Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

England and Wales High Court (Chancery Division) Decisions

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> England and Wales High Court (Chancery Division) Decisions >> Alliance Automotive Procurement Ltd v Auto Zatoka Spolka Z Ograniczona Odpowiedzialnoscia [2025] EWHC 1697 (Ch) (04 July 2025)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Ch/2025/1697.html

Cite as: [2025] EWHC 1697 (Ch)

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

BUSINESS AND PROPERTY

COURTS IN BIRMINGHAM

BUSINESS LIST (ChD)

33 Bull Street Birmingham, B4 6DS |

||

B e f o r e :

(Sitting as a Judge of the High Court)

____________________

| ALLIANCE AUTOMOTIVE PROCUREMENT LIMITED |

Claimant |

|

| - and - |

||

| AUTO ZATOKA SPOLKA Z OGRANICZONA ODPOWIEDZIALNOSCIA |

Defendant |

____________________

Ali Tabari (instructed by Penningtons Manches Cooper LLP) for the Claimant

Feliks Kwiatkowski (instructed by Ardens Solicitors Ltd) for the Defendant

Hearing dates: 11 June and 4 July 2025

____________________

Crown Copyright ©

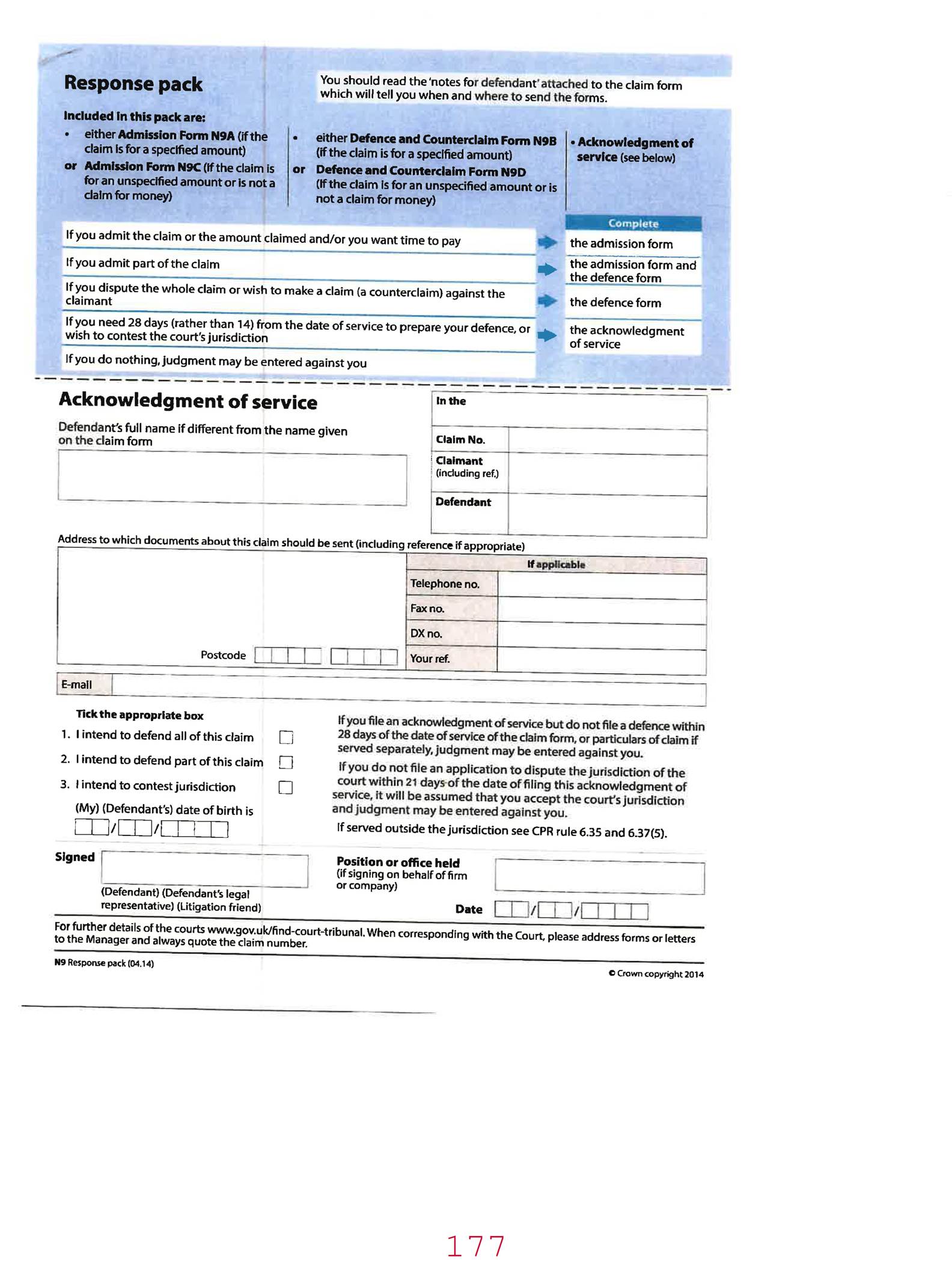

- This is my judgment following the hearing of the Defendant's application dated 11 April 2025 ("the Application") for "an order striking out the claim, and/or declaring that purported service has been ineffective, and/or declaring that the court has no jurisdiction to try the case" because the "Response Pack is identically defective in both the English and Polish versions".

- The Claimant is a company incorporated in England and Wales, and the Defendant is a company incorporated in Poland.

- The parties entered into a Supply of Goods Agreement dated 6 November 2018 ("the SGA") whereby the Claimant agreed to supply automotive parts to the Defendant.

- The SGA provided:

- On 6 November 2024, the Claimant filed at court the Claim Form and the Particulars of Claim seeking payment of Ł927,818.89 in respect of automotive parts allegedly supplied under the SGA and in respect of orders submitted between 31 July 2023 and 25 July 2024.

- It is not disputed that pursuant to Civil Procedure Rules ("CPR") r.6.33(2B)(b) the permission of the court was not required to serve the claim on the Defendant out of the jurisdiction because the claim was being made pursuant to "a contract which contained a term to the effect that the court shall have jurisdiction to determine that claim".

- CPR r.6.35(5) provides that where a claimant serves the claim form out of the jurisdiction under CPR r.6.33, the periods for responding to the claim form are set out in Practice Direction ("PD") 6B.

- PD6B provides that:

- CPR r.7.8 provides that when the particulars of claim are served on a defendant (whether they are contained in the claim form, served with it or served subsequently) they must be accompanied by (i) a form for defending the claim, (ii) a form for admitting the claim, and (iii) a form for acknowledging service.

- The Claimant's solicitors amended the time periods contained within standard Form N9 for responding to the claim so that the response pack in this particular case ("the Response Pack") stated as follows:

- It is not disputed that the Response Pack contained the following errors:

- On 11 November 2024, the Claimant's solicitors sent to the Foreign Process Section the documents for service upon the Defendant and which included the sealed Claim Form, the Particulars of Claim and the Response Pack together with certified translations. In the covering letter the Claimant's solicitors requested that "As the Defendant is based in Poland we request that service is effected pursuant to Article 5 of the Hague Convention (service via a Central Authority)."

- By order dated 24 January 2025, the time for service of the Claim Form was extended to 6 July 2025.

- The documents for service upon the Defendant were forwarded to the Ministry of Justice in Poland, which purportedly served them upon the Defendant on 3 March 2025.

- On 23 March 2025, the Defendant filed an Acknowledgment of Service recording its intention to dispute jurisdiction.

- On 11 April 2025, the Defendant filed the Application.

- The Supreme Court in Barton v Wright Hassall LLP [2018] UKSC 12 emphasised the special importance of due service of the claim even in a purely domestic setting. Giving judgment for the majority, Lord Sumption said this:

- That view was echoed even within the minority judgment, where Lord Briggs said this:

- The special importance of due service of the claim is of yet greater importance in an international context where even a simple, innocent failure to abide by internationally-agreed rules on service between nations is fatal. The rationale was summarised in Shiblaq v Sadikoglu (Application to Set Aside) (No.2) [2005] 2CLC 380 where Coleman J said this:

- It is common ground that the documents purportedly served on the Defendant were erroneous. As a matter of basic logic, proper service must include service of correctly-formulated documents, in the correct manner and in a timely fashion.

- The insertion of erroneous compliance dates in court originating process cannot be seen as a trivial error, even in the context of exclusively domestic proceedings. However, the court must view defects in international process with particular strictness. The cases relied upon by the Claimant are all domestic cases.

- If there had been an error in the service of Claim Form itself (e.g. it was not sealed, or service of it took place more than 4 months after issue) then that would likely invalidate service, as the in-time service of a sealed Claim Form is a peculiar and crucial step in its own category. However, the error identified in this case is not remotely of the same magnitude or significance, and stands in stark contrast.

- The documents served upon the Defendant contained a regular and compliant Claim Form and Particulars of Claim, together with supporting documents, as well as "forms for responding to the claim" and "any other relevant documents", as required by PD6B para 4.1. The fact that there is an error on just one of those documents does not stop it from being a document properly served.

- In any event, and even if that is wrong, this was merely a minor technical error which ought not to lead to the draconian sanction of the Claim being struck out for lack of jurisdiction. As to the guidance on this somewhat unusual issue, the White Book 2025 commentary at 7.8.1 ("Form for defence etc. must be served with particulars of claim") is relevant and instructive:

- Consistently with that pragmatic approach, in Rushworth v Harvey [2016] EWHC 1386 (QB), Leggatt J (as he then was) found that the failure to serve alongside the claim form either the particulars of claim or a response pack was no bar to the onward progress of the claim. That case was decided on the wording of the Mercantile Court Guide in force at the time, but nevertheless demonstrates the Court's generally constructive approach to these procedural issues, even when there are plain failures to comply with the requirement to serve certain documents (let alone the quibbles about the correctness of every word on those documents). Leggatt J said this:

- That approach demonstrates three things:

- In Abela v Baadarani [2013] 1 WLR 2043, Lord Clarke (with whom Lord Neuberger, Lord Reed and Lord Carnwath agreed) said this:

- Therefore, it is clear that service of a claim is concerned primarily with the process of bringing the claim to the attention of a defendant. Indeed, the Glossary to the CPR continues to define 'service' as meaning "Steps required by rules of court to bring documents used in court proceedings to a person's attention." In my judgment, the process of responding to a claim, once properly brought to the defendant's attention by way of an authorised mode of service, is related to, but distinct from, service of the claim.

- I agree with Leggatt J in Rushworth that where a claim form has been served by an authorised method of service there is no reason to imply into the CPR, when they contain no statement to this effect, a requirement that service of the claim form will be deemed not to have taken place if no response pack has been served in compliance with CPR r.7.8.

- Whilst Rushworth was concerned with service in the jurisdiction, paragraph 6 of PD6B expressly records that the time periods for responding to a claim served out of the jurisdiction begin to run "after service of the particulars of claim". There is nothing there to say that time will only begin to run from when a response pack (whether properly constituted or at all) is served.

- I am not persuaded that the court must adopt a stricter view of defects in a response pack simply because the claim is made in an international context. Again in Abela v Baadarani, Lord Sumption (with whom Lord Neuberger, Lord Reed and Lord Carnwath agreed) said this (with my emphasis added):

- CPR r.6.40 provides that service abroad may be effected by a method permitted by a civil procedure convention or treaty. The Convention on the Service Abroad of Judicial and Extrajudicial Documents in Civil or Commercial Matters ("the Hague Service Convention") is a multilateral treaty signed in The Hague on 15 November 1965 and which provides:

- The primary purpose of the Hague Service Convention is to ensure that court proceedings are served in a manner that respects the legal systems of the country involved through the designated Central Authority of the recipient country.

- In the present case, it is not disputed that (i) the court proceedings were forwarded to and served by the Ministry of Justice in Poland upon the Defendant in compliance with the Hague Service Convention, and (ii) the Defendant was through an authorised method of service made fully aware of the proceedings brought against it and of the nature of the claim made against it. Therefore, I decline to make a declaration that service of the proceedings was rendered ineffective because of errors contained in the Response Pack.

- Under CPR r.3.4(2)(c) the court may strike out a statement of case if it appears to the court that there has been a failure to comply with a rule, practice direction or court order. It is not disputed that in breach of paragraph 6.6 of PD6B the Response Pack failed to state the correct period for filing a defence.

- Under CPR r.3.9 on an application for relief from any sanction imposed for a failure to comply with any rule, practice direction or court order, the court will consider all the circumstances of the case, so as to enable it to deal justly with the application, including the need (a) for litigation to be conducted efficiently and at proportionate cost; and (b) to enforce compliance with rules, practice directions and orders.

- In Denton and others v TH White Ltd and another; Decadent Vapours Ltd v Bevan and others; Utilise TDS Ltd v Davies and others [2014] EWCA Civ 906, the Court of Appeal clarified the three stage test to be applied on an application for relief from sanctions:

- If an application is made under CPR r.3.4 to strike out for non-compliance then, whilst the Denton principles are relevant and important, the court must make a proportionality assessment and decide whether it is appropriate to strike out or not. In Walsham Chalet Park Ltd (trading as The Dream Lodge Group) v Tallington Lakes Ltd [2014] EWCA Civ 1607, Richards LJ said this:

- CPR r.11 provides that:

- It is argued on behalf of the Defendant that the admitted errors in the Response Pack ought to lead to the conclusion that the Court either lacks jurisdiction or ought not to exercise such jurisdiction it may have.

- I have already determined that the proceedings were validly served upon the Defendant notwithstanding the errors in the Response Pack. In addition, it is not properly arguable that this court has no jurisdiction when the SGA confers exclusive jurisdiction upon it. Therefore, in determining whether the court should not exercise a jurisdiction that it would otherwise have to try the claim because of the errors in the Response Pack, it strikes me that I am being invited to exercise a discretionary case management power. CPR r. 1.2 provides that the court must seek to give effect to the overriding objective when it exercises any power given to it by the Rules. As defined by CPR r.1.1, the concept of proportionality is integral to the overriding objective.

- In summary, in deciding whether to strike out the claim or decline to exercise jurisdiction over the claim because of errors in the Response Pack, the proportionality of me doing so is a highly relevant consideration.

- Considering the nature of the errors, they were:

- In the brief witness statement dated 11 April 2025 filed in support of the Application, the Defendant's solicitor stated that:

- Therefore, on 20 March 2025 and prior to the expiry of the correct time limits, the Defendant clearly knew through its solicitors of the errors in the Response Pack. In particular, the Defendant knew that the correct time for filing a defence, in the event that jurisdiction was not disputed, was 8 April 2025.

- In any event the timing of any defence was irrelevant because, on 23 March 2025, the Defendant filed the Acknowledgment of Service disputing jurisdiction. The time period for making the Application under CPR r.11(4) thereby expired on 7 April 2025. Notwithstanding that the Defendant knew that the correct time period for filing the Application was 14 days, it nevertheless filed the Application 4 days out of time on 11 April 2025, albeit within the 21 day period incorrectly stated in the Response Pack. The Claimant did not oppose the Defendant's application made in the face of the court at the start of this hearing, and which I granted, for relief from sanction to make the Application out of time.

- Whilst the Claimant has not provided any good reason for the errors contained in the Response Pack, the Defendant has not evidenced either any prejudice that it has suffered as a result of those errors or any other material disruption caused to the litigation.

- In my evaluation, the errors contained in the Response Pack were of a technical nature. They were errors of form rather than substance and as such were neither serious nor significant.

- Even if the Defendant had suffered any resulting prejudice, by for example not filing a defence in time and the Claimant having then obtained a default judgment, the proportionate response would be to set aside the default judgment and penalise the Claimant in costs.

- Under CPR r.1.3 the parties are required to help the court to further the overriding objective. The Court of Appeal has repeatedly said that the overriding objective is not furthered by parties seeking to take advantage of technical breaches/mistakes to secure a strike out.

- In Hannigan, Brooke LJ said this when allowing an appeal against a strike out for non-compliance with the CPR:

- In Denton the Court of Appeal said this:

- Rather than making the Application, the overriding objective would have been better served if the Defendant had simply pointed out to the Claimant the errors in the Response Pack and sought to agree the correct period of 35 days for the filing of a defence to the claim.

- In my judgment, it would be wholly disproportionate to strike out the claim or decline to exercise jurisdiction in circumstances where:

- The Application is dismissed.

Introduction and background

"[20.10] This agreement and any dispute or claim (including non-contractual disputes or claims) arising out of or in connection with it or its subject matter or formation shall be governed by and conducted in accordance with the law of England and Wales.

[20.11] Each party irrevocably agrees that the courts of England and Wales shall have exclusive jurisdiction to settle any dispute or claim (including non-contractual disputes or claims) arising out of or in connection with this agreement or its subject matter or formation."

a. The period for filing an acknowledgment of service under CPR Part 10 is the number of days in the accompanying Table after service of the particulars of claim – paragraph 6.3.

b. Where a defendant has filed an acknowledgement of service then the period for filing the defence under CPR Part 15 is the number of days listed in the accompanying Table plus an additional 14 days after service of the particulars of claim – paragraph 6.4(2).

In relation to Poland the number of days stated in the accompanying Table is 21 days.

10. Paragraph 6.6 of PD6B provides that "Where particulars of claim are served out of the jurisdiction any statement as to the period for responding to the claim contained in any of the forms required by rule 7.8 to accompany the particulars of claim must specify the period prescribed under rule 6.35…"

a. It stated - "If you file an acknowledgment of service but do not file a defence within 28 days of the date of service of the claim form, or particulars of claim if served separately, judgment may be entered against you." However, where an acknowledgment of service is filed the correct period for filing the defence is 21 days plus 14 days (total 35 days) after service of the particulars of claim – paragraph 6.4(2) of PD6B.

b. It stated a period within 21 days of filing the acknowledgment of service for making any application disputing jurisdiction, whereas the correct period under CPR r.11(4) for making such an application is within 14 days of filing the acknowledgment of service.

The respective arguments

Defendant

"[16.] The first point to be made is that it cannot be enough that Mr Barton's mode of service successfully brought the claim form to the attention of Berrymans. As Lord Clarke pointed out in Abela v Baadarani, this is likely to be a necessary condition for an order under CPR rule 6.15, but it is not a sufficient one. Although the purpose of service is to bring the contents of the claim form to the attention of the defendant, the manner in which this is done is also important. Rules of court must identify some formal step which can be treated as making him aware of it. This is because a bright line rule is necessary in order to determine the exact point from which time runs for the taking of further steps or the entry of judgment in default of them. Service of the claim form within its period of validity may have significant implications for the operation of any relevant limitation period, as they do in this case. Time stops running for limitation purposes when the claim form is issued. The period of validity of the claim form is therefore equivalent to an extension of the limitation period before the proceedings can effectively begin. It is important that there should be a finite limit on that extension. An order under CPR rule 6.15 necessarily has the effect of further extending it. For these reasons it has never been enough that the defendant should be aware of the contents of an originating document such as a claim form. Otherwise any unauthorised mode of service would be acceptable, notwithstanding that it fulfilled none of the other purposes of serving originating process."

"[28.] While I would not wish in any way to depart from Lord Clarke's dictum in the Abela case that the most important purpose of service is to ensure that the contents of the claim form (or other originating document) are brought to the attention of the person to be served, there is a second important general purpose. That is to notify the recipient that the claim has not merely been formulated but actually commenced as against the relevant defendant, and upon a particular day. In other words it is important that the communication of the contents of the document is by way of service, rather than, for example, just for information. This is because service is that which engages the court's jurisdiction over the recipient, and because important time consequences flow from the date of service, such as the stopping of the running of limitation periods and the starting of the running of time for the recipient's response, failing which the claimant may in appropriate cases obtain default judgment."

"[52.] In only one reported case has CPR 6.9 been considered in the context of service outside the jurisdiction. That is the decision of Lawrence Collins J. in Bas Capital Funding Corporation [2004] 1 Lloyd's Rep 652 . In that case, leave having been given to serve English proceedings in Malta, the claim form and particulars of claim were faxed and emailed and delivered by hand at the registered offices of the company and at the private address of the owner and a director of the company. All these methods were ineffective as service under English law or Maltese law. Upon an application by the claimant to dispense with service under CPR 6.9 Lawrence Collins J., having referred to Knauf UK v. British Gypsum Ltd [2002] 1 WLR 907, observed at p674–675:

"By CPR 6.9 the court may dispense with service of a document. The power under CPR 6.9 can be exercised retrospectively, but only in exceptional circumstances: Anderton v. Clwyd CC (No.2) [2002] 1 WLR 3174, 3195. The Court of Appeal distinguished the case where the claimant had not even attempted to serve a claim form in time, with the case where the claimant had made an ineffective attempt to serve, and where the defendant did not dispute that he or his legal adviser had in fact received and had his attention drawn to the claim form by a permitted method of service. In the latter case the claimant does not need to serve the claim form in order to bring it to his attention, but he has failed to comply with rules for service. The basis of the application to dispense with service is that there is no point in requiring him to go through the motions of a second attempt to complete in law what he has already achieved in fact. The defendant will not usually suffer prejudice as a result of the court dispensing with the formality of service of a document which has already come into his hands. But in the present case there has been no valid service either by Maltese law or by English law. Service by post was not attempted. The service by facsimile and email was not effective because the defendants had not previously indicated in writing that they were willing to accept service by facsimile or by e-mail: see CPR 6PD 3.1 and 3.3. Nor was there service under CPR 6.4, which provides that personal service on a company or corporation takes place by leaving it with a person holding a senior position within the company or corporation; nor under CPR 6.5(6), which only applies to documents left with a foreign company at a place where the corporation carries on its activities within the jurisdiction.

The claimants accept that the claim form has not been formally served on the defendants in accordance with Maltese law as required by CPR 6.24. But they say that the defendants have: (a) had informal service of the claim form well within the 4 month period for service; (b) received copies of all the relevant documents; (b) instructed English solicitors; and (c) taken an active part in the proceedings. Any defendant, acting sensibly and in accordance with the overriding objective, would — on receipt of the relevant documents well within the four month period and having instructed English solicitors — have waived the need for formal service or would have instructed their English solicitors to accept service in the jurisdiction."

and at 682 he concluded his judgment thus:

"At the time of the hearing of this matter service had not been effected in Malta, although of course the Company, and its Board of Administration, have had the documents since at the latest June 9, 2003. It is true that a defendant is fully entitled to insist on proper service. Proper service is particularly important in international cases, where the basis of jurisdiction is service. I would therefore hesitate before ordering service by an alternative method, or dispensing with service. But I would hope that, on mature reflection, Mr Tabona would not be advised to take any purely technical point on service."

[53.] He then adjourned determination of the application of CPR 6.9 by which time proper service could be effectively carried out or the defendant could have withdrawn objection to defective service.

[54.] In Knauf UK v. British Gypsum Ltd , supra, the relevant issue was whether an order should have been made under CPR 6.8 to permit service on German defendants' solicitors in England where, under the Hague Convention and the Anglo-German bilateral treaty, it was impermissible to serve the defendant in Germany by post, so that much time would be saved by service on the solicitors in England. At p921 Henry LJ. giving the judgment of the Court observed:

"It was argued by Peters before the judge that the Hague Convention and the Bilateral Convention were a "mandatory and exhaustive code of the proper means of service on German domiciled defendants", which therefore excluded alternative service in England. The judge did not accept that submission, pointing out that those Conventions were simply not concerned with service within the English jurisdiction. Peters did not repeat that submission on its appeal. Nevertheless, it follows in our judgment that to use rule 6.8 as a means for turning the flank of those Conventions, when it is common ground that they do not permit service by a direct and speedy method such as post, is to subvert the Conventions which govern the service rule as between claimants in England and defendants in Germany. It may be necessary to make exceptional orders for service by an alternative method where there is "good reason": but a consideration of what is common ground as to the primary method for service of English process in Germany suggests that a mere desire for speed is unlikely to amount to good reason, for else, since claimants nearly always desire speed, the alternative method would become the primary way."

[55.] With regard to the jurisdictional requirements of the Brussels Convention the judgment continued at p924:

"In the light of these considerations we would seek to sum up the issue of whether or not there was good reason in this case under rule 6.8 as follows. The application to Aikens J was put specifically on the basis that it was the best, perhaps the only means of bringing all parties into a single forum. An unusual form of service was requested, not for the sake of effecting service (for instance because of some difficulty about that), but for the sake of establishing jurisdiction over a foreign party (Peters) which was prima facie entitled to be sued in the courts of its domicile. The conventions controlling service between the United Kingdom and Germany were therefore being bypassed not in the interest of effecting service by some alternative method where the agreed method was not possible, but for the sake of establishing jurisdiction in England. Although the means used for effecting jurisdiction in England purported to find justification in the Brussels Convention's rule of strict chronological precedence and in its interest in seeing all related actions tried together, in truth such means subverted the principles of that Convention: for precedence was achieved only by taking an a priori view of where it was convenient for the litigation to be conducted. Moreover that view was taken in the absence of the defendant, who, because it was served before it even had a chance to address the court on the manner of its service, had the question of chronological precedence decided in its absence (otherwise than in the normal way mandated by the service conventions in force between the states concerned). The court's rationale for taking such action was a view as to where the litigation could best be canalised; whereas the Convention dictates other rules for deciding such questions. The devices sought were not therefore a means of finding a level playing field, but were designed to subvert the agreed principles by which the United Kingdom and Germany regulated service of process and jurisdiction.

In our judgment there cannot be a good reason for ordering service in England by an alternative method on a foreign defendant when such an order subverts, and is designed to subvert, in the absence of any difficulty about effecting service, the principles on which service and jurisdiction are regulated by agreement between the United Kingdom and its convention partners. This is not a matter of mere discretion, but of principle."

[56.] Although this decision is concerned with the prospective applicability of CPR 6.8, the underlying principles are relevant to the retrospective applicability of CPR 6.9. In particular, there is the strong disapproval of the deployment of the rule to subvert the requirements of the Hague Convention (where an objection under Article 10 has closed off a less cumbersome method of service) so as to engage the rules of the Brussels Convention as to jurisdictional precedence. I have already referred to this problem in paras 36 and 37 above. It was no doubt with this in mind that Lawrence Collins J. expressed hesitation as to the use of CPR 6.9 in Bas Capital , supra, although in that case no international service convention was involved.

[57.] The correct approach is, in my judgment, that neither CPR 6.8 (prospectively) nor CPR 6.9 (prospectively or retrospectively) should normally be used if their deployment is for the purpose of substituting a form of service or avoiding a defect in service which is inconsistent with a service convention binding as between this country and the country of service. Where it is sought to apply CPR 6.9 retrospectively, if the effect of dispensing with service is to place the defendant in the same position as he would have been in if service had not been by an impermissible method but by a method provided for by such service convention, no order should be made. The impleading of a foreign defendant which is provided for by international convention should not be effected by a fictional device aimed at circumventing the formal requirements of the relevant convention. This is an emanation of the fundamental principle of international comity and is not amenable to dilution by any feature of the Overriding Objective in CPR 1.1.

[58.] Further, even if one took the view that CPR 6.9 could be applied retrospectively to cure defective service in a case such as this, its application would not have the effect of retrospectively imposing on the defendant a duty to acknowledge service. Ex hypothesi there never has been any service such as to engage that duty at the time when it would fail to be performed. It follows that there is no way in which the retrospective application of the rule can found a basis for obtaining judgment in default.

The Claimant

"If a claimant elects to serve the claim form and particulars of claim (rather than allowing the court to do so) but fails to enclose the "response pack" for the defendant, this is a technical error which does not justify a strike out—see Hannigan v Hannigan [2000] 2 FCR 650, CA. A claimant's failure to comply with r.7.8(1) is a relevant factor in consideration of whether a default judgment should be set aside."

[4.] Mr Harvey, the defendant, instructed solicitors, Couchman Hanson. They responded on his behalf on 16 October 2014 taking two procedural points which they contended rendered service of the claim form invalid. First of all, they said that the claim form was not accompanied by a response pack, that is a form by which service may be acknowledged and an intention indicated to defend the claim. Secondly, they complained that the claim form did not contain, nor was it accompanied by, particulars of claim. Moreover, when one looks at the second page of the claim form where the claimant is expected to delete one or other of the words "attached" and "to follow" to indicate whether the particulars of claim are attached or to follow, one sees that, in the document that was served by the claimant, neither of those words had been deleted.

…….

[11.] To assess the merits of that submission, it is necessary to look at the special rules concerning the commencement of proceedings in the Mercantile Court, which are contained in CPR rule 59. As there set out, the requirements in the Mercantile Court differ in certain respects from the general requirements which apply in other courts covered by the CPR. In particular, rule 59.4 states:

"(1) If particulars of claim are not contained in or served with the claim form –

(a) the claim form must state that, if an acknowledgement of service is filed which indicates an intention to defend the claim, particulars of claim will follow;

(b) when the claim form is served, it must be accompanied by the documents specified in rule 7.8(1)…"

Those documents, I interpose, are the documents commonly referred to as the "response pack".

[12.] Rule 59.5 states:

"(1) A defendant must file an acknowledgement of service in every case.

(2) Unless paragraph (3) applies, the period for filing an acknowledgement of service is 14 days after service of the claim form…"

Paragraph (3) then refers to a situation in which the claim form is served out of the jurisdiction which is not applicable in this case.

[13.] Rule 59.7 states that Part 12 (the part of the CPR dealing with default judgment) applies to mercantile claims with certain modifications. One of those modifications, provided for at 59.7(2) is:

"If, in any Part 7 claim –

(a) the claim form has been served but no particulars of claim have been served; and

(b) the defendant has failed to file an acknowledgement of service, the claimant must make an application if he wishes to obtain a default judgment.

(3) The application may be made without notice, but the court may direct it to be served on the defendant."

[14.] Mr Clerk submitted on behalf of the defendant that service of the claim form was invalid because there had been non-compliance with rule 59.4(1)(a) and (b). That is because, in a situation where particulars of claim were not contained in or served with the claim form, the claim form had failed to state that, if an acknowledgement of service was filed, particulars of claim would follow; and there was also a breach of 59.4(1)(b) because the claim form was not accompanied by a response pack.

[15.] I accept that there was a failure to comply with those provisions of the rules. It is clear from the documents before the court that the particulars of claim were not contained in or served with the claim form. It is also apparent that the claim form did not contain a statement that, if an acknowledgement of service was filed which indicated an intention to defend the claim, particulars of claim would follow. There is a dispute about whether a response pack was served with the particulars of claim on the first occasion when it was served on 8 October 2014. The defendant's solicitors asserted in their immediate letter of response to the claim that no response pack had been provided. Although the claimant asserted the contrary, there is no documentary evidence to support that assertion and I find that he has failed to prove that a response pack was served at the same time as the claim form.

[16.] However, although there were those failures to comply with rule 59.4, neither of them, as I interpret rule 59, absolved the defendant from the requirement to file an acknowledgement of service. Rule 59.5(1) states unequivocally "a defendant must file an acknowledgement of service in every case". Furthermore, the time for doing so is stated to be 14 days after service of the claim form. Nothing in rule 59.5(2) says that time will only begin to run when a response pack is served. It is clear that a claim form had been served in this case and I see no reason to imply into the rules, in circumstances where they contain no statement to this effect, a requirement that service of the claim form will be deemed not to have taken place if rule 59.4 has not been complied with."

a. The Court will not use procedural rules as a trip-wire, and will instead look at the substance of whether service has taken place – in Hannigan at [20], the Court of Appeal described the decision it was overturning as being "about form, not substance".

b. Even when the procedural rules require the service of a form for defending/admitting or acknowledging the claim, in general the court will be prepared to overlook the fact that it has not been provided at all (which is a far worse state of affairs than a case, such as this, where all the necessary documents have been provided, but with just minor errors in one document). Such errors do not warrant striking out a claim or declining jurisdiction.

c. If the Defendant had, for example, filed and served a Defence after 30 days (instead of the wrongly-stated 28 days, but inside the true deadline of 35 days) and the Claimant had already misguidedly applied for default judgment, then the Defendant's application to set that judgment aside would clearly succeed; however, it would not lead to the Claim then being struck out, or the Court refusing jurisdiction.

Declaration that purported service has been ineffective

[37.] Service has a number of purposes but the most important is to my mind to ensure that the contents of the document served, here the claim form, is communicated to the defendant. In Olafsson v Gissurarson (No 2) [2008] EWCA Civ 152, [2008] 1 WLR 2016, para 55 I said, in a not dissimilar context, that

"… the whole purpose of service is to inform the defendant of the contents of the claim form and the nature of the claimant's case: see eg Barclays Bank of Swaziland Ltd v Hahn [1989] 1 WLR 506, 509 per Lord Brightman, and the definition of 'service' in the glossary to the CPR, which describes it as 'steps required to bring documents used in court proceedings to a person's attention...'"

I adhere to that view.

[38.] It is plain from paragraph 73 of his judgment quoted above that the judge took account of a series of factors. He said that, most importantly, it was clear that the respondent, through his advisers was fully apprised of the nature of the claim being brought. That was because, as the judge had made clear at para 60, the respondent must have been fully aware of the contents of the claim form as a result of it and the other documents having been delivered to his lawyers on 22 October in Beirut and communicated to his London solicitors and to him. As Lewison J said at para 4 of his judgment (quoted above):

"The purpose of service of proceedings, quite obviously, is to bring proceedings to the notice of a defendant. It is not about playing technical games. There is no doubt on the evidence that the defendant is fully aware of the proceedings which are sought to be brought against him, of the nature of the claims made against him and of the seriousness of the allegations."

I agree."

53. In his judgment in the Court of Appeal, Longmore LJ described the service of the English Court's process out of the jurisdiction as an "exorbitant" jurisdiction, which would be made even more exorbitant by retrospectively authorising the mode of service adopted in this case. This characterisation of the jurisdiction to allow service out is traditional, and was originally based on the notion that the service of proceedings abroad was an assertion of sovereign power over the Defendant and a corresponding interference with the sovereignty of the state in which process was served. This is no longer a realistic view of the situation. The adoption in English law of the doctrine of forum non conveniens and the accession by the United Kingdom to a number of conventions regulating the international jurisdiction of national courts, means that in the overwhelming majority of cases where service out is authorised there will have been either a contractual submission to the jurisdiction of the English court or else a substantial connection between the dispute and this country. Moreover, there is now a far greater measure of practical reciprocity than there once was. Litigation between residents of different states is a routine incident of modern commercial life. A jurisdiction similar to that exercised by the English court is now exercised by the courts of many other countries. The basic principles on which the jurisdiction is exercisable by the English courts are similar to those underlying a number of international jurisdictional conventions, notably the Brussels Convention (and corresponding regulation) and the Lugano Convention. The characterisation of the service of process abroad as an assertion of sovereignty may have been superficially plausible under the old form of writ ("We command you…"). But it is, and probably always was, in reality no more than notice of the commencement of proceedings which was necessary to enable the Defendant to decide whether and if so how to respond in his own interest. It should no longer be necessary to resort to the kind of muscular presumptions against service out which are implicit in adjectives like "exorbitant". The decision is generally a pragmatic one in the interests of the efficient conduct of litigation in an appropriate forum."

"Article 1

The present Convention shall apply in all cases, in civil or commercial matters, where there is occasion to transmit a judicial or extrajudicial document for service abroad.

This Convention shall not apply where the address of the person to be served with the document is not known.

Chapter 1 - Judicial Documents

Article 2

Each Contracting State shall designate a Central Authority which will undertake to receive requests for service coming from other Contracting States and to proceed in conformity with the provisions of Articles 3 to 6.

Each State shall organise the Central Authority in conformity with its own law.

Article 3

The authority or judicial officer competent under the law of the State in which the documents originate shall forward to the Central Authority of the State addressed a request conforming to the model annexed to the present Convention, without any requirement of legalisation or other equivalent formality.

The document to be served or a copy thereof shall be annexed to the request. The request and the document shall both be furnished in duplicate.

Article 4

If the Central Authority considers that the request does not comply with the provisions of the present Convention it shall promptly inform the applicant and specify its objections to the request.

Article 5

The Central Authority of the State addressed shall itself serve the document or shall arrange to have it served by an appropriate agency, either -

a) by a method prescribed by its internal law for the service of documents in domestic actions upon persons who are within its territory, or

b) by a particular method requested by the applicant, unless such a method is incompatible with the law of the State addressed.

Subject to sub-paragraph (b) of the first paragraph of this Article, the document may always be served by delivery to an addressee who accepts it voluntarily.

If the document is to be served under the first paragraph above, the Central Authority may require the document to be written in, or translated into, the official language or one of the official languages of the State addressed.

That part of the request, in the form attached to the present Convention, which contains a summary of the document to be served, shall be served with the document."

Strike out/declaration that the court has no jurisdiction to try the case

Applicable legal framework

a. The first stage is to identify and assess the seriousness and significance of the breach. If the breach is neither serious nor significant, the court is unlikely to need to spend much time on the second and third stages.

b. The second stage is to consider why the default occurred. If there is a good reason, the court will likely decide that relief should be granted.

c. The third stage is to evaluate all the circumstances of the case.

[44.] The judge treated the principles in Mitchell as "relevant and important" even though the question in this case was whether to impose the sanction of a strike-out for non-compliance with a court order, not whether to grant relief under CPR rule 3.9 from an existing sanction. In my judgment, that was the correct approach. The factors referred to in rule 3.9, including in particular the need to enforce compliance with court orders, are reflected in the overriding objective in rule 1.1 to which the court must seek to give effect in exercising its power in relation to an application under rule 3.4 to strike out for non-compliance with a court order. The Mitchell principles, as now restated in Denton, have a direct bearing on such an issue. It must be stressed, however, that the ultimate question for the court in deciding whether to impose the sanction of strike-out is materially different from that in deciding whether to grant relief from a sanction that has already been imposed. In a strike-out application under rule 3.4 the proportionality of the sanction itself is in issue, whereas an application under rule 3.9 for relief from sanction has to proceed on the basis that the sanction was properly imposed (see Mitchell, paragraphs 44-45). The importance of that distinction is particularly obvious where the sanction being sought is as fundamental as a strike-out. Mr Buckpitt drew our attention to the recent decision of the Supreme Court in HRH Prince Abdulaziz Bin Mishal Bin Abdulaziz Al Saud v Apex Global Management Ltd [2014] UKSC 64, at paragraph 16, where Lord Neuberger quoted with evident approval the observation of the first instance judge that "the striking out of a statement of case is one of the most powerful weapons in the court's case management armoury and should not be deployed unless its consequences can be justified".

"(1) A defendant who wishes to –

(a) dispute the court's jurisdiction to try the claim; or

(b) argue that the court should not exercise its jurisdiction

may apply to the court for an order declaring that it has no such jurisdiction or should not exercise any jurisdiction which it may have."

Analysis

a. In breach of paragraph 6.6 of PD6B, the Claimant understated the period of time for filing a defence by 7 days.

b. The Claimant overstated the period of time for making an application contesting jurisdiction by 7 days under CPR r.11(4).

"[1.] My company has conduct of this matter on behalf of the Defendant, having been instructed on 20 March 2025 and having officially gone on the court record on 23 March 2025.

[2.] I first had sight on 20 March 2025 of the claim documents which had purportedly been served on the Defendant.

[3.] On examining the claim documents, the following issues came to my attention. On the first page of the Response Pack, in the Acknowledgment of Service section, at the bottom right, there are errors in the expression of the days allowed to the Defendant to execute certain steps. The document reads-

'If you file an acknowledgment of service but do not file a defence within 28 days of the date of service of the claim form, or particulars of claim if served separately, judgment may be entered against you.

If you do not file an application to dispute the jurisdiction of the court within 21 days of the date of filing this acknowledgment of service, it will be assumed that you accept the court's jurisdiction and judgment may be entered against you.'

[5.] It is my understanding of the combined effect of CPR Parts 10, 15, 6, and Practice Direction 6B, that the days allowed are incorrectly set out in the Claimant's forms and that, contrary to item 6.6 of Practice Direction 6B, the Defendant company has not been accurately informed of its rights under the CPR and under the Hague Convention of 1965.

[6.] The Defendant accordingly seeks the relief set out in the application notice."

"[36.] Of course the proceedings should have been started on CPR form N208, as opposed to CCR Form N208, and Mr Durrell ought not to have made all the other mistakes which were attributable to his culpable lack of familiarity with the new rules. Moreover the judge was quite correct when he said that the Civil Procedure Rules were drawn to ensure that civil litigation was brought up to a higher degree of efficiency. But one must not lose sight of the fact that the overriding objective of the new procedural code is to enable the court to deal with cases justly, and this means the achievement of justice as between the litigants whose dispute it is the court's duty to resolve. In taking into account the interests of the administration of justice, the factor which appears to me to be of paramount importance in this case is that the defendants and their solicitors knew exactly what was being claimed and why it was being claimed when the quirky petition was served on them. The interests of the administration of justice would have been much better served if the defendants' solicitors had simply pointed out all the mistakes that had been made in these very early days of the new rules and Mrs Hannigan's solicitor had corrected them all quickly and agreed to indemnify both parties for all the expense unnecessarily caused by his incompetence. CPR 1.3 provides that the parties are required to help the court to further the overriding objective, and the overriding objective is not furthered by arid squabbles about technicalities such as have disfigured this litigation and eaten into the quite slender resources available to the parties."

"[40.] Litigation cannot be conducted efficiently and at proportionate cost without (a) fostering a culture of compliance with rules, practice directions and court orders, and (b) cooperation between the parties and their lawyers. This applies as much to litigation undertaken by litigants in person as it does to others. This was part of the foundation of the Jackson report. Nor should it be overlooked that CPR rule 1.3 provides that "the parties are required to help the court to further the overriding objective". Parties who opportunistically and unreasonably oppose applications for relief from sanctions take up court time and act in breach of this obligation.

[41.] We think we should make it plain that it is wholly inappropriate for litigants or their lawyers to take advantage of mistakes made by opposing parties in the hope that relief from sanctions will be denied and that they will obtain a windfall strike out or other litigation advantage. In a case where (a) the failure can be seen to be neither serious nor significant, (b) where a good reason is demonstrated, or (c) where it is otherwise obvious that relief from sanctions is appropriate, parties should agree that relief from sanctions be granted without the need for further costs to be expended in satellite litigation. The parties should in any event be ready to agree limited but reasonable extensions of time up to 28 days as envisaged by the new rule 3.8(4).

[42.] It should be very much the exceptional case where a contested application for relief from sanctions is necessary. This is for two reasons: first because compliance should become the norm, rather than the exception as it was in the past, and secondly, because the parties should work together to make sure that, in all but the most serious cases, satellite litigation is avoided even where a breach has occurred.

[43.] The court will be more ready in the future to penalise opportunism. The duty of care owed by a legal representative to his client takes account of the fact that litigants are required to help the court to further the overriding objective. Representatives should bear this important obligation to the court in mind when considering whether to advise their clients to adopt an uncooperative attitude in unreasonably refusing to agree extensions of time and in unreasonably opposing applications for relief from sanctions. It is as unacceptable for a party to try to take advantage of a minor inadvertent error, as it is for rules, orders and practice directions to be breached in the first place. Heavy costs sanctions should, therefore, be imposed on parties who behave unreasonably in refusing to agree extensions of time or unreasonably oppose applications for relief from sanctions….."

a. The Defendant having been validly served with the proceedings fully understood the claim made against it and was able to put in any defence on the substantive merits.

b. The errors in the Response Pack were not serious or significant.

c. The Defendant suffered no prejudice as a result of the errors.

d. The Defendant through solicitors was fully aware of the errors from the outset.

e. Rather than simply contacting the other side to point out the errors and to agree the correct period of 35 days for the filing of a defence, the Defendant chose instead –

i. to dispute jurisdiction in the Acknowledgment of Service (notwithstanding the clear and unambiguous exclusive jurisdiction clause contained in the SGA); and

ii. then to make the Application out of time despite having known that the correct period of time for doing so was within 14 days of filing the Acknowledgment of Service rather than the 21 days incorrectly stated in the Response Pack.

f. To strike out the claim or decline to exercise jurisdiction would allow the Defendant to obtain a windfall by opportunistically taking advantage of the Claimant's technical breach/mistake.

Conclusion