Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

England and Wales High Court (Queen's Bench Division) Decisions

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> England and Wales High Court (Queen's Bench Division) Decisions >> O'Connor v Luton Borough Council [2021] EWHC 1691 (QB) (22 June 2021)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/QB/2021/1691.html

Cite as: [2021] EWHC 1691 (QB)

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

QUEEN'S BENCH DIVISION

Strand, London, WC2A 2LL |

||

B e f o r e :

____________________

| LOUISE O'CONNOR |

Claimant |

|

| - and - |

||

| LUTON BOROUGH COUNCIL |

Defendant |

____________________

MR IAN CLARKE (instructed by DAC Beachcroft Claims Ltd) for the Defendant

Hearing dates: 24, 25, 26 and 27 May 2021

____________________

Crown Copyright ©

- By this action, the Claimant claims damages for injuries sustained when her motorbike collided with a car in Leagrave High Street on 13 September 2016. The claim is against the Highways Authority, it being alleged that the Claimant lost control of the motorcycle as she was leaving a petrol station as a result of the dangerous condition of the road and it was this that caused her to collide with the motorcar.

- By order of Master Thornett of 13 May 2020, the issue of liability has been tried as a preliminary issue.

- Evidence was heard from a number of lay witnesses including the Claimant herself. I also heard expert evidence from expert collision investigators, experts on the handling of motorcycles and highways experts.

- The Claimant, Louise O'Connor, was born on 5 April 1969. She passed her driving test for motorcars at the age of 17 and in about 2010, she took up motorcycling. She took and passed the compulsory basic training (CBT) which is the course usually taken before someone is allowed to ride a moped or motorcycle on the road. This then allowed her to ride a motorcycle up to 125cc. She then undertook the two modules leading to her passing her full motorcycle test on 16 May 2012 which, as she was over 24 years of age, allowed her to ride any motorbike.

- The Claimant describes herself as a "hobby motorcyclist", riding at summer weekends and perhaps a couple of times a month, along with Tuesday runs with a motorcycle club. In about October 2015 she bought a Ducati 800cc scrambler from new. Despite its name this is not a "dirt-bike" but a light, traditional "sit up and beg" machine, popular amongst female riders due its light weight and low seat height. She had previously owned a Ducati Monster motorbike. By the time of the accident, the Claimant had reach 600 miles on the Ducati scrambler which perhaps indicates its very occasional usage.

- Two members of her motorcycle club gave evidence and they described the Claimant as significantly less experienced than other riders. Thus, Mr Antony Smith stated:

- On Tuesday 13 September 2016, the Claimant made arrangements to attend her motorcycle club. She had not used the motorbike for over two weeks and she discovered it was low on fuel. The arrangement was that the members of the club would travel in convoy to the club premises. The Claimant asked her son, Carter, to text the other riders and let them know that she was intending to fuel up at the Jet garage on Leagrave High Street. This was not her garage of choice as Ducati recommend Shell V Power petrol and she said she would only use the Jet garage occasionally such as on this occasion when she would be meeting the others on the same route. She had previously filled up her car there, but never her motorcycle and it was her first visit to that garage on the Ducati.

- The arrangement was that, after filling up, she would join the other three riders who were travelling together that evening, as they passed the Jet garage. The Claimant was the least experienced rider and she would therefore travel second in the convoy. The time was about 8pm. After filling-up and paying, she got on the bike and heard the other bikes riding down the road (on the same side as the Jet garage). The first of the other motorcyclists was known as "Minty". He was followed by Mr Smith and then Mr Toombs. As they rode down Leagrave High Street, they saw the Claimant waiting on the garage forecourt, ready to pull out. Mr Smith therefore slowed down so as to create a gap for the Claimant to pull into, behind Minty and ahead of Mr Smith. As Minty rode past, he nodded at the Claimant and she nodded back indicating that she was ready to pull out and join them. Mr Toombs, at the back, was riding towards the centre of the road to prevent any cars from overtaking them and moving into the gap between the front two motorcycles.

- What then happened is described by Mr Smith in his witness statement as follows:

- The car with which the Claimant collided was being driven by Ms Kelly Tunnicliffe and was a silver coloured Chrysler Grand Voyager motorcar. Ms Tunnicliffe had four children in the car with her aged 7, 9, 11 and 15 years and, needless to say, she was entirely blameless in this accident. She had just crossed a mini-roundabout and was driving only at 10-15 mph, she thought. She was aware of the Claimant emerging from the exit of the petrol station. She described what happened as follows:

- Ms Tunnicliffe was being followed by Ms Ruth Gendi in a Skoda Fabia motorcar. She says she was keeping a safe distance behind the Chrysler and was about 40 metres away from the Jet garage when she first saw the motorcycle. Her attention was drawn to it as it was "behaving in an unexpected way". She says:

- Finally, Mr Toombs stated in his statement:

- In the traffic following Mrs Tunnicliffe and Ms Gendi there happened to be two police officers, Detective Sergeant Clare Gilbert and PC Daniel O'Mahoney. They immediately took control of the situation. Mr Smith, who is trained in first aid, was attending to the Claimant, and he gave appropriate first aid until the ambulance personnel arrived. There happened also to be a marked ambulance travelling along Leagrave High Street which was stuck in the queue of traffic approaching the mini-roundabout. The ambulance crew got out and ran to the scene of the accident and took over from Mr Smith attending to the Claimant. They were joined by other paramedics and they, together with DS Gilbert, treated the Claimant. Eventually, when it was safe for the Claimant to be moved she was conveyed to the nearby Luton and Dunstable Hospital. The Claimant's injuries were initially feared to be life-threatening: she had bleeding to her brain as well as a severely broken right arm, broken left arm, broken left leg and collapsed lung. One of the consequences of the head injury is that the Claimant herself has no recollection of the accident at all.

- PC O'Mahoney had commenced a collision report book which he had with him and he started to record the details of those involved and to take brief initial statements. He describes what he told by Ms Tunnicliffe:

- PC O'Mahoney also stated that, during his conversations with various people at the scene, he vaguely recalled a suggestion that the Claimant had slipped on something as she exited the petrol station but he could not recall who had suggested this. The suggestion was that the rider had slid on grease or diesel or petrol spillage. As it turned out, there was no substance to this suggestion at all and it seems to me that it may have been mere conjecture on the part of someone trying to reason in their mind how the accident could have happened. PC O'Mahoney also says:

- Given the seriousness of the injuries to the Claimant, the investigation was escalated to the Roads Policing Unit and PC Jenkin arrived on the scene at 21:49 hours. When he heard the suggestion of a possible diesel spillage having caused the Claimant to lose control of the motorbike, he, together with PC Hollingsworth, carried out an inspection of the forecourt of the garage to see if there were any contaminants that could have caused the incident. He did not see any spillage or any contaminant on the surface that would support the theory that the Claimant had skidded on something. In his statement, PC Jenkin said:

- When the police were informed by the hospital that the Claimant's injuries were now considered to be more serious than initially had been thought, and were potentially life threatening, the investigation was further escalated up to the Forensic Collision Investigation Unit and members of that unit, including Police Sergeant Cordingley and PC Hollingsworth attended that night. PS Cordingley directed the FCIU to carry out a full investigation and he stated:

- PC Hollingsworth is a Forensic Collision Investigator and when he arrived at the scene he was told by PS Cordingley that the Ducati motorcycle rider was coming out of the petrol station forecourt and that she lifted the front wheel of the bike which caused her to lose control and go across the road into the Voyager coming the other way. I should comment that there is no substance whatsoever in the suggestion that the claimant deliberately lifted her front wheel: the front wheel did come up, and it may have appeared that way, but as I explain later in this judgment, it was in fact entirely involuntary on the part of the Claimant. PC Hollingsworth carried out a visual inspection of the road surface from the petrol station forecourt across the carriageway together with PC Jenkin and found that the carriageway surface was good and there was no contamination visible. He examined the vehicles involved, he took photographs and he carried out a 3D laser scanning survey of the scene. He considered that the Chrysler Voyager had rolled on one car length from the point of impact and that the driver had steered left towards the kerb and away from the bike. The wheel angle of the Chrysler showed a left steer and by tracking back along the tyre line he found that the bike was on this line. He concluded that the Ducati had therefore hit the Chrysler and had dropped on its side and stopped rather than sliding on. For the purposes of his statement he was asked if he was aware of any holes or depressions in the road surface at the edge of the carriageway which might have been a contributory factor. He stated:

- Returning to the evidence of Kelly Tunnicliffe, contrary to what was said by PC Hollingsworth, she was sure that she was stationary when the motorcycle hit her car. She confirmed that she was watching the motorcycle the whole time, she was not going very fast and that she braked and steered towards the kerb. She said:

- Finally, I should refer again to the evidence of Mr Toombs. He said that once the Claimant had been taken away in the ambulance, he, Mr Smith and Minty walked back to the garage. He then said this:

- On 26 September 2016, the Claimant's daughter and son sent to the Highway Services Department of the Defendant an email in the following terms:

- The following day, 27 September 2016, a Highways Inspector, Peter Gell, visited the site and raised an order for repair. Repairs were carried out the same day. The requisition for the work (at page 393 of the bundle), raised by Mr Gell, required the contractor to "make safe potholes" with a priority time of one hour. A temporary repair using a cold mix bituminous proprietary product called Instamac was carried out. Further repairs to the area in question were carried out in August 2017, with a more permanent repair in July 2018.

- The fact that the Defendant carried out a repair following the email from the Claimant's children does not imply any kind of admission that the area in question needed to be repaired, and is not relied on by the Claimant as such. However, Mr Dalton, for the Claimant, does rely on the speed of repair and the fact that Mr Gell gave the repair the highest possible priority, implying, he suggests, an acknowledgement that the highway was dangerous at this point.

- From the descriptions of the accident contained in the witness evidence, it is clear that, as she emerged from the Jet garage on to Leagrave High Street, the Claimant experienced a disastrous loss of control of her Ducati motorcycle which led to it accelerating straight across the road and into Ms Tunnicliffe's Chrysler Grand Voyager motorcar. The basis for this claim is that the cause of that loss of control was the motorcycle striking a dangerous road surface for which the Defendant was responsible under the Highways Act 1980. The issues that arise in this case are therefore:

- In considering this issue, I make two preliminary points. First, on the basis of the evidence which I heard, I have no difficulty in rejecting, as a cause of loss of control of the motorcycle, contact with any kind of spillage or contaminant on the forecourt of the Jet garage such as diesel, oil, petrol or the like. This was effectively excluded by PC Jenkin and PC Hollingsworth, and also by Mr Toombs, Mr Smith and Minty when they inspected the garage forecourt. Furthermore, the Ducati motorcycle was examined by Mr Lee Colyer, a vehicle examiner employed by Bedfordshire Police, and he found nothing of note on the tyres. Indeed, he found no other defect either. The second preliminary point is that, as Mr Clarke submitted in his opening skeleton argument, it is necessary for the Claimant to show that the particular point of the highway which caused the accident was dangerous. This entails, of course, establishing the route or trajectory taken by the claimants motorcycle. As Lloyd LJ held in James and Another v Preseli Pembrokeshire District

- It is appropriate, in my judgment, to divide this first issue into 2 questions: first, as a matter of motorcycle handling and physics, what happened to cause the motorcycle to shoot across the road and into the Chrysler; second, whether the fact that this happened is attributable to the defect in the road of which complaint is made.

- In relation to the first of these questions, I heard evidence from accident reconstruction experts and also experts in the handling of motorcycles. All the experts who gave evidence were impressive witnesses whose evidence was capable of acceptance. Mr Brian Henderson, the Defendant's motorcycle expert, was taken by Mr Dalton through the controls of the Ducati being ridden by the Claimant. The right hand controls the throttle and the front brake. The throttle is increased by twisting the right handlebar towards the rider. The right foot controls the rear brake. The left hand holds onto the handlebar and also controls the clutch lever, which is used for changing gear and to disengage the engine. Mr Henderson also described how the clutch lever can be used to regulate power to the rear wheel through partial engagement. He described how good clutch operation is fundamental to proper control of the motorbike. There are five contact points of the body with the motorcycle: each hand, each foot and the seat. These can all help to control steering. The gears are a standard one down and five up with neutral lying between the first and second gear.

- Mr Christopher Taylor doubled up as an expert in both accident reconstruction and motorbike handling. He described a process known as "slip and grip" whereby the rear wheel of the motorcycle, which provides the power (rear wheel drive), may lose traction for various reasons including a reduction in the "coefficient of friction" as different road surfaces are encountered. An extreme example would be if the rear wheel came off the ground altogether. Then, as the rear wheel re-gains traction, the motorcycle may lurch forward. Mr Henderson also described a phenomenon known as "whisky throttle". He said:

- Mr Henderson, for the Defendant, agreed with Mr Taylor's above description of how there could be loss of control. He added into the mix the fact that this make of Ducati motorcycle has been reported to have a throttle response which is particularly "snatchy". He himself owned the same model and he said that when he bought his motorcycle, he read a number of reviews and was aware of this potential problem with the throttle. He described how, with his motorcycle, it had a tendency to lurch forwards and that it took a little time to master. However, it must be said that, when questioned about this, the Claimant said that she had never encountered the "snatchy throttle" problem and I accept that evidence.

- Mr Henderson said that if the Ducati lost traction as it set off to turn left from a 45° position or was in the process of turning left, he would have expected the rear to move towards the offside i.e. anticlockwise (the arc of the motorcycle movement inducing the same) and this in turn could cause the front wheel to turn to the right relative to the body of the machine. He was of the opinion that the loss of control most likely occurred at the moment the power was applied to the rear wheel. He postulated a number of different potential causes whereby the machine could become "unsettled" including power being applied when the real tyre was positioned on a loose stone sett, poor control of the machine upon set off or diesel contaminant upon the rear tyre.

- Mr Paul Fidler, for the Defendant, gave calculations for the speed of the Chrysler and the Ducati. So far as the Chrysler is concerned, he relied upon Mr Hollingsworth's evidence that the Chrysler had travelled for approximately 4-6 metres after the collision. However, Ms Tunnicliffe's evidence was that she was stationary at the time of collision, and I was impressed by her evidence which I consider to be reliable. This would mean that all the speed and force at impact came from the Ducati. Mr Fidler stated that it was not possible to calculate the impact speed of the Ducati, but in first gear the motorcycle could have been travelling at up to 42 mph. He calculated that it would take in the region of 28 metres and 2.7 seconds for the Ducati to reach 42 mph at maximum acceleration. As the distance travelled by the Ducati to the point of collision was approximately 25 metres, the Ducati could have been travelling at up to approximately 42 mph when it reached the Chrysler if maximum acceleration was applied. From the damage to the vehicles, he considered that the closing speed, that is the combined speed of both vehicles was somewhere between 30 and 40 mph. As stated, on the basis of Ms Tunnicliffe's evidence, the closing speed all came from the Ducati which I find had reached a speed of between 30 and 40 mph at the moment of collision.

- Putting together the lay and expert evidence, and answering the first question, in my judgment what occurred was this:

- The second question within this first issue is whether the loss of grip of the rear wheel was attributable to the defect in the road of which complaint is made.

- The Claimant having no recollection of the accident herself, her case is exquisitely dependent upon the evidence of Mr Smith that he saw the back wheel of her motorbike go into a rut and that it was this which precipitated the loss of control and the accident.

- In his statement, he said that he had lived and worked close to the area where the Jet Service Station is, for the last 37 years. He said that he does not use this garage to fill up his motorbike as there is a "close to permanent deep rut on the exit". He said:

- For the Defendant, Mr Clarke submits that the evidence of Mr Smith is unreliable and should be rejected for the following reasons:

- Mr Clarke submits that what has happened here is that, having seen the defects in the road, Mr Smith has worked backwards and now believes he saw the wheel enter the rut or pothole. He submits that, without Mr Smith's evidence, there is no evidence upon which the court can rely to support the conclusion that the Claimant rode over the defective part of the road at issue. This submission is, he says, strengthened by the general rule that a motorcyclist does not ride over a pothole unless it cannot be avoided and the Claimant had enough experience to know this. The Claimant had the opportunity to avoid the rut or pothole because she was riding from the forecourt at low speed and the exit was wide. Furthermore, Ms Tunnicliffe said that the Claimant emerged from a different point, not the one where she would have encountered the defect complained of.

- For the Claimant, Mr Dalton poses the question: if the Claimant did not ride over the rut or pothole, what was it that caused her, a cautious, mature and sensible motorcycle rider, to have lost control so spectacularly. If (as I have in fact found) there was a 'slip and re-grip' then by far the most likely explanation is that the Claimant rode over the defect which was liable to cause this phenomenon. Mr Dalton's second argument places reliance on the evidence of Mr Toombs who said that Mr Smith pointed out to him the defective area immediately after the accident, and after the Claimant had been taken away in the ambulance. Thus, in his statement he said:

- So far as Ms Tunnicliffe's evidence is concerned, Mr Dalton submitted that, firstly, she agreed that the route which she says the motorbike took coming out of the garage was an approximation only. Secondly, the route suggested, showed a 90° turn which, he submitted, would be an extraordinary manoeuvre and a very unnatural way to exit a bell-mouth. Thirdly, he submits that Ms Tunnicliffe would not have been paying the motorcycle particular attention until the Claimant lost control. Furthermore, Ms Tunnicliffe's reliability is weakened by the fact that her indication of where the collision took place was plainly wrong.

- Despite Mr Dalton's arguments, I have come to the conclusion that, on the evidence, I am not satisfied, on the balance of probability, that the Claimant rode over the particular defect of which complaint is made. As stated, in order to make good this suggestion, she is almost wholly dependent on the evidence of Mr Smith and I am afraid that, for the reasons propounded by Mr Clarke, I did not find his evidence reliable. In particular, if, as Mr Smith said, he saw the Claimant ride over that defect and given his own experience only a few weeks earlier, I find it unexplainable that he did not mention this to one of the police officers at the scene or, alternatively, let the police know on a later occasion. He gave a short explanation of what he had seen at the time to PC O'Mahoney but made no mention of the rut. Furthermore, if he had seen what he considered to be a dangerous part of the highway cause such a serious accident, I would have expected him to have reported it to the Local Authority. As Mr Clarke submitted, I find that Mr Smith has reconstructed this and has come to convince himself that this is how the accident occurred.

- It is appropriate that I should deal with Mr Dalton's principal two arguments. First, so far as Mr Toombs is concerned, I regret that I found him to be an unsatisfactory witness. He was a witness who was incapable of answering the question he was asked, his answers rambled on without focus and in any event, the Claimant was in his blind spot at the critical moment. His evidence about Mr Smith pointing out the defect immediately after the accident was, as it seems to me, effectively cancelled out by him saying that they had looked for diesel on the forecourt - a redundant exercise, as Mr Clarke submitted, if Mr Smith already knew what had caused the accident.

- So what, then, caused the Claimant to lose control, to cause the "slip and re-grip" which occurred if it was not the state of the carriageway? The answer is to be found, it seems to me, in Mr Smith's evidence that something similar happened to him on the one occasion that he used this garage on his Kawasaki motorbike. This was, however, nothing to do with the defect of which complaint is made in this case. It may be that there is something about the overall structure of the exit from the garage - the camber together with the different surfaces (including the granite setts which line the exit) with their different coefficients of friction - which causes a degree of difficulty for motorcycle riders. Mr Smith, with his greater experience and expertise, was able to control the problem and exit the garage without coming off his motorbike. As Mr Henderson explained, clutch control is critical in such circumstances and a momentary loss of concentration may have caused the Claimant to misjudge things at the critical moment. I find this all the more likely as she would have been anxious to join the line of traffic at just the right moment so as to slot in behind Minty and in front of Mr Smith, and in her hurry to do so, she perhaps let go of the clutch too quickly causing the motorbike to lurch forward thereby setting off the train of events which I have described. It may also be that, on this occasion, her Ducati displayed the "snatchy" characteristic described by Mr Henderson: if so, it would have taken the Claimant by surprise as she had not experienced this before. The point of all this is that, contrary to Mr Dalton's submissions, I do not find that the facts of the accident point inexorably to a significant problem with the carriageway: there are a multitude of factors which could have contributed, and I find the evidence pointing towards the particular defect of which complaint is made as being the culprit unconvincing and unreliable. Although Mr Dalton suggested that the defect lies in that part of the exit over which traffic would naturally pass, what is true for motorcars is not necessarily true for motorcycles and the Claimant had a choice as to which part of the wide exit she would use. Again, as Mr Clarke submitted, it is implausible that she would have chosen the part which included a rut or pothole which was clearly visible to her.

- It was common ground between the parties that, in considering the issue of dangerousness, I should apply the test laid down by Steyn LJ (as he then was) in Mills v Barnsley Metropolitan Borough Council [1992] PIQR:

- In relation to the state of the highway at the relevant point, I heard evidence from two officials of the Defendant: Mr Mario Kotsanpapas who was responsible for carrying out the inspection of this part of the highway, and Mr Dale Eggleton, the Defendant's Highways Maintenance Manager. I also heard from two highways experts, Mr Philip Reynolds and Mr Peter Dixon.

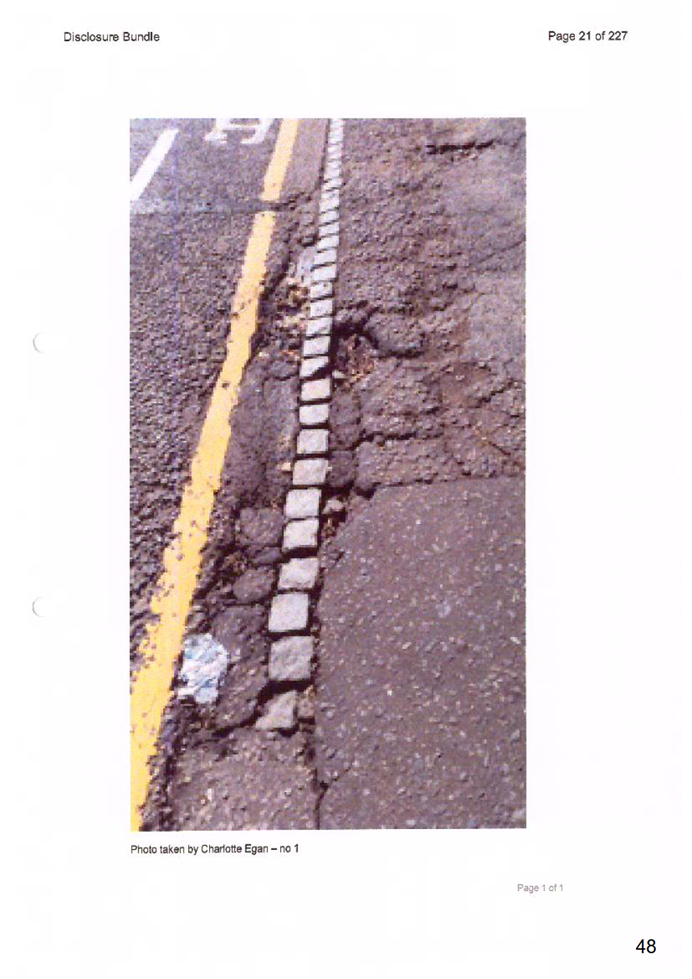

- The experts reached a substantial level of agreement, as reflected in their joint statement. They considered that the photographs provided by the Claimant's children with their email of 26 September 2016 gave the best indication of the condition of the carriageway and footway surfaces at the time of the accident. The photograph that was most used and referred to in the course of the trial was the one at page 48 of the bundles of photographs, now reproduced:

- This part of the highway had been inspected by Mr Kotsanpapas shortly before the accident in a walked annual service inspection on 1 September 2016. He carried out walking inspections of this road four times a year and inspections in a motor car eight times a year. He had not recorded any defects. He stated that the intervention criteria for this type of road would, under the Defendant's then applicable policy, have been a defect 150 mm wide and 50 mm deep. He did not consider that this defect met the Defendant's intervention criteria. Mr Kotsanpapas also described the Defendant's system by which service requests from members of the public are logged. There had been no complaints or reports about this part of the highway in the 12 months prior to the receipt of the email from the Claimant's children on 26 September 2016. Mr Kotsanpapas' evidence was supported by Mr Eggleton who stated that he would not have expected a highways inspector to have ordered a repair, looking at the photographs of the area around the time of the accident. He explained that although Mr Gell had ordered a repair using the highest priority, this did not indicate acknowledgement that the highway needed to be repaired in such haste. He said that after an accident of this kind, swift repair may be carried out at the Defendant's discretion as part of its public relations. He said:

- The experts agreed that the defects on the vehicle crossover should have been recorded in accordance with the Defendant's policy. Despite this agreement, this was not something that Mr Eggleton was prepared to concede. Mr Dixon was of the opinion that the defects should have been assessed either as requiring repair during the next available programme or should have been scheduled for a more detailed inspection. Mr Reynolds disagreed. He referred to the Defendant's own guidance, referred to as the "Luton Risk Register for Highway Safety Defects". Section 5.6 of this document states:

- Taking into account the policy of the Defendant, the opinions of the experts and the photographic and other evidence available, the decision whether a particular defect is or is not dangerous is in the end a matter for the court. In my judgment, these defects were not, as a matter of law, dangerous. In so deciding, I take full account of the greater vulnerability of motorcyclists compared to motorcar users. However, motorcyclists have a greater choice as to which part of the road to use and it is relevant to my assessment that the defective part of the highway could easily be avoided by a motorcyclist exiting the garage. This is in contrast to, for example, a defect in the main part of a carriageway on a bend which a motorcyclist might encounter unexpectedly and when travelling at a speed which did not allow for the defect to be avoided. A motorcyclist exiting the garage would be travelling at a very low speed and would have ample opportunity to see the defect and avoid it. I am influenced by the fact that police officers experienced in the investigation of road accidents, in the belief that they might be investigating a fatality, examined the road and found nothing which, in their view, could account for the accident, thereby indicating that their experienced eyes did not regard the defects as dangerous.

- I also take into account the lack of complaints or reports about these defects. In this regard, I consider apposite what was said by Mrs Justice Swift in Cenet v Wirral Metropolitan Borough Council [2008] EWHC 1407 (QB):

- It follows, therefore, that even if I had found that the accident was caused by the Claimant riding over these particular defects and losing control as a result, her Claimant would nevertheless have failed because the highway was not dangerous.

- In the light of my findings on the first and second issues, it is unnecessary for me to consider Issues 3 and 4, which, in the circumstances, do not arise.

- At the end of the trial, I expressed my sympathy to the Claimant for the injuries she had sustained and for her continuing disability. I repeat those sentiments, but unfortunately sympathy cannot form a basis for recovery and, on my assessment of the evidence, this claim must be dismissed.

Covid-19 Protocol: This judgment was handed down by the judge remotely by circulation to the parties' representatives and BAILII by email. The date of hand-down is deemed to be as shown above.

MR JUSTICE MARTIN SPENCER :

Introduction

Background Facts

"We treated her almost as our 'apprentice'. Lou is a perfectly competent rider, but she is inexperienced and perhaps overly cautious."

Mr Richard Toombs stated:

"Lou is both a novice and a cautious motorcyclist. I would say that she is cautious to the point of over-hesitant. She can ride perfectly well, but she, if anything, is too cautious and not definite enough in her riding."

The Accident

"As I rode down Leagrave High Street, which is a straight road, I saw Lou waiting on the garage forecourt at an angle to pull out. … Lou pulled out in her usual fairly slow and steady way. I was on the inside and probably something like 20 metres away from her when she pulled out and Dell was to my outside and some distance back. I cannot say exactly how far Derek was away from me because my concentration was on Lou, but at this point she was angled at 45 degrees on the garage forecourt; she started moving off and then I saw her back wheel drop into the rut which I knew was there and moved to the nearside. Both of her feet shot out of the foot pegs and her backside lifted clear out of the seat. Her bike was toppling towards the kerb. I then clearly heard the sound of the throttle picking up. I then saw the front end of the bike lift up, I cannot call it a wheelie because it was completely out of control. Lou's only solid point of contact on her motorcycle were her hands. Lou then launched in this completely uncontrolled way into a silver people mover."

He said he heard the Claimant scream in panic as she shot across the road and into the car coming the other way.

"As she pulled out she immediately lost control of the bike. She snaked very fast backwards and forwards across both sides of the road. When I saw this I swerved towards the pavement to try and avoid her. I also braked. The front wheels of my car mounted the pavement when I swerved and my car came to a complete stop with the front passenger side wheel on the pavement. The motorcycle came straight towards me and had hit the front driver's side wing of my car. I had come to a stop and was stationary when she hit me. The rider came off the bike and was thrown forward hitting my windscreen. The windscreen smashed and both the rider and the bike then landed in the road towards the back of my car."

"As the motorcycle approached the Chrysler the front wheel appeared to turn at a right angle and the motorcycle headed straight across the road divide towards the Chrysler. I'm not able to describe the motorcycle at all but the rider appeared to be trying to regain control. I did not see where the motorcycle had come from. The rider appeared to have lost control because the front wheel seemed to have turned at a sharp right-angle so that it faced the opposing carriageway. I instantly knew that I was about to witness a collision as it appeared completely unavoidable. The motorcycle headed straight into the Chrysler. I could also see that the driver of the Chrysler had started to steer towards the pavement to try to avoid the motorcycle which was heading towards her."

"Tony was ahead of me, probably about 20 yards or so and Lou pulled out in front of Tony, as he was expecting her to do, I am sure, and then suddenly everything went horribly wrong. I saw Lou take off at approximately a 45 degree angle from the forecourt. … I saw the rear wheel snake, that is move violently from one side to the other. I saw Lou's front end of her bike come up almost immediately after the snake and with her front wheel in the air, the bike, with Lou still on it, hit a silver people carrier. She hit the door/windscreen pillar and pirouetted on the screen and front door."

As will be seen, however, I consider this account to be, at least in part, inaccurate because the physical evidence indicates the fact that the front wheel of the Ducati hit the off-side front bumper of the Chrysler which indicates that the front wheel was either on the ground or very close to the ground at the moment of collision.

"She told me that the claimant was riding the motorcycle out of the petrol station and appeared to lose control. Mrs Tunnicliffe indicated to me that the claimant had come across the road directly towards her car rather than turning to the rider's left and travelling towards the mini-roundabout. Mrs Tunnicliffe said that the rider was coming towards her but the handlebars were turned at a right angle. She gestured with her hands to show me what she meant indicating that the handlebars had been locked to the side and not facing the direction that the bike had been travelling in. I do not now recall what way she said the handlebars had been turned. Mrs Tunnicliffe said that she had tried to steer away to avoid the motorbike but had nowhere to go."

He also took brief statements from Mr Smith and Mr Toombs. Mr Toombs said:

"I was coming down the road. She came out of the garage and I saw the bike come up and swayed and hit the car."

Mr Smith said:

"We was coming down here. We were meeting Lou at petrol station to then head to the club. As she came out petrol station, Minty was in front and she was behind. Her back wheel slid, she tried to correct it. As she corrected it she was headed towards the car and hit it."

Mrs Gendi said:

"I was in the car behind the one involved in the accident. The bike came out of the petrol station and the wheel kind of came up and buckled and like it jammed itself at a right angle and the person came off the bike. It looks like the biker hit the car. There was nothing the car could do."

"While I was on the scene I do not recall seeing anything obvious that the claimant could have slipped on or anything else that could have caused her to lose control. I am now advised that the claimant alleges that she may ridden over a dip or something similar in the road's surface which caused her to lose control. I was not aware of this being raised as possibility at the time and I do not recall seeing anything on, or in, the road surface, that led me to believe that it could have been a contributory factor in the collision."

"I can say that I inspected the surface of the road between the forecourt and the point of impact while I was looking for the diesel spillage which had been suggested at the time. When I carried out that inspection I saw that there were some points where the tarmac had broken up close to the edge of the carriageway but did not consider these to be a potential contributory factor at the time. If there had been a defect that I thought could have been a contributory factor I believe that PC Hollingsworth and I would have noted this."

PC Jenkin gave evidence at the trial and, in answer to a question from the court, stated that his inspection of the garage forecourt effectively eliminated spillage as a cause of the accident.

"Following the investigation I was unable to establish how or why Ms O'Connor had lost control of her motorbike. In the Policy File I considered three working hypotheses. … The hypotheses I considered were: that the rider may not have been used to the power of the machine, that the rider over-accelerated due to a stuck or faulty throttle or that the rider may have been intoxicated."

In evidence, PS Cordingley confirmed that he had formed the impression that the front wheel of the motorcycle had risen up, that the Claimant had lifted the front wheel and had lost control of the motorcycle.

"I have reviewed the photographs that I took that evening and now note that there is a small hole in the tarmac surface adjacent to the cobbles marking the edge of the footway and carriageway. I had not previously identified this until I was asked about for this statement. I can say that I would have seen this during my visual examination of the road surface but did not consider this to be a potential contributory factor to the collision otherwise I would have commented on it."

In his evidence, PC Hollingsworth confirmed that the FCIU is called in when there is a fatality or a potential fatality. However, he and PS Cordingley confirmed that once they heard from the hospital that the Claimant had regained consciousness and was no longer considered to be in danger of dying from her injuries, the investigation was wound up.

"When I realised she was going to hit me, I braked hard and I was pretty much stopped when she hit me. I am almost certain that I was stationary."

She also said:

"I was aware of the [other] bike coming up the carriageway and stopping allowing her out and then [the claimant's motorcycle] going on its left side, toppling a bit to the left at an angle but not completely to the ground. It then straightened and I thought she had corrected herself and then she suddenly sped across the road in a snaky way."

"Tony knew of the long term defect in the road, and immediately pointed out and said that this was where Lou's wheel had dropped. I saw a rut in the road of about 2 ½ to 3 feet long. I could see that the rut was also full of crud. All 3 of us went back to the garage. We did look for diesel on the forecourt but there was none."

Events subsequent to the accident

"For your attention we are notifying your department about a serious road accident which occurred outside the Jet petrol station exit in Leagrave High Street Luton on 13 September 2016 at approx. 19:15.

Our mother was subject to a number of injuries in which she was in ITU and HDU for over a week before moving to a ward whilst her brain swelling and brain bleed is monitored closely.

Subject to the police report, we are of the opinion that the accident was due to the nature of the pothole which is over 1 m in length and depth able to trap a motorbike wheel when the rider is turning left out of the garage. It is also showing petrol/diesel due to its position between the garage/road.

If the police report agrees with our opinion then we will put the material in the hands of our solicitors …"

Accompanying the email were three photographs showing the condition of the road at the point where it was said that the Claimant's wheel had become trapped, one of which is reproduced in paragraph 45 below.

The Issues

i) Whether the condition of the road was the cause of the Claimant's loss of control of her motorcycle;

ii) If so, whether the highway at the relevant location was in such a condition that it was dangerous to traffic and this dangerousness was the cause of the loss of control;

iii) If so, whether the dangerous condition resulted from a breach of the Defendant's duty under section 41 of the 1980 Act to maintain, repair and keep in repair the said area of the highway so that it was safe for all classes of person and vehicle that might reasonably be expected to use it;

iv) If so, whether the Defendant can avail itself of the defence under section 58 of the Highways Act 1980 that "It had taken such care in the circumstances was reasonably required to secure that the part of the highway to which the action relates was not dangerous for traffic".

Issue 1: was the condition of the road the cause of the Claimant's loss of control of her motorcycle?

Council [1993] PIQR P114:

"The question in each case is whether the particular spot where the plaintiff tripped or fell was dangerous … But if the particular spot was not dangerous, then it is irrelevant that there were other spots nearby that were dangerous or that the area as a whole was due for resurfacing.

This point was made crystal-clear by the decision of this court in Whitworth v. The Mayor, Aldermen and Burgesses of The City of Manchester. In that case the decision in favour of the plaintiff had been founded on the ground that the pavement as a whole was in poor condition. The Court of Appeal rejected that approach. Russell L.J. said at page 6 of the transcript dated June 17, 1971: "The relevant question is whether that which caused the accident constituted a danger, not whether nearby differences in levels which did not contribute to the accident constituted a danger."

"In the event of any of the previously described motor vehicle movements it would be reasonable to expect the rider to attempt to regain control of the machine, and in doing so may have had hand movement on the handlebars that increased throttle input and suddenly caused the vehicle to accelerate in the direction it was facing at the moment of applied acceleration. … This gripping of the throttle as a motorcycle loses stability is a well-known reaction in motorcycling and is known as "whisky throttle" – the natural human reaction to a danger is to tighten up. This is not indicative of an inexperienced road motorcyclist, and is similar to the "unexpected or unintentional acceleration syndrome" where a driver applies acceleration without intending to, and it can take several seconds for a driver or rider to react to such input. During this time a motorcycle would travel a considerable distance and increase speed before either the rider regained control or a collision occurred.

… Novice dirt riders will often grip the handlebars hard in a panic and thus provoke the throttle. The witness statements given to the police are consistent with this loss of grip and regrip. The motorcycle thereafter lurching forward is indicative of "whisky throttle".

i) As the Claimant left the forecourt of the garage and joined the road, there was a momentary loss of grip to the rear wheel which caused it to spin faster.

ii) When the rear wheel regained traction, it caused the motorcycle to lurch forward, and whether because the Claimant's hands were slightly cocked or because she instinctively gripped the handlebars harder, the throttle was increased significantly: the phenomenon know as "whisky throttle" occurred.

iii) The effect of the combination of the re-grip of the rear tyre and the increase in power was to cause the front wheel of the motorcycle to lift up in a form of involuntary "wheelie".

iv) The motorcycle, now out of control, slewed across the road with increasing speed and at some stage both Ms Tunnicliffe and Mrs Gandi saw the front wheel turned almost at right angles to the motorcycle. For this to have been observed, the front wheel must have been off the ground as, had the front wheel been on the ground at right angles to the motorbike, it would immediately have fallen over.

v) The Claimant struggled unsuccessfully to regain control of the machine. With hindsight, she should have disengaged the engine by operating the clutch, but whether out of inexperience or panic, she did not do so, maintaining power to the rear wheel and increasing speed to the motorbike. Just before impact, the front wheel came down so that, at the moment of impact, it was either on the ground or very close to the ground.

vi) The front wheel hit the front offside bumper of the Chrysler with considerable force throwing the Claimant over the handlebars so that she struck and shattered the front windscreen before landing on the ground, thus sustaining her serious injuries.

"I had used it fairly shortly before the collision, and even though I was aware of the rut, on my motorcycle, which is a Kawasaki ZX6R, even with knowledge of the rut, as I exited to turn right, I hit the rut square on (as opposed to Louise who hit it at an angle which I will explain later) my rear wheel span up and my motorcycle started toppling to one side. I regard myself as a significantly more experienced motorcyclist than Louise and because I also "drag race" I'm used to the sensation of a rear wheel "spinning up" and losing traction, so I did not have a panicky reaction, and I knew that the tyre would re-grip, which it did, and whilst I was lurched out of the defect, through experience and knowing that the rear wheel was going to re-grip I managed to divert my course and make the right turn. … I can say from my own personal experience that the defect in the road had been there for many, many years, it was almost permanently in the state of disrepair shown in the photographs I have seen. As a pretty experienced motorcyclist I actively avoided using that filling station, because the defect was such that it made my own motorcycle, which is a sports motorcycle, very unpredictable in its handling."

In cross-examination, Mr Smith confirmed that he used the garage only once on his motorbike, a few weeks before the accident but he had used it on other occasions with his van. Importantly, he said that he had not exited the garage at the same point as the Claimant. He said that her rut was deeper than the one which had almost caused him to lose control. He was asked by Mr Clarke why he had not told the police about the rut causing the accident, and he said:

"I don't even remember speaking to the police. After she was put into the ambulance, it is a haze. I was drained: it is different when it happens to someone you know and you see it from start to finish."

He was asked by Mr Clarke why he had not informed the Local Authority of the condition of the road and he said he couldn't answer that. He also said:

"I didn't tell anyone at the scene what I saw."

i) His account of the accident was first given in his witness statement of May 2019 and no mention of the wheel of the motorcycle entering a rut was made to the police at the time, which is a surprising omission. The police officers said in evidence that the witnesses at the scene were asked open questions such as "what did you see" or "what happened next" but he did not say that he saw what he now says he saw. I have referred to PC O'Mahoney's evidence where he said:

"I am now advised that the claimant alleges that she may ridden over a dip or something similar in the road's surface which caused her to lose control. I was not aware of this being raised as possibility at the time and I do not recall seeing anything on, or in, the road surface, that led me to believe that it could have been a contributory factor in the collision."

ii) It is also surprising that, if he did see the accident and the cause, and knowing (as he says) that he had encountered a similar problem and knowing that the Claimant had been seriously injured, he did not report the matter to the Local Authority.

iii) There is a dispute of evidence as to the precise route taken by the Claimant as she left the Jet garage. The exit is some 8 ½ metres wide with the particular area identified by Mr Smith as where the Claimant lost control near the middle. However, Ms Tunnicliffe said in her evidence that the Claimant came out from the right-hand side of the exit as you leave the petrol station and, Mr Clarke submitted, if that is right, then the Claimant did not encounter the particular defect at issue in this case.

iv) Mr Smith's graphic description of the Claimant being thrown out of her seat and with her feet off the "pegs" with the front wheel up in the air and with the motorcycle travelling a distance of 25 metres or so from the point of the alleged defective area to the point of impact with the Chrysler Voyager motorcar is, Mr Clarke submitted, implausible. The Defendant's accident investigator, Mr Paul Fidler, gave unchallenged evidence that the front wheel of the motorcycle hit the front offside bumper of the Chrysler which meant that the front wheel was either on the ground at the point of impact or very close to the ground. Mr Clarke submitted that if the front wheel had been up in the air from the time of loss of control to the time of impact, the motorcycle would have toppled backwards.

v) Mr Henderson, the Defendant's expert in the handling of motorcycles, had difficulty with Mr Smith's description of the accident and thought that it in fact suggested a loss of control prior to the motorcycle encountering the defect.

vi) Mr Clarke also relies on the inherent unreliability of recollection of traumatic events. He cites the dictum of Moore-Bick LJ in Goodman v Faber Prest Steel [2013] WL 617359 where he said, at paragraph 17:

"Although much emphasis is quite properly placed on the advantage given to the trial judge of seeing and hearing a witness give evidence, it is generally acknowledged that it is difficult even for experienced judges to decide by reference to the witness's demeanour whether his evidence is reliable. Memory often plays tricks and even a confident witness who honestly believes in the accuracy of his recollection maybe mistaken. That is why in such cases the court looks to other evidence to see to what extent it supports or undermines what the witness says and for that purpose contemporary documents often provide a valuable guide to the truth."

vii) Mr Smith's evidence that he saw the rear wheel of the Claimant's motorbike enter the rut and he therefore knew this was the cause of the accident at all times is undermined by the fact that he, Mr Toombs and "Minty" walked the forecourt looking for contaminants, a redundant exercise if Mr Smith already knew what had happened.

"Tony, Minty and I walked back to the garage, Tony knew of the long term defect in the road, and immediately pointed it out and said that this was where Lou's wheel had dropped. I saw a rut in the road of about 2 ½ to 3 feet long."

In the course of cross-examination, Mr Clarke referred Mr Toombs to page 649 of the bundle where a photograph of the defect in question is included in the report of Mr Dixon, one of the highways experts, and asked whether these were the defects which Mr Smith pointed out on the day in question. Mr Toombs replied:

" Yes, the two together, he didn't distinguish between them. He said that this was where she went over and that is where the potholes were. It is where he said she came off the bike. The area of the potholes was where Tony said she came out of the garage."

Mr Clarke challenged this, asking why it had not been mentioned to the police at the time. He also asked why Mr Toombs had not reported the rut to the local authority to which he replied: "I didn't see it myself, I would have been guessing." Mr Dalton puts Mr Toombs forward to the court as an honest and reliable witness whose evidence, if accepted, substantially corroborates the evidence of Mr Smith and establishes that the Claimant rode over the rut or pothole and it was this which caused her to lose control of the motorbike.

Discussion

Issue 2: was the highway at the relevant location was in such a condition that it was dangerous to traffic and this dangerousness was the cause of the loss of control;

" All that one can say is that the test of dangerousness is one of reasonable foresight of harm to users of the highway, and that each case will turn on its own facts. Here the photographs are particularly helpful. In my judgment the photographs reveal a wholly unremarkable scene. Indeed, it could be said that the layout of the slabs and the paving bricks appears to be excellent, and that the missing corner of the brick is less significant than the irregularities and depressions which are a feature of streets in towns and cities up and down the country. In the same way as the public must expect minor obstructions on roads, such as cobblestones, cats eyes and pedestrian crossing studs, and so forth, the public must expect minor depressions. Not surprisingly, there was no evidence of any other tripping accident at this particular place although thousands of pedestrians probably passed along that part of the pavement while the corner of the brick was missing. Nor is there any evidence of any complaint before or after the accident about that part of the pavement. Like Mr Booth, I regard the missing corner of the paving brick as a minor defect. The fact that Mrs Mills fell must either have been caused by her inattention while passing over an uneven surface or by misfortune and for present purposes it does not matter what precisely the cause is.

Finally, I add that, in drawing the inference of dangerousness in this case, the judge impliedly set a standard which, if generally used in the thousands of tripping cases which come before the courts every year, would impose an unreasonable burden upon highway authorities in respect of minor depressions and holes in streets which in a less than perfect world the public must simply regard as a fact of life. It is important that our tort law should not impose unreasonably high standards, otherwise scarce resources would be diverted from situations where maintenance and repair of the highways is more urgently needed. This branch of the law of tort ought to represent a sensible balance or compromise between private and public interest. The judge's ruling in this case, if allowed to stand, would tilt the balance too far in favour of the woman who was unfortunately injured in this case. The risk was of a low order and the cost of remedying such minor defects all over the country would be enormous. In my judgment the plaintiff's claim fails on this first point."

Furthermore, In Dean and Chapter of Rochester Cathedral v Debell [2016] EWCA Civ 1094, Elias LJ, in discussing Steyn LJ judgment in Mills noted at §12:

"It is important to emphasise, therefore, that although the test is put by Steyn LJ in terms of reasonable foreseeability of harm, this does not mean that any foreseeable risk is sufficient. The state of affairs may pose a risk which is more than fanciful and yet does not attract liability if the danger is not eliminated."

The experts agreed as to the dimensions of the defects as follows:

"With regard to ascertaining the size of the defects. It is agreed, based on our experience, that the stone blocks/setts Installed at the kerb line are likely to be nominally 100mm x 100mm In plan and such setts are often 100mm in depth laid on a concrete/mortar bed. From the likely plan dimensions. It can be estimated that the defect at the edge of the vehicle crossover was up to around 200mm wide and 200-300mm in length and the oarrlageway defect was up to around 200-250mm wide and around 800mm in length.

2.8 Whilst we do not necessarily disagree on the matter, Mr Reynolds considers the depth of the defect at the edge of the vehicle crossover was 40-50mm deep, based on a detailed review of the Images at the location and the installation requirements for hot rolled asphalt surface course materials. Mr Dixon considers that the surface course material was evidently old and whilst it was likely to be hot rolled asphalt, In his judgement around 40mm deep, the uncertainty caused by the lack of a suitable reference point in the available photographs means that a range of depth of between 30 and 50mm would be appropriate."

"At the time, our policy was to carry out and repair in response to a fall or accident so as to be seen as a caring Authority. It was a convenience. It shows willing and that we care. A dangerous defect requires an urgent repair, but an urgent repair does not necessarily reflect a dangerous defect and the top priority may be used for convenience at the time."

"It is anticipated that there will be very few variations from the risk factors and priority responses detailed in the register."

Mr Reynolds, in forming his opinion, followed the detailed guidance in this plan as available to the Defendant's inspection team, so as to assess each defect based on its dimensions, location and the hierarchy categories for Leagrave High Street.

"44. There was, however, evidence to support the view that it was not dangerous. Despite its presence in the carriageway for at least a period in excess of two years, no member of the public had complained about it. Nor had any accident, other than that of the claimant, been reported as having occurred there. The photographs showed the type of minor defect that is not unusually seen in the carriageway of a road. It is clearly distinguishable from the adjoining setts and could readily be avoided by a person paying proper attention. I have in mind the observations made by Steyn LJ and Dillon LJ in Mills. It does not seem to me that this defect, situated in the carriageway, and in the location that it was, can properly be regarded as "a real source of danger". The risk it presented was of a low order and the cost of remedying all such defects in the carriageway would be wholly disproportionate."