Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

Intellectual Property Enterprise Court

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> Intellectual Property Enterprise Court >> Madine (t/a Nico) & Anor v Phillips (t/a Leanne Alexandra) & ors [2017] EWHC 3268 (IPEC) (13 December 2017)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/IPEC/2017/3268.html

Cite as: [2017] EWHC 3268 (IPEC)

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

BUSINESS AND PROPERTY COURTS OF ENGLAND AND WALES

INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY LIST (CHD)

INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY ENTERPRISE COURT

7 Rolls Buildings London EC4A 1NL |

||

B e f o r e :

____________________

| (1) THELMA MADINE (T/A NICO) (2) CAMAL ENTERPRISES LIMITED T/A THE ENGLISH LADIES CO |

Claimants |

|

| - and – |

||

| (1) LEANNE PHILLIPS (T/A LEANNE ALEXANDRA) (2) PAULINE PHILLIPS & others (stayed) |

Defendants |

____________________

Ms Ashton Chantrielle (instructed by ead Solicitors LLP) for the Defendants

Hearing dates: 31 October and 1 November 2017

____________________

Crown Copyright ©

- This is a claim for infringement of the unregistered UK design right in two designs for wedding dresses. The main issue before me was whether the First Claimant's design rights were infringed by the Defendants by making a wedding dress, and by dealing in china figurines of a girl wearing such a dress.

- The First Claimant, Thelma Madine, makes and designs wedding dresses. For some years she has traded under the name "Nico" from a series of premises in the same road, Kempston Street, in Liverpool. Since about 1996 she has built up a specialist business designing and making dresses primarily for the traveller community, for weddings, communions and similar occasions. It seems that the hallmark of her dress designs is their extravagance, not just in terms of the price of the gowns, but in terms of the size and weight of the skirts, which tend to have to be supported by hoops (like a crinoline), and the elaborate nature of the decoration applied to the dresses.

- Ms Madine and her designs have become well-known as a result of her appearance on the Channel 4 television programmes "My Big Fat Gypsy Wedding." Two series of the show were broadcast in 2011 and 2012 as well as a number of individual programmes. Ms Madine has also appeared on a number of other television programmes, speaking about her dress designs, and has featured in the columns of national newspapers. She is the 'author' of two ghost-written books about her business and dresses. 'Tales of the Gypsy Dressmaker' was published by HarperCollins in 2012 and 'Gypsy Wedding Dreams' in 2013. I do not know how many of the books have been sold.

- The Second Claimant, which is a designer and importer of china figurines licensed by the Claimant, took no separate part in the trial.

- The Second Defendant, Pauline Phillips, is an old friend of Ms Madine, and worked with her from the early days of the business and as her employee from about 2008 until November 2013. She was employed primarily as the manageress of the shop but also carried out a variety of other tasks, as well as some design work when necessary. In particular, Pauline Phillips would meet customers on their first visit to the shop, discuss wedding dress designs with them in broad terms, and sketch out a rough design for them which would enable a price to be agreed.

- The First Defendant is Pauline Phillips' daughter, Leanne Phillips. She too worked for Ms Madine for a lengthy period from about September 2006 to December 2012. In about 2009 she became the head designer of Ms Madine's business. One of her roles was to refine the rough designs made by her mother.

- Both Pauline and Leanne Phillips appeared in episodes of the TV series.

- In December 2012, Ms Madine and Leanne Phillips fell out. The details of their dispute are irrelevant to this claim. Ms Madine dismissed Leanne, who successfully brought proceedings against Ms Madine for unfair dismissal.

- In early 2013, Leanne Phillips began trading under the name "Leanne Alexandra" running a competing wedding dress business. In about August 2013 her Facebook page became active, and she took over and traded from premises in Kempston Street previously occupied by Nico.

- Whilst Leanne's unfair dismissal proceedings were pending Pauline Phillips continued to work for Ms Madine. However, following the decision of the Employment Tribunal in Leanne's favour on 20 November 2013, she left. She brought proceedings against Ms Madine for constructive dismissal. Those proceedings failed. Pauline Phillips went to work for her daughter's business, who described her in her witness statement as acting as her general assistant.

- This dispute centres on the design of two wedding dresses. The first such design ("the Fan Dress") was made in 2011 for a bride called Delilah. Ms Madine said that Delilah first came to see her in about January 2010. Unusually for one of Ms Madine's customers, she wanted a very plain silk dress, without diamanté or crystals, but with 'piano pleats.' Ms Madine says that she came up with the idea of creating an unusual look for the dress by using pleated fabric arranged in a series of fan shapes over the skirt of the dress, and she and Leanne Phillips developed the design together ("the Fan Dress"). Leanne Phillips claims that the design was hers. The wedding was postponed before the dress was made. Ms Madine explained that it is not uncommon for traveller weddings to be postponed.

- There was some dispute at the trial over the details of the design process. Ms Madine's evidence was that her usual practice was that a rough sketch would be made when a bride first visited the shop, and later – closer to the time when the dress was to be manufactured - more detailed design drawings would be produced by her or by Leanne Phillips to give to her seamstresses for the dress to be made up. The Defendants accepted that there would be a two stage design process, but suggested that the bulk of the design work was done by Leanne Phillips.

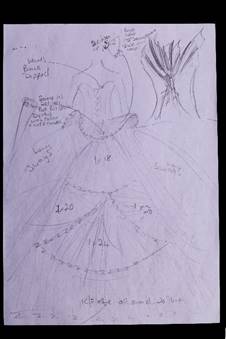

- Delilah returned to the shop in June 2011, the wedding having been rescheduled for August 2011. Ms Madine said that after meeting Delilah and discussing the design with Leanne Phillips she made a sketch of the dress which was approved by Delilah and then sent with the fabric to the factory which was going to machine the pleats. Ms Madine said that another sketch, a copy of which was produced in evidence, was produced to enable her staff to know how to make the dress. The Defendants denied that the latter sketch was contemporaneous, suggesting that it had been created for the purposes of these proceedings. The manufacture of the dress had to be hurried, and Ms Madine explained that they received fewer pleated panels than were necessary to provide pleats all over the skirt, so that they improvised the design of the back of the skirt, by including two layers of gathered swags, as well as pleats.

- Two photographs of Delilah wearing the dress featured in Ms Madine's first book. Those photographs show the dress from the rear and from the side, clearly showing the pleated fan details around the waist and bodice, though not the lower part of the back of the skirt (with the swags) nor the front of the skirt which was composed of a series of pleats. It was common ground that further photographs were posted on social media accounts, including Ms Madine's Facebook page, showing more views of the dress both in the shop and at the wedding (some examples are in Annex A). These show the numerous pleats in the skirt and how large it was. The Fan Dress also featured in the second book, where Ms Madine described it as "The Game-Changer."

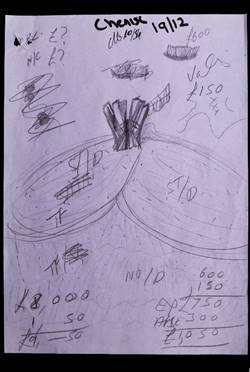

- On 29 February 2012, another bride, Chenise McCarthy, came to Ms Madine's premises, and met with Pauline Phillips. It is common ground that she said that she had seen a picture of the Fan Dress, and wanted to have a dress like it. Whilst she wanted the same pleated skirt, Chenise wanted diamanté decorations on both the bodice and skirt of her dress. It was agreed that the corset-style bodice would be decorated with strips of diamanté but it turned out not to be practical to put the diamanté on the pleated skirt. Mrs Phillips produced a rough sketch of the front of the dress for Chenise ("the early Chenise sketch"). The parties agreed that the sketch was supposed to represent the Fan Dress design with the amendments I have just mentioned ("the Chenise Dress"). Leanne Phillips also spoke to Chenise on that occasion, although the extent of her involvement was not made clear to me. The price was estimated and Chenise paid a deposit of £500. At that point Chenise's wedding was expected to be at the end of 2012. However, in about September 2012 Chenise (or her mother) informed Ms Madine that the wedding had been postponed.

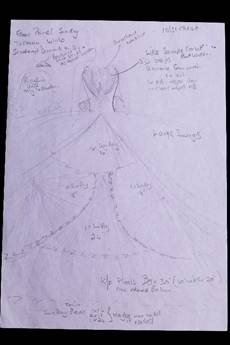

- Chenise returned to Nico in June 2013, wanting the same dress. Leanne Phillips had of course left by that date. Ms Madine's evidence was that she produced detailed design sketches of the front and back of the Chenise Dress at that stage ("the later Chenise sketches"). The Defendants deny that those drawing were made at that time. They claim that they were made at a later date and copied from the dress which Leanne Phillips later made for Chenise ("the Defendant's Dress) which the sketches resemble more closely than the earlier Chenise sketch.

- According to Ms Madine, Chenise telephoned again in the autumn of 2013 to say that her wedding had been postponed to 2014. Chenise did not go back to buy a wedding dress from Ms Madine but bought another dress with the deposit money.

- Instead, in January 2014 Chenise approached Leanne Phillips and asked her to make her wedding dress. It was not clear to me why Chenise went to Leanne Phillips for her dress. As I explain below, I do not accept Ms Phillips' explanation for this, and Pauline Phillips withdrew at trial a suggestion made in her witness statement that Chenise had stayed in touch with Leanne.

- After some discussion about the design, Leanne Phillips produced a dress which Chenise bought in November 2014. It is this dress ("the Defendant's Dress") which is alleged to infringe the First Claimant's design rights. Leanne Phillips denies copying either of the earlier designs. She claims that she always intended to and did make an original design for Chenise.

- In early 2015, Leanne Phillips entered into a written agreement with the Fourth Defendant, which procures the manufacture of china figurines, which I understand are collected by travellers. She agreed "to provide designs suitable for use in sculpting a range of figurines … in the form of photographs of her original dresses and design sketches to adapt or clarify design details to make them suitable for the manufacture of ceramic figurines." She was to be "consulted on the sculpting and colourway of each figurine" although the Fourth Defendant had "the final say." One of the designs provided to the Fourth Defendant by Miss Phillips was admitted to be the Defendant's Dress design. She said in her witness statement that she recalled sending photographs of the Defendant's Dress to the Fourth Defendant in about January 2015. In due course the Fourth Defendant produced figurines of a woman wearing a dress based upon that design (the "Crystal Figurine"). Leanne Phillips offered the Crystal Figurines for sale on her Facebook page. The Defendants' counsel accepted that there was no difference of substance between the Defendant's Dress and the dress of the Crystal Figurines, although the dresses are not of identical design (the skirt of the Figurine has an extra row of fans and the positioning of the fans at the waist of the dress is not the same).

- On learning of the production of the Crystal Figurines, Ms Madine took legal advice, and her solicitors sent a letter of claim to Leanne Phillips on 29 June 2015 complaining that the Defendant's Dress and the Crystal Figurines infringed her rights.

- The claim form was issued on 11 August 2015, alleging infringement of design rights and copyright, as well as passing off. The subsistence of design right in both designs was denied, as was infringement. In addition, Leanne Phillips made a counterclaim to design right but only in relation to the pattern of the crystals arranged on the front of the bodice of the Defendant's Dress.

- Various amendments were made to the claim both before and after HHJ Hacon gave directions on 21 December 2016. Certain claims in the action were stayed, including claims for design right infringement and passing off made against the 4th to 8th Defendants. In effect, the resolution of those claims is to follow the findings made upon this trial of liability against the First and Second Defendants. All questions of quantum were also reserved to a separate trial.

- As is usual in this Court, a List of Issues was appended to the Order dated 21 December 2016, some of which were helpfully resolved in the course of the trial.

- I heard evidence from Ms Madine and from both Pauline and Leanne Phillips. Dishonesty was alleged on both sides in a number of respects.

- Most of the significant facts which I have to decide occurred a number of years ago and it seems to me that all of the witnesses' memories may have been less than perfect, however certain they may have been in their own minds of the accuracy of their recollections. I think it right to bear in mind the helpful comments of Leggatt J (as he then was) about the unreliability of human memory in Gestmin SGPS S.A. v Credit Suisse (UK) Ltd [2013] EWHC 3560 (Comm) at [15]-[22] and then in Blue v Ashley [2017] EWHC 1928 (Comm) at [68]-[69]. In Gestmin he said, in particular:

- Ms Madine was alleged to have lied about the sketches of the Fan Dress which she had disclosed by claiming that they were contemporaneous - the Defendants said the sketches had been produced by Leanne Phillips some time later for her book. The Defendants also alleged that Ms Madine had fabricated the later Chenise sketches only after seeing the Defendant's Dress and for the purposes of making this infringement claim.

- I think it possible that in some respects Ms Madine's memory of events was not perfect, but I do not consider that she was seeking to mislead the Court, and I accept her explanation of the design process of both the Fan Dress and the later Chenise sketches. Ms Madine gave a logical explanation of the need for the later Chenise sketches; it seems to me that the earlier Chenise sketch would not have been adequate for the design to be made up in Ms Madine's factory. When Chenise returned to Ms Madine's shop in June 2013, Leanne Phillips was no longer employed there, and Ms Madine would have been the logical person to produce more detailed sketches of her dress design. Moreover, the later Chenise sketches have fewer pleated fans than either the Defendant's Dress or the Crystal Figurine, suggesting that the sketches were not copied from them. For all these reasons, I consider it far more likely than not that the sketches were genuine and were made in June 2013 or shortly afterwards.

- I found Ms Madine to be quite a balanced witness, given the unfortunate history of this matter. She was prepared to give credit to both of the Defendants for the help that they had given her in her business in the past; in particular, she was ready to give credit to Leanne Phillips as a very talented designer. Whilst her recollection of some of the events in question may not have been perfect, on the whole I consider that she was a reliable witness and I am satisfied, in the light of the agreed facts and the surrounding documents, that I should accept the central elements of her evidence.

- Pauline Phillips was alleged to have taken copies of the Chenise dress designs from the First Claimant's premises with a view to enabling her daughter to make the dress for Chenise. This was part of the basis of the claim made against her on the basis of joint tortfeasorship. It was also suggested to her that she was not a truthful witness, because she withdrew a damaging comment in her witness statement at trial, and because she claimed that she would not have been able to make copies of the Chenise sketches before she left Ms Madine's employment, saying she was unable to operate a photocopier. I did have concerns about the reliability of Pauline Phillips's evidence. In particular I found the suggestion that she would not have been able to make a photocopy (because, she said, she is dyslexic) quite extraordinary, especially as she had been working in Ms Madine's business for many years and was the manager of the business. She also gave two different explanations as to why she only drew the front of the dress for Chenise in February 2012, saying on the one hand that it was just to be a mirror image of the front and on the other that it was supposed to look like the back of the Fan Dress as shown in the photograph in the book. In the witness box, she denied that she was or had been working for her daughter, although the latter had said in her witness statement she was doing so. I concluded that she wanted to downplay the level of her involvement in the production of the Defendant's Dress. I have come to the conclusion that I should treat Pauline Phillips' evidence with a good deal of circumspection.

- The suggestion that her mother did not know how to make a photocopy was first made by Leanne Phillips in her oral evidence and, as I have said, I find that claim incredible. More significantly, Leanne Phillips was criticised for having given misleading evidence about the design of the Fan Dress. Ms Phillips said in her witness statement that the Fan Dress had "a 12 foot trail of overlapping swags." She produced some sketches which were exhibited to her witness statement and which were described in the Defendants' skeleton argument: "Due to the poor quality of the design drawings and photographs in this case, in an attempt to assist the Court in making its assessment, Leanne Phillips has helpfully prepared drawings of the [Fan Dress] and the [Defendant's Dress]. The sketches showed significant differences between the Fan Dress and the Defendant's Dress designs. In particular, her sketch of the Fan Dress showed it with several swags leading down from the hips (where the Defendant's Dress has a single swag) and with a single pleat at the back above what were marked as "10-12" overlapping swags of fabric, providing the train she mentioned, in contrast to the back of the Defendant's Dress, which had overlapping pleats, no swags, and no train, but a large bell shaped skirt.

- Ms Phillips claimed in cross-examination to have retained a clear idea of exactly how the Fan Dress had looked. Counsel took her to a series of photographs of the Fan Dress, including those in Annex A which had been disclosed from Ms Madine's Facebook page and some emails, asking about the design of the back of the dress. These did not show any such train but she maintained at length her stance that this was simply not shown in the photographs. Eventually, she accepted that the photographs proved that her sketch was inaccurate. There are several possible explanations for this. She may have intended to deceive the Court, in the belief that there were insufficient documents to contradict her, or may have been confused by a similar sketch in Ms Madine's book, or may simply have claimed a far better recollection of the dress designs than she had. Whatever the explanation, she was not a reliable witness on this important aspect of the case.

- Certain other aspects of Leanne Phillips' evidence also caused me some concern. For instance, she claimed in her witness statement that Chenise approached her in January 2014 because she was the one who had suggested the use of pleats for the dress when first Chenise came to Nico, although the Defendants admitted that Chenise went to Nico asking for a version of the Fan Dress. I also found it odd that Ms Phillips claimed not to have kept any sketches of the Defendant's Dress or the photographs which she had sent to the Fourth Defendant in January 2015.

- For all these reasons, again, I have come to the conclusion that I should also treat Leanne Phillips' evidence with a good deal of circumspection.

- The Defendants wished to rely upon an email sent apparently by Chenise to Leanne Phillips in June 2015, challenging a number of aspects of Ms Madine's evidence. I do not think it appropriate to place any weight upon that email, not least because I do not know the basis upon which it was solicited.

- Until 1 October 2014, section 213 of the Copyright, Patents and Designs Act 1998 provided that:

- On 1 October 2014 s.213(2) was amended by the Intellectual Property Act 2014 to delete the words "any aspect of". The impact of the amendment was considered recently by Henry Carr J in Neptune (Europe) Ltd v Devol Kitchens Ltd [2017] EWHC 2172 (Pat); [2017] E.C.D.R. 25. Two points of some relevance to these proceedings seem to me to flow from his decision. First, Carr J referred to the judgment of HHJ Hacon in DKH Retail Ltd v H Young Operations Ltd [2014] EWHC 4034 (IPEC); [2016] E.C.D.R. 9; [2015] FSR 21 at [10]–[18], who had concluded that the effect of the amendment is

- Secondly, Carr J considered whether the amendment had retrospective effect. He held at [34]-[42] that the amendment did not extinguish accrued rights of action for past infringements which occurred prior to 1 October 2014, but does apply to claims in respect of acts of infringement committed subsequent to that date.

- In my judgment, the designs in issue here consist of the whole or a part of the designs, not 'disembodied features,' and are unaffected by the amendment even if (which is not clear) the Defendant's Dress was made after 1 October 2014.

- The first issues which I have to decide relate to the subsistence of design right in the Fan Dress design, the earlier and later Chenise sketches and the bodice of the Defendant's Dress.

- In order to be protected by design right, a design must be "original." This is not simply a question of whether it is commonplace, and originality is tested in the same way as for copyright infringement (see for example Farmer's Build Limited v Carier Bulk Materials Handling Ltd [1999) RPC 461 at 475). Proving originality is not very onerous, whether set by reference to the UK test of not being a slavish copy, or the EU copyright requirement for a work to comprise the expression of the author's own intellectual creation (see the comments of Arnold J in Whitby Specialist Vehicles Ltd v Yorkshire Specialist Vehicles Ltd [2014] EWHC 4242 (Pat), [2016] FSR 5 at [43] and HHJ Hacon's comments in Action Storage Systems Ltd v G-Force Europe.com Ltd [2016] EWHC 3151 (IPEC), [2017] FSR 18 at [19]-[22].) Like the learned judge in Action Storage, I do not think that the distinction would make any difference in this case. Design right may subsist in a design parts of which have been copied from an earlier design, as was the case in Farmer's Build. The question is whether sufficient skill, effort and aesthetic judgment has been expended on the new design to make it original compared to the old one.

- The first listed issue was whether design right subsisted in the Fan Dress design. This was the design embodied in the dress made for Delilah, rather than in any preceding design document and related to the shape and configuration of the skirt portion (but not the bodice) of the dress. The pleaded features of the design were: the shape/silhouette of the skirt, the shape and relative size of the individual fans, the number, positioning and arrangement of the fans of the skirt as seen from the front, the shape of the portion immediately above the hem, the swags over the hips and the shape of the peplum. The design was not alleged to include the design of the back of the skirt with its combination of pleats and swags.

- It was not suggested by the Defendants that the pleaded design amounted to an arbitrary selection of "disembodied features" and it seems to me a legitimate claim to design right in part of an article (i.e. the skirt of the dress). By the end of the trial, the Defendants had abandoned their denial of the originality of that design and conceded that design right did subsist in it. No issue was taken as to ownership, as the design was made by Ms Madine and/or by Leanne Phillips, her employee at the time.

- The next issue was whether unregistered UK design right subsisted in the designs recorded in the earlier Chenise sketch and/or the later Chenise sketches. These were treated as being one design ("the Chenise Dress") in the Claimants' pleadings although both sides addressed me separately on the subsistence of design right in the earlier and later sketches.

- The earlier Chenise sketch, it was common ground, was intended to combine a skirt of the same design as that of the Fan Dress with a bodice on which strips of diamanté would replace (and give the impression of) the pleated front of the bodice of the Fan Dress. In addition, Chenise wanted diamanté scattered over the skirt.

- The earlier Chenise sketch mainly shows the front of the dress. It is difficult to make out the details as the sketch is rather faint as well as being only roughly sketched. However, it clearly shows the same kind of ruched swags at the sides of the skirt as those of the Fan Dress. It was suggested on behalf of the Defendants that those swags were not as long as those of the Fan Dress, but I do not think it is really possible to tell this from the sketch. It is just possible to make out the overlapping fan shaped pleats at the front of the skirt. Those features seem to me probably to be – as everyone involved intended - the same as those of the skirt of the Fan Dress. Chenise's desire for diamanté on the skirt is roughly shown by some dots on the skirt and by the letters "ST/D" on the side swags.

- The main difference related to the front of the bodice, for the reasons explained above. To the right of the main drawing is a very rough sketch of the back of the corset bodice, showing its lacing above a wavy peplum. The Fan Dress had a similar bodice and peplum, although its peplum apparently had more 'waves' than that shown in the sketch. A further difference of detail is the omission of the additional pleated fans found at the side of the bodice of the Fan Dress.

- At trial, the Defendants continued to contest the subsistence of design right in this sketch, on the basis that the addition of the diamanté to the dress would not have sufficed to make it original. The changes over Delilah's dress design (essentially in the design of the bodice) were said to be insufficient for a new design right to arise. It seems to me that the question of whether sufficient skill or creativity was expended by Pauline Phillips in making the earlier Chenise sketch is finely balanced but I have come to the conclusion that the changes that she made to the design were of some significance because the overall look of the bodice was quite different to that of Delilah's dress. Pleated fan features at the sides and front were replaced with a group of upright strips of material. In the circumstances, I find that there was design right in the earlier Chenise sketch or at least in the bodice element of that design. The right belongs to Ms Madine, as Pauline Phillips made the design in her capacity as her employee.

- The later Chenise sketches are more detailed and show the details of the shape of the skirt, the shape, size, positioning and arrangement of the pleated fans of the skirt, front and back, the side swags, and the waved peplum. The front of the bodice is different from that in the earlier Chenise sketch. The strips of material or pleats do not go down to the waist, but start just below the bust, and some additional decoration is shown on the bodice beneath the strips. All of those details were relied upon in the Particulars of Claim, except for the arrangement of the fans of the skirt when seen from the back. The Defendants' case on these sketches is that they were not original, because they were copied from the Defendant's Dress, and not produced by Ms Madine in 2013 as she claimed. As I have said, I reject that assertion. The Defendants conceded that if the later Chenise sketches predated the Defendant's Dress, design right would subsist in the design and would belong to Ms Madine. I so find.

- A final element of the question of subsistence of design right was raised in relation to a claim by the Defendants that design right subsisted in the pattern of the crystals arranged on the front of the Defendant's Dress. This rather arid point was not seriously pursued at the trial and in any event I consider that I am not able to resolve this issue in the absence of any adequate representation of that pattern.

- Under section 226 of the 1998 Act, the owner of a design right has the exclusive right to reproduce the design for commercial purposes and sub-section 226(2) provides that "reproduction of a design by making articles to the design means copying the design so as to produce articles exactly or substantially to that design." So in order to establish primary infringement a claimant must show that its design was directly or indirectly copied by the defendant so as to produce the articles complained of, and such articles must be exactly or substantially to the claimant's design.

- UK unregistered design is not infringed by someone who makes an article which was created independently; there must have been copying, although that copying may have been direct or indirect. Indirect copying may arise where verbal instructions are given which afford a sufficient causal link to the earlier design (see Solar Thomson Engineering Co. Ltd. v Barton [1977] R.P.C. 537 at p 560). Generally, where there is substantial similarity this will be seen as prima facie evidence of copying, particularly when coupled with proof of access to the earlier design.

- The evidence before me contained remarkably few adequate representations of the Defendant's Dress. The Defendants had not produced any design drawings of the dress, apart from a couple of rough sketches included within Leanne Phillips' Facebook Messenger exchanges with Chenise, and the only photographs are of poor quality or do not show the whole of the dress. Ms Chantrielle suggested that the Crystal Figurine could be taken to show the details of the design of the Defendant's Dress, however, the figurine is not a reliable guide to the dress, as there are some discernible differences between them, for instance in the number and arrangement of fans in the skirt. I am however satisfied that the most significant features of the dress can be made out from the disclosed photographs, and in particular in the photographs at Annex C hereto, and I have carried out the comparison by reference to those photographs rather than the Crystal Figurine.

- In my view, the Defendant's Dress includes the most significant of the pleaded features of the Fan Dress design, namely the shape/silhouette of the skirt, the shape and relative size of the fans, the number, positioning and arrangement of the fans of the skirt from the front, and the swags over the hips. There is one difference, which is that the peplum of the Fan Dress has more 'waves' than the peplum of the Defendant's Dress. I do not consider that to be a significant difference. Ms Chantrielle submitted that the side swags were longer in the Defendant's Dress than in the Fan Dress design (relying mainly upon how they appear in the Crystal Figurine) but as this cannot be seen in the photographs I do not accept that I should make that finding. There is only one pleaded feature which may be missing altogether in the Defendant's Dress, and that is the shape of the bottom of the skirt immediately above the hem. It is not possible to know whether the Defendant's Dress included the same detail, as this part of the dress cannot be seen in the available photographs. Plainly, the back of the skirt of the Defendant's Dress lacks the central swags of the Fan Dress which I have mentioned above, but this was not a pleaded feature of the design. In my view there are substantial similarities between the Fan Dress design and the Defendant's Dress design, and these are quite substantial enough to raise an inference of copying.

- Both of the Defendants were very familiar with the Fan Dress design. Indeed, Leanne Phillips was its co-designer or had at least been intimately involved in its design and manufacture. Moreover, what Chenise wanted from 2012 onwards was a version of the Fan Dress; it is admitted that she came to Nico seeking such a dress, and Leanne Phillips also gave evidence that Chenise came to her in 2014 wanting "the Delilah dress." The explanations given by Leanne Phillips went to the manner in which the Defendant's Dress was made, not how it was designed, and I do not accept that they counter the strong inference that the design was copied.

- In the circumstances, I am satisfied that the similarities between the two designs arise from copying, which in the circumstances must have been deliberate, even if Leanne Phillips might have preferred (as she claimed) to produce a wholly original design.

- As for copying the designs embodied in the Chenise sketches, I am not persuaded that Pauline Phillips made copies of the later Chenise sketches which she took with her when she left her employment with Ms Madine. This allegation was based upon an assumption by Ms Madine and it seems to me that there was no reason why, in November 2013, Pauline Phillips would have expected those sketches to be of use to her daughter, as Chenise's wedding was apparently 'on hold' at that time.

- Nevertheless, in my view, the Defendant's Dress was deliberately copied from the earlier and/or later Chenise sketches as well as from the Fan Dress design, as there are further substantial similarities between it and those designs. It copies the bodice, decoration and peplum of the later Chenise sketches. Such copying could have been based upon Leanne Phillips' own knowledge of the details of the earlier Chenise sketch, but given the details of the design of the bodice I think it more probable that she relied upon a description of the variations to the Fan Dress design that were incorporated into the later Chenise sketches, whether described to her by Pauline Phillips or by Chenise herself. Mr St Quintin relied on the exchanges disclosed between Leanne Phillips and Chenise, and I accept that they indicate that Chenise had a clear idea of how the dress was 'supposed' to look. I think it a fair inference that it was supposed to look like the version of the Fan Dress that Chenise had discussed first with Pauline and Leanne Phillips in 2012 and with Ms Madine in June 2013. There are some differences in the design of the skirt, which I discuss below, and the bodice of the Defendant's Dress had additional crystals applied to the bodice which were not shown in the early Chenise sketch and not shown in any useful detail in the later Chenise sketches, but I am nevertheless satisfied that the Defendant's Dress was copied indirectly from the Chenise sketches.

- As noted above, Leanne Phillips admits providing the manufacturer with photographs of the Defendant's Dress and that the dress of the Crystal Figurine was copied from and is a 'figurine version' of the Defendant's Dress. It is in my view an indirect copy of the Claimant's designs.

- In Virgin Atlantic Airways Ltd v Premium Aircraft Interiors Group Ltd [2009] EWHC 26 (Pat); [2009] ECDR 11, Lewison J said:

- Despite the differences which I have discussed above between the Defendant's Dress and the Fan Dress design, in my judgment the Defendant's Dress is made substantially to that design. The great majority of the features of the design in which design right subsists have been replicated. The number, size and arrangement of the fans at the front are in my view identical, as are the swags over the hips and the general shape of the skirt, and these are particularly striking features of the Fan Dress design. This is not, as I think was suggested, a case in which no more than an idea has been copied, but I find that there was wholesale copying of the most original features of the Fan Dress design. In my judgment, the slightly different shape of the peplum is insignificant. I consider that someone to whom the design was directed – the customer - would have seen the two designs as substantially similar.

- In my judgment, the Defendant's Dress infringes the design right in the Fan Dress design.

- My initial impression was that the Defendant's Dress was more similar still to the later Chenise sketches. The Claimants submitted that its skirt had all the same similarities, the peplum was the same and the bodices were very similar, so that when assessed through the eyes of the person to whom they are directed, they would be considered to be exactly or substantially the same. On closer examination, though, it can be seen that there are fewer 'fans' making up the skirt of the dress in the later Chenise sketches than there are in either the Fan Dress design or the Defendant's Dress. In my judgment, however, that difference does not prevent the Defendant's Dress from being substantially similar to the later Chenise sketches. I am fortified in that view by the fact that the Defendants admitted that there was no difference of substance between the Defendant's Dress and the dress of the Crystal Figurines, although the skirt of the figurines is not identical to that of the Defendant's Dress, in part because it has an extra row of fans.

- In the circumstances, I also find that the design right in the later Chenise sketches is infringed by the Defendant's Dress.

- As I have said above, the Defendants accepted that if the Defendant's Dress infringed, so did the Crystal Figurine, despite the differences in the design of the skirt shown in the figurine.

- There was a further issue as to whether Pauline Phillips was jointly liable with her daughter for any infringements. First, she was alleged to be primarily liable for infringement by taking copies of the later Chenise sketches. As I have already said, I do not find that allegation to have been proved.

- Secondly, Pauline Phillips was alleged to be jointly and severally liable with her daughter for the infringements arising from making of the Defendant's Dress. Kitchin J (as he then was) in Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp v Newzbin Ltd [2010] EWHC 608 (Ch); [2010] FSR 21, said at [108]:

- Mr St Quintin put the claim on the basis of a common design to secure the making of the infringing articles, suggesting that what he had to show was that Pauline Phillips "actively co-operated to bring about the act of the primary tortfeasors" and intended that her cooperation would bring about the acts of infringement (see Vertical Leisure Ltd v Poleplus Ltd [2015] EWHC 841 at [66]).

- It was suggested that Pauline Phillips had encouraged Chenise to get her wedding dress from her daughter rather than from Ms Madine, but it does not seem to me that there was any evidence before me to prove that she did so. There was some evidence that Pauline Phillips had been working for her daughter at the relevant time, but what she was doing was unclear. She denied having been instrumental in the development of the Defendant's Dress. In my view, there was no evidence of a "common design" and the Claimants have not proved that she is jointly liable with her daughter for making the infringing dress.

- Under sub-sections 226(1) and (3) of the 1988 Act, design right is infringed by a person who authorises another to make articles to a design without the licence of the design right owner. Authorisation means the grant or purported grant of the right to do the act complained of, it does not include mere enablement, assistance or even encouragement of the infringement. See Twentieth Century Fox v Newzbin (above) at [90].

- Whilst Leanne Phillips accepted that if the Defendant's Dress infringed the First Claimant's designs, so did the Crystal Figurines, she denied liability for having authorised the infringement. I understood her defence to be that she had not authorised the reproduction of the First Claimant's designs in the figurines, but had merely enabled the Fourth Defendant to make them.

- I have set out the essential terms of the agreement between Leanne Phillips and the Fourth Defendant at paragraph 20 above. In my judgment, this is not a case in which there was mere enablement of infringement by third party. Not only did Leanne Phillips provide photographs of the Defendant's Dress to the Fourth Defendant specifically to make figurines which would embody copies of the dress, but under the contract she had the right to exercise some control (even if not the final control) over the design of the figurines. The Fourth Defendant undertook to consult her, take her opinions into account and "respect her designs and endeavour to produce them faithfully as much as the constraints of ceramic manufacture allow."

- In those circumstances, it seems to me that this was a case in which the manufacture of the infringing Crystal Figurines was authorised by Leanne Phillips.

- In addition to authorisation, the Particulars of Claim included an allegation of infringement by Leanne Phillips by the sale and offer for sale of the Crystal Figurines when she knew or had reason to believe that they were infringing copies of the First Claimant's designs. She of course admitted having offered the Figurines for sale, and in the light of my findings of fact and on infringement, Ms Phillips' liability for this secondary infringement must follow the liability for the primary infringement.

- For the reasons given above the claim for design right infringement succeeds as against Leanne Phillips but fails as against Pauline Phillips. I will hear counsel as to the appropriate form of order to make.

Miss Recorder Amanda Michaels:

The factual background

The witnesses

"[18] Memory is especially unreliable when it comes to recalling past beliefs. Our memories of past beliefs are revised to make them more consistent with our present beliefs. Studies have also shown that memory is particularly vulnerable to interference and alteration when a person is presented with new information or suggestions about an event in circumstances where his or her memory of it is already weak due to the passage of time.

[19] The process of civil litigation itself subjects the memories of witnesses to powerful biases. The nature of litigation is such that witnesses often have a stake in a particular version of events. This is obvious where the witness is a party or has a tie of loyalty (such as an employment relationship) to a party to the proceedings. ...

[20] Considerable interference with memory is also introduced in civil litigation by the procedure of preparing for trial. A witness is asked to make a statement, often (as in the present case) when a long time has already elapsed since the relevant events. The statement is usually drafted for the witness by a lawyer who is inevitably conscious of the significance for the issues in the case of what the witness does nor does not say. The statement is made after the witness's memory has been "refreshed" by reading documents. The documents considered often include statements of case and other argumentative material as well as documents which the witness did not see at the time or which came into existence after the events which he or she is being asked to recall. The statement may go through several iterations before it is finalised. Then, usually months later, the witness will be asked to re-read his or her statement and review documents again before giving evidence in court. The effect of this process is to establish in the mind of the witness the matters recorded in his or her own statement and other written material, whether they be true or false, and to cause the witness's memory events to be based increasingly on this material and later interpretations of it rather than on the original experience of the events.

…

[22] In the light of these considerations, the best approach for a judge to adopt in the trial of a commercial case is, in my view, to place little if any reliance at all on witnesses' recollections of what was said in meetings and conversations, and to base factual findings on inferences drawn from the documentary evidence and known or probable facts. This does not mean that oral testimony serves no useful purpose – though its utility is often disproportionate to its length. But its value lies largely, as I see it, in the opportunity which cross-examination affords to subject the documentary record to critical scrutiny and to gauge the personality, motivations and working practices of a witness, rather than in testimony of what the witness recalls of particular conversations and events. Above all, it is important to avoid the fallacy of supposing that, because a witness has confidence in his or her recollection and is honest, evidence based on that recollection provides any reliable guide to the truth."

Subsistence and ownership of design rights

"(1) Design right is a property right which subsists in accordance with this Part in an original design.

(2) In this Part 'design' means the design of any aspect of the shape or configuration (whether internal or external) of the whole or part of an article."

"that it no longer permits a claim to unregistered design right to extend to designs other than those specifically embodied in all or part of the claimant's article, i.e. no more UK unregistered design rights in abstract designs …"

Carr J held at [33], that the amendment made a substantive change to the law "by preventing claims in respect of disembodied features, arbitrarily selected, which are not, in design terms, parts of the design."

Infringement

"[31] … even if the design has been copied, the infringing article must be produced "exactly or substantially" to the copied design. Mere similarity is not enough."

[32] In C&H Engineering v F Klucznik & Sons Ltd (No.1) [1992] F.S.R. 421 Ch D Aldous J. said:

"Under section 226 there will only be infringement if the design is copied so as to produce articles exactly or substantially to the design. Thus the test for infringement requires the alleged infringing article or articles be compared with the document or article embodying the design. Thereafter the court must decide whether copying took place and, if so, whether the alleged infringing article is made exactly to the design or substantially to that design. Whether or not the alleged infringing article is made substantially to the plaintiff's design must be an objective test to be decided through the eyes of the person to whom the design is directed."

[33] Although, at least in theory, two separate criteria must be satisfied viz. copying and making articles exactly or substantially to the copied design, it is not easy to conceive of real facts (absent an incompetent copyist) in which a design is copied without the copy being made exactly or substantially to the copied design. In practice, if copying is established, it is highly likely that the infringing article will have been made exactly or substantially to the protected design. If copying is not established, then whether the article is the same or substantially the same as the protected design does not matter. However, similarity in design may allow an inference of copying to be drawn."

The Second Defendant's liability

"I derive from those passages that mere (even knowing) assistance or facilitation of the primary infringement is not enough. The joint tortfeasor must have so involved himself in the tort as to make it his own. This will be the case if he has induced, incited or persuaded the primary infringer to engage in the infringing act or if there is a common design or concerted action or agreement on a common action to secure the doing of the infringing act."

Liability for infringement in the form of the Crystal Figurine

Conclusion

| Front view |  |

| Back view |  |

| Delilah on her wedding day |   |

Annex B

| The earlier Chenise sketch |

|

|

|

| The later Chenise sketches | |

|

|

Annex C

Chenise wearing the Defendant's Dress:

Annex D

The Crystal Figurine: