"'The balance of probability standard means that the

court is satisfied that an event occurred if a court considers that, on the

evidence, the occurrence of the event was more likely than not. When assessing

the probabilities, the court will have in mind as a factor, to whatever extent

it is appropriate in the particular case, that the more serious the allegation the

less likely it is that the event occurred and, hence, the stronger should be

the evidence before court concludes that the allegation is established on the

balance of probability. Fraud is usually less likely than negligence…Built into

the preponderance of probability standard is a generous degree of flexibility

in respect of the seriousness of the allegation.'"

"… I have found it essential in cases of fraud, when considering

the credibility of witnesses, always to test their veracity by reference to the

objective facts proved independently of their testimony, in particular by

reference to the documents in the case, and also to pay particular regard to

their motives and to the overall probabilities. It is frequently very difficult

to tell whether a witness is telling the truth or not; and where there is a

conflict of evidence such as there was in the present case, reference to the

objective facts and documents, to the witnesses’ motives and to the overall

probabilities can be of very great assistance to a judge in ascertaining the

truth.”

"It would not, I think, be difficult to say that in most

cases a prediction about the future (particularly in the context of contractual

negotiations) would necessarily be understood as implicitly representing that

the maker of the prediction had an honest belief in it. The existence (or

otherwise) of a belief is a present fact at the moment that the prediction is

uttered. If, therefore, the maker of the prediction does not have an honest

belief in the prediction at the time when he makes it, he will have made a

false representation of fact. In other cases, further implications may be

appropriate. It may be that the representation would necessarily be understood

as meaning that the prediction is based on reasonable grounds; or that the

maker of the prediction has the present intention to do what he can to make it

come true."

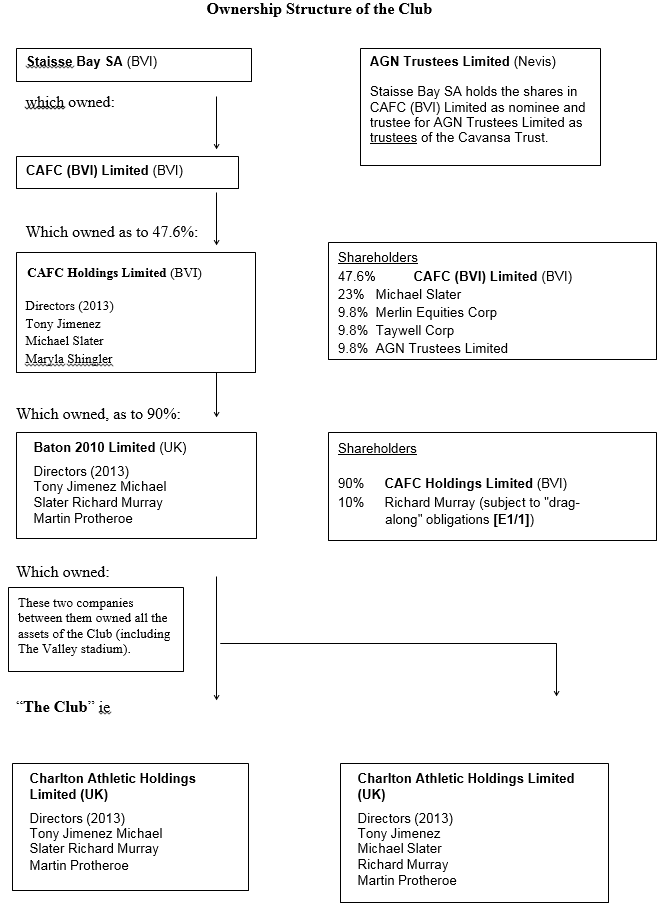

(iii) The Greenwich

Peninsula development

(a) The

Masterplan: April 2012

29.

The Land Deal concerned the possibility of the parties participating in

some aspect of the Greenwich Peninsula development. During 2010/2011 Greenwich

Borough Council (“Greenwich” or “the Council”) began work on a Masterplan (“the

Masterplan”) for the development of industrial land on the west side of the Greenwich

Peninsula close to the O2 entertainment venue.

30.

In April 2012 the Council published a Masterplan for the development.

This envisaged the construction of a mixed-use area including leisure,

education, employment and housing. The Masterplan constituted a “Supplementary Planning

Document” (“SPD”). The status of the Masterplan as an SPD meant that, whilst

not amounting to adopted Council policy, it nonetheless could be used as a

material consideration when assessing planning applications. It amounted to a

development framework which was, as stated in the Masterplan, intended “… to

steer development in this part of the Royal Borough for years to come.” The

Masterplan described the area to the west side of the Greenwich Peninsula

as a relatively underdeveloped area that had been held back by two century old

factors: the remnants of its industrial history and the southern approach to

the Blackwell Tunnel. The site was described as having “huge potential”.

Implementation of the Masterplan would create a new “world class district

for London”. The Masterplan set out the relevant “Objectives”. The

first objective was in the following terms:

“To transform the contribution of the area to the Royal

Borough and the sub-region by focusing development and regeneration around a

new multi-purpose sports/entertainment/education facility that links with, and

complements the offer at the O2 Arena.”

31.

Later in the Masterplan under the heading “Sports/Leisure/Education

complex” the following was stated:

“A multi-use facility is to be

centrally positioned within the Masterplan. A key role for it would be to

provide outdoor entertainment linking with and complementing the offer at the

O2 Arena. The complex could also be integrated with an elite sports facility or

university. At ground level the complex could contain retail and hospitality

uses creating an active edge when not in use.

The western edge of the complex

could be quite low lying, perhaps initially simply a land form. Lowering the

western edge allows for views out towards Canary Wharf, and access by

pedestrians along the river walk.

Any development of the complex will

be dependent on the release of the safeguarded Tunnel Wharf.”

(b) The Lisney advice:

February 2013

32.

Mr Michael Slater (Chairman of the Club and significant minority

shareholder) sought professional advice on the potential for the Club to

relocate from its existing stadium at the Valley to a new facility potentially

to be built on the Greenwich Peninsula. Advice was given by Lisney, Chartered Surveyors,

(“Lisney”), in a letter dated 13th February 2013. The advice was

said to be preliminary to the carrying out of a more detailed report. The

advice was based upon the Masterplan but also upon attendance at a meeting with

the Leader of the Council and its head of regeneration in January 2013, during

which the Council apparently emphasised the desirability of a stadium to be

constructed on part of the site. The purpose and function of the stadium from a

planning perspective was to provide a buffer between the safeguarded Victoria

Deep Water Terminal to the north of the site and development land to the south.

33.

A complication in any redevelopment of the site lay in the fact that a

part of the land was owned by Morden College. The college is a Christian-founded

charity established in the early 18th century, its purpose being to

assist elderly people by the provision of homes for independent and supported

living and residential care facilities. The freehold owned by Morden

College extended to 34.7 acres. Lisney, on behalf of the club, met with

representatives of Morden College and the Council in January 2013. During this

meeting the Council explained their intentions for the site and their hope that

a stadium would be constructed on part of the site. They hoped that the Club

would commence a dialogue with Morden College to see if there was a way to

advance the development with the construction of a stadium as an early step. Of

relevance was the fact that Morden College had leased the majority of the site

to Cathedral Properties (“Cathedral”) on a 50-year lease from 1994 and a

further part of the site to Hays Chemical Distribution Limited on a lease

expiring in 2037.

34.

One advantage

of the construction of a stadium on the site would be to release approximately

10 acres of land at the south of the stadium which the Council had identified

as suitable for a high-density river-front residential development. The

existing Valley site could also be brought into the deal and be used for social

and affordable housing. The summary to the advice given to the Club was in the

following terms:

“There is a very strong

relationship between CAFC and the Royal Borough of Greenwich and in my view it

is clear that the local Authority would like to see proposals brought forward

showing a relocation of CAFC’s ground to the site they have identified in their

master plan.

The local authority have made it

clear that if economically viable proposals are brought forward which show the

provision of a stadium that they are prepared to robustly defend their master

plan and may use other powers available to them including compulsory purchase

powers to ensure that their vision for the Peninsula becomes a reality.”

(c) Documents prepared for

prospective buyers: February 2013

35.

At around the time when the sale of the Club was being contemplated

(late 2012/early2013) various documents were prepared to provide information to

prospective purchasers. These included information about the possible

development on the Greenwich Peninsula. For instance in one document providing

general information about the Club, there is a description of the Council’s

plan to develop the Greenwich Peninsula site. It is stated that within the Peninsula there was the “Syral Site” and that the Council had made it clear that only if

CAFC was involved and the development included a new football stadium would the

Council support a change in planning status from the current low value

industrial status to the more valuable mixed residential/commercial/ leisure

status. The document stated:

“CAFC hopes to be able to

leverage this opportunity to get a new stadium built for the club free of

charge and then develop the land the existing stadium and training ground sit

on. The existing owners of CAFC would like to become involved at an early stage

of further developments of Greenwich Peninsula.”

36.

A more detailed document relating to the proposed development was

produced in about February 2013. One significance of this document is that it

was provided to the Claimant by the First Defendant during the meetings in Los

Angeles in September 2013 and therefore stands as a fair reflection of the

Land Deal that was being discussed. The document described the position of Morden

College as freeholder and the long leases that it had entered into. There is a

general description of the development potential of neighbouring sites. The

document described the Masterplan. In relation to the possibility of a new

stadium being located within the site the following is stated:

“The area of the proposed stadium

site is c.12 acres. Stadiums are difficult buildings to make work, the most

obvious fit for the stadium is as a football stadium with additional use for

concerts. The only club that could realistically use the stadium is CAFC as it

is in the heart of the core Charlton area and it would be political suicide for

the local council to build a ground to host another team. The Materplan

proposes a 40,000 seater stadium with the ability to increase the capacity.”

37.

The document later proceeds to set out three potential options. The

first would involve the Club acquiring the site from Morden College.

This option contemplated, in substance, the wholesale taking over of the entire

development at a cost of approximately £2 billion. The option postulates that

on such cost a profit of c£0.8 billion could be available. The second option entailed

the Club obtaining a stadium constructed for free and the mortgage on the

existing stadium being repaid. It is stated that the Club maintained a close

relationship with the Council and supported the Council in its belief that a

stadium as part of the overall development was viable. It is stated that the Council

could insist that Cathedral develop the site in line with the Master Plan. The

following is then stated:

“CAFC can make this more

palatable to Cathedral by offering its Existing Stadium to site a large

proportion of the social housing requirement. This would free up an additional

1.3 m sq ft of residential development for sale on the river, adding an

addition £245m profit to the development.”

The third option was that CAFC

would obtain a substantial fee to drop its interest in the site.

38.

It can be seen that a commitment to relocate into the Greenwich

Peninsula site could have unlocked a substantial development potential. However,

the realisation of this potential was contingent upon the Club and/or London

Borough of Greenwich agreeing terms with the freeholder and long-leaseholders.

In addition, detailed and complicated planning permissions would be required.

And, at least if option 1 was pursued, a total development finance of

approximately £2 billion would have had to be secured. If such a development

was to come to fruition it would have taken a considerable period of time.

(iv) The financial crisis

at the Club: 2012/2013

39.

As of 2012/2013 the Club had more or less exhausted its usual lines of

credit. A major obstacle to those involved in the Club, including in particular

the Defendants, becoming involved in the Greenwich Peninsula development arose

from the fact that in 2012 the Club’s finances were weak. The additional

revenue which the Club expected from promotion did not materialise and players’

wages had escalated. The Club was trading at a loss of approximately £5.5m per

annum. The Rose Trust declined to offer additional funding. It became clear to

the directors of the Club that it was in the best interest of the Club for it

to be sold. This meant that any future involvement in the Greenwich Peninsula development

would not be undertaken by the present owners of the Club but would, if there

was to be involvement at all, have to be undertaken by a new owner.

Whether or not the Defendants were able to retain an interest in the

development would therefore become a matter of negotiation during the

course of the sale process.

40.

As I explain below, the Defendants formed the intention to use the sale

of the Club as a lever to secure their continued interest in the Greenwich

Peninsula development post-sale. But of course, if the Club went into

administration, their ability to achieve this goal was severely prejudiced and

in all probability, fatally so.

(v) Potential

buyers of the club. The importance of “skin in the game”

41.

Michael Slater, a qualified lawyer and the Club’s Chairman, always had

at the back of his mind the prospect of the Club being put into administration.

Indeed, the documents reflecting the position at the end of 2013 indicate that

it was only the imminence of the sale to Mr Duchatelet in December 2013 that

held administration at bay (see eg the email at paragraph [62](vii) below). The

need for a quick sale was pressing. As 2013 progressed, potential buyers came

and went. In Summer/ early Autumn it appeared as if a sale of the Club coupled

to a Land Deal would be signed with the US investors Blackstone. However, in

mid-September 2013 a team from Blackstone came to the UK

to conduct due diligence. It became apparent then that the Blackstone team were

divided as to the merits of the transaction. And in fact they did in due

course withdraw.

42.

What is evident from the documentation is that the possibility of being

involved in the Greenwich Peninsula development was of interest to the

prospective purchasers. Mr Slater explained that the way that the team would

approach the buyer was to offer an equity stake in any future development deal.

It is his view that this was a “big selling point”. In his evidence he

explained how one Kuwaiti investor informed him that this would be a “very

attractive plus”. Another potential purchaser engaged in discussions with

Council. Mr Slater also referred in his evidence to the approach made, via an

agent, by one anonymous property developer who appeared more interested in the

development than the football club.

43.

The Defendants fully understood that it was their ability to leverage

their ownership of the Valley stadium that was the key to their being able in

the long term to have a seat at the negotiating table in any major development

on the Greenwich Peninsula. They therefore had to devise a vehicle which

enabled them to sell the Club but retain an interest in the stadium upon

completion. If they failed to do this then they handed all of their leverage

over to the new Club buyer.

44.

The basic model devised for the sale of the Club would leave the

Defendants “with skin in the game” following the sale of the Club to the

new owner. The sale would be implemented through a “Special Project Vehicle”

(“the SPV Ltd”). A draft SPV agreement was before the Court. The drafting of

the model was relatively straightforward. Boiled down to essentials the SPV

agreement with the new owner would commit that new owner (i) to a stadium

relocation and (ii) to dealing only with the Defendants in relation to

the implementation of the stadium relocation.

45.

Of course, to have a chance of retaining “skin in the game”

following the sale of the Club, the Defendants had to be in a position to sell

the Club as a going concern. And therein lay a major problem. As Autumn 2013

progressed, the club’s finances were deteriorating and a financial crisis

loomed. The need for short term finance was critical.

(vi) The September 2013

meetings between the Claimant and First Defendant

46.

This is the context to the meetings that occurred between the Claimant

and the First Defendant, Mr Jimenez, in Los Angeles on the 15th- 17th September

2013. This case turns in large part on what was or was not said during these

meetings. During cross-examination, the course of these three days was explored

and included such issues as the time spent in hotel lobbies engaged in

discussing the deal, which restaurants the parties went to for dinner, what

they ate, who they sat next to, whether Mr Khakshouri took notes during the

dinner, whether they visited the site of a project the Claimant was interested

in, etc. The subtext to this was to either establish or undermine the

credibility of the competing versions of Mr Khakshouri and Mr Jimenez as to

what was said (or not said). I must come to a decision about what was said. I

have set out my conclusions on the evidence in Sections D and E (paragraphs [75]-[117])

below. For present purposes it suffices to set out the competing contentions as

to what transpired as between Mr Khakshouri, and Mr Jimenez. Both individuals

gave detailed oral evidence in the course of this trial. Their respective

positions may be summarised as follows.

47.

Mr Khakshouri said that during these meetings he was persuaded to make a

loan of £1.8m to the Club because Mr Jimenez told him that he and Mr Cash were

the majority shareholders in and controllers of the club, that they were endeavouring

to sell the Club and that the Club needed a short-term loan to ease urgent cash

flow problems. Mr Khakshouri was however reluctant to advance the loan because

such cash as he had available was tied up in the LA Deal that was imminently,

on 18th September 2013, to complete and which was expected to be

highly profitable because he had acquired the development property at what he

considered to be an extremely good price indeed. In order to induce Mr

Khakshouri to advance the loan, Mr Jimenez explained that he and Mr Cash, as

the majority controllers of the Club, had put together a project for the

construction of a new stadium and adjacent mixed residential accommodation and

commercial premises on the Greenwich Peninsula. They would give to Mr Khakshouri

a share of their interest in the deal (i.e. the Land Deal) if he advanced the

Loan.

48.

Mr Khakshouri was ultimately persuaded to make the Loan because Mr

Jimenez promised and assured him that it was the Defendants’ intention, as

majority controllers of the Club, to make the Land Deal a certainty

by ensuring that the Club would not be sold without a property

development agreement being into place with a new purchaser. Mr Khakshouri knew

that what was being promised was no more than an agreement to secure a seat at

the table after the sale of the Club had been completed. But the

potential upside of the Greenwich Peninsula development project was very high

indeed, as the documents provided to him by Tony Jimenez during the discussions

demonstrated. Option 1 (see paragraph [37] above) contemplated a profit of

£0.8b. A slice of that pie- even small slithers- might be very lucrative

indeed. He knew however that for such a project to come to fruition could take

8 or 9 years.

49.

Mr Khakshouri is adamant that it was the express statements and

representations that Messrs Jimenez and Cash were the majority shareholders and

the fact that those two men, with whom he held a relationship of complete

trust, intended to ensure that the Club would not be sold without a

linked Land Deal that made him relent and agree to advance the Loan. The key

fact for him was that his two very close friends were controllers of the Club

and could ensure and guarantee that it would not be sold without the Land Deal

being put into place.

50.

Mr Khakshouri says that in direct consequence of, and reliance upon, the

representations being made to him he then sold part of his interest in the LA Deal

to his brother-in-law (Mr Isaac Cohanzad) and he used the proceeds to make up

£1m of the loan. The balance of 0.8m was then borrowed from his other

brother-in-law, Mr Fred Nayssan, and by drawing upon his other lines of

credit.

51.

It is not disputed that on 16th September 2013 Mr Jimenez

sent, by email, to Mr Khakshouri three documents which set out the details of

the Greenwich Peninsula development and described the options open to the

Defendants (see paragraphs [35] – [38] above). At a meeting on 17th

September Mr Jimenez took him through the proposed Land Deal. Mr Khakshouri made

detailed notes (which were disclosed and were in Court). That meeting lasted

about two and a half hours.

52.

For his part Mr Jimenez explained that in mid-September 2013 he happened

(perchance) to be visiting Las Vegas with his son and brother-in-law to see a

boxing match. He took the opportunity to invite Mr Khakshouri to invest and as

part of the investment to advance the required short-term loan. He says that

the three meetings that he had with Mr Khakshouri between 15th- 17th

September 2013 were essentially social occasions. In total the business

discussions lasted only about 30 minutes. It was all very simple. The Club’s

finances were in crisis. Mr Khakshouri was a very close and dear friend and he

wished to help out. Mr Jimenez stated that he could not recollect all of the

details but he was clear in his own mind about a number of matters. He says

that he explained to Mr Khakshouri that there might be a real estate

opportunity in relation to the Club and that the Council was keen to regenerate

the Greenwich Peninsula and would support a move by the Club to relocate its

stadium to the Peninsula. This was notwithstanding that the Club did not

currently own land in that area and there was no extant planning application or

permission. Mr Jimenez recalls that he described the deal in terms of its

potential and that, although it would be difficult to implement, if it could be

“pulled off” it could be very lucrative. He explained that he emphasised

that it might not materialize but that he would nonetheless be happy to include

Mr Khakshouri in the potential deal as a bonus for making the Loan to the Club.

In his witness statement Mr Jimenez stated as follows:

“67. I explained that it was our

intention to try and secure agreement from the purchaser of the Club that they

would in principle take part in the Potential Land Deal if it proceeded, which

was entirely true and is what we tried to do. I did not say that no sale of

the Club would take place unless the Potential Land Deal was in some way part

of the sale, since we could not foresee what would happen.

68. I recall that Darius was keen

on the 12% return but did not show any particular interest exploring the

details of the Potential Land Deal. He did not ask me to provide further

information about it, did not say he would need to do any due diligence before

making the loan (and indeed never showed any interest in doing so afterwards)

and did not ask to visit the site of the Potential Land Deal, either at the

time or on subsequent visits to London. Darius came to the UK

on at least two occasions after having made the loan. During these visits he

never expressed a wish to visit the site and never did so. My view at the time

was that he understood the speculative nature of the Potential Land Deal and

therefore feels the need to waste time looking at loads of detail, conducting

any due diligence, insisting the deal took centre stage in the loan

documentation or indeed even visiting the site.

69. I did not explain exactly

what role and interest Darius would have in the Potential Land Deal because the

project was still at such an early stage. However, I remember that I made it

abundantly clear to Darius that it was merely a potential project, with no

certainty whatsoever.

70. Although, as I have said, it

was my intention at the time that we would sell the Club to a buyer who would

be committed to the Potential Land Deal (financially and/or in respect of

moving the stadium in due course), and I explained that to Darius. I did not

say to Darius that the Potential Land Deal was certain to proceed because the

Club would not be sold without it. That would have been a ridiculous thing to

say, particularly to an experienced property developer, because it would have

been obvious to him that even if the buyer of the Club was committed (either

financially and in respect of moving stadium, or just in respect of moving

stadium) the project would remain very far from being a certainty. As an

experienced property developer, Darius was well aware that the Potential Land

Deal was in its infancy and would remain very far from being a certainty even

if the buyer of the club was supportive. The Summary Document which I had sent

him on 16 September 2013 also made this very clear.

71. In addition, I did not say

that a lot of progress had been made in the months since the Summary Document

had been produced or that we were certain that the Potential Land Deal would

proceed. We were not, and nothing I could have said could have given Darius, an

experienced property developer, any such impression. I did not provide Darius

with any details suggesting that any progress had been made beyond that. I do

not believe that in those discussions I said that [the Second Defendant] and I

were the controllers of the Club (and certainly did not go into details or

suggest our control was through direct or indirect shareholdings), although as

I have explained Darius had been aware for some time that we effectively

controlled the club. I did say that [the Second Defendant] was aware of and

supported the proposal that I had made to Darius.”

53.

On 20th September 2013 the Claimant advanced £1m to Charlton

Athletic Football Company Limited, the operating company of the Club, and on 23rd

October 2013 he advanced a further sum of £0.8m to the same company. The Loan

was subsequently documented by a written agreement dated 4th

November 2013 (“the Side Letter”- see paragraphs [57]- [59] below). The

borrower upon this occasion was specified as Charlton Athletic Holdings

Limited, the owner of the Valley. It is said that this company was, in fact, a

more secure counter-party for the Claimant.

54.

It is an obvious point, but nonetheless relevant to the analysis, that

the Second Defendant, Mr Kevin Cash, was not physically present at these

meetings in LA, though he was in regular telephone contact with Mr Jimenez. The

Claimant’s case against the Second Defendant relies upon the proposition that

the First Defendant was acting as the Second Defendant’s agent when he made the

impugned representations with actual authority.

(vii) The McGlynn

Restructuring Agreement

55.

I need at this stage to refer briefly to an unrelated transaction. The Defendants

relied upon an agreement concluded with Mr Neil McGlynn which was also designed

to assist to alleviate the Club’s cash flow difficulties. It is relied upon

because it is said that this was essentially the same arrangement that the Defendants

concluded with the Claimant and reflects how much of a “long shot” the Greenwich

Peninsula development was considered to be.

56.

Mr McGlynn had, pursuant to an earlier loan agreement, provided the Club

with a term loan facility of £3m in September 2012. As part of that arrangement

the parties granted to Mr Glynn 10% of such interest as the Defendants held in

the proposed Greenwich Peninsula development. The net effect of the new

agreement was to defer repayments of the loan. Under a heading “Development”,

at clause 4.1, the parties acknowledged that the “Development Parties” (i.e. in

substance the Defendants) were involved in “discussions with various

individuals and companies in relation to the Development but no terms have been

agreed or finalised at the date of this agreement.” In consideration for

the deferment of the repayments that Mr McGlynn was “… entitled to an equity

interest equal to 10% of whatever interest the Development Parties have in the

Development…” The clause goes on to make it clear that the interest being

conferred upon Mr McGlynn was contingent upon the development being carried

out. In his witness statement Mr Jimenez states the following in relation to

this transaction:

“79. The agreement specifically

provided that Neil would not have to pay for his shares or provide any finance

for the development if the Potential Land Deal progressed. Although we did not

go into that detail with Darius, this was essentially the same arrangement that

was envisaged with Darius and reflects how much of a long-shot the Potential

land Deal was considered to be, given that in return for relatively modest

short-term loans paying a generous return we were prepared to give away a

potentially valuable interest in the Potential Land Deal for nothing. If Neil

or Darius had become a shareholder in any development company then, as is

normal, each would have been expected to stand as a party to any guarantee or

indemnity required from shareholders as part of the financing that would be

required for the Potential Land Deal, but we were not expecting them to put up

their own financing.”

(viii) The Side Letter: 4th

November 2013

57.

As explained above Mr Khakshouri advanced the Loan prior to completion

of relevant documentation. Draft documentation was prepared by Mr Graeme Muir,

a colleague of the Defendants. He had not been involved in the negotiations

between the Claimant and First Defendant. He therefore necessarily prepared

documentation upon instructions from the First Defendant.

58.

The draft was sent to all of the parties, including the Claimant, for

comment. It is apparent and not disputed that Mr Khakshouri reviewed the

documentation and sent comments back to the Defendants about its drafting. The

documentation included terms for the Loan, and the Side Letter. The Side Letter

is an important document. Its terms, in full, are as follows:

“Dear Darius

CAFC Property Agreement

We refer to the recent loan of

£1,800,000 (the “Loan”) that you have provided to Charlton Athletic Holdings

Limited of which we are the majority shareholders.

As discussed and in consideration

for you providing the Loan, we have agreed to grant to you (or any other entity

that you may nominate) 30% of the Residual Property (as defined below) that we

hold in Charlton Athletic following the disposal of Charlton Athletic to a

third party purchaser (your “Interest”).

For the purpose of this Agreement,

the “Residual Property” shall mean any interest whatsoever that we hold in the

proposed property development deal for the construction and delivery of a new

football stadium for Charlton Athletic Football Club and other residential

property development at the Syral site on the Greenwich Peninsula in London.

We hereby undertake to hold your Interest

for you (or any other entity that you may nominate) on trust and to provide to

you with all and any profit (after the deduction of reasonable expenses and

government taxes, if any) whatsoever that derives from your interest from time

to time.

As trustees of your Interest, you

agree to allow us to decide how to deal with your Interest (provided always

that we deal with your Interest in exactly the same manner in which we deal

with our own 73% interest). Therefore, and for the avoidance of doubt, you

hereby provide us with permission to utilize and, if thought prudent by us,

dispose of your Interest in any way that we see fit. Our ultimate aim for your Interest

(as it is for our own interest is to maximise profit.

We trust that this letter

Agreement incorporates all the elements of our discussions. If you agree to the

above, please sign each copy and return one to us thereby making the contents

legally binding on all of us.

This letter Agreement shall be

governed by English law and the signatories hereto agree to submit to the

exclusive jurisdiction of the English Courts in case of any dispute.”

59.

It was signed by the Claimant and both Defendants. There is no

indication that the parties were acting other than in their personal

capacities.

(ix) Sale of the Club

60.

An approach was made to the Defendants in November 2013 by Mr Roland

Duchatelet with an expression of interest in purchasing the Club. Mr Duchatelet

is a Belgian national who already owned a number of European football Clubs.

Negotiations were handled by Michael Slater and Max Deeley and progressed with

rapidity. On the 17th December 2013 a Share Purchase Agreement

relating to the acquisition of shares in Baton 2010 Limited was agreed (see the

corporate ownership and control diagram at paragraph [28] above). There was an

intended completion date by 2nd January 2014. It is apparent from

the documentation before the court that, whilst Mr Duchatelet was interested in

the potential Greenwich Peninsula development, it was not an imperative

for him. As Mr Deeley put it in his witness statement, Mr Duchatelet “was

not fixated on it”.

61.

It is also clear from the written and oral evidence that there was a

divergence of view between the Defendants and others acting for the Club as to

the extent to which they could pressurise Mr Duchatelet into acquiring some

form of an interest in the Greenwich Peninsula development as part of an

agreement to sell the Club (i.e. a Land Deal). The view of those negotiating

directly with Mr Duchatelet, and in particular Michael Slater, was that this

would be counter-productive. So far as Mr Duchatelet was concerned, the Valley

was the stadium that the Club owned and would, on any view, be using for a

number of years, even assuming the construction of a new structure within the Greenwich

Peninsula development site. Mr Duchatelet was clear that acquisition of the Club

had to occur prior to the conclusion of the January 2014 transfer window. There

was therefore no time to consider complex property deals. To the extent that

there was any serious value in the Greenwich Peninsula development project, it

was something which could be addressed in the fullness of time. The view was

that Mr Duchatelet might respond to additional pressure to conclude a side

agreement i.e. (the Land Deal) by walking away completely.

62.

An exchange of emails between Tony Jimenez and Michael Slater shows just

how fractious their relationship became over this issue. Mr Slater was,

manifestly, not an enthusiast of a strategy of selling the Club only

with a Land Deal. The exchange provides context to the possible reasons why, in

the Side Letter, the Defendants represented (falsely) that they were majority

shareholders. Had Mr Slater been identified as a significant shareholder then

the picture presented to Mr Khakshouri would have been very different. It was

not suggested to Mr Khakshouri during the trial that, had it been presented to

him that Mr Slater was a substantial minority shareholder, and had Mr

Khakshouri then contacted Mr Slater, the Claimant would have obtained from him

any reassurance that a Land Deal could be guaranteed. The exchange is also

significant because it highlights an important factual reality, namely that, if

the Club was sold without a Land Deal, then the prospect of the Defendants

being able to retain locus after the sale “skin in the game” was remote.

It also highlights just how serious and acute the Club’s finances were at the

time:-

i)

Email 27/12/2013 (23:21:06) Kevin Cash to Max Deeley and Tony Jimenez: “Gents,

Tony and I had a chat this evening regarding the Greenwich peninsula deal. We

are worried that if we leave the agreement of this to after completion there is

a chance that it might not fall our way. He will be totally in the driving seat

and could dismiss any of our proposals. We need to address this now and we need

to decide who and how this conversation takes place. Michael Max you have the

dialogue with Roland so I think you’re best placed to suggest the approach.

Ideas thoughts please.”

ii)

28/12/2013 (14:20:01): Michael Slater to Kevin Cash and Tony Jimenez

with Max Deeley cc’d: “Given that Tony is denying that I had a conversation

with him in the hotel bar on Tuesday 17th to the effect that we

would deal with the Peninsula after completion because Roland wasn’t interested

in dealing with it that day, I feel compelled to give advice in writing so

there are no misunderstandings. If Roland walks away because we side track him

regarding the Peninsula, nobody is going to point their finger at me. Roland

isn’t interested in the Peninsula. He wouldn’t want to move. He made that clear

on 17th. He’s perfectly happy with the Valley and showed much more

interest in the previous planning consents to develop the ground. Max tells me

he said the same thing during an earlier telephone conversation. So we took the

view that the best thing to do was to exchange and get the deposit. I am 100%

sure that we did the right thing. How else would we have put money into the

club and Les Bordes this month. Having met and spoken to Roland many times now

I have a decent idea as to what he’s like. He will do a deal with us in

relation to the Peninsula on 31st January just as easily as 31st

December. Raising it now distracts him and us from the main challenge- RBS. In

any event, nobody but Max should try to deal with him regarding the Peninsula. I think it would be a big mistake to push this before completion. We’ve already

lost at least one (much bigger) deal because of things being said to buyers. We

can’t afford to lose this one.

iii)

28/12/2013 (14:40); Tony Jimenez to Michael Slater: “I have no such

recollection as to the conversation you say happened and neither does Kevin.

It’s somewhat odd that if I did, I would call you having already texted you

yesterday and specifically ask you to make sure it featured in the deal on completion.

My recollection was that it would be dealt with between exchange and

completion. You also both received an email from Graeme where this featured and

you have yet to reply to him on any of the matters raised. I immediately

called Kevin straight after our chat given that I didn’t agree with the

approach you were suggesting. I would have done that last week, let’s put it

down to lost in translation, but I feel very strongly that we should push for

this now. For the record, I believe we are in a much better position to agree

this property deal before Thursday when we have leverage and still in control

than once we have sold out and Roland has Richard Murray, The Community Trust

and potentially others suggesting other advice to him. If you don’t feel like this

should be raised by you or Max, as you clearly don’t, then we will need to

consider who else should. Thank you for the advice you’ve set out but we are at

liberty to take it or not, or try ourselves given that we are not prepared to

leave this to chance. This is a massive aspect of the deal for us and we don’t

believe it should be left for a discussion down the road. He may not even agree

to meet after completion. If he’s not at all bothered about it why would he care

now or in Jan about agreeing to entering into this? Your line earlier to me is

he won’t agree to anything on the peninsula now- well why would he later? Far

more chance now. So please let us have your comments as to how we achieve out

objectives and who should go into bat on that front.”

iv)

28/12/2013 (14:59:48) Michael Slater to Tony Jimenez, (Kevin Cash, Max

Deeley and Graeme Muir cc’d): “Tony, Your recollection (as you explained it

to me earlier) is that we did have this conversation but it was over the phone

yesterday. We didn’t. You don’t have a recollection. I do and mine couldn’t be

clearer. You haven’t met or spoken to Roland. Max and I have. It’s the middle

of the night in Sydney, so I don’t expect to have Max’s input for a few hours

but I would be amazed if his view was radically different to mine. You seem to

be assuming that we haven’t tried to put this onto the table. We have. He said

“no”. Anyone other than Max dealing with this now would be madness. Any deal

we tried to put in place now would (a) in effect be an agreement with

ourselves and (b) would most likely be so vague as to be unenforceable. Think

back to the WMG deal. To pursue in a meaningful way Max would have to persuade

him to vary the SPA to require him to grant us an option on the Valley. It will

never happen before 2nd January. We’re trying to remove hurdles not

put up new ones.”

v)

28/12/2013 (14:47) Tony Jimenez to Michael Slater: “Michael, Ben

Kensall issued an email earlier this morning about the press release in The

Daily Mail and the speculation I specifically replied to that saying we shouldn’t

respond until the deal was completed. You were copied into this email and yet

you have done this without consulting me. In future DO NOT issue any press

releases without running them past me !!!”

vi)

28/12/013 (14:57:35) Michael Slater to Max Deeley and Kevin Cash: “Kev,

You’re the only one he’ll listen to. Have a word asap please because he really

won’t like the next thing I say to him. We’re in a china shop. We don’t want to

let a bull in.”

vii)

28/12/2013 (15:01:24): Michael Slater to Tony Jimenez (Max Deeley and

Kevin Cash, Graeme Muir cc’d): “Tony, I don’t act for you”

viii)

28/12/2013 (15:45:42): Tony Jimenez to Michael Slater, Max Deeley and

Kevin Cash, Graeme Muir cc’d): “Michael, Do not issue anything without my

agreement at the football club again. You didn’t have any permission from Kevin

or I in this regard. You are behaving like a method actor who has believed the

role he is playing. If you don’t act for me then supply those who do with what

we’ve asked for immediately otherwise I shall be dealing with this by

instructing lawyers on Monday.”

ix)

30/12/2013 09:00: Michael Slater to Graeme Muir: “Graeme, The reason

you haven’t heard from us is because we’ve been very busy. I won’t bore you

with the details. I attach the SPA. After the celebratory drinks and

backslapping on 17th I’m puzzled by the implication that Tony may

not be satisfied and may scupper this deal by refusing to complete. Let’s not

forget that the only reason we avoided admin this month (and were able to

provide essential funds to Les Bordes) was because we exchanged and were able

to use the buyer’s deposit. Also let’s not forget that loads of people have

tried to sell the club but until now all attempts have failed. Incidentally

the fact that Tony isn’t personally guaranteeing the warranties in the SPA (as

he agreed to do on the WMG deal) isn’t a mistake. It’s the deal Max and I

negotiated. Warranty claims can only be made against the seller, a BVI SPV.

Also, there was no requirement for the deposit to be held by the solicitors

until completion. Hard to believe isn’t it? That’s how good this deal is for

the seller. There will be adjustments between the seller and RM over the

proceeds because he is owed £600k, although I’m pretty sure he will write off

£250k and only require a £100k adjustment on completion. Again, another really

good deal. I trust you’ll forgive me but I now need to focus on negotiating

with RBS which will probably then involve Max and me re-negotiating with the

buyer. This is of paramount importance.”

x)

30/12/2013 10:31: Graeme Muir to Michael Slater: “As far as

completion is concerned, Tony is as keen to complete as anyone. If you note my

words, I state that completion will not take place until Tony is satisfied with

the documentation- it is not unreasonable that Tony (as a major shareholder) is

happy with what is being entered into. Had he been provided with all the

documents earlier and been kept informed on a regular basis by you, we would

not be discussing this. I cannot see why there is any reluctance on your part

for disclosure. As you are aware, there are a number of issues that need to be

dealt with prior to completion. These also affect you- including ensuring that

all principals are protected in terms of their tax position regardless of their

jurisdiction. I have also been informed that there is an outstanding issue

regarding the Dutch tax authorities, which Tony wrote to you about on 23rd

December regarding a player at the Club. He has not had a reply. Please confirm

that this is a matter for the previous owner- Richard Murray- as it relates to

a time before Tony and Kevin bought the Club (2008). You will agree that

$129,000 is not an insignificant amount and needs to be dealt with. What is the

status on this? Was this taken into account when discussing what RM is owed?

Well done on the negotiations regarding the deposit and warranties, although

these are matters that Tony should have been informed about at the time, if not

before. Please ensure that all matters and correspondence from now on is copied

to Tony and I. Please advice Teacher Stearn to do the same. On that note (and

given the work you have been doing over the last few days), please can we have

an update when you can on where we are with RBS, etc. I would like to speak to

you later this afternoon when you have had your negotiations with RBS.”

(x) Post-Sale discussions about the stadium

relocation

63.

The sale to Mr Duchatelet completed on 3rd January 2014. The

sale was not linked to a Land Deal. Following completion discussions continued

with Mr Duchatelet to see if he remained interested in the “stadium swap”. A

meeting occurred between Mr Deeley, Mr Slater and Mr Duchatelet on 23rd

January 2014. For whatever reason, interest on the part of Mr Duchatelet

petered out. It had become clear by March 2014 that matters were not

progressing, and were unlikely to in the future. Standing back, and as a matter

of commercial common sense, it is hard to see why Mr Duchatelet would ever have

been interested in bringing the Defendants back into the fold after the Club

had been sold to him without a Land Deal. If there was to be some future

benefit in the Club participating in the Greenwich Peninsula development, then

Mr Duchatelet was capable of exploiting that opportunity for himself and without

the Defendants. Indeed Mr Cash and Mr Jimenez well understood this to be the

case as the email exchange set out at paragraph [62] above demonstrates.

(xi) Post-sale discussion

between the Claimant and the Defendants

64.

Mr Khakshouri states that on 7th January 2014 he received a

text message from Mr Jimenez that informed him that “the deal has been

signed, completed and announced but the football authorities haven’t rubber

stamped it yet…” The monies were due to “drop in” tomorrow. Mr

Jimenez explained that Roland Duchatelet was “completely straight and

professional and when he says we are done then we really are. It has been so

refreshing having someone like him at the end after all these time wasters.”

The text message from Mr Jimenez did not explain that no Land Deal had been

completed. Mr Khakshouri assumed that the sale of the Club had included a

Land Deal, just as Mr Jimenez had promised it would.

65.

Mr Khakshouri spoke with Mr Jimenez on the phone on 19th

January 2014, during which Mr Jimenez informed him that he planned to repay

only $2m of the Loan, even though the terms of the Loan provided the Loan would

be paid on the earlier of 31st December 2013 and the sale of the Club.

Mr Jimenez explained that he could only repay $2m as 40% of the proceeds of the

sale of the Club were deferred until May 2014 and a significant portion of the

residual 60% had to be allocated to redemption of the mortgage. He added that

the deferred payment in May 2014 would be further reduced if the Club was

relegated. He asked Mr Khakshouri to agree to the variation of the terms of the

Loan.

66.

In paragraph 63 of his witness statement Mr Khakshouri stated the

following about this conversation. His oral evidence was to the same effect:

“63. Tony then said that Mr Duchatelet was not interested in

“participating” in the Land Deal so that we had effectively “inherited” 100% of

the Land Deal to use his words. All we needed to do was to provide the Club

with a new stadium via the land deal. Tony made out that this was an incredible

coup. I of course was delighted. The clear implication in what he was telling

me was that the Land Deal was proceeding following the sale of the Club and

that the only thing which had changed was that we stood to take a 100% interest

in the Land Deal rather than the 50% previously indicated (with Blackstone).

What he did not tell me was (as I now know) that the sale of the Club had made

no provision for the Land Deal at all, as Mr Duchatelet was not at that time

(or indeed thereafter) interested in moving from the club’s current ground at

the Valley Stadium to the Greenwich Peninsula. I had no idea that the

defendants had decided not to make the Land Deal any part of the sale of the

club, as Tony had promised me they would, and he was in this call content to

give me the clear impression that the Land Deal had been part of the sale of

the club and so was very much on foot.”

67.

On 20th January 2014, the Claimant sent an email to Mr

Jimenez stating:

“Needless to say, I’m very happy

that you were successful in the timely sale of Charlton Athletic FC and that

you are in a position to be repaying me. I am also very appreciative and

thankful that you and Kevin included me in the “property deal” which you both

believe to have tremendous potential.”

68.

The £2m part repayment of the Loan was transferred into the Claimant’s

account on 22nd January 2014.

69.

On 5th February 2014 the Claimant signed a letter amending

the terms of the Loan.

70.

Subsequently there was a break in email communication between the

Claimant and First Defendant. Mr Khakshouri’s evidence was that there was no

need for communication because his approach was to permit the Defendants to “get

on with it” ie continue to work on their collective participation in the Greenwich

Peninsula development project.

71.

On 5th June 2014 the sum of $1,057,121.41 was paid to the

Claimant comprising the balance of the principal on the Loan and the accrued

interest to 2nd June 2014.

72.

On 21st June 2014 Tony Jimenez visited Los Angeles. On 24th

June 2014, he informed Mr Khakshouri that the Land Deal had not been secured

upon the sale of the Club. According to Mr Khakshouri Mr Jimenez explained that

the sale of the Club had happened extremely rapidly, the new owner was intent

on doing a deal “on the spot” and there was insufficient time for the

Land Deal to be concluded. Mr Khakshouri says that Mr Jimenez told him that the

Land Deal had been discussed and agreed. However, for a variety of reasons, no

Land Deal had been concluded and, although the deal was not “dead”,

there was no such deal “for the time being”. Mr Khakshouri explained

this was a “complete shock” to him. He asked Mr Jimenez how this had

come about. It was explained to him that the sale had been negotiated by Kevin

Cash’s professional team but that they had mishandled and mismanaged this important

part of the transaction. Mr Jimenez said Mr Khakshouri had no reason to be

upset or angry since his main objective and motive for lending the money to the

Club had been to help him and Kevin Cash out, because they were friends. The

transaction was “friendship based” and not “deal based”.

73.

According to Mr Khakshouri, Mr Jimenez suggested he speak to Kevin Cash.

A telephone conversation ensued on 17th July 2014. Mr Khakshouri

says that during that call Mr Cash acknowledged that, in order to be fair to

him, they needed to compensate him to take account of his lost opportunity. He

was asked to calculate the loss that he had suffered by pulling out of the LA

Deal in order to lend money to the Club. On 19th August 2014 the

Claimant informed Mr Cash that his losses were in the region of $2m and rising.

Mr Cash was “taken aback” by the figure. Mr Cash then explained to Mr

Khakshouri that, according to Mr Jimenez, the transaction was based essentially

upon the attractive interest rate attached to the Loan. The Land Deal was

nothing more than an “upside” for the Loan but had never been assured,

promised or guaranteed.

74.

There followed a series of increasingly acrimonious exchanges between

the Claimant and Defendants. In a text message exchange between Mr Jimenez and

the Claimant on 24th September 2014 Mr Khakshouri posed the clear

and unequivocal question to Mr Jimenez: “did you or did you not promise me a

land deal in exchange for the £3m that I gave you? That’s a yes or no answer”.

Mr Jimenez reply was “yes.” The full details of this exchange are set

out at paragraph [ 111] below.

D Deceit- First Representation: The Defendants had

majority control

75.

As set out in paragraph [7] above the Claimant alleges that 2 deceitful

representations were made. Mr Atkins for the Claimant stated that both had to

be established for Mr Khakshouri’s case to succeed. In the text below I

consider each representation separately.

(i) Did the First Defendant represent that he

and the Second Defendant were the majority shareholders in and controllers of the

Club?

76.

The first question concerns the allegation that the First Defendant

represented that he and the Second defendant were majority shareholders in and

controllers of the Club.

77.

In my judgment, the First Defendant, Mr Tony Jimenez, did

represent to the Claimant during the September 2013 meetings that he, along

with Mr Cash, were the majority shareholders in the Club. I thus find as a

fact that the representation was made. I make this finding upon the basis of

the high standard of proof required in fraud cases.

78.

Mr Leech QC (for the First Defendant) argued that I should pay attention

to the way in which the representation was pleaded by the Claimant. I do: Mr

Khakshouri pleaded that:

“Mr Jimenez said that he and Mr Cash were controllers of the

Club. Mr Jimenez said that he and Mr Cash controlled the Club by holding

indirect majority shareholdings in the companies which owned the business and

assets of the Club. Mr Jimenez also said that Mr Cash was able to keep his

interest in the Club opaque by holding his shares through a web of nominee

companies, each of which held less than 10% of the shares in the companies

which owned the business and assets of the Club."

(APOC, paragraph [4])

"The Defendants thus represented to the Claimant that

(i) they were the controllers of the Club and that, as such (ii)(a) it was

their intention to make the Land Deal a certainty (b) by ensuring that the Club

was not sold without it."

(APOC paragraph [7])

79.

The nub of the averment was, hence, that control over the Club was

vested in Tony Jimenez and Kevin Cash by virtue of their “holding indirect

majority shareholdings”.

80.

Mr Khakshouri’s evidence in Court was consistent with his pleaded case.

I set out below some illustrations from the answers he gave during cross examination

which reflected the clarity of his recollection:

(1) “Yes, he told me

that they were the legal owners, him and Kevin were the legal owners, and

that's how he assured me, or absolutely convinced me that the land deal would

be included in the sale.”

(2) “He categorically

stated that he was the legal owner, with Kevin, of the club. This is my word,

"control", yes, I used that word, but clearly what he stated to me on

those days in September was that he and Kevin were the legal owners of the

club.”

(3) “There were two key

elements: one, that he and Kevin owned the football club, and two, that he was

not going to sell the football club unless it included the land deal. So I'm

very clear about that and he very much promised and in no uncertain terms

absolutely told me that the sale would not be made unless it included the land

deal.”

(4) “I remember this detail is because Tony took the

time to explain how Kevin was actually holding his interest in the club through

a series of, you know, majority shareholdings, and, you know, indirect majority

shareholdings in the club, all less than 10 per cent.”

(5) “We were talking

about who the owners were and who controlled the club and who the owners were,

and the legal owners, the way he explained it to me was he and Kevin were the

legal owners, and that Kevin's shares were somehow in these less than 10 per

cent shareholdings and in the club.”

(6) “Q. So that's the

expression he used? He said that he and Kevin were the legal owners of the

club and controllers of the club?

A. “Yes. And the

majority shareholders.

Q. “Well it's not the

same thing, is it, to be the majority shareholders? You don't say

"majority shareholders" in this paragraph, do you?

A. “Well, I recall that

he did tell me that they were the majority shareholders and that was reflected

in the side letter which confirmed it to me.”

(7) “When I asked him if

Kevin knew about the conversations that we were having, he again repeated that

they were the majority shareholders of the club.”

(8) “I recall that he

did say they were the owners, that was for sure. As far as majority

shareholders, I -- I'm sure that that was also told to me and it was certainly

stated in the side letter, but to me it -- yes, that's -- you know, I took them

to be the owners of the football club, the legal owners of the football club.”

(9) “It was critical

because, like I say, I had two things to work on: that they did have the

control of the club and that they were not going to sell the club unless it

included the land deal. Those were the two pivotal, absolutely key elements to

why I loaned the money.”

(10) “And Tony had assured

me, as owner, and he and Kevin being the owners, they would be able to ensure

that the club wasn't sold without the land deal in place.”

81.

In oral evidence Mr Jimenez (in contrast to Mr Khakshouri) said the

following, about his recollection of events:

“I don’t remember speaking to him about … you see, this is

when it clouds for me. Darius’s recollection of what was said at specific

times, my memory isn’t that good. I can’t remember whether I spoke to him on 15th,

the 16th or the 17th about which items, because I saw a

lot of him. So for me to be specific, I would have to sort of embrace it

across a number of days rather than say I just spoke about that during that

dinner, and something else the next day. Unfortunately I haven’t got such a

clear memory of what happened four years ago.”

He accepted that in answering

questions he was trying to work out what he would have said, but he did not

recall what he had actually said at the time. In response to a question

from the Court to Mr Jimenez asking him whether he was: “…trying to work out

now what probably happened,” he responded “yes”. It is an obvious

point to make but any judge tasked with evaluating the weight to be attached to

oral evidence will be astute to the possibility that a witness, in the

pressured crucible of a court, will fashion his answers to fit his legal case,

consciously or unconsciously. And that risk is all the greater when the witness

acknowledges that in giving his evidence he is trying to work out and

reconstruct – some years later - what he would have said, and not simply

recollecting from memory what he did say.

82.

I am bound to accept Mr Khakshouri’s account. I find that the First Defendant

did make the representation alleged. There are six reasons for this.

83.

First, in choosing between the competing versions of the Los

Angeles discussions between 15th - 17th September 2013

I must accept the account of Mr Khakshouri. He was cross-examined for just

short of two court days. He was a calm and thoughtful witness throughout. He

gave an unwaveringly consistent account of events. He had a detailed

recollection and memory of what occurred during the meetings. He was described

by other witnesses (for the Defendants) as “meticulous” in his attention

to detail, a fact which was evident from many documents before the Court. He

demonstrated a command of the details of the documents. He did not seek to

argue around difficult points but accepted several propositions put to him

which were not entirely in his favour. His account was balanced. His version

of events, moreover, was consistent with both the documentary evidence and the

essential logic and commercial realities behind the case. To use the

vernacular his case “stacked up”. So far as Mr Jimenez was concerned,

he accepted, as set out above, that his memory of the details of the September

meetings was hazy. He had no clear recollection of who said what, where and

when. His answers to questions were, as he acknowledged, his attempt, some

years later, to work out what he would have said and his ability to answer

questions about specific documents or aspects of the financing of the sale of

the Club was often imprecise. In a number of critical respects (as I explain

in below), I also found his answers to be most unsatisfactory.

84.

Second, the account of Mr Jimenez changed significantly over the

course of the proceedings, and in particular from the early days of the litigation

when he denied making any representation at all about control (when his

memory should have been sharpest) to the later stages of the litigation when he

suddenly accepted that he did in fact make a representation about

control (but when on his own account his memory was at its least reliable).

In paragraph 11(5) of his Amended Defence Mr Jimenez explained that he had no

beneficial interest or direct or indirect shareholding in the Club (paragraph

[3]) and he denied representing “…he and Mr Cash controlled the club or that

… Mr Cash had an interest in the club”. Following disclosure, the Claimant

sought further and better particulars of the First Defendant’s averment in the

light of both the Side Letter and a letter from his solicitors which implied

that prior to the sale of the Club Mr Jimenez did exercise control (see

paragraph [89] below). Mr Jimenez responded (29th July 2016) saying

that the Side Letter was incorrect and the solicitor’s letter was “imprecise

and informal”. In his witness statement (4th August 2017) Mr

Jimenez again denied having told Mr Khakshouri that he and Kevin Cash were the

controllers of the Club, though he does state that he believed that Mr

Khakshouri would have been aware that “we effectively controlled the Club”.

85.

Under cross-examination Mr Jimenez changed his position. He now accepted

that the question of control was “for sure” material to Mr Khakshouri’s

decision to make the Loan. He was interested in control because “…Darius

would have wanted to know that he was going to get his money back”. He

accepts that he gave that assurance by reference to control. Mr Khakshouri says

that the need for clarity over legal ownership was because he needed certainty that

a linked Land Deal could be secured on sale of the Club. He did not accept that

the need for certainty over control was related to the repayment of the Loan.

But it suffices, for present purposes, that Mr Jimenez accepted that there was

a powerful reason for him to satisfy Mr Khakshouri about the control structure

and it follows that for both parties legal control / ownership was

an issue. Mr Jimenez’s evidence has thus been inconsistent on this key issue

throughout the litigation. By contrast Mr Khakshouri’s evidence has been wholly

consistent, to the point whereby Mr Leech QC accused him of having a “mantra”

which he kept repeating. If it was a mantra then it was because he was asked,

repeatedly, more or less the same question, to which he gave the same reply. A

mantra can simply be the truth consistently reiterated.

86.

Third, compelling corroborative evidence is found in the Side

Letter (see paragraph [28] above). This was drafted for the Defendants by

their own employees and colleagues upon the express basis that it accurately

reflected the discussions which had occurred between Mr Khakshouri and Mr

Jimenez during the September 2013 meetings. In it both Mr Jimenez and Mr Cash represent,

as fact, that they were the majority shareholders in the Club. These

express representations are consistent with the evidence of Mr Khakshouri. For

Mr Jimenez’s alternative version of events to be accepted: (a) I must find

that four senior executives on the Defendant’s side of the Court room (Messrs

Muir, Deeley, Cash and Jimenez), all of whom knew better, made a simple yet

glaring error when they (variously) drafted, approved and signed the Side

Letter; (b) once I have discounted and ignored the Side Letter I must then

proceed to prefer the account of a witness who on his own acknowledgement has a

serious difficulty in recalling what he actually said and what was said to him;

(c) I should then accept Mr Jimenez’s version of what he thinks he said

even though his account from the witness box was at variance with his position in

pleadings and in his witness statement, all signed by him; and (d), I must also

reject the consistently advanced account of a witness (Mr Khakshouri) whose

evidence was cogent and consistent with the underlying logic of the case and

with the documents. Viewed thus I do not find the First Defendant’s evidence

remotely convincing.

87.

Fourth, Mr Khakshouri’s evidence makes commercial sense. The

Side Letter makes it expressly clear that the Loan was in consideration for the

Land Deal. If the Land Deal was to be delivered, it is entirely credible that Mr

Khakshouri would have asked Tony Jimenez to guarantee to him how he was

to bring it about. If the answer had been merely “I will do my best but no

promises …” then that is a very far cry from “I promise to you that I

will ensure the coming into being of the Land Deal by refusing to sell the Club

without a Land Deal being in place”. Counsel for the Defendants argued that

there was very little between the parties and it was a question of “nuances”

only. I disagree. Even on the Defendant’s own best endeavours only case, they

were seeking to secure a sale of the Club simultaneous with securing

participation in a Land Deal which would survive the sale. They proposed to do

this through the joint SPV structure described at paragraph [44] above. I have

also set out above (paragraph [62]) the email exchange during which Kevin Cash

and Tony Jimenez both expressed the view that without a linked sale (the Land

Deal) they had no leverage at all. And they were right. For the Defendants to

remain “with skin in the game” (as it was put) they simply had to have

an agreement in place which outlived the sale of the Club. And they could only

do this through a linked Land Deal. There is also evidence before the court which

shows that as of September 2013 the Defendants were extremely confident that

they would secure a linked sale, i.e. a Land Deal (see eg the duration

of the evidence of Michael Slater set out at paragraph [114] below). It stands

to reason that Tony Jimenez would have been confident in putting to Darius

Khakshouri that he (and Kevin Cash) had the legal power to ensure that

the Club would not be sold absent a linked Land Deal. There was a sound

commercial reason why the first representation would be made, even on the

Defendant’s own case.

88.

Fifth, the identification of Messrs Jimenez and Cash as the

majority shareholders, and not anyone else, was also critical. The short

point is that a representation that it was Messrs Jimenez and Cash who jointly legally

controlled the Club was, in my judgment, the sole permutation of legal

ownership that would have satisfied the Claimant and induced him to make the Loan.

Had the representation been that other natural or legal persons or

entities (for example Mr Slater and/or the Cavansa Trust and/or a slew of

unknown Spanish minority shareholders) were in legal control of the Club then

the all-important personal dynamic would have evaporated from the equation.

There is a plethora of evidence to support this proposition. Mr Jimenez in his

witness statement said: “… our discussion about the loan was informal and

relaxed, it was a discussion between close friends, with Darius eager to help

and support. It was not like a business negotiation – Darius’s attitude was that

he was happy to provide whatever we needed, as he trusted Kevin and me totally”.

He repeated as much in oral evidence, as did Mr Cash. Mr Khakshouri also

considered trust to be pivotal. He was being invited to raise funds and lend

them on (more or less) 48 hours notice, with no documentation, and he did so because

of his personal relationship with the Defendants and their stated ability to

control the Club via their joint majority shareholdings. Mr Khakshouri

made this clear on multiple occasions in his evidence. For instance:

(1) “I was committed to

this project, the project being the land deal, the land deal being that, you

know, originating from the fact that the club wouldn't be sold without it, and

the people that could make that possible were the owners. The owners were Tony

and Kevin. So everything was, in my mind, lined up the way it should have

been, and so now we're generating paperwork and it's after the fact and I still

don't bring in an attorney and try to change anything because I trusted and

believed that we were all working towards that same goal.”

(1) “I was committed to

this project, the project being the land deal, the land deal being that, you

know, originating from the fact that the club wouldn't be sold without it, and

the people that could make that possible were the owners. The owners were Tony

and Kevin. So everything was, in my mind, lined up the way it should have

been, and so now we're generating paperwork and it's after the fact and I still

don't bring in an attorney and try to change anything because I trusted and

believed that we were all working towards that same goal.”

(2) “Yes, I asked him "Who is the owner of --

how is the club owned?" and he was very specific in telling me that, you

know, he and Kevin owned the football club. There wasn't anybody else involved

in this. I needed to know that I was loaning this money to Kevin and Tony, and

that there was nobody else involved and that it was -- that had to be very

clear in my mind because there was very little time. Very little time and no

documentation.”

(3) “That was part of it, but also I wanted to make

sure that, you know, Tony was telling me exactly -- when he was telling me that

they were the owners I was sure that that would be the same thing that I would

hear back from Kevin Cash if I needed to confirm that.”

I accept the evidence of Mr

Khakshouri.

89.

Sixth, it is also relevant that the Defendants repeated or made,

or at the least authorised the making or repetition of, similar

representations, including to third parties. The representations were that

either they collectively or Tony Jimenez on his own were majority shareholders

or owners. The following are contemporaneous illustrations:

i.

In July 2013 both Defendants were copied in on an email drafted by Mr

Deeley to a prospective purchaser of the Club which said that the First

Defendant “…owns 90% of Charlton Athletic” as he is “…the majority Shareholder

at Charlton Athletic controlling 90% of the share capital.” The

representation as to ownership was quite plainly false. This was just two

months prior to the meetings in September 2013 in Los Angeles.

ii.

In addition, there is an email from Mr Cash to Mr Jimenez and to Mr

Deeley in December 2013 which contains suggested answers to questions from a

potential purchaser of the Club which also states, again inaccurately, that the

First Defendant is the 90% controller of the Club.

iii.

In addition there is an email from the Defendant’s solicitor to the

Claimant sent on 30th January 2014 (after the sale of the Club) explaining

that the reason for switching the borrower on the Loan was that the Defendants

(i.e. Mr Jimenez and Mr Cash) “…no longer control” the Club. The clear

implication intended to be drawn was that Mr Jimenez and Mr Cash had been the

controllers, but were no longer.

iv.

This position was repeated subsequently in a letter from the Defendants

themselves to the Claimant’s solicitors dated 31st July 2015 where

the Defendants explained that the switch in the borrower was again because “we

no longer controlled” the Club.

(ii) Was the representation false?

90.

I turn now to the second question: Was the representation about majority

control false? The answer is that the representation was false. This

is now common ground between the parties. Neither Mr Jimenez nor Mr Cash are

shareholders at all. This is clear from the diagram at paragraph [28]. The

true position can be summarised very shortly.

91.

Mr Jimenez is one of more than 20 beneficiaries in the Cavansa Trust.

He is not employed by the trust and nor does he have any formal power of