Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

England and Wales High Court (Technology and Construction Court) Decisions

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> England and Wales High Court (Technology and Construction Court) Decisions >> EE Ltd v Avanti Broadband Ltd [2025] EWHC 1160 (TCC) (10 October 2025)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/TCC/2025/1160.html

Cite as: [2025] EWHC 1160 (TCC)

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

Neutral Citation Number: [2025] EWHC 1160 (TCC)

Claim No: HT-2025-000085

IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE

BUSINESS AND PROPERTY COURTS OF ENGLAND AND WALES

TECHNOLOGY AND CONSTRUCTION COURT (KBD)

Date: 15 May 2025

B e f o r e :

MR JUSTICE WAKSMAN

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Between:

|

|

EE LIMITED |

Claimant |

|

|

- and - |

|

|

|

AVANTI BROADBAND LIMITED |

Defendant |

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Matthew Lavy KC and Daniel Khoo (instructed by CMS Cameron McKenna Nabarro Olswang LLP, Solicitors) for the Claimant

Matthew Parker KC and Ian McDonald (instructed by Jones Day, Solicitors) for the Defendant

Hearing date: 7 May 2025

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

JUDGMENT

INTRODUCTION

1. This is an application made by the Claimant, EE Ltd (“EE”), for interim injunctive relief against the Defendant, Avanti Broadband Ltd (“Avanti”). The essence of the relief sought is that Avanti must not suspend or otherwise withdraw or materially change the satellite mobile backhaul services that it is providing to EE, until trial or further order.

2. Paragraph 2 of the draft order then provides for payment to Avanti for the continued provision of such services at a pro-tem price to be determined by the Court, which would be subject to final resolution at a later stage.

3. EE’s underlying case is that there remains on foot as between it and Avanti, an underlying contract pursuant to which Avanti has been providing the relevant services since July 2016. It therefore follows that there is an extant contractual obligation upon Avanti, going forwards, to continue to provide them on the basis that the relevant contract has not thus far been terminated.

4. The reason for EE seeking the injunction is that since early this year, Avanti has threatened to withdraw its services on a phased basis unless EE agrees to pay for those services at a substantially increased rate which EE contends is exorbitant and unreasonable and which it is not bound to pay. It is common ground that Avanti has indeed intimated that it will start to withdraw it services unless agreement on price can be reached.

5. The present position is that Avanti has been prepared to continue to provide its services pending the making and outcome of this application. Further, it has made an open offer to EE to continue providing them for a further 3 months but no longer and at the higher rate which it seeks. It contends that it could in any event not supply the services beyond 3 months because this would risk it losing a very lucrative contract for the supply of satellite services to a new customer.

6. For its part, EE would be prepared to pay Avanti a pro tem fee of £300,000 per month but it would need Avanti to maintain the services for longer than 3 months and ideally for 6-9 months. This is because while EE recognises that it cannot continue to take services from Avanti on a long-term basis at the rate required by Avanti and has indeed started to engage with a different satellite supplier to take over from Avanti, this process of “migration” is a protracted one if it is to be done properly.

7. Since the parties have been unable to agree a way forward after which they would effectively part company, EE has brought this application for an injunction, effectively to maintain Avanti services until the migration is complete or trial, whichever comes first.

8. As to the underlying merits of EE’s claim, Avanti disputes that it is presently under any continuing contractual obligation to supply the services. Strictly speaking, it says, it would be entitled to walk away now. In fact, and as noted above, it has never suggested that but instead and in order to facilitate an orderly migration, has intimated that the withdrawal of services would be on a phased basis. Avanti says that EE’s claim to be entitled to Avanti services for an effectively indefinite period is hopeless so that for present purposes, EE is unable to show that there is a serious issue to be tried. Of course, if that is right, the application for an injunction fails at the first hurdle.

9. If I were to find that there was a serious issue to be tried, EE then says that the balance of convenience, or as it is sometimes now put, the balance of least irremediable justice, lies in its favour. Avanti contends the opposite.

10. For the purpose of this application, I have two witness statements (“WSs”) from EE’s solicitor, Luke Pardey dated 24 March and 28 April 2025 (“LP1” and “LP2” respectively) and one WS from Avanti’s solicitor, Rhys Thomas, dated 17 April 2025 (“RT1”).

Nature of the services to be provided by Avanti

11. EE is a well-known mobile phone network provider and is one of the UK’s largest such providers. It is part of BT. For most parts of the country where EE’s mobile phone services are provided, the required link between its mobile phone mast sites and its core network infrastructure, is effected by fixed fibre/cable or microwave links. However, the remoteness of some areas or their terrain may mean that it is impracticable to use such links. In such cases, the link (or “backhaul”) is provided by satellite. Avanti provides such satellite links.

12. EE has around or makes use of about 20,000 mast sites. Of these, about 200 are in remote areas requiring satellite links as the primary connection with its core network. In other words, if the satellite link is not provided, then there will be no EE mobile services in the relevant area. There are a further 400 sites where the primary link is fixed fibre/cable or microwave, but if that primary link fails, a satellite link is required to act as the backup. The essence of the services provided by Avanti here consists of the provision of the initial infrastructure and then the provision of primary satellite links in the 200 sites and backup satellite links in the other 400 sites.

13. These services were provided, at least partially, in the context of EE’s separate contract with the Secretary of State for the Home Department (“the Home Office”) to provide mobile services including in respect of the Emergency Services Network which is a communications system commissioned by the government for use by emergency services, said to be a critical element of national infrastructure.

14. In the 600 sites referred to above, EE provides, through its own mobile network, the ability for any mobile phone user to make 999 calls even if this is in an area where that user’s own mobile network does not operate. In the 200 sites, if the satellite link fails or is no longer provided, it means that there is no ability for anyone using a mobile phone to access the emergency services. They can, of course, do so if they are able to use a landline in the ordinary way. For the other 400 sites, that contingency will arise if the primary backhaul link has failed, because there will be no backup satellite link.

The contractual framework

15. In around June 2016 EE and Avanti signed or entered into 3 separate contractual documents.

16. The first is described as a Supply of Goods and/or Services Agreement with a printed date on it of May 2016 (“the GSA”). The signatures are undated but for reasons which I shall explain, it is likely that they were made in around June 2016. There is no dispute between the parties that the GSA is a “framework agreement” in the sense that it contains a set of standard terms and conditions which the parties agree will form part of any particular contract for the supply of goods or services going forwards. However, it does not itself contain any obligations on the part of the supplier to provide particular goods or services for a particular price at a particular time. It is also an entirely generic document which purports to govern the provision of any kind of goods or services. It may not have been the most apposite contractual vehicle for the provision of the services at issue here, but this is what the parties signed.

17. The GSA contains a number of material terms, as set out below:

“1. Interpretation and Precedence…

1.3 In the event of any conflict between the GSA, the Engagement Form (if any) and any Order, the following decreasing order of precedence shall apply: a) the GSA; b) the relevant Order; and c) the Engagement Form (if any).

1.4 Where so advised by EE, the GSA shall incorporate and give precedence to (clause 1.2) the terms of Schedule B (Flow Down Terms). The terms of Error! Reference source not found. B shall only apply to the provision of Goods and Services by you to EE where you are so advised by EE, and in no other circumstances. The Supplier undertakes to accept all Engagement Forms and/or Orders where this clause 1.4 applies.

2. GSA and Ordering

2.1. If EE wishes to acquire any Goods and/or Services from you, it may enter into an Agreement by submitting Order(s). This GSA shall be incorporated into and shall apply to all Agreements unless expressly stated otherwise, or to the extent expressly stated otherwise, in an Agreement.

2.2. At EE's request, you shall cooperate in the preparation of an Engagement Form which shall contain as a minimum:

(a) the types and quantities of Goods and/or Services to be provided by you under the Engagement Form;

(b) the applicable Charges;

(c) the required address for delivery/implementation of such Goods and/or Services; and

(d) the required date of delivery of such Goods and/or Services.

2.3. Notwithstanding signature of this GSA or the execution of an Engagement Form between us, a binding contract for the sale and purchase of any Goods and/or Services shall only be formed once you accept the Order. EE shall have no liability to you (including, without limitation, any liability to make payment for Goods and/or Services already provided) for such Goods and/or Services until you have received a valid Order in respect of such Goods and/or Services from EE. Acceptance of an Order shall be upon your written confirmation of the Order, or the delivery of the Goods and/or Services to which the Order relates (whichever occurs first). For the avoidance of doubt, EE has no obligation to issue Orders hereunder.

2.4. This GSA shall operate to the exclusion of all previous versions of EE's standard terms and conditions (including any amendments to such terms and conditions) or any and all terms appearing on any quotation, acceptance form, delivery form, invoice or other document or letter issued by you…

3. Term and Exclusivity

3.1. Conditional upon you delivering a duly executed parent company deed of guarantee (in such form to be agreed between us) to EE, this GSA shall commence on the date set out above and shall remain in force unless terminated in accordance with its terms.

3.2. The Goods and/or Services shall be provided on a non-exclusive basis and EE shall be free to procure any services and/or goods identical or similar to the Goods and/or Services in-house or from any other supplier at any time during the Term…

14. Termination and Consequences

14.1. Either Party may terminate this GSA or any Agreement immediately on written notice without prejudice to that Party's other rights and remedies under the GSA or such

Agreement if the other Party:

(a) is in material or persistent breach of the GSA or the relevant Agreement and either such breach is not capable of remedy or such breach remains unremedied for thirty (30) days from the date the defaulting Party is notified of such breach by the non-defaulting Party; or

(b) suffers an Insolvency Event or any similar event in any jurisdiction.

14.2. EE may terminate this GSA or any Agreement immediately at any time by giving you notice in writing. In the event of termination in accordance with this Clause, EE shall be liable to pay you the Charges on a pro-rata basis so that EE is only obliged to pay you: (1) for the Goods and/or Services actually delivered or provided to EE in accordance with the Agreement at the date of termination and (2) for any committed irrecoverable costs which are not included in the pro-rata Charges calculated in accordance with part (1) of this clause 14.2 and which the Supplier can provide evidence to EE that it is obliged to pay as a direct result of complying with EE's instructions under this GSA or any Agreement.

14.3. EE may terminate this GSA or any Agreement immediately if you are subject to a change of control (as defined by sections 450 and 451 of the Corporation Tax Act 2010). You shall notify EE as soon as practicable after any change of control takes place.

14.4. Termination of the GSA alone shall not of itself terminate or otherwise affect any Agreement. Termination of any Agreement shall not of itself terminate or otherwise affect the GSA or any other Agreement. Termination or expiry of an Agreement shall not affect any rights, remedies, obligations or liabilities of the Parties that have accrued up to the date of termination or expiry…”

18. Schedule A to the GSA contains the following definitions among others:

"Agreement" means an Order (a) pursuant to and incorporating the terms and conditions of the GSA; and (b) pursuant to and incorporating the relevant Engagement Form (if any) to which the Order relates;

"Charges" means any fee or price owing by or to either Party as agreed and set out in the relevant Agreement and which may be based on a Rate Card;

"Engagement Form" means an engagement form, statement of work or other similar document, detailing the Goods and/or Services to be provided by you to EE and created pursuant to Clause 2.2, the proforma document for which is set out in Schedule D;

"Order" means an official written EE purchase order placed by EE's Procurement Department pursuant to the terms and conditions of the GSA, including any scheduling agreement issued to you by EE;

“Term" shall mean the term of this GSA as set out in Clause 3.

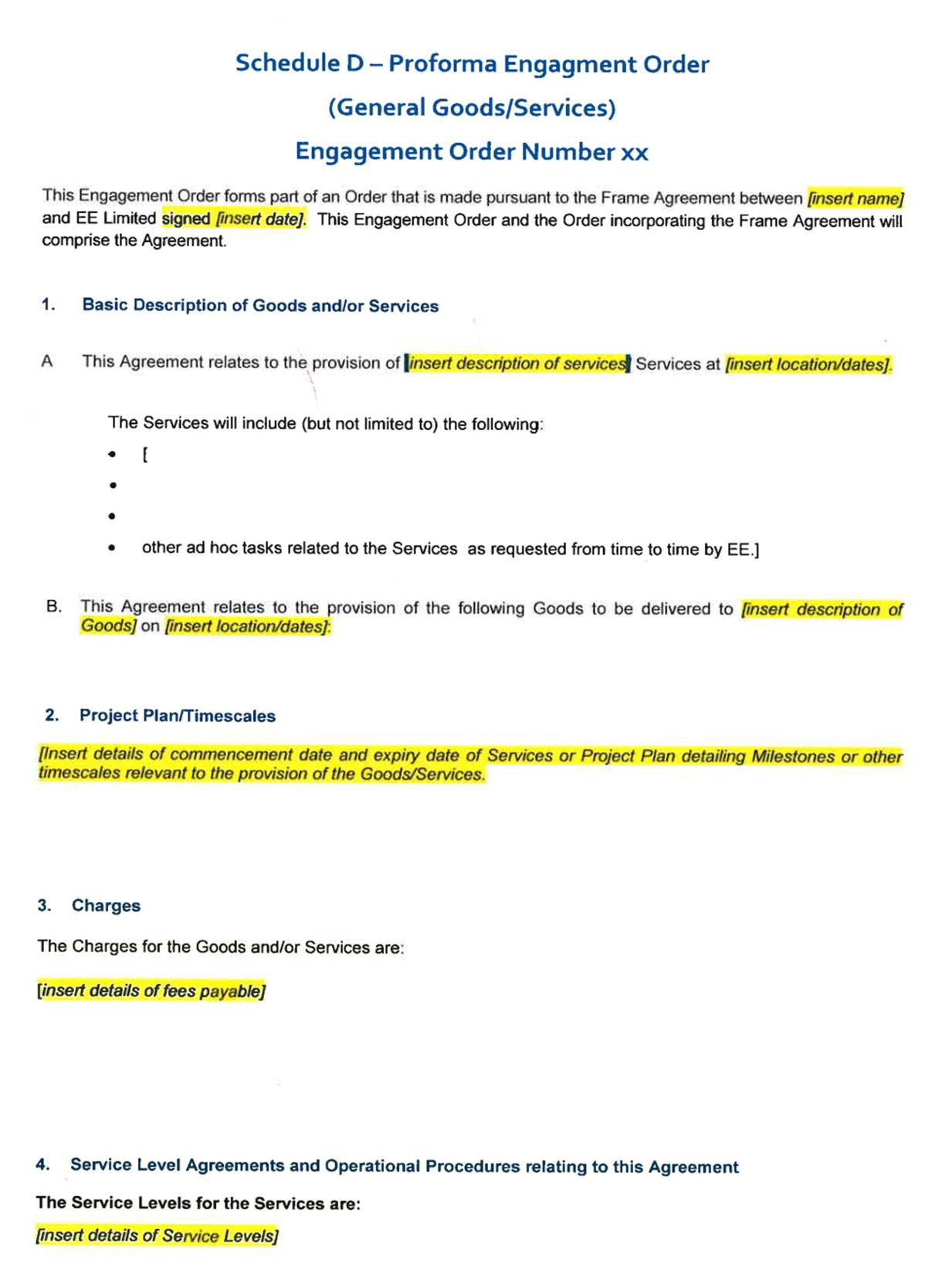

19. The proforma set out in Schedule D to the GSA reads thus:

20. Pausing there, the contractual structure contemplated by the GSA, pursuant to which the goods or services were to be supplied by Avanti to EE, appears to be as follows:

(1) EE would submit to Avanti an Order (as defined), which itself would contain the terms and conditions within the GSA; see Clause 2.1;

(2) If Avanti accepted the Order, either by confirming it in writing or delivering the services to which the Order related, there would then arise a binding contract between the parties for the supply of those services; see Clause 2.3;

(3) If EE requested it, then Avanti would cooperate with EE to prepare an Engagement Form which would set out the relevant services to be provided, the price of those services and details as to delivery; see Clause 2.2;

(4) The terms of any Engagement Form would themselves form part of any Order which was accepted by Avanti and the resulting Agreement; see Schedule D and also the definitions of Agreement and Engagement Form;

(5) It would be possible for there to be an Order without an Engagement Form because the preparation thereof was at the behest of EE; again, see Clause 2.2., Of course, the Order would have to detail the services to be provided and their price, but this would not be necessary if there was an Engagement Form which specified them.

21. Taken at face value, the first sentence of Clause 2.3 is extremely clear: there is no binding contract (and therefore contractual obligation) to supply goods or services until and unless there is an Order which has been accepted by Avanti in the modes later described. Moreover, it is expressly stated that this is the position regardless of the signature of the GSA or the execution of an Engagement Form. As I shall explain below, EE’s primary position is that it is not in fact the case that accepted Orders are a pre-requisite to contractual obligations upon Avanti to supply. Avanti’s position is to the contrary.

22. In this case, the parties did indeed agree an Engagement Form. Further, at all times Orders were issued by EE and accepted by Avanti in respect of the services they provided. This is set out in detail below.

23. EE at the hearing took a further point which it said supported its case, arising from Clause 1.4 cited above. I shall deal in context with that below.

24. As for the termination provisions set out in Clause 14, which deal simply with the GSA, it can be seen that while EE has the right to terminate the GSA “without cause” as it were, Avanti can only terminate it “for cause”. It is common ground that the GSA has not been terminated and, to the extent relevant, continues in existence.

the facts

The Statement of Work

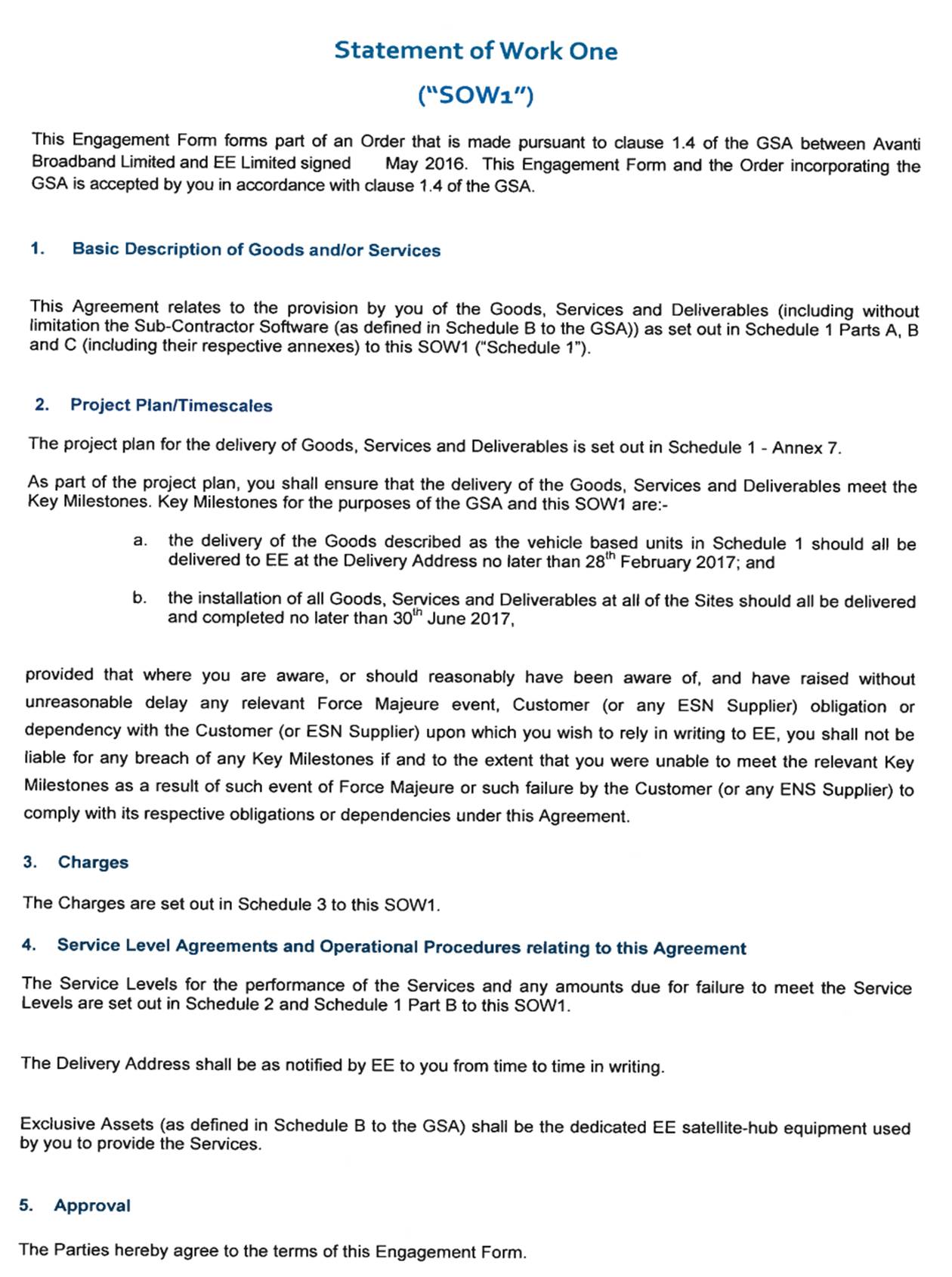

26. It is a very substantial document because it sets out in great detail the precise services to be supplied by Avanti. For present purposes, the material parts are set out below.

27. The first and second pages read as follows:

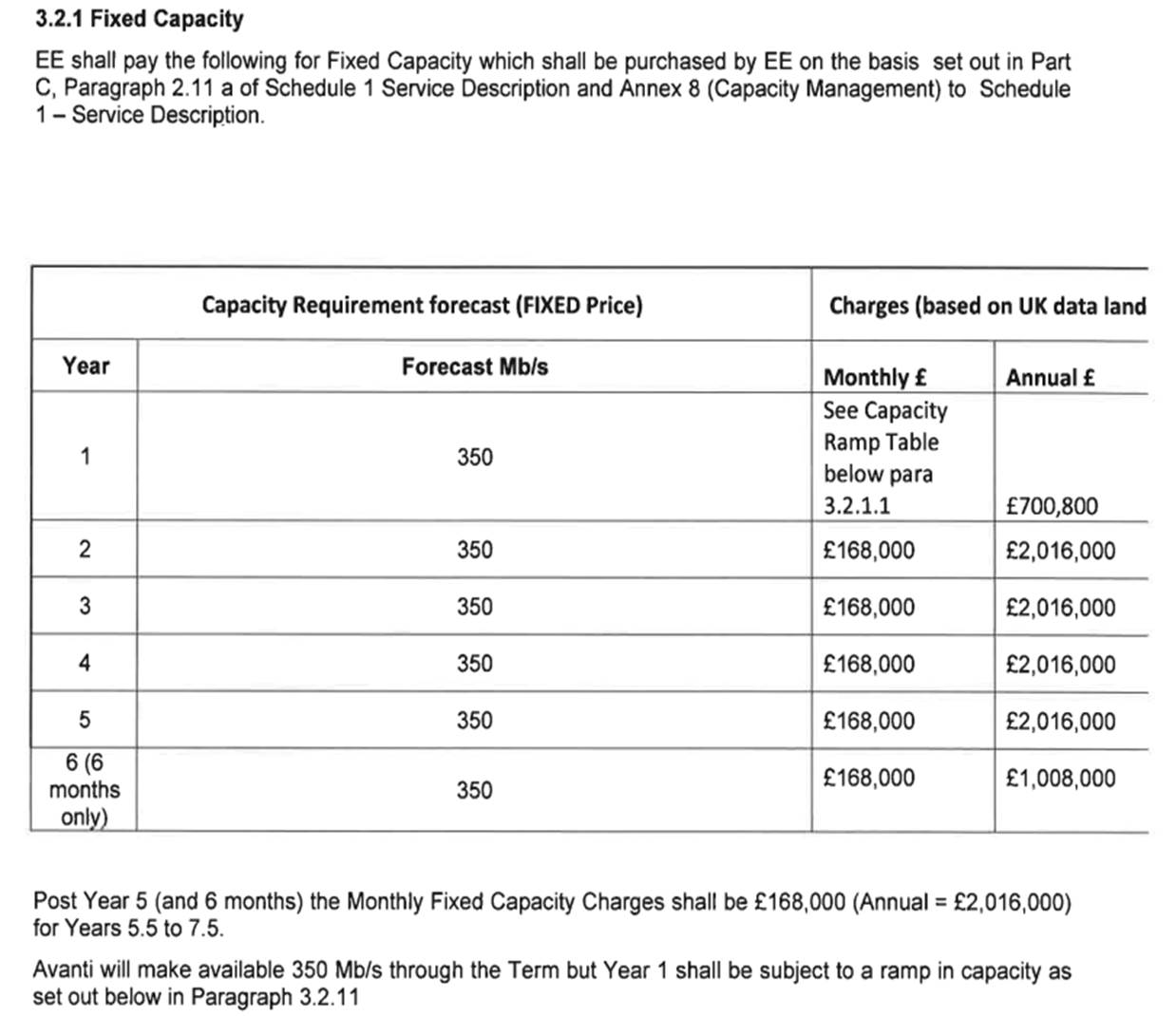

28. Schedule 3 to the SOW deals with the charges for the services provided. It is common ground that there were one-off charges to be paid in connection with the set-up of the infrastructure. These are set out at paragraph 3.1.

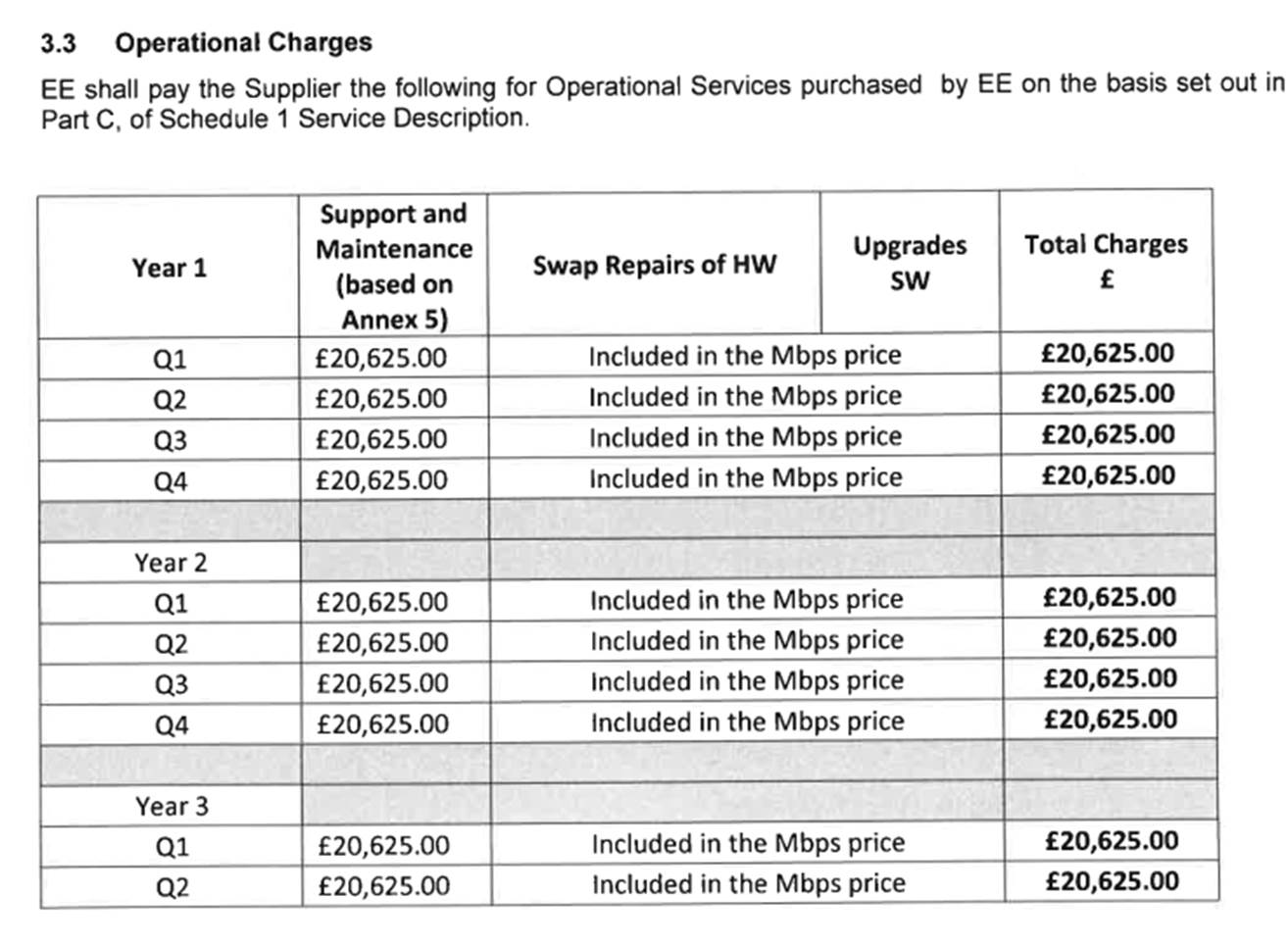

30. Another regular charge was set out at paragraph 3.3, being “Operational Charges”, as follows:

31. What both of these provisions show is that the parties had agreed prices in respect of fixed capacity and operational charges for the first 7.5 years of the provision of the services. This period would therefore end in December 2023, assuming that the services were first provided in July 2016.

32. I deal below with the nature and effect of the SOW. However, in summary, the parties’ positions are these: Avanti says that this is in effect a further framework contract which, for the first 7.5 years of the supply of any services by Avanti, provides the content of any PO made. However the SOW itself does not create any binding obligation to supply such services.

34. I will refer to some further terms of the SOW when analysing the parties’ positions below.

The Purchase Orders (“POs”)

35. A total of 21 POs were issued, the last being dated 5 February 2025. Their individual dates and numbers are set out in a table produced by Avanti which is not in dispute.

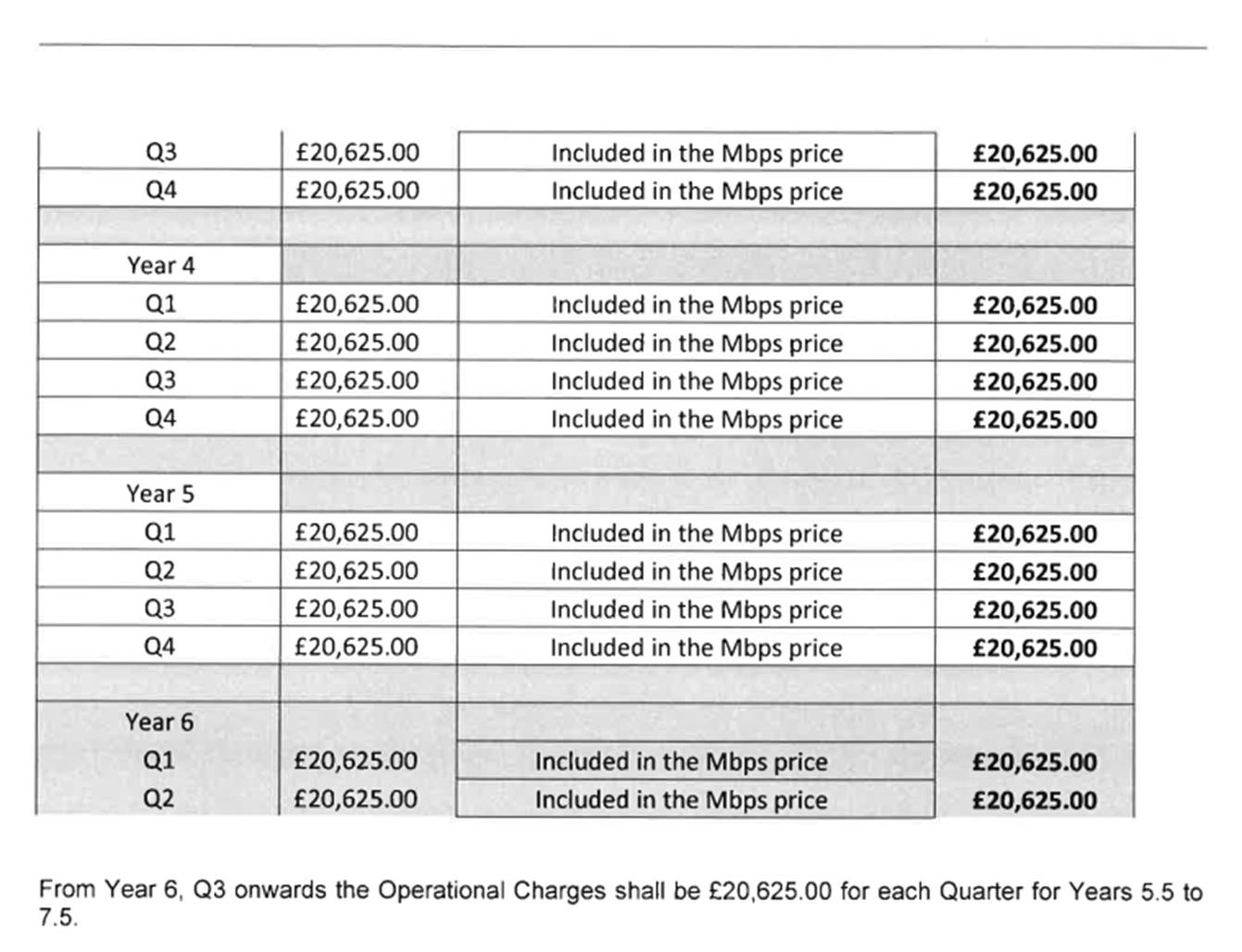

36. The first PO is dated 23 June 2016 (“PO1”). It reads as follows:

38. It is common ground between the parties that although not stated in PO1, the services to be provided were as set out in the SOW.

39. All of this accords with the contractual scheme contemplated by the GSA.

40. Two other POs have been exhibited by Avanti as examples.

41. One is a PO dated 1 March 2022, which is in fact the third in time. It is expressed to cover the provision of services from 9 December 2021 to 28 February 2022 and is for the fixed capacity charges at £168,000 per month.

42. The other is a PO dated 9 November 2023 which is for fixed capacity services provided from 1 October to 31 December 2023. It will be noted that this is the last period for which actual prices were provided by the SOW.

Changes to the SOW

“CHANGE NO. 1 - IN-LIFE CAPACITY MANAGEMENT, TRANSFER OF SERVICES FROM HYLAS 1 TO HYLAS 4:

(a) To provide EE with expansion path for additional capacity and specifically addressing the increasing demand for return path capacity based on increasing symmetry in forward and return directions.

(b) Increases lifetime of space segment from 7 years (HYLAS 1) to 19 years (HYLAS 4).

(c) To complete the transfer before the end of 2018 to accommodate new ESN services/users starting from January 2019.

CHANGE NO.2 - COMMERCIAL IMPROVEMENTS

(a} a revised price of £400 per Mbps on a pay-as-you-go basis for any burstable additional capacity outside of the Fixed Capacity has been agreed.

The Parties have also agreed that Supplier will use reasonable efforts to make service improvements as identified in part 'a' below of this CCN00S. This will not be a formal change to the Agreement…

This CCN shall expire only on termination of SOW 1”

44. HYLAS 1 and HYLAS 4 are satellites operated by Avanti. At this time, Avanti was also using its HYLAS 2 satellite to provide its services.

The Parties’ Negotiations

45. It is common ground that from around May 2023 the parties started negotiating for new pricing for the period beyond 31 December 2023. On 9 June 2023, Avanti produced detailed new pricing proposals for either a 3 or 5 year commitment. Further proposals were sent by Avanti on 4 July, 8 August, 8 and 29 September, 23 October and 2 November 2023. In fact Avanti offered to reduce prices for EE but this depended on migrating the services then provided through HYLAS 2 to HYLAS 4, so that HYLAS 4 was the only satellite being used. However, as at the end of 2023, no agreement had been reached. In particular, EE opposed the migration from HYLAS 2 to HYLAS 4. See, for example, the email from Mr Chopra of EE dated 11 December 2023.

46. On 29 December 2023 Mr Vines of Avanti emailed Mr Chopra as follows:

“As you know, the current GSA expires on 31st December. Therefore we have prepared for your review and signature the attached CCN008, which enables the existing contract to be extended on a rolling month-by-month basis whilst the parties negotiate and agree CCN007. I trust this is acceptable and would be grateful if you could please share your signed version once done. Please don’t hesitate to contact me in case of any questions.”

47. CCN7 was proposed to create a “renewed term of the GSA for a further 5 years”.

48. On around 23 January 2024, Mr Chopra sent a revised draft CCN8 to Mr Vines. However, this was not ultimately agreed.

49. As from 1 January 2024, Avanti kept on providing the services to EE pursuant to POs at the original rate but with Avanti reserving its position. In particular, Mr Vines emailed Mr Chopra as follows on 9 May 2024:

“…Please find attached an invoice for equipment ordered in November under PO PO4501449063, as well as monthly invoices for January, February, March and April. These monthly invoices relate to services Avanti continues to provide pending renewal of the General Supply of Goods and/or Services Agreement, agreed between the Parties dated May 2016 (“GSA”). We acknowledge that the parties have had differing views on the expiration date of the GSA but Avanti has continued to provide services on a monthly basis as a token of commercial good faith. Both the submission and payment of these invoices is without prejudice to the position each party has taken. We will continue to provide these interim services on a rolling monthly basis whilst the parties continue to discuss the terms for the renewal, but we can only do so on the basis of payment of those services.

We will continue to provide services in good faith, and we continue to work on the 5-year contract renewal, as we are very motivated to extend our partnership for many more years to come. We will continue to work on the migration, and this will maintain our full focus, however it is imperative that we resolve the cash position as a matter of urgency.

It would be appreciated if you could confirm the payment of the Q1 services by 10 May 2024 to confirm that the payments will be made on 15 May 2024, as we will need this information to support our cash forecasting.

Whilst the POs attached do correctly reflect the charges, our invoice against these services will be issued expressly on the basis of a reservation of the parties position regarding the status of the GSA (with Avanti maintaining that it has terminated and that these services are being provided on a good will basis outside the term). We specifically reject the applicability of EE General Conditions. We will proceed to issue invoices on this understanding…”

50. On 30 May 2024, Avanti sent to EE headline terms for CCN7 which included some changes to the GSA. This was rejected by EE on 11 June. There were further negotiations and drafts between July and December 2024 but without an agreement.

51. In the meantime, Avanti had received several offers to supply its satellite services to others. In particular, on 21 November 2024, it signed a letter of intent for a new long term contract worth up to $147.5 million (“the LOI”). A copy of the LOI has been provided to EE in a redacted format on a confidential basis. I was not provided with a copy and was not asked to look at it. So I have not seen it. However at paragraph 36 of RT1 he says this about it:

“36.1 The letter of intent provides for a seven-year contract, with the final two years being optional.

36.2 The price of the services over the five-year period amounts to USD 112.5 million, and for the seven years USD 147.5 million.

36.3 The letter of intent contains an exclusivity period up to 31 January 2025, which was amended by a letter dated 17 February 2025 to 28 February 2025 and further amended by a letter dated 7 March 2025 to 31 March 2025. Avanti and the third party are currently engaging in discussions around a further extension of the exclusivity period.

36.4 Avanti is continuing to negotiate the detailed terms of the New Contract with the customer. However, I am instructed by Bridget Sheldon-Hill, Avanti's General Counsel ("Ms Sheldon-Hill"), that there is urgency to concluding the New Contract - and that, if the dispute with EE is protracted, there is a real and significant risk that the opportunity will be lost.”

52. Initially on 17 December 2024 and then formally on 10 January 2025, Avanti proposed a new 7 year agreement with a much increased monthly price of £812,500. According to paragraph 40 of RT1, the background to the making of this offer was not merely the LOI, where there was a time-factor, but the fact that this was the sort of charge which Avanti could make to others for the supply of these services.

53. On 30 January 2025, EE responded as follows:

“Thank you for your letter dated 17th January 2025, in which Avanti seeks to increase service charges to £812,500 per month (approximately four times the current charges) and to change the terms of the Agreement, effective 1 February 2025.

Having undertaken a detailed review of your correspondence, the General Services Agreement (GSA), and the associated Change Control Notices (CCNs), we find no legal or contractual basis for this proposed increase or the changes to the terms of the Agreement. Accordingly, we dispute and reject both the price increase (as well as any associated invoices that include the revised charges) and the changes to the terms.

The GSA explicitly requires that any changes to charges be agreed through the formal Change Control process. No such agreement exists in relation to your proposed increase. While we acknowledge that CCN005 has expired, this does not grant Avanti the right to impose new pricing unilaterally. In the absence of a validly executed replacement CCN or other mutual agreement, the pricing set under the existing GSA remains binding.

We note that your letter suggests invoices may be issued without a Purchase Order (PO) or Authorisation to Invoice (ATI). However, this position is inconsistent with the GSA, which ties the validity of invoices to compliance with agreed procedural requirements.

We understand that Avanti may wish to discuss adjustments to the current arrangement, and we are willing to engage in constructive discussions about the future of the services. That said, Avanti remains obligated to continue providing services at the current agreed rates under the GSA unless and until a properly executed CCN or amendment is in place.

We are confident this matter can be resolved amicably without the need to invoke formal dispute resolution mechanisms. Please feel free to contact me directly at your earliest convenience to discuss this matter further.”

54. That prompted the following response from Avanti on 31 January 2025:

“As you acknowledge, the Updated Statement of Work for the services (CCN005) has expired, and there is therefore no contractual or commercial coverage for the services which we have been providing, on a monthly rolling basis, on a good will basis. I do not understand EE’s suggestion that the expired commercial terms of CCN005 continue to apply to these services in perpetuity until some different agreement is negotiated - that would not make commercial sense and is directly inconsistent with the express terms of Clause 2.3 of the GSA.

CCN005 provided the proposed Charges for the services for a fixed 7.5-year period ending on 31 December 2023. Continuation of services beyond this period requires the parties to agree new commercial terms. Although we have continued to provide services on a good will basis, there is no contractual obligation for us to do so, and certainly not on the financial terms agreed in 2018.

As we discussed, the updated charges we have proposed are not arbitrary, but rather reflect the commercial terms that a third party has indicated to us that they would be willing to commit to through a long-term contract. In those circumstances, it is difficult to see how EE could reasonably expect us to continue to provide services at a substantially lower price, nor indeed how our directors could, in the discharge of their fiduciary obligations to the company and its shareholders, accept anything else.

We will therefore be issuing an invoice for £812,500 in respect of February services. If this is not paid within 30 days, we cannot continue to provide services on the same basis. In the event of non-payment, we will have no option than to start taking steps to redeploy the capacity to third parties on market commercial terms at the beginning of Q2 2025. It goes without saying that we would prefer to reach a long-term commercial agreement to continue to support EE on this project. However, we cannot continue to provide services at a substantial loss.”

55. In the meantime, on 28 January 2025, EE issued a Request for Proposal (“RFP”) to identify a replacement supplier for Avanti on the closest like for like solution. According to LP2, an alternative supplier has been found, offering a 3 year contract at £3.5m per annum which is some £6.25m less than Avanti’s offer.

56. On 4 February 2025, Avanti issued an invoice to EE for £812,500 which EE then disputed. There were further attempts to find a way forward which did not succeed, and on 7 March, Avanti wrote to say that it now reserved the right to suspend services for non-payment. Payment was not received and on 14 March 2025, Avanti wrote to say that it would commence a phased withdrawal of its services on 24 March over a period of 6 weeks.

57. On 21 March, EE’s solicitors (CMS) wrote to say that an application for an injunction would be made unless the threat to suspend services was withdrawn.

58. On 24 March 2025, CMS wrote to Jones Day, Avanti’s solicitors, to say that it would pay the February 2025 invoice in full if Avanti agreed not to suspend any services until 14 April. On the same day, this application for an injunction was made. Avanti agreed not to suspend services until 14 April but EE would have to pay the March 2025 invoice on the same basis as well.

59. The upshot was that EE then did pay the February 2025 invoice in the full amount under protest. The parties also agreed that pending the outcome of the hearing before me, Avanti would continue to provide the services, with EE paying 50% of the March 2025 invoice, and there the position rests.

The Present Position

60. What is plain from the chronology set out above is that irrespective of the true contractual position, both sides will in fact part company. Although the injunction sought is until trial or further order, the reality is that EE wants Avanti to keep providing the services until such time as the replacement supplier for EE is operational. For its part, Avanti does not wish to lose the opportunity afforded by the LOI in the meantime.

61. At the conclusion of the hearing, and given that the central issue for any trial would be the correct contractual position in respect of Avanti’s obligation or otherwise to keep on providing its services to EE, which is a matter of construction, I invited the parties to agree to an expedited trial lasting 2 or 3 days. I could offer such a trial in the week commencing 7 July 2025 if there were appropriate undertakings from Avanti in the meantime. Avanti was prepared to agree to this, but EE was not, because it considered it would need more than 2 months to prepare for such a trial and also because its present Leading Counsel would not be available. Given that disagreement, this present judgment is given.

the law

62. Unsurprisingly, there is no dispute between the parties as to the general applicability and content of the American Cyanamid principles.

63. However, Avanti contends that although phrased in negative terms, the injunction sought here is in reality a mandatory injunction to compel it to keep on performing its services for EE until trial or further order. That being so, and in relation to the merits threshold to be satisfied on an application for an interlocutory injunction, the appropriate test is not the usual “serious issue to be tried” but rather the higher standard of the applicant being able to show with a “high degree of assurance” that it is likely to be held entitled to the injunction at trial.

64. In this context, Avanti relies upon dicta from cases such as Films Rover International Ltd v. Cannon Film Sales Ltd [1987] 1 WLR 670, at 680-681, Harmony Innovation Shipping PTE Ltd v. Caravel Shipping Inc [2019] EWHC 1037 (Comm) and Harvey v Santander UK Plc [2023] EWHC 2947.

65. For its part, EE responds that in this case, there is no basis for a higher merits threshold. It relies in particular on the opinion of Lord Hoffmann in the Privy Council decision in National Commercial Bank Jamaica Ltd v Olint Corpn Ltd [2009] UKPC 16 at paragraphs 18-21. At paragraph 20 he disavowed the “box-ticking” exercise undertaken by the courts below whereby if the injunction was prohibitory the test was “serious issue to be tried”, whereas if it was mandatory the test was a “high degree of assurance”. The position was more nuanced than that, as the following passage from paragraph 19 made clear:

“What is true is that the features which ordinarily justify describing an injunction as mandatory are often more likely to cause irremediable prejudice than in cases in which a defendant is merely prevented from taking or continuing with some course of action: see Films Rover International Ltd v Cannon Film Sales Ltd [1987] 1 WLR 670, 680. But this is no more than a generalisation. What is required in each case is to examine what on the particular facts of the case the consequences of granting or withholding of the injunction is likely to be. If it appears that the injunction is likely to cause irremediable prejudice to the defendant, a court may be reluctant to grant it unless satisfied that the chances that it will turn out to have been wrongly granted are low; that is to say, that the court will feel, as Megarry J said in Shepherd Homes Ltd v Sandham [1971] Ch 340, 351, a high degree of assurance that at the trial it will appear that the injunction was rightly granted.”

66. EE also points out that here, while Avanti would be compelled to continue to provide its services to EE, it would not be unduly burdensome or difficult for it to do so in and of itself, as it has been doing so since 2016. This is a far cry from a mandatory injunction requiring a property owner, for example, to demolish or indeed erect a substantial structure, or provide services to a party or do acts which would then be likely to require policing.

67. In my judgement, in this case, it would be undesirable for the court to choose between the two merits threshold tests where the essence of the issue is a point of construction and a relatively short one at that, in my view.

68. Accordingly, I shall apply the usual “serious issue to be tried” test. I should add that this is not the sort of case where the underlying merits turn or turn significantly on disputed questions of fact where it might be relatively easy to surmount this threshold or where, indeed, the defendant is prepared to accept that the threshold is met and concentrates rather on the balance of convenience. Here, as already noted, the issue is one of contractual construction where Avanti contends that EE’s claimed construction is plainly wrong and cannot therefore give rise even to a serious issue to be tried.

69. I now turn to that matter.

serious issue to be tried

Introduction

70. As already indicated, the resolution of the contractual dispute between the parties involves a relatively short point of construction.

71. EE’s primary position is that by reason of the SOW, Avanti was and remains contractually obliged to provide its services on an indefinite basis and until or unless either party is able to, and does terminate the GSA. For the period after 31 December 2023, and because no price was agreed, Avanti is bound to provide those services for a reasonable charge by reason of s15 of the Supply of Goods and Services Act 1982 or other implied term. If the parties could not agree what such a charge was, ultimately the Court would have to decide the matter. Previously, of course, EE had contended in correspondence that Avanti was in fact bound to pay the original agreed price on an ongoing basis, absent any agreement.

72. Avanti’s position is that there is no indefinite contractual obligation and in the absence of an accepted PO, there is no obligation to provide further services. Thus it says that it is presently free to withdraw its services although thus far, it has only threatened to do so on a phased basis.

73. As to that, EE has two fallback positions:

(1) If it is necessary to have a PO, then it relies on PO, which is says is sufficient to trigger the operation of the SOW but again, on an indefinite basis;

(2) It can rely on Clause 1.4 of the GSA which provides for an indefinite obligation even if the SOW itself otherwise does not.

74. I intend to address the parties’ primary positions first.

Clause 2 of the GSA

75. This is set out in paragraph 17 above. Both sides accept that the GSA is plainly a framework agreement, and does not stipulate any indefinite supply obligation on the part of Avanti. But it goes further than this because of the contractual structure it creates by Clause 2.

76. Clause 2.3 is worth repeating:

“ Notwithstanding signature of this GSA or the execution of an Engagement Form between us, a binding contract for the sale and purchase of any Goods and/or Services shall only be formed once you accept the Order. EE shall have no liability to you (including, without limitation, any liability to make payment for Goods and/or Services already provided) for such Goods and/or Services until you have received a valid Order in respect of such Goods and/or Services from EE. Acceptance of an Order shall be upon your written confirmation of the Order, or the delivery of the Goods and/or Services to which the Order relates (whichever occurs first)…”

[underlining added for emphasis]

77. On the face of it, then, an accepted PO is necessary to found any obligation on the part of Avanti to supply the services. In argument, EE sought to diminish its importance on the basis that it was merely an aspect of contract administration or good contract governance, which was not a pre-requisite to contractual obligations. In my judgment this is plainly not so. The words could not be clearer as to their meaning. The argument made by EE here is redolent of the argument made as to what PO1 showed which I rejected at paragraph 37 above. (For the sake of completeness, I should add that I do not consider that EE’s argument here was assisted by paragraph 4.1.1 of Schedule 3 to the SOW which dealt with invoicing, stating that invoices from Avanti would not be paid absent the services being ordered by Engagement Form or Order or other express confirmation from EE. I do not see paragraph 4.1.1 as mere “nuts and bolts” thereby adding to the view of Clause 2.3 as being no more than contract administration.)

78. In any event, EE effectively recognised in argument, that it would have to look elsewhere for an indefinite obligation to supply because that was not contained in the GSA. That brings us to the SOW.

The SOW

Introduction

79. This is set out at paragraphs 25 - 33 above. The first point to make is that this is not, nor does it purport to be, some contractual document different from what might be expected, or an express variation to the GSA. It is an Engagement Form, as contemplated by Clause 2.2 of the GSA and following the broad form of that set out in Schedule D to the GSA (shown at paragraph 19 above).

80. The introductory part of the SOW itself is shown at paragraph 27 above. It refers back to the GSA and itself forming part of an Order, which is consistent with the need for an Order.

81. It is plain, in my view, that there is nothing in the SOW which sets out an express obligation on the part of Avanti to supply its services.

82. It is, however, true that on any view, it has set out the basis on which any services which were provided, would be so provided for the next 7.5 years. This is because of Clause 3.2.1 of Schedule 3, set out at paragraph 29 above. Here, however, EE submitted that it was implicit in this provision that there was such an indefinite obligation, and that this can be seen from various parts of the SOW. It so submits for a variety of reasons to which I now turn.

The “Mandatory” Point

83. First, Mr Lavy KC argued there were mandatory terms employed. For example, paragraph 1 of Schedule 1 refers to the services “to be provided” while Section 5 thereof refers to the Goods “shall be delivered”. Also in Schedule 1 Service Description, paragraph 2 says that “The Supplier shall have full responsibility for the 'end to end' deployment and delivery of the Solution for the list of Sites provided by EE.”

84. Then as part of the Operational Services section, paragraph 2.14.4 states that “The Supplier is responsible for all Goods or hardware upgrades required at the Sites”. Yet further, paragraph 1.1.1 under Annex 8 Capacity Management Process says that “Fixed Capacity of 350Mbps will be provided across the 3 Beams in Figure 2 (above) and charged as per Schedule 3 (Charges).”

85. I see all of that that, but I do not accept that use of such mandatory language indicates the creation of an indefinite obligation to supply. Rather these passages indicate what type or level of service is to be provided when Avanti does supply its services and in this case, very considerable detail, much in the way of a specification, is needed. But none of that negates the need for a PO.

The “Agreement” Point

86. Next Mr Lavy KC points to the use of the word “Agreement” in, for example, Schedule 1 which refers to “During this Agreement” in (again) paragraph 1 of Schedule 1, and Annex 8 Capacity Management Process, paragraph 1.1 of which makes a reference to “Service Capacity available under the Agreement is defined within Figure 1 and Figure 2 below.” Also paragraph 2.1 of Schedule 3, dealing with charges, states that “EE shall pay the Supplier, in accordance with the agreed timeframes as set out in this Schedule 3, for the provision of the Goods and/or Services to EE by the Supplier under this Agreement.”

87. What is said is that this indicates that the SOW is a free-standing agreement, itself obliging Avanti, without more, to provide the services.

88. “Agreement” is not a defined term under the SOW; however, it is a defined term under the GSA and it refers to an Order, which takes us back to a PO and the SOW being a part of it, which is exactly how the SOW starts. So I do not think that this shows that the SOW is itself a complete contract imposing in itself an indefinite obligation to supply. Indeed, of course, at around the time of the making of the GSA and the SOW, PO1 was issued (and accepted).

The Term and Duration Point

89. Thirdly, EE places considerable reliance of the use of the word “Term” in the SOW. This occurs in various places. So, for example, under Annex 8 Capacity Management Process, paragraph 1.1 states that “The Service Capacity as described in Fig 1 and Fig 2 below shall be made exclusively available to EE by the Supplier at all times during the Term” and “Avanti agrees not to relocate HYLAS 1 at its current orbital position of 33.SW or HYLAS 2 at its current orbital position of 31E during the Term.”

90. Then, as part of Schedule 1 Service Description, under Section 4 Spare Parts Management:

“EE may change the Goods support option that it receives by giving the Supplier no less than three (3) months' notice in writing, EE shall not change the option that it receives more than once in any year of the Term and may only change such option after it has received at least one (1) year of Goods support).”

91. One then goes to Schedule 3 dealing with charges, where, under the table, it is stated “…Avanti will make available 350 Mb/s through the Term but Year 1 shall be subject to a ramp in capacity as set out below in Paragraph 3.2.11.”

92. EE submits that as the word “Term” is used with a capital “T” but is not defined in the SOW, it must be defined according to the GSA. It is specifically defined there under Clause 3 (cited at paragraph 17 above) to mean the term of the GSA until the GSA terminated according to its terms. Since it is common ground that the GSA has not been terminated, it follows that the “Term” of the SOW must be the same as the Term of the GSA. It follows that the SOW remained operative for a period beyond the first 7.5 years referred to in Schedule 3, even though no prices were agreed for such a following period. If that is so, it suggests that the SOW is a self-contained contract which includes an indefinite obligation to supply.

93. Before analysing that argument, I need to refer to a related point which is really made in the same context. This concerns some of the specific wording of Schedule 3 to the SOW.

94. Mr Lavy KC submits that significance must be attached to the words that follow the table in paragraph 3.2.1. This is because the table itself only deals with 5.5 years. The charges for years 5.5 to 7.5, albeit in the same amounts, only come in the text following the table:

“…Post Year 5 (and 6 months) the Monthly Fixed Capacity Charges shall be £168,000 (Annual= £2,016,000) for Years 5.5 to 7.5….”

95. He submits that this must mean that this provision was indeed stating an obligation to provide, going beyond Year 7.5, because otherwise why not have Years 5.5 to 7.5 simply catered for in the table?

96. He makes the same point in relation to paragraph 3.3 which deals with Operational Charges. The table there sets the prices for the period up to Year 6.5 and then says below the table:

“From Year 6, Q3 onwards the Operational Charges shall be £20,625.00 for each Quarter for Years 5.5 to 7.5.”

97. Accordingly, it is submitted, these passages show that it was intended that the SOW should apply beyond 7.5 years, in which case it suggests an indefinite obligation to supply, even if this was to be on the basis of a reasonable charge.

98. In relation to this point about the wording of these passages, I think that EE’s argument here reads far too much into the words used. I agree that the table could have included all the charges for the following years, but as a scheme of agreed payments, the words used make complete sense without having to give them the interpretation suggested by EE. The underlying reality was that on its face (and subject to the use of the word “Term”), the SOW simply does not provide for a situation after the first 7.5 years.

99. Accordingly, I do not consider that this point adds weight to or otherwise supports EE’s argument about the use of the word Term or the SOW’s duration and effect generally. I now turn to the use of the word “Term”.

100. The first thing to note is that there are, strictly, two separate but related questions: (a) what is the duration of the SOW and (b) whatever its duration, did it create an indefinite obligation to supply beyond the last PO? I consider each in turn.

101. I see the force of the point that the word “Term” in places other than Schedule 3 should be defined by reference to what is said in the GSA and therefore it runs alongside the GSA itself, as it were. However, in my judgement, there are a number of significant counter-arguments which I set out below.

102. First, the logic of any reference to a term in the SOW is surely to the duration of the standing terms which would then form part of any PO or - on EE’s case - in any event, but that points strongly to 7.5 years for these reasons; EE now accepts that if the SOW were to last longer than 7.5 years, the only charge claimable by Avanti would be a “reasonable charge”. But as a matter of commercial reality, I regard that as absurd and unworkable where, on EE’s case, the duration of the SOW is effectively indefinite subject only to termination of the GSA. The range of services is extensively and highly prescribed and the notion that either party would bind themselves simply to pay or be paid a “reasonable price” in relation to services of this kind I consider to be fanciful.

103. Indeed, EE did not suggest the applicability of a “reasonable charge” until these proceedings were issued. Rather, (although this was obviously wrong) it had previously suggested that unless terminated Avanti would be bound to continue to supply on the basis of the existing charges.

104. Next, one only has to ask the rhetorical question as to the intervals at which any “reasonable charge” would have to be agreed to see that a system of pricing like this would be unworkable unless the parties were prepared to have frequent recourse to the Court to determine the question.

105. EE submits that this is an exaggerated concern, however, because after all, some sort of pre-termination charges were put in place for February and March 2025 although no longer. That is true but they were agreed without prejudice to the parties’ right to argue what the charge should be hereafter. Indeed EE suggested that going forwards, pending a trial, an appropriate amount would be £300,000 per month rather than the previous £168,000 per month but this was rejected by Avanti. In the absence of an agreement and if I were to grant the injunction, it would be left to me to decide what amount to stipulate pro tem. However, none of that means that the concept of charging on a “reasonable basis” long-term would make any commercial sense here. I do not accept that agreeing such reasonable charges would be as straightforward as EE suggests, for example by resort to competitors’ prices.

106. Further and if one was looking at the SOW alone, it seems to me that the common-sense interpretation of “Term” would be the duration of the pricing agreed, because this is where one found a defined period.

107. In relation to Schedule 3, Mr Parker KC made the further point that in terms of definition, paragraph 1.2 stated that

“Defined terms used in this Schedule 3 shall have the same meanings given to them in Schedule A and/or Schedule B to the GSA, unless stated otherwise.”

108. Accordingly, he said, this would be an example of where it was “stated otherwise”, not expressly but by reference to the very fact of the period set out in Schedule 3. Of course, even if this were correct, it would not assist on where the expression “Term” applied other than in Schedule 3. So I do not attach much weight to this further point.

109. More powerful in my view was his point that it is plain that what Avanti can invoice for (and only invoice for) are its Charges. See Clause 7 of the GSA which sets out a detailed invoicing and payment scheme, including an ability on the part of Avanti to charge interest on unpaid invoices and a procedure for dealing with good faith disputes on any particular amount invoiced. I fail to see how any of that can encompass or operate in relation to an invoice for a “reasonable charge”. Equally, I consider that paragraph 4 of Schedule 3 to the SOW contemplates defined amounts being charged.

110. In my view, what this means here (and notwithstanding the prima facie identification of the word “Term” as used in the SOW with that used in the GSA), the word Term must be aligned with the duration of the pricing agreed i.e. 7.5 years.

111. If that is right, any connected argument for an indefinite obligation to supply (i.e. beyond 7.5 years) simply falls away.

112. However, and in any event, EE has to make good its argument for an indefinite obligation to supply, whatever the term of the SOW. This is because if it is being said that the SOW imposed such an obligation without more, this would immediately conflict directly with Clause 2.3 of the GSA. Unless one is prepared simply to jettison that provision (which I am not) the only answer is to construe “Term” in the SOW for these purposes in a more limited fashion, so that there is no indefinite obligation to supply. Indeed, one would have to do that because of the precedence affording to the GSA in the event of a conflict with the Engagement Form or Order. See Clause 1.3 thereof.

113. Moreover, the “reasonable charge” point returns here, not now because it is commercially unrealistic to say that the parties would agree that if a PO was made it would be on the basis of a reasonable charge, but because it is equally unrealistic that they would agree that Avanti would be bound to supply on the basis of a reasonable charge, even without a PO.

114. For all those reasons, but subject to any factual matrix and some other points, I do not accept that EE can show that there was by virtue of the SOW itself, an indefinite obligation to supply, which persists even now. As a matter of construction, that contention seems to me to be plainly wrong.

115. Before considering factual matrix and some other points, I will deal with the two fallback positions advanced by EE.

116. The first was that, even if it was necessary to have a PO before Avanti was contractually committed to supply, all that was needed was PO1, to act as a trigger, as it were. However, in my judgement, there is no logic to that position. PO1 was limited to 4.5 years, and so if a PO was necessary to go beyond that, there would need to be a further PO, as indeed there was.

“The Supplier undertakes to accept all Engagement Forms and/or Orders where this clause 1.4 applies.”

118. Since Clause 1.4 does apply, as the SOW states, Mr Lavy KC submits that in this case, Clause 2.3 is redundant because Avanti must accept any Engagement Form or Order and has no choice in the matter. However, that cannot possibly be the correct interpretation of this sentence. If it was, it means that Avanti would be obliged to supply services at any price offered by EE in a PO and on any terms proposed by EE, realistic or not - and in fact even in the first 7.5 years. That does not make sense. What would make sense, and may be what this last sentence is driving at, is that if any of the “flowed down” terms were then to form part of an Engagement Form or Order, then, and to that extent, Avanti could not object to them and would have to accept them.

Factual Matrix and Other Points

121. Finally I examine any factual matrix or wider points which may have a bearing on the issue of the indefinite obligation to supply.

The EE-HO Contracts

122. According to paragraph 9 of RT1 (which I do not understand to be in dispute):

“In 2015, the United Kingdom Home Office contracted with EE to design and deliver a replacement for the existing Airwave terrestrial trunked radio (Tetra) network used by all police, fire and ambulance services across England, Scotland and Wales to communicate between the field and control rooms. The contract between EE and the Home Office was originally intended to have a six-year duration, with an option to extend it for one year until December 2022. Following delays to the programme, this contract was extended until December 2024.”

123. I refer to this contract as the First EE-HO Contract.

124. This contract clearly formed at least part of the background for the making of the GSA between EE and Avanti and there are references to the ESN in Annex 7 to Schedule 1 of the SOW.

125. Avanti makes the point that to the extent that the First EE-HO Contract was in the contemplation of the parties, as it must have been to some extent, as at 2016 there would be no need to be thinking of an indefinite obligation to supply, as opposed to one for 6 years. I see that, but the fact remains that it is far from clear that this Contract was the main driver for the GSA. EE says that it was not and I cannot gainsay that at this stage. So I do not think this argument takes the matter any further.

126. Avanti also invokes the duration of the First EE-HO Contract as an argument against EE’s point on Clause 1.4 of the GSA, discussed at paragraphs 117-120 above. On the basis that this was the relevant contract with the public body, if it was only to last until December 2022 and in the event lasted until December 2024, there would be nothing in that contract to drive any continuing obligation to supply beyond that. I see the force of that, although the more important points going to Clause 1.4 are those I have already made above.

127. I should add, for the sake of completeness that in 2024, the Home Office awarded a new 7.5 year contract to EE, apparently worth £1.29bn although this was not communicated to Avanti at the time (“the Second EE-HO Contract”).

Effect of an indefinite obligation to supply on Avanti

128. Avanti says that such an obligation would in fact be unworkable because it would mean that Avanti could be held to supplying services to EE even if the satellites originally specified were now unusable because their operating lives had expired, unless EE was prepared agree a change. EE’s answer to this is to say that the parties would no doubt act commercially in such a case to avoid this happening and come to an agreement. Further, Mr Lavy KC contemplated the possibility that there may be implied on the part of Avanti a right to terminate on reasonable notice, or even that the doctrine of frustration might apply. But as with the idea of an indefinite contract for services to be provided for a reasonable charge, the idea that a contract of this kind would be terminable on reasonable notice seems to me to be commercially very unlikely, where there are detailed express provisions for when it can be terminated. So I do think that Avanti has a point here.

EE’s ability to migrate to a new supplier

129. EE makes the point that if it was open to Avanti to terminate its services simply by not accepting any particular PO (which is its case) it means that EE would not have time to migrate properly to another supplier and it would be at significant cost, in circumstances where there were no provisions for any such transition which would bind Avanti.

130. As to that, Avanti’s evidence is that EE already owns the core network equipment on the ground, which the satellite services used to operate and the cost of redeploying that equipment would be modest in the course of what is now the First or Second EE-HO Contracts. Further, moving to different satellite operators is common in the market and there are many examples of migration from other operators such as Eutelsat and Intelsat, to Avanti (and vice versa). See paragraphs 61.1 and 61.2 of RT1.

131. This is not specifically responded to in LP2 but at paragraph 51 - 52 thereof, Mr Pardey says that although a new supplier has now been found, it would take at least three months to migrate the services to it although for the purpose of maintaining 999 services there could be a shorter timescale of 25 days. Such a period, however, would present risks and would be completely out of normal practice. A three month period would involve circumventing some best practice requirements (said to involve a 6-9 month period) and there could be delay factors. These points are made essentially in connection with the balance of convenience arguments that arise here but they are relevant when one considers the commerciality of a position whereby Avanti could effectively terminate its services by refusing to accept any further POs.

132. I can see the force of this submission but in my view it is weakened by the fact that in reality (as indeed one can see from the commencement of negotiations in May 2023) it was open to EE to put a time limit on the negotiations and thereby allow itself to effect a migration during the currency of an existing PO. Instead, EE decided to let the position of uncertainty going forward (because the pricing terms ran out in December 2023) continue throughout 2024.

133. It is true that at paragraph 37.1 of LP2, Mr Pardey says that the migration of services to a new satellite supplier would not have been possible while the migration to HYLAS 4 was ongoing in 2024 because all of BT’s design resources were engaged with that migration and there needed to be a stable static environment. The very earliest that any new supply activity could have occurred would have been on 15 April 2024 after completion of primary cell site migrations. I see that, but it is a limited point, since Mr Pardey agrees that there could have been a migration to an alternative supplier as from 15 April 2024. But more fundamentally, as Mr Parker KC pointed out in argument, there was nothing to stop EE from organising its POs in such a way as to give it time to find an alternative supplier if Avanti was not prepared to agree a further PO. After all, PO1 was for a period of 4.5 years and EE could have initiated discussions about the next PO during the period of PO1 and allow itself to switch supplier if Avanti was not prepared to make a commitment for the next PO. As he put it, all they needed to do was issue the next PO in sufficient time before the existing PO expired to enable them to arrange an alternative. In those circumstances, looking back at 2023, they may have decided not to agree a full migration to HYLAS 4 if that would cause logistical problems. So I do not accept that the fact that Avanti could terminate its services by declining to accept a particular PO means that the primacy given to Clause 2.3 of the GSA referred to above is in any way commercially absurd.

CCN5

134. EE relies upon the fact that CCN5 (cited at paragraph 43 above) states, among other things, that it “(b) Increases lifetime of space segment from 7 years (HYLAS 1) to 19 years (HYLAS 4).”, thereby implying that the parties must have been contemplating that Avanti would be providing its services for at least 19 years. I do not think that this point goes anywhere. The parties may well have considered that if all went well they would still be dealing with each other for 19 years but that does not override the primacy of Clause 2.3 of the GSA, nor does it suggest any commitment for 19 years. It is just pointing out that there is the advantage of now having a satellite which would last much longer than HYLAS 1.

The GSA/SOW as an “evergreen” contract

135. At paragraphs 13 and 14, Mr Pardey asserts that the GSA and the SOW amounted to an “evergreen” contract, whereby the provision of services continued indefinitely unless and until terminated. He says that it was typical for EE/BT contracts with others to be of this form. Further, such evergreen contracts would not require the indefinite provision of services because as technology moves on parties terminate, amend or agree to end their service contracts.

136. However, I do not consider that this takes EE anywhere. First, if the “evergreen” contract is one whereby it renews automatically unless one or other party gives notice of termination (see for example, the contract in Howard Hagen & Ors v. ICI Chemicals and Polymers Ltd & Ors [2002] 1 Lloyd’s Rep PN 288, at 294, where there was a renewable term of five years with the option to terminate on one year’s notice after the fourth year), this proves too much because the GSA/SOW is not such a contract. There is no right (on EE’s case) for Avanti to terminate a fixed term on notice and without cause. Second, in any event whatever may have been EE/BT’s practice in relation to other contracts, the focus for present purposes must be on this one.

Conclusion on factual matrix and other points

137. It follows from what I have said above that these further points do not assist EE to supplant the primacy of Clause 2.3 of the GSA, and indeed they tend to support Avanti’s position instead.

Overall Conclusion on Serious Issue to be tried

138. For all the reasons given above, I consider that the interpretation of the GSA/SOW contended for by EE is plainly wrong and does not give rise to a serious issue to be tried.

139. On that basis, questions relating to the adequacy of damages and balance of convenience do not arise and this application for an injunction must be dismissed.

140. I am grateful to Counsel for their succinct and lucid oral and written submissions.