Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

England and Wales High Court (Commercial Court) Decisions

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> England and Wales High Court (Commercial Court) Decisions >> Upham & Ors v HSBC UK Bank PLC (Rev1) [2024] EWHC 849 (Comm) (26 April 2024)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Comm/2024/849.html

Cite as: [2024] EWHC 849 (Comm)

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

Neutral Citation Number: [2024] EWHC 849 (Comm)

Case No: CL-2020-000347

IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE

BUSINESS AND PROPERTY COURTS OF ENGLAND AND WALES

COMMERCIAL COURT (KBD)

Royal Courts of Justice, Rolls Building

Fetter Lane, London, WC4A 1NL

Date: 26 April 2024

Before :

MR JUSTICE BRIGHT

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Between :

|

|

Christopher Bernard Upham and others |

Claimants |

|

|

- and - |

|

|

|

HSBC UK Bank plc |

Defendants |

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Philip Coppel KC and Zachary Kell (instructed by Edwin Coe LLP) for the Claimants

Andrew Green KC, Simon Pritchard and Dominic Howells (instructed by Norton Rose Fulbright LLP) for the Defendants

Hearing dates: 5, 6, 7, 8, 12, 13, 14, 15, 19, 20, 21, 22, 26, 27, 28, 29 February 2024, 4, 5, 18, 19, 20, 21, 25 March 2024

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Approved Judgment

This judgment was handed down remotely at 9:15am on 26/04/24 by circulation to the parties’ representatives by e-mail and by release to the National Archives.

.............................

II: The main entities and individuals. 8

II(iii): Professional advisers to Future Films/Eclipse. 10

III: The Eclipse structure. 10

III(i): The essence of the Eclipse scheme. 10

III(ii): Eclipse Tranches 1 to 5. 11

III(iii): The roles of Future Films and of the Members. 11

III(iv): The Eclipse Loans and the Lending Bank. 11

III(vi): The Licensing Agreement 12

III(vii): Further Disney agreements: the Distributor and the MSP. 13

III(viii): The media analysts. 13

IV: The effect of the Eclipse structure. 13

IV(ii): The effect in terms of money-flow.. 14

IV(iii): Profit at the level of each LLP. 15

IV(iv): Loan Interest Relief for each individual Member 15

IV(v): The cost to individual Members and the rationale. 16

V: The Information Memorandum and Addenda. 16

V(i): Marketing to IFAs and to individual investors. 16

V(ii): Parties named in the Information Memorandum.. 16

V(iii): The Information Memorandum and trade/trading. 17

V(iv): The Information Memorandum and legal advice. 18

V(v): The Information Memorandum and Contingent Receipts. 18

VI: Consultations with Mr Peacock QC.. 20

VI(ii): The consultation of 8 September 2005. 21

VI(iii): The consultation of 20 October 2005. 21

VI(iv): The consultation of 22 December 2005. 23

VI(v): Subsequent consultations. 26

VII: The Consolidated Peacock Note of 18 January 2006. 26

VII(i): Section 1 - Summary of the instructions to counsel 26

VII(ii): Section 2 - Specific questions. 27

VII(iii): Section 3 - Trade. 27

VII(iv): Paragraph 3.3 - Questioning the entire transaction. 27

VII(v): Paragraph 3.3 - Information about Contingent Receipts. 28

VII(vi): Paragraphs 3.6 to 3.10 - Conclusion on “trade”. 29

VII(vii): Paragraph 11.4 - Circular money-flow.. 30

IX: Other information from Future Films for investors/IFAs. 31

IX(i): The Eclipse Key Features document 31

IX(ii): The Eclipse PowerPoint Presentation. 31

IX(iii): The KPMG Accounting Review.. 31

IX(iv): Individual financial illustrations. 32

X: Mr Bowman’s role in marketing. 33

X(ii): Mr Bowman’s presentation to E&Y partners. 33

X(iii): Information to IFAs. 33

XI: Significant agreements. 34

XI(i): Negotiation of the agreements. 34

XI(ii): The Licensing Agreement 35

XI(iii): The Marketing Services Agreement 36

XI(v): The Distribution Agreement 38

XI(vi): The Future-HSBC Agreement 39

XII: Review of the Eclipse agreements by advising lawyers. 40

XII(i): The reference in the Addenda to a review by DLA.. 40

XII(ii): Was there a review by DLA?. 41

XIII: The implementation of the Eclipse scheme. 42

XIII(i): The movement of funds for each Eclipse LLP. 42

XIII(ii): The activities of the MSP. 43

XIII(iii): The activities of Future Films. 44

XIV: Restructuring and Ceasing Member arrangements. 46

XIV(i): Tax deferral and tax avoidance. 46

XIV(ii): Restructuring and Ceasing Member Arrangements. 47

XV: The timeline of the HMRC challenge to Eclipse 35. 47

XV(i): The HMRC decision re Eclipse 35. 47

XV(ii): The chronology of the HMRC Proceedings. 48

XV(iii): The relevance of this chronology. 48

XVI: The consequences of the HMRC Proceedings. 48

XVI(i): Effect on tax deferral for Eclipse 35. 49

XVI(ii): HMRC Follower Notices re other Eclipse LLPs. 49

XVI(iii): Late payment interest 49

XVI(v): Ceasing Member Arrangements. 50

XVII(i): The Newport action group. 50

XVII(ii): The ARC action group. 51

XVIII: Why Eclipse 35 lost in the HMRC Proceedings. 51

XVIII(ii): The conclusion that Eclipse 35 was not trading. 52

XVIII(iii) Whether the MSP was the LLP’s agent 53

XVIII(iv): Whether the MSP/LLP contributed to marketing/distribution. 53

XVIII(v): Whether the licence/sub-licence involved speculation. 54

XVIII(vi): Whether Contingent Receipts were too remote. 54

XIX: Divergence from the basis of Mr Peacock QC’s advice. 56

XIX(i): The MSP was not the LLP’s agent 56

XIX(ii): No involvement of the MSP/LLP in marketing/distribution. 57

XIX(iii): No documentary record of the MSP’s activities. 57

XX: Non-divergence from the basis of Mr Peacock QC’s advice. 58

XX(i): The prospect of Contingent Receipts. 58

XX(ii): The circular movement of funds. 59

XXI(i): Outline of the core complaint 59

XXI(ii): The representation in the Information Memorandum.. 60

XXI(v): The legal significance of this analysis. 61

XXI(vi): The relevant dates. 62

XXII: The Claimants’ case on the core complaint 62

XXII(i): The alleged Advice Representation. 62

XXII(iii): Knowledge/dishonesty. 63

XXII(iv): Joint tortfeasance/conspiracy. 64

XXII(v): Dishonest assistance. 64

XXIII: HSBC’s case on the core complaint 65

XXIV: The Claimants’ case as to other representations. 65

XXIV(i): The alleged Trade Representation. 65

XXIV(ii): The alleged Contribution Representation. 66

XXIV(iii): The alleged Profit Representation. 66

XXV: The Claimants' Sample Witnesses. 67

XXV(i): Limited recollection. 67

XXV(ii): Eclipse was a tax deferral scheme. 67

XXV(iii): Reliance on the support of a tax QC.. 68

XXV(iv): Investment in films and Contingent Receipts. 68

XXV(v): Circular money-flow.. 69

XXV(vi): Awareness of the HMRC challenge to Eclipse 35. 69

XXV(vii): Restructuring and Ceasing Member Arrangements. 69

XXV(viii): Concern about Dry Tax. 69

XXV(x): Knowledge/ignorance of the role of HSBC.. 70

XXV(xi): Evidence of losses. 71

XXV(xii): Tax deferral/aggressive tax avoidance. 71

XXVI: HSBC’s factual witnesses. 72

XXVI(iii): Other HSBC witnesses. 73

XXVII(i): Mr Sills and Mr Fier 73

XXVII(iii): Whether there was a real prospect of Contingent Receipts. 74

XXVIII: Representations regarding Mr Peacock QC’s advice. 76

XXVIII(i): The relevant representations. 76

XXVIII(ii): Representations by Future Films. 77

XXVIII(iii) Representations by HSBC.. 77

XXIX(i): Intention that potential investors should rely. 78

XXIX(ii): Reliance by the Claimants' Sample Witnesses. 78

XXX(i): The Claimants’ pleaded case as to falsity. 78

XXX(ii): Did Future Films/Mr Bowman have the expectation/opinion?. 79

XXX(iii): Did Future Films have reasonable grounds?. 79

XXX(iv): Did Mr Bowman have reasonable grounds?. 80

XXXI: Knowledge/dishonesty of Future Films. 81

XXXI(i): Knowledge, blind-eye knowledge, recklessness, dishonesty. 81

XXXI(ii): The Claimant’s case in relation to Future Films. 82

XXXI(iii): Future Films’ initial negotiations with Disney. 82

XXXI(iv): The contractual negotiations in February/March 2006. 83

XXXI(v): Mr Clarance’s emails in May 2006. 84

XXXII: HSBC’s knowledge/dishonesty. 85

XXXII(i): The Claimants’ case in relation to Mr Bowman/HSBC.. 85

XXXII(ii): Blind-eye knowledge. 85

XXXII(iii): Mr Bowman’s Waiver Letters. 86

XXXII(iv): The 7 Arts emails. 87

XXXII(v): Mr Bowman’s statements to others. 88

XXXIII: Conclusion on deceit 89

XXXIV: Direct representations by HSBC.. 90

XXXV: Joint tortfeasance and conspiracy. 91

XXXV(i): The Claimants’ case. 91

XXXV(ii): Analysis and conclusion. 91

XXXVI: Dishonest assistance. 92

XXXVII(i): Legal principles. 93

XXXVII(ii): Analysis and conclusion. 93

XXXVIII(i): FSMA and COB 2.1.3R.. 94

XXXVIII(ii): The applicability of COB 2.1. 95

XXXVIII(iii) Alleged breaches of COB 2.1.3R.. 96

XXXIX(ii): Personal Contributions, HMRC late payment interest 97

XXXIX(iii): Restructuring Arrangement fees. 97

XXXIX(iv): Ceasing Member Arrangement fees. 98

XXXIX(v): Fees to Future Films and to other advisers, etc. 99

XL(i): The losses suffered by the Claimants' Sample Witnesses. 99

XL(ii): Whether credit must be given for profits made. 99

XL(iii): There is no evidence as to the quantum of this credit 100

XLI(ii): The Claimants’ case. 104

XLI(iii): When did the Claimants know something had gone wrong?. 105

XLI(iv): When could fraud have been discovered?. 107

XLI(v): Conclusion on section 32(1)(a) 109

XLI(vi): Limitation and the FSMA claims. 109

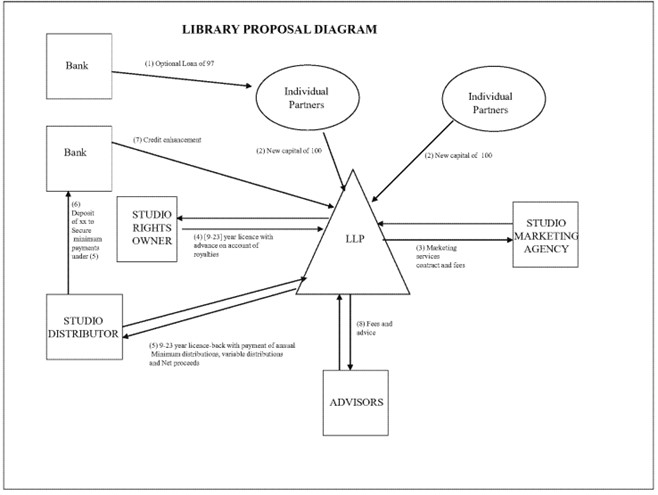

Appendix 1: Structure Diagram provided to Mr Peacock QC.. 112

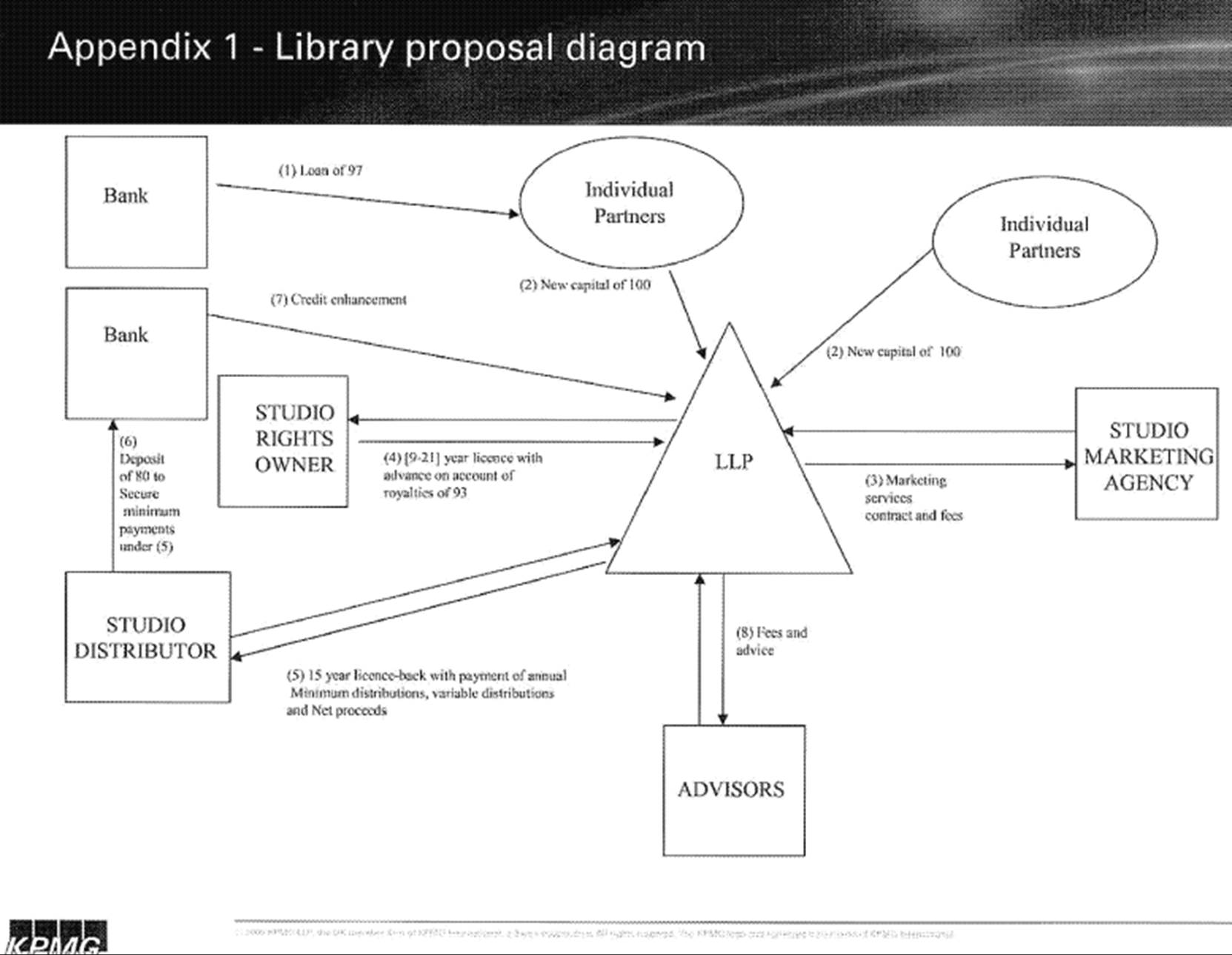

Appendix 1A: Structure diagram attached to KPMG Accounting Review.. 113

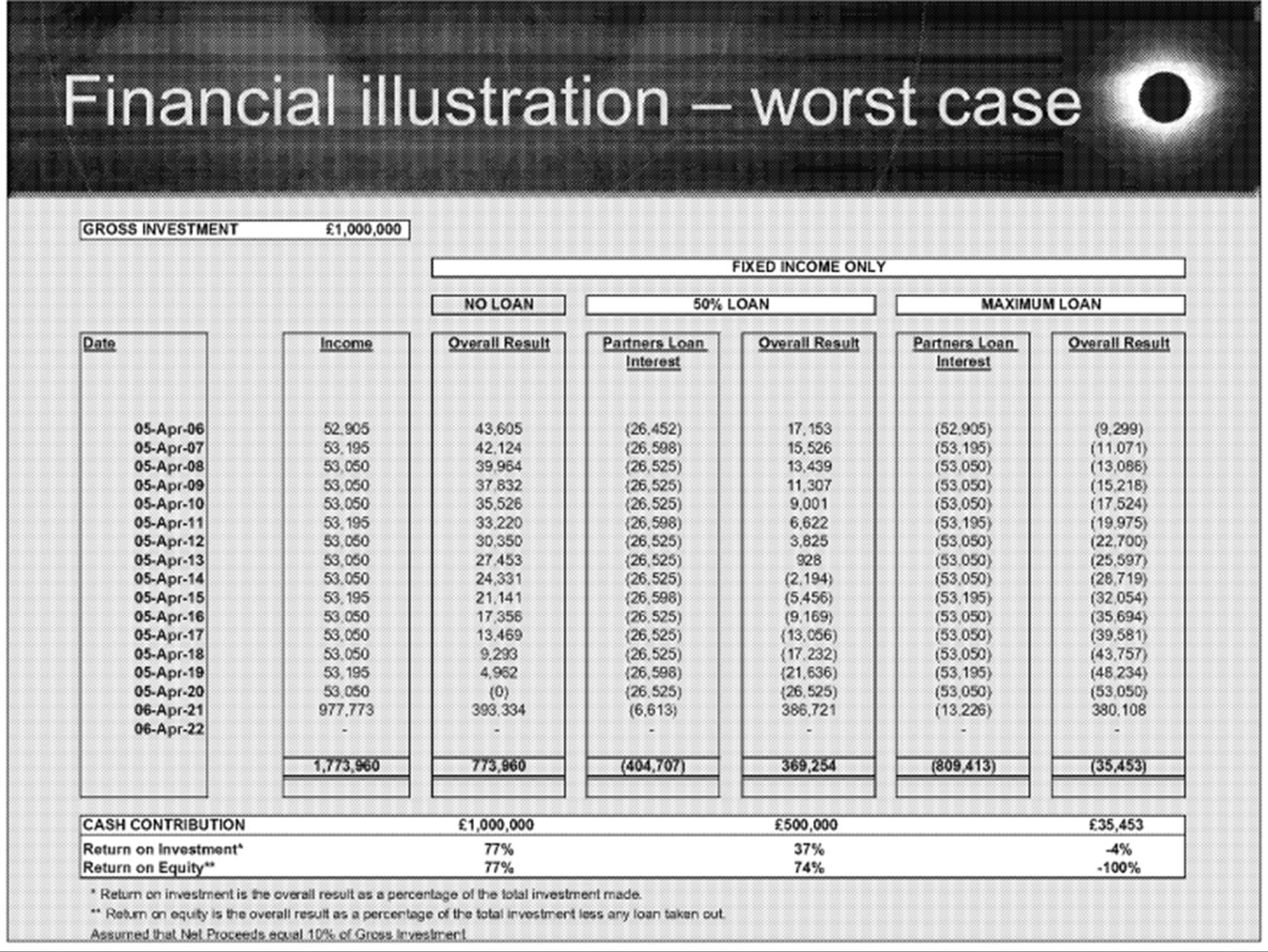

Appendix 2: Financial illustration provided to JPQC.. 114

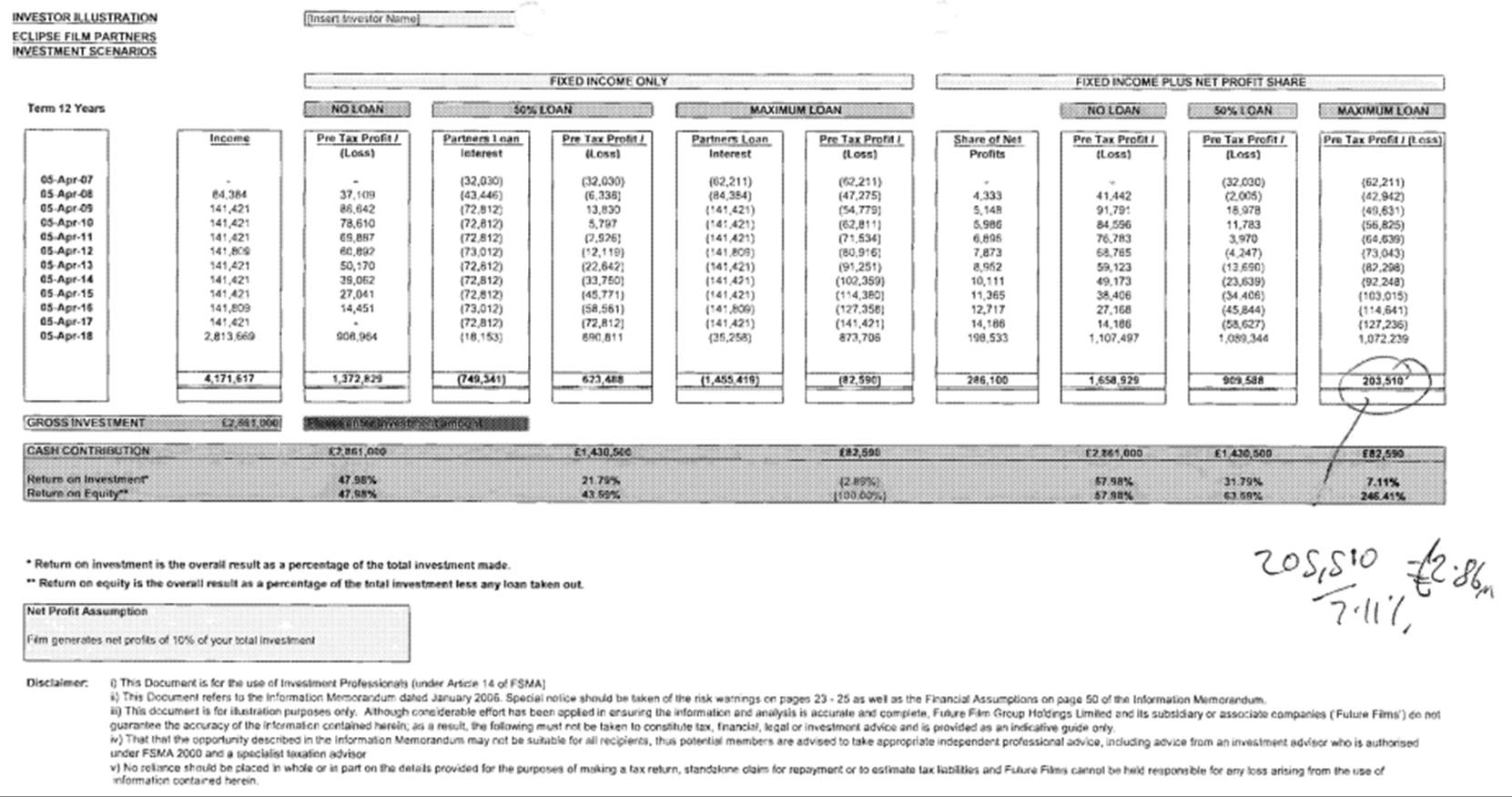

Appendix 3: Financial illustration provided to Mr Beveridge. 115

Appendix 4: Schedule 2 to Future-HSBC Agreement 116

Appendix 5: Individual Claimants' Sample Witnesses. 118

IX: Mr Christopher Bernard Upham.. 131

Appendix 6 - Losses asserted by Claimants’ Sample Witnesses. 140

Mr Justice Bright:

I: Introduction

“Nobody knows anything.”

William Goldman, ‘Adventures in the Screen Trade’ (1982)

“… nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes.”

Benjamin Franklin, letter to Jean-Baptiste Le Roy (1789)

1. William Goldman’s acidic summary of the movie business, and the exception to it required by Benjamin Franklin’s ageless quip, are at the heart of this litigation.

2. More directly, this case concerns what was known as ‘Eclipse’ - a scheme intended to enable individual UK taxpayers to defer their tax liabilities for several years, by investing in LLPs associated with the film industry. The scheme was successfully challenged by HMRC, resulting in litigation in which HMRC prevailed at every level, from the First-tier Tribunal (“FTT”), then the Upper Tribunal (“UT”), then in the Court of Appeal (together, “the HMRC Proceedings”). The result was that the investors did not succeed in deferring their tax liabilities. They claim to have suffered losses because of this, which they seek to recover from HSBC.

3. Their claims are put in a number of different ways, but the core is as follows:

(1) They invested in reliance on representations to the effect that the structure of the Eclipse scheme had been approved by a tax QC.

(2) These representations were false, in that the structure of the scheme as implemented was materially different from the structure that was the basis of the QC’s advice.

(3) These false representations were made dishonestly and/or deceitfully.

(4) HSBC knew, intended and was actively involved in all this, in the person of its employee, Mr Neil Bowman.

II: The main entities and individuals

II(i): HSBC

4. The Eclipse scheme was originally devised in 2005, chiefly by Mr Neil Bowman. Mr Bowman was a chartered accountant. He joined the firm that later became Ernst & Young in 1965 and became a tax partner in 1975. He continued in that role until 2003. He then joined HSBC Private Bank (UK) Limited - now the Defendant (“HSBC”).

5. During his time at Ernst & Young, Mr Bowman acquired a reputation for his expertise in relation to personal tax relief, in particular via structured tax products intended to benefit from tax breaks introduced by the UK Government with a view to encouraging investment in the British film industry. Several witnesses referred to Mr Bowman’s standing in this field. When he moved to HSBC, Mr Bowman was tasked with creating and originating tax-advantaged structures for high net-worth individuals or corporates, and with approaching independent film and other promoters who might wish to bring these structures to market. Mr Bowman would also go on to have a role in marketing the Eclipse scheme, to some investors and to some Independent Financial Advisers (“IFAs”). He invested in the scheme, contributing investments of his own personal capital (“Personal Contributions”) that totalled £75,199.

6. Mr Bowman’s title at HSBC was ‘Director’. Members of the team working under his direction at HSBC included Mr Guy Surtees (Assistant Director, who joined in April 2004), Mr Mark Williams (Manager, who joined in July 2006) and Ms Olivia Emmerton (a financial modeller, who joined in April 2005). The team was disbanded in September 2009, when all these individuals were made redundant. These team members all gave evidence, although Mr Bowman provided a witness statement but did not attend for cross examination.

7. Other relevant persons within HSBC include Mr Christopher Spooner, who was Group Head of Tax; and Ms Carol Boneham, who worked within the Group Tax team, reporting to Mr Spooner, and whose role at the relevant time included reviewing structured finance transactions. They both gave evidence. Also relevant were Mr Brian Bass and Ms Karina Challons, neither of whom gave evidence.

8. HSBC was represented by Mr Andrew Green KC, Mr Simon Pritchard and Mr Dominic Howells, instructed by Norton Rose Fulbright LLP.

II(ii): Future Films

9. Future Films Limited (“Future Films”) was established in 2000. Until 2018, its co-owners were Mr Tim Levy and Mr Stephen Margolis. Formally, Mr Levy’s position was CEO and Mr Margolis was Chairman, but in practice they ran the business as equals. Both of them had previous experience in the film business and, specifically, in tax-advantaged film investment transactions.

10. Other relevant persons within Future Films included Mr Leon Clarance, a specialist in tax advice, and Mr Simon Norris, whose responsibilities related to sales and administration. Also relevant is Mr David Molner of Screen Capital International Corporation (“SCI”), a consultant to Future Films and, in effect, its representative in Hollywood; and Mr Ivar Combrinck, a junior employee of SCI.

11. After they left HSBC, Mr Surtees and Ms Emmerton were employed by Future Films. Mr Surtees continued to work with Mr Margolis until about 2022.

12. Mr Margolis, Mr Surtees and Ms Emmerton all gave evidence, but there was no other evidence from anyone associated with Future Films - in particular, not from Mr Levy or Mr Molner.

13. Mr Levy, Mr Margolis and Mr Clarance all invested in the scheme. Mr Levy’s Personal Contributions totalled £2,359,879. Mr Clarance’s Personal Contributions totalled £142,916. Mr Margolis’s Personal Contributions are addressed in the context of his evidence; they totalled £840,283.

II(iii): Professional advisers to Future Films/Eclipse

14. A number of professionals gave advice to Future Films and/or to the Eclipse LLPs.

15. DLA Piper Rudnick Gray Cary UK LLP (“DLA”) were retained as tax solicitors on behalf of Future Films. The partner at DLA was Mr Simon Gough.

16. Advice was obtained from specialist tax counsel, Mr Jonathan Peacock QC. Mr Peacock QC was instructed by DLA, so in formal terms his advice was given to Future Films. However, Mr Peacock QC was selected largely on the recommendation of Mr Bowman, and HSBC attended many of the consultations at which Mr Peacock QC gave his advice. Furthermore, it was always intended that Mr Peacock QC’s advice would be referred to and relied on in the information provided to potential investors, and Mr Peacock QC was aware of this.

17. The accountants appointed by Future Films were KPMG LLP (“KPMG”). Later on, Mazars LLP (“Mazars”) were used.

II(iv): The Claimants

18. The Claimants are among the individuals who invested in Eclipse. They were represented by Mr Philip Coppel KC and Mr Zachary Kell, instructed by Edwin Coe LLP (“Edwin Coe”). They were referred to during the hearing as “the Edwin Coe Claimants”. There were previously a further 177 Claimants in a separate action, being tried together with this action, which settled during the course of the hearing. They were separately represented, by different counsel and by Stewarts Law LLP, and they were referred to during the hearing as the “Stewarts Law Claimants”.

19. Sample witnesses were selected to give evidence (“the Claimants' Sample Witnesses”): 9 for the Edwin Coe Claimants and 5 for the Stewarts Law Claimants. The settlement of the claims of the Stewarts Law Claimants means that it is not necessary for this judgment to address the merits as between the Stewarts Law Claimants and HSBC. Nevertheless, the evidence of the 5 Stewarts Law Claimants who testified before me remained admissible and relevant as between the Edwin Coe Claimants and HSBC.

III: The Eclipse structure

III(i): The essence of the Eclipse scheme

20. Many of the film transactions Mr Bowman and Future Films had been involved in before 2005 (whether with each other or separately) were sale and leaseback finance leases, often involving partnerships. After about 2004, changes in legislation and commercial pressures meant that the sale and leaseback model was no longer attractive. During 2005, Mr Bowman began to devise the Eclipse model.

21. The essence of the scheme was that investors would borrow to fund capital contributions to an LLP, and would then be entitled to set off the interest on those borrowings against their other income, for tax purposes (“Loan Interest Relief”). For the investors to be entitled to Loan Interest Relief, it was essential that the LLP be engaged in trading.

III(ii): Eclipse Tranches 1 to 5

22. Over time, there were five tranches of the Eclipse scheme. Each tranche involved one or more individual Eclipse transactions, and one or more limited liability partnerships, each named Eclipse Film Partners No. [X] [1] LLP (referred to below as “Eclipse [X]1”):

(1) Tranche 1 closed on 4 and 5 April 2006 and was comprised of Eclipse 1 - 12;

(2) Tranche 2 closed on 20 July 2006 and was comprised of Eclipse 16, 17 and 20 - 26;

(3) Tranche 3 closed on 19 and 20 March 2007 and was comprised of Eclipse 31 - 34, and 36 - 39;

(4) Tranche 4 closed on 3 April 2007 and was comprised of Eclipse 35 (only);

(5) Tranche 5 closed on 30 April 2008 and was comprised of Eclipse 40 (only).

III(iii): The roles of Future Films and of the Members

23. Each Eclipse LLP entered into a consultancy agreement (the “Partnership Consultancy Agreement”) with Future Films pursuant to which Future Films was appointed to provide certain services to the Eclipse LLP. The reality was that Future Films was in charge of all decision-making for every LLP.

24. The members of each Eclipse LLP comprised a number of individual members (the number ranging from 289 in the case of Eclipse 35, to 1 in the case of Eclipse 10) and two designated corporate members (which were companies associated with Future Films) (collectively “the Members”). Each individual who invested was liable to pay UK income tax.

25. Each Eclipse LLP was financed by capital contributed to the LLP by its individual Members. Once each LLP was established, Future Films made regular reports to the Members.

III(iv): The Eclipse Loans and the Lending Bank

26. Only a very small proportion of each Member’s capital contributions were self-financed (i.e., Personal Contributions). The vast majority of the capital contributions came from loans, arranged by Future Films and taken out by individual Members from a lending bank (the “Eclipse Loans” and the “Lending Bank”).

27. In the case of tranches 1 and 2, the Lending Bank was N.I.I.B. Group Limited (“NIIB”), a subsidiary of the Bank of Ireland (“BoI”). In the case of tranches 3 - 5, the Lending Bank was Eagle Financial and Leasing Services (UK) Limited (“Eagle”), a subsidiary of Barclays Bank Plc (“Barclays”). The sums lent to Members by the Lending Bank were borrowed by the Lending Bank from its corporate parent (i.e., BoI or Barclays, respectively).

28. The percentage of Members’ capital contributions which were borrowed from a Lending Bank varied but fell between 94% (Eclipse 35) and 99% (Eclipse 40) - in general, around 97%.

29. The terms of the Eclipse Loans arranged by Future with the Lending Bank required Members to pre-pay a proportion of the interest on their loans (with the level of the pre-payment varying across tranches and across LLPs within the same tranche: e.g., Members of Eclipse 35 were required to pre-pay 10 years’ interest on a 20-year loan, and Members of LLPs in Eclipse Tranche 1 were required to pre-pay between approximately 2 years’ interest and 11 months’ interest).

III(v): The Disney films

30. Each Eclipse LLP entered into contracts with companies in the Walt Disney group (“Disney”) for the following films, including a Licensing Agreement and a Distribution Agreement, and an agreement with a Marketing Services Provider:

(1) The LLPs in Eclipse Tranche 1 were granted a licence of rights in relation to Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest (“Pirates 2”), for a term of between 12 and 21 years;

(2) The LLPs in Eclipse Tranche 2 were granted licences in relation to Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End (“Pirates 3”), for a term of between 11 and 13 years;

(3) The LLPs in Eclipse Tranche 3 were granted licences in relation to National Treasure: Book of Secrets, for a term of between 16 and 17 years;

(4) Eclipse 35 was granted a licence in relation to both Enchanted and Underdog, for a term of 20 years; and

(5) Eclipse 40 was granted a licence in relation to Confessions of a Shopaholic, for a term of 8 years.

III(vi): The Licensing Agreement

31. In each case, the Licensing Agreement was entered into with the Disney studio corporation, Walt Disney Pictures and Television (“WDPT”), pursuant to which the LLP was granted a licence of certain specified rights to exploit and distribute film(s) produced by Disney, “but only pursuant to or as permitted by the Distribution Agreement”. As consideration for the licence, each LLP paid WDPT (a) a ‘licence fee’ (the “Licence Fee”) sourced from the Eclipse Loans, which was (nominally) divided into annual instalments but which each LLP paid in full on the closing date by way of (again nominally) an advance against its obligation to pay the annual instalments, and (b) further sums (“Variable Royalties”) which would depend on the gross revenues.

32. In relation to each LLP in each tranche of the Eclipse scheme, the Licence Fee was equal to the balance of the Members’ capital contribution after deduction of the pre-paid interest payable to the Lending Bank, and after deduction of the fee payable to Future pursuant to the Partnership Consultancy Agreement.

III(vii): Further Disney agreements: the Distributor and the MSP

33. Each LLP also entered into a Distribution Agreement with a Disney distribution company, WDPT Distribution [X] [2] LLC (the “Distributor”). Pursuant to the Distribution Agreement, each Eclipse LLP sub-licensed the self-same rights which it had licensed from WDPT (and for an identical term) to the Distributor.

34. With a view to meeting the need for the Eclipse LLPs to be carrying on a trade, each Eclipse LLP entered into an agreement named a Marketing Services Agency Agreement (the “Marketing Services Agreement”) with a marketing services provider (the “MSP”), which was a special purpose company owned and controlled by Disney, and incorporated in England and Wales. The MSP in turn entered into an agreement (the “Services Agreement”) with Disney (or a Disney affiliate) whereby Disney made staff available to the MSP in order to provide services under the Marketing Services Agreement. The services provided by the MSP under the Marketing Services Agreement related to a marketing and release campaign for each film licensed to the LLP. In this regard, a plan for each film (“the Marketing and Release Plan”) was to be prepared by or on behalf of the MSP.

III(viii): The media analysts

35. Future Films received advice as to the value of the licensing rights in the relevant films from media analysts, Kagan Media Appraisals (“Kagan”) and Salter Group LLC (“Salter Group”).

IV: The effect of the Eclipse structure

IV(i): The overall effect

36. The overall effect of this structure, under the terms of the various agreements that it comprised, was as follows.

37. As consideration for the rights sub-licensed under the Distribution Agreement, the Distributor was obliged to pay each Eclipse LLP specified sums over the term of the sub-license referred to as “Annual Ordinary Distributions”, together with sums which depended upon the gross revenues of the film(s) (“Variable Distributions”). If the licensed rights were sufficiently profitable, and as calculated by reference to a lengthy formula, the Distributor would also have to pay a share in the profits (“Contingent Receipts”, sometimes referred to as “Net Proceeds”).

38. The Annual Ordinary Distributions payable by the Distributor to each Eclipse LLP were calculated so as to be precisely sufficient to satisfy Members’ obligations under the Eclipse Loans (i.e., to pay the proportion of interest which had not been pre-paid, together with the principal). They escalated over the term of the LLP, resulting in a balloon payment in the final year which was sufficient to allow each individual Member to repay the entire balance of that Member’s Eclipse Loan.

39. The Distributor’s obligation to pay the Annual Ordinary Distributions was satisfied by the Distributor obtaining the issue of a letter of credit (the “Letter of Credit”) issued by the corporate parent of the Lending Bank, i.e., BoI (Eclipse tranches 1 and 2) or Barclays (Eclipse tranches 3 - 5) (the “Defeasance Bank”).

40. In order to obtain the issue of the Letter of Credit, the Distributor was obliged to deposit a sum with the Defeasance Bank. The sum deposited by the Distributor was sourced from the Licence Fees pre-paid by the Eclipse LLPs to Disney.

41. The sum deposited was slightly lower than the Licence Fees. The difference was retained by Disney for its own account and represented the only benefit that Disney derived from its involvement in the transaction (the “Studio Benefit”).

42. The Variable Distributions were precisely equal to the Variable Royalties. Thus, the right to receive Variable Distributions was of no net value to the LLP, because whatever might be receivable by way of Variable Distributions would be owed to Disney as Variable Royalties.

IV(ii): The effect in terms of money-flow

43. In terms of money-flow, this means that there was an essentially circular movement of funds, all of which took place at the very outset of each Eclipse transaction, upon the financial close of each LLP. This circular money-flow was wholly pre-determined by the agreements that established the Eclipse structure, and was as follows.

44. The Defeasance Bank paid the Lending Bank the sum which the Lending Bank would be lending to Members pursuant to their Eclipse Loans;

45. The Lending Bank paid Members the sums borrowed under their Eclipse Loans (into an account in their name held with Lending Bank);

46. Members (instantly and compulsorily) paid their capital contributions (which in each case comprised their Eclipse Loan plus their Personal Contribution) into an account in the name of the Eclipse LLP held with the Lending Bank;

47. The Eclipse LLP (instantly and compulsorily) paid: (a) the total amount of Members’ pre-paid interest back to the Lending Bank; (b) the sums due to Future pursuant to the Partnership Consultancy Agreement; and (c) the remainder to an account in Disney’s name with the Lending Bank as the sum due on account of the Licence Fees under the License Agreement.

48. The vast majority of the sum in (c) above was then paid (instantly and compulsorily) into an account in the Distributor’s name with the Defeasance Bank to secure the issue of the Letter of Credit, with the balance (i.e., the Studio Benefit) being at the free disposal of Disney.

49. The relevant rights were licensed by WDPT to the LLP and immediately sub-licensed by the LLP to the Distributor. The result was that the LLP was left with no meaningful interest in any film assets and retained only the right to share in Contingent Receipts.

50. The money-flow on Financial Close was, therefore, circular with the majority of the money moving pursuant to compulsory and pre-determined steps from the Defeasance Bank to the Lending Bank and back to the Defeasance Bank. The only non-circular elements of the day-one flow of money were that (a) Future retained the sum paid to it pursuant to the Partnership Consultancy Agreement, and (b) Disney retained the Studio Benefit. None of the other sums ever left the control of the Lending and Defeasance Banks (which were part of the same banking group, as already noted).

IV(iii): Profit at the level of each LLP

51. Pursuant to accounting advice obtained from KPMG and then from Mazars, each Eclipse LLP would produce its accounts by bringing into account as turnover the amounts to which it was entitled under the Distribution Agreement for that year (being the Annual Ordinary Distribution for that year, any Variable Distributions for that year, and any Contingent Receipts for that year), and including as costs of sales for that year the amount due under the Licensing Agreement for that year (or nominally due, since all of the licence fees had been prepaid on financial close), any Variable Royalties for that year, and administrative expenses for that year.

52. The effect of accounting for the transaction in this way was that each Eclipse LLP realised a profit in each year of operation. That profit was derived from the fact that the Annual Ordinary Distributions for that year exceeded the Licence Fee for that year and did so by an amount equal to the interest on Members’ Eclipse Loans (which interest was not an expense of the LLP). Broadly speaking, each Eclipse LLP would make a small profit in all years other than the final year of the term, and a large profit in the final year of the term (reflecting the fact that the Annual Ordinary Distribution in the final year of the term was structured so as to be equal to the total principal of the Members’ Eclipse Loans).

IV(iv): Loan Interest Relief for each individual Member

53. Disregarding the effects of taxation, the result of the transaction was that each individual Member of an Eclipse LLP paid his or her Personal Contribution and received in exchange the right to share in any Contingent Receipts earned by the LLP (although none were ever earned by any Eclipse LLP). The interest on Members’ Eclipse Loans was not an ‘out-of-pocket’ cost to the Members. It was satisfied by transfers from the deposit account at the Defeasance Bank to the Lending Bank.

54. Taking into account the effects of taxation, and on the hypothesis that the Eclipse LLPs were trading, each individual Member would be entitled to Loan Interest Relief in relation to the interest (including pre-paid interest) on their Eclipse Loans.

(1) This would amount to significant tax relief in the tax year in which financial close took place and subsequent years, except for the final year of each LLP’s term. This arose from Loan Interest Relief on the interest paid in those tax years, including pre-paid interest in the first year, which could be set-off against Members’ other income.

(2) In the final year, each individual Member would have a significant tax bill, arising from the large profit generated by the LLP in that year.

55. Accordingly, on the hypothesis that the Eclipse LLPs were trading, the Eclipse scheme would allow the individual Members to defer tax for a number of years.

IV(v): The cost to individual Members and the rationale

56. The cost of achieving this result comprised the upfront payment of the Personal Contribution. As long as the Letter of Credit issued by the Defeasance Bank were honoured, the net loss of each individual Member would be precisely equal to that investor’s Personal Contribution and was guaranteed to be no greater. On the other hand, the only way that the Member could do any better than this - i.e., could recover any of the Personal Contribution - would be if Contingent Receipts were received.

57. The rationale for incurring this cost was that, by deferring his tax liabilities, each Member could in the meantime invest and earn profits on the sums that would otherwise have been paid to HMRC. As long as the profits from these investments exceeded the Personal Contribution by the end of the LLP term, the Member would end up ahead.

V: The Information Memorandum and Addenda

V(i): Marketing to IFAs and to individual investors

58. The Eclipse scheme was marketed principally to IFAs, whose involvement was necessary for regulatory reasons. However, some marketing was also carried out directly to individual investors. The marketing efforts involved a few key documents and presentations. There was a subscription pack (which contained documents all investors had to complete, in order to participate). Beyond that, by far the most important marketing document was an Information Memorandum, dated 6 January 2006. This was provided to most investors, and (I infer) to all IFAs. The same Information Memorandum was used for all the Eclipse tranches, with an Addendum specific to the relevant tranche.

V(ii): Parties named in the Information Memorandum

59. The Information Memorandum was issued by a placing agent, Chiltern Corporate Finance Limited (“Chiltern”), on behalf of Future Films. It named Future Films as the promoter and Partnership Consultant, and Future Films’ name, address and contact details also appeared prominently on the back cover. It said that the Eclipse partnership was a collective investment scheme that had not been approved by the Financial Services Authority and accordingly was an unregulated scheme and could not be marketed to the general public.

60. As well as Future Films, the Information Memorandum also identified various other parties as having significant involvement:

(1) SCI was identified as the film industry consultant to Future Films.

(2) Kagan and Salter Group were identified as media analysts advising Future Films.

(3) Mr Peacock QC and DLA were identified as tax counsel and advisers to Future Films.

(4) KPMG were identified as accounting advisers to Future Films.

(5) Richards Butler were advised as media solicitors to the Eclipse LLPs.

61. There was no mention anywhere of HSBC.

V(iii): The Information Memorandum and trade/trading

62. The Information Memorandum contained numerous references to the trade that the Eclipse LLPs would be engaged in.

63. In its very first paragraph, the Information Memorandum described Eclipse as “engaging in the trade of film exploitation.” Other passages were to the same effect, including the following.

64. In a section headed “Key Highlights”, it said that Eclipse was:

“An opportunity to participate in the exploitation of new Hollywood feature franchise films produced, owned or controlled by a US Major, through an exclusive joint venturing arrangement.”

65. In a section headed “SUMMARY”, under the heading “The Proposal”, it described the LLPs as:

“… partnerships that will exploit feature films. These Partnerships will have an anticipated trading life of between 11 and 22 years.””

66. In a section headed “THE BUSINESS OF THE PARTNERSHIP”, and under the sub-heading “Strategy and Business Model”, it said:

“The Partnerships will trade in the development, production, acquisition, licensing, financing and exploitation of feature films. Initially focusing on the licensing and exploitation of film Rights to franchise films from US Majors or their affiliates, the Partnerships will structure the exploitation so that the downside risk of the films' performance is minimised whilst maintaining the ability to benefit in the potential success of the film.”

67. Under a further sub-heading in that section, it said:

“The Partnerships’ initial business proposition is the exploitation of film Rights licenced from a US Major but the overall plan is to be involved in all aspects of the film business and intends to review other film business opportunities in consultation with Members (ranging from development to financing) as part of its strategy.

The Partnership intends to contract under the Marketing Services Agency Agreement with the MSP as its agent:

• to prepare an Initial Marketing Plan; and

• to make certain arrangements for the physical exploitation of the Designated Film Rights;

• and on terms requiring that at all relevant times the services will be provided on behalf of the MSP as agent for the LLP by individuals with the necessary experience in the film exploitation business.”

V(iv): The Information Memorandum and legal advice

68. The Information Memorandum contained several passages relating to the advice of Mr Peacock QC and DLA as to the tax-effectiveness of the scheme, including the following.

69. In the section headed “THE BUSINESS OF THE PARTNERSHIP” and under the sub-heading “Advice taken regarding the Partnerships’ tax and legal treatment” the Information Memorandum said:

“Each Partnership's Business has been structured on the basis of tax advice from English solicitors (DLA Piper Gray Cary UK LLP) and from leading English tax counsel (Mr Jonathan Peacock QC) to the Partnership Consultant and the Promoter.

The Partnership Consultant and the Promoter have followed that advice and therefore expect the investment to work in the manner outlined.

While DLA Piper Gray Cary LLP and Mr Jonathan Peacock QC believe their analyses of the applicable tax law and practice to be sound, their advice is not a guarantee as to the tax treatment of any aspect of the proposal.

A copy of the settled advice note provided by Mr Jonathan Peacock QC is available to the Investment Advisers of intending Subscribers on request, from the Promoter, but neither that advice nor the advice of DLA Piper Gray Cary LLP has been or will be given to or for the benefit of Members or Subscribers.”

70. In the section headed “TAX”, under the sub-heading “Income and Capital Gains Tax Position of Individual Members”, the Information Memorandum said:

“The exploitation of Films should constitute a trade for tax purposes and, therefore, the profits and losses of the Partnership should be trading profits and losses available to the Members. It is anticipated that the Partnerships will make a profit in each year of assessment, and this is allocable to individual Partners for tax purposes in accordance with their profit sharing arrangements.”

V(v): The Information Memorandum and Contingent Receipts

71. As regards Contingent Receipts (referred to in the Information Memorandum as “Net Proceeds”), Appendix 5 to the Information Memorandum contained a series of financial illustrations, setting out the planned cashflows and showing the results to the investor on the basis of an investment of £1,000,000. This was done on several different permutations, including “Base Case” (i.e., no Contingent Receipts/Net Proceeds), “10% Net Proceeds” and “30% Net Proceeds”. The prospect of Contingent Receipts/Net Proceeds was explained as follows.

72. In a prominent section near the front headed “SUMMARY”, under the sub-heading “Financial Returns”, the Information Memorandum said that investment in films was generally considered to be risky, and referred to the “RISK WARNINGS” section, then explained the fixed returns (i.e., the Annual Ordinary Distributions). It then said:

“Additionally, the Partnership Consultant will obtain advice and valuations from the Media Analyst, based upon which the Promoter believes that the Films licenced could generate Net Proceeds.”

73. In a section headed “THE BUSINESS OF THE PARTNERSHIP” and under the sub-heading “Net Proceeds”, the Information Memorandum said (in the same terms as the draft provided to Mr Peacock QC for the consultation of 22 December 2005):

“At the date hereof, it is not possible for the Partnership Consultant to draw a sensible conclusion with respect to the probability of any Partnership receiving a Net Proceeds distribution in any year of any particular amount, as no films have been selected yet. This situation arises further because it is impossible to accurately predict box office and other revenue streams because they depend upon the viewing public. This is mitigated by the choice of major US Studio franchise films, as the track record is a good indicator (but not a guarantee) of subsequent success.

Prospective subscribers should not subscribe on the expectation that Net Proceeds (if any) would constitute a material sum.”

V(vi): The Addenda

74. The fact that Addenda would be provided was anticipated by the Information Memorandum: on its very first page, it stated that Future would produce an Addendum “once all the terms have been finalised.” The implication was that this Addendum would be available before investors had to commit.

75. The Addendum for Tranche 1 was dated 5 April 2006, i.e., the date when Tranche 1 closed. It therefore cannot have been made available to investors before they decided to invest. However, the evidence of Mr McIntyre suggests that it was provided to Tranche 1 investors soon after they invested, and that they were required to acknowledge having read and accepted it, or they would be removed from the scheme.

76. The other Addenda were issued on dates reasonably in advance of the closure of the respective Tranches. Like the Information Memorandum, the Addenda were provided to most investors, and (I infer) to all IFAs.

77. With a few immaterial variations, the Addendum for each tranche dealt with the advice of Mr Peacock QC and DLA as to the tax-effectiveness of the scheme under the heading “Advice of Tax Counsel”, as follows:

“It should be noted that owing to the need to negotiate and conclude documentation with the Studio Parties within a tight timescale it has not been possible [3] for the Partnership Consultant to have the Transaction Documents reviewed by Tax Counsel, although they have been reviewed by DLA Piper Rudnick Gray Cary LLP as tax advisers to the Partnership Consultant. It is the Partnership Consultant’s view that this is not unusual in transactions of this nature, where Counsel is not usually available at short notice and does not therefore always comment on the contractual documentation. [4] Accordingly, while the Partnership Consultant believes that the transactions have been implemented materially in accordance with the principles of the structure settled by Tax Counsel, this has not been expressly confirmed by Tax Counsel”

78. In a section headed “ADDITIONAL RISK WARNINGS AND DISCLOSURES”, under the sub-heading “LLP’s Trade”, each Addendum referred to Future’s view, having taken independent advice, that:

“… there is a real prospect the LLP Contingent Receipts Share will be payable to the LLP if the Designated Film achieves a sufficient level of success.”

79. Each Addendum referred to certain language that Disney required to be included in the Distribution Agreement and in the Waiver Letters, to the effect that Disney had made no representation as to the proceeds and that the Distributor had no obligation to distribute any film or to maximise receipts. Each Addendum then said:

“The Partnership Consultant’s view is unaffected by these statements as it believes that such protective language is a standard requirement of all US Majors (who are typically particularly concerned about the potential for litigation arising from contingent participants in their films) and bears no relationship to the actual, expected or potential performance of films in the portfolio. However, it is possible that the existence of these statements could call into question the reasonableness of the Partnership Consultant’s view. If such an argument could be successfully asserted, it could be subsequently possible to argue that the LLP is not trading with a view to profit which is the basis upon which the tax advice provided to the Partnership Consultant from its professional advisers has been obtained. Ultimately, there is a possibility that HMRC may successfully argue that the tax treatment for the Members should be different to that which they expect, including as to the availability and utilisation of any trading loss and/ or the deductibility of any interest on Members’ Loans.”

80. The Addenda also referred to the Marketing Services Agreement with the MSP:

“Each LLP has entered into a Marketing Services Agency Agreement under which the Marketing Services Provider develops individual Marketing and Release Plans for the certain territorial and/or media-specific rights to be exploited by that LLP. The Marketing Services Provider is obliged to ensure that each Marketing and Release Plan is substantially followed by the Distributor subject to the Distributor's ability to deviate from, amend and/or modify the Marketing and Release Plans pursuant to the Distribution Agreements or as otherwise approved by the Marketing Services Provider in its sole and absolute discretion from time to time, although the LLPs have had to acknowledge that the Distributor is not obliged to distribute the Designated Film in any particular territory or media.”

VI: Consultations with Mr Peacock QC

VI(i): Summary

81. From the outset, it was vital to HSBC and Future Films, alike, that legal advice be taken from tax specialists regarding the scheme, and that in due course this advice could be referred to when marketing to investors. This process began in September 2005, long before the Information Memorandum. As already noted, the tax specialists engaged were DLA and Mr Peacock QC.

82. Mr Peacock QC advised in consultations on 8 September 2005, 20 October 2005, 22 December 2005, 23 March 2006 and 29 March 2006. The information that he was given for each consultation, and the advice that he provided, altered somewhat over time, as the structure of the scheme gradually assumed its final form. However, taken overall, the explanations that he was given as to the intended structure were essentially consistent with the outline in Section III above.

83. It is not necessary to set out or even to summarise every aspect of these consultations. For the purposes of this judgment, the relevant features include the following.

VI(ii): The consultation of 8 September 2005

84. At the time of the first consultation, on 8 September 2005, the scheme under consideration was significantly different from the final scheme; not least in that the proposal was that further tax-advantaged transactions be entered into by existing partnerships that were already involved in sale and leaseback transactions. It therefore was not yet envisaged that there would be new Eclipse LLPs. However, it was envisaged (consistently with what would become the Eclipse scheme) that these partnerships would buy the licensed rights to various films, and would in return be entitled to fixed returns and, potentially to Contingent Receipts.

85. This consultation was attended by Mr Levy, Mr Clarance and Mr Norris of Future Films, by KPMG, by Mr Bowman and Mr Surtees of HSBC and by Mr Gough and Mr Michael McCormack of DLA.

86. The note of this consultation records that Mr Levy explained the role of the MSP and said that strategic decisions in relation to the proposed distribution plan (i.e., what was later referred to as the Marketing and Release Plan) would be taken by the LLP, which would be responsible for producing the distribution plan which would then be implemented by the Distributor. I infer from the note that Mr Levy said that this work would be carried out for the LLP by the MSP. Mr Peacock QC then said that he was firmly of the view that the MSP must be the agent of the LLP; and that this was important because agents act on behalf of their principals.

VI(iii): The consultation of 20 October 2005

87. The consultation on 20 October 2005 was the first that related to a scheme recognisable as Eclipse. The attendees were the same as for the consultation of 8 September 2005, save that KPMG did not attend. Mr Bowman was not identified as having attended on the note that was later produced for this consultation, but it was put to Mr Surtees in evidence, and Mr Surtees accepted, that Mr Bowman was, nevertheless, probably present.

88. For this consultation, Mr Peacock QC was given fresh written instructions which explained that it was now proposed that the relevant transactions would be entered into by new LLPs (i.e., the Eclipse LLPs).

89. The instructions stated that each LLP would acquire rights in film(s), which would be valued by an advisor (named as Kagan) and, based on this valuation, the LLP not only would make a profit based on fixed payments but would also have a reasonable possibility of earning Net Proceeds (i.e., what was later referred to as Contingent Receipts).

90. The instructions expressly stated that the MSP would be the agent of each LLP. The MSP would be controlled by or affiliated to the studio and the studio would provide to it the services of executives, probably based in the USA, and would prepare a marketing plan (i.e., what was later referred to as the Marketing and Release Plan). The plan would then be reviewed by an employee or consultant of the MSP in the UK, who would report to the MSP’s board. A decision on the plan would then be made by the MSP’s board, in the UK. The MSP would make arrangements for the exploitation of the film after the plan had been approved and would then contract with the Distribution Company.

91. Mr Peacock QC was also provided with a spreadsheet, which set out the planned cashflows. It showed that the LLP would make an overall profit, but each individual investor would make an overall loss, assuming that his Personal Contribution was largely funded by a loan and taking into account loan interest. The spreadsheet indicated a loss to the investor of £82,050, on the basis of a total investment of £1,000,000.

92. At the consultation, Mr Peacock QC said that this might prompt HMRC to question the economics of the transaction. He was told (it is not clear by whom) that the loss of £82,050 represented the worst-case position, that it was genuinely anticipated that even after financing costs were factored in the overall return would be profitable and that, if the model was amended to include Net Proceeds (i.e., Contingent Receipts), then the effect of including “these anticipated additional amounts” would be to show a cumulative profit. He was also told that it would be possible to base such models on various scenarios using historic data from previously-released franchised films. Mr Peacock QC recommended that such models should be developed, but emphasised that the data had to be “plausible”.

93. Mr Peacock QC said that there had to be careful selection of the film(s) to be acquired and sensible forecasting of anticipated returns (and these activities should be accurately and contemporaneously documented). He then said that, on the basis that there was a genuine expectation that the transaction would show a profit for the LLP (i.e., without taking account of interest on the loans of individual investors), each LLP should be considered to be carrying on a trade. Importantly, he gave this view without yet having received any plausible models to show a profit even if financing costs were factored in, per his recommendation. The effect of this part of his advice therefore appears to me to have been that, even if it could not be shown that there was a good chance of Contingent Receipts resulting in a profit for an individual investor who took out a loan, he still considered that the LLPs should be considered to be carrying on a trade.

94. Mr Peacock QC also said that it was vital that each LLP should be able to demonstrate that it was carrying out a trade through its agent, i.e. the MSP. He stressed the significance of instituting and retaining proper documentary evidence.

VI(iv): The consultation of 22 December 2005

95. The attendees on 22 December 2005 were different from that of 20 October 2005, in that KPMG attended, but there was no attendance from HSBC. Mr Peacock QC was given two sets of instructions: general instructions in relation to Eclipse, and further instructions focussing on a recent pre-budget speech. The general Eclipse instructions included a structure diagram that corresponded to the structure described in Section III above. This diagram, headed “Library Proposal Diagram”, is Appendix 1 to this judgment.

96. The general instructions referred to the fact that individual investors would have the opportunity to borrow up to 97% of their capital contribution, but then said:

“The loan offering does not form part of the proposal documentation and is only available to investors who request. It is expected that there will be investors that will invest without the loan facility. Investors may decide how much of their contribution is funded by loan finance themselves. A copy of the latest draft wording of the proposal document included as an Appendix.”

97. I should say that I find it extremely unlikely that anyone involved in preparing these instructions in fact expected that any investors would invest without using the loan facility. The attraction of the scheme was tax deferral. This could only be achieved by dint of the accounting losses that individual investors would incur by taking out loans. Without a loan and the liability to pay interest on that loan, an investor would not be able to defer any tax. That would have made participation pointless. In fact, every investor took the maximum loan available. I do not believe that this can have surprised anyone.

98. Furthermore, I suspect that Mr Peacock QC may have taken this particular part of his instructions with a pinch of salt. When advising, he said (correctly) that borrowing was optional and not an integral feature of the decision whether to undertake the trade; and (again, correctly) that it was not intended that all finance would be provided by borrowing. He did not allude to the statement in his instructions that it was expected that some investors would not borrow at all. That statement does not appear to me to have affected his advice and it is striking that it was not included in the final record of his advice, discussed below in Section VII. It must have been obvious that Future Films was seeking the advice of a leading tax QC because the fundamental purpose of the scheme was tax-related - ergo, on the basis that investors would borrow.

99. I am conscious that, in saying this, I am departing from the view expressed by the FTT that the financial illustrations provided to investors presented an attractive internal rate of return even if an investor did not wish to borrow: Eclipse Film Partners (No. 35) LLP v HMRC [2012] UKFTT 270 (TC), per the FTT at [112] and [402]. This is because I have received evidence relevant to this, which the FTT did not.

(1) The illustrations included in the Addendum for Eclipse 35 indicated an internal rate of return of 1.32% over 20 years without Contingent Receipts, and 6.14% assuming full Contingent Receipts.

(2) It must be borne in mind that investors were considering this before the 2008 financial crash, following which rates plummeted. In the pre-crash world, rates of 1.32% and even 6.14% were not attractive. In the HMRC Proceedings (all conducted post-crash, in an environment of extremely low rates) there was no evidence from investors as to the rate of return that they expected from investments. By contrast, I did receive such evidence, from several Claimants' Sample Witnesses. They wanted no less than 7% and ideally something close to 10%.

(3) I therefore do not accept that investing in Eclipse would have been attractive to anyone who had no interest in tax deferral; especially if (as they were advised in the Information Memorandum) they had not participated in the expectation that Contingent Receipts would, in fact, make any material contribution to the return on their investment. The only real attraction of the scheme was tax deferral, not investment.

(4) This means that taking out a loan was practically essential, even though it was optional in formal terms.

100. The passage from the instructions that I have quoted above stated that the current draft of the proposal document was attached as an appendix. This was a reference to the Information Memorandum, discussed below in Section V. It seems safe to assume that the Information Memorandum was duly provided to Mr Peacock QC, if only because he otherwise would surely have noticed that this appendix was missing from his instructions and would have asked for it. Furthermore, Mr Surtees emailed Mr Clarance on 20 December 2005 at Mr Bowman’s request, specifically to check that the Information Memorandum was going to be run past Mr Peacock QC; and was told that Mr Peacock QC would review it.

101. It also seems reasonable to assume that, having received it, Mr Peacock QC will have read the Information Memorandum. It was an obviously crucial document which he must have anticipated was likely to be relevant to his advice (which it was). Indeed, he knew that Future Films wanted to use his name as tax counsel, when marketing the scheme, and was being asked to confirm that he was happy with this. He therefore knew that the Information Memorandum would refer to him, and I am sure he will have been curious to know what it said about him.

102. In relation to Net Proceeds (i.e., Contingent Receipts), the draft in circulation at that time contained precisely the same direct warning against investing in the expectation of Contingent Receipts as was included in the final text (see paragraph 73 above).

103. The instructions to Mr Peacock QC for the consultation of 22 December 2005 did not draw attention to this. They did, however, refer to a schedule headed “Financial illustration”, attached to this judgment as Appendix 2. This was functionally similar to the spreadsheet that had accompanied the instructions for the consultation of 20 October 2005, but had a number of differences in terms of both format and substance, in particular as follows:

(1) It did not assume that every investor would take out the maximum loan. It illustrated the position on the basis of no loan, a 50% loan and the maximum loan.

(2) It illustrated the position both without Net Proceeds (i.e., Contingent Receipts) and with them.

(3) Whereas the spreadsheet had shown a worst-case outcome on an investment of £1,000,000 with the maximum loan to be a loss of £82,050, this illustration showed that such an investor would make a loss of £35,453 without Net Proceeds (i.e., Contingent Receipts), and a profit of £64,457 with Net Proceeds.

104. At the previous consultation of 20 October 2005, Mr Peacock QC had recommended the production of further models, but said that they must be “plausible”. Given that he had been told that the models could use historic data from actual films, it seems likely that he regarded such real-world data as one necessary element of plausibility. The “Financial illustration” schedule does not say that it was based on such data, and none of the evidence I have seen suggests that it was. It appears to have been prepared on an entirely hypothetical basis. It therefore did not comply with Mr Peacock QC’s requirement that any models should be “plausible”. Furthermore, any suggestion that the “with Net Proceeds” figures were plausible would have been very difficult to square with the warnings in respect of Net Proceeds that were included in the draft Information Memorandum.

105. The instructions included various specific questions that are not relevant to this judgment, and then asked Mr Peacock QC to confirm that he was happy for his name to be included on the Information Memorandum, and to settle a fully detailed note conforming the previous advice provided, together with the revised details set out in the instructions and the draft Information Memorandum.

106. No note was made specific to the consultation of 22 December 2005. Instead, as requested, a consolidated note was produced, dated 18 January 2006, discussed in Section V below. It combined Mr Peacock QC’s general advice on the Eclipse structure with the advice on the recent pre-budget speech. However, by comparing the note of the consultation of 20 October 2005 with the subsequent consolidated note, it is possible to work out what new advice was given on 22 December 2005 in relation to the structure in general.

107. It is not obvious that the “Financial illustration” document was discussed in detail or relied on by Mr Peacock QC. If it was, it does not seem to have made any difference to his advice. Previously, Mr Peacock QC had referred to the loss of £82,050 indicated by the spreadsheet at the consultation of 20 October 2005. That reference was removed from the consolidated note, but not replaced with anything that drew on the figures in the new “Financial illustration”. Indeed, the consolidated note made no reference to the “Financial illustration”. Rather, the consolidated note continued to recommend, in terms that had not altered from the advice given on 20 October 2005, that models should be developed, but the data used had to be plausible.

108. Accordingly, there is nothing in the consolidated note that indicates that Mr Peacock QC advised on the basis that he had received models in respect of Contingent Receipts that were based on plausible data or that the “Financial illustration” constituted such modelling. On the contrary, the text implies to the reader - as was in fact the case - that his advice was given on the basis that no such models, based on plausible data, had yet been produced.

109. Furthermore, the consolidated note again stated, in the same terms as before, that, on the basis that there was a genuine expectation that the transaction would show a profit for the LLP (i.e., without taking account of interest on the loans of individual investors), each LLP should be considered to be carrying on a trade. This part of his advice, too, seems not to have been affected by the “Financial illustration”. Just like the note of the consultation of 20 October 2005, it proceeded on the basis that it should not matter if, when interest payments were taken into account, an individual investor might expect to make a loss.

110. In short, the instructions for the consultation of 22 December 2005 contained important new material, including the following: (a) a clear statement that it was expected that some investors would not use the loan facility, and (b) the “Financial illustration” which considered the position on the basis of Contingent Receipts (as well as on the basis of there being no Contingent Receipts). However, neither of these seems to have had any effect on Mr Peacock QC’s advice.

VI(v): Subsequent consultations

111. There were further consultations with Mr Peacock QC on 23 March 2006 and 29 March 2006; and yet more consultations on various occasions after the closure of Tranche 1 on 5 April 2006. It is not necessary to record the details, because at none of these later consultations were any of the points discussed directly relevant to the issues before me.

112. However, it is relevant to note that, both before 5 April 2006 and thereafter, there were several opportunities to put transaction documents before Mr Peacock QC, and to ask him to say whether they were consistent with the structure on which he had previously advised and whether they required any alteration to his previous advice. This did not happen.

VII: The Consolidated Peacock Note of 18 January 2006

113. As noted above, the Information Memorandum stated that “the settled advice note provided by Mr Jonathan Peacock QC” was available to IFAs. In fact, not only IFAs but also several individual investors were provided with a copy of the consolidated version of Mr Peacock QC’s note, dated 18 January 2006 (“the Consolidated Peacock Note”). This was divided into 18 numbered sections.

VII(i): Section 1 - Summary of the instructions to counsel

114. The first part of the Consolidated Peacock Note summarised the instructions given to Mr Peacock QC. Among other things, in paragraphs 1.1.7 to 1.10 it set out what Mr Peacock QC had been told about the intended role of the MSP. This was all explained in terms that were consistent with the instructions for the consultation with Mr Peacock QC of 20 October 2005, set out in paragraph 90 above. This part of the Note did not record that Mr Peacock QC had been told expressly that the MSP would be the Eclipse LLP’s agent (see Section VI(iii) above, in relation to the instructions for the consultation of 20 October 2005). However, that was reflected later on, in paragraphs 3.10 and 3.11.

115. Section 1 also set out information given to Mr Peacock QC as to the sums payable to WDPT and receivable from the Distributor. In relation to Contingent Receipts, it was recorded in paragraph 1.4 that there would be a “reasonable possibility of earning Net Proceeds…” This part of the Consolidated Peacock Note must be read together with paragraph 3.3 (which I consider below).

VII(ii): Section 2 - Specific questions

116. Section 2 set out the specific questions on which Mr Peacock QC had been asked to advise. These included, first and foremost, whether he agreed with DLA’s views as to the taxation implications of the Eclipse scheme - i.e., that it would be effective at achieving tax deferral.

117. Mr Peacock QC was also asked whether his name could be used for promotion of the scheme.

VII(iii): Section 3 - Trade

118. Section 3 was, in general, the part that set out Mr Peacock QC’s views on the tax effectiveness of the scheme. It began by stating that the first issue was whether the Eclipse LLPs would be conducting a trade. In paragraph 3.2 Mr Peacock QC noted that it was genuinely expected that the Eclipse LLPs would show an overall profit. This should be sufficient to allay HMRC’s concerns about the LLP’s trading status.

VII(iv): Paragraph 3.3 - Questioning the entire transaction

119. Paragraph 3.3 began by recording Mr Peacock QC’s observation that HMRC might question the economics of the entire transaction. This observation had been made during the consultation of 20 October 2005 and had been prompted by the spreadsheet provided for that consultation, which showed a loss to each individual investor, assuming that his Personal Contribution was largely funded by a loan which incurred interest. However, the Consolidated Peacock Note did not refer to the spreadsheet or directly acknowledge how HMRC might question the economics of the entire transaction.

120. In any event, paragraph 3.3 then continued:

“Counsel considered that the important point was that it is intended that each New Partnership, at the partnership level, would make a profit. Counsel was firmly of the view that the Optional Borrowings were not an integral feature of the decision as to whether or not to undertake the trade and that the partnership activities could be carried on regardless of whether the Optional Borrowing existed. In support of this view Counsel pointed out that it was not intended that all the finance should be provided by way of Optional Borrowing.”

121. Neither here nor in Section 1 did the Consolidated Peacock Note record or refer to the fact that Mr Peacock QC had been told in his instructions for the consultation of 22 December 2005 that it was expected that there would be investors who invested without the loan facility. No-one reading the Consolidated Peacock Note would have known that Mr Peacock QC had been told this. To anyone without that knowledge, the reference to the fact that it was not intended that all the finance should be provided by optional borrowing meant, merely, that the maximum loan would be about 97%, with about 3% of the finance coming not from the Eclipse Loans but from the investors’ Personal Contributions. I cannot be sure that this is what Mr Peacock QC had in mind, although I consider that to be likely. Be that as it may, in my view it is what that particular sentence will have conveyed to any careful reader.

VII(v): Paragraph 3.3 - Information about Contingent Receipts

122. In the remainder of paragraph 3.3, the Consolidated Peacock Note then veered away from setting out Mr Peacock QC’s conclusions and instead set out information given to him during the consultations, and his response.

123. First, it said:

“It was explained to Counsel that the existing model was a base case scenario. It represented the worst case position and it was genuinely anticipated that even after financing costs were factored into the model the overall return would be profitable. It was also explained to Counsel that the existing model did not incorporate any amounts in respect of Net Proceeds Distribution. It was confirmed to Counsel that if the model was amended to include these anticipated additional amounts then, even after the financing costs had been included, the overall result would show a cumulative profit. It was explained to Counsel that it would be possible to demonstrate this by running a number of different models incorporating a number of different scenarios including historical data from previously released franchised films.”

124. This is all set out as if it was said in the course of a consultation, rather than reflecting instructions given beforehand. It is obvious that it refers to an “existing model”, which self-evidently had been provided to Mr Peacock QC before the relevant consultation.

125. It is clear from the evidence before me that this all happened at the consultation of 20 October 2005; following which further models were provided at the consultation of 22 December 2005. However, whereas the note made after the consultation of 20 October 2005 had made reference to the figures that emerged from the first model (i.e., a loss to an investor of £82,050 on the basis of an investment of £1,000,000), the Consolidated Peacock Note made no other reference to either model, nor to the figures in them.

126. Paragraph 3.3 then continued:

“Counsel emphasised the importance of ensuring that HM: Revenue and Customs did not have an opportunity to question the economics of the entire transaction and he suggested that the various alternative models should be developed. However Counsel emphasised that the data used in this modelling exercise had to be plausible, had to be able to withstand scrutiny from HM: Revenue and Customs and should include allowances for the time value of money and tax flows.”

127. This reflected more or less verbatim what Mr Peacock QC was recorded as having said at the consultation of 20 October 2005, and in the note that followed that consultation. However, it did not acknowledge that, following those remarks in October 2005, further models had in fact been provided for the consultation of 22 December 2005. As I have already noted, the implication of the fact that Mr Peacock QC’s recommendations remained extant in the Consolidated Peacock Note is that Mr Peacock QC did not regard those further models as meeting his requirements - i.e., plausible and based on historic data.

128. None of this will have been apparent to a reader of the Consolidated Peacock Note who did not have access to the evidence that I have seen. What will have been apparent to any reader, however, is that Mr Peacock QC was told that there was a “reasonable possibility” of Contingent Receipts and that it was “genuinely anticipated” that they would result in a profitable outcome for investors who took out loans; but this was all said on the basis of models that did not yet exist. Mr Peacock QC did not rely on these statements. Instead, he recommended that models showing this should be developed, using plausible historical data.

129. I highlight this because anyone who read the Consolidated Peacock Note after January 2006, and who was interested in Contingent Receipts, might have noted Mr Peacock QC’s recommendation and might have asked whether these models had, in fact, ever been developed. I have seen no evidence that any investor pursued this point. Certainly, none of the Claimants' Sample Witnesses appears to have done so.

VII(vi): Paragraphs 3.6 to 3.10 - Conclusion on “trade”

130. In the remainder of Section 3, Mr Peacock QC explained the basis on which he concluded that the scheme was effective.

131. In paragraphs 3.6 and 3.7, he said that there had to be careful selection of films and sensible forecasting of returns. It was important that these activities be documented, in order to demonstrate the activities being carried on.

132. The main foundation of Mr Peacock QC’s conclusion on the “trade” issue was set out in paragraph 3.8:

“Counsel agreed that on the premise that there is a genuine expectation that the Proposed Transaction will show an overall profit, (even though a profit is arrived at due to the fact that interest on partner's loans is not an expense of the New Partnership), each New Partnership should be considered to be carrying on a trade on a commercial basis with a view to profit. Counsel agreed that in order to substantiate the evidence of trading it is important that each New Partnership monitors the income flow from the licensing and exploitation of the Studio Film and actively considers the suitability of other acquisitions. Counsel agreed that, provided the above criteria are satisfied, each New Partnership's activities will be sufficient to lead to the conclusion that it is trading.”

133. This passage makes it clear that Mr Peacock QC was not relying on the information recorded in the second part of paragraph 3.3 as to the anticipated effect of Contingent Receipts. He came to his conclusion on trading expressly on the basis that, although the LLP would make a profit, an investor who took out a loan would not (as well as the other criteria referred to in this passage). In other words: on the basis that Contingent Receipts were ignored.

134. Paragraph 3.10 records Mr Peacock QC addressing the risk that HMRC would seek to characterise the scheme as a passive investment business. He was confident that Eclipse did not consist only of “licensing in” and “licensing out” (i.e., mere circular trading) because this was much more complex. In particular, each LLP, acting through the MSP as its agent, would devise and implement the Marketing and Release Plan. This would involve making key decisions, documented in a detailed marketing strategy. Similarly, in paragraph 3.11, he said:

“Counsel considered it vital that each New Partnership is able to demonstrate that any trade that is being conducted is being carried on by each New Partnership through its agents (i.e. the MSP).”

135. Accordingly, while section 1 of the Consolidated Peacock Note did not reflect the fact that the instructions given to Mr Peacock QC said that the MSP would be the agent of the Eclipse LLPs, it was nevertheless clear that his conclusion was based on this premise (among others), which he described as “vital”. This is consistent with the note of the consultation of 8 September 2005, where Mr Peacock QC had said that the MSP must be an agent of the LLP.

136. In paragraph 3.12, Mr Peacock QC is again recorded emphasising the importance of instituting and retaining proper documentary evidence, to ensure that the MSP would be able to demonstrate that it actually undertook the role assigned to it.

VII(vii): Paragraph 11.4 - Circular money-flow

137. The other questions considered in the remaining sections of the Consolidated Peacock Note are not directly relevant to this judgment. However, it is relevant that, in paragraph 11.4, it was recorded that the sums borrowed from the Lending Bank would be paid to Disney, then the Distributor (also a Disney company) would simultaneously place on deposit a very similar amount, to facilitate the issue of the Letter of Credit. In short, this part of the Consolidated Peacock Note was clear that there would be a circular money-flow, which would occur as soon as each Eclipse transaction closed.

138. I accept that only an unusually astute investor would be likely to pick this up from paragraph 11.4. However, this should not have been beyond the wit of the IFAs who advised most of the investors and whose job it was to consider in detail all the documents provided. The circular money-flow was in fact picked up at the time from paragraph 11.4 by one of the Claimants' Sample Witnesses - Mr Lenthall, who in many respects is a good proxy for a competent IFA.

VIII: The DLA Summary