Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

English and Welsh Courts - Miscellaneous

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> English and Welsh Courts - Miscellaneous >> Little v Matthews & Ors [2021] EW Misc 6 (CC) (01 March 2021)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/Misc/2021/6.html

Cite as: [2021] EW Misc 6 (CC)

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

IN THE COUNTY COURT AT NOTTINGHAM

BEFORE MR RECORDER ADKINSON

ON 9 AND 10 SEPTEMBER 2020 and 16 NOVEMBER 2020

JUDGMENT HANDED DOWN 1 MARCH 2021

BETWEEN

MATTHEW LITTLE

Claimant

And

ANDREW MATTHEWS (1)

PETER FLANN (2)

NICHOLAS COOK (3)

HELEN FAIRGRIEVE (4)

Defendants

|

Appearances |

|

|

For the Claimant |

Mr M Rifat, Counsel Instructed by Direct Access |

|

For the Defendants |

Mr P Lakin, Counsel Instructed by JH Powell and Co, Solicitors. |

DECISION

There will be a judgment to the following effect:

The Defendants must pay to the Claimant

1. £9,300 as damages for trespass, and

2. £2,500 as exemplary damages.

If not agreed, the Court will determine questions of interest and costs (and any other ancillary order) after giving each party an opportunity to make submissions.

REASONS

Introduction

3. The claimant, Mr Matthew Little, brings a claim for trespass to land that primarily relates to scaffolding on his land between the 22 June 2018 and 23 August 2018. He claims damages in the order of £98,000 (though in closing appeared to push it toward over £200,000) and exemplary damages. At the start of the hearing, Mr M Little confirmed to the court that he elected his damages to be assessed on the basis of the benefit that the defendants received by the trespass, rather than the loss he actually suffered as a consequence of it (see Ministry of Defence v Ashman (1993) 25 HLR 513 CA).

4. The defendants are a partnership of doctors. I will refer to them as the partnership. They admit trespass on Mr M Little’s land. However, they suggest a figure of just over £1,000 is a more appropriate amount of compensation. They deny the claim for exemplary damages.

Hearing

5. Mr M Rifat, Counsel, represented Mr M Little. Mr Lakin, Counsel, represented the partnership. I am grateful to them for their help in this case and for their submissions.

6. Each Counsel had prepared a skeleton argument. Mr Rifat also prepared a closing note. I have taken their contents into account.

7. There was an agreed bundle of documents and a supplementary bundle. I have considered those documents to which the parties referred me.

8. Although there were some issues about the bundles, notably that they did not appear to be prepared in accordance with the court’s directions, neither party sought an adjournment and both parties adjusted to using them.

9. The claimant himself had produced a bundle because he believed the partnership were in breach of the Court’s order in relation to bundles. However, neither party sought to make reference was made to it during the hearing either in evidence or submissions.

10. On behalf of Mr M Little, I heard oral evidence from Mr M Little himself and from Andrew Little, Mr M Little’s brother and apparent project manager of redevelopment work that Mr M Little was carrying out.

11. On behalf of the partnership, I heard oral evidence from Dr Peter-John Flann, Mr Simon Grattan who was the defendants’ architect and Mr Robin Holmes and who was the foreman of the defendants’ building site.

12. Finally, I heard oral evidence from Anthony Kay, who was a chartered building surveyor and was instructed by both parties as a single joint expert on the issue of licence fees for permission to erect scaffolding on another’s land.

13. Neither the parties, the witnesses or Counsel required any reasonable adjustments.

14. There is a written report from Mr Julian Wilks. He is a surveyor who gave evidence of the letting values of Mr M Little’s property. The report is agreed.

15. I have considered the evidence of all the witnesses.

16. There was an expert report from Mr M Dalley. On 29 March 2019, Her Honour Judge Coe QC refused to allow Mr M Little to rely on it. I pay no regard to it.

17. The hearing proceeded by way of the Cloud Video Platform provided by HM Courts and Tribunal Service. The hearing was initially listed for 2 days on 9 and 10 of September 2020. Unfortunately, due to technical difficulties and because of the fact the hearing was proceeding by way of video link (which experience shows results in hearings usually taking longer), 2 days proved insufficient. Therefore, I heard closing submissions on 16 November 2020 again by Cloud Video Platform.

18. Neither party complained that the use of the Cloud Video Platform or a remote hearing more generally had put them at a disadvantage. I have no reason to doubt that the parties had a fair hearing.

19. I reserved my decision. This is that decision.

Issues

20. In my opinion the following issues arise:

20.1. What is the appropriate basis for assessing the value of the benefit to the defendants that accrued from their trespass?

20.2. On that basis, in in the circumstances of this case what amount of damages should the defendants pay to Mr M Littles for the trespass?

20.3. Have the defendants conducted themselves in a way they calculated to make a profit for themselves?

20.4. If so in the circumstances of this cases should I exercise my discretion to order the defendants to pay exemplary damages to Mr M Little?

20.5. If so, what is that amount of exemplary damages?

Findings of fact

21. On the balance of probabilities, I make the following findings of fact that I believe are necessary for me to determine the outcome of this case.

Background

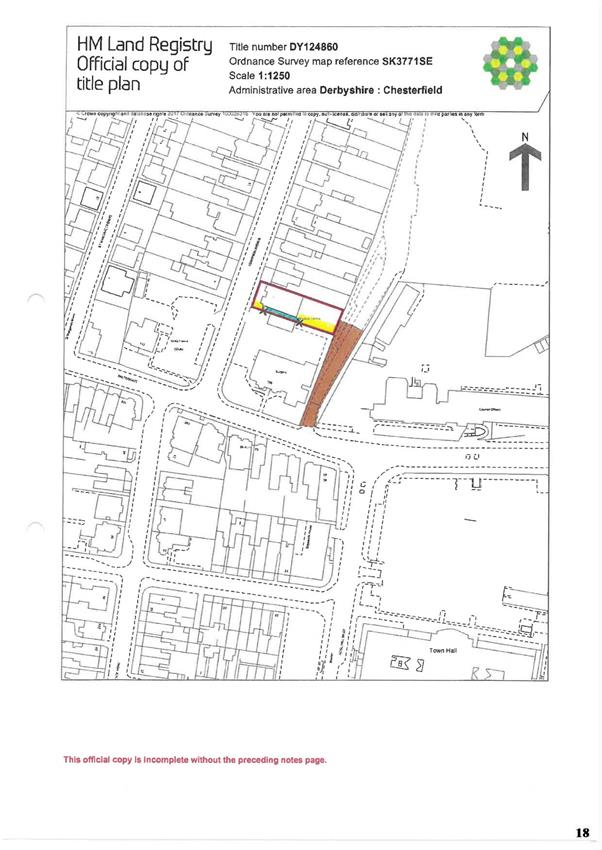

22. Attached to the particulars of claim is a plan labelled “Appendix C”. It is the office copy plan of Mr M Little’s property. I attach it to the judgment.

23. The plan shows the Saltergate and Tennyson Avenue junction in Chesterfield. Tennyson Avenue runs north from Saltergate.

24. On Tennyson Avenue, bounded by the red line is 1 Tennyson Avenue. It appears it was a house that was converted to office use at some point. This is Mr M Little’s property, and he is the sole registered freehold owner. The back of it is an area suitable as a car park. Along its south side is a driveway. This is described as being coloured yellow and green on the plan (though the green appears blue on the copy of plan).

25. Mr M Little also has rights of access to the rear of his property across the land in brown. The Register of Title describes it as follows:

“(13.01.2017) The land has the benefit of a right of way with or without vehicles over the land tinted brown on the title plan. The extent of this right, having been acquired by prescription, may be limited by the nature of the user from which it has arisen.

“NOTE 1: A statutory declaration dated 21 December 2016 made by Paul Stephen Crowther was lodged in support of the claim to the benefit of the right.

“NOTE 2: Copy statutory declaration filed.”

26. I have not seen the statutory declarations. There is no evidence that the right of way is limited in any way meaningful to this case.

27. These areas I will refer to as the “yellow-”, “green-” and “brown land” respectively.

28. The plan marks a part of the border with an “X” at each end. This roughly, but not exactly, corresponds to the boundary between the green land and the land to the south. There was an excavation along the boundary between these two points. I will refer to it as “the excavation”.

29. To the south of 1 Tennyson Avenue and on the corner of Saltergate and Tennyson Avenue is the Defendants’ land. This is a doctors’ surgery that provides NHS services. It is known as the Avenue House surgery. Each of the defendants is a partner in the firm that owns and runs that surgery. It provides NHS general practitioner services to the public. However, as is a common arrangement in the NHS, the partnership is a private business, and it is by running that business at a profit that each partner derives their income.

30. On the plan immediately to the south of the green land there is shown a rectangle. This was an outbuilding I will call “the annexe”. The building was a brick building whose northern wall immediately adjoined to Mr M Little’s driveway and to the green land in particular. The partnership proposed to replace the annexe with another building for education. I will call the replacement “the education centre”.

The partnership’s development

Background

31. Avenue House surgery has about 10,500 patients registered to it. There is a sister-practice with about 3,500 patients.

32. The partnership is funded by NHS fees. The NHS pays a fixed fee to the partnership per patient registered with it. The partnership must provide the services from those fees (and any other special fees that the NHS might pay from time to time).

33. Because of recruitment difficulties and changes in the provisions of services, the partnership had decided to reorganise their practice. They were recruiting non-doctor clinicians (e.g. pharmacists, practice nurses and the like). The partnership also trained those who sought to specialise as general practitioners and they wished to increase those numbers. The partnership also concluded that they needed more managerial space.

The project

34. The project itself consisted of 4 parts:

34.1. Internal redecoration of the existing parts (that the partnership paid for themselves).

34.2. Conversion of the existing surgery’s first floor,

34.3. Addition of a second floor to the existing surgery, and

34.4. Demolition and reconstruction of the annexe and in its stead construction of the education centre.

35. I accept Dr Flann’s evidence that the education centre cost about £200,000 and represented 20% of the total build costs. I also accept the evidence that the progress on the education centre was not integral to the construction or remaining parts of the project or that those other parts depended on it. That is quite apparent from the layout of the site, the details of the application to the NHS for funding and is inherently plausible. Education can clearly be redeployed back into the main surgery where much of it would occur anyway because that is where the patients would be for the most part.

36. I therefore readily accept Dr Flann’s evidence that the education centre was not so integral to the redevelopment that it had to proceed and that in appropriate circumstances they could have abandoned it.

Financing and impact on the partners

37. The partnership bid for funding from NHS England in a competition called the “Estate and Technology Transformation Fund”. If successful they would be able to see more patients and provide significantly more training. Any funding is in the form of grants from the NHS.

38. The funding covered 66% of the build cost and the partnership had to fund the other 34% itself. The area of the project covered by the NHS funding did not receive any rent from the NHS for its use of the premises for 15 years (afterwards it is at commercial rates). The 34% funded by the practice does receive rent from the NHS for the parts the NHS rents.

39. The partnership maintains that they in fact make no profit from the exercise. Dr Flann told me the NHS rent would normally cover the cost of the loans each partner had taken out to fund the project. He suggested to me that the project’s complexity meant in this case the rent does not cover the loans and so the partnership will see a reduction in income. Dr Flann explained if there were an increase in the number of patients (and so the fees paid to the practice) that would be offset by the costs of providing those patients with medical treatment. He also explained that the cost of training and education exceeds the sums paid per student.

40. I have seen the potential costings as part of the bid. They suggest (and Mr Gratton confirms) a cost in the order of £1,100,000. They also suggest the project will result in significantly more consultation rooms.

41. If Dr Flann’s evidence is accepted at face value each partner has decided to take on debt, decrease their own income and increase their potential workload. While I accept that the surgery cannot be seen like a normal business motivated entirely by profit, I reject Dr Flann’s evidence that the project adversely affects the partnership’s finances as he described:

41.1. However, they may see themselves, the partnership is in business to make a profit for the partners. It seems highly improbable that they would bid for and then embark on a £1,100,000 project and take out loans personally to provide a significant part of the finance and do so with the deliberate plan of taking a pay cut or not seeing either an increase in income or capital value of their surgery.

41.2. To that end it seems highly improbable they would not have carried out some financial analysis to see whether it was, in short, worth it. These are intelligent people who would no doubt want to be satisfied what they are personally letting themselves in for financially and the likely benefit of doing so.

41.3. In any case the work has now been carried out and the financial effects would be noticeable in the partnership’s accounts or financial position.

41.4. I would therefore expect that the partnership would have access to documents that show either their preliminary financial analysis or business plan that covers their personal positions and sets out the consequences for them personally of this project; and/or financial accounts that show it had the adverse effect he described. They have not produced that evidence. Dr Flann did not give oral evidence about it either. He would clearly have been in a position to do so. The failure to produce these obvious documents is something that undermines in my mind the partnership’s case on this point.

41.5. Besides, it seems inherently implausible the partnership would embark on such a significant project with significant personal financial risk to make themselves worse off.

41.6. In any case the partnership will own the development afterwards. It would most likely produce a profit given general trends in property prices which it is impossible to ignore. As Dr Flann noted, the partners may retire before the NHS starts to have to pay rent but no doubt the potential for future rent would form part of the calculation of the costs of buying out a partner (or a new one buying in or in any future sale).

42. I conclude therefore the project was undertaken with a view to each defendant making a personal profit. What I cannot assess is what profit they may make because I do not have any figures. Mr M Little has not produced any credible evidence to suggest what profit the partnership might make. I do not accept that the partnership’s failure to provide the details of their financial position means I should conclude that they will make what could be described as significant profits.

43. In my opinion the profit is likely to be modest at best, and far removed from the types of percentages and figures used to describe the profits of property developers, for example. My reasons are as follows:

43.1. On the basis of Dr Flann’s evidence and the bid documents, I accept that the partnership will secure no rent from the NHS for about 15 years in respect of the part they funded. While I believe they will make a profit on the other parts (because it is incredible to think the contrary would be true), the evidence does not support the suggestion this will be significant because this is a surgery in Chesterfield and realistic alternative occupants are unlikely to exist.

43.2. The real profit is the underlying value and expectation of income in 15 years’ time.

43.3. This is not like an ordinary business. This a private business that provides a key state service and it must be common ground (because it is so obvious a feature of public healthcare in the UK) is very tied into the public sector and the National Health Service generally. I do not know the details but do not believe I need to in order for that conclusion to be valid. While they may profit, it clearly going to be nothing like what one might expect from a purely private enterprise.

43.4. I also conclude that I am entitled to accept that the consequence of their close ties to the public health service and its obvious integration with medical education means I am entitled to accept that their motive for the works is not purely profitable. It is also about providing a better service to patients and educational opportunities. Even if they are paid for training, I do accept Dr Flann’s evidence that the training is not purely about money: It is about providing training for future doctors too.

The partnerships’ development

44. The partnership recruited builders and entered into a Joint Contracts Tribunal contract (JCT). Mr Gratton was the contract administrator.

45. The work commenced on 5 February 2018.

46. The project was on a deadline. Mr Gratton in his evidence in chief explained:

“Any delays to the JCT Contract would have resulted in substantial additional costs to the project, and unfortunately, I understand that there was not the flexibility to allow for this due to the part-funding arrangement through the NHS.”

47. The JCT itself contained a provision that if there were delays attributable to the partnership, they would have to pay a penalty of 20% of the contract price (strictly it is not legally a penalty, but I doubt anyone paying it will appreciate the legal nuances).

48. However, Mr Gratton and Dr Flann explained that though there were delays they did not have to pay a penalty. Instead with everyone’s agreement the contract was extended.

Mr M Little’s development

49. Mr M Little purchased 1 Tennyson Avenue with a view to developing it into flats that could be then let out and generate an income for him.

50. One of the ground floor flats was to be for his mother and father. His father provided physical support to his mother who no longer could use stairs. His mother provided emotional support to his father.

51. Mr M Little’s case is that the trespass caused delays in carrying out the works to convert the property to flats. The impact of everything on his parents was they no longer wanted to move into the flat when it was finished.

52. I do not find the evidence about his parents to be persuasive. This is because there is no obvious credible connection between any trespass, delay and their decision. If they needed a ground floor flat, I doubt a delay would have alleviated that need. However, there is credible evidence that urgency compelled them to move elsewhere which might have explained their decision not to move to the flat. It does not really make sense.

53. The remaining property was to be developed into flats that would be let out.

54. Mr M Little also intended to let out the parking spaces at the back of his property to any member of the public who wanted to rent them.

55. Mr Wilks’s said the flats would secure gross £2,415 each month and the parking spaces would secure £480 per month.

56. Mr M Little’s main case is that the trespass impacted on his own project and put it back by approximately at least 14 weeks (they were scheduled for completion in September 2018).

57. To support that he relied on the evidence of Mr Andrew Little, his brother.

58. Mr A Little told me that he lives in London but would travel to Chesterfield at weekends to see how works were proceedings. He told me that Mr M Little had appointed him as a project manager and he would be paid £20,000 per year for that appointment based on a pre-determined level of work.

59. Mr A Little supported Mr M Little’s evidence that the trespass had pushed everything back. He also said he had had to charge an extra £13,779.82 for extra work caused by the trespass. The extra work apparently was the rescheduling of development works, new proposals with the workforce, extra inspections, engaging extra services, dealing with the litigation and need to obtain information for it, confirming accuracy of the details in Mr M Little’s statements and proposing Mr M Little seek damages based on the profit to the defendants.

60. He also explained that Mr M Little had lost rent of £600 per week over 14 weeks, parking revenue of 31 weeks at £100 per week, and another 2 weeks’ rent finding a new excavator (though in fact he had not paid the first contractor). He said that there was an extra cost of £300 for additional utility expenses.

61. His evidence was that because of the trespass Severn Trent had to postpone connecting the property to the water mains.

62. I do not accept that the trespass had anything like the effect that Mr M Little avers. I conclude that Mr M Little has exaggerated the impact significantly. I come to this conclusion for the following reasons:

62.1. Below I have found that the trespass did block the driveway for a time. Against all of this I bear in mind that Mr M Little had a right of way to access the back of his property over the brown land. I accept that was a dispute for a short time with the owner of the brown land, who blocked it off with a concrete ring, but it is quite apparent that it was resolved to allow Mr M Little to gain access again. It was his choice not to use it. Therefore, as a matter of fact the trespasses cannot have had anything like the obstructive effects that he complains of. As Mr Wilks says in the answers to questions on 20 March 2020 in the agreed report

“1. The presence of scaffolding would not have presented access to the rear of the property.”

62.2. Mr A Little is not a project manager by profession. It seems implausible that Mr M Little would retain him as a project manager if he needed one.

62.3. He is though Mr M Little’s brother. While one can have a contractual relationship with a family member, they are not usual. Given

62.3.1. the nature of the role to which he was apparently employed,

62.3.2. the family nature of the relationship,

62.3.3. the significant fee that would be due per annum, and

62.3.4. the precision with which the work he was (and by implication was not) expected to do appeared to be defined by the parties,

I would expect a contract (or at the very least clear written evidence of the existence of an oral contract) to support the arrangement that they say existed. There is none. I find it impossible to accept that there would be no written evidence of such an arrangement. His use of the words “I expect” in is statement which he adopted as his evidence suggest to me it is a moral obligation rather than any legal entitlement that he relies on, which would explain the lack of any contract.

62.4. It is also notable that there is no evidence any payment has been made e.g. like a monthly amount to reflect time already spent, or any payment demanded. There is no explanation why payment of such a large sum would await the end of the project. To my mind the whole of the set-up has an air of unreality.

62.5. There is also no evidence from where such a large sum will come. The maximum possible rent according to Mr Wilks in a year is £34,740 if the flats are rented out and the parking spaces are rented out for 12 months with no loss of income. That seems unlikely (especially as at the time of trial Mr M Little had not rented out all the parking spaces or flats). That is also before any outgoings. I have seen no evidence that shows how Mr M Little accounted for the £20,000 as part of the project’s costs. Such evidence would have been available to him. The fact he chose not to disclose it in my mind undermines his credibility.

62.6. Mr Little’s evidence does not appear to reflect Mr Wilk’s evidence on the availability of the parking spaces. Mr M Little implies none of the parking spaces were available because of the partnership’s trespass. In fact, that is not the case. Mr Wilks says that

“The scaffolding was erected on the side access and not any of the parking spaces, but if used for parking it is envisaged that no more than two spaces would have been covered.”

It seems to me the failure to let out the parking spaces and derive income from them is not because of the trespass but because of a decision on Mr M Little’s part or because there is no market for them.

62.7. Mr Little asserts he has had to charge more but it is not clear why or on what basis.

62.7.1. I would expect having to deal with problems like those caused by the partnership are part of being a project manager because it is by definition managing the project.

62.7.2. Besides there is no evidence of any separate agreement (yet alone enforceable agreement) that shows Mr M Little and he agreed that Mr M Little would pay this extra amount to him.

62.7.3. There is no evidence or explanation of how Mr M Little was going to fund this significant increase.

62.7.4. Overall, I am left with the impression the figures have simply been made up.

62.8. I conclude this is supported by other figures relied on. In evidence Mr Little accepted that the £600 attributed to finding a new excavator is in fact him charging an extra 2 weeks rent waiting for the new excavator, and that he has not had to pay the original excavator. That came out in cross examination and is not how he represented things in evidence in chief. Furthermore, the extra utility expenses are by his own admission a “token gesture” based on the presumption (unevidenced) there would be standing charges.

62.9. I also conclude that support for the fact this is incapable of acceptance derives from what little evidence there is of the arrangements with Severn Trent to connect the flats to the mains water system. Mr Little’s evidence is clear that the trespass

“led to a direct delay in the scheduling of work with Severn Trent.”

62.10. That does not stand up to scrutiny in my opinion. There is only one piece of evidence that shows contact with Severn Trent. It was on 27 July 2018 and is a quote valid for 6 months (i.e. to 26 January 2019) There was no prior inspection before the quote was issued. There appears to be no requirement the work is completed within those six months. There is no evidence that it was a renewal of a quote given already. There is no evidence of when it was accepted. There is no evidence that allows to assess when Mr M Little otherwise expected to seek the quote or have it done (e.g. there is not expected project timeline).

62.11. As it stands it shows when Mr M Little felt he was in a position to take the first formal steps to connecting his property to the water mains. This is near enough right in the middle of the trespass when it is alleged he was unable to work on his property. To me the timing of the quote suggests that the trespass was having minimal effect on the expected progress.

62.12. This is further compounded by when the work was eventually done. It was about 5 months after the trespass ended. The most troublesome part of the trespass was for about 14 weeks. In the circumstances, considering the length of the trespass and the time when Mr M Little sought the quote, the defendant’s actions do not explain the 5 month’ delay. I realise that on accepting the quote Severn Trent must carry out a survey and then do the work. I have noted I do not know when Mr M Little accepted the quote. There is no evidence that they were slower than expected in being able to carry out the survey or works.

63. I am left very much with the impression that Mr M Little and his brother have grossly exaggerated the effect of the trespass on Mr M Little’s project. While the main portion of the trespass clearly had an effect on his use of 1 Tennyson Avenue, its impact on the project was nothing like they have sought to suggest.

The trespass

64. In order to construct the education centre, the partnership’s project required the demolition of the annexe. However, to do this safely required the builders to enter upon Mr M Little’s land, specifically the green land and area around the excavation. To do the demolition and subsequent construction safely required scaffolding on his land. This is because the annexe’s wall was right up to the boundary.

65. It is common ground that the partnership had no right to enter upon Mr Little’s land and there was no legal basis to claim the right e.g. under the Party Walls Act 1996 or Access to Neighbouring Land Act 1992.

66. As part of the project there were regular meetings between Mr Gratton, Dr Flann and the builders. At these meetings they would discuss the problems and options. I readily accept the proposition that Dr Flann made the final decision in all matters and gave instruction on behalf of the partnership. I accept that no trespass would have occurred without his knowledge or consent. To expose a customer to a potential claim like that would be unprofessional to say the least. After considering the manner in which they gave evidence I do not believe Mr Gratton or Mr Holmes came across as unprofessional or that they would expose their client to a claim like this without advising the client and taking the client’s approval.

The first portion of the trespass (April 2017 to 19 February 2018)

67. The trespass actually began in about April 2017 when the partnership’s partners, employees or agents entered on the green and yellow land on foot. It is not clear who actually entered at what time. It was as part of the proposed project. I have no evidence that this itself caused any harm or really interfered with Mr M Little’s enjoyment of 1 Tennyson Avenue.

Correspondence before the main trespass

68. The partnership later tried to seek consent to enter upon and erect scaffolding on Mr M Little’s land. This is evidenced in correspondence between the parties.

69. On 12 October 2017 the partnership wrote to Mr M Little informing him of the proposed works and indicating that they would serve notice under the Party Wall etc. Act 1996 or Access to Neighbouring Land Act 1992 (it is not clear which they intended to rely on - it mentions both).

70. On 20 October 2017 Mr M Little wrote back and said that

“My concerns relating to your development were expressed at the time of the application. In respect of the implementation of the development, I am not able to form a view as to my concerns at this time as I am unsighted as to your plans. Please can you outline your intended development plan and timescales, including timelines. In particular it would be useful to have sight of the ’details and nature of those works’, including the expected timelines for the commencement and completion of works and for the serving of notice.

“Again, I will respond promptly to your letter.”

71. On 28 November 2017 the partnership again wrote to Mr M Little purporting to give a notice under the Party Wall etc. Act 1996 and enclosing a waiver for Mr M Little to complete. In the letter the partnership offered £75 per week that the scaffolding was up. It did not engage with Mr M Little’s letter or the points he raised. I am surprised by that because Mr M Little’s letter strikes me as being a reasonable reply. There is no explanation for the partnership’s delay. Mr M Little’s letter to them was properly addressed. Also this letter is significantly later than the deadline intimated on 12 October 2017. I conclude the partnership received Mr M Little’s letter but ignored it and was carrying on regardless.

72. Mr M Little replied on 8 December 2017. His letter said

“On reading your notice, I would ask that you justify that ‘in order for the works to be carried out properly and for compliance with the legal health and safety requirements of the Construction Design and Management Regulations 2015, it will be necessary for scaffolding and hoarding to be erected on [my] side of the boundary during demolition and whilst the new annexe is being constructed’. Indeed, I have consulted on this matter and I am advised that there are modern building techniques that would avoid the need for you to make such an onerous demand.

“The reason that this is so onerous is that the land that you require provides access to my property. Hence, should you take possession of my land, I would not be able to progress my works nor provide parking for those who may live in the residential property for what appears to be an indeterminate period.

“Further, the sum you determine to be a “reasonable reflection of the scale and scope of the works” would by no means appear appropriate. Indeed, I hope that you appreciate that this is not a matter on money, and I ask that you consider adopting alternative building techniques.

“Should you have any doubt as to the benefits and practicalities- of such techniques I would be happy to put you in touch with appropriate professionals who may be able to advise you further.

“I do hope that at this time you will reconsider your demand.”

73. The letter is properly addressed. I accept Mr M Little posted it and find that the partnership received it. There is no reason to believe they did not.

74. In my opinion this letter is reasonably interpreted as a refusal. However, the tone is not one to cut off any further communication. I come to that conclusion based on the words

“I do hope that at this time you will reconsider” and

“I ask that you consider”.

75. Mr M Little was within his right to refuse, of course. I do not consider his reply was unreasonable. The partnership at this point would be well aware of his position and that they either had to try to press for permission, abandon the part of the project that related to the annexe, or carry on without Mr M Little’s consent.

76. There was no further correspondence after this until 21 February 2018.

The second portion of the trespass (19 February 2018 to 22 June 2018)

77. On 19 February 2018 the partnership’s builders entered onto Mr Little’s land and started the excavation. This involved the demolition of the annexe and the excavation.

78. I have seen photos of the excavation. The excavation itself is to a depth below the level of Mr M Little’s driveway. This caused a part of the driveway to fall in. The difference in level was significant enough to put anyone at risk of injury. Part of the surface of the driveway had crumbled or cracked and in my judgment it was reasonable to presume that the edges of the driveway might continue to crumble under pressure. In what looks like a token gesture, a panel of Heras fencing was rested against the western edge of the excavation leaning into the driveway.

79. I do not accept Mr M Little’s suggestion this made the driveway unusable. Judging by the photographs it would be possible to people to move up and down the driveway and in my opinion for cars and vans to go up and down. I realise that photos can be deceptive, but the photos show the remaining walls along the south side of the driveway which allows some judgment of width. There is a protrusion painted yellow from 1 Tennyson Avenue into the driveway itself which narrows it a bit, but I do not accept the effect of that protrusion or the excavation is to render it useless.

80. I do accept that the excavation made it unsafe for lorries, however. They are wider and heaver. They would be closer to the edge and so risk either the driveway crumbling into the excavation or slipping into it.

81. However, as I note above Mr M Little’s description of the general impact on him of the trespass is nothing like he described. In any case he had a right of access to the rear of his land over the brown land.

82. Because no trespass would have occurred without the partnership’s consent, and because they would have known their limited options in December, I conclude the partnership consciously decided to carry out this trespass. They knew they did not have consent. They had obviously chosen not to abandon the redevelopment of the annexe. Conscious and deliberate trespass was their only alternative.

Further correspondence

83. The partnership’s solicitors then write on 21 February 2018 seeking access under the Access to Neighbouring Land Act 1992 and intimating an application to the Court in the absence of Mr M Little’s agreement. While they offered to pay compensation, they did not this time propose an amount.

84. The letter is properly addressed, and I am satisfied Mr M Little received it at that address. He did not reply.

85. The timing of the letter is curious. The trespass had already started. Because they knew they did not have permission but had chosen to proceed nonetheless, the reasonable conclusion is that they deliberately used the fact there was a trespass to try to coerce an agreement. If it were otherwise, they would have written this letter in advance.

The main trespass (22 June 2018 to 24 August 2018)

86. The trespass that is significant for this claim began on 14 June 2018 (but Mr M Little in his claim complains only about the trespass from 22 June 2018).

87. On about 14 June 2018 the partnership’s builders entered onto Mr Little’s land and erected scaffolding. They did this to enable them to demolish the annexe.

88. I have seen photos of the scaffolding. The scaffolding footprints and the fencing are entirely on Mr M Little’s land. The scaffolding completely blocks the drive across the green land. It is not possible to pass under it because, for safety reasons, it is fenced off with Heras fencing.

89. He would not be able to use the driveway but would be able to use the brown land instead. Therefore, I am satisfied that the impact was not such to prevent access to the rear of his land either on foot or by vehicles.

Correspondence about the scaffolding

90. Correspondence then followed between the parties. I set out the key points.

91. On 25 June 2018, 10 July 2018, 18 July 2018amd 20 July 2018 Mr M Little complained personally and later through solicitors about the scaffolding and demanding its removal, citing the impact on his ability to do works on his property. The latter correspondence threatened injunction proceedings.

92. On 6 July 2018 and 20 July 2018, the partnership replied through its solicitors. They intimated they would resist any application for an injunction because damages would be adequate. The letter said that Mr M little was incorrect in his correspondence to cite the Party Wall etc. Act 1996 in support of his case, not noting the irony that it was the partnership themselves who first sought to rely on it. They wrote:

“Turning to the issue of the scaffolding on your client’s land, my clients have previously apologised for the presence of this which regrettably is unavoidable.

“…

“In light of your threat to apply for an injunction, please note that we have taken the liberty of obtaining informal advice from Counsel … who has confirmed that in his view it is extremely unlikely that the court would consider an injunction to be appropriate in all the circumstances outlined above.

The letter then threatened a cross-application under the Access to Neighbouring Land Act 1992.

93. In my view the correspondence demonstrates the partnership made a deliberate decision to trespass in this way on Mr M Little’s land because they believed the benefit to them outweighed the risk of compensation to Mr M Little. My reasons are as follows:

93.1. I have already noted the builders would not have carried out any trespass without the partnership’s consent. Because of the regular project meetings and professionalism of the builders and Mr Gratton it is inconceivable the partnership was not aware of the need for the trespass if the annexe was to be rebuilt as the education centre. They must have consented to it. This is supported by Dr Flann’s evidence which was equivocal to say the least on this issue. I would expect the conversations about this part of the project to be clear in his mind given the results of it, but he was vague instead. If the partnership had not been consulted about it, one would expect there to have been a row with the builders and Mr Gratton about how they put the partnership in this situation. There is no such evidence of any such exchange.

93.2. The options were negotiate, abandon or proceed. The partnership clearly did not seek to continue negotiation. It is also the case the partnership did not consider abandonment as a realistic alternative. Their solicitor’s letter of 20 July 2018 letter must have been written on instructions. There is no suggestion otherwise. The use of the words

“regrettably is unavoidable”

support the proposition abandonment was not in the partnership’s mind an acceptable alternative to trespassing with the scaffolding and carrying on regardless because, as a matter of fact, plainly the option of abandonment meant the trespass was avoidable.

93.3. Furthermore, the letter’s reference to Counsel’s informal advice and their obvious decision to continue with the trespass leads me to conclude that, if not before, they knew by this point they were in the wrong but deliberately felt the benefit to them would outweigh any legal consequences of their trespass. If they felt otherwise, they would have instead ceased their trespass.

94. Because the partnership was going to profit from these works to their surgery, it must be the case that the proposed education centre provided some of that profit. That is a reasonable inference, and the partnership has adduced no evidence to suggest it would be a “loss leader” part of the project.

95. Eventually Mr M Little issued an application for an injunction. Due to a lack of court resources the application could not proceed before the scaffolding was taken down on 24 August 2018. However, it must have been clear by now that they did not have consent from Mr M Little. They opposed the application for an injunction. The partnership therefore must have decided to oppose the injunction because they felt continuation outweighed any potential adverse legal consequences of their trespass.

The final portion of trespass (24 August 2018 to 23 September 2018)

96. The partnership’s builders removed the scaffolding that completely blocked the drive on 24 August 2018. Counting from 22 June 2018, the scaffolding blocked the driveway for 9 weeks.

97. The scaffolding was not removed completely, however. Instead, the partnership’s builders left up scaffolding along the northern wall of the new education centre and protruding at the back over Mr M Little’s land.

98. Photographs show the scaffolding in place.

98.1. Along the driveway it comes out from the wall approximately 1 metre (it appears). At the first level of the scaffolding above ground there extends some poles across the driveway. There is at the western end some Heras fencing with its foot to hold it in place that protrudes into the driveway.

98.2. The effect is that a person can walk up and down the driveway and pass with things like a wheelbarrow or pallet truck. However, it is impossible for any car or bigger to get along the driveway.

98.3. At the rear there protruded over the car park area 2 poles. While the photo is at an angle and so it is difficult to judge, it seen they are roughly the height of the second floor of Mr M Little’s building.

98.4. However, the car park has 2 pieces of Heras fencing in place in a V-formation about 2 further pieces of scaffolding that protrude over the car park. I am satisfied these are much closer to the ground and I believe one can estimate they are about 2 metres at most above the ground and, judging by the photos extend about 1 to 1.5 metres into the car park air space. The fact that the partnership’s builders put Heras fencing here forming a V about these protruding pieces of scaffolding strongly implies they felt there was a risk of them being hit with a consequent risk of damage or injury because they overhung and because of their proximity to the ground.

98.5. Mr Wilks says this did not cover parking spaces but would have taken up the equivalent space of 2 parking spaces. The photographs support this.

99. Mr M Little still had access to the rear of his property over the brown land. Mr M Little said the presence of the scaffolding stopped him using a digger to effect his works. Undoubtedly if he needed to dig in the vicinity of the scaffolding it would have meant he could not use his digger. However as explained above I am not satisfied that his own works were intended to proceed how he alleged. There was nothing to stop him working within the property or on its exterior. In my judgment this period of trespass had limited impact on his own works.

100. The scaffolding was removed completely on 23 September 2018 (4 weeks and 3 days later).

Expert evidence on the licence fees

101. Mr Kay gave evidence on potential licence fees. I am quite satisfied that Mr Kay has done his best to assist the Court. However, I have found his evidence in fact to be of little actual assistance. I do not mean this as a criticism of his expertise personally. The tenor of his evidence was it was an educated guess on his part and that he felt that was really the best anyone could do.

102. The reason I found his evidence of little assistance is because of his principal conclusion, where he said:

“a licence fee towards the upper end of the range £150 to £7,000 per week would not have been unreasonable.”

That is such a broad range of potential values as to present little help whatsoever.

103. It is clear that the upper end value is predicated on the impact of the trespass being entirely as described by Mr M Little. He, rightly, did not express a view on the credibility of Mr M Little’s position.

104. However, in evidence Mr Kay told me the following matters which help to refine his evidence somewhat:

104.1. His rationale was based on the fact that Mr M Little had the partnership “over a barrel” and therefore he could demand what he liked;

104.2. The partnership faced a penalty under the JCT contract of 20% of the contract value (£200,000) if there were delays so that put them under extra pressure;

104.3. My Kay said in his report:

“4.18 The upper limit of any fee will be an amount above which the developer no longer finds it commercially viable to proceed. In such a circumstance, an agreed fee might be based upon sharing of the anticipated overall development profit with the licensor. The principle is analogous with the concept of ‘ransom strips’.”

104.4. His only recent experience of negotiating a licence fee for scaffolding on someone else’s land resulted in a weekly fee of £575. However, he felt that it is not easy (or safe to compare one site to another - there is no standard rate).

104.5. If there were no development profit from the partnership’s project, one might expect a fee of between £50-£150 per week.

104.6. In reply to the question:

104.7. “6. If you were to negotiate the access rights to the neighbouring land for the Claimant, what is the price a reasonable Claimant would demand for the Defendants’ right to use the land….?”

Mr Kay said

“The question [in the letter of instructions] put qualifies the nature of the negotiating Claimant with the word ‘reasonable’. I am not aware of any legal requirement for such a potential licensor to possess that quality. However, within that constraint, and excepting time, contract, or other commercial pressures on a potential licensee, I would advise that a scaffold licence fee of between £150 and £300 per week might be reasonable, in addition to any cost to the licensor of delaying, accelerating or postponing his own works to take account of the presence of the scaffold.”

104.8. As I read this it appears therefore his maximum figure of £7,000 is premised on the claimant not being reasonable because the report does not suggest one could reasonably attribute a cost to the claimant of £6,600 per week (i.e. the difference between the £300 maximum reasonable fee and £7,000 maximum in his conclusions).

The law

105. Despite the starkly different positions on the outcome, the parties appear to agree on many principles as to the law. The parties have referred me to many cases. I have taken them all into account. For brevity however I have referred only to those that I believe are necessary to explain what I understand the law to be and to explain my decision. I emphasise that while I will not refer to every case, I note that those of the senior courts and senior judiciary involve a detailed and thorough inquiry into the previously decided cases, including some that were cited to me but which I have not set out below. There is nothing useful I can add to their words.

Damages for trespass

The correct measure

106. The partnership suggest that the correct measure of damages is market rental value for the period of wrongful occupation. They cite in support McGregor on Damages 20th ed [39-046] and Inverugie Investments Ltd v Hackett [1995] 1 WLR 713 UKPC.

107. I do not believe that this is a correct statement of the law as now understood. I come to that conclusion because in Attorney General v Blake [2001] 1 AC 268, [2000] UKHL 45 Lord Nicholls said at 279:

“A trespasser who enters another’s land may cause the landowner no financial loss. In such a case damages are measured by the benefit received by the trespasser namely by his use of the land. The same principles are applied where the wrong consist of use of another’s land for depositing, or by using a path across the land or using passages in an underground mine. In this type of case the damages recoverable will be in short, the price a reasonable person would pay for the right of user [my emphasis throughout].”

108. The principle of a price a reasonable person would pay has been identified as the hypothetical licence fee that the partnership would negotiate with and then pay to Mr M Little. This has been applied in a number of cases since in both the High Court and the Court of Appeal.

The relevant considerations.

109. In Wynn-Jones v Bickley [2006] EWHC 1991 (Ch) His Honour Judge David Hodge QC (sitting as a High Court Judge) was considering damages in lieu of an injunction. The details do not matter except that the trespass was permanent and not temporary like in this case before me. His Honour Judge Hodge said:

“[49] There is a useful enumeration of the factors to be taken into account at [Snell’s Equity 31 ed [18-018]], the passage referred to by Neuberger LJ in [Lunn Poly Limited v Liverpool & Lancashire Properties Limited [2006] EWCA Civ 430 ] to which I said that I would return. Where the defendant’s obligation is not to do a thing, the value of Mr M Little’s right to performance is the value of being able to stop the defendant from doing that thing. The thing must be identified with precision before it can be valued. In the present case the thing is the ability to prevent an encroachment in the form of an extension to the Wynn-Jones’ garage, trespassing upon Mrs Bickley’s land.

“[50] The learned editors (that is of Snell) go on to say that the market value of a right in that nature will not normally be readily identifiable, but even so, the value of the thing is essentially a matter of fact and is therefore to be determined upon the evidence. The learned editors continue:

“ There are few cases in which the process of valuation has been considered, but it is suggested that the following principles are of general application in way leave cases:

“ 1. The correct valuation date will normally be the date when the breach is committed or, if the breach has not been committed at the date of trial, the trial date.

“ 2. The actual conduct of the parties is irrelevant.

“ 3. The valuer proceeds on the assumption that the price has been negotiated between a willing grantor and a willing grantee, each of whom is looking to agree a proper price for the grant but not a large ransom.

“ 4. It is to be assumed that the hypothetical parties would put forward their best points in the negotiations.

“ 5. Those negotiations would have taken place before the transgression occurred.

“ 6. The basis of negotiation would be a split of the defendant’s gain, although that gain would not have been obvious and would have been the subject of debate.

“ 7. The negotiating parties are to be assumed to know all such things as real people in their position would have been able to discover.

“ 8. The price so identified must feel right.”

“[51] In my judgment, that is an accurate, albeit not exhaustive, statement of general principle.”

110. The approach was applied in Sinclair v Gavaghan [2007] EWHC 2256 (Ch) , though Patten J cautioned the need to remember the difference between a permanent and temporary trespass, and set out the key issues to resolve. He said that:

“[16] One obvious and important difference between cases such as [Wrotham Park Estate Co Ltd v Parkside Homes Ltd [1974] 1 WLR 798 EWHC(Ch)] and the present one is that the court was there assessing compensation to be awarded in lieu of an injunction and therefore to compensate Mr M Little for a continuing and permanent invasion and loss of its rights. Without a notional relaxation of the covenant, the developer had no right to build at all. In this case, the award of damages is limited in time to the period from when use of the Red Triangle began until at latest, the grant of the interim injunction on 6 January 2006. In principle, however, I can see no reason why the model developed in cases such as Wrotham Park should not be adapted and applied to the present case provided that one bears in mind the more limited nature of the exercise and takes into account the considerations which would have been relevant to negotiations for the limited permission being sought. [my emphasis]. This approach is consistent with the decision in Ashmore [sic. I believe it is a reference to Ashman from context] (as approved in Blake) that the court is seeking to ascertain the value to the Defendants of their unauthorised use of Mr M Littles’ land. What therefore needs to be determined is:

“ (i) What the acts of trespass were;

“ (ii) What were their purpose and effect in relation to the development of the Yellow Land: and

“ (iii) What alternatives did the Defendants have to using the Red Triangle in order to carry out those works.”

111. Sinclair concerned a trespass a small triangular piece of land (the so-called Red Triangle). The trespass involved passing through Mr M Little’s land as a convenient way of delivering materials to the defendant’s site during a period when an access road was being constructed. The trespass took place over a period of three months. The trespass occurred through convenience not necessity. Mr M Littles sought £125,000. Patten J awarded instead £5,000.

112. The Court of Appeal approved Sinclair in:

112.1. Enfield LBC v Outdoor Plus Ltd [2012] 2 EGLR 105 EWCA and

112.2. Eaton Mansions (Westminster) Ltd v Stinger Compania De Inversion S.A [2014] HLR 4 EWCA.

113. In Enfield LBC, Henderson J said at [47]:

“The starting point is the admitted trespass which took place for nearly five years, and the function of the hypothetical negotiation is to ascertain the value of the benefit of that trespass to a reasonable person in the position of Outdoor or Decaux. As Vos J said in Stadium Capital Holdings at [69] [which I refer to below], the value of that benefit is

“ ‘the price which a reasonable person would pay for the right of user, or the sum of money which might reasonably have been demanded as a quid pro quo for permitting the trespass’.

“For that purpose, it has to be assumed that the hypothetical negotiation would have resulted in an agreement, even if the parties might in fact have refused or been unwilling to agree. It also has to be assumed that the actual trespass which has occurred would in fact take place, because the whole point of the exercise is to reach a reasonable measure of compensation to Mr M Little for that trespass.”

114. In Eaton Mansions (Westminster) Ltd the Court was concerned with a company that owned 2 flats in a block and had installed air conditioning units. They had been removed by the time of trial. The Court addressed the relevance of events that occurred after the valuation date. Patten LJ said:

“[18] Neuberger LJ [in Lunn Polly Limited], differing in this respect from what Mr Anthony Mann QC had decided in AMEC Developments Ltd v Jury’s Hotel Management (UK) Ltd (2001) 82 P&CR 22, [2000] EWHC Ch 454, considered that, as a general rule, post-valuation events should not be taken into account:

“ [27] It is obviously unwise to try and lay down any firm general guidance as to the circumstances in which, and the degree to which, it is possible to take into account facts and events which have taken place after the date of the hypothetical negotiations, when deciding the figure at which those negotiations would arrive. Quite apart from anything else, it is almost inevitable that each case will turn on its own particular facts. Further, the point before us today was not before Brightman J or before Lord Nicholls in the cases referred to by Mr Mann

“ [28] Accordingly, although I see the force of what Anthony Mann QC said in paragraph 13 of his judgment, it should not in my opinion be treated as being generally applicable to events after the date of breach where the court decides to award damages in lieu on a negotiating basis as at the date of breach. After all, once the court has decided on a particular valuation date for assessing negotiating damages, consistency, fairness, and principle can be said to suggest that a judge should be careful before agreeing that a factor which existed at that date should be ignored, or that a factor which occurred after that date should be taken into account, as affecting the negotiating stance of the parties when deciding the figure at which they would arrive.

“ [29] In my view, the proper analysis is as follows. Given that negotiating damages under the Act are meant to be compensatory, and are normally to be assessed or valued at the date of breach, principle and consistency indicate that post-valuation events are normally irrelevant; but, given the quasi-equitable nature of such damages, the judge may, where there are good reasons, direct a departure from the norm either by selecting a different valuation date or by directing that a specific post-valuation date event be taken into account.”

“[19] This view has been subsequently approved by Lord Walker in the Privy Council case of Pell Frischmann Engineering Ltd v Bow Valley Iran Ltd [2011] 1 WLR 2370 at [50].”

115. At [23] Patten LJ emphasised the hypothetical fee is limited to what the defendant would have paid and is not a measure of the loss of claimant’s opportunity to negotiate a fee.

116. In Stadium Capital Holdings (No.2) Ltd v St Marylebone Property Company & Anor [2012] 1 P&CR 7 EWHC(Ch) Vos J carried out a thorough review of the authorities, including many that were cited to me. He summarised the approach as follows:

“[69] In the light of these authorities, it seems to me that, in a trespass case of this kind, “hypothetical negotiation damages” of the kind described in these cases are obviously appropriate. That negotiation is taken to be one between a willing buyer and a willing seller at an appropriate time (in this case accepted to be when the trespass began). Events after the valuation date are generally ignored. The fact that one party might have refused to agree is irrelevant. But the fact that one party held a trump card and could have stopped the defendant obtaining any benefit is a relevant matter. The value of the benefit of the trespass to a reasonable person in the position of the particular defendant is what is being sought. In other words, the price which a reasonable person would pay for the right of user, or the sum of money which might reasonably have been demanded as a quid pro quo for permitting the trespass.”

117. Stadium Capital Holdings (No.2) Ltd concerned a case with an advertising hoarding. It was a pure commercial arrangement. Vos J concluded that appropriate remedy was 50% of the expected profit generated by the advertising hoarding.

118. Drawing it together it seems the principles are as follows:

118.1. What are the relevant acts of trespass?

118.2. What were the

118.2.1. Purpose, and

118.2.2. effect

of the trespass in relation to the development of the defendants’ land?

118.3. What alternatives did the defendants have?

119. When assessing the hypothetical licence fee that the parties would negotiate, and the partnership would pay to Mr M Little:

119.1. The correct valuation date will normally be the date when the trespass began.

119.2. The actual conduct of the parties is irrelevant.

119.3. I must assume that Mr M Little is a willing grantor and the defendants a willing grantee.

119.4. I must presume Mr M Little is not seeking a large ransom.

119.5. I must presume the hypothetical parties would put forward their best points in the negotiations.

119.6. Those negotiations happened before the trespass started.

119.7. The basis of negotiation would be a split of the defendant’s gain, although that gain would not have been obvious and would have been the subject of debate.

119.8. The parties knew all such things as real people in their position would have been able to discover.

119.9. The fee identified must feel right.

119.10. Events after the valuation date are generally ignored.

119.11. It is irrelevant one party might refuse at all.

119.12. It is relevant if one party held a trump card and could have stopped the defendant obtaining any benefit.

119.13. My focus should be on value of the benefit of the trespass to a reasonable person in the position of the particular defendant that is being sought. i.e. what the reasonable person would have paid.

Exemplary damages

120. So far as relevant to this claim, I can only award exemplary damages if I am satisfied that Mr M Little’s case falls in the second category as described by Lord Devlin in Rookes v Barnard (No.1) [1964] AC 1129 at 1126

“Cases in the second category are those in which the defendant’s conduct has been calculated by him to make a profit for himself which may well exceed the compensation payable to the plaintiff. … It is a factor also that is taken into account in damages for libel; one man should not be allowed to sell another man's reputation for profit. Where a defendant with a cynical disregard for a plaintiff's rights has calculated that the money to be made out of his wrongdoing will probably exceed the damages at risk, it is necessary for the law to show that it cannot be broken with impunity. This category is not confined to moneymaking in the strict sense. It extends to cases in which the defendant is seeking to gain at the expense of the plaintiff some object—perhaps some property which he covets—which either he could not obtain at all or not obtain except at a price greater than he wants to put down. Exemplary damages can properly be awarded whenever it is necessary to teach a wrongdoer that tort does not pay.”

121. In Axa Insurance UK Plc v Financial Claims Solutions Ltd [2019] RTR 1 EWCA (which concerned fraudulent claims based on fake accidents that the defendant had made against the insurers) Flaux LJ said:

“[30] At [43] of his judgment [in Borders (UK) Ltd v Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis [2005] Po LR 1 EWCA], Rix LJ said:

“ ‘Exemplary damages ... are not to be contained in a form of straight-jacket, but can be awarded, ultimately in the interests of justice, to punish and deter outrageous conduct on the part of a defendant. As long therefore as the power to award exemplary damages remains, it is not inappropriate in a case such as this, where the claimants have been persistently and cynically targeted, that they, rather than the state, should be the beneficiaries of the court’s judgment that a defendant’s outrageous conduct should be marked as it has been here. They are truly victims, and, for the reasons given by Master Leslie himself, there is no question at all of the award becoming a mere windfall in their hands.’

“[31] Provided that it is recognised that the criterion which Lord Devlin identified, that the wrongdoer has calculated that the profit to be made from the wrongdoing may well exceed any compensation he has to pay the claimant, must have been satisfied for exemplary damages in the second category to be available, this seems to me to be an appropriate statement of the approach to be adopted to the award of exemplary damages in this category.”

122. I should bear in mind the compensatory award itself and only award exemplary damages if they are inadequate: Rookes.

123. The compensation for exemplary damages must be moderate in accordance with the overall facts of the case and in light of the conduct and need to mark disapproval: Daley v Mahmood (2005) 1 WLR 1 HC(QB).

124. The defendant’s means are of some relevance (though not necessary the claimants): see Rookes and Rowlands v Merseyside Chief Constable [2007] 1 WLR 1065 CA.

Conclusions

Compensation for trespass

125. There appear to be 4 period of trespass:

125.1. From April 2017 to 19 February 2018;

125.2. 19 February 2018 to 22 June 2018;

125.3. 22 June 2018 to 24 August 2018

125.4. 24 August 2018 to 23 September 2018

126. In each portion of the trespass the partnership’s purpose was to progress the redevelopment of the annexe into the education centre. While this is part of the overall project to redevelop their surgery, it is plainly a separate and severable part. The trespasses had no connection with and no effect on the other parts of the partnership’s project.

127. The purpose of the redevelopment was to increase the partnership profit, but the following were also equally significant factors: to promote education and better services at the surgery for the benefit of NHS patients. This was not purely about profit.

128. The effect of the trespass on the partnership was that they were able to complete the redevelopment of the annexe into the education centre. The only alternative was to continue to negotiate or not to proceed with the project.

129. The trespasses had the following effects on Mr M Little

129.1. From April 2017 to 19 February 2018 there was no appreciable effect on Mr M Little.

129.2. From 19 February 2018 to 22 June 2018 it meant that he was unable to manoeuvre lorries down the driveway.

129.3. From 22 June 2018 to 24 August 2018 he was unable to use his driveway at all;

129.4. From 24 August 2018 to 23 September 2018, vehicles could not use his driveway and part of the car park was unusable.

129.5. However, at all times Mr M Little retained access to his property through the building’s front and back doors and he had access to the rear of his property across the brown land. The trespass did not stop him proceeding with his works. In fact, as I found the trespass actually had limited practical impact on his own building project.

130. I do not believe it is proper to consider the trespass to which the hypothetical fee relates as beginning in April 2017. The impact was minimal to non-existent it seems. That would ordinarily warrant only an injunction and nominal damages. I do not believe a reasonable person in Mr M Little’s position would have demanded a fee even if he had the “trump card” simply to allow people working on a project next door to walk on his land. I would ordinarily award nominal damages for this period, but I believe the final award will represent adequate compensation for this period of trespass too.

131. Therefore, the correct valuation date in my opinion is the period commencing 19 February 2018.

132. I must then consider for how long the trespass occurred or whether the periods should be sub-divided to reflect the different incursions. I have decided that they should not be subdivided. Instead, it should be treated as a whole period of one trespass from 19 February 2018 to 23 September 2018 (31 weeks). My reason is that while the level of incursion varies considerably, I am to calculated damages on the basis of a hypothetically negotiated fee. I accept in principle a fee could be graduated by reference to expected levels of incursions over a period of time. However, I have no evidence that allows me to say these levels of incursions were entirely in accordance with the levels and durations expected (there is a project timeline, but I do not accept it shows sufficient detail). Secondly there is no evidence to show it is a usual practice or that the builders in this case would appreciate it. In fact, being told that one may have only one level of incursion to date X and then another to date Y strikes me as superficially inconvenient. If the redevelopment of the annexe required 31 weeks of trespass on Mr M Little’s land, the reasonable negotiation would have been for a licence for those 31 weeks, and the builders would then have put up as much or little scaffolding as they liked. I therefore reject the idea that the compensation for the period 19 February 2018 to 22 June 2018 should be lower or that from 24 August is should be limited to 2 parking spaces.

133. Considering the facts and the presumptions that the law requires me to make, I believe that Mr Kay’s suggested figure of £300 per week for 31 weeks does justice in this case. The key factors that point toward this are

133.1. Mr M Little held the “trump card”.

133.2. Mr M Little on the other hand was not going to be adversely affected by the incursion because he had access over the brown land and his project was running to a much later schedule as demonstrated by the date for installation of the water supply.

133.3. The partnership had no choice but to negotiate in order for their project to proceed. Abandonment was theoretical a possibility but not the facts show something they would not countenance.

133.4. The partnership’s project had with it an element of profit but there was also a non-financial element too.

133.5. The fee of 31 weeks × £300 per week = £9,300 feels right. It is an amount that a reasonable person in the partnership’s position would have paid.

133.6. I am satisfied that this also encompasses adequate compensation for the trespass from April 2017 to February 2018.

134. Therefore, for trespass I award the sum of £9,300.

Exemplary damages

135. The first question is whether the trespass was done in a way calculated to make a profit.

136. I have found as a fact that the partnership was going to profit from the work turning the annexe into the education centre. I concluded this was at least part of their motive to press ahead knowing they did not have permission from Mr M Little to erect scaffolding. They knew there would have to be a trespass. I concluded later that their reaction to the injunction proceedings supports the conclusion that they decided the potential reward outweighed the risk of any compensation payable, so it was worth them proceeding nonetheless.

137. I conclude this is sufficient to demonstrate that the partnership had calculated that the profit to be made from their trespass might well exceed any compensation payable.

138. Considering the case overall I do not believe the compensatory award for trespass itself is sufficient to mark the court’s disapproval of

138.1. the partnership’s decision to incur on Mr M Little’s land knowing full well they had to in order to complete the redevelopment of the annexe and that he had refused permission.

138.2. The decision to continue it when injunction proceedings were intimated because the damages that might be payable were outweighed by any benefit they would accrue from completion.

139. The question therefore next is the amount. The following factors I believe are relevant:

139.1. The understanding the partnership had from very early on that they did not have permission to make the incursions onto Mr M Little’s land, but their decision do to so nonetheless because this part of the project was profitable.

139.2. The partnerships implications that it had rights under the Party Wall etc. Act 1996 and/or Access to Neighbouring Land Act 1992 which it did not. While initial reference to the Act is understandable, their reference through solicitors to the 1992 Act in July 2018 is not and appears to be an assertion of a right they should have known they did not have.

139.3. The partnership’s conscious decision to carry out the trespass when there was the alternative of seeking further negotiation or abandonment shows a conscious decision to trespass and shows they through the risk was worth the consequences.

139.4. The partnership’s conscious decision to oppose the injunction shows they clearly felt by that point the compensatory element was worth risking against the lost profit from stopping and ceasing the trespass.

139.5. While there is a calculated attempt to profit, I believe I must bear in mind the other factor that there was an equal motivation about providing education facilities for future doctors and improving services to NHS patients generally, and that while a private enterprise it is very much a provider of public services within a framework set out by the government and therefore the partnership is in not comparable to say a property developer.

139.6. The partnership will profit but that is in the value of the land and the expectation of rent in 15 years’ time. The profit therefore is only a “paper” profit and in the immediacy, I am satisfied it is limited in amount.

140. Considering the above factors and the need for modesty, I believe an award of £2,500 in exemplary damages is sufficient to mark the Court’s disapproval of the partnership’s conduct and to compensate Mr M Little accordingly.