Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

England and Wales High Court (King's Bench Division) Decisions

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> England and Wales High Court (King's Bench Division) Decisions >> Glaser & Anor v Atay [2023] EWHC 2539 (KB) (12 October 2023)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/KB/2023/2539.html

Cite as: [2024] PNLR 8, [2023] Costs LR 1847, [2024] 1 WLR 1733, [2023] EWHC 2539 (KB), [2024] 3 All ER 319, [2024] 1 FLR 1115, [2024] WLR 1733, [2023] WLR(D) 417

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [View ICLR summary: [2023] WLR(D) 417] [Buy ICLR report: [2024] 1 WLR 1733] [Help]

KING'S BENCH DIVISION

BRISTOL APPEAL CENTRE

ON APPEAL FROM WINCHESTER COUNTY COURT

His Honour Judge Berkley

(Claim No: G74YJ072)

Strand, London, WC2A 2LL |

||

B e f o r e :

____________________

| (1) MICHAEL GLASER KC (2) VICTORIA MILLER |

Claimants/Respondents |

|

| - and - |

||

| KATHARINE JANE ATAY |

Defendant/Appellant |

____________________

for the Claimants/Respondents

Jacqueline Perry KC and Alexander Bunzl (instructed by Direct Access)

for the Defendant/Appellant

Hearing date: 25 July 2023

____________________

Crown Copyright ©

- This case concerns two barristers, the claimants, suing a former client, the defendant, for payment of outstanding fees under the terms of a written agreement entered into under the Public Access Scheme. The matter now comes before this court in the form of an appeal and cross appeal against the decision of His Honour Judge Berkley of 6 December 2022. For reasons of convenience and consistency, I will continue to refer to the parties as claimants and defendant respectively.

- The central issues are:

- The defendant contended below that the application of the 2015 Act meant that the claimants were entitled to nothing. The claimants argued that the 2015 Act did not apply and, even if it did, they were nevertheless entitled to payment in full.

- In the event, the Judge held that the operation of the 2015 Act did indeed preclude the claimants from relying on the contractual term relating to payment but that the defendant should nevertheless pay 70% of what would otherwise be the contractual sum due by way of quantum meruit. The defendant seeks to challenge this decision on appeal and the claimants cross appeal. The primary stance of each therefore remains that this is an all or nothing case in their favour.

- The defendant was pursuing a financial remedy in proceedings against her former husband, a wealthy businessman. It has been estimated that the value of the assets at stake was in the region of £20M.

- She engaged the first and second claimants to act on her behalf in the litigation on a public access basis as leading and junior counsel respectively. For the sake of clarity, I will not elaborate upon the details of the procedural history of the case save to the extent that they are material to the issues which arise on this appeal. Nor shall I engage with some of the issues with which the Judge below had to grapple because permission to appeal on such issues was refused and my permission was not sought to revive them.

- In March 2020, the trial was listed to be heard over a ten day period starting on 21 September 2020. The hearing, which had originally been given an optimistic time estimate of five days, had already been listed and adjourned once before.

- By a letter dated 29 June 2020, the first claimant set out the terms under which he was prepared to accept the defendant's instructions. In so far as is material, it provided:

- The second claimant's terms were identical save that the level of fees was one half that of the first claimant.

- This was the basis upon which the defendant retained the claimants. The Judge below observed, in my view reasonably, that "given the significant sums involved one would have expected a more carefully thought through document".

- The Judge went on, at paragraph 14 of his judgment, to note that the terms were "based on the Bar Standard Board's Templates".

- In their written submissions below the claimants had asserted:

- Indeed, when giving permission to appeal, the Single Judge expressed understandable concern about the potential impact which the determination of the issues between the parties to this appeal might have upon the enforceability of any contract based upon the BSB model.

- However, it is to be noted that the BSB templates, in fact, include the following:

- Counsel for the claimants rightly conceded before the Judge that, in the claimants' terms, the obligation to pay non-recoverable fees in advance was "in addition" to those contemplated in the BSB standard letter. Of course, this point is not determinative of the issues before me but it is important to bear in mind that that my findings are therefore not to be taken either as an endorsement or condemnation of the BSB terms.

- In the event, at a hearing of 26 August 2020, Mr Atay applied to adjourn the trial. He was successful. Shortly after, on 31 August, the day upon which the bulk of counsels' fees became due under the terms of the letter, the defendant sent an email to the claimants' clerk indicating that she no longer wished to instruct them. She had made the first and second payments but refused to pay any more.

- The claimants duly commenced proceedings against the defendant seeking recovery of the balance of their fees under the contracts described above at paragraph 10, as well as payment of other fees which remained unpaid under further contracts concluded between themselves and the defendant on 25 August 2020.

- The defence raised issues of professional negligence which were promptly struck out and thus require no further consideration on this appeal. The only questions upon which this court must adjudicate relate, therefore, to the impact, if any, of the 2015 Act upon the rights and obligations of the parties.

- The term upon which the Judge concentrated his attention in this regard is the stipulation in the letter of instruction that:

- In summary, the defendant complains that this term is unfair because, in the event of the trial not going ahead, it had the potential to entitle the claimants to claim a lot of money for doing little or nothing. The defendant further sought to argue that the term relating to the price was parasitic upon the survival of the payment term and they should both fall together. I reject this latter contention for reasons set out later in this judgment.

- Before embarking upon a consideration of the impact of the statutory regime, it may be useful to consider briefly the position between the parties at common law.

- It is now over twenty years since the old rule preventing barristers from suing for their fees was abrogated. As a result, the terms of any retainer now fall, at least for the most part, to be approached in the same way as any other contract for services.

- In the context of this case, it is important to bear in mind that the claim is one in debt and not breach of contract. As the authors of Chitty on Contracts 34th Edition observe at 24-038:

- Under the terms of a contract for services, the general rule is that they are to be paid for as and when rendered. However, it is open to the parties to stipulate for prepayment of part or all of the price. Where this is so, an action for the price lies as soon as the date for payment has arrived. As Lord Alverstone CJ observed in Workman Clark & Co Ltd v Lloyd Brazileno [1908] 1 KB 968:

- The common law position is, however, rendered far less straightforward by the application of the statutory regime for the protection of consumers.

- The statutory control of unfair terms in contracts was first introduced in the form of the Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977. The protection to be afforded to consumers was thereafter extended by the Unfair Contract Terms in Consumer Contracts Regulations 1994 and 1999. The 2015 Act, which came into force on 1 October 2015, now provides the principal basis upon which the fairness of terms found in contracts between consumers and traders fall to be assessed. The 1977 Act no longer has any application to consumer contracts and the 1994 and 1999 Regulations have been revoked.

- The Regulations and the 2015 Act were passed to give effect to a series of European Union Directives culminating in Directive 2011/83/EU. Over the years, there has thus accumulated a considerable body of relevant European jurisprudence. I note that CJEU rulings made after 1 January 2021 are not binding on the UK but may still provide useful interpretative guidance pursuant to s 6(2) of the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018. It is further to be noted that the terms of the 2015 Act, whilst adopting the central unfairness test to be found in the Directives, have deliberately gone beyond the minimum level of protection which they afford.

- The provisions relating to the control of unfair terms are to be found in Part 2 of the 2015 Act. By the operation of section 61, they apply to contracts between a trader and a customer. There is no dispute in this case, for present purposes, that the claimants are traders and the defendant is a customer. Accordingly, the contracts between them fall within the scope of Part 2.

- During the course of the hearing, criticism was raised by the claimants to the effect that the defendant's pleadings did not reflect in adequate detail the nature of her case under the 2015 Act. These criticisms were not devoid of merit. It is also clear, from paragraphs 38 – 43 of his judgment, that the Judge struggled to understand the legal basis which underpinned the defendant's counsel's presentation of the arguments both orally and in writing. Throughout the oral submissions before me there ran a thread of fitful but unhappy and mutual recrimination between the advocates upon which topic it would be disproportionate for me to dwell at any greater length in this judgment.

- In any event, s 71 of the 2015 Act provides:

- Section 62 of the 2015 Act provides, in so far as is relevant:

- However, s 62 does not apply to two categories of term as defined in s64:

- I note, in passing, that these safe harbour exceptions can only be relied upon if they are both transparent and prominent. However, the defendant takes no issue on transparency or prominence in this case and so I can move on.

- There is a further restriction on the applicability of the safe harbour protection to be found in s64(6) which provides:

- It is Part 1 of Schedule 2 which contains what is commonly referred to as the grey list. The consequence of any given term falling within the parameters of any one of the items on this list is that it cannot be treated as falling within the safe harbour exclusions and so must be subject to the scrutiny of the unfairness test. In Case C-478/99 Commission v Sweden (2002) ECR I-4147, the Court stated:

- The items on the list relied upon by the defendant provide:

- The defendants argue that when the claimant dispensed with their further services she was not deciding "not to conclude or perform the contract". The contract had already been concluded and all that remained was for the claimant to pay the debt. This could not usefully be categorised as a failure on her part to perform.

- However, this approach overlooks the fact that the relevant term must be analysed not on the basis of what actually transpired after the agreement but as at the time the contract was entered into. The performance required of the claimant at that stage was the payment of sums of money on or before the stipulated times. Accordingly, had the defendant, for example, given notice in unambiguous terms, even before the successful adjournment application, that she had no intention to pay any further sums then she would have been found to have been in anticipatory breach of contract. The defendants could then have opted to terminate the contract and claim the full fee whilst performing no work under the agreement and remaining available to take on any alternative work without giving credit for any mitigation of loss.

- The further question arises, however, as to whether the stipulation that the obligation to pay the fees gave rise to a contractual debt (rather than amounting, at common law, to a penalty for breach of contract) is sufficient to take the relevant term out of the grey list.

- In this regard, further reference may be made at this stage to the Competition and Markets Authority "Guidance on the unfair terms provisions in the Consumer Rights Act 2015" which provides:

- do not allow for cancellation within the 'tie-in' period, and thus bind the consumer who terminates to make all, or substantially all, the payments that would have been made had the contract remained in place; or

- allow for cancellation, but only on payment of a charge or fee equivalent to all, or substantially all, of the payments…

- In addition, the Explanatory Notes to the 2015 Act give the following illustration:

- In this case, the contract period for the performance of the claimants' services, as at the date of the agreement, was liable (and indeed likely) to extend to the expected date of conclusion of the trial. In contrast, the bulk of the fees were to be paid weeks in advance of the expected conclusion of the performance of the services to which they related. In substantial effect, they comprised a non-refundable 100% deposit. Returning to the wording of paragraph 5 of the grey list, it is helpful to strip out those words which are not material to the circumstances of this case:

- I consider it to be clear that this is indeed the effect of the relevant term in this case and it thus falls within the parameters of paragraph 5. The interpretative emphasis must be not upon the rigid categorisation of a liability as debt or damages for breach at common law but upon the practical effect. Otherwise an unscrupulous barrister could agree to accept instructions for appearing in a case not yet listed and almost bound to settle on condition that the entirety of what would otherwise be the brief fee and the entirety of the predicted daily refreshers were to be paid in a lump sum on a date months in advance of the notional hearing date.

- This does not mean that the term is automatically unfair but it does mean that it does not fall within the safe harbour exceptions.

- Although I have determined that, on a proper construction, the relevant term falls within the parameters of the grey list, I ought, for the sake of completeness, consider what the consequences would have been had I taken the opposite view.

- This involves considering whether the term falls within the parameters of the safe harbour. For convenience, I set out the relevant provisions of s. 64 again below:

- As the authors of Consumer and Trading Standards Law and Practice 11th edition observe at 9.55:

- In Bairstow Eves London Central Limited v Smith [2004] EWHC 263, decided under the equivalent provisions of the earlier regulatory framework, Gross J (as he then was) observed:

- In my view the core of the bargain was that the claimants' fees were £90,000 and £45,000 respectively for preparing for and representing the claimant at the hearing. Accordingly, it would not have been open to the defendant to seek to challenge before the courts the level of fees nor the nature and extent of the work involved in preparation for and appearance at trial.

- However, the term concerning the timing of payment and the consequences of the case not going ahead, although important, does, not in my view, fall within the parameters of s.64. On this issue, I find myself in respectful disagreement with the conclusions of the Judge below.

- Having determined that the relevant payment term fell within the grey list or, in any event, did not fall within the protection of s. 64, it is necessary to consider the question of fairness.

- The Bar Standards Board Guidance provides:

- You should take care to estimate accurately the likely time commitment and only take payment when you are satisfied that:

- If the amount of work required is unclear, you should consider staged payments rather than a fixed fee in advance.

- You should never accept an upfront fee in advance of considering whether it is appropriate for you to take the case and considering whether you will be able to undertake the work within a reasonable timescale.

- If the client can reasonably be expected to understand such an arrangement, you may agree that when the work has been done, you will pay the client any difference between that fixed fee and (if lower) the fee which has actually been earned based on the time spent, provided that it is clear that you will not hold the difference between the fixed fee and the fee which has been earned on trust for the client. That difference will not be client money if you can demonstrate that this was expressly agreed in writing, on clear terms understood by the client, and before payment of the fixed fee. You should also consider carefully whether such an arrangement is in the client's interest, taking into account the nature of the instructions, the client and whether the client fully understands the implications. Any abuse of an agreement to pay a fixed fee subject to reimbursement, the effect of which is that you receive more money than is reasonable for the case at the outset, will be considered to be holding client money and a breach of rC73. For this reason, you should take extreme care if contracting with a client in this way.

- In any case, rC22 requires you to confirm in writing the acceptance of any instructions and the terms or basis on which you are acting, including the basis of charging."

- This illustrates the fact that the prohibition on holding client's money does not preclude a barrister from entering into an agreement with the client providing for reimbursement of part of a fixed fee with reference to time actually spent.

- This factor is not, of course, determinative of the issue of unfairness but does demonstrate that is possible for a barrister to draft direct access terms which do not compel the consumer to pay up front for all services with no provision for reimbursement without encroaching on the principle that he or she should not hold client's money.

- Section 62(4) of the 2015 Act, it may be recalled, provides:

- In Director General of Fair Trading v First National Bank [2002] 1 AC 481 Lord Bingham observed at para 17:

- Section 62(5) of the 2015 Act provides:

- I am satisfied, after taking into account the matters referred to in section 62(5), that the term as to timing of payment and the consequences of the trial not going ahead created a significant imbalance in the parties' rights and obligations under the contract. In short, the claimants were entitled to be paid far in advance for two weeks' preparation and participation thereafter in a two week trial. Even if there had been no work done whatsoever, the fees would have remained payable and subject to no element of reimbursement at all. Counsel would thus be entitled to take on alternative remunerative work during the relevant period and any sums thus earned would not go towards reducing the liability of the defendant. I accept that it not always easy for counsel, particularly leading counsel, to find work at relatively short notice but it is by no means impossible.

- In contrast, the financial risk of the trial not proceeding was borne entirely by the defendant. In particular, there was provision for additional work to be charged at £500 per hour for leading counsel but with no abatement in the event that no work whatsoever actually was carried out. It is not suggested that the contractual sums had been reduced to reflect, in advance, the possibility that the trial may not go ahead as listed.

- As the Judge below put it, the relevant term is "an "all or nothing" term weighing 100% in favour of the barrister. Clearly the imbalance was to the detriment of the consumer. I agree with his reasoning on this issue.

- But for that term, the barristers would have been entitled at common law to payment of the fees upon conclusion of their performance.

- The issue of fair dealing in this case must take into account a number of features. Firstly, save for some enquiries from the defendant aimed at clarification, the terms reached between the parties were not the product of individual negotiation. The letter in which they are to be found is worded in the form of a fait accompli and the defendant, as will almost invariably be the case in direct access arrangements, was not separately legally advised. Secondly, the risks of any given trial being rendered ineffective are much more familiar to members of the legal profession than to lay clients. They would have known, for example, that the fact that a trial had already been adjourned once provided no assurance that it could not happen again. Thirdly, the means by which a direct access barrister could provide some means of reimbursement in the event of the trial not proceeding fell also (or ought to have fallen) within the knowledge of the claimants. Fourthly, as is the case in most litigation, and particularly family proceedings, the lay client is almost inevitably placed in a stressful, dependant and potentially vulnerable position. I do not overlook the fact that the claimants clearly considered the defendant to be a demanding and difficult client but this feature does little of nothing to redress the imbalance in the relationship between professional and lay client. One of the occupational hazards of direct access arrangements is that the absence of any instructing solicitor inevitably exposes counsel more acutely to the unfiltered, uncomfortable and persistent demands of the importunate client.

- I readily accept that the relevant term was clear and brought openly to the attention of the defendant but that is not a feature which is sufficient, of itself, to establish that the requirement of good faith has been fulfilled.

- I wish to make it plain that my adjudication on this issue is not to be taken as an imputation of professional impropriety whatsoever on the part of the claimants. Subjectively, they doubtless considered that there were sound commercial reasons to seek to protect themselves in clear terms against the risk of not being paid in full regardless of whatever procedural course the ligation might subsequently take and, in particular, against the adverse consequences of any and all potential threats to the viability of the trial. Had the other contracting party not been a consumer then the principle of freedom of contract would have readily permitted this. However, on an objective appraisal, the relevant term went significantly beyond what would have been consistent with good faith in the context of the aims and intentions of the statutory framework.

- S 62(1) of the 2015 Act provides: "An unfair term of a consumer contract is not binding on the consumer…"

- In my view, this precludes the claimants from relying on the so-called payment term. The level of fees provided for is thus preserved as is the scope of the work to be provided by way of consideration therefor.

- Notwithstanding this consequence, the claimants argued that they should be awarded a reasonable sum by way of quantum meruit or (with less enthusiasm) an implied term.

- The Judge below was persuaded to approach the issue on a quantum meruit basis but it does not appear that he was provided with a great deal of assistance either as to the appropriateness of a quantum meruit basis of assessment or as to the nature of any such assessment, if made. In giving permission to appeal, the Single Judge observed:

- In deciding that a quantum meruit approach was appropriate, the Judge referred to Chitty on Contract 34th Ed Chapter 32 and in particular 32-077 which provides:

- In this case, however, the scale of remuneration had been agreed. It was expressly set out in the claimants' letters and preserved intact by the safe harbour provisions of the 2015 Act. But once the claimants are precluded from relying upon the payment term, the contract falls to be treated as providing for a lump sum payment for the services of preparation and appearance at trial. The parties could have agreed a divisible contract but they did not.

- This background brings into focus the issue of partial performance of entire obligations which is addressed in Chitty at 24-029:

- A recent illustration of the operation of this rule is to be found in Barton v Jones [2023] AC 684 in which an agreement had been entered into to the effect that the claimant would be entitled to a substantial fee in the event that he introduced a buyer for the defendant's property in an agreed sum of £6.5m. A buyer was duly introduced but the sum he paid fell short of the contractual level agreed between the claimant and the defendant. The Supreme Court held that, on the express terms of the introduction agreement, the obligation accepted by the company was an obligation to pay the claimant a specified sum on the happening of a particular occurrence, namely the sale of the property for at least £6.5m to a buyer introduced by the claimant. There was no express term of the introduction agreement creating an obligation on the company to pay the claimant a fee in any other circumstances, including those in which a buyer should purchase the property for less than £6.5m.

- Of course, the original intention of the claimants in this case was that the entirety of the obligation should arise by way of their reserving their time and not by the actual preparation and appearance at trial but they cannot rely upon the term providing for this because it is unfair. By the operation of the statutory regime, an unfair term must be deemed never to have existed. Where a term is unfair, the whole of that term must be removed and not just the unfair aspects of that term. Otherwise this would amount to amending the term which would be impermissible (see Consumer and trading Standards Law and Practice at 9.121 and the cases therein referred to).

- In Dexia Nederland BV v XXX and Z Joined Cases C-229/19 and C-289/19 the First Chamber held:

- Even if it were otherwise permissible to apply a quantum meruit approach at common law it would, in my view, be precluded on the facts of this case by the operation of the statutory regime. The court in Dexia went on to hold:

- In short, if a quantum meruit approach were permissible in this case, it would have the potential to disincentivise traders from ensuring that the terms under which they contracted were fair. Otherwise they could opt to incorporate unfair terms in the hope that they would not be challenged but confident that there would be a safety net providing for the payment of a reasonable sum in the event that they were.

- For the sake of completeness, I will go on to consider, even if (contrary to my findings) a quantum meruit approach were permissible, whether or not there was sufficient material before the Judge below to make an assessment as to the level of payment which would follow.

- The Judge concluded that the claimants were entitled to "a reasonable fee" amounting to 70% of the contractually agreed fee. I can well understand his reluctance to reach a conclusion which would deprive the claimants of the entirely of their commercial rewards but there are several flaws to be found in his reasoning.

- His first error, in my view, was to assume that the defendant had acted in breach of contract and that this was a relevant matter when considering the quantum meruit issue.

- Once it has been determined that the term relating to the obligation upon the defendant to pay up front is one which the claimants were not entitled to rely upon by the operation of s62 of the 2015 Act then there was no remaining basis upon which it could be concluded that, by not making such a payment in advance and where the claimants' performance had been rendered impossible by the adjournment, the defendant was in default.

- Furthermore, there was nothing in the agreement which placed the defendant under any obligation to continue to instruct the claimants beyond the period covered by the terms set out in the claimants' letters. On the contrary, the letters provide that any further work would have to be the subject matter of a further agreement between the parties with no guarantees that the claimants would be willing to undertake any such work. They may well have been willing to negotiate some sort of reduction in future fees but there was no contractual obligation upon them to do so. In so far as is material to this appeal, the contractual obligations of the parties were expressly defined so as to apply to the preparation of and representation at the hearing commencing from the 21 September 2020. Neither side was committed to extending the commercial relationship any further. Accordingly, the Judge below was not entitled to take into account, as he expressly did, the loss of the claimants' opportunity to recover fees thereafter. He held at para 111:

- The Judge below further observed:

- I do not follow this reasoning. Any relevant costs of the adjournment to be recovered from the defendant's husband would be limited to costs incurred by her to the claimants. The claimants' entitlement to and assessment of the level of costs against the defendant, whether by way of quantum meruit or otherwise, could not be dependent on what she subsequently sought to recover from Mr Atay.

- This leaves the assessment of 70% as being dependant almost entirely on the consequences of the claimants blocking out their respective diaries between 7 July 2020 and 31 August 2020 for a period of about four weeks from 7 September 2020. Evidence of the extent of this impact is set out in the claimants' witness statements.

- However, the Judge made no finding of the value of any actual benefit having been conferred upon the defendant as a consequence of the claimants' blocking out their diaries. He appears to have assumed that the evaluation of a claim brought by way of quantum meruit is based, at least primarily, upon detriment to the party bringing such a claim than of benefit to the recipient.

- I have every sympathy for the Judge on the quantum meruit issue as a whole. He was provided with little to work on but was nevertheless encouraged by the parties to make an adjudication. His understandable lack of enthusiasm for the task is reflected in his rueful observation in paragraph 108 of his judgment: "I shall have to proceed as best I can on what I have available to me."

- In these circumstances, I am reluctant to reach more than a tentative and provisional conclusion and further appreciate that my observations are, in any event, obiter. However, with these reservations in mind, I conclude that the Judge's approach was probably wrong. The general rule in, for example, cases in which no contract has been concluded but one party, in legitimate expectation of a binding agreement, expends money to the benefit of the other is that the level of restitution is generally assessed not by reference to the cost to the provider but the benefit of the recipient. Normally, where no benefit is conferred then no award is made.

- There remains much doubt as to the circumstances, if any, in which a quantum meruit claim must be founded upon an element of unjust enrichment (see, for example, Goff & Jones 16-18 – 16-19 in the context of work done in anticipation of a future agreement).

- For the reasons I have given, this judgment is not the place for any detailed exposition or resolution of this issue. Suffice it to say that I am not persuaded that the Judge was entitled to adopt the course he took in evaluating the element of quantum meruit and his conclusion was flawed.

- In summary my findings are as follows:

- It follows that this appeal is allowed. The claim for fees that was subject of this appeal be dismissed.

The Hon Mr Justice Turner :

INTRODUCTION

(i) the extent, if any, to which the provisions of the Consumer Rights Act 2015 ("the 2015 Act") operate so as to preclude the claimants from relying upon one of the central terms of their agreement relating to payment; and

(ii) the consequences which are to follow in the event that the 2015 Act so operates.

THE BACKGROUND

"I thought it would be helpful to set out the work that I will carry out for you and the fees that I will charge for this work.

The work I will carry out

The work you are instructing me to carry out is:

Preparation of and representation at the PTR hearing on the 10 July 2020, and the 10 [day] Final hearing commencing from the 21 September 2020, listed at the Central Family Court.

For the avoidance of doubt, the fee covers the above mentioned work and therefore if the hearing concludes early or is adjourned to another date or does not go ahead for any reason beyond our control, then the full fee is still payable and another fee will be payable for any adjourned hearing.

If subsequent work is needed on this matter, there will be another letter of agreement between us.

Because I carry out all my work personally and cannot predict what other professional responsibilities I may have in the future, I cannot at this stage confirm that I will be able to accept instructions for all subsequent work that may be required by your case.

My fees for this work

My fee for accepting the instruction to appear as an advocate on the occasions described above will be £90,000 plus VAT. You and I agree that I will not attend the hearing unless you have paid the fee in advance.

Total fees for my work as described above (exc. VAT): £90,000

VAT: £18,000

Total amount due: £108,000

The first payment of £12,550 is due by 6 July 2020

The second payment of £12,550 is due by the 10 July 2020

The third payment of £79,200 is due by the 31 August 2020

The final payment of £3,700 and any other fees due in respect of additional work is due 28 days after receiving the final order

Unless otherwise agreed failure to send payments on the aforementioned dates will mean that I will not be able to represent you at the hearings.

Any additional work will be billed at my hourly rate of £500 plus VAT."

[Emphasis not added]

THE BAR STANDARDS BOARD TEMPLATE

"13. The First Claimant's clerks sent the Defendant a contract (i.e., the First Contract) which follows the Bar Standards Board's:

"Model Client Care Letter (NoIntermediary)" (https://www.barstandardsboard.org.uk/resources/resource-library/public-access-model-client-care-letter-no-intermediary doc.html).

As permitted by the BSB Handbook, and following the model wording proposed by the BSB, the First Claimant and the Defendant agreed a fixed fee for the work the Defendant wished the First Claimant to undertake at the time it required to be undertaken. The practice of "rolling up" the refreshers into a fixed fee arises from the fact that, pursuant to the BSB Handbook, barristers are not permitted to hold client money. When they work for solicitors, of course the solicitor can hold the money required on account and release it as and when necessary; but that option is not open to barristers working on direct access. In order to have certainty regarding payment therefore, a fixed fee is sought which covers the work required to prepare the brief as well as the refreshers."

"Option 2: My fee for accepting the instruction to appear as an advocate on the occasion described above will be £XX plus VAT. You and I agree that I will not attend the hearing unless you have paid the fee in advance. If for any reason the case takes longer than one day, I will charge an extra fee of £XX per day plus VAT."

I observe:

(i) It as assumed that the services in question are likely to be limited to an attendance of one day only;

(ii) Refreshers are only to be paid in the event of the case lasting longer than one day and not in advance. N.B. The payment of refreshers does not have to be rolled up into a lump sum payable in advance in order to comply with the rule that a barrister is not permitted to hold client monies (see further the Bar Standards Board Guidance gC107 on this topic set out below).

(iii) The consequence of non-payment of the fee is that the advocate will be released from the obligation of attending the hearing; there is no express provision for payment or retention of fees in the event that the hearing does not go ahead.

THE DISPUTE ARISES

"For the avoidance of doubt, the fee covers the above mentioned work and therefore if the hearing concludes early or is adjourned to another date or does not go ahead for any reason beyond our control, then the full fee is still payable and another fee will be payable for any adjourned hearing."

This has been referred to both below and on appeal as "the payment term".

THE COMMON LAW

"There is an important distinction between a claim for payment of a debt and a claim for damages for breach of contract. A debt is a definite sum of money fixed by the agreement of the parties as payable by one party in return for the performance of a specified obligation by the other party or on the occurrence of some specified event or condition; whereas, damages may be claimed from a party who has broken his primary contractual obligation in some way other than by failure to pay such a debt. (It is also possible that, in addition to a claim for a debt, there may be a claim for damages in respect of consequential loss caused by the failure to pay the debt at the due date.) The relevance of this distinction is that rules on damages do not apply to a claim for a debt, e.g. the claimant who claims payment of a debt need not prove anything more than its performance or the occurrence of the event or condition; there is no need for it to prove any actual loss suffered by it as a result of the defendant's failure to pay; the whole concept of the remoteness of damage is therefore irrelevant; the law on penalties does not apply to the agreed sum; and the claimant's duty to mitigate its loss does not generally apply."

"…where an agreement provides for the payment of a sum of money, and does not make the performance of the thing which is the consideration for the payment a condition precedent to or concurrent with the payment, an action may be maintained for the recovery of the sum of money without such performance".

25. Thus, by the operation of the common law, the claimants, at least prima facie, became entitled to claim the full amount of their fees on 31 August regardless of the amount of work, if any, they had then done. I have rejected the argument raised on behalf of the defendant that the term relating to the level of the fee and that relating to the timing of payment related must stand or fall together. It is perfectly possible to delete all reference to the latter and to leave the rest of the agreement perfectly coherent. Indeed, section 67 of the 2015 Act provides:

"67 Effect of an unfair term on the rest of a contract

Where a term of a consumer contract is not binding on the consumer as a result of this Part, the contract continues, so far as practicable, to have effect in every other respect."

THE CONSUMER RIGHTS ACT 2015

TRADERS AND CUSTOMERS

PLEADINGS

"Duty of court to consider fairness of term

(1) Subsection (2) applies to proceedings before a court which relate to a term of a consumer contract.

(2) The court must consider whether the term is fair even if none of the parties to the proceedings has raised that issue or indicated that it intends to raise it.

(3) But subsection (2) does not apply unless the court considers that it has before it sufficient legal and factual material to enable it to consider the fairness of the term."

I conclude that, despite the opacity of some of the arguments articulated on behalf of the defendant, there was before me sufficient material to enable me to consider the fairness of the term. I do not, therefore, consider that it is necessary to grapple with the adequacy of the pleadings in so far as they relate to the operation of the 2015 Act. There was little or no dispute over the primary facts. The central issues thus relate to how the law is to be applied to such facts.

UNFAIR CONTRACT TERMS

"Requirement for contract terms … to be fair

(1) An unfair term of a consumer contract is not binding on the consumer…

(3) This does not prevent the consumer from relying on the term…if the consumer chooses to do so.

(4) A term is unfair if, contrary to the requirement of good faith, it causes a significant imbalance in the parties' rights and obligations under the contract to the detriment of the consumer.

(5) Whether a term is fair is to be determined—

(a) taking into account the nature of the subject matter of the contract, and

(b) by reference to all the circumstances existing when the term was agreed and to all of the other terms of the contract or of any other contract on which it depends.

"Exclusion from assessment of fairness

(1) A term of a consumer contract may not be assessed for fairness under section 62 to the extent that—

(a) it specifies the main subject matter of the contract, or

(b) the assessment is of the appropriateness of the price payable under the contract by comparison with the goods, digital content or services supplied under it."

These exceptions are said to provide a "safe harbour" for traders facing claims that their terms are unfair.

"This section does not apply to a term of a contract listed in Part 1 of Schedule 2."

"It is not disputed that a term appearing in the list need not necessarily be considered unfair and, conversely, a term that does not appear in the list may none the less be regarded as unfair... In so far as it does not limit the discretion of the national authorities to determine the unfairness of a term, the list contained in the annex to the Directive does not seek to give consumers rights going beyond those that result from Articles 3 to 7 of the Directive... Inasmuch as the list contained in the annex to the Directive is of indicative and illustrative value, it constitutes a source of information both for the national authorities responsible for applying the implementing measures and for individuals affected by those measures."

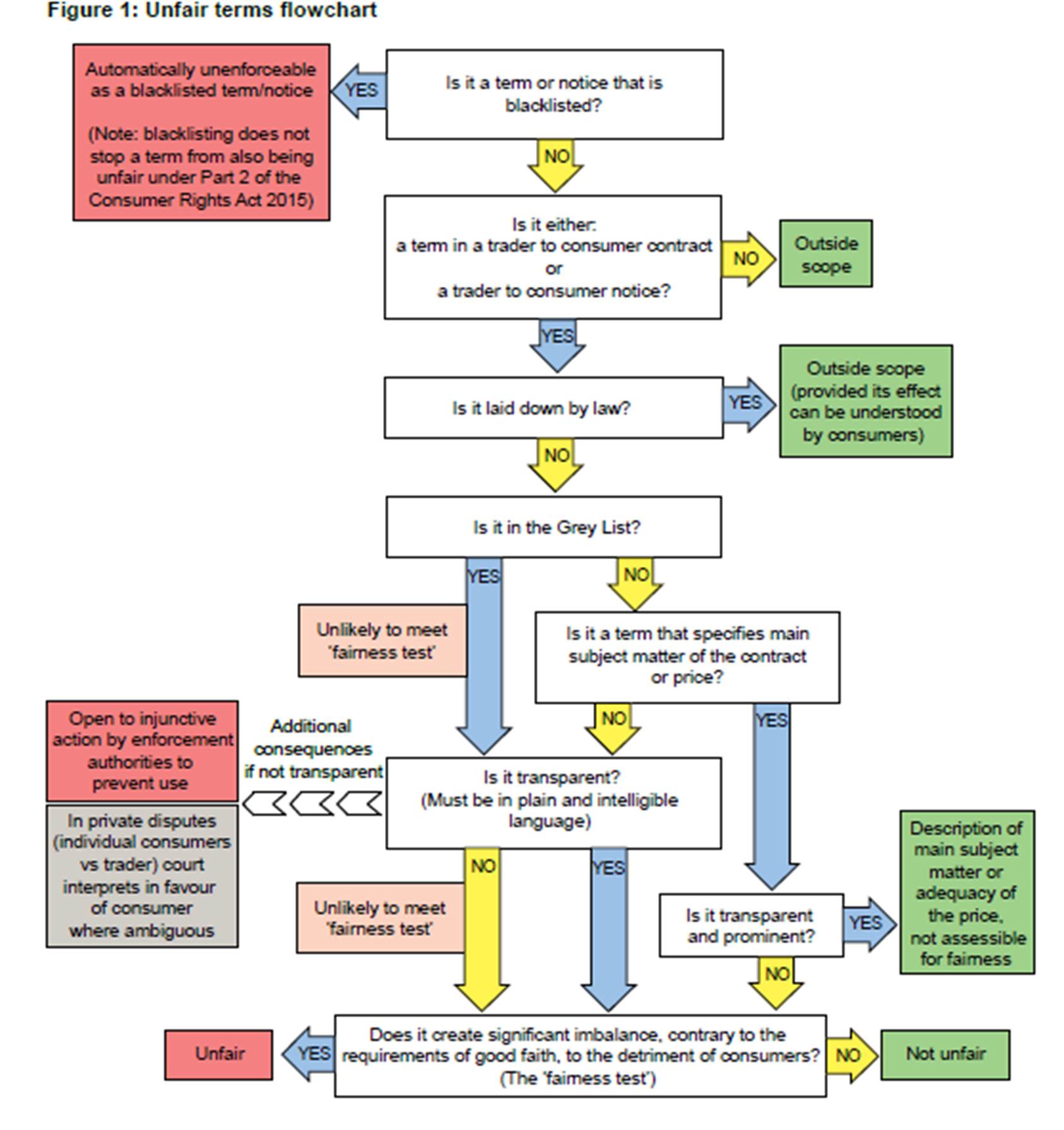

This approach was met with approval in the Guidance Notes to the 2015 Act. I have, in addition, appended to this judgment a flow chart which I have taken, with gratitude, from the Competition and Markets Authority "Guidance on the unfair terms provisions in the Consumer Rights Act 2015". Not all of the steps therein set out are material to the issues which arise on this appeal but the order in which those issues are to be determined and the consequences of such determinations at each stage provide a useful route to judgment. It is to his credit that the Judge below was able to work out the correct order of resolution of these issues (contrary to the submissions of the parties) without, it would appear, his attention having been specifically drawn to this route. (In paragraph 61 of his judgment he records the fact that the parties had proceeded on the erroneous basis that the "safe harbour" provisions should be considered before rather than after the "grey list".)

"5 A term which has the object or effect of requiring that, where the consumer decides not to conclude or perform the contract, the consumer must pay the trader a disproportionately high sum in compensation or for services which have not been supplied.

6 A term which has the object or effect of requiring a consumer who fails to fulfil his obligations under the contract to pay a disproportionately high sum in compensation."

"5.13.3 Where customers bring the contract to an end without any justification, and the trader suffers loss as a result, they cannot expect a full refund of all prepayments. But a term under which they always lose everything they have paid in advance, regardless of the amount of any costs and losses caused by the termination, is at risk of being considered an unfair financial sanction – see paragraph 6 of the Grey List, discussed in paragraphs 5.14.1 of the guidance onwards…

5.13.5…Generally, where the contract comes to an end because of the fault of the consumer, the business is entitled to hold back from any refund of prepayments what is likely to be reasonably needed to cover either its net costs or the net loss of profit resulting directly from the default…There is no entitlement to any sum that could reasonably be saved by, for example, finding another customer.

5.13.6 Alternatively, there may be no objection to a prepayment which is set low enough that it merely reflects the ordinary expenses necessarily entailed for the trader. A genuine 'deposit'– which is a reservation fee not an advance payment – may legitimately be kept in full, as payment for the reservation. But such a deposit will not normally be more than a small percentage of the price. A larger prepayment is necessarily more likely to give rise to fairness issues, for instance being seen as a disguised penalty…

Paragraph 5 of the Grey List covers the related issue of requiring consumers to pay for services which are supplied. The CMA considers that there is a potential for unfairness where terms can have the effect of

committing consumers to pay for services for an unduly lengthy tie-in period following the consumer's cancellation (see paragraphs 5.15.4–5.15.7 below)…

Disproportionate financial sanctions

5.15.1 Terms are always at risk of being considered unfair if they have the effect of imposing disproportionate sanctions on the consumer who decides to end the contract early. Paragraph 5 illustrates two different kinds of terms which are calculated to have this effect – disproportionate termination fees, and requirements which can operate so as to force consumers to pay for services they have not received..."

5.15.4 Requiring consumers to pay for services not supplied.

The CMA considers that the final words of paragraph 5 are relevant to terms that effectively lock consumers into paying for services. Terms can operate to create a fixed or 'tie-in' minimum contract period if they:

5.15.5 A service contract does not necessarily have to provide a formal right of cancellation without liability to be fair. In the CMA's view, however, it will be under suspicion of unfairness if the consumer who chooses to stop receiving the service is always required to pay in full or nearly in full, regardless of whether allowance could be made for savings or gains available as a result of the contracts' early termination…A saving may be available, for instance where there is scope to find other customers to take their place.

5.15.6 In some situations there may be less scope for the business to reduce its loss. In such cases, the focus of the fairness assessment will necessarily be on the length the period for which the consumer is tied in. In such cases, a minimum period for a service contract is, in the CMA's view, open to scrutiny, particularly if its effect is to give the trader an advantage arising from practical limitations to the consumer's ability to assess what their circumstances are likely to be in the longer term. In considering fairness, regard needs to be had to factors described above in part 2 of the guidance, under the 'Fairness test' heading."

"317 For example, if an individual contracts with a catering company to provide a buffet lunch, and the contract includes a term that the individual will pay £100 for a 3 course meal, the court cannot look at whether it is fair to pay £100 for 3 courses. It may, however, look at other things, such as the rights of the company and the individual to cancel the lunch, and when the price is due to be paid."

"5 A term which has the … effect of requiring that, where the consumer decides not to conclude or perform the contract, the consumer must pay the trader a disproportionately high sum…for services which have not been supplied."

WHAT IF THE TERM DOES NOT FALL WITHIN THE GREY LIST?

"Exclusion from assessment of fairness

(1) A term of a consumer contract may not be assessed for fairness under section 62 to the extent that—

(a) it specifies the main subject matter of the contract, or

(b) the assessment is of the appropriateness of the price payable under the contract by comparison with the goods, digital content or services supplied under it."

"The exclusion is narrow and must be strictly interpreted, restricted only to the 'essential obligations' of contracts. These could otherwise be referred to as the 'substance of the bargain', 'of central and indispensable importance' to the contract, as distinct from the ancillary 'incidental (if important) terms which surround them'. They represent what, objectively, both parties would view as the core bargain, and what in fact is the substance of the bargain. The exclusion does not apply to terms which set out secondary obligations, which apply only on breach of a primary obligation. It is important to look at the substance and reality of the transaction, not at the form. Although the language of the contract is important in this regard, it is not conclusive. The court must also look at the surrounding circumstances or contractual matrix, such as the market generally, the actual negotiation between the parties, and their assumptions, together with the actual package the consumer received, and what he pays for this."

"The object of the regulations is not price control nor are the regulations intended to interfere with the parties' freedom of contract as to the essential features of their bargain. But, that said, regulation 6(2) must be given a restrictive interpretation; otherwise a coach and horses could be driven through the regulations. So, while it is not for the court to re-write the parties' bargain as to the fairness or adequacy of the price itself, regulation 6(2) may be unlikely to shield terms as to price escalation or default provisions from scrutiny under the fairness requirement contained in regulation 5(1)."

It is to be noted that his observations reflected, in turn, the approach of Lord Bingham in Director General of Fair Trading v First National Bank Plc [2002] 1 A.C. 48.

IS THE TERM FAIR?

"gC107

If you have decided in principle to take a particular case you may request an 'upfront' fixed fee from your prospective client before finally agreeing to work on their behalf. This should only be done having regard to the following principles:

– it is a reasonable payment for the work being done; and

– in the case of public access work, that it is suitable for you to undertake.

"A term is unfair if, contrary to the requirement of good faith, it causes a significant imbalance in the parties' rights and obligations under the contract to the detriment of the consumer."

"A term falling within the scope of the Regulations is unfair if it causes a significant imbalance in the parties' rights and obligations under the contract to the detriment of the consumer in a manner or to an extent which is contrary to the requirement of good faith. The requirement of significant imbalance is met if a term is so weighted in favour of the supplier as to tilt the parties' rights and obligations under the contract significantly in his favour. This may be by the granting to the supplier of a beneficial option or discretion or power, or by the imposing on the consumer of a disadvantageous burden or risk or duty. The illustrative terms set out in Schedule 3 to the Regulations provide very good examples of terms which may be regarded as unfair; whether a given term is or is not to be so regarded depends on whether it causes a significant imbalance in the parties' rights and obligations under the contract. This involves looking at the contract as a whole. But the imbalance must be to the detriment of the consumer; a significant imbalance to the detriment of the supplier, assumed to be the stronger party, is not a mischief which the Regulations seek to address. The requirement of good faith in this context is one of fair and open dealing. Openness requires that the terms should be expressed fully, clearly and legibly, containing no concealed pitfalls or traps. Appropriate prominence should be given to terms which might operate disadvantageously to the customer. Fair dealing requires that a supplier should not, whether deliberately or unconsciously, take advantage of the consumer's necessity, indigence, lack of experience, unfamiliarity with the subject matter of the contract, weak bargaining position or any other factor listed in or analogous to those listed in Schedule 2 to the Regulations. Good faith in this context is not an artificial or technical concept; nor, since Lord Mansfield was its champion, is it a concept wholly unfamiliar to British lawyers. It looks to good standards of commercial morality and practice. Regulation 4(1) lays down a composite test, covering both the making and the substance of the contract, and must be applied bearing clearly in mind the objective which the Regulations are designed to promote."

"Whether a term is fair is to be determined—

(a) taking into account the nature of the subject matter of the contract, and

(b) by reference to all the circumstances existing when the term was agreed and to all of the other terms of the contract or of any other contract on which it depends."

CONSEQUENCES

"It is arguable that both the issues of principle and their application to the facts should have been more fully explored than they were…"

"32-077 In a contract for work to be done, if no scale of remuneration is fixed, the law imposes an obligation to pay a reasonable sum (quantum meruit). The circumstances must clearly show that the work is not to be done gratuitously before the court will, in the absence of an express contract, infer that there was a valid contract with an implied term that a reasonable remuneration would be paid. The court may infer from the facts a contract to pay for services to be rendered, even though this entails disregarding the actual intention of the parties at the time; as, for instance, where both parties, under a mistake of fact, assumed that the defendant was entitled to claim, without charge, the services of the particular fire brigade he had summoned."

"Where a party has performed only part of an entire obligation it can normally recover nothing, neither the agreed price, since it is not due under the terms of the contract, nor any smaller sum for the value of its partial performance, since the court has no power to apportion the consideration. The refusal of pro rata payment is based on the inability of the court, as a matter of construction, to add such a provision to the contract, and also upon the rule that the mere acceptance of acts of part performance under an express contract cannot, taken alone, justify the imposition of a restitutionary obligation to pay on a quantum meruit basis. Thus where an employee is engaged for a fixed period for a lump sum, but fails to complete the term for a reason other than breach of contract by the employer, e.g. frustration, the common law rule is that he can recover nothing. In the famous case of Cutter v Powell, to which reference has already been made, a seaman was to be paid a lump sum when he completed the voyage; he died before completion of the voyage and it was held that his executor could not recover pro tanto wages because it was an "entire contract"."

"57 Secondly, it should be recalled that Article 6(1) of Directive 93/13 provides that unfair terms are not binding on the consumer and must, therefore, be deemed never to have existed."

"64 The Court has held that if it were open to the national court to revise the content of unfair terms included in such a contract, such a power would be liable to compromise attainment of the long-term objective of Article 7 of Directive 93/13. That power would contribute to eliminating the dissuasive effect on sellers or suppliers of the straightforward non-application with regard to the consumer of those terms, in so far as those sellers or suppliers would still be tempted to use those terms in the knowledge that, even if they were declared invalid, the contract could nevertheless be modified, to the extent necessary, by the national court in such a way as to safeguard the interest of those sellers or suppliers…"

"I conclude that the termination of the retainer when there was no good reason…does amount to a breach of contract by Mrs Atay. She unilaterally decided to remove the prospect of the claimants acting further for her."

In the absence of any contractual obligation to instruct the claimants to do any such further work, she cannot be held to have been in breach.

"It is also relevant that they also lost the opportunity of securing a substantial payment for Mrs Atay from Mr Atay in respect of the adjourned trial, which would have taken a large part of the sting out of this dispute had they been successful."

CONCLUSION

(i) The payment term was one which fell within the parameters of paragraph 5 of the so-called "grey list" to be found in Part 1 Schedule 2 of the 2015 Act;

(ii) Even if it had not fallen within the grey list, it did not, in any event, fall within either of the categories excluded from assessment under section 64 of the 2015 Act;

(iii) The payment term was unfair under the provisions of section 62 of the 2015 Act;

(iv) The effect of this finding was that the contract fell to be treated as if the entirety of the payment term had never existed;

(v) The consequence of this was that there was an entire obligation upon the claimants which included attendance at the trial which, once the trial had been adjourned, was incapable of being fulfilled;

(vi) It followed that the claimants had no contractual right to payment of the agreed price at any time;

(vii) There was no legal basis upon which a non-contractual assessment by way of quantum meruit was appropriate;

(viii) Even if a claim by way of quantum meruit were theoretically available, the Judge below took into account impermissible factors in his approach to assessment and so his evaluation of 70% could not stand;

(ix) The Judge was probably wrong, in any event, to evaluate the assessment in the proportion of 70% based on the cost to the claimants rather than to any benefit to the defendant.