Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

England and Wales High Court (Chancery Division) Decisions

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> England and Wales High Court (Chancery Division) Decisions >> Cotham School v Bristol City Council & Anor [2025] EWHC 1382 (Ch) (10 June 2025)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Ch/2025/1382.html

Cite as: [2025] EWHC 1382 (Ch)

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

Neutral Citation Number: [2025] EWHC 1382 (Ch)

Case No: PT-2024-BRS-000009

IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE

BUSINESS AND PROPERTY COURTS IN BRISTOL

PROPERTY TRUSTS AND PROBATE LIST (ChD)

Bristol Civil Justice Centre

2 Redcliff Street, Bristol, BS1 6GR

Date: 10 June 2025

Before :

HHJ PAUL MATTHEWS

(sitting as a Judge of the High Court)

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Between :

|

|

COTHAM SCHOOL |

Claimant |

|

|

- and - |

|

|

|

(1) BRISTOL CITY COUNCIL (2) KATHARINE WELHAM |

Defendants |

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Ashley Bowes (instructed by Goodenough Ring) for the Claimant

Douglas Edwards KC (instructed by Bristol City Council Legal Department) for the First Defendant

Andrew Sharland KC (instructed by Direct Access) for the Second Defendant

Hearing dates: 27-31 January, 10 February 2025

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

JUDGMENT

This judgment was handed down remotely at 10:30 am on 10 June 2025 by circulation to the parties or their representatives by e-mail and by release to the National Archives

HHJ Paul Matthews :

INTRODUCTION

General

1. This is my judgment following the trial of this claim brought under CPR Part 8 for an order amending the commons register kept by the first defendant, Bristol City Council (“the City Council”), in its capacity as commons registration authority for Bristol. The order sought is one to delete the entry relating to land known as Stoke Lodge playing fields (“the land”), in north-west Bristol. This land was registered as a town green in August 2023, after an application for that purpose by the second defendant, who is a local resident. The claimant is an academy school, which in 2011 was granted a long lease of the playing fields by the freeholder, the City Council, for use as school playing fields.

2. Some of the following introduction to this case is based on material taken from a judgment last year concerned with procedural matters in this claim (available at [2024] EWHC 154 (Ch), [2024] JPL 955). In substance, the present claim is a contest between the claimant school and local residents. The school wishes to be able to control the land, including by the use of fences and gates, primarily to ensure the use of the land as school playing fields, but secondarily (and subject to certain restrictions) to allow it to be used for the purposes of local recreation. The latter however wish to have unrestricted access to the land at all times and object to any fences and gates, and any other restrictions imposed by the school. The land has been registered as a town green, giving various rights of access to local inhabitants. The claimant school is taking these proceedings in order to cancel that registration, if it can.

What this case is not about

3. This is a case that has aroused a great deal of passion on each side. It really matters to the parties. Each side has tried its utmost to persuade the court that it is right. Each side has put in evidence and made arguments seeking to support a conclusion that, if it should not win, the consequences will be practically apocalyptic. Inevitably, one side (at least) will be disappointed by this judgment. But these consequentialist arguments, though they may be useful in the political arena, are of little assistance to a court of law.

4. In the present case, if the land is held to satisfy the test for a town or village green, the local residents will succeed, and any fences, gates and other restrictions may well prove impossible. The school says that, in that case, it will be unable to use the land for the purposes of school playing fields, for security, health and safety reasons (among others). In this litigation, however, the court is not required to decide whether the school is right about that. More importantly, it is not required to decide whether use by the school is more important or less important, or more or less in the public interest, than use by local residents. That is a political decision, which Parliament has made in enacting the relevant legislation. By virtue of that legislation, use of a certain kind and quality by certain people for a certain period enables the creation of a public right against the landowner. Use which is less than that does not. The matter is binary.

5. Either this case satisfies the requirements of that legislation, in which case the local residents succeed, or it does not, in which case the school succeeds, or at least may do so. The court’s only functions are to decide whether the land concerned at the date of registration was, or was not, within the legal definition of a town or village green, and, if it was not, whether it is “just” to amend the register. These are questions of mixed fact and law. The political and consequential issues raised by the facts of this case are wholly outside the court’s jurisdiction. The lawyers involved know this, but the public needs to know it too. I trust that, if the media report this case, they will make this clear.

The position of the first defendant

6. My judgment in this case last year was concerned in part with the position of the first defendant, which was (and is) both the registration authority under the relevant legislation and also the freeholder of the land concerned. It had originally sought to play two distinct roles in the litigation, and filed two acknowledgments of service, one in one capacity and one in the other. I held that it could not do this, and could appear on the record in this case once only. In the event, the first defendant chose to oppose the order sought by the claimant, and appeared by leading counsel at the trial. It did not call any evidence of its own, and did not seek to cross-examine any of the witnesses who were called. But it did make submissions on the law, in defence of the authority’s decision to register the land as a town green. It did not adopt a neutral position.

7. In TW Logistics Ltd v Essex County Council [2017] Ch 310, a similar claim to the present was brought by a landowner for the rectification of the register, against the registration authority. In pre-trial correspondence, the defendant’s solicitors said:

“it is accepted that a registration authority … should maintain a strictly neutral stance in the exercise of its statutory function and we agree that it should not and confirm that it has not predisposed itself either for or against continued registration … Our client’s position is one of neutrality and will continue to remain so.”

8. Subsequently, the claimant argued that in fact the defendant had not adopted a neutral position. Barling J summarised the defendant’s position in this way:

“39. In its skeleton argument, Essex CC states that, whilst seeking to uphold its decision to register the Land on the evidence before the Inspector, it would take a neutral stance in relation to the additional evidence submitted in these proceedings, including the expert evidence of Mr Hibbert. Pursuant to that stricture, Mr Sharland did not cross-examine any of the witnesses called, nor did Essex CC call any evidence itself. Mr Sharland did not make submissions in respect of TWL’s two new grounds of challenge, as they were not advanced before the Inspector and are, at least to some extent, based on the new evidence.”

9. After considering authorities, he concluded

“41. It seems to me that there is a danger of elevating what may be an appropriate position for such an authority to take depending on the circumstances, into a principle that it is under a duty to apply a self-denying ordinance. I see nothing in the Leeds case (Leeds Group plc v Leeds City Council [2010] EWHC 810 (Ch), [2011] Ch 363, CA) nor in the dicta in [Oxfordshire County Council v Oxford City Council] [2006] 2 AC 674 which denies the authority the right to take a more active role in section 14 proceedings, should it wish to do so. Lord Hoffmann simply referred to the absence of a duty on the part of the registration authority to investigate or to adduce new evidence.

42. Without having heard full argument, I am inclined to the view that the fact that the authority has a quasi-judicial role at the decision-making/registration stage does not and should not preclude it, where appropriate, from fully defending its decision in the context of a subsequent section 14 claim, including by challenging new evidence and new submissions and/or by calling new evidence of its own. By the same token, if, having heard new evidence and submissions, an authority were to take the view that its original decision was wrong, it would surely not be right for it to defend it.”

10. The point was not discussed when the case was taken to the Court of Appeal ([2019] Ch 243) or the Supreme Court ([2021] AC 1050). The approach of Barling J was not challenged in the present case, and I have not heard any argument, or had to rule upon it. Whether it is right or not can be left to another case where it arises as an issue between the parties. Whether it might affect questions relating to costs in this case is another matter, but that does not arise at this stage, and indeed may never arise.

BACKGROUND

History of Stoke Lodge

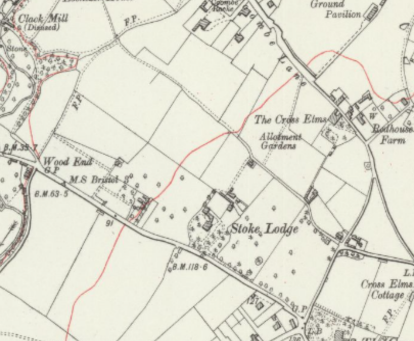

11. Stoke Bishop is a very old settlement. It is referred to in the Domesday Book of 1086 as Stoche. In old English, “stoc” meant a dwelling or a place (like “stow” in Brigstowe, later Bristol). Under the feudal system, it was held of the king by the Bishop of Worcester (in whose ecclesiastical diocese it then lay, and who also owned the monastery at nearby Westbury on Trym). No doubt that is why it became known as Stoke Bishop. Until just after the Second World War, the land with which this case is concerned formed part of the grounds belonging to a substantial residential property known as Stoke Lodge. This had been built in 1838 on land which was formerly part of the Kingsweston estate, based on Kings Weston House (designed by Sir John Vanbrugh) near Lawrence Weston. Once built, the new property was occupied successively by a number of well-to-do local families, including at one time a scion of the well-known Fry family, chocolate makers. When it was originally built, Stoke Lodge lay outside the boundaries of Bristol, in Gloucestershire. But by the end of the nineteenth century Bristol’s boundaries had expanded, and Stoke Lodge was by then within them.

12. I set out below the relevant part of an Ordnance Survey map revised in 1912. This shows Stoke Lodge before the First World War. North is to the top of the map. It will be seen that when surveyed, the area was little built up. I make clear that I have included this map only to explain the historical development of the area, and do not rely on it in any way in deciding the issues that arise in this case.

13. A revision of the map in 1938 (published in 1944), set out below, shows that the modern urban pattern was taking shape. Again, this is included only to illustrate the historical development of the area, and not for any further purpose.

14. After the Second World War, part of the land in question (about 5.5 acres) was acquired from the then owner (Miss Emily Butlin) by the council of the county borough of Bristol, the successor to Bristol Corporation under the Local Government Act 1888. The acquisition was initially for temporary housing, but thereafter the land was appropriated to education purposes. (“Appropriation” is a formal process by which local authority assets are dedicated to a specific statutory purpose - or rededicated from one purpose to another: see currently section 122(1) of the Local Government Act 1972, set out later.) The remainder - about 16.5 acres according to documents I have seen, but the Inspector in 2016 put it at 22 acres - was acquired from Miss Emily Butlin, again for education purposes, by the county borough of Bristol in 1947.

15. In 1974, when local government in England and Wales was reorganised, pursuant to the Local Government Act 1972, the land was vested in the county borough’s successor for education purposes, Avon County Council (the city of Bristol being demoted from county status for the first time since 1373, and becoming merely a district within the new county). But, in 1996, when, pursuant to the Local Government Act 1992, s 17, and the Avon (Structural Change) Order 1995, that county council ceased to exist, and Bristol became a unitary authority (styled the “City and County of Bristol”), the land was vested in that unitary authority - the City Council, by the Local Government Changes For England (Property Transfer and Transitional Payments) Regulations 1995, regulation 6. Regulation 11 of those regulations provided for the transfer of all the “functions” of an abolished authority to the transferee authority for that district. “Functions” is not defined, but appears to refer to “all the duties and powers of a local authority; the sum total of the activities Parliament has entrusted to it” Hazell v Hammersmith & Fulham LBC [1992] 2 AC 1, 29.

16. I must note also regulation 12 of those regulations, to which I shall return. This provided:

“12.—(1) All contracts, deeds, bonds, agreements, licences and other instruments subsisting in favour of, or against, and all notices in force which were given, or have effect as if given, by or to, a relevant authority in respect of any transferred matters shall be of full force and effect in favour of, or against, the body to whom such matters are transferred.”

Photograph and plan

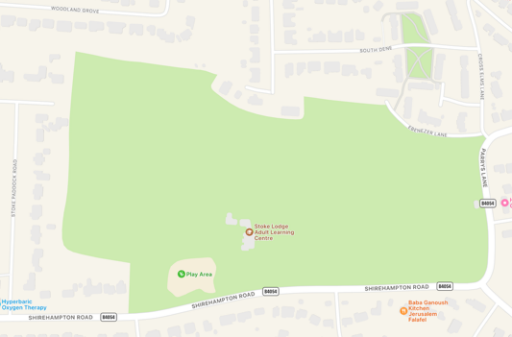

17. I set out below first a modern aerial photograph and then a modern plan of the relevant land, each taken from Google Maps. They have been re-oriented, so that north is to the north-west corner of both. Again, they are for expository purposes only, and have no legal significance.

18. Approximately in the centre of the lower half of both the photograph and the plan is the old Stoke Lodge House. To the west of the house is a children’s play area, constructed in recent years. As will be made clear shortly, not all of the open land shown above was leased by the City Council to the claimant school. To add another layer of complexity, the land the subject of the registration is different again, although the leased land and the registered land largely overlap. I should record that in the present case I had the great advantage of a site visit on the first day of the trial, accompanied by counsel. I record here that I visited a second time, on my own, shortly before circulating my draft judgment, in order to make sure I had correctly remembered what I saw on the first occasion.

Cotham School

19. Stoke Lodge House became a nursery nurses’ college, and subsequently an adult education centre, which it remains today. It is a Grade II listed building. The land surrounding it was used for a variety of purposes, including as the playing fields for Fairfield Grammar School, then a local authority school in the Montpelier district of Bristol (a school attended in much earlier days by one Archie Leach, better known later as Cary Grant). In September 2000, the then Cotham Grammar School, another local authority school, took over the use of the land from Fairfield for its own playing fields. (Cotham Grammar became a comprehensive school the following year.) The land is however not in the vicinity of the main school site, but lies some three miles away to its north-west. Following the enactment of the Academies Act 2010, Cotham School applied for and obtained academy status, as from 1 September 2011. On obtaining that status, it acquired independent legal personality, as a company limited by guarantee. It also acquired a long lease of the school buildings from the City Council, and henceforward obtained its funding from central government. The City Council as local education authority ceased to have any direct responsibility for the school, though of course it remains the school’s lessor (in popular terms, landlord).

20. The funding agreement dated 1 September 2022 between the claimant and the Secretary of State requires the school to be conducted in accordance with the company’s memorandum and articles, which cannot be amended without the consent of the Secretary of State. It also requires a restriction to be entered in the land register in relation to its land assets, prohibiting any disposition of such assets without the consent of the Secretary of State. The claimant is also a charity, exempt from registration with the Charity Commissioners. The current articles of association of the company include a provision at clause 6.1 restricting the use of the claimant’s resources:

“The income and property of the Academy Trust shall be applied solely towards the promotion of the Objects.”

The lease

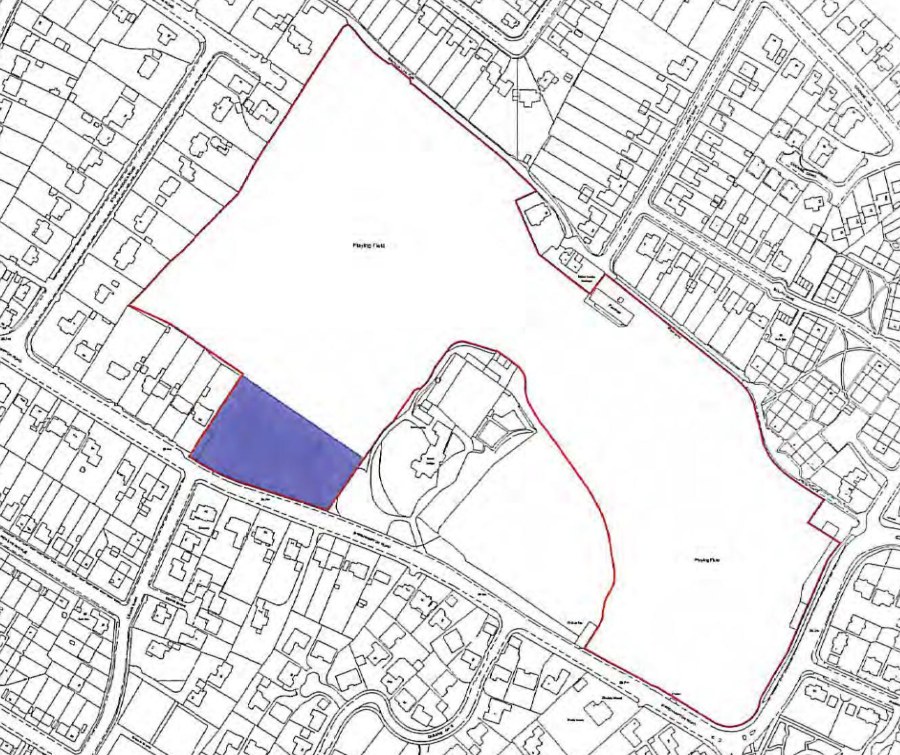

21. On 31 August 2011, the City Council granted a long lease (125 years) to the claimant of the land as school playing fields. The plan to the lease (with north at the top) shows the area of land demised:

22. The demised area is that surrounded by the red line. It will be seen that it includes an area coloured blue in the southwest corner (though the lease itself calls the colour ‘purple’). This is the subject of an option for the City Council to break the lease, but only in respect of that part of the land. It will also be seen that a part of the grounds to the southeast of Stoke Lodge House is not included in the demise. This area is known as “the Arboretum”. It is planted with trees and shrubs, and has never been used by the claimant for its educational purposes. It appears quite distinctly on the photograph included above, with more trees visible, and a different shade of green, compared to the rest of the grounds. What this means is that the first defendant holds part of its fee simple (freehold) estate in the land in possession (the Arboretum) but the remainder of it in reversion.

23. The lease itself includes the following provisions:

“1. Definitions and Interpretation

1.1. In this Lease unless the context otherwise requires the following words and expressions shall have the following meanings:

[ … ]

‘Funding Agreement’ (a) an agreement pursuant to section 1 of the Academies Act 2010 made between (1) the Secretary of State for Education and (2) the Tenant …

[ … ]

‘Plan 1’ the plan annexed to this Lease and marked Plan 1;

[ … ]

‘Property’ the property described in Part 1 Schedule 1 [which refers to the land part of Stoke Lodge Playing Fields “being part of the freehold land registered at the Land Registry under title BL 100993 and shown edged red on the Plan 1”]

‘Rent’ a peppercorn;

[ … ]

Term 125 years from and including the Term Commencement Date

Term Commencement Date

1 September 2011

[ … ]

2. Demise Rents and Other Payments

2.1. The Landlord demises the Property to the Tenant for the Term (subject to the provisions for early termination contained in this Lease) together with the easements and rights specified in Schedule 2 excepted and reserved unto the Landlord and all other persons authorised by the Landlord from time to time during the Term the easements and rights specified in Schedule 3 and subject also to all existing rights and use of the Property including use by the community the Tenant paying therefor by way of rent throughout the Term without any deduction counterclaim or set off (whether legal or equitable) of any nature whatsoever:–

2.1.1 the Rent (if demanded);

2.1.2 all other sums (including VAT) due under this Lease from the Tenant to the landlord.

[ … ]

3. Tenant’s Covenant

The Tenant covenants with the Landlord as follows:-

[With a few exceptions, here I simply summarise the headings of the subclauses]

3.1 [Rent and Payments]

To pay the Rent and all other sums reserved as rent by this Lease at the times and in the manner at and in which they are reserved in this Lease.

3.2 [Outgoings]

3.3 [Repair and Upkeep]

3.4 [Access of Landlord and Notice to Repair]

3.5 [Alterations and Additions]

3.6 [Signs and Advertisements]

3.7 [Statutory Obligations]

3.8 [Yield up]

3.9 [Use]

[ … ]

3.9.3. … not to use the Property otherwise than

(a) for the purposes of the provision of educational services by the Tenant (as set out in any charitable objects of and in accordance with the memorandum and articles association of the Tenant from time to time); and

(b) for community, fundraising and recreational purposes which are ancillary to the use permitted under clause 3.9.3 (a).

[ … ]

3.10 [Planning and Environmental Matters]

3.11 [Notices]

3.12 [Dealings]

3.12.1. Not to part with or share the possession or occupation of the whole or any part or parts of the Property …

[ … ]

3.12.3. Subject to the provisions of sub-clause 3.12.4, not to assign or transfer any part or parts or the whole of the Property;

3.12.4. The Tenant is permitted to assign or transfer the whole of the Property to a successor charitable or public body where the Secretary of State has given approval to such an assignment or transfer;

3.12.5. Not to underlet the whole of the Property and not without the Landlord’s consent (not to be unreasonably withheld) to underlet any part or parts of the Property for a term in excess of 5 years but excepting that the Tenant may without the consent of the Landlord allow other parties to use the Property for temporary sessional lettings and for the avoidance of doubt the Tenant may enter into a maintenance scheme which allows a third party to act as an agent on the Tenant’s behalf in relation to such lettings

[ … ]

3.12.6. Not to charge the whole or any part or parts of the Property

3.13 [Rights of Light and Encroachments]

Not to obstruct any windows or lights belonging to the Property nor to permit any encroachment upon the Property which might be or become a detriment to the Landlord and in case any encroachment is made or attempted to be made to give immediate notice of it to the Landlord.

3.14 [Indemnity]

3.15 [Costs]

3.16 [VAT]

3.17 [Interest on Arrears]

3.18 [Landlord’s Property]

4. Landlord’s Covenants

The Landlord covenants with the Tenant

4.1 Quiet Enjoyment

That the Tenant may peaceably and quietly hold and enjoy the Property during the Term without any interruption or disturbance by the Landlord or any person rightfully claiming through or under the Landlord.

[ … ]

6. Provisos

6.1 Re-Entry

Where there occurs a breach by the Tenant of Clause 3.9 and/or 5.1.2 of this Lease and the Landlord has served written notice specifying such breach and the remedial action required by the Tenant and if within a reasonable period (taking account of the breach complained of) the Tenant has not taken steps to remedy such breach or the Tenant is dissolved or struck off or removed from the Register of Companies or otherwise ceases to exist then it is lawful for the Landlord or any person authorised by the Landlord at any time afterwards to re-enter upon the Property or any part of it in the name of the whole and thereupon the Term absolutely determines without prejudice to any right of action of the Landlord in respect of any breach of the Tenant’s obligations contained in this Lease.

[ … ]

6.7. Termination

6.7.1. This Lease shall automatically determine on the termination of the Funding Agreement in circumstances where there is no other Funding Agreement in existence.

[ … ]

6.7.4. On the termination of this Lease under Clause 6.7.1 everything contained in the Lease ceases and determines but without prejudice to any claim by either party against the other in respect of any antecedent breach of any obligation contained in the Lease.

7. Break Clause

In the event that the Tenant finds suitable alternative playing fields … then subject to the Tenant giving the Landlord no less than three (3) months’ written notice the Tenant may determine this lease at any time during the Term hereby created … but without prejudice to the respective rights of either party in respect of any antecedent claim of breach of covenant

8. Landlord’s Powers

8.1. The Landlord enters into this Lease pursuant to its powers under sections 111 120 122 and 123 of the Local Government Act 1972 the Education Act 1996 section 2 of the Local Government Act 2000 and all other powers so enabling and warrants that it has full power to enter into this Lease and to perform all obligations on its part herein contained.

8.2. Nothing in this Lease shall fetter the Landlord in the proper performance of its statutory functions.

[ … ]

11. Landlord’s option to determine

11.1 If at any time during the Term the part of the Property shown coloured purple on the plan 1 to the Lease (“the Surrender Land”) is required by the Landlord for the provision of public facilities and provided always that the Property then left to the Tenant is sufficient to provide outdoor educational facilities as deemed appropriate in accordance with the number of children in accordance with any relevant legislation and national guidance then if

11.1.1 the Landlord shall give to the Tenant not less than three (3) months previous notice in writing; and

11.1.2 the Landlord seeks representations from, and consults in a responsible manner with, nearby residents or local interest groups in relation to the proposed provision of public facilities

then immediately after the expiration of the said notice period this Lease and everything in this Lease ceases and determines in relation to the Surrender Land but without prejudice to any claim by either party against the other in respect of and antecedent breach of any obligation contained in this Lease

[ … ]”.

24. Apart from the terms of the lease themselves, I note that, under section 13 of and Sch 1 to the Academies Act 2010, the Secretary of State has power to give directions for transferring academy school land to others (including local authorities) in various circumstances. These include, for example, the cases where the school ceases to be an academy or to occupy the land for its purposes. The effect of this in substance is that the land, even though the subject of a 125-year lease, can be used only for the purposes of an academy school. A lease of land to a different kind of school (eg a private school) would not be subject to these statutory provisions.

First application for registration

25. On 7 March 2011, whilst the school was still a local authority school, a local resident called David Mayer made an application to register the land as a town or village green under section 15 of the Commons Act 2006. (He actually did so in the name of a community group called “Save Stoke Lodge Parkland”.) As I have said, the commons registration authority for Bristol is the City Council. But the City Council has delegated its functions as such authority to a committee of itself, namely, the Public Rights of Way and Greens Committee (“PROWG”), under section 101(1)(a) of the Local Government Act 1972. This provides that “a local authority may arrange for the discharge of any of their functions … by a committee … of the authority”. On 25 November 2011, the claimant lodged an objection to the application. The objection acknowledged informal use of the land by local residents, but stated that this had not been encouraged by the claimant, nor acknowledged as being “as of right”.

Appointment of an inspector, and his first report

26. As appears to be common practice in such cases (see R (Whitmey) v Commons Commissioners [2004] EWCA Civ 951, [29]; Oxfordshire County Council v Oxford City Council [2006] 2 AC 674, [29], HL), the committee appointed a barrister, Mr Philip Petchey, experienced in this area of the law to conduct a (non-statutory) public inquiry to ascertain the facts, to report on the application, and to recommend whether it should be accepted or rejected. Mr Petchey issued directions for such an inquiry in August 2012. However, subsequently Mr Petchey advised the committee that in his view it was not necessary to hold a public inquiry, but that the matter could be determined on the basis of written representations. The committee agreed, and Mr Petchey received and considered such representations.

27. On 22 May 2013, Mr Petchey issued his report, recommending that the land be registered as a town or village green. In part this recommendation was based on the decision of the Court of Appeal in a case concerned with the doctrine of statutory incompatibility in town and village green cases, which I discuss later in this judgment. In part, the decision was based on the inspector’s perception as to the signs on the land, which on the material before him he judged insufficient to negate user “as of right”.

28. However, the land was not in fact registered at that time. It appears that the City Council as landowner changed its position, and now considered that there should be a public inquiry to hear evidence about notices. And the claimant considered that there should be one to hear evidence about the use of the land by the school and sports clubs. It then became known that there was to be an appeal to the Supreme Court in the statutory incompatibility case. It was decided to wait for the decision in that case to be handed down. That was done on 25 February 2015. The appeal was allowed and the decision of the Court of Appeal reversed. As a result, after considering submissions, Mr Petchey decided that it was appropriate to hold a public inquiry. The committee agreed to this.

The public inquiry, and the second report

29. A pre-inquiry meeting was held in February 2016, and directions were issued in March 2016. The inquiry itself sat in June and July 2016. It sat for 8 days, and heard 28 witnesses. The applicant, the school, local residents and the City Council all participated in this. The applicant Mr Mayer appeared in person. The school and the City Council were represented by counsel, the former by Richard Ground QC and Ashley Bowes, and the latter by Leslie Blohm QC. Both the school and the City Council advanced the case that the land should not be registered because (inter alia) the use of the land by the public was contentious. (I take this opportunity to say that Mr Blohm QC is now himself a judge, also sitting in Bristol, but also that he and I have obviously not discussed this matter.)

30. The inspector’s second report, dated 14 October 2016, this time recommended that the application be rejected. City Council officials subsequently produced a report recommending that the authority reject the application, for the reasons given by Mr Petchey. It also recommended that, if it were to approve the application, it should provide reasons for its decision. But, on 12 December 2016, the PROWG committee resolved not to follow the inspector’s recommendation, and instead decided to register the land as a town or village green. The committee was split 3-3, apparently on political party lines, and the resolution was passed only on the casting vote of the chair. It is clear from the decision of Sir Wyn Williams of 3 May 2018 (to which I am about to refer) that the decision was a highly contentious one, and that the members of the committee were subject to lobbying by interested persons.

31. I should add that, although the inspector recommended that the application be rejected on the grounds that the use of the land was not “as of right”, he rejected the argument based on statutory incompatibility. This was in line with the recent decision of the Court of Appeal in the Lancashire case, before that decision was reversed by the Supreme Court.

Judicial review

32. Before the committee’s decision was implemented, however, the claimant on 10 February 2017 sent a pre-action letter, and on 9 March 2017 commenced judicial review proceedings in relation to that decision. On 3 May 2018, Sir Wyn Williams, sitting as a judge of the High Court, quashed the decision: R (Cotham School) v Bristol City Council [2018] EWHC 1022 (Admin). His decision to do so was based on (i) an error of law by the authority in concluding that the use of the land by local inhabitants between 1991 and 2011 was “as of right”, and (ii) its failure “to provide adequate and sufficient reasons” for that conclusion.

33. In the course of his judgment the judge stated that Mr Mayer had “engaged in a campaign to persuade the [PROWG] committee that it should not accept the Inspector’s recommendation”. Moreover, he “sought to galvanise public support for the view that the land should be registered. At least one public meeting was held … ” However, the judge did not accept a further argument from the claimant, based on statutory incompatibility, in the light of the then recent decision of the Court of Appeal. On 25 June 2018, in accordance with the quashing decision of Sir Wyn Williams, the committee retook the decision, and this time resolved to reject the application by the casting vote of the chair (the committee again being split 3-3 on party lines).

Second and third applications for registration

The inspector’s third report

34. On 14 September 2018, a lady called Emma Burgess (who also gave evidence in this case) made a second application to register the land. On 22 July 2019, a third application so to register the land was made, by the second defendant, also a local resident. The reason for two separate applications is this. Ms Burgess’s application was made under section 15(2) of the 2006 Act, in respect of the 20 years immediately before that date. But that would involve consideration of the effect in law of the new notices erected in July 2018. The application could be amended, but, in order to sidestep the issue, the second defendant made a further application, this time under section 15(3) of the Act, in respect of the 20 years immediately before the erection of the new notices. As on previous occasions, the PROWG committee appointed Philip Petchey to report and make a recommendation.

35. First of all, Mr Petchey considered whether it was necessary to hold a public inquiry. In his report, dated 2 March 2021, he advised that a public inquiry was not needed. On the other hand, having considered the second and the third applications, his recommendation was to reject both of them. His report was given to the interested parties, and they commented on it. Indeed, Ms Burgess and the second defendant “adduced additional arguments and submitted additional material in support of them”. The claimant and the first defendant (both at that stage objectors to the applications) also made further representations. In the light of the further arguments and material, Mr Petchey reconsidered the matter, and produced a further report, dated 14 March 2023. He recommended that the applications be refused. Once again the report was provided to the interested parties who once again commented on it. Mr Petchey was asked to consider those comments, which he did. He produced a Note dated 18 May 2023, in which he adhered to his recommendation.

The decision to register

36. However, on 28 June 2023, the PROWG committee resolved, by six votes to one, to register the land as a town or village green on the second defendant’s application, despite Mr Petchey’s report. (No formal determination was made by the committee on Ms Burgess’s application.) Following that decision, a pre-action protocol letter was sent on behalf of the claimant on 20 July 2023, intimating a (fresh) claim for judicial review. A response was sent by the City Council on 3 August 2023. And then, on 22 August 2023, the land was so registered. Following that registration, the claimant commenced judicial review proceedings for a second time. However, on 11 September 2023, Eyre J stayed these proceedings until 1 March 2024. On 20 November 2023 the claimant issued the present claim under CPR Part 8, pursuant to section 14 of the Commons Registration Act 1965. On 25 April 2024, the judicial review claim was formally discontinued, leaving the present proceedings alone to be resolved.

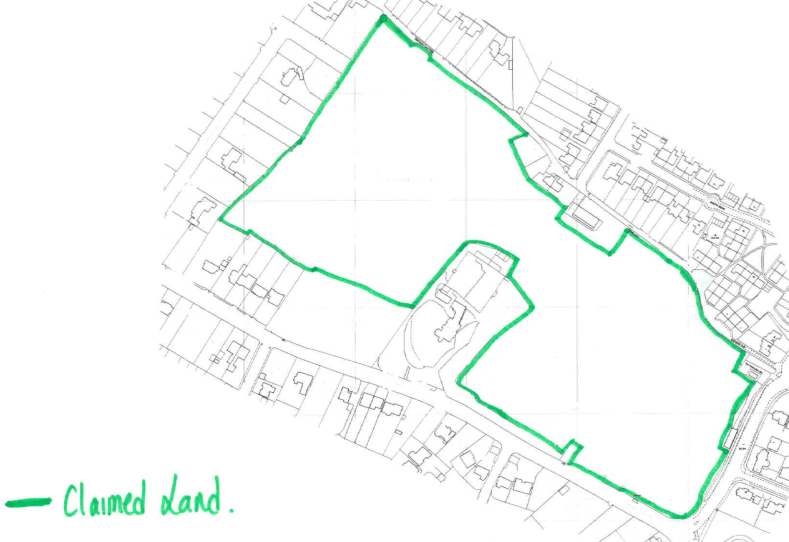

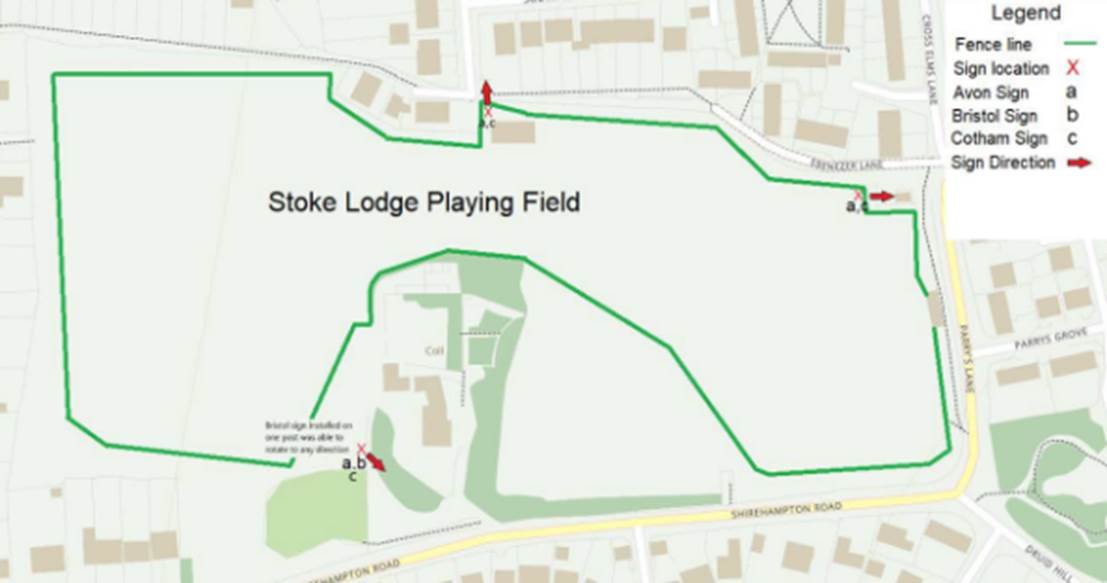

37. I set out below a plan of the area of land claimed by the second defendant to be, and accordingly later registered as, a town or village green. Once again, north is at the top of the plan. It will be seen that the area claimed, and then registered, does not include the area coloured blue on the plan of the demised land, but does include the Arboretum, which is not part of the demise, and in respect of which the City Council is the owner in fee simple absolute in possession. The City Council is the owner of the remainder of the land registered as a town or village green in fee simple absolute in reversion, that is, subject to the long lease granted to the claimant.

General

38. Having briefly sketched the history of the events leading to the present proceedings, it is desirable that I say something at this stage to introduce the applicable law and practice, though without going into too much detail. There are two main pieces of primary legislation which are relevant to this case, both of which I have already mentioned. They are the Commons Registration Act 1965 and the Commons Act 2006, each of which has been amended by subsequent legislation. The intention is that the regime of the latter should eventually replace that of the former. To this end, the 2006 Act prospectively repeals the whole of the 1965 Act. However, at present, that general repeal (and the new regime) applies to only a handful of so-called “pilot” or “pioneer” areas. Bristol is not one of them. But some elements of the new system do apply even in non-pilot areas. For example, the second defendant’s successful application to register the land was made under the 2006 Act and not the 1965 Act, though the entry was made in the register constituted under the 1965 Act. This makes the ascertainment of the relevant law much more difficult than it needs to be, especially when (as is obvious) this area of the law is of great interest to ordinary people who are not lawyers (much less, judges) but who have an interest in green open spaces in their locality, whether as owners or as would-be users. We are all better off for knowing where we stand.

39. This claim is actually brought under section 14 of the Commons Registration Act 1965. As originally enacted (but not yet repealed by the 2006 Act for land in Bristol), this provides that:

“The High Court may order a register maintained under this Act to be amended if—

(a) the registration under this Act of any land or rights of common has become final and the court is satisfied that any person was induced by fraud to withdraw an objection to the registration or to refrain from making such an objection; or

(b) the register has been amended in pursuance of section 13 of this Act and it appears to the court that no amendment or a different amendment ought to have been made and that the error cannot be corrected in pursuance of regulations made under this Act;

and, in either case, the court deems it just to rectify the register.”

This claim is not brought under section 14(a), and so only section 14(b) is relevant.

40. It will be noted that section 14(b) refers to “amendment in pursuance of section 13” of the 1965 Act. This latter section, as amended by the Law of Property Act 1969, provided that:

“Regulations under this Act shall provide for the amendment of the registers maintained under this Act where—

(a) any land registered under this Act ceases to be common land or a town or village green; or

(b) any land becomes common land or a town or village green; or

(c) any rights registered under this Act are apportioned, extinguished or released, or are varied or transferred in such circumstances as may be prescribed;

[ …]”

41. I say “provided”, because paragraph (a) of section 13 was repealed by the 2006 Act, as partially brought into force on 1 October 2006 by virtue of the Commons Act 2006 (Commencement No 1, Transitional Provisions and Savings) (England) Order 2006, SI 2006 No 2504. Yet article 3(3) of the order provides that

“(3) In relation to any area of England, section 13(a) of the 1965 Act and regulations made under it shall, until the coming into force of section 14 of the 2006 Act in relation to that area, continue to have effect insofar as they relate to land which ceases to be common land or a town or village green by virtue of any instrument made under or pursuant to an enactment.”

42. In like fashion, section 13(b) was repealed by the 2006 Act as partially brought into force on 20 February 2007 by virtue of the Commons Act 2006 (Commencement No 2, Transitional Provisions and Savings) (England) Order 2007, SI 2007 No 456. But article 4(1) of the order provided that

“(1) Where a commons registration authority grants an application under section 15 of the 2006 Act for the registration of land as a town or village green before section 1 of the 2006 Act has come into force in relation to the area in which the land is situated—

(a) it shall register the land in the register of town or village greens maintained for that area under the 1965 Act; and

(b) until the coming into force of section 1 of the 2006 Act in relation to that area, the 1965 Act shall apply in relation to the registration as if it had been made pursuant to section 13(b) of that Act.”

43. Neither section 1 nor section 14 of the 2006 Act has yet come into force in relation to land in Bristol. As I have already said, the second defendant’s successful application was however made under section 15 of the 2006 Act. That section relevantly provides:

“(1) Any person may apply to the commons registration authority to register land to which this Part applies as a town or village green in a case where subsection (2), (3) or (4) applies.

[ … ]

(3) This subsection applies where—

(a) a significant number of the inhabitants of any locality, or of any neighbourhood within a locality, indulged as of right in lawful sports and pastimes on the land for a period of at least 20 years;

(b) they ceased to do so before the time of the application but after the commencement of this section; and

(c) the application is made within [the relevant period].

[(3A) In subsection (3), ‘the relevant period’ means—

(a) in the case of an application relating to land in England, the period of one year beginning with the cessation mentioned in subsection (3)(b);

[ … ]

(8) The owner of any land may apply to the commons registration authority to register the land as a town or village green.

(9) An application under subsection (8) may only be made with the consent of any relevant leaseholder of, and the proprietor of any relevant charge over, the land.

(10) In subsection (9)—

‘relevant charge’ means—

(a) in relation to land which is registered in the register of title, a registered charge within the meaning of the Land Registration Act 2002 (c. 9);

(b) in relation to land which is not so registered—

(i) a charge registered under the Land Charges Act 1972 (c. 61); or

(ii) a legal mortgage, within the meaning of the Law of Property Act 1925 (c. 20), which is not registered under the Land Charges Act 1972;

‘relevant leaseholder’ means a leaseholder under a lease for a term of more than seven years from the date on which the lease was granted.”

44. In construing section 15, it is relevant to note two other provisions. The first is section 5, which explains the phrase “land to which this Part applies” in sub-s (1). Section 5 relevantly provides:

“(1) This Part applies to all land in England and Wales, subject as follows.

(2) This Part does not apply to—

(a) the New Forest; or

(b) Epping Forest.

(3) This Part shall not be taken to apply to the Forest of Dean.

[ … ]”

(The change in statutory language between sub-s (2) and sub-s (3) is mystifying, but there it is.)

45. The second is section 61(1) of the 2006 Act. This provides that, in the Act, “‘land’ includes land covered by water”, but there is no further elucidation of the concept of land as such. However, by section 61(3),

“In this Act -

(a) references to the ownership or the owner of any land are references to the ownership of a legal estate in fee simple in the land or to the person holding that estate;

(b) references to land registered in the register of title are references to land the fee simple of which is so registered.”

I shall return to these provisions in due course.

46. The application of the second defendant was made on 20 July 2019. It stated both (i) that it was made under section 15(3), and (ii) that the “relevant period” for the purposes of that provision ended on 23 July 2018. As will be seen, this was the date when the claimant erected certain signs on the land. It is thus clear that the second defendant’s application was based on local inhabitants’ indulging as of right in lawful sports and pastimes on the land between at least July 1998 and July 2018. As will also be seen, the phrase “as of right” is a legal term of art, featuring in a number of judicial decisions at the highest level. In effect, it requires a careful consideration of the precise circumstances in which the “indulging” took place. However, and as noted later, the parties have agreed that some (though not all) of the conditions set out in section 15(3) have been met in this case.

47. But there is a further point which must be investigated for the purposes of this claim. Unfortunately, however, this further point does not appear in the statutory text at all. Instead, it is recognised only in the caselaw (although, again, at the highest level). This is whether there would be any sufficient incompatibility between (i) the statutory purposes for which the land is held by the owner and (ii) the effect of its being designated as a town or village green under the 2006 Act. That in turn will require careful attention to the statutory provisions under which the land is held.

48. In the result, this claim concerning land in Bristol which has been registered as a town or village green pursuant to the second defendant’s application continues to be subject to section 13 of the 1965 Act in the form in which it is set out above, notwithstanding that the relevant provisions of the 2006 Act repealing section 13(a) and (b) have been brought into force. Moreover, the tests that have to be applied in law depend on the true effect of a number of important legal authorities. As I said in my decision last year, this kind of legal treasure hunt, searching in the interstices of secondary legislation for the text of the currently applicable law, and holding several inconsistent ideas in your mind simultaneously, is certainly not for the faint-hearted. In addition, the substantial caselaw, glossing the statutory text, especially in relation to the doctrine of statutory incompatibility, has to be taken into account. And, as to that, I had the benefit of a full day’s argument by three counsel, each expert in this somewhat arcane area of the law. “Ignorance of the law is no excuse”, as a proposition applying to the public at large, has a rather hollow ring in this context.

49. I will take the opportunity here to mention also section 16 of the Act, because it becomes relevant later on. This section enables the owner of land registered as a town or village green in certain circumstances to release the land from registration by offering equivalent land in exchange. It relevantly provides:

“(1) The owner of any land registered as common land or as a town or village green may apply to the appropriate national authority for the land (‘the release land’) to cease to be so registered.

(2) If the release land is more than 200 square metres in area, the application must include a proposal under subsection (3).

(3) A proposal under this subsection is a proposal that land specified in the application (‘replacement land’) be registered as common land or as a town or village green in place of the release land.

[ … ]

(9) An application under this section may only be made with the consent of any relevant leaseholder of, and the proprietor of any relevant charge over—

(a) the release land;

(b) any replacement land.

(10) In subsection (9) ‘relevant charge’ and ‘relevant leaseholder’ have the meanings given by section 15(10).”

50. I shall have to discuss the law in more detail later in this judgment, but in considering the facts of the case it will be helpful to bear in mind the following points. User of land as of right is user which is neither by force, nor in secret, nor by permission. In the traditional Latin phrase, it is “nec vi, nec clam, nec precario”. The use of the phrase “by force” (the ablative vi) in this expression is misleading. A better word might be “contentious”, in the sense that the owner objects to the user, even though not resorting to force to expel trespassers, or, indeed, resorting to it to prevent them entering. Depending on the circumstances, signs placed by the owner on the land (for example) may well indicate that the user is contentious, and thus is not user nec vi. The meaning of the words on any sign is a question of law for the court. In the present case the claimant says that the user of the land by local residents for “sports and pastimes” was contentious, both because of the use of signs and also because of other expressions of objection. The defendants, however, say that it was not. Lastly, user of land as of right must be uninterrupted during the whole 20-year period. If it is interrupted, the period starts again. The claimant says it was interrupted in the relevant period. The defendants say that it was not.

51. In order to satisfy the statutory requirements, the sports and pastimes indulged in by local residents over the 20-year period must be “lawful”. I shall come back to this question later.

52. The doctrine of statutory incompatibility in the context of the law of town and village greens does not appear expressly in the legislation. It was first enunciated by the Supreme Court in a case which it decided in 2015. It has since been further discussed in three further cases, two decided in the Supreme Court in 2019, and another in the same court in 2021. I shall have to refer to these cases in more detail later on in this judgment, but for present purposes I can say this. The cases hold that town and village green legislation does not apply to land where there is an incompatibility between (i) the statutory purposes for which the land is held and (ii) the use of that land as a town or village green. It will therefore be necessary for me to examine in some detail the purposes for which the land is held, and by whom. The claimant says that this doctrine applies in the present case. The defendants say that it does not.

53. I also need at this stage to refer shortly to a number of statutory provisions relating to education. Section 40 of the Local Government (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1982 dealt with nuisances committed on school premises. It relevantly provided that:

“(1) Any person who without lawful authority is present on premises to which this section applies and causes or permits nuisance or disturbance to the annoyance of persons who lawfully use those premises (whether or not any such persons are present at the time) shall be guilty of an offence and shall be liable on summary conviction to a fine not exceeding £50.

(2) This section applies to premises, including playgrounds, playing fields and other premises for outdoor recreation—

(a) of a school maintained by a local education authority … ”

(These provisions are now in substance contained in the Education Act 1996, section 547. It is not necessary to set them out.)

54. The Education Act 1996, section 10 (replacing section 1(1) of the Education Act 1944) imposed a general duty on the Secretary of State to promote education:

“The Secretary of State shall promote the education of the people of England and Wales.”

55. Further, by section 11(1),

“The Secretary of State shall exercise his powers in respect of those bodies in receipt of public funds which—

(a) carry responsibility for securing that the required provision for primary, secondary or further education is made—

(i) in schools ...

[ … ]

in or in any area of England or Wales, or

(b) conduct schools … in England and Wales,

for the purpose of promoting primary, secondary and further education in England and Wales.”

(By section 4(1) of the Act, “school” is defined to include “an educational institution which is outside the further education sector and the [wider] higher education sector and is an institution for providing—

[ … ]

(b) secondary education, or

[ … ]”.)

56. Section 14(1) of the 1996 Act (replacing section 8(1) of the Education Act 1944), imposes a general duty on local authorities to provide sufficient schools. It provides:

“A [ local authority] shall secure that sufficient schools for providing—

(a) primary education, and

(b) education that is secondary education by virtue of section 2(2)(a),

are available for their area.”

57. In addition, section 13(1) of the 1996 Act, as amended, provides that

“A [local authority] shall (so far as their powers enable them to do so) contribute towards the spiritual, moral, mental and physical development of the community by securing that efficient primary education, [and secondary education] [and, in the case of a [local authority] in England, further education,] are available to meet the needs of the population of their area.”

58. Turning to standards for schools, section 542 of that Act, as amended, relevantly provides:

“(1) Regulations shall prescribe the standards to which the premises of schools maintained by [ local authorities] … are to conform; and without prejudice to the generality of section 569(4) different standards may be prescribed for such descriptions of schools as are specified in the regulations.

(2) Where a school is maintained by a [ local authority] , the authority shall secure that the school premises conform to the prescribed standards.”

59. The relevant regulations are the School Premises (England) Regulations 2012 (SI 2012/1943), regulation 10(1) of which provides that

“Suitable outdoor space must be provided in order to enable—

(a) physical education to be provided to pupils in accordance with the school curriculum; and

(b) pupils to play outside.”

60. Next, there is safeguarding. Section 175 of the Education Act 2002, as amended, relevantly provides:

“(1) A [ local authority] shall make arrangements for ensuring that [ their education functions] are exercised with a view to safeguarding and promoting the welfare of children.

(2) The governing body of a maintained school shall make arrangements for ensuring that their functions relating to the conduct of the school are exercised with a view to safeguarding and promoting the welfare of children who are pupils at the school.”

61. That deals with local authority schools. Under the Academies Act 2010, section 1, the Secretary of State may enter into “Academy arrangements” with any person, under which the other person gives the undertakings (i) to establish and maintain an educational institution in England which meets the requirements of (amongst other things) academy schools, and (ii) to carry on, or provide for the carrying on, of the institution.

62. Because section 542 of the 1996 Act does not apply to academies, there are equivalent regulations made under section 94 of the Education and Skills Act 2008, namely, the Education (Independent School Standards) Regulations 2010 (as amended in 2014), regulation 3 and paragraph 7 of schedule 1 of which provide that:

“The standard in this paragraph is met if the proprietor ensures that—

(a) arrangements are made to safeguard and promote the welfare of pupils at the school; and

(b) such arrangements have regard to any guidance issued by the Secretary of State.”

The claimant is inspected under section 108(1) of the 2008 Act for compliance with the standards, and there are consequences for failure to comply, ultimately involving potential criminal liability.

63. Finally in this section of my judgment, for completeness I set out here certain provisions of the Local Government Act 1972 dealing with the powers of local authorities to acquire, appropriate and dispose of land. These provisions are relevant in considering what the local authorities have done. They relevantly provide:

“120. (1) For the purposes of—

(a) any of their functions under this or any other enactment, or

(b) the benefit, improvement or development of their area,

a principal council may acquire by agreement any land, whether situated inside or outside their area.

(2) A principal council may acquire by agreement any land for any purpose for which they are authorised by this or any other enactment to acquire land, notwithstanding that the land is not immediately required for that purpose; and, until it is required for the purpose for which it was acquired, any land acquired under this subsection may be used for the purpose of any of the council's functions.

(3) Where under this section a council are authorised to acquire land by agreement, the provisions of Part I of the Compulsory Purchase Act 1965 (so far as applicable) other than section 31 shall apply, and in the said Part I as so applied the word “land” shall have the meaning assigned to it by this Act

[ … ]

122. (1) Subject to the following provisions of this section, a principal council may appropriate for any purpose for which the council are authorised by this or any other enactment to acquire land by agreement any land which belongs to the council and is no longer required for the purpose for which it is held immediately before the appropriation; but the appropriation of land by a council by virtue of this subsection shall be subject to the rights of other persons in, over or in respect of the land concerned.

[ … ]

123. (1) Subject to the following provisions of this section, [and to those of the Playing Fields (Community Involvement in Disposal Decisions) (Wales) Measure 2010,] a principal council may dispose of land held by them in any manner they wish.

(2) Except with the consent of the Secretary of State, a council shall not dispose of land under this section, otherwise than by way of a short tenancy, for a consideration less than the best that can reasonably be obtained.

[ … ]

270. (1) In this Act, except where the context otherwise requires, the following expressions have the following meanings respectively, that is to say—

[ … ]

‘land’ includes any interest in land and any easement or right in, to or over land;

[ … ]”

What this case is about

64. This claim is brought under section 14 of the 1965 Act, set out above. What the court must do is to decide whether, at the point of registration, the land the subject of the claim met the statutory criteria for a town or village green. If the court decides that it did, then that is the end of the claim. However, if the court decides that it did not, then it must go on to consider whether it deems it “just” to rectify the register. If the court deems it just to do so, then the court “may order” that rectification. It appears from the language used that, in those circumstances, the court enjoys a measure of discretion as to whether to order rectification. Given that the court must consider that it is “just” to rectify the register before it can arrive at that position, it is not easy to see what any further discretion adds to the position. One might have thought that, if it were just to rectify the register, any exercise of discretion not to do so would be regarded as irrational.

65. The claimant puts forward six grounds upon which it says it is entitled to succeed in its claim. I shall have to discuss these in more detail later in this judgment, but for present purposes I can summarise them as follows.

66. The first ground is that registration was precluded by the doctrine of statutory incompatibility. The claimant says that this arises in three ways, namely (i) in relation to the purpose for which the first defendant holds the freehold reversionary interest in the land, (ii) in relation to the purpose for which the Secretary of State for Education uses the land, and (iii) in relation to the purpose for which the claimant holds the leasehold interest in the land.

67. The second ground is that the signs which were erected on the land was sufficient to render use of the land by the public “contentious”, and thus not “as of right”.

68. The third ground is that the claimant’s objection to the first application (in 2011) also operated to render use of the land by the public “contentious”.

69. The fourth ground is that the terms of the lease rendered use of the land by the public by permission, so that it could not be “as of right”.

70. The fifth ground is that use of the land by the public was not continuous over the whole land throughout the 20-year period. It is said that the land was so extensively used for cricket, football and athletics as to interrupt use by the public.

71. The sixth ground is that the inhabitants’ use was not lawful, as contrary to various provisions of education legislation.

72. It goes almost without saying that the defendants deny that any of these grounds justifies the court in making the order sought by the claimant.

73. For the benefit of the lay parties concerned in this case I will say something about how English judges decide civil cases like this one. I borrow the following words largely from other judgments of mine in which I have made similar comments. The point is that there are a number of important procedural rules which govern the decision-making of judges, and which are not as well-known as they might be. I shall briefly mention some of them here, because non-lawyer readers of this judgment may not be aware of them.

74. The first is the question of the burden of proof. Where there is an issue in dispute between the parties in a civil case (like this one), one party or the other will bear the burden of proving it. In general, the person who asserts something bears the burden of proving it. Here the claimant bears the burden of proving its case, ie (i) that the land did not satisfy the legislative test for a town green and (ii) (if so) that it is just to amend the register accordingly. The importance of the burden of proof is that, if the person who bears that burden satisfies the court, after considering the material that has been placed before the court, that something happened, then, for the purposes of deciding the case, it did happen. But if that person does not so satisfy the court, then for those purposes it did not happen. The decision is binary. Either something happened, or it did not, and there is no room for maybe. That may mean that, in some cases, the result depends on who has the burden of proof.

75. Secondly, the standard of proof in a civil case is very different from that in a criminal case. In a civil case like this, it is merely the balance of probabilities. This means that, if the judge considers that something in issue in the case is more likely to have happened than not, then for the purposes of the decision it did happen. If on the other hand the judge does not consider that that thing is more likely than not to have happened, then for the purposes of the decision it did not happen. It is not necessary for the court to go further than this. There is certainly no need for any scientific certainty, such as (say) medical or scientific experts might be used to.

76. Thirdly, in our system, judges are not investigators. They do not go looking for evidence. Instead, they decide cases on the basis of the material and arguments put before them by the parties. They are umpires, or referees, AND not detectives. So, it is the responsibility of each party to find and put before the court the evidence and other material which each wishes to adduce, and formulate their legal arguments, in order to convince the judge to find in that party’s favour. There are a few limited exceptions to this, but I need not deal with those here.

77. Fourthly, more is understood today than previously about the fallibility of memory. People misremember. They make mistakes. In commercial cases, at least, where there are many documents available, and witnesses give evidence as to what happened based on their memories, which may be faulty, civil judges nowadays often prefer to rely on the documents in the case, as being more objective: see Gestmin SGPS SPA v Credit Suisse (UK) Ltd [2013] EWHC 3560 (Comm), [22], restated recently in Kinled Investments Ltd v Zopa Group Ltd [2022] EWHC 1194 (Comm), [131]-[134]. As the judge said in that case,

“a trial judge should test a witness's assertions against the contemporaneous documents and probabilities and, when weighing all the evidence, should give real weight to those documents and probabilities”.

In the present case, there are a large number of useful documents available. This is important in particular where, as here, the relevant facts have occurred over many years.

78. In deciding the facts of this case, I have therefore had regard to the more objective contents of the documents in the case. In addition to this, and as usual, in the present case I have heard witnesses (who made witness statements in advance) give oral evidence while they were subject to questioning. This process enables the court to reach a decision on questions such as who is telling the truth, who is trying to tell the truth but is mistaken, and (in an appropriate case) who is deliberately not telling the truth. (Different considerations apply to the witnesses who gave evidence before the inspector, as I discuss below.) I will therefore give appropriate weight to both the documentary evidence and the witness evidence, both oral and written, bearing in mind both the fallibility of memory and the relative objectivity of the documentary evidence available.

79. Fifthly, a court must give reasons for its decisions. That is the point of this judgment. But judges are not obliged to deal in their judgments with every single point that is argued, or every piece of evidence tendered. Judges deal with the points which matter most. Put shortly, judgments do not explain all aspects of a judge’s reasoning, and are always capable of being better expressed. But they should at least express the main points, and enable the parties to see how and why the judge reached the decision given.

Live witnesses

80. In the present case I heard from the following witnesses of fact on behalf of the claimant: Alison Crosland (Director of Finance and Resources at the claimant school), Joanne Butler (Headteacher of the claimant school), and Nathan Allen (former IT Manager and later Facilities Manager at the claimant school). I heard from the following witnesses of fact on behalf of the second defendant: the second defendant herself (local resident), John Goulandris (local councillor), Susan Mayer (wife of the applicant in the first application in 2011), Emma Burgess (applicant in the second application) and Helen Powell (local resident). As I have said, the first defendant called no witnesses of fact. It did however supply some copies of local user forms (created for the purposes of the second application) which had not found their way into the trial bundle.

81. I carefully observed all of the witnesses called whilst they were being cross-examined. I may say at once that, in my judgment, all of them were attempting to assist rather than to mislead the court. They told me what they believed to be true. I therefore reject any suggestion that any witness was deliberately telling lies. Nevertheless, I think that some memories were better than others, and on a few occasions I thought that one or two witnesses had convinced themselves that what they mistakenly believed to have happened had actually happened. This is a common phenomenon, and is frankly is not unexpected in any case where the witness has had a long time to think about what happened about events that happened many years ago. False memories can easily take the place of genuine ones, and be as convincing as any to the witness. Part of my function is to bring a measure of objectivity to the evaluation of the evidence.

82. At the outset of the trial, I raised the question of the admissibility in evidence of the material contained in the inspector’s various reports (including his own opinions as to findings of fact). It was submitted to me that the contents of the reports were admissible, not least having regard to certain observations of Lightman J at first instance in Betterment Properties (Weymouth) Ltd v Dorset County Council [2007] 2 All ER 1000, [15], [20]. That was a case like the present, in which the owner of land which had been registered as a town or village green applied under section 14 of the 1965 Act for an order removing the land from the register. Two preliminary issues were ordered to be tried. One was “Whether the jurisdiction conferred by section 14(b) of the Commons Registration Act 1965 is by way of rehearing or appellate or on some other basis?”

83. The judge summarised the parties’ submissions on this issue as follows:

84. It will be seen that the issue did not concern the rules of evidence as such. Instead, it concerned the question whether the court was in principle confined to the evidence before the registration authority (as the authority said), or whether the parties were free to adduce whatever evidence they wished, whether it had been before the authority or not (as the applicant said). No attention was paid to, and no cases were cited on, the question of admissibility of certain kinds of evidence in the proceedings.

85. The judge considered the statutory language used, and said:

86. Then follow the observations relied on in the present case:

[ … ]

20. I accordingly hold in answer to the first question that Section 14 imposes no fetter on the evidence or arguments which may be relied on to establish that no amendment or a different amendment should have been made, even as it imposes no fetter on the evidence or argument which may be relied on to establish that it is or is not just to rectify the register; and that it is a matter for the judge hearing the application under Section 14 in the exercise of his case management powers to decide the procedure to be adopted and what should stand as evidence and what should be admitted as evidence at the trial.”

87. It is thus apparent that the judge was directing his attention to the kind of proceeding that was to be conducted. It was not to be an appeal, or a review, but a proceeding de novo, in which evidence was to be at large. I cannot regard the judge’s observations set out above as dealing with the rules as to admissibility of whatever evidence the parties wished to adduce. That was simply not before him. It did not arise as part of the issue as to whether it was an appeal or a new proceeding, and none of the relevant authorities was referred to. The decision of Lightman J was taken to the Court of Appeal, which affirmed his decision on both preliminary points: [2009] 1 WLR 334. Lloyd LJ (with whom Laws and Rix LJJ agreed) cited paragraph 15 of Lightman J’s judgment, and expressly stated (at [28]) that he agreed with it. Once more, however, there was no discussion of the rules of the admissibility of evidence, or any citation of authority relating to that.

88. I further note that the observations of Lightman J were subsequently cited with apparent approval by Patten LJ in the Court of Appeal in its later decision in Taylor v Betterment Properties (Weymouth) Ltd [2012] 2 P & CR 3, [18]. This was an appeal from the decision of Morgan J, who had heard the substantive application in the same case under section 14. That judge held ([2010] EWHC 3045 (Ch)) that the land should not have been registered, and that it was just to rectify the register to remove it. A local resident sought to appeal that decision. But the observations of Patten LJ were preceded by these introductory words:

“18. The hearing of the preliminary issues took place before Lightman J in March 2007: see [2007] EWHC 365 (Ch). He held that the jurisdiction exercised by the court on a s.14(b) application was not merely appellate or supervisory.”

Once again, therefore, the court was simply not concerned with admissibility of evidence, but with the very nature of the proceeding. No authorities on admissibility were cited.

89. In these circumstances I consider that the matter is res integra, and that I must deal with the matter of admissibility myself. Hearsay evidence was formerly inadmissible in civil proceedings. It was not on oath, the demeanour of the witness could not be observed, and there could be no cross-examination, with the result that the evidence could not be tested. Such evidence was first rendered admissible in civil proceedings by the Civil Evidence Act 1968, section 1 and 2, now replaced by the Civil Evidence Act 1995, sections 1 and 2. Accordingly, the court is well able to admit in evidence in these proceedings the evidence that was received by the inspector in holding his non-statutory inquiries, even though it is conveyed through the medium of his reports. Indeed, the oral evidence recorded by the inspector differs from most oral hearsay evidence, because it was in fact subject to cross-examination before the inspector. So it was tested.

90. However, what does concern me is how it is possible for the court to admit or even accept the findings of fact which the inspector made after receiving that evidence. The inspector is not thereby giving evidence of what he himself heard or saw. Instead, basing himself upon what he heard or saw, he is giving his opinion as to what happened. In the general law of evidence, such opinions as to matters of fact in issue in this case are inadmissible as opinion evidence going to issues before the court. This often referred to as the rule in Hollington v Hewthorn [1943] KB 857, where the conviction of a driver for careless driving was held by the Court of Appeal to be inadmissible in evidence in a claim against the driver for negligence. Thus, in Land Securities plc v Westminster City Council [1993] 1 WLR 286, Hoffmann J held that the findings of an arbitrator in an earlier arbitration were not even admissible evidence in a subsequent proceeding.

91. In Rogers v Hoyle [2015] 1 QB 265, the Court of Appeal pointed out that, although the rule has in fact been abrogated in relation to criminal convictions, it still

“34. … applies to the findings of facts of arbitrators … of coroners or coroners' juries … of persons conducting a Wreck Inquiry … and to the findings of individuals, of however great distinction, conducting extra statutory inquiries such as Lord Bingham's Report into the Supervision of BCCI … ”

92. The Court concluded that

“39. The foundation on which the rule [in Hollington v Hewthorn] must now rest is that findings of fact made by another decision maker are not to be admitted in a subsequent trial because the decision at that trial is to be made by the judge appointed to hear it (‘the trial judge’), and not another. The trial judge must decide the case for himself on the evidence that he receives, and in the light of the submissions on that evidence made to him. To admit evidence of the findings of fact of another person, however distinguished, and however thorough and competent his examination of the issues may have been, risks the decision being made, at least in part, on evidence other than that which the trial judge has heard and in reliance on the opinion of someone who is neither the relevant decision maker nor an expert in any relevant discipline, of which decision making is not one. The opinion of someone who is not the trial judge is, therefore, as a matter of law, irrelevant and not one to which he ought to have regard.”

93. Of course, it is possible for Parliament to make legislative provision inconsistent with the rule in Hollington v Hewthorn, just as it did in relation to criminal convictions. But I do not think that Lightman J in the Betterment case thought that it had also done so in the town and village green legislation. He did not advert to the rule, or to any specific provisions of the legislation, and neither did he explain any reasoning by which he might have considered that the terms of that legislation had partially abrogated the rule for its own purposes. Nor did the Court of Appeal on appeal from him, or indeed in the later Betterment case. For myself, I see nothing in the terms of the legislation even to suggest, much less to require, that the rule in Hollington v Hewthorn should not apply to the findings of fact of the registration authority or some person acting on its behalf. Indeed, the statute is completely silent on questions of evidence. I see no scope for inferring that the legislation has effected such an important change to the rules of evidence in applications under section 14.