Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

England and Wales High Court (Queen's Bench Division) Decisions

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> England and Wales High Court (Queen's Bench Division) Decisions >> Parker v McClaren [2021] EWHC 2828 (QB) (22 October 2021)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/QB/2021/2828.html

Cite as: [2021] EWHC 2828 (QB)

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

QUEEN'S BENCH DIVISION

Strand, London, WC2A 2LL |

||

B e f o r e :

(sitting as a Deputy Judge of the High Court)

____________________

| LAUREN PARKER (acting by her Litigation Friend, Nigel Parker) |

Claimant |

|

| - and - |

||

| CLIVE MCCLAREN |

Defendant |

____________________

Jacob Levy QC (instructed by Weightmans LLP) for the Defendant

Hearing dates: 28th, 29th, 30th June & 1st July 2021

____________________

Crown Copyright ©

- At about 11:20 pm on Saturday 6th May 2017, there was a road accident in the centre of the City of York. The collision occurred just to the east of the bridge over the River Ouse, along which runs Bridge Street which then becomes Low Ousegate after the river crossing. The Defendant, a licensed private hire driver, was driving a Skoda Octavia car carrying two passengers to a destination in the city centre. The Claimant, then aged 23, was on a night out with friends. The accident occurred when the Claimant attempted to cross the road along which the Defendant's car was travelling. The car hit the Claimant, resulting in her being thrown to the ground and striking her head. She suffered catastrophic injuries as a result, including a traumatic brain injury and resulting physical and mental disabilities.

- By this claim, issued on 16th December 2019, the Claimant, acting by her father as Litigation Friend, makes a claim for damages against the Defendant arising from his allegedly negligent driving. The essence of the allegations made is that the Defendant was travelling too fast in the particular circumstances and that he failed to keep an adequate lookout. In response, the Defendant contends that the accident was caused or contributed to by the negligence of the Claimant. The essence of the Defendant's case is that the Claimant failed to notice the Defendant's approaching car and entered the road when it was unsafe to do so.

- By an Order made by Master Gidden on 16th July 2020, the claim was listed for a four-day trial on liability only. Directions were also given for expert evidence in the field of accident reconstruction. The trial took place before me at the Royal Courts of Justice between 28th June and 1st July 2021. At trial, the only witness of fact relied upon by either party was the Defendant himself. The Claimant has not been able to give an account of the accident because of her injuries.

- The parties' accident reconstruction experts, Dr John Searle (for the Claimant) and Mr James Wade (for the Defendant), who had prepared written reports and a joint statement, both attended trial and gave evidence orally. Dr Searle is a Chartered Engineer who was for 25 years a senior employee, and latterly the Scientific Director, of the Motor Industry Research Association, with a considerable research background into various aspects of motor accidents. Mr Wade is also a qualified engineer and has since 2014 been a specialist in the investigation of road traffic collisions and their reconstruction at Hawkins & Associates Ltd, a firm of forensic scientists.

- I record my gratitude to the parties' legal teams, and in particular to both Leading Counsel, for the clarity and care with which their respective cases were presented at trial.

- In Barrow & Others v Merrett & Another [2021] EWHC 792 (QB) ("Barrow v Merrett"), Mr Richard Hermer QC, sitting as a Deputy High Court Judge, said this at the beginning of his judgment:

- I respectfully adopt those observations as to the task of the Court in a case such as this. To similar effect were the observations of Coulson J in Stewart v Glaze [2009] EWHC 704 (QB) ("Stewart v Glaze") at [5-10]. I have particularly borne in mind what Coulson J said at [10] of his judgment, that it is "the primary factual evidence which is of the greatest importance in a case of this kind" and that it is important not to elevate the expert evidence into a framework against which the defendant's actions are to be judged with mathematical precision.

- As has also been observed in the decided cases, the Court is faced with a particular difficulty in making findings of fact when the severity of a claimant's injuries makes it impossible for them to give evidence about the circumstances of the accident. In the present case, that difficulty is compounded by the lack of evidence from any witness to the accident other than the Defendant himself. Nonetheless, the Court must determine the dispute put before it and so make findings of fact based on the evidence (including the expert evidence) which the parties have adduced.

- There is a very significant measure of agreement between the parties about the circumstances leading up to the accident and there was no challenge made on behalf of the Claimant to the central elements of the account given by the Defendant. I shall therefore begin by setting out the background, insofar as it is not controversial, based upon the evidence given by the Defendant.

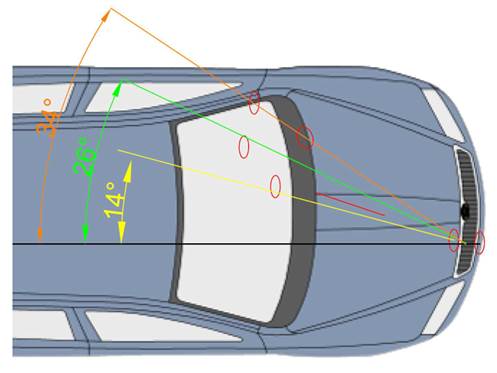

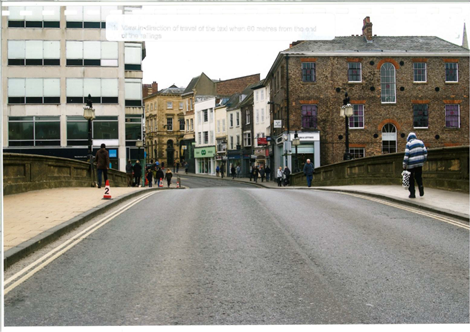

- Bridge Street / Low Ousegate is a single carriageway road in the centre of the City of York, which runs from east to west and includes a bridge over the River Ouse. It is a two-way street, i.e. traffic can travel in both directions along the road. The carriageway is just over 7 metres wide. At the material time, it was subject to a 30 mph speed limit. Just across the eastern end of the bridge there were bars and restaurants, including on the south side of the road a "Slug & Lettuce" bar and on the north side of the road a "Yates' Wine Bar". I have included in the Appendix to this judgment two images of the accident scene taken from the bridge by the parties' accident reconstruction experts, one taken in the day by Dr Searle (Image 1) and another taken at night by Mr Wade (Image 2). These images were both taken some time after the accident.

- The Defendant was born in 1937 and passed his driving test when he was 18 or 19 years of age. He had been a professional driver for his entire working life and prior to the accident had worked as a licensed private hire driver in the City of York for about 40 years. After reaching the age of 65, the Defendant was required to provide a medical certificate in order to renew his private hire licence. He had undertaken a medical assessment in about January 2017, which involved an in-depth vision assessment. The Defendant wore glasses when driving but did not have any other conditions that affected his ability to drive. The Defendant's vehicle was a grey Skoda Octavia estate car, registered in 2007. It was 4.7 metres long, 1.8 metres wide and had a maximum height of 1.5 metres. It was equipped with anti-lock brakes. At the time of the accident, the Defendant was driving with his dipped front headlights on.

- In his evidence, the Defendant described himself as a "night owl". He enjoyed working at night, when the traffic was lighter, and preferred to rest during the daytime. His routine was to work on Thursday, Friday and Saturday nights, starting at around 6:00 pm and finishing at 3:00 am, or at the latest 4:00 am. The Defendant worked for a local taxi company, York Cars, which would provide him with bookings by radio. He did not drive with a satellite navigation system; he knew York very well. He did have an electronic device attached to his dashboard which would display details of the jobs and fares. On the night of the accident, the Defendant had started his shift at around 6:00 pm. At about 9:00 pm, he drove passengers some 20 miles to the town of Harrogate. On returning, he had a break of about 30 minutes to eat and drink. He was due to drive back to Harrogate to collect the same passengers later in the evening.

- Prior to the accident, the Defendant collected two passengers from Leeman Road, on the western side of the City of York. They wished to be driven to a bar across the River Ouse on King Street, very close to the scene of the accident. The passengers were seated in the back seat of the Defendant's car. There was no-one in the front passenger seat. In order to travel to drop the passengers off near to the bar on King Street, it was necessary for the Defendant to cross the River Ouse from west to east, using Bridge Street. It was the Defendant's intention to drop off his passengers a short distance from where the accident occurred. He was very familiar with the journey; on a busy weekend he might drop off passengers in this area on 10 or 12 occasions.

- It was a very busy Saturday evening in the centre of York, with people enjoying the bars and pubs. The pavements either side of the end of the bridge across which the Defendant's car travelled were full of people. The Defendant was aware that there was a large number of people on both the northern and southern pavements at the eastern end of the bridge, although he thought that there were fewer people on the northern side. There were double yellow lines marked on both sides of the road at the eastern end of the bridge, and no parked vehicles on either side of the road. There were no vehicles either in front of or behind the Defendant's car. At the end of the bridge on the northern side of the pavement there were pedestrian railings which extended for a short distance, ending at about the point where the accident occurred.

- It is agreed that the accident happened following the Claimant leaving the southern pavement, apparently seeking to cross the road to get to the northern side. This would have resulted in her coming from the pavement which was to the offside (i.e. the driver's side) of the Defendant's car. There is no evidence about what clothes or shoes the Claimant was wearing when the accident occurred, or about whether she was wearing any jewellery. The Defendant was asked about this by Mr Maskrey, but he could not remember. The Claimant had travelled just over five metres from the offside kerb edge to the point of collision, which was on the Defendant's side of the road. The point of impact was about 0.2 metres to the offside of the centre line of the Defendant's vehicle.

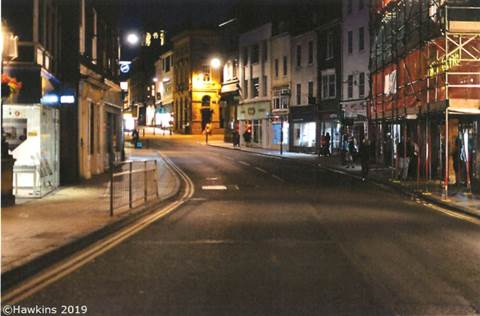

- After the initial impact, the Claimant moved across the front of the car. The Claimant was then thrown both forward and laterally (i.e. towards the nearside kerb). The precise extent of the 'lateral throw' is a matter of dispute. There was some damage to the front of the Defendant's car, but the windscreen was not broken. As I have already indicated, the Claimant struck her head on the ground and suffered a traumatic brain injury. An ambulance was called, and the Claimant was taken to hospital. The police also attended the scene and took photographs and measurements. Later, they conducted tests on the Defendant's car. Image 3 in the Appendix to this judgment is from Mr Wade's report and shows, superimposed, the position of the Defendant's car after the accident and the point of collision.

- Shortly after the accident, at 12:52 am on the morning of 7th May 2017, the Defendant was interviewed under caution at Fulford police station. The interview was conducted by a North Yorkshire police traffic officer and lasted 11 minutes. A solicitor was present. The interview was tape-recorded. A transcript was exhibited to the Defendant's witness statement and he confirmed that it was accurate. During the police interview, the Defendant said that he had been approaching the scene of the accident with caution due to the large number of people and the possibility of someone jumping out in front of him. He said that he had suddenly seen a girl running across the road and that he had hit the brake pedal but that an accident was unavoidable.

- I shall now set out the Defendant's evidence, insofar as it addresses issues that are the subject of controversy. As is apparent from what I have said above, the main issues between the parties relate to the speed at which the Defendant's car was travelling, the opportunity which he had to observe the Claimant prior to the accident, and the Claimant's movements prior to the collision.

- The Defendant's evidence was that although the speed limit was 30 mph, he was not travelling that fast. He was not driving any differently to how he would normally drive when going across the bridge. He explained that it was not possible to build up any degree of speed because of the traffic lights which he had passed through before getting onto the bridge and the sharp right turn that he would have been making shortly after crossing the bridge, as well the presence of a pedestrian crossing point controlled by traffic lights. In his witness statement, the Defendant said that at the time of the accident he had not got out of second gear and that he was not driving faster than 20 mph. He said that it felt that he was driving at around 15 mph.

- When cross-examined by Mr Maskrey, the Defendant accepted that it would not have been appropriate to travel at anything like the 30 mph speed limit in the circumstances, given the presence of so many pedestrians. The Defendant said that, in his experience, at this time of night pedestrians would sometimes jump out into the road along this particular street and that he was therefore wary of this happening. He said that he would look out for this, looking at the pavements on both sides of the road, and he would hope that pedestrians would not do it.

- When questioned by Mr Maskrey about the speed at which his car had been travelling prior to the accident, the Defendant said that he considered that he was travelling at a safe speed, and that he was certain that he had been travelling at 15 mph. He said it would be incorrect to say he was travelling at close to 20 mph. He accepted that it would not have been safe to travel at more than 15 mph, which was in his view the appropriate speed in the particular circumstances. The Defendant said that he would know the speed that he was doing without looking at the speedometer and that because of the road layout he would not have been doing more than 15 mph.

- The Defendant maintained in his evidence that he was keeping a lookout for pedestrians on both sides of the road. He thought that the northern side of the pavement would have been less busy, in terms of pedestrians, than the southern side from which the Claimant came. He accepted that there was nothing obstructing his view of the pavement. He said however that he did not see the Claimant leave the southern pavement. In his oral evidence, he said that prior to the accident he did see someone running fast on the southern pavement, but it looked like they were running away from his vehicle. He did not slow down. He had then picked the Claimant up in his headlights. He did not remember seeing the Claimant on the pavement before she entered the road. He maintained that the Claimant was running when he saw her. He said that he first saw the Claimant when she was in the road in front of his car; the car's headlights had lit up her face. He then "hit the brakes", as fast as he could. The Defendant's evidence was that he had "hit the brakes" before the impact between his car and the Claimant. He agreed with Mr Maskrey that seeing the Claimant and "hitting the brakes" happened almost instantaneously. After the initial impact the Claimant moved onto the car's bonnet.

- When re-examined by Mr Levy, the Defendant said that he had not looked at his speedometer and that the speeds that he had given in evidence for his vehicle were estimates based on his experience. He would ensure that he was travelling slowly when coming over the bridge because people would jump out. He was not sure whether the person he had seen running on the pavement was the Claimant; he might have lost sight of her until she was picked up in the headlights.

- As I have already noted, both parties instructed accident reconstruction experts who gave evidence at trial. I will not set out the conclusions reached in the original expert reports in any great detail, because both experts completed a very helpful and detailed Joint Statement.

- In his initial report, Dr Searle reached the following conclusions, in summary:

- In his initial report on behalf of the Defendant, Mr Wade reached the following conclusions:

- Following the preparation of their respective reports, the parties' experts conducted a discussion by telephone on 5th March 2021. They prepared a Joint Statement, which was completed by an exchange of emails. The Joint Statement, which runs to 40 pages, makes the following material points:

- The following points of significance emerged during the oral evidence of the experts at trial:

- I have already noted that the only witness of fact called by either side at the trial was the Defendant himself. There were clearly many other people present at the scene apart from the Claimant and the Defendant. Some of them gave written statements to the police, which were shown to the parties' accident reconstruction experts. Although these statements formed the basis of some of the experts' conclusions, those who made them were not called as witnesses of fact at the trial and the written statements were not otherwise relied upon as evidence at the trial by either party. I have not, therefore, taken these statements into account and nor was I invited to by either Mr Maskrey or Mr Levy. No explanation was given by either party for not calling these witnesses at trial and I was not asked to draw any adverse inference against either side for not having done so.

- I found the Defendant to be a credible witness who was doing his best to assist the Court in determining what had happened on the night of the accident, based on his recollection of events. That is not to say, however, that his evidence was for that reason also reliable in all respects, particularly where he was giving evidence more than four years after the accident (see the discussion at [31-38] of Barrow v Merrett, where the Deputy Judge noted the caution that should be applied when considering statements made in litigation as to highly traumatic events lasting only a few seconds which occurred several years beforehand). But I do not consider that the Defendant was trying to mislead me in any way about what happened; indeed, although well aware that the question of his speed was one of the major issues in this case, he very frankly accepted in his oral evidence that he had not looked at his speedometer before the accident and therefore that the speeds that had been given by him in evidence were only approximations.

- I shall deal first of all with the speed at which the Defendant's vehicle was travelling. In my judgment, the evidence in this case demonstrates, on the balance of probabilities, that the Defendant was travelling at a speed of 20 mph at the point of impact, and slightly more than this before impact. In relation to the expert evidence on this issue, I prefer the approach of Dr Searle to that of Mr Wade. I take into account Mr Levy's criticism of Dr Searle's evidence, in that (as Dr Searle frankly conceded) his initial report contained several errors. However, I nonetheless prefer his approach to that of Mr Wade, which also gave rise to a number of difficulties. I reach my conclusion for the following reasons:

- The Defendant's own evidence in his witness statement was that he was not travelling faster than 20 mph, although he felt it was around 15 mph. The Defendant's own view of his speed is however a matter of impression only, because he did not look at his speedometer. The various indicators of the speed of the Defendant's car contained in the expert evidence consistently give a speed closer to (or in some instances slightly above) 20 mph and not the 15 mph claimed by the Defendant in his oral evidence. I do not consider that the significance of the level of damage caused to this car in this accident (and in particular the issue of damage to the windscreen) merits the weight that is placed on it by Mr Wade. The evidence supports, in my judgment, a finding that the Defendant's speed at impact was 20 mph. Although Mr Wade raised a number of caveats and criticisms in relation to the statistical methods by which the Defendant's speed was calculated, I do not consider that this should lead to me rejecting the overall picture given by these various methods, taken with the Defendant's own evidence, of the Defendant's speed prior to the collision. Furthermore, notwithstanding the various criticisms which he made of the methods of calculating the speed of the Defendant's car, Mr Wade was still of the overall view that the Defendant's speed was in the range 15-20 mph. Finding that the Defendant was travelling at the top end of that range is not inconsistent with his evidence.

- The evidence about the Claimant's movements before the accident is scant. What is agreed between the parties about those movements is minimal. It is agreed that she was on a night out in York city centre. It is agreed that she departed from the southern kerb and that she was hit by the Defendant's car as it was travelling eastwards along the road. As I have already noted, none of the many other witnesses to this accident, including those who gave statements to the police, was called at trial by either side. I must make my determination based on the evidence given at trial:

- I therefore find, based on the evidence before me and applying the civil standard of proof, that the Claimant ran into the road from a standing start on the edge of the kerb at the southern side of the road. This is, I emphasise, not in and of itself a finding of any fault on the part of the Claimant. It is, rather, the finding of fact that I make about how the Claimant entered the carriageway and how she came to the point of collision.

- My finding of fact, based on the evidence given at trial, is that although the Claimant left the southern pavement from a standing start, she did so in order to run (rather than walk) across the road. I need then to consider how long the Claimant was in the road, having left the kerb on the southern pavement, before she reached the point of collision. As indicated above, the expert witnesses provided a helpful table of the times which, depending on various factors such as whether she was walking or running (and the speed of such a walk or run), the Claimant would have taken to travel from the southern pavement to the point of collision.

- I have found that the Claimant was running across the road. The experts differed in their approach to the speed at which a pedestrian such as the Claimant might be taken to run. A considerable amount of time was spent at the trial dealing with the merits of the Zebala Paper, used by Dr Searle, versus that of the Eubanks Paper, used by Mr Wade. The latter was right to observe, in his evidence, that all of this literature comes with limitations. I consider that, of these two, the Zebala Paper is the preferable measure of pedestrian speeds:

- As the authors of the Zebala Paper point out, however, when adopting a speed for the motion of a particular person, matters such as their state of health and their physical fitness should be taken into account. I do not have any evidence of the Claimant's state of health or physical fitness. Nor do I have any evidence about what she was wearing. It is far more difficult to ascertain with any degree of precision the speed of the Claimant's run across the road, as opposed to the speed of the Defendant's vehicle in the road. The speed at which the Claimant was running across the road is not ascertainable with any level of precision even on the basis of the figures in the Zebala Paper, which give a range of running speeds for the relevant age group of 2.0 metres per second (4.5 mph) to 3.6 metres per second, (8.1 mph) with a mid-point of 2.8 metres per second (6.3 mph)

- The experts were agreed that two other factors were of potential assistance in determining the Claimant's speed. These were the angle of the damage caused to the Defendant's vehicle (producing a ratio of their respective speeds) and the 'lateral throw' distance. They were agreed, however, that these calculations can only provide an approximate indication of relative speeds. I accept that these methods are indicative only, rather than a calculation of actual movement speed.

- Dr Searle's evidence was that calculating how long it took the Claimant to reach the point of impact was "the unreliable end" of the process, because it relied on a number of uncertain parameters. In my view there is some force in this point. It is not possible to ascertain the speed at which the Claimant was running across the road with any particular degree of precision. The calculations based on the evidence from the accident itself, i.e. the angle of damage to the car and the 'lateral throw', indicate an approximate speed at impact of about 5 mph (which is 2.2 metres per second). This is within the range for 'running' speeds of females of the Claimant's age given by the Zebala Paper, which the authors themselves recognise fall to be adjusted according to the particular characteristics of any individual.

- I find that the Claimant tried to cross the road by accelerating from a standing start to a 'running' speed of approximately 5 mph (i.e. around 2.2 metres per second) and that, based on the times given in the table at Section 13 of the Joint Statement, she was in the carriageway, after leaving the southern kerb, for a period of approximately three seconds prior to the collision occurring. I do not consider that the Defendant's evidence that the Claimant was running "fast" should lead me to reach a different conclusion: he had sight of the Claimant only for a brief moment before the collision, and I do not think that his impression of the speed at which the Claimant was running can be accorded great weight in those circumstances.

- On behalf of the Defendant, Mr Levy raised the question of whether the Claimant was intoxicated, as a result of her night out, prior to the collision occurring. I regard this point as far too speculative. There is a reference in the ambulance record to the Claimant having consumed alcohol, but there is no direct evidence of her having done so or, if she had done, in what amount. In Lunt v Khelifa, one of the cases upon which Mr Levy relied (see at [49] below), the evidence was that the pedestrian had consumed so much alcohol before the accident that blood tests conducted in hospital indicated that he had been three-and-a-half times the drink-drive limit (see at [6] of the Court of Appeal's judgment). There is no comparable evidence in this case and I do not regard the notes made by the ambulance crew as enabling a conclusion to be drawn, applying the civil standard of proof, that the Claimant was intoxicated at the time of the accident. It is therefore unnecessary to discuss any further the impact, if any, which that issue might have had.

- Having made that finding, I turn to the evidence about the situation of the Defendant.

- The Defendant's evidence was that he was aware from his long experience as a private hire driver in the City of York that pedestrians might enter the carriageway in this street. I accept the Defendant's evidence that he was keeping a lookout for pedestrians who might, as he put it, jump out in front of his car. That is supported by the fact that he referred in his witness statement to having seen someone running on the southern pavement (albeit towards the city centre and away from him) prior to the accident. It is clear, however, from the Defendant's evidence that the Defendant did not see the Claimant leave the southern pavement. Mr Levy relied on what the authors of the Zebala Paper said in this respect:

- I have accepted the Defendant's evidence that he saw the Claimant in the road prior to the collision occurring and that he depressed his brake pedal prior to impact in an attempt to avoid hitting her. I do not consider that Mr Wade's view that this was unlikely to have been the case should be accepted, in preference to the Defendant's own evidence on the point (which has been consistent throughout, since his police interview – that he saw the Claimant, then "hit the brakes" but was unable to avoid the subsequent collision). Mr Wade's view in any event depends on a number of factors about which there is, on any view, a significant degree of uncertainty, such as the Claimant's speed when running and exactly where the Claimant was in the road when the Defendant was alerted to her. The Defendant's evidence was that the Claimant was in front of his vehicle when he saw her; but she must have been somewhat to its offside, given the point of impact (which was to the offside of the Defendant's car) and the fact that the Defendant saw her running across his path before the collision occurred. There is, therefore, a distance over which the Defendant did not see the Claimant after she had left the southern kerb and after her motion had become recognisable as a potential hazard. To travel this distance at a running speed would have taken the Claimant approximately between one and two seconds, depending on the Claimant's precise speed, exactly where in the road she was when the Defendant saw her and the degree of acceleration which she had achieved from her stationary position on the southern kerb.

- Although the essential principles upon which this case must be decided were not really in dispute, I was referred to a number of authorities. In Barrow v Merrett, the Deputy Judge set out the position in the following terms:

- I was also referred to several appellate authorities dealing with the apportionment of liability in cases involving road traffic accidents between cars and pedestrians. I will set out the essential facts and reasoning in those cases, starting with Eagle v Chambers [2003] EWCA Civ 1107. In that case, the accident took place on a dual carriageway in a town centre at about 11:30 pm. The road was straight, the weather was fine and the street lighting was good. The claimant, then aged 17, was walking along the southbound carriageway. She had been doing so for some time and had been warned by bystanders and drivers to stop. She refused to do so. She had, the trial judge found, chosen to put herself in a dangerous position and rejected the warnings of those concerned for her safety. The claimant was struck by the defendant's car, which was travelling at about 30-35 mph, in the offside lane of the dual carriageway.

- The trial judge found that the defendant had fallen below the standard of care of a reasonable driver: he should have seen the claimant earlier and taken avoiding action. The road was straight, visibility was good and at least two other cars had been able to avoid her. Whilst the presence of the claimant in the offside lane was not to be expected, the defendant (whose driving abilities were impaired by drink) should have been able to see her, and take avoiding action, if keeping a proper lookout. Thus, negligence and causation were established. However, the judge concluded that the claimant ought to bear the greater share of responsibility for the accident and apportioned her share of the blame at 60 per cent. On appeal, the Court of Appeal (Ward, Waller and Hale LJJ) exactly reversed the trial judge's apportionment, reducing the claimant's liability from 60 per cent to 40 per cent. At [16], Hale LJ (giving the judgment of the Court) stated:

- In Lunt v Khelifa [2002] EWCA Civ 801, the Court of Appeal (Brooke and Latham LJJ and Hart J) upheld the trial judge's apportionment of liability, which was two-thirds to the respondent driver and one-third to the appellant pedestrian. The respondent had failed to see the appellant, who had walked into the road when the car was about 20-25 metres away, prior to impact and had not braked or taken evasive action. The appellant had, for his part, walked straight out in front of the respondent's car, having failed to see it. At [20], Latham LJ (with whose judgment Brooke LJ and Hart J agreed) held:

- In his concurring judgment, Brooke LJ said:

- In Stewart v Glaze, Coulson J dismissed the claim against the driver. The pedestrian, who was drunk, had been sitting at a bus stop, walked to the kerb and then ran into the road in front of the defendant's vehicle, which was travelling below the speed limit. The driver gave evidence that he was not focusing on the pedestrian but was looking at oncoming traffic ([74]). The judge found he had been driving carefully and that he had no reason to take any particular note of the pedestrian until after he had stepped off the kerb ([73]). The distance between the kerb and the point of impact was just 1.7 metres ([72]) and there was a period of only about one second between the pedestrian stepping off the kerb and being struck by the car ([77-78]).

- In Belka v Prosperini [2011] EWCA Civ 623, the trial judge held the appellant pedestrian was two-thirds to blame for the accident, and the respondent driver was one-third to blame. The appellant was using a pedestrian crossing point on a dual carriageway and, having crossed one side of the dual carriageway, had reached the central refuge. The judge found that the respondent should have seen the appellant when his car was 30 metres away from the point of collision. The appellant decided to run across the road, the trial judge finding that he deliberately took the risk of trying to cross in front of the defendant's car. The respondent only saw the appellant at the last moment. He braked and swerved but was unable to avoid a collision. The Court of Appeal (Rix, Hooper and Stanley Burnton LJJ) dismissed the appeal. At [12], Hooper LJ (with whose judgment the other members of the Court agreed) rejected the argument advanced by the appellant:

- In Jackson v Murray [2015] UKSC 5, [2015] 2 All ER 805, the pursuer (then aged 13) had stepped out from behind her school minibus into the path of the defender's car. The Lord Ordinary found that he had been driving too fast and that, having seen the minibus, he had made no allowance for the possibility that a child might attempt to cross in front of him. The Lord Ordinary reduced the pedestrian's damages by 90 per cent for contributory negligence, holding that the principal cause of the accident was her attempt to cross the road without taking proper care. On appeal, an Extra Division of the Inner House reduced the assessment of contributory negligence from 90 per cent to 70 per cent. On the pedestrian's further appeal, a majority of the Supreme Court further reduced it, this time to 50 per cent. Lord Reed gave the judgment for the majority. At [40-44], he stated:

- After I had reserved my judgment, my attention was drawn by the Defendant's Solicitor to the decision of Cavanagh J in Chan v Peters [2021] EWHC 2004 (QB), a judgment given on 16th July 2021. In that case, the claimant pedestrian was aged 17 and was hit by the defendant's car outside his school at lunchtime in circumstances of good visibility and weather conditions. The defendant was driving at 25 mph, well within the speed limit. The criticism of her driving was that she had failed to meet the standard of the reasonably competent driver in relation to her observation of potential hazards or the precautionary steps taken. The claimant had emerged into the road from between two parked vehicles (a car and a bus) on the defendant's nearside. He did not look before doing so; the defendant's view of the claimant was obscured because of the parked vehicles. The defendant saw the claimant when he emerged from between the parked vehicles, 0.6 seconds before the collision. She immediately slammed on the brakes but could not avoid a collision. The judge found (see at [94-96]) that the defendant was not, in these circumstances, negligent: she was travelling at an appropriate speed, was aware of her surroundings (including the parked vehicles), had not negligently failed to spot the claimant until he had emerged from behind the parked car and had then reacted reasonably by braking hard. It was suggested on behalf of the Defendant that this case contained a relevant consideration of avoidability calculations, which were agreed between the experts, although my attention was not directed to any particular passage. Cavanagh J stated at [90], having set out the bases of those calculations:

- In my judgment, liability is established in this case based on the speed at which the Defendant was travelling before the accident occurred.

- I have found that the Defendant's car was travelling at a speed of 20 mph at impact. In my judgment, in the particular circumstances (including the location of the accident, the large numbers of people and the history, known to the Defendant, of pedestrians jumping out into the road), a safe speed was no more than 15 mph. This was the speed that the Defendant himself accepted in his evidence was the safe speed. I have found that his evidence that he was in fact travelling at this speed – and not at the higher speed of 20 mph or (on the basis of some braking prior to impact) slightly more – is unreliable and I do not accept it. The Defendant was therefore travelling too fast in the particular circumstances.

- Notwithstanding the Defendant's own evidence on this issue, Mr Levy submitted that travelling at a speed of even 19 mph or 20 mph would not fall below the standard of a reasonable and prudent driver. I reject that submission. The Defendant's car was travelling through a city centre, late on a Saturday night, with large numbers of pedestrians on both sides of the road, many of whom would have come out of the surrounding pubs and bars. The Defendant was himself well aware of the possibility of pedestrians coming into the roadway, not taking care for their own safety. In those circumstances, in my judgment, the Defendant was correct to say that an appropriate speed having just crossed over the bridge at this time and in this location was no more than 15 mph. I also note that 15 mph was expressly pleaded in the Particulars of Claim as being the maximum safe speed in the circumstances, that the Defence consists of a bare denial of the relevant paragraph (although it transpired that the Defendant's own evidence at trial supported the Claimant's case on the point), and that neither party called any other evidence on the question of the maximum safe speed.

- I accept Dr Searle's evidence that if the Defendant had been travelling at a speed which was 80 per cent of his actual speed (and it may well have been a higher figure than even this, for the reasons given by Dr Searle in his evidence), then the Claimant having left the southern pavement as she did would have been able to pass across the road without colliding with the Defendant's vehicle. If the Defendant had been travelling at what he himself considered to be the safe speed of 15 mph (rather than at or slightly above 20 mph) then the accident would not have happened. As Mr Maskrey put it in his closing submissions, the reason that a lower speed avoids the collision is because if all other actions remain the same, the Claimant would have been able to run past the Defendant's car. In his oral evidence, Mr Wade sought to criticise this approach (although much of his criticism was not apparent from the Joint Statement), but I do not accept that it is not an appropriate one to apply in these circumstances where the issue is whether or not the Defendant was driving too fast. If the Defendant had been travelling at a lower speed of no more than 15 mph, as I have found he ought to have been doing, then this accident would not have happened. The Claimant's case is therefore made out on this basis, and primary liability in negligence established.

- Given that I have found primary liability has been established on the basis of the Defendant's speed alone, it is strictly unnecessary to deal with the Claimant's alternative case on liability based on the Defendant's failure to see the Claimant crossing the road earlier than he in fact did. Nonetheless, I ought to set out my view on this question.

- I have found that the person whom the Defendant saw running towards the city centre on the southern pavement before the accident was not, on the balance of probabilities, the Claimant. On that basis, the first point at which the Defendant saw the Claimant was when she was illuminated in his car's headlights in the carriageway. By this point, the Claimant had both left the kerb and travelled some distance across the carriageway. The first question is whether the Defendant was in breach of duty in failing to observe the Claimant sooner than he in fact did. Mr Maskrey submitted that the Defendant ought to have seen the Claimant leave the southern pavement, that he had failed to do so, and that he was negligent not to do so.

- As Mr Levy rightly submitted, the standard is that of a reasonable driver and the Court needs to be careful when considering a case where margins are slim, times are short, distances are short, speeds are not great and events happened over a very short compass of time. I have also had regard to what Coulson J said about the importance of the practical realities in a case such as this in Stewart v Glaze at [72-76], and at [82] to not elevating "what might have happened into an assumption of what should have happened".

- I have not found this an easy question to resolve, principally because this is a case in which the Claimant crossed the opposing lane before the collision occurred rather than coming from the Defendant's nearside. In my judgment, however, the Defendant's failure to see the Claimant attempting to cross the road until he did, just before the moment of impact when he saw her in his headlights, did not fall below the standard to be expected of a reasonable driver in these circumstances. The Defendant was well aware of the possibility of pedestrians coming into the road and was on his own account, which I accept, keeping a watch for this happening; indeed, he saw someone running on the southern pavement before the collision occurred. He was, therefore, taking care to ensure that an accident of this sort did not occur. I accept that the Defendant did not suggest in his evidence that immediately before the accident he was (for example) particularly focused on the northern side of the pavement – compare, on this issue, Stewart v Glaze at [74], where the driver's evidence was that he had been looking at oncoming traffic rather than the pedestrian. Nonetheless, the Defendant's evidence when cross-examined was that before the accident he was looking at what was happening on both sides of the road, and so not just at the southern pavement, from which the Claimant came. I reject Mr Maskrey's submission that what he described as the 'looking all over' argument lacks force because the nearside pavement had pedestrian railings and fewer people. There were still people on the nearside pavement, and the pedestrian railings ended at about the point of collision. There was, in my judgment, still a requirement to watch out for danger on both sides of the road in these circumstances.

- Nothing was obstructing the Defendant's view of the southern pavement and there were no vehicles coming towards him on the opposite side of the road. It was dark, although the road and both pavements were illuminated by street lighting. However, the Claimant ran into the road, in front of the Defendant's car, from a pavement that was crowded with pedestrians. I reject Mr Maskrey's submission that it was a breach of duty for the Defendant not to have seen the Claimant leave the offside pavement. She would not have been perceivable as a hazard until she had left the pavement and so emerged from the crowd; and I accept Mr Wade's view that it is only at the point when she was obviously crossing the road and not slowing that she might be considered as a hazard. Something that must also be taken into account in terms of her visibility as a hazard is the background from which she emerged, i.e. a crowd of other pedestrians.

- After accelerating from stationary, the Claimant would have been running in the road for a period of around two seconds before the collision. The Defendant did see her prior to impact and braked hard. Even on the Claimant's case, as put to Mr Wade in cross-examination, the Defendant would have had a further period of only between one and two seconds in which to see the Claimant running across the carriageway before he in fact saw her and braked. Whilst on this basis the Defendant would have had the additional 0.67 seconds necessary to stop his car before the point of collision had he seen the Claimant when (for example) she was in the middle of the offside lane and (at least at that point) perceivable as a hazard, the fact that the Defendant might have thereby avoided the accident does not mean that he fell below the standard of a reasonable driver in not avoiding the accident. I accept Mr Levy's submission that an allegation of negligent driving covering a period of this sort should, as it was in Stewart v Glaze (see at [83]), be described as "a fine consideration elicited in the leisure of the court room, perhaps with the liberal use of hindsight", particularly where the Defendant's evidence – which I accept – is that he was looking out for potential hazards coming from both sides of the road. In my judgment, he was taking reasonable care, in this respect, in the particular circumstances. I accept Mr Levy's submission, based on the authorities, that the Claimant's case here amounts to an elevation of the Defendant's duty from that of the 'reasonable' driver to that of the 'ideal' driver (see Stewart v Glaze at [82-83] and Ahanonu v SE London & Kent Bus Co. Ltd [2008] EWCA Civ 274 at [20] and [23]). The Defendant might have seen the Claimant sooner than he in fact did, but I do not consider that he fell below the standard of a reasonable driver in not doing so.

- It is therefore unnecessary for me to resolve the detail of the dispute between Dr Searle and Mr Wade as to the appropriate PRT (see [27(xi)], above). It is also unnecessary to deal with Mr Maskrey's submission that the Claimant would not have suffered the injuries that she did if the Defendant had been unable to stop his car prior to the collision but if he had been able to slow to a much lower speed of, for example, 2-3 mph. As Mr Levy submitted, this point was not explored in the evidence and it would have required a significant amount of additional evidence, including from medical experts.

- The ultimate conclusion that I have reached can be summarised in the following way. The Defendant was travelling at 20 mph, which although below the speed limit was too fast in the particular circumstances. If he had been travelling at a safe speed then the accident would not have occurred because the Claimant would have been able to cross the road before the Defendant's vehicle arrived at the point of impact. The Defendant was keeping a lookout for danger, including for pedestrians who might enter the road from the pavements on both sides, but failed to see the Claimant running across the road until it was too late for him to stop in time. In the circumstances of this case, I do not find that the Defendant's failure to see the Claimant sooner than he did fell below the standard of a reasonable driver.

- I now turn to the final question, which is what deduction should be made for contributory negligence. On behalf of the Claimant, Mr Maskrey accepted that there should be a deduction because the Claimant did not look when entering the road. This was a concession which was, in my judgment, correctly made. All the evidence is that the Defendant's car was there to be seen. The Claimant made a serious error in attempting to run across the road without looking first.

- Mr Maskrey submitted that the appropriate deduction for contributory negligence in these circumstances was one of between 25 and 40 per cent. He resisted any greater reduction than that. He relied on the Court of Appeal's decision in Eagle v Chambers, which I have summarised above. For his part, Mr Levy also relied on Eagle v Chambers, submitting that the present case was just the situation identified by Hale LJ of a pedestrian suddenly moving into the path of an oncoming vehicle in which the greater share of liability ought to fall on the pedestrian rather than the driver. But, as Mr Maskrey pointed out, this was not a 'sudden' event in the sense that it was not one expected by the Defendant: what happened was precisely what the Defendant feared might happen.

- As to the overall apportionment of liability as between the parties in this case, the following appear to me to be the significant points, taking account of the causative potency and blameworthiness of both parties:

- There will therefore be judgment for the Claimant for damages to be assessed, subject to a deduction of 50 per cent for contributory negligence.

Deputy Judge Mathew Gullick QC:

Introduction

"7. Before turning to the substance of the judgment I set a general observation about the evidential difficulties faced by Courts and litigants in civil proceedings which revolve around the reconstruction of fast moving and traumatic events such as this road traffic accident.

8. There are many claims arising out of accidents, be they on the road, in the home or in the workplace, in which it is simply not possible to conclude with absolute precision what occurred. The law does not require the Court to do so. The task for the Court is not to reach a conclusion based on 'certainty' as to what occurred but rather to come to a reasoned view as to the most probable explanation. In many accidents there will be a range of confounding factors which render the task of precise reconstruction of events impossible. This case exemplifies many of these factors. The trial concerns an event that from beginning to end lasted no more than a few seconds. It was not recorded on CCTV or a 'dashcam' and the few eye-witnesses to the collision all viewed events from different positions in the road and pavement. There was little 'hard evidence' such as extensive damage to the car that would enable ready reconstruction. [The Claimant's] physical injuries in themselves do not provide clear answers to the core questions, nor (as explained later) does the evidence from the accident reconstruction experts.

9. A Court attempts to reconstruct the most probable answers to the core questions by applying established forensic tools to such evidence as is available. It looks at the evidence in its totality, it seeks to understand the relevant layout of the scene, identify any objective facts that might act as lodestars by which more subjective opinion and recollection can be tested, scrutinises carefully the accounts of witnesses of fact and experts, both in the witness box and in earlier written statements – and it applies to all of this a fair dose of common sense.

10. All of this will strike those well used to litigation as a statement of the obvious. It is nevertheless important to spell out the evidential task, and the legal standard applied, so that others, not least the parties themselves, can well understand the basis on which I have proceeded to analyse this case."

Background to the Accident

Circumstances of the Accident: the Defendant's Evidence

Circumstances of the Accident: Expert Evidence

i) Section 10: The Claimant's speed, at least at the moment of impact, appeared to have been slow, i.e. only walking pace. Dr Searle reached this conclusion because of the diagonal direction of the marks on the vehicle's bonnet, the small lateral distance over which the Claimant had travelled before coming to rest on the road, and that the Claimant had kept her orientation after the accident rather than turning or tumbling.

ii) Section 12: The Claimant, unaware of the Defendant's approaching vehicle, attempted to walk across the road and on becoming aware of the situation had turned to face the car. If walking to the point of impact from a standing start, a distance of 6.4 metres, the Claimant would have taken between 4.9 and 7.3 seconds. If running, the time would be 3.1 to 4.5 seconds.

iii) Section 13: The collision could have been avoided if the Claimant had looked to her left before starting to cross the road. After the impact, the car had taken a similar distance to stop to that taken by the Claimant, suggesting that the brakes had already been applied when the impact occurred, but that the car had not stopped at the time of impact. Whether the Claimant was walking or running, there would have been sufficient opportunity for the Defendant to stop if he had seen the Claimant leaving the kerb, even if he had been travelling as fast as 30 mph.

i) Section 5.1: The damage to the Defendant's car was modest, consistent with a low speed impact of approximately 15-20 mph. There was a small dent to the offside bonnet, cracking to the offside of the front registration plate, and marks on the bonnet and the nearside windscreen. However, the windscreen was not broken or cracked. Even at low speeds (17 mph), a study of tests using dummies had demonstrated that a windscreen would fracture through contact with the dummy's head ("Vehicle damages and longitudinal throwing distances when using biofidelic dummies in comparison to conventional dummies" by Kortmann & Hoger – which I shall refer to as "the Kortmann Paper"). The angle of the 'line' of the damage on the Defendant's vehicle was approximately 30 degrees, relative to the centreline of the car. If the speed of the car was 15-20 mph then this would suggest that the Claimant's speed was about 9-11 mph (i.e. about 3.9 to 5.2 metres per second), which is consistent with her running rather than walking at the moment of collision. Had the Claimant been walking then the pattern of damage would be much more closely aligned with the centre of the Defendant's vehicle.

ii) Section 5.2: The point of collision was approximately 5.2 metres from the southern pavement and 2.0 metres from the northern pavement.

iii) Section 5.3: Using 50th percentile speeds reported in academic literature for 'jogging' (which Mr Wade considered would approximate more to running across a road, as opposed to speeds given for 'sprinting'), it would have taken the Claimant approximately 1.5 seconds to travel from the southern footway to the point of collision. At the 85th percentile speed this would have reduced to 1.2 seconds. These times would be slightly longer if the Claimant had been stationary at the kerb. The paper used by Mr Wade was "Pedestrian Speeds" by Jerry Eubanks, a collision reconstruction expert based in California, published in 1998. I shall refer to it as "the Eubanks Paper".

iv) Section 5.4: Using mathematical formulae based upon the distance that the Claimant travelled after being projected off the front of the car (the 'throw distance'), Mr Wade calculated the speed of the vehicle as likely being around 22 mph (within a range of 17 mph to 27 mph). Calculations based on the car's stopping distance also suggested speeds somewhat in excess of 20 mph, although they were dependent on precisely how far the vehicle had been reversed after coming to a stop (which was unknown) and also on assuming full braking from the point of collision to the car coming to a stop. Mr Wade considered these calculations to be illustrative only. He did not consider that speeds in excess of 20 mph were consistent with the damage to the car.

v) Section 5.5: There was street lighting installed at the scene of the accident and additional light would have been cast from lighting from the premises along both sides of the road. Police photographs and CCTV show that there would have been sufficient ambient light for a pedestrian to be seen in the carriageway. The Claimant would have had a clear view of the Defendant's vehicle when she entered the carriageway. The headlights of the approaching car would have been clearly visible.

vi) Section 5.6: If the Claimant was running when crossing the road (i.e. using the 'jogging' speeds in the academic literature relied on by Mr Wade), then the collision was unavoidable; the car might have slowed down by as much as 9 mph prior to the collision, but only then if the Defendant had a 'Perception Response Time' ("PRT") at the lower end of the range, had detected the Claimant when she left the kerb, and had achieved full emergency braking after the minimum brake build-up time.

i) Section 2: A pedestrian making the crossing from the southern to northern pavements would need to give some clearance to the pedestrian railings on the northern side. A laser scan of the scene as the police found it showed the front of the Defendant's car at 6.2 metres past the railings and blood from the Claimant's head injury at 8.0 metres past the railings. The Defendant had said that he had reversed about a foot (0.3 metres) after the collision, so the initial rest position of his car was taken to be 6.5 metres past the end of the railings. The Claimant's centre of gravity, based on the position of the blood, would have been 7.4 metres from the end of the railings.

ii) Section 3: The collision point appeared likely to be located about 0.5 metres to the east of the pedestrian railings. The dent on the front of the Defendant's car appeared to have been made by the Claimant's hip and was 0.2 metres to the offside of the vehicle's centreline. On the police scan, the vehicle's centreline was 5.6 metres from the offside kerb (from which the Claimant had travelled). The point of collision was therefore 5.4 metres from the offside kerb.

iii) Section 5: The 'throw distance' of the Claimant's centre of gravity was approximately 6.9 metres. The Defendant's car had come to rest about 6.0 metres beyond the point of impact.

iv) Section 6: The experts differed slightly on the distance which the Claimant would have travelled. Dr Searle considered that a pedestrian standing with their toes at the kerb edge would have their hip 0.2 metres further back, which would make the distance of travel to the point of impact 5.6 metres. Mr Wade considered that the position of the Claimant's hip was uncertain and so used the distance from the kerb edge of 5.4 metres.

v) Section 7: In addition to the impact with the Claimant's hip, damage lower on the Defendant's car appeared to have been made by the Claimant's legs. She had then gone onto the bonnet, making further damage marks. One of those had been recorded by the police and was linear in form. It appeared to have been made by a harder object such as a button, buckle or stud. Mr Wade considered it might also have been made by a watch or jewellery on an outstretched hand. There were a couple of minor dents on the nearside of the linear mark, and a scratch on the rear edge of the bonnet. The Claimant's head and possibly upper body appeared to have contacted the lower part of the windscreen.

vi) Section 8: The experts agreed that there were three potential indicators of the speed of the vehicle at impact. These were: the 'throw distance' of the pedestrian, the braking distance of the vehicle, and the level of damage. Of these, interpretation of damage was more subjective than the other two methods. As to the interpretation of the damage:

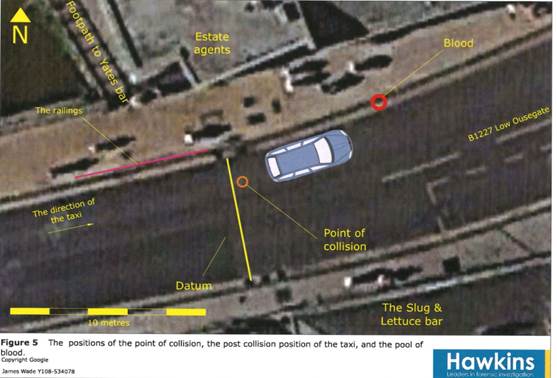

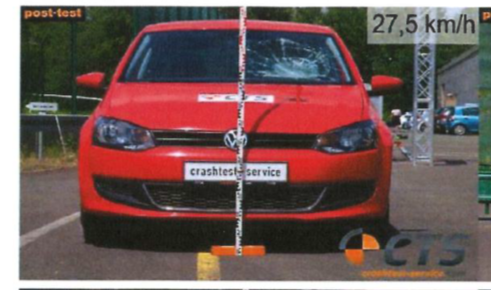

a) Dr Searle considered that the study relied on by Mr Wade in support of his view on the damage, which involved staged collisions using dummies, was unhelpful because the staged collisions were made with larger dummies and using smaller cars than involved in this accident. When allowing for the relative sizes of the pedestrian and car in the present case, a speed of 20 mph or more was supported even without the windscreen having cracked. Mr Wade considered that the tests were relevant, and that although the dummies used in the tests were likely taller and heavier than the Claimant the differences in the sizes of the dummies and vehicles used in the tests did not undermine their relevance in considering the profile of the damage caused in this collision when compared with the test collisions. Mr Wade's opinion, based on the damage, was that the speed of the car was between about 15-20 mph, but likely no higher than 20 mph. Image 4 in this Appendix to this Judgment shows the damage to a VW Polo car used in the tests described in the Kortmann Paper, relied on by Mr Wade.

b) The experts disagreed about the angle of the progression of the damage across the bonnet of the car. Dr Searle considered that the linear mark was of significance because it was a prolonged contact from something either on, or trapped beneath, the Claimant's body. He considered it was not consistent with e.g. an object such as a watch or a ring on an outstretched hand, because such items would simply bounce off. The angle of the linear mark gave a ratio of 1 in 4, which was the best way of determining the ratio of the speeds of the car and of the Claimant. Mr Wade disagreed with these conclusions of Dr Searle, considering that it was unsafe to consider only the angle of the linear mark as its cause was unknown. When considering all the damage to the vehicle, the angle of damage was closer to 26 degrees, giving a ratio of 1 in 2. Image 5 in the Appendix to this Judgment is a diagram prepared by Mr Wade indicating the approximate positions of the damage to the Defendant's car and plots the angles across the car.

vii) Section 9: The experts agreed that 'lateral throw' did not indicate what the speed of either the Claimant or of the Defendant's car was in isolation, but that it did provide an indication of the ratio of their respective speeds.

a) Dr Searle considered the Claimant had continued laterally after impact by more than a metre (although less than the 1.9 metres suggested by Mr Wade), whilst travelling over 7 metres longitudinally. That ratio would indicate that she had been travelling at about one-fifth of the speed of the Defendant's car (i.e. 4 mph if the Defendant's car had been travelling at 20 mph). Even if the 'lateral throw' had been reduced due to the Claimant hitting the kerb, the ratio would be no more than one in four.

b) Mr Wade considered that calculations based on 'lateral throw' were skewed by the Claimant having struck the northern pavement, the collision occurring at a relatively low speed and that the Claimant had first contacted the offside centre of the Defendant's vehicle, which was curved and would have reduced her lateral speed across the width of the car. He considered this was the least accurate method of considering pedestrian movement speed. His view was that the 'lateral throw' should be calculated as the distance from the dent on the offside of the bonnet to the blood found on the road, which was 1.9 metres. This would suggest a speed for the Claimant of between 4 and 5.4 mph.

viii) Section 10: The experts relied on different research as to the speeds normally represented by walking or running:

a) Dr Searle relied on the study "Pedestrian Speeds and Acceleration", conducted by Jakub Zebala, Piotr Ciepka and Adam Reza of the Institute of Forensic Research in Krakow, Poland, published in 2013 (which I shall call "the Zebala Paper"). They conducted a time-distance analysis of test subjects crossing roads at the subjects' own interpretation of the speeds 'slow walk', 'ordinary walk', 'fast walk', 'running' and 'sprinting'. Each subject was observed covering the measurement distance three times in each manner. For females aged 21-30, the range of speeds observed for 'running' was between 2.0 metres per second and 3.6 metres per second. These were somewhat lower than the speeds that had been observed in two earlier studies, one of which (Strouhal, Kuhnel & Hein) gave a range for 'running' speeds of females in this age group of 2.7 metres per second to 3.6 metres per second, and the other (Eberhardt & Himbert) a figure of 4.0 metres per second. The sample size of the Zebala study was relatively small – 26 females and 28 males across all age groups. Nine of the females were in the 21-30 age group.

b) Mr Wade relied on the data given in one of the tables in the Eubanks Paper. Mr Eubanks had, for the purposes of the data in this particular table, had 541 'joggers' observed in a beach area. The ages of the joggers were estimated by the observers. 52 female joggers were placed in the 20-30 age group. The speed for the 15th percentile of this group was 2.8 metres per second, for the 50th percentile it was 3.5 metres per second and for the 85th percentile it was 4.2 metres per second.

c) The experts were agreed that if the Claimant had started to cross the road from a stationary position, that would add to the time taken to reach the point of impact. They agreed that the Zebala Paper showed that starting from stationary added about 0.4 to 0.8 seconds to the time needed to reach the point of impact, with a median of 0.6 seconds.

ix) Section 11: The experts prepared a table setting out calculations of the time which the Claimant would have taken to reach the point of collision from the southern pavement, based on their respective travel distances of 5.4 and 5.6 metres, calculated both from a standing start and at a constant speed. Calculations were given on three bases: [a] using the angle of damage to the Defendant's car; [b] using the 'lateral throw' distance (both based on assumed speeds of the Defendant's car of 15 and 20 mph) and [c] based on the speeds given for walking and running in the studies upon which the experts had relied. The times given in this table for the Claimant to travel from the southern pavement to the point of collision vary from as little as 1.5 seconds to as much as 6.4 seconds, depending on the method of calculation used and the constants (such as the crossing distance and the speed of the Defendant's vehicle) that are assumed for the purposes of the particular calculation.

x) Section 12:

a) The experts recorded that they were largely in agreement about the speed of the Defendant's vehicle normally represented by the distance over which the Claimant was projected forwards in the accident. Two commonly used formulations by accident investigators, in use by the police and recommended by the Home Office, resulted in a median value of 19.4 mph (Searle and Searle) and a median value of 21.0 mph (Smith and Evans). Mr Wade's view was that the formulae would likely lead to an overestimate of the speed of the Defendant's car as it was likely that the collision had occurred before the Defendant's PRT had elapsed and so the car was likely not being braked at impact.

b) Dr Searle calculated that based on the braking distance of the Defendant's car, using the lowest braking rate measured by the police when testing the vehicle, that at 15 mph the car would stop in just over 3 metres. Even on the lowest recorded braking rate the 6 metres braking distance after impact represented a speed of 20.7 mph at impact. Mr Wade agreed with Dr Searle's calculations but considered that information about the precise nature of the skid tests conducted by the police was limited – e.g. whether the Defendant's own vehicle was in fact used, whether the test was conducted with ABS enabled or disabled, or from what speeds the braking tests were performed. He considered that given the usual nature of such police tests, which in his experience were conducted by trained police drivers applying maximum braking effort at 30-40 mph, attempting to apply the maximum recorded deceleration over a very short distance and from a low speed would give shorter distances than in reality and be misleading.

c) Dr Searle's overall view was that the speed of the Defendant's vehicle at impact was 20 mph or perhaps a little more. Mr Wade's opinion was that the level of damage to the car, particularly the unbroken windscreen, was not consistent with a speed higher than 20 mph. Mr Wade considered that the 'throw' distance and braking distance calculations provided overestimates because the car was likely either not braked before impact, or full braking deceleration did not commence until after impact. His view was that the speed of the car at impact was likely in the range 15-20 mph.

xi) Section 13: The experts disagreed about the time over which the Defendant could have responded to a hazard:

a) Dr Searle considered that PRT and 'brake lag' were different and consecutive periods. PRT was composed of the time to perceive the hazard, the time to decide to brake in response, and the time to transfer the foot to the brake pedal. 'Brake lag' was made up of 'dwell' by a driver on the brake pedal before starting to press it, and the effect of the short but finite term taken to build up the force applied. In the case of the Defendant, 'dwell' was irrelevant because of his evidence that he had "hit the brakes", i.e. landing his foot on the brake pedal and applying pressure in a single movement. Dr Searle had increased the PRT time to take into account the period for maximum braking. Dr Searle considered that reliance on the paper by Greibe, used by Mr Wade, would greatly overestimate the extent of brake lag for a professional driver (such as the Defendant, who had been a professional driver his entire working life). Relying on research by Martin & Holding, Dr Searle considered that the PRT should be extended by either 0.175 seconds or 0.075 seconds to reflect the time to maximum brake pressure. Mr Wade considered this methodology to be incorrect, and that PRT and 'brake lag' should be added together.

b) The experts were agreed that the Defendant would have had a reaction time between seeing the Claimant in the road and responding to her as a hazard. Research by Olson reported a median PRT of 1.1 seconds for unalerted drivers who, without warning, encountered an obstacle. The PRT for an 'alerted' driver (who expected to encounter an obstacle but did not know when) would be 0.4 seconds faster.

xii) Section 14: The experts were agreed that if the Defendant had not seen the Claimant until well into her crossing, or if he had been slow to apply the brakes, there would have been little opportunity for speed loss before impact. However the duration of braking was unknown because it was not known where the Claimant was first seen in the course of her crossing. If the Claimant had been sighted very late, then there would have been little time for loss of speed before impact, even if the Claimant had been walking.

xiii) Section 15: The experts agreed that how far the Defendant's car was from the point of collision when the Claimant began to cross was also subject to uncertainty. This would depend on the car's travelling speed, the duration of the Claimant's crossing and the extent of any pre-impact braking.

xiv) Section 16: The experts here dealt with avoidability.

a) The experts agreed that if the Claimant had been walking across the road and had been detected by the Defendant at the moment she left the kerb, the Defendant would have been able to stop from any speed within the 30 mph limit.

b) The experts agreed that given the overall distance the Claimant had to travel to reach the opposing kerb (7.3 metres), if the Defendant's car had been travelling at 74 per cent of its actual speed she would have reached the kerb before it arrived, if the Defendant's car was at the same point in the road when she began her crossing and not reducing speed. So if the Defendant's car had been approaching at 20 mph, a speed of 15 mph would have allowed the Claimant to cross the road. If the Defendant had been able to brake and reduce speed, the Claimant would have reached the far kerb if he had been travelling at a slightly greater percentage of his actual speed.

c) The experts also agreed that if the Defendant had been travelling at a slower speed which resulted in a stopping distance of 6.0 metres less, the collision would have been avoided because the Defendant would have braked in time, again assuming that the situation was otherwise the same as in the accident. The slower speed required to stop in time would depend on the actual speed of travel, the Defendant's PRT and 'brake lag', on which the experts differed. Dr Searle considered that if the Claimant had been travelling at 20 mph, a speed of 14 mph would have enabled him to brake in time; at 15 mph, the speed needed to brake in time would be 8 mph. Mr Wade considered that the relevant speeds were 13.8 mph (for an actual speed of 20 mph) and 9.2 mph (for an actual speed of 15 mph).

d) The experts agreed that if the Defendant had seen the Claimant as a hazard slightly earlier and so started his braking 6 metres before he did, the collision would have been avoided. Dr Searle considered that for an approach speed of 20 mph, this would be achieved by braking 0.67 seconds earlier, and that the Defendant would have gained that time had he seen the entirety of the crossing; the Zebala Paper showed that a pedestrian setting out to run would take 0.8 seconds to accelerate to the speed of a fast walk, so that if the Claimant was running when first seen by the Defendant then he missed the first 0.8 seconds of her journey. If the Defendant had seen the Claimant on the kerb before she started to cross then his response would have been an additional 0.4 seconds faster (as an 'alerted driver') and braking would have started 1.2 seconds before it actually did. Mr Wade considered however that this was unrealistic because it was based on a driver undertaking an emergency response to a pedestrian on the far side of the road, which would make driving in urban areas impossible.

e) Dr Searle's overall opinion was that the Defendant's speed at impact was 20 mph, and the Claimant's speed at impact was about a quarter of that figure, i.e. 5 mph. With a slightly slower approach speed, or a slightly earlier response by the Defendant, there would have been no collision.

f) Mr Wade's overall opinion was that the speed of the car at impact was in the range 15-20 mph, that the Claimant was running when the accident occurred, and that based on the likely crossing time and the typical driver PRT, depending on when they first detected the pedestrian a driver would have little to no opportunity to brake and slow the car before the collision. Mr Wade agreed with the mathematics of Dr Searle's avoidability calculations, but did not consider them particularly relevant because they depended on a judgment by the Court of what the appropriate speed for the conditions was and when it would have been realistic for a driver to have first detected the Claimant as a hazard.

i) Dr Searle said that there were three factors that would increase the percentage of its actual speed at which the Defendant's car would have had to travel in order to avoid the collision from 74 per cent to a higher figure. These were: the amount of braking before impact; if the Claimant had accelerated to a running speed from a standing start (because the calculation of 74 per cent assumed a constant running speed throughout) and calculating the figure on the basis of the Claimant clearing the Defendant's car rather than reaching the kerb (because there would have been a gap between the nearside of the car and the kerb). The latter issue on its own would increase the percentage from 74 per cent to about 80 per cent.

ii) Dr Searle accepted that several aspects of his initial report were incorrect, including the distance that the Claimant had travelled to the point of impact and also that the Claimant was not walking. The times that Dr Searle had given in his initial report for the Claimant travelling to the point of impact were incorrect. Dr Searle said he had benefited from his discussion with Mr Wade.

iii) In the cross-examination of Dr Searle and subsequently in Mr Wade's evidence-in-chief, it was suggested that if the Defendant had achieved maximum deceleration then there would be some indication on the road or the tyres of this having happened. Dr Searle rejected this proposition, noting that it had not been raised with him by Mr Wade. His evidence was that this might have been the case in the early days of anti-lock braking systems, but not in the case of modern cars.

iv) The report of the police accident investigator demonstrated that the police skid tests had been performed in the Defendant's car with the anti-lock braking system enabled, as it had been at the time of collision (see [27(x)(b)], above).

v) Mr Wade accepted that if the Defendant's evidence was correct that he had braked at or before the point of collision, then if travelling at 20 mph he would have avoided the collision by braking 0.67 seconds earlier than he in fact did (and for a speed of 15 mph, 0.89 seconds earlier), and that there was enough time for the Defendant to have brought his car to a halt if he had concluded the Claimant was a hazard as she left the kerb or even if he had first seen her in the centre of the offside lane. Mr Wade however cast doubt on the correctness of the Defendant's evidence that he had braked before the collision occurred, considering that he could only have braked after the impact and therefore that he was travelling at the point of impact at a speed below 20 mph.

vi) Mr Wade also sought in his oral evidence to question the value of the 'avoidability' calculations set out in the Joint Statement, although he did not dispute their mathematical correctness.

Findings of Fact

The Defendant's Speed

i) The speed limit was 30 mph. The Defendant's evidence, which I accept, was that he was travelling at a significantly lower speed than that immediately prior to the accident, because of the danger that might arise from the many pedestrians on the northern and southern pavements and because of the layout of the road (including the presence of traffic signals and the impending sharp right turn which he would have made shortly after the accident occurred). Thus it is improbable that the Defendant was travelling at a speed close to the 30 mph limit; the evidence does not support that.

ii) Although the Defendant said in his police interview, very shortly after the accident, that he was not travelling "fast" prior to the accident, he did not give an indication of his exact speed, or (for example) positively assert that he had been, or believed that he was, travelling at only 15 mph.