British

and Irish Legal Information Institute

Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

England and Wales High Court (Queen's Bench Division) Decisions

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> England and Wales High Court (Queen's Bench Division) Decisions >> Scumaci v Martin [2021] EWHC 2833 (QB) (22 October 2021)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/QB/2021/2833.html

Cite as: [2021] EWHC 2833 (QB)

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

QUEEN'S BENCH DIVISION

Strand, London, WC2A 2LL |

||

B e f o r e :

____________________

| GIOVANNI SCUMACI |

Claimant |

|

| - and - |

||

| BARRY MARTIN |

Defendant |

____________________

Mr Patrick Williams QC (instructed by BLM) for the Defendant

Hearing dates: 8th October 2021

____________________

Crown Copyright ©

- By leave of Mrs. Justice May granted on 11 June 2021, the appellant/claimant appeals against the judgment of Master Sullivan dated 1st December 2020 whereby she dismissed his claim for damages arising from an accident that occurred on 18 April 2016.

- The accident occurred in a carpark near Lake Windermere at about 3pm in the afternoon. The claimant and his girlfriend had parked their rental car in the carpark and the claimant had gone to a ticket machine to pay for the parking. As he returned to his car, he noticed something protruding from the front of the car - according to the defendant, Mr Martin, this was a piece of rubber valence which had become detached because the car had, for example, been driven too fast over a speed bump – and the claimant was bending down in front of the car to inspect what it was, with his girlfriend by his side. In the meantime, the defendant, Mr. Martin, who had been boating on the lake with members of his family, returned to his car which was parked a short distance away from the claimant's rental car. Mr Martin emerged from the parking space and then turned to his right to follow the one-way system out of the carpark. This involved him driving past where the claimant was bending down inspecting the rental car. Putting it neutrally, there was contact between the claimant and the defendant's Range Rover and this resulted in the claimant's left foot being run over by the rear wheel of the car, causing him to suffer a very nasty fracture to his foot and ankle and leaving him with a long-term injury. The issue at trial was whether the defendant negligently drove too close to the claimant or whether, on the defendant's case, he left sufficient room.

- The carpark in question is relatively small, laid out in a loop and with a one-way system. There are two rows of parking spaces so that cars entering the carpark drive down one row, turn at the end and drive back along the other row to the exit. The accident occurred in the row leading back to the exit. The parking bays are not perpendicular to the row but at a slight angle so that cars parked with their front end to the road are facing slightly towards oncoming cars with the front offside of the parked car being slightly forward into the road than the front nearside.

- At the point where the accident occurred, there were cars parked only on the offside with the nearside occupied by the ticket machine and some bushes and trees. Thus, the road was somewhat wider than further down towards the exit where there were parking bays on both sides. A "Locus" report from a jointly instructed expert showed that the width of the road between the end of the painted white lines designating the parking bays on the right (offside) and the curb on the other side was some 5 metres. The width of the Range Rover was 2.2 metres (including the wing mirrors) leaving a total leeway of about 2.8 metres at that particular point. If a Range Rover was being driven absolutely in the centre of the road, equidistant from the curb and from the end of the parking bays, the distance on either side of the car would be 1.4 metres.

- After the accident, a police officer, PC Victoria Haley attended: she received the call to attend at 15:06 and arrived at 15:10. She saw the claimant lying on the floor and the Land Rover was parked a short distance in front of the claimant with four people in the car (Mr Martin, the defendant, his brother and their wives). In her statement, PC Haley said that she spoke to the claimant to see how he was and although he was in a lot of pain he was conscious and able to give her an explanation. In the Police Collision Report she recorded this as follows:

- At trial, the claimant's case was not consistent with the account given to PC Haley which the claimant said was wrong and not the account he had given. He said that he had not stumbled but that he had stood up from his bending position, moved his leg a few inches and turned the angle of his foot slightly and had then been hit on the back of his left leg by the car and been dragged onto the floor. He denied having stumbled and said he had lost balance only because the car ran over his left leg. He described the car running over the side of his left foot. His evidence was that the Range Rover was so close that, had he stood up earlier, he would have been hit by the car's wing mirror. This was not an account which the Master accepted. The claimant's girlfriend, Ms. Scardaoni, said that the first thing she knew was when she heard a bang and looked to her left and she had not been aware of the Range Rover before this. She said that she would nonetheless have known if the claimant had stumbled or moved significantly and she was of the view that he did not.

- The defendant, Mr Martin, gave evidence that he had seen the claimant bending over looking at the front of his car as he was returning to his own car which was four or five bays past where the claimant's car was parked. He said he pulled out of the parking space forwards and turned to the right taking up a position in the road. He did not approach the claimant at an angle but was driving straight and he said that there was enough space on the left and the right for him to drive down the road safely. He said he was aware of Mr. Scumaci still bending over the front of his car as he passed. I shall return to his evidence about the gap which he left between the offside of his car and Mr Scumaci later in this judgment. His evidence was that he had left sufficient space to the offside of the Range Rover to have passed safely but for the claimant's own actions and that his driving had not been negligent.

- In her judgment, the Master set out the legal test to be applied stating:

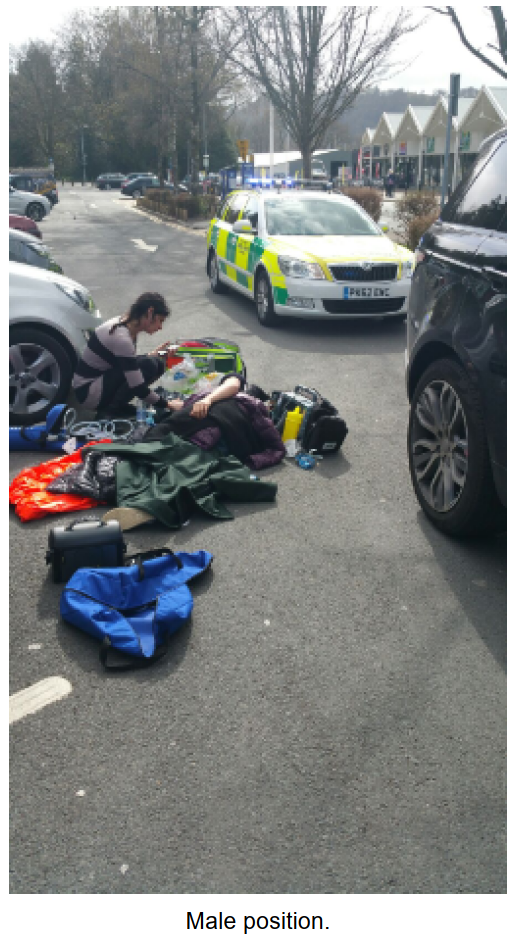

- In the evidence before her there was a photograph taken by PC Haley showing the position of the claimant lying in the road and being attended to and the position of the rear of the Range Rover. This photograph has had such significance, both in the court below and on this appeal, that I reproduce it here:

- This shows that the Range Rover had stopped a very short distance forward from the point of the accident, about the width of one parking bay. This was consistent with the defendant's evidence that he had been going very slowly and driving cautiously. The short distance which the Range Rover had travelled meant that there was no opportunity for the defendant to have steered to his right or his left and the learned Master accepted he had stopped in the line that he had taken when approaching the claimant.

- The Master considered that this photograph therefore presented the most objective evidence of the position from which the car had come. She said:

- The Master rejected the claimant's evidence and accepted the evidence of PC Haley that, that following the accident, when she spoke to him, he said that he was bending down near the car, stood up and fell against the passing Range Rover, stumbled and that his left lower leg got run over by the car and that his view was that he took a step at the wrong time and accepted it was a freak accident and did not blame the driver. She accepted, and found as a fact, that the claimant had spoken words to that effect to the police officer. The learned Master also found the evidence of the defendant, Mr Martin, to be unreliable, referring to the different accounts which he had given as to the distance of his car from the front of the claimant's rental car and the claimant himself. She referred to the differences between what he had said in his witness statement and what he said in evidence and also the difference between what he said in his witness statement and in his defence. She then said this:

- In support of this appeal, Mr Audland QC (who did not appear below) submits that the Master's approach towards, and assessment of, the evidence was flawed. In particular, he submits that, rather than reject the defendant's evidence altogether, she should have accepted and taken into account the significant concessions which he made in cross-examination. Had she done so, she would have concluded that the offside of the defendant's car was not more than 3ft from the end of the parking bays to his right, that the crouched figure of the claimant was within that 3ft and that the defendant was accordingly driving too close to the claimant, indeed negligently close, given the amount of room to the nearside. Furthermore, he submits that it was wrong in principle for the Master to have decided the case on the basis of the photograph when

- In support of his submissions, Mr Audland took me through the way that the defendant's case developed in the course of his oral evidence, reflected in the change in the defendant's case in the closing submissions of Mr Vincent for the defendant. The starting point was the agreed evidence of the jointly instructed expert, Mr Tetley which established that the width of the road at or around the point of the accident was 5 metres. The width of the Range Rover car being driven by the defendant was agreed to be 2.2 metres including the wing mirrors, or 2 metres without the wing mirrors. Mr Audland then went through the way that the defendant's case changed and developed through these proceedings:

- It was in this context, Mr Audland submitted, that the Master accepted the submission of Mr Vincent that the photograph was the best evidence from which she could judge the distance left by the Range Rover as it passed the claimant, Mr Scumaci. She found that although the gap was not as much as 6ft, the actual gap was not so close as to be negligent. Mr Audland submitted that the clear evidence of the defendant had been that the gap between the offside of the Range Rover and the cars parked to the right was about 3ft, that Mr Scumaci was within that 3ft, that the Master should have so found and, had she done so, she would have found that, with a gap of less than 3ft to Mr Scumaci himself, the defendant had driven negligently close to him and that this was causative of the accident.

- For the defendant, Mr Vincent submitted that, in Mr Archer's closing submissions in the court below, he had conceded that whether the defendant was driving too close was an evaluative judgment rather than a specific distance. Thus, there was the following exchange:

- Building on that, Mr Vincent submitted that the photograph relied upon by the Master effectively showed where the Range Rover would have been at the time it passed the claimant and how much room was left and what the Master did in her judgment was what she had been invited to do by Mr Archer, namely make a value judgment as to whether sufficient room had been left.

- Mr Vincent further submitted that the Master was justified in not accepting the defendant's evidence in cross-examination that he was less than 3ft from the claimant as the defendant passed the claimant because:

- Furthermore, Mr Vincent drew on the evidence as to what was said at the time of the accident, namely the claimant's acceptance that it is his own fault, that he had stumbled and that it was a freak accident, supported, said Mr Vincent, by the photograph of the scene. In those circumstances the Master was entitled to rewind the photograph by 2 seconds and ask herself whether it depicted a driver not taking reasonable care in all the circumstances, that she was wholly entitled to reach the conclusion that she did, on the evidence, and to suggest otherwise is unrealistic.

- Mr Vincent further drew attention to the fact that the claimant's primary case, that there had been no step backwards or stumble but that the defendant had hit him with the motor car whilst he was stationary, was rejected by the Master and properly so. The case now relied on by the claimant is therefore essentially a secondary case, namely one which suggests that even if the claimant did unexpectedly step back and stumble, the Range rover was still too close to him and was a source of danger when it should not have been: Mr Vincent submitted that the rejection of the case was all the more understandable and reasonable when it was not the claimant's primary case and when, therefore, the Master was not getting any helpful evidence from the claimant himself.

- Furthermore, Mr Vincent relied upon the defendant's evidence that the course which he had taken was not based solely on the immediate distance to his left and right but was also partly governed by what was ahead, namely a row of cars parked on the left so that there were cars parked on both sides with a significantly narrower gap to pass down than the gap at the immediate location of the accident. He submitted that it was reasonable for a driver to take a straight course which took account of the conditions a short distance ahead rather than to zigzag, as it were, where the road widened and narrowed and this explained the context for the Judge's findings and increased the difficulty for the claimant that the conclusion reached by the Master was one no reasonable Judge could have taken.

- Finally, Mr Vincent did not accept that the Master had engaged in a reconstruction of the accident: he submitted her task was not to decide how the accident had happened but whether the defendant had left enough room. She properly and reasonably used the photograph to judge whether sufficient room had been left and her conclusion represented a sound evaluation of what was, in fact, primary evidence.

- In my judgment, the basis for this appeal, namely that the learned Master should have found that the distance between the offside of the Range Rover and the cars parked to the right was about 3ft, that the claimant was within that 3ft and that the Range Rover was therefore dangerously close to the claimant, is too simplistic. Of course, the distance left by the defendant to his offside was an important aspect but, as the Master put to Mr Archer in closing, and as Mr Archer accepted, the task of the Master was essentially an evaluative one, namely whether, in her judgment, sufficient room had been left. There were a number of strands to the making of this value judgment:

- the evidence of the defendant in cross-examination, and the concessions which he made, of course; but also

- the photograph and what it showed;

- what was said by the claimant at the scene about how the accident occurred and the Master's acceptance of the police officer's evidence in that regard;

- the driving conditions generally including not just the width of the road at the point of impact but also the width a very short distance further ahead where there were cars parked to the left;

- the very slow speed at which the defendant was driving;

- the fact that generally there were pedestrians around, this being a carpark, so that even if there were no pedestrians actually to the near side at the moment the defendant passed Mr Scumaci, pedestrians could emerge from the left at any moment, particularly a little distance up ahead where there were parked cars on the left.

- In those circumstances, despite the powerful submissions of Mr Audland that the Master should have taken greater account of the significant concessions made by the defendant in his evidence as to the distance which he had left to his offside, I am not persuaded that the Master's evaluation and her judgment were wrong. Contrary to Mr Audland's submissions, the Master did not draw inferences from primary findings of fact or, indeed, venture beyond inference and into conjecture, in the way being referred to by Lord Wright in Caswell v Powell Dufferin Collieries [1940] AC152. In my judgment, Mr Vincent's submission that the photograph was primary evidence is correct because it showed where the Range Rover had come to a rest, within a very short distance of the point where it collided with Mr Scumaci, and could therefore properly be used as part of the value judgment as to whether sufficient room had been left. I agree with Mr Audland that it might have been better if the Master had tackled the defendant's concessions head-on and made a finding of fact as to the distance which the defendant had left to his offside, the distance between the offside of the car and Mr Scumaci and whether that distance was negligent. I do not accept, however, that this would inevitably have led to a finding of negligence. In my judgment, the Master was entitled to take a wider view of the way in which this accident occurred and the concessions made by the claimant at the scene were powerful ones from the defendant's point of view. Mr Scumaci contested at the trial that he had said the words which the police officer recorded but the Master accepted that both he had said those words and had intended them at the time so that he had indeed blamed himself for the accident, not Mr Martin, the defendant. It was inconceivable that Mr Scumaci would have said those words had he been struck by the car whilst stationary inspecting the front of his own car. Thus the acceptance of the police officer's evidence and its consequences were fatal to the claimant's case as it was being put at trial. In those circumstances, the case for the claimant became a very difficult one despite Mr Archer's skilful cross-examination of the defendant and the concessions which he thereby elicited as to distance.

- The value judgment which the Master made was, as it seems to me, archetypically one for a first instance judge who has heard and considered all the evidence and I do not consider that the case has been made out that the Master's judgment, and the way that she reached that judgment, was one which no reasonable judge could have made. For the purposes of this appeal, the claimant must show that the Master's decision was wrong. Whether I, or another judge, would have reached the same decision is not to the point: in the end, I have not been convinced by Mr Audland's submission that the Master's decision was wrong and, in those circumstances, the appeal must be dismissed.

Mr Justice Martin-Spencer:

Introduction

The circumstances of the accident

"[He] stated he was bent down looking at his car, stood up and fell against a passing car, he stumbled and his left lower leg got run over by the vehicle."

On the first page of the collision report in the section headed "How Collison Occurred" she summarised her understanding as follows:

"Vehicle 01 has pulled out of parking space and has been heading to exit carpark. Pedestrian, who was inspecting the front of his car, has stood up and stumbled into the rear driver's [side] door of vehicle 01. He [has] then stumbled and the vehicle's rear tyre has ran over left lower portion of pedestrian."

The evidence at trial

The Master's Judgment

"The legal test that I have to apply is whether the defendant's (Mr Barry Martin) driving fell below that of a reasonably prudent driver. Such a driver has to take into account the actual and potential hazards and has to guard against possible negligence of others when experience shows such negligence to be common. So a reasonably prudent driver must guard against foreseeable actions of pedestrians, be they perfectly reasonable and normal actions, or folly."

No complaint is made on behalf of the appellant of that direction of law that the learned Master gave herself.

"I do accept that the perspective of the photograph does not make precise conclusions easy and I have to take into account the angle it is taken from and the perspective that gives when assessing it. It does show, in my judgment, that the Range Rover stopped within the next parking bay from the one Mr Scumaci parked in. The parking bays are 2.5 metres wide according to the Locus Report, so the car did not travel a greater distance, in my judgment, than 2.5 metres following the collision and probably significantly less. That, I have to say, is consistent with all of the evidence from the witnesses, that Mr Martin was driving very slowly through the carpark and he was driving at less than 5 miles an hour."

"30. So I am left with what seems to me the best evidence, which is the photograph at page 45 of the bundle. It seems to me the best evidence is what I can take from that photograph. I accept that Mr Martin was driving roughly in a straight line and he did leave a gap between his car and Mr Scumaci. I cannot make a reliable finding on the exact distance in feet or metres. The evidence is not that precise and probably my estimation of what a foot or metre is, is not sufficiently precise. But it seems to me that it is not as much as 6 foot, suggested by Mr Vincent, but on the view from the photograph, the gap left between the Range Rover and Mr Scumaci is not so close as to be negligent. That is consistent with the impression given by Mr Scumaci at the time of the accident and as recorded by PC Haley. It seems to me that the distance was one that is within the range that a reasonably prudent driver, having seen the bent figure of Mr Scumaci and what his foreseeable movements might be, would have left. It is certainly not as far to the left as it could have been but I accept that is not the correct test as reasonably prudent drivers may have taken up a range of different positions in the road. He did not drive so close, in my view, as to be negligent. I do not accept, as submitted by Mr Archer, that even if Mr Scumaci did stumble, the car was too close, as such a stumble that might have occurred should have been anticipated and taken into account. Some movement from the crouched person would be foreseeable but this was a driver, in my judgment, who was driving very slowly and leaving a reasonable gap to account for that foreseeable movement."

On that basis, the learned Master found that the defendant was not negligent and dismissed the claim.

The Appellant's submissions

(i) The photograph was not evidence of the accident

(ii) The photograph was an unsafe basis to decide the case and led her away from other evidence which was good objective evidence

(iii) It was unfair to rely on the photograph when the claimant had sought and been refused reconstruction evidence from an expert, particularly when the defendant's case as to what the photo showed had changed in the course of the trial

(iv) The Master accepted that it was not possible to judge distance accurately from the photograph.

(i) At paragraph 5(f) the defence, it was pleaded that "the defendant positioned his car in the lane as to leave the maximum possible space on his offside. There was only 1 or 2 feet of space between the defendant's car and the cars parked to his nearside and over 3 to 4 feet of space to the defendant's offside."

(ii) In his witness statement, the defendant said

"27. My car was moving forward at what I would describe as a crawl. I was progressing very cautiously.

28. I therefore left a gap of about 3 feet between the offside of my car and where the man was bent over.

29. There was about a foot between the nearside of my car and traffic parked in bays to my left."

(iii) In the skeleton argument prepared for the purposes of the trial below, Mr Vincent stated: "The defendant's case is that he left at least 3 feet between the offside of his vehicle and the claimant – see paragraph 5(f) of the defence and paragraph 28 of the defendant's witness statement."

(iv) In his evidence, the defendant conceded that there was less than 3 feet between the offside of his car and the claimant who was within the gap of 3 feet between the offside of the car and the cars parked on the right. For example, at page 69 of the transcript of the first day of the proceedings in the court below, the defendant conceded that there was 3 feet to the offside with the claimant within those 3 feet and he said "I could have gone off further to the other side, of course I could, but there was enough room for me to pass him with it, with plenty of room." Mr Archer, for the claimant, put that if the claimant was within the 3 feet gap to the offside he was going to take up a lot of that room so that the defendant would have been very close to him, but the defendant demurred saying "no, I disagree."

(v) This led, Mr Audland submitted, to Mr Vincent, in closing, effectively abandoning his client's evidence and relying solely on the photograph submitting: "Just about every issue in this case can and be resolved in the defendant's favour just by looking at this photograph taken at the time. … and the first thing you should find, because in my submission it is obvious, is that when it stopped, this vehicle was about 5 to 6 feet away from that white line." By which he meant the end of the white line delineating the parking space. The Master asked how she gets 5 to 6 feet and Mr Vincent responded: "By looking at it, knowing the dimensions of a vehicle, knowing the dimensions of Mr Scumaci, who is 5'7. It is plainly not 1ft or 2 or 3, in my submission, and you do not need evidence of measurement to reach what, in my submission, is a common-sense judgment that that is about what it shows."

The Respondent's submissions

"Master Sullivan: you say even on the defendant's case he was driving too close. Yes. I mean, that is the key question I have to decide, is whether or not, given the standard of reasonable prudent driver, he was driving too close.

Mr Archer: Yes.

Master Sullivan: There might be a difference of opinion whether 3-2ft, 3ft, 4ft, 5ft is too close and exactly what that measurement was, but it is an evaluative judgment of whether or not he was too close…

Mr Archer: Exactly Master.

Master Sullivan: Rather than a specific distance.

Mr Archer: Exactly Master. I do not know if I can put it any better than that."

(i) She saw and heard the defendant's evidence and found it be unreliable in relation to measurements because he had been inconsistent.

(ii) The defendant had always maintained that he had left enough room.

(iii) No part of the defendant's evidence made it inevitable or likely that his evidence that the claimant was within 3ft was correct and that other parts of his evidence were wrong.

(iv) There was no reason for the Master to alight on that concession and accept it rather than any other part of the defendant's evidence.

(v) Contrary to Mr Audland's submission, the claimant's case is not supported by subjective agreed evidence. Only the dimensions of the carpark and of the width of the Range Rover were agreed. The crucial question was where the Range Rover was and there was no other evidence supporting the distance conceded by the defendant.

Discussion

These were all considerations which the defendant said in his evidence he was taking into account when he adopted the course or trajectory which he did, and which he considered, at the time, to be a safe one, particularly given the very low speed at which he was travelling. These were also all considerations which the Master was entitled to take into account in making her value judgment as to whether the defendant's driving had been negligent.