They exist for the benefit of the public.[5] Each has a purpose, ranging from the relief of poverty to the promotion of the arts to the advancement of environmental protection.[6] Charities come in all shapes and sizes, and their aims range from focusing on local issues to a nationwide or global sphere of interest.

1.3 It is a fundamental principle that, for an institution to be a charity, its purposes must be exclusively charitable.[7] A charity must exist for the benefit of the public generally, not for the benefit of private individuals or entities.

1.4 The Charity Commission for England and Wales registers and regulates charities, though many charities are not required to be registered. Of those unregistered charities, some are nevertheless regulated by the Charity Commission; others are not. We explain these different categories of charity in Chapter 2.

The size of the charity sector

1.5 There are approximately 167,000 charities in England and Wales registered with the Charity Commission,[8] with a combined annual income of over £74 billion.[9] In 2012, it was estimated that there were a further 191,000 unregistered charities with a combined income of £57.7 billion.[10] Charities hold significant assets; registered charities alone have total assets worth over £259 billion.[11]

Trustees, staff and volunteers

1.6 Charities depend on people. Charities are overseen and controlled by their trustees, who are generally unpaid. Trustees range significantly from local residents who are passionate about a local cause through to professionals whose skills and experience can assist in the oversight of a large charity’s operations. Small charities often rely solely on the trustees and other volunteers to carry out their activities; others have sufficient resources to employ (sometimes numerous) staff. Charity law therefore applies to and affects a wide range of people, many of whom will not have access to legal advice on its application.

1.7 There are more than 951,000 trustees of registered charities, and registered charities employ over 1.5 million people and are supported by over 3.5 million volunteers.[12] These figures would increase significantly if the trustees, staff and volunteers of unregistered charities were included (but about whom there are no data).

1.8 The importance of charities is reflected by the significant donations made to them each year; charitable giving by individuals in the United Kingdom in 2016 was estimated to be £9.7 billion.[13] According to a 2016 survey conducted by the Cabinet Office, in an average four-week period, around three-quarters of the 3,000 people interviewed gave to a charity, donating an average of £22.[14]

1.9 The Charity Commission’s first statutory objective is to increase public trust and confidence in charities.[15] Research published by the Charity Commission in 2016 showed that public trust and confidence in charities had reached its lowest level since 2005.[16] This fall is thought to have been a result of negative media coverage about charities in 2015/16 and a distrust as to how donations were being spent, in particular the proportion of donations which were reaching the end cause.[17] However, research published by nfpSynergy later in 2016 indicated that public trust in charities is returning, rising from 48% in autumn 2015 to 60% in autumn 2016.[18] The most recent research published by the Charity Commission explains that the level of public trust in the charity sector is comparable with that in schooling and childcare and the food and drink industry, and significantly higher than that in other industries such as financial services and affordable housing.[19]

1.10 During the course of our project, there has been significant media coverage relating to charities, principally concerning fundraising practices and the collapse of Kids Company. Fundraising was an issue addressed by a cross-party review in 2015,[20] measures were included in the Charities (Protection and Social Investment) Act 2016,[21] and the new Fundraising Regulator is already operational.[22] Fundraising does not form part of our terms of reference.

1.11 The charity Kids Company closed in August 2015 amid allegations of financial mismanagement and governance problems.[23] The Charity Commission opened a statutory inquiry into the charity soon after, in line with its duty to promote public trust and confidence in charities. Various other inquiries have been conducted into the collapse of the charity, including by the Public Accounts Committee and the Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee.[24] These inquiries have focussed on issues surrounding public money granted to the charity without sufficient competitive tendering and assessment of the way in which the charity was run. The Insolvency Service has recently stated its intention to bring proceedings against the former directors of the charity which could disqualify them from acting as company directors.[25] While the concerns raised by the inquiries to date are relevant to the need, in our recommendations, to balance deregulation against proper protection of charity assets, none of them relate directly to the terms of reference for this project. We therefore do not directly address these issues in this report.

Background to the project

1.12 Our project on selected issues in charity law originated from our Eleventh Programme of Law Reform.[26] The Charity Commission had suggested a review of certain issues affecting charities established by statute and by Royal Charter. We were also mindful of the statutory review[27] of the Charities Act 2006 that was about to be conducted by Lord Hodgson of Astley Abbotts, which we thought might raise further legal issues that were ripe for reform. Lord Hodgson’s report, published in 2012, made over 100 recommendations.[28] Amongst those recommendations, he highlighted various technical legal problems faced by charities and suggested that they be given further consideration by the Law Commission. We agreed to include many of those issues within our project, which started in 2013. Our terms of reference are set out in Appendix 1.

1.13 We divided the project into two parts. The first part concerned social investment by charities; the second the remaining issues in our terms of reference.

Social investment by charities

1.14 We published a Consultation Paper on social investment by charities in April 2014[29] and a paper setting out our recommendations in September 2014 (“the Social Investment Report”).[30] We then drafted a Bill to give effect to our principal recommendations (a) for the creation of a statutory power for charities to make social investments, and (b) to set out the duties that should apply when charity trustees make social investments. Our draft Bill has since been implemented as part of the Charities (Protection and Social Investment) Act 2016, subject to one modification.[31]

Technical issues in charity law

1.15 This report concludes the second part of our project covering all the remaining issues in our terms of reference. We also added one issue that arose from our work on social investment, namely a review of the law relating to the use of permanent endowment.

1.16 Our project is not a full review of charity law. Our terms of reference relate to selected technical issues. Those issues do not include controversial matters, such as the law of public benefit and the charitable status of independent schools. Lord Hodgson made recommendations in respect of some of the issues within our terms of reference; others he simply highlighted as creating difficulties and worthy of more detailed consideration by the Law Commission. In formulating our recommendations for reform, we have carefully considered Lord Hodgson’s comments and (when he made them) his recommendations. Our review has not, however, been limited to an assessment of his recommendations. Rather, we have looked afresh at the various issues in our terms of reference including their wider context.

The aims of reform

1.17 Our project concerns various technical legal issues in charity law. Whilst technical, they are important and have very practical consequences for charities. Lord Hodgson has likened regulatory burdens on charities to the barnacles that slow down a ship.[32] Uncertainties in the law and unnecessary regulation can delay or prevent charities’ activities, discourage people from volunteering to become trustees, and force charities to obtain expensive legal advice. And whilst some (particularly large) charities have ready access to legal advice, it is beyond the reach of others.

1.18 Charities have an important role and the law should both protect and properly regulate them. Our project is intended to further these objectives by removing unnecessary or inefficient regulation while safeguarding the public interest in ensuring that charities are properly run.[33] Charities must be carefully regulated, but not every regulatory requirement is indispensable. For example, in Chapter 7 we recommend relaxing, but not removing, the regulation of land transactions by charities; rather than requiring charities to obtain advice from members of the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (“RICS”), we recommend that charities should also be able to satisfy the regulatory requirements by obtaining advice from certain other property professionals.

1.19 Our recommendations aim to support and equip the charity sector by ensuring that the legal framework in which it operates is fair, modern, simple and cost effective. More specifically the recommendations aim to fulfil the following objectives.

(1) To remove unnecessary regulation and bureaucracy in order to maximise the efficient use of charitable funds. The aim is to prevent the disproportionate diversion of charitable assets and trustee time on compliance with regulation from which little or no benefit is derived.

(2) To increase the flexibility of trustees to make decisions in the best interests of their charities, in particular to give trustees wider or additional powers to make decisions without having to obtain authorisation where appropriate.

(3) To confer wider or additional powers on the Charity Commission in order to increase its effectiveness. This includes enabling the Commission to carry out its current functions more efficiently and to take action where it ought to be able to but cannot currently (for example to regulate or assist charities).

(4) To ensure adequate protection of charity property in order to enhance donor confidence and public trust, in particular supporting confidence in the use of donations currently and in the future.

(5) To remove inconsistencies and complexities in the law making it clearer for charity trustees, staff, volunteers and professional advisers seeking to apply it and comply with it as well as reducing legal and other professional costs. This includes seeking to reduce the potential for unintentional mistakes and the associated costs of addressing them.

1.20 There is a link between good regulation and public trust and confidence in charities. Speaking at the Charity Commission’s Annual Public Meeting in 2017, the Chair of the Charity Commission, William Shawcross, said that the Commission wished to add to its focus on compliance “a renewed emphasis on enablement.” He argued that “enabling trustees to run their charities better is key to public confidence in charity and to the effective use of charitable resources.”

Consultation

1.21 In March 2015 we published our consultation paper, Technical Issues in Charity Law (“the Consultation Paper”)[34] which made proposals to:

(1) give charities wider or additional powers and flexibility;[35]

(2) reduce the regulation of certain transactions by charities;[36]

(3) confer wider or additional powers on the Charity Commission;[37] and

(4) rationalise the law and remove inconsistencies.[38]

1.22 Two issues arose from the consultation on which we did not expressly invite consultees’ views: first, a particular point relating to changing a charity’s purposes; and second, trust corporation status. We wanted to hear more about these issues before deciding on our final recommendations. We therefore published a supplementary consultation paper (“the Supplementary Consultation Paper”)[39] in September 2016 focussing on those two issues.

1.23 Consultees were supportive of our project and keen to engage in the detail of our proposals. There was a clear sense that the issues in our project, although technical and difficult, are nevertheless important for charities and that reform has the potential to improve the legal framework within which charities operate.

1.24 Many consultees commented on the need for a balance between various competing interests in devising recommendations for reform.

(1) Charities should be given flexibility and autonomy in how they are run.

(2) “Inefficient and unduly complex legal provisions that impose unnecessary administrative and financial burdens on charities” should be removed.[40]

(3) Proper oversight and accountability of charities is important to maintain public trust and confidence in the sector.

(4) Regulation should be proportionate; “a regulatory regime whose administrative costs swallow up a large part of the benefit is inappropriate”.[41]

(5) Deregulation can be beneficial for all charities; small charities, in particular, might benefit from reduced compliance costs. Conversely, however, “good regulation can be helpful for smaller charities, providing a proper structure within which to operate”.[42]

(6) Third party rights should be respected, but should not unduly hamper the administration of a charity or prevent change.

1.25 There is often a tension between these aims, and we agree with consultees’ general comments about the need for a balance. The difficulty is in deciding how to reach the balance between those competing aims.

1.26 During the consultation period, we attended various consultation events:

(1) a public consultation event in Bristol, hosted by Veale Wasbrough Vizards LLP;

(2) a consultation event for charity professionals, practitioners and academics, organised and hosted by the University of Liverpool Charity Law and Policy Unit, at the University’s London campus; and

(3) meetings with the Association of University Legal Practitioners, the Association of Charitable Foundations, the National Council for Voluntary Organisations, the Charities’ Property Association, the Churches’ Legislation Advisory Service, and officials from the Privy Council Office, Attorney General’s Office, Department for Business, Innovation and Skills (as it then was), and the Welsh Government.

1.27 The Consultation Paper also featured in the sector press.[43]

1.28 We had an enthusiastic response to our consultations. We received written responses to our initial consultation from 91 consultees and an additional 26 written responses to our supplementary consultation, many of which were very detailed. The consultees who responded are listed in Appendix 2. All of the main stakeholders in the charity sector were represented.[44]

1.30 We have held follow-up meetings with members of the CLA working group, the Charity Commission, the Charities’ Property Association and the institutions governed by the Universities and College Estates Act 1925 to discuss aspects of their responses and our recommendations for reform.

Our recommendations for reform

1.31 Consultation revealed general consensus on some issues and a range of views on others. Not everyone will agree with all of our recommendations for reform, but consultation has successfully elicited the different viewpoints which has been helpful to us in formulating our recommendations. On many issues, we follow our provisional proposals in the Consultation Paper, but in some areas we have departed from them following comments from our consultees. The input of consultees has been vital to the preparation of all of our final recommendations for reform.

The structure of this report

1.33 In Chapters 4 and 5, we discuss the amendment of charities’ purposes and other provisions in their governing documents. Chapter 4 concerns the most common legal forms of charities, and we make recommendations to align more closely the amendment powers of corporate and unincorporated charities. Chapter 5 concerns charities that are governed by statute or by Royal Charter and we make recommendations to improve the procedures by which they can amend their governing documents. In Chapter 6, we examine the rules governing the distribution of the proceeds of failed fundraising appeals.

1.34 In Chapter 7, we discuss the regime that applies to charities when they dispose of land. We then turn to the law governing the use of permanent endowment in Chapter 8; we recommend changes to the procedures by which charities can release the restrictions on spending their permanent endowment and recommend the creation of a new statutory power to borrow from permanent endowment as well as a new power to make certain social investments using permanent endowment.

1.35 Chapter 9 addresses two issues: the payment of trustees for the provision of goods to their charity and empowering the Charity Commission to award an equitable allowance to a trustee who has made an unauthorised profit in breach of his or her fiduciary duties to the charity. In Chapter 10 we recommend changes to the circumstances in which ex gratia payments (payments to third parties who have a moral, but not a legal, claim to the charity’s property) can be made by a charity.

1.36 In Chapter 11, we consider the regime that governs the incorporation and merger of charities, and consider a related issue concerning trust corporation status. We then look at the insolvency treatment of property held on charitable trust, including permanent endowment and special trust property (Chapter 12).

1.37 Chapters 13 and 14 concern two discrete powers of the Charity Commission: the power to require a charity to change its name and to refuse to register a charity unless it changes its name (Chapter 13); and the power to determine the identity of the charity’s trustees and members (Chapter 14). We make recommendations that these powers be expanded.

1.38 In Chapter 15, we discuss particular issues that have arisen since the Charity Tribunal was established by the Charities Act 2006 and make recommendations for reform.

1.39 Chapter 16 gathers together all of our recommendations for reform.

1.40 Appendix 1 sets out the terms of reference for our project. A list of all consultees appears at Appendix 2.

1.41 Appendix 3 contains a draft Bill that would implement our recommendations for reform, and accompanying Explanatory Notes appear at Appendix 4. Appendices 5 and 6 contains draft statutory instruments that would implement those of our recommendations that require secondary legislation. Appendix 7 summarises the means of challenging decisions of the Charity Commission, which is discussed in Chapter 9. Appendix 8 contains some worked examples about the law of insolvency that relate to Chapter 12.

1.42 Alongside this report, we are publishing:

(1) a summary of this report;

(2) a marked-up version of the Charities Act 2011, reflecting the amendments that would be made to the Act following implementation of the draft Bill at Appendix 3 to this report;

(3) an Impact Assessment; and

(4) an Analysis of Responses to the Consultation Paper and the Supplementary Consultation Paper.

1.43 Each of these documents is available on our website: www.lawcom.gov.uk.

1.44 All websites referred to in this report were last visited and correct on 24 August 2017.

Acknowledgements

1.45 Our thanks go to all those who responded to our two consultation papers (listed in Appendix 2) or who have supported our project in other ways. We are grateful for the work, time and careful thought they have given to the detailed issues covered in this report. We are also grateful to those listed in paragraph 1.26 above who have organised and hosted consultation events which enabled us to engage with a wide range of stakeholders.

1.46 Throughout our project we have been assisted by those consultees listed above who have generously given their time to meet with us and discuss some of the most difficult aspects of this area of law and offer feedback on our recommendations. Particular thanks go to our consultants, Con Alexander, Rachel Tonkin and the members of the charities team at Veale Wasbrough Vizards LLP for sharing their expert views on the issues discussed in this paper and on early drafts of this report and Bill; the CLA Working Party, and its Chair Nicola Evans (of Bircham Dyson Bell LLP), for meeting with us on various occasions, for their comments on an early draft of the Bill and for their input for our Impact Assessment; and to Judge McKenna, Principal Judge of the First-tier Tribunal (Charity) for sharing her expertise on our reforms regarding the Charity Tribunal.

1.47 Finally, we thank the officials from the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, the Charity Commission, the Attorney General’s Office, the Privy Council Office, the Ministry of Justice, the Tribunal Procedure Committee, the Welsh Government, HM Land Registry, the Department for Education and the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, who have given detailed feedback on our recommendations and valuable input for our Impact Assessment.

The team working on the project

1.48 The following members of the Property, Family and Trusts team have contributed to this report at various stages: Matthew Jolley (team manager); Daniel Robinson (team lawyer); Elizabeth Drummond (team lawyer); Kimberley Ziya (research assistant); Emma Loizou (research assistant); and James Linney (research assistant).

Chapter 2: The different types of charity

Introduction

2.1 In order to understand our recommendations for reform of charity law, it is important to be familiar with the different legal forms that charities can take as well as the categorisation of charities in the Charities Act 2011.

The different legal forms of charities

2.2 Charities take various different legal forms. Several of the technical issues raised in this report turn on the legal form of the charity, particularly whether it is incorporated (and therefore has a legal personality separate from its trustees or members) or unincorporated (and therefore has no separate legal personality).

The statutory definition of a charity

2.3 Section 1(1) of the Charities Act 2011 defines “charity” as an institution that is established for charitable purposes only, and falls to be subject to the control of the High Court in the exercise of its jurisdiction with respect to charities. This definition does not distinguish between the different legal forms of charities[45] and the Charities Act 2011 applies to all charities regardless of their legal form.[46]

Companies

2.4 Charities can be incorporated as companies. They are governed by the Companies Act 2006 and must be registered at Companies House (as well as being registered by the Charity Commission).[47] Charitable companies are usually limited by guarantee, rather than by shares. A charitable company’s governing document is its articles of association. The Charity Commission publishes model articles of association for charitable companies.[48]

Charitable incorporated organisations

2.5 The charitable incorporated organisation (“CIO”) is a new form of incorporated charity that was introduced by the Charities Act 2006 as an alternative to the limited company. It provides the benefits of incorporation without requiring dual registration with both the Charity Commission and with Companies House. The membership of a CIO may be limited to its trustees (the “foundation” model), or it may have members who are not trustees (the “association” model). A CIO’s governing document is called its constitution. The Charity Commission publishes a model constitution for CIOs.[49]

Charities incorporated by Act of Parliament

2.6 A small number of charities have been incorporated by Act of Parliament. The incorporating Act will often contain the provisions regulating the purposes and administration of the charity, but some of these provisions may be found in a later Act or Acts (or indeed in another instrument). We discuss charities incorporated by Act of Parliament, which we refer to as “statutory charities”, in Chapter 5.

Charities incorporated by Royal Charter

2.7 A charity (or the governing body of a charity) may be incorporated by a Royal Charter granted by the Sovereign.[50] Charters are granted on the advice of the Privy Council, which advises on the exercise of the Sovereign’s duties and common law powers. Like other corporate bodies, Royal Charter corporations are legal persons distinct from their individual members.[51] The governing documents of charities (or trustee bodies) incorporated by Royal Charter typically comprise the incorporating Charter (and any supplemental Charters), bye-laws and regulations. We discuss Royal Charter charities in Chapter 5.

Community benefit societies

2.8 Community benefit societies, previously known as industrial and provident societies, can be charities and are governed primarily by the Co-operative and Community Benefit Societies Act 2014.

Other incorporated charities

2.9 Charities have occasionally been incorporated by prescription, by a lost Charter being presumed, and by custom.[52]

2.10 An unincorporated charity will either be a trust or an unincorporated association.

Trusts

2.11 A charitable trust involves one or more trustees holding property on trust for charitable purposes. The charity has no members. The governing document will generally be a trust deed or declaration of trust but it may also be a Charity Commission scheme,[53] a will or other document setting out the terms of the trust.[54] The Charity Commission publishes a model trust deed for charitable trusts.[55]

Unincorporated associations

2.12 An unincorporated association has been described as “an association of persons bound together by identifiable rules and having an identifiable membership”.[56] The rules of the association contain the contractual rights and obligations enforceable by the members against one another. The rules of a charitable unincorporated association usually provide for the management of the affairs of the charity to be the responsibility of a committee elected by the members.[57] The governing document is called a constitution. The Charity Commission publishes a model constitution for unincorporated associations.[58]

Different categories of charity under the Charities Act 2011

2.13 There are four categories of charity under the Charities Act 2011, and the application of the Act to any given charity depends on the category into which it falls. The legal form of a charity (see paragraphs 2.4 to 2.12) has no bearing on its categorisation under the Act.

2.14 Every charity must register with the Charity Commission, unless it is:

(1) an exempt charity (see paragraph 2.15);

(2) an excepted charity with an annual income of £100,000 or less (see paragraph 2.16);[59] or

(3) a charity with an annual income of £5,000 or less (see paragraph 2.18).[60]

2.15 Certain charities are exempt from the requirement to register with the Charity Commission, and from other (but not all) provisions of the Charities Act 2011.[61] They are usually regulated by another body (the “principal regulator”) whose functions overlap with those of the Commission. Exempt charities are listed in Schedule 3 to the Charities Act 2011.[62] They include:

(1) most English universities;[63]

(2) other educational bodies, such as higher and further education corporations, academies, and foundation and voluntary schools;[64] and

(3) various museums and galleries, such as the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Science Museum and the British Museum.[65]

2.16 Certain charities are “excepted” from charity registration by an order of the Secretary of State or of the Charity Commission.[66] Unlike exempt charities they are still regulated by the Charity Commission in the same way as regular charities. Excepted charities include:

(1) some churches and chapels;

(2) some charities that provide premises for schools;

(3) Scout and Guide groups; and

(4) certain armed forces charities.[67]

2.17 However, even if a charity is granted “excepted” status, it is nevertheless required to register with the Charity Commission if its income is over £100,000.

2.18 Charities with an annual income of £5,000 or less are not required to register with the Charity Commission,[68] unless they are CIOs which must register with the Commission regardless of income.

Terminology

2.19 This report discusses various technical legal issues and it is sometimes unavoidable that technical legal or sector specific terms are used. We define these terms in the Glossary at pages 1 to 3 of this report but highlight three key definitions here.

2.20 References to “charities” in this report are to all institutions falling within section 1 of the Charities Act 2011, unless we expressly refer to a particular legal form of charity.

2.21 Section 177 of the Charities Act 2011 defines those responsible for the control and management of charities as “charity trustees”. We refer to them as “charity trustees” or just “trustees”. Not all of those who control and manage charities are trustees as a matter of trust law; for example, charitable companies are run by directors, not trustees. Nevertheless, the terms “charity trustee” and “trustee” are widely accepted as covering all those who run charities, including directors. We use the term “trustee” in that sense, save where we make clear that we are referring specifically to the trustees of a trust.

2.22 A charity’s governing document sets out (amongst other things) its purposes, the powers and duties of those responsible for its management and administration, and the procedures to be followed in exercising those powers. We use this as a generic term for the rulebook of all charities, whatever their legal form. The Charities Act 2011 uses the term “trusts” to refer to a charity’s governing document, regardless of whether or not it is in fact a trust.[69]

Chapter 3: Financial thresholds

Introduction

3.2 There are numerous financial thresholds in the Charities Act 2011. For example:

(1) the statutory requirement to register depends on whether the charity’s annual income exceeds £5,000 and, in the case of an excepted charity, whether its annual income exceeds £100,000;[70]

(2) registered charities must state that they are registered charities in documentation soliciting money if their annual income exceeds £10,000;[71]

(3) the reporting and accounting requirements differ depending on the charity’s annual income;[72] and

(4) the availability of various powers depends on a charity’s income or the value of its capital.[73]

3.3 There is often a power for these financial thresholds to be changed by secondary legislation, although such a power is rarely used.[74] Our project includes consideration of the income thresholds in sub-paragraph (4) above.

Arbitrary results from thresholds

3.5 We agree that financial thresholds can produce arbitrary results. Many of the statutory provisions that include financial thresholds fall outside our terms of reference.[75] Where provisions that include financial thresholds fall within our project, our recommendations would remove some of the arbitrariness that they would otherwise produce.[76] Our recommendations do, however, continue to distinguish between large and small charities so it is inevitable that some arbitrary results, as identified by the CLA, will remain. We think that it can be helpful to have different regulatory regimes for different sized charities, and financial thresholds are the best way to create a simple and clear rule to determine whether a charity or a fund is “small”; indeed, there is no obvious alternative. Moreover, income thresholds will continue to exist elsewhere in the Charities Act 2011 (where they are intended to differentiate between different sizes of charity), particularly concerning registration, accounting and reporting.

Adjusting the thresholds to reflect inflation

3.6 Lord Hodgson noted that “wherever the statutes have specific monetary amounts there is the challenge of declining ‘value’. … It would be helpful for an automatic inflation adjuster to be built in to the regulations.” The CLA made similar comments and said that financial thresholds “tend not to be reviewed and updated with any regularity, or at all” so any recommendation to increase, or introduce, any threshold will be “in effect, set in stone”.

3.7 We acknowledge these concerns about financial thresholds in legislation; they do not keep pace with inflation, and (depending on Governmental priorities and resources) they might rarely be reviewed, let alone increased. We note that the financial thresholds in the Charities Act 2006 with which our project is concerned have not been increased in the 10 years since that Act was passed.[77] We can therefore see the advantages of Lord Hodgson’s suggestion.

3.8 We make one recommendation to increase an existing financial threshold which does not, in fact, reflect changes to the value of money caused by inflation, but rather a desire to expand the scope of a power so as to include more charities.[78] But having set that new threshold, and having created others,[79] should they be increased in line with inflation?

3.9 We have considered possible mechanisms to incorporate inflation adjustment into the statutory financial thresholds within the scope of our project. For example, the Inheritance and Trustees’ Powers Act 2014 gives effect to a previous Law Commission recommendation that the statutory legacy of £250,000 for a surviving spouse on intestacy (where the deceased also had children) should be increased every 5 years in line with inflation, rounded up to the nearest £1,000.[80] The Lord Chancellor is required to make an order specifying the amount of the statutory legacy at least every 5 years.[81] It would be possible to provide that the financial thresholds in the Charities Act 2011 should similarly be increased in line with inflation at least every 5 years.

3.10 As noted above, many financial thresholds in the Charities Act 2011 fall outside our terms of reference, so we cannot recommend the incorporation of a statutory inflation adjustment mechanism into them. Some consultees emphasised that the drive should be towards consistency between the thresholds rather than divergence between them. It would be inconsistent to introduce a statutory inflation adjustment mechanism only for those financial thresholds in the Act that fall within our terms of reference.

3.11 However, even if all thresholds fell within our terms of reference, we would be cautious about automatic inflation adjustment. There are numerous financial thresholds in the Charities Act 2011 and they perform various different roles. Unlike the statutory legacy on intestacy, the financial thresholds determine the regulatory obligations of charities and the availability of various powers.

3.12 For financial thresholds that have regulatory implications (as opposed to determining the availability of enabling powers), it is important that any changes are widely publicised. There is also benefit in such a threshold being a simple, round number that does not change regularly to avoid confusion, complexity, and compliance and administration costs. We are not convinced that it would be helpful for these thresholds to change by small amounts on a regular basis. For example, we do not think that charities and their advisers would wish to see the threshold above which excepted charities must register change from £100,000 now to £105,000, and then to £108,000 a few years later, and then to £115,000, and so on. Each time thresholds change, it is necessary for charities and professional advisers to spend time becoming familiar with the changes, and for the Charity Commission and other bodies to issue revised guidance to reflect the changes.

3.13 Similarly, even if automatic inflation adjustment was limited to facilitative powers without regulatory implications, regular changes to the thresholds would still have the potential to cause confusion, complexity, and compliance and administration costs, potentially for little benefit (for example, in times of low inflation).

3.14 We do not therefore think that it would be helpful for there to be an automatic inflation adjustment mechanism built into the Act in relation to all, or particular categories of, financial thresholds. We do however think that it would be helpful for all financial thresholds in the Act to be reviewed periodically with a view to increasing them to reflect inflation. Such a review could be every five or ten years, or more frequently at times of high inflation.

3.15 We think that this approach would enable Government to make a considered decision about whether inflation adjustment is appropriate, rather than it being automatic. It would balance the desirability of keeping the thresholds up to date against the desirability of simplicity in the overall regime, ensuring consistency, and avoiding unnecessary costs caused by a transition to an amended regime. For example, charities with an income over £25,000 must send annual reports and accounts to the Charity Commission. If inflation was low and adjustment after five years would see the threshold go up to only £25,500, it might be a sensible decision to keep the threshold at £25,000 until inflation would see an increase to, say, £30,000. We think that the sector as a whole would favour this discretionary approach over an automatic inflation adjustment.

3.16 Changes to thresholds that were not intended to reflect inflation (such as the recent increase in the audit threshold from £500,000 to £1 million)[82] would still be possible as a separate (though perhaps concurrent) exercise.

Chapter 4: Changing purposes and amending governing documents

Introduction

4.1 Part 2 of the Consultation Paper, and Chapter 2 of the Supplementary Consultation Paper, examined the ways in which charities can change their purposes and amend their governing documents. With the passage of time, new needs will arise and unforeseen eventualities will occur, requiring charities to amend their governing documents to ensure their continuing effectiveness; we give some examples in Figure 1. The Charity Commission encourages charity trustees to keep their governing documents under review and consider whether they need to be amended.[83] Consultation responses revealed general agreement as to the importance of ensuring that changes can be made as quickly and efficiently as possible, whilst retaining safeguards to ensure that proposed amendments are appropriate.

|

Figure 1: examples of circumstances in which a charity may need to amend its governing document (1) To change the administrative procedures of the charity.A charity may wish to change the process by which its trustees are appointed or by which members are admitted. Or a charity may prefer to communicate with its members and arrange general meetings by email to avoid the time and expense involved with postal communications, and may need to amend a provision in its governing document – for example, requiring first class post – in order to do so. (2) To expand or limit the charity trustees’ powers.A charity’s governing document may need to be amended to permit the trustees to borrow money, to purchase or lease property, or to employ staff. Conversely, an amendment may be made to restrict the trustees’ powers, such as the default investment power under section 3 of the Trustee Act 2000. (3) To update the governing document following legislative changes.For example, a charity’s governing document may need to be amended to reflect changes in equality or employment law. (4) To remove anachronistic or offensively worded provisions.Historic governing documents may contain provisions that are now out of date or are offensive. (5) To change the charity’s name.Similarly to the provisions of a governing document, a charity’s name may use words that have become out of date or are now offensive, or no longer accurately reflect its purposes. (6) To change the charity’s purposes.The Charity Commission gives various examples of circumstances in which a charity may wish to change its purposes.[84] For example, the purposes of a charity established to care for people with disabilities may require the charity to provide institutions in which beneficiaries can be housed. The trustees may consider that its purposes should be amended so the charity can provide support for beneficiaries living in their own homes. |

4.2 The ability of charities to change their purposes, and amend other provisions in their governing documents, depends on their legal form. We explained the current law in detail in Chapter 3 of the Consultation Paper; we present a summary here.

4.3 We start by considering the most common forms of corporate charities (charitable companies and CIOs) before turning to unincorporated charities (trusts and unincorporated associations). At the end of this chapter is a table summarising the effect of our proposed reforms. In Chapter 5, we look at charities that are incorporated by (or governed by) legislation or by Royal Charter.

Charitable companies and CIOs

4.4 The articles of association of a company (whether or not it is charitable) and the constitution of a CIO can generally be amended by a resolution of its members at a general meeting.[85] Companies’ articles and CIOs’ constitutions may, however, provide for more restrictive conditions to be satisfied before they can be amended (for example, obtaining the consent of a particular person or the Charity Commission), known as “entrenchment”, but such provision cannot prevent amendment with the unanimous agreement of the charity’s members.[86]

4.5 If the amendment that a charitable company or CIO wishes to make is a “regulated alteration”, then it must obtain the Charity Commission’s prior consent to the change.[87] A “regulated alteration” is:

(1) an amendment to the charity’s purposes;

(2) an alteration to the provisions concerning the distribution of the charity’s property in the event of dissolution; or

(3) any alteration that would authorise a benefit to be obtained by the charity’s directors or members (or connected persons), unless that benefit is authorised by section 185 of the Charities Act 2011.[88]

4.6 We discuss the basis on which the Charity Commission will consent to a change of purposes in paragraphs 4.123 and following.

(1) The company must give notice of the amendment to the Registrar of Companies and provide a copy of the articles as amended, the resolution giving effect to the amendment, and (in the case of a regulated alteration) a copy of the Charity Commission’s consent, all within 15 days of the resolution taking effect.[89] Where the amendment is to the charity’s purposes, the amendment is not effective until it is recorded on the register at Companies House.[90] A failure to notify Companies House of other amendments can lead to criminal liability on the part of the company and its directors, but does not prevent the amendment from being effective.[91]

(2) If the charitable company is registered with the Charity Commission, the trustees must also notify the Commission of the amendment so that the particulars of the charity in the register can be updated.[92]

4.8 The procedure for CIOs is in some ways simpler but also more restrictive. Once a resolution has been passed, the CIO must send a copy of the constitution as amended and the members’ resolution to the Charity Commission.[93] An amendment takes effect once it is registered by the Charity Commission, and the Commission will refuse to register an amendment in certain circumstances.[94]

4.9 Our provisional view was that the regime governing changes by companies and CIOs was satisfactory.[95] Broadly speaking, the rules were supported by consultees. Such charities were considered to have sufficient flexibility to make most changes without having to obtain the Charity Commission’s consent (subject to express entrenchment and provided they are not “regulated alterations”). It was generally considered appropriate that the Charity Commission should have oversight of changes that were regulated alterations, and no consultee suggested that the definition should be significantly expanded or narrowed. Nevertheless, some technical deficiencies were raised by consultees which we now turn to consider.

Differences between companies and CIOs

4.10 CIOs were introduced by the Charities Act 2006 as an alternative to the charitable company; they are incorporated bodies, and the charity trustees and members benefit from limited liability, but the Registrar of Companies is not involved in their registration or regulation. There should, so far as possible, be consistency between the rules governing charitable companies and CIOs. Various inconsistencies were raised by consultees.[96] Some are justifiable, and some extend beyond our terms of reference.[97] We do, however, make a recommendation in respect of one inconsistency raised by consultees.

4.11 Constitutional amendments for CIOs do not take effect until they are registered by the Charity Commission[98] whereas this limitation only applies to companies if the amendment changes its objects.[99] Having to wait until registration for amendments to take effect was said to be unhelpful, unduly limiting and confusing, particularly as there is no process for CIOs to be notified of the exact date on which changes were registered.[100] We can see the potential benefits of the increased Charity Commission oversight of constitutional amendments by CIOs under the current law. The grounds on which the Charity Commission can refuse to register an amendment might ensure that defective or invalid amendments are spotted at an early stage, and before charities purport to rely on them, which might create consequential problems. We also note that CIOs are a new structure – it has only been possible to create CIOs since January 2013[101] – and they are still therefore “bedding in”.

4.12 However, having discussed this issue further with consultees we think that the arguments in favour of aligning the position for CIOs with that for charitable companies outweigh the arguments in favour of greater oversight. First, when possible, consistency between the two regimes is desirable. Greater alignment leaves less room for confusion between the two and therefore less scope for error; it would avoid potential problems arising from trustees of CIOs thinking that, as for companies, amendments take effect from the date of the resolution. Second, we heard from consultees that an important benefit of amendments taking effect immediately (or on a later date specified in the resolution) is that constitutional change can be planned and implemented in an orderly way. It can, for example, coincide with a year-end date or other significant event, such as a change of control of the charity. Allowing amendments to CIO constitutions to take effect from the date of the resolution (or a later date specified in the resolution) will remove barriers to, and complications arising during, constitutional change.

Definition of regulated alterations

4.14 Three consultees[102] raised various difficulties with the three categories of “regulated alterations” in section 198 (for companies) and section 226 (for CIOs) of the Charities Act 2011.

(1) The first category: changes to objects

4.15 Section 198(2)(a) refers to amendments “adding, removing or altering a statement of the company's objects” whereas section 226(2)(a) refers to amendments which would make “any alteration of the CIO’s purposes”. By contrast, the second and third categories of regulated alterations use the same wording. We think that it would be desirable for the definition of “regulated alterations”, so far as possible, to be the same for both companies and CIOs and we recommend a new definition below.

4.16 Consultees also commented that section 198 appeared to include (or reported experiences of it being interpreted as including):

(1) an alteration to the wording of the charity’s objects even if the substance of those purposes remains the same; and

(2) any change to the powers of a charity referred to in the objects cause, even if the objects themselves were not being changed.

4.17 We agree that such amendments should not be regulated alterations. It was also suggested that an amendment to a governing document which would have the effect of altering the charity’s purposes without altering the wording of the objects clause itself might not fall within the current definition. An example was given of an amendment to a defined term, when that term appeared in the objects clause. Charity Commission guidance, however, suggests that such an amendment does fall within the current definition.[103] We agree, and our recommendation would ensure that the substance and not form of the amendment will determine whether or not an amendment is a regulated alteration, thus removing any potential confusion.[104]

(2) The second category: dissolution

4.18 Section 198(2)(b) provides that an amendment to a provision “directing the application of property of the company on dissolution” is a regulated alteration.[105] There was reported to be uncertainty as to whether an amendment that has the effect of overriding a dissolution clause is caught by this definition. The CLA gave the example of the introduction of a power to merge which allows the charity to merge with another rather than dissolve, and therefore the direction in the articles as to what happens to the company’s property on dissolution does not take effect.

(3) The third category: benefits to trustees, members and connected persons

4.20 Sections 198(2)(c) and 226(2)(c) provide that any alteration that would “provide authorisation for any benefit to be obtained by” the charity’s trustees or members, or connected persons, is a regulated alteration. Consultees suggested that it is unclear whether that definition would include an amendment that narrows the circumstances in which benefits can be authorised; the amendment itself does not authorise benefits to be obtained, but the clause as amended does authorise benefits to be obtained. In our view, such an amendment would not be a regulated alteration under the current law. An alteration is only regulated under these provisions if it is the alteration itself which would provide the authorisation for benefits. So if a benefit is already permitted and all an alteration does is reduce the extent of if, the alteration is not authorising a benefit and is therefore not regulated.

Schemes in respect of charitable companies and CIOs

4.21 In the Consultation Paper, we noted that cases in which the statutory powers of amendment could not be used to change the governing document of a company or CIO would be rare, but that in such cases a scheme could be made to amend the governing document.[106] Schemes are legal arrangements, made by the Charity Commission or the court, that change or supplement the provisions that would otherwise apply in respect of a charity or a gift to charity. We discuss schemes in more detail in paragraph 4.37 below.

4.22 Two consultees said that there was uncertainty as to whether the scheme-making power applied in the case of companies and other corporate charities.[107] We accept that the scheme-making power of the court originally depended on the existence of a trust, whereas a charitable company generally holds its property beneficially. But a scheme was made in Liverpool and District Hospital for Diseases of the Heart v Attorney General[108] despite the absence of a trust, and we see no reason to exclude corporate charities from the scheme-making power of the court and Charity Commission.[109]

|

(1) an amendment to a CIO’s constitution by resolution of its members should take effect on the date the resolution is passed, or on a later date specified in the resolution; save that (a) an amendment that makes a regulated alteration should be ineffective unless the prior consent of the Charity Commission has been obtained; and (b) a change of a CIO’s purposes should not take effect until it has been registered by the Charity Commission; (2) the description of changes to a charity’s objects as a “regulated alteration” in section 198(2)(a) be amended to reflect the description in section 226(2)(a); and |

4.24 Clauses 1, 2 and 8 of the draft Bill would give effect to this recommendation.

4.25 We make a further recommendation below concerning the basis on which the Charity Commission should consent to a charitable company or CIO changing its purposes.

Unincorporated charities

4.26 The trust deeds of charitable trusts, and the constitutions of unincorporated associations, can be amended in one of four ways.

(1) Express power

4.27 Trust deeds and the constitutions of unincorporated associations often include express powers of amendment.[110] Such powers might require particular conditions to be satisfied, such as obtaining the consent of the Charity Commission or another person, or securing a resolution of a particular majority of the charity’s trustees or members at a general meeting.

(2) Statutory power to change a small unincorporated charity’s purposes

4.28 Under section 275 of the Charities Act 2011, the purposes of certain small unincorporated charities can be changed by a resolution of the charity trustees.[111] The power applies to unincorporated charities that both (a) have an annual income of up to £10,000 and (b) do not hold “designated land”, namely land held on trusts stipulating that it must be used for the purposes of the charity.[112] The power applies whether or not the governing document contains an express power of amendment; charities with an express power can choose instead to exercise the statutory power.

4.29 To exercise the power, the charity trustees must be satisfied (1) that it is expedient in the interests of the charity for the purposes in question to be replaced, and (2) that, so far as is reasonably practicable, the new purposes consist of or include purposes that are similar in character to those that are to be replaced.[113]

4.30 A copy of the resolution, together with the trustees’ reasons for passing it, must be given to the Charity Commission.[114] The Commission can require the trustees to provide further information, or to publicise the resolution.[115] Otherwise, the resolution will take effect 60 days after it is received by the Commission,[116] unless the Commission objects to the resolution.[117]

(3) Statutory power to amend administrative provisions in an unincorporated charity’s governing document

4.32 Under section 280 of the Charities Act 2011, the charity trustees of an unincorporated charity (regardless of its size or of whether it holds designated land) may pass a resolution to modify any provision in its governing document:

(a) relating to any of the powers exercisable by the charity trustees in the administration of the charity, or

(b) regulating the procedure to be followed in any respect in connection with its administration.[118]

4.34 If the charity is an unincorporated association with a body of members distinct from the charity trustees, the amendment must be approved by at least two thirds of the members at a general meeting.[119]

|

Figure 2: amendments that can be made under section 280 The Charity Commission’s view is that section 280 permits charities to make changes to (amongst other things): · the charity’s name; · the method of appointing trustees; · the number of trustee meetings each year; · the method of appointing the chair; · the quorum provisions; · the criteria for charity membership; and · powers of a third party to appoint trustees (where that third party has ceased to exist or consented to the change).[120] |

(4) Cy-près or administrative scheme

4.37 If an unincorporated charity wishes to amend its governing document but the powers outlined above are not available, then it can apply to the Charity Commission for a scheme to make the amendment sought.[121] As explained in paragraph 4.21 above, schemes are legal arrangements that change or supplement the provisions that would otherwise apply in respect of a charity or a gift to charity. There are two categories of scheme.

(1) “Cy-près schemes” alter the purposes of a charity. “Cy-près” means “as near as possible” or “near to this”, and involves funds being applied for charitable purposes which are similar to the original purposes.

(2) “Administrative schemes” alter any other provisions of a charity’s governing document.

4.38 Cy-près schemes can be subdivided into those that deal with “initial failure” of a charitable purpose, and those that address “subsequent failure”. Initial failure tends to arise in the administration of wills, for example, where a testator has left insufficient funds to carry out the stated charitable purpose. Subsequent failure tends to concern the work of existing charities, for example, a charity’s original purpose is to provide accommodation for people with disabilities, but its beneficiaries would be best served by supporting them in their own homes.[122]

4.39 In the case of initial failure, a cy-près scheme can only be made if the donor has demonstrated a “general charitable intention”.[123] The same does not apply to subsequent failure; if the gift was given outright to a charity, then a cy-près scheme can be made on subsequent failure without having to demonstrate an initial general charitable intention on the part of the donor.

4.40 The power to make administrative schemes is wide; it can be exercised if it is expedient in the interest of the charity to do so.[124] By contrast, cy-près schemes are closely regulated; there are limitations on both the circumstances in which a cy-près scheme can be made and the changes that can be made by a cy-près scheme. Both are explained below.

How does the Charity Commission decide whether to make a cy-près scheme?

(A) Cy-près schemes: the gateways

|