Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

England and Wales High Court (Chancery Division) Decisions

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> England and Wales High Court (Chancery Division) Decisions >> Miles & Anor v Reid & Anor [2025] EWHC 1347 (Ch) (06 June 2025)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Ch/2025/1347.html

Cite as: [2025] EWHC 1347 (Ch)

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

CHANCERY DIVISION

BUSINESS AND PROPERTY COURTS OF ENGLAND AND WALES

Fetter Lane, London, EC4A 1NL |

||

B e f o r e :

____________________

| (1) Dominic Miles (2) Helen Faber |

Appellants |

|

| - and - |

||

| (1) Richard Reid (2) Katheryn Reid |

Respondents |

____________________

Anya Newman (instructed by Browne Jacobson LLP) for the Respondents

Hearing date: 30 April 2025

____________________

Crown Copyright ©

- This judgment concerns a dispiriting dispute about a boundary and right of way between two neighbouring properties in Banbury, Oxfordshire, the Appellants' property known as Peartree Cottage (PTC), the Respondents' property known as Forge Cottage (FC).

- Until 1944, PTC and FC were in single ownership. However, by a conveyance dated 1 June 1944 (1944 Conveyance), FC was conveyed into separate ownership, the property described therein in the following terms:-

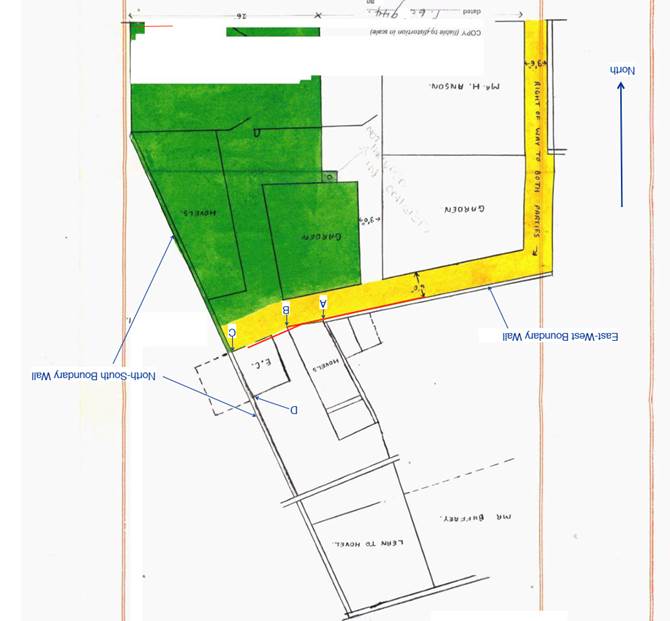

- The map or plan attached to the 1944 Conveyance (1944 Plan) (annotated by the Appellant for the hearing before me (reproduced from appeal bundle at [p.6])), rotated 180 degrees to show a north facing orientation, is below:-

- The 1944 Conveyance granted the following right of way (Right of Way):-

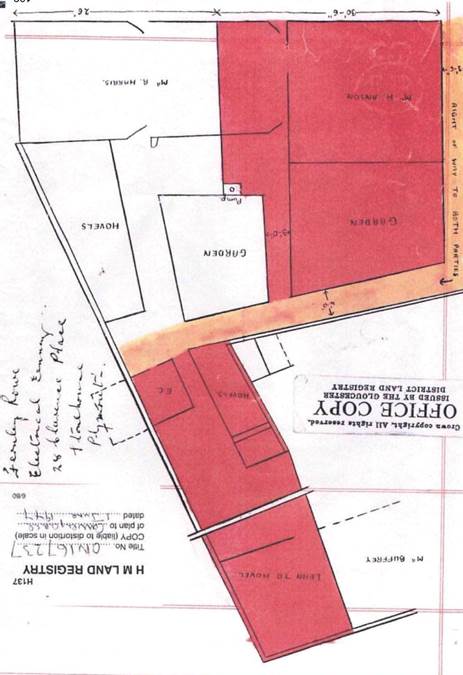

- There is no dispute that the adjoining premises referred to is PTC, the registered title to which records a conveyance also dated 1 June 1944 conferring on PTC the benefit of the Right of Way. The plan attached to that further conveyance (below, also rotated (reproduced from appeal bundle at [p.7])) shows that PTC is made up of two parcels, comprising (i) to the north, the cottage and garden adjoining FC and (ii) to the south, what has been described as PTC's second or southern garden to which access is only available by means of the Right of Way. The land conveyed is coloured red on the plan, the Right of Way pinky brown (stated as yellow in the conveyance).

- The dispute between the parties arose after the Respondents replaced an existing fence between the two properties. The Appellants claimed that the new fence obstructed the Right of Way and that it encroached on PTC land and prevented access to a brick outbuilding which they said stood on both properties and was, in part, owned by them. In addition, the Appellants contended that the Respondents had deliberately sought to obstruct the sale of PTC. However, the Appellants did not pursue their original request for an access order under the Access to Neighbouring Land Act 1992, having discontinued this aspect of the claim in January 2023.

- The Respondents denied that any part of the new fence encroached on PTC land. They also denied obstruction of the Right of Way, albeit accepting at trial that a small part did encroach on the Right of Way where it met the existing brick outbuilding. They also denied that any part of that outbuilding belonged to the Appellants or that they had any right of access to it. Finally, they denied any obstruction of the Appellants' attempts to sell PTC. They also counterclaimed in trespass for the installation without consent of an oil line and a patio area over the Right of Way, seeking injunctive relief against the Appellants to restrain those alleged trespasses but not pursuing the related claim in damages.

- In closing submissions below, the Appellants accepted that the oil line was a trespass but argued that the Court should not require them to remove it, albeit their defence of necessity was not pursued with conviction. The judge did not permit them to argue estoppel by acquiescence, that argument having only been raised in closing submissions after the Respondents had closed their case at trial.

- In her reserved judgment, the judge found in favour of the Respondents on the position of the boundary between the properties and the extent of the Right of Way. She also found that the new fence was on the line of the previous fence save that, by the outbuilding, the 'dogleg' now introduced did encroach 40cm onto the Right of Way, albeit not such as to represent a substantial interference. The judge therefore declined an injunction to move the fence. She also found that the outbuilding was on FC land and owned by the Respondents. She dismissed the claim in relation to the sale of PTC. Finally, she found that the installation of both the oil line and the patio area constituted trespasses to FC's land and granted related injunctive relief. In essence, she dismissed the Appellants' claim and upheld the Respondents' counterclaim.

- I heard the Appellants' application for permission to appeal at a rolled up hearing on 30 April 2025. I now address the grounds of appeal (Grounds) in the order in which they were argued at the appeal hearing.

- The question of the position of the boundary between FC and PTC's southern garden was encompassed by Grounds 3, 4 and 5, as summarised below:-

- I consider these three Grounds compositely as the Appellants did at the hearing. The Appellants say that there was no issue that, as the judge found, the 1944 Plan was the primary document establishing the position of the boundary. However, the judge interpreted this wrongly. In the absence of any claim of a change in boundary by agreement or adverse possession (not present in this case), the question for the judge to decide was where the parties to the 1944 Conveyance intended the boundary to be. That was a question of construction and of law, for which purpose, the evidence of surveyors was inadmissible (see Phipson on Evidence 20th ed. at [33.106]-[33.107]). Phipson cites to that end LHS Holdings Ltd v Laporte Plc [2001] 2 All ER (Comm) 563 CA which held (at [36]) that expert accountancy evidence was not required to construe a disputes notice served under a share sale and purchase agreement. Whether the notice provided "reasonable details for the grounds of dispute" was the very question which the court had to decide. In the specific context of a conveyance of land, Grigsby v Melville [1974] 1 WLR 80 held (at [86A-E]) that evidence as to layout and history of the relevant properties was not admissible to show that the cellar was excluded from the conveyance when, on its clear terms, it was included. As Stamp LJ found, the conveyance was not, for example, one in which an inspection of the ground would show that the boundary of the property had been inaccurately described.

- The Appellants therefore argued that, unless the conveyance was ambiguous or there was some uncertainty, extrinsic evidence was not admissible. Even where it might be admissible, the relevant question is whether it assists the court to determine what the parties to the 1944 Conveyance intended. In Neilson v Poole 20 P&CR 909, for example, Megarry J held (at [32]-[34]) that evidence of what the common vendor had done in subsequent conveyances was admissible to assist in construing a parcels clause in a conveyance and the ascertainment of a boundary. In Clarke v O'Keefe [2000] 80 P&CR 126, it was common ground that, if a transfer clearly defined the land transferred, extrinsic evidence would not be admissible to contradict the transfer. However, in that case, the only meaningful description of the land in the parcels clause was by reference to the plan but the red edging of the relevant boundary was a broad line on a plan which used a blown up small scale ordnance survey map, marked along the vegetation line as it was some years before the transfer. Citing Neilson (at [133]), Peter Gibson LJ noted the undiminished modern tendency to admit evidence in boundary disputes and to assess its weight rather than exclude it, going on to find in that case that it would be somewhat absurd for the court to shut its eyes to evidence of what the parties had agreed in light of the lack of clarity as to the true position of the boundary.

- Turning to this case, the Appellants accept that there was a small ambiguity as between the two conveyances executed on 1 June 1944 and that it would be appropriate to admit them both, but submit that the evidence of the surveyors some 80 years after the event was not required or permissible. Indeed, the 1944 Conveyance describes the land conveyed, not by way of identification, rather than as "more particularly described in the map or plan drawn hereon and thereon coloured green and yellow". The 1944 Plan was therefore intended to define the boundary between FC and the PTC southern garden, there is no ambiguity or lack of clarity in that regard and this is nothing like the boundary shown on the plan ordered by the judge. Looking at the above annotated version, the 1944 Plan clearly shows that:-

- As to the admitted ambiguity between the two conveyance plans from 1944, namely the different boundary line angles from the point it meets the hovels in the PTC southern garden, the Appellants submitted that it was more likely than not that the parties intended in 1944 for there to be a continuation of the line of the east-west boundary wall at that point in the manner shown on the conveyance plan for PTC, there being no need to introduce a deviation at that point.

- The Appellants also say that the judge's finding that the disputed Right of Way narrowed from point 'A' was perverse. The use of a ruler on a printed copy of the 1944 Conveyance proves that the yellow land was not drawn as if it narrowed or that any narrowing was de minimis. Any illusion otherwise was probably caused by the fact that the yellow land is wider at point 'C'. However, the two sides of the line of the Right of Way remain in parallel.

- There being no (or no material) ambiguity in the 1944 Conveyance or the 1944 Plan, and there being no claims by either party that the line of the disputed boundary had changed, the position of the disputed boundary is capable of determination with adequate precision without the need to consider any expert evidence or any other document. The 1944 Plan is equally illuminating for what it does not show; it does not show the boundary turning 90 degrees into the area of the hovels in the PTC south garden. No reasonable judge properly construing the 1944 Plan could have formed the view that the 1944 Conveyance created a right of way as shown on the plan ordered by the judge in this case.

- Finally, even if extrinsic evidence were admissible, the plan from 1994 shows that HMLR interpreted the boundary consistent with its continuation along the line of the east-west boundary line as contended for by the Appellants.

- The judge therefore erred in treating this case as a 'beauty contest', preferring one surveyor expert over the other, the plan she ordered coming about from the adoption of the opinion of the Respondents' surveyor that the boundary of FC with the southern garden was at the position of the high stone wall on the northern-southern boundary. In that regard, the Appellants suggested that Ms Ellis-Greenway's report (at [4.3.5]) indicated erroneously that the high stone wall ran behind the Earth Closet. Moreover, the factual evidence of Mr Brakespear relied on by the judge in reaching her findings about the location of point 'C' did not differentiate between the north and south ends of the Earth Closet.

- On any view, even if there were an ambiguity, no reasonable judge could have found the boundary line on the basis of the plan as ordered. Such a finding was perverse. Requiring a significant change to the title plan, it would also undermine the certainty inherent in the system of registration of land.

- Having considered the Appellants' arguments on the position of the boundary, I found none persuasive:-

- As to the nature and analysis of that evidence, the judge first satisfied herself that it was appropriate to identify the boundary line by reference to physical features shown on the 1944 Plan; she identified the location of the Earth Closet in PTC's south garden as significant for that purpose; she considered Mr Mycock's change of position as to whether the northern end of the Earth Closet had been immediately next to the end of the high stone wall along the north-south boundary; and she considered the factual evidence, including that of Mr Brakespear, as to the presence and location of the Earth Closet on his neighbouring land which mirrored the location of the corresponding structure formerly in PTC's south garden.

- Such evidence as to the location of former structures on the 1944 Plan was directed to the intention of the parties at the time of the execution of the 1944 Conveyance. Although the expert surveyors came to their own different conclusions as to the location of the boundary line, the judge did not simply adopt the Respondents' expert evidence. She carefully considered the related expert, factual, documentary and photographic evidence and came to the conclusion that the end of the western boundary line (point 'C') was marked by the end of the high stone wall.

- I did not discern the ambiguities suggested by the Appellants at the appeal hearing in the evidence of the Respondents' relevant witnesses. These were in any event matters for the judge's assessment and it is clear from her analysis of the evidence and findings that they did not give rise to any misapprehension on her part.

- In conclusion, the judge's approach was an entirely appropriate one. She was entitled on the evidence to come to the view she did about the position of the boundary. Given the inaccuracies in the 1944 Plan, the visual differences with the plan as ordered cannot be said to render her decision perverse nor otherwise outside the range of findings reasonably available to her on the evidence.

- Grounds 3-5 disclose no real prospect of success.

- The Right of Way issue concerns the position of the new fence erected by the Respondents in 2021. The Appellants asserted below that this did not follow the line of the original fence and encroached onto the Appellants' land. The judge did not accept this but did accept the evidence of the fence erector, Mr Steel, who testified that the fence followed the original line save for the point at which the new fence was squared off next to the Respondents' outbuilding. She also accepted the joint opinion of the expert surveyors that the new fence encroached by some 40cm onto the Right of Way at that point. She did not accept, however, that such encroachment represented a substantial interference with the Right of Way.

- The question of whether there was any substantial interference with the Right of Way and, in this context, the nature of the grant, was encompassed by Grounds 1 and 2, as summarised below:-

- As to Ground 1, the judge set out at (at [60]-[63]) the law regarding what constitutes a substantial interference with a right of way:-

- In relation to (i), this comes from a statement of Russell LJ (with whom Davies LJ and Sellers LJ agreed) in Keefe v Amor [1965] 1 Q.B. 334 at paras C-D on page 347 who said (with express reference to private rights of way):

- Although obiter in Keefe v Amor, this was approved and followed by the Court of Appeal in, inter alia, Celsteel (and from thence into Briggs J's principles in Zielenewski) and Taylor v Burton & Burton [2014] EWCA Civ 21.

- Accordingly, the burden of proof is on the Claimants to prove to the civil standard that the obstruction of the right of way as to 400mm by the New Fence at the outbuilding substantially interferes with their exercise of their right of way "as for the time being is reasonably required" by them."

- The Appellants accepted before me that the judge had correctly stated the law at paragraph 60. Although they did dispute in their appeal skeleton the proposition (at [63]) that the burden lay on them to prove that the obstruction was actionable, they did not press this point in oral submission. In my view, they were right not to do so, it being clear from the authorities (as supported by Gale on Easements (at [13-03])) that it was for the party claiming substantial interference to make good that claim. The Appellants did not seek to challenge under these Grounds the factual findings of the judge (save for her acceptance of one aspect of Mr Steel's evidence discussed below). Rather, they say that, if the judge had properly applied the law to those facts, in particular, the three points at paragraph 60(iii)-(v) of her judgment (above), she would have concluded that the interference was obviously actionable as a substantial interference.

- At trial, the nature of the interference was said to be reflected in the Right of Way now being inadequate to push a wheelbarrow, bicycle or wheelchair. Although the judge did not accept that the right to pass and repass on foot encompassed a right to push wheeled vehicles along its length, she went on to find (at [69]) on the basis of Mr Steel's evidence that, even if she were wrong about that, a wheelchair user could substantially and practically use the Right of Way as conveniently as before, the only difference being a minimal one of negotiation of a dogleg rather than a kink. She did not consider reasonable the Appellants' insistence on the use of the whole of the Right of Way to avoid a minimal additional manoeuvre by a notional wheelchair user who might one day wish to access the PTC southern garden. Negotiating that dogleg on foot was also immaterial to the use of the Right of Way which remained substantially and practically convenient as before. Finally, as for the Appellants saying that they had found the Right of Way less convenient when they were emptying their belongings from an outbuilding, the judge was satisfied on the evidence that the Right of Way can never have been intended to be used by occupants of PTC to gain access to the outbuilding concerned such that no issue of interference arose.

- The Appellants made clear that they were not asserting on this appeal that the Right of Way could no longer be used. Rather, they said that it could not be used as conveniently as before, contrasting this case with West v Sharp concerning the grant of a right of way over a 40 foot strip. Some years earlier, and without objection, this had been narrowed to 13 feet, with concrete blocks and trees also placed along both sides. However, this still left the ability for two vehicles to pass one another without difficulty. The Court of Appeal concluded that the judge's declination of injunctive relief was a matter of fact and degree justified by the evidence. In this case, however, the Appellants said that, even a small reduction in width of the 4 foot Right of Way, let alone to 2ft 8in with the introduction of a dogleg, would mean that it could not practically be used as conveniently as before, with much greater care now required. The Appellants raised the further suggested difficulty of using the Right of Way when carrying a metre wide chattel such as a picnic tray with full glasses, positing, for example, that a 3ft 11in wide tray could just get through without spilling the drinks, a 3ft 6in tray with greater ease given the play on either side. Since it was not unreasonable for the Appellants to insist on being able to use the way conveniently and without having to take such great care, the judge ought to have found that the encroachment of the fence was a substantial interference.

- The Appellants' arguments directed to Ground 1 were, likewise, unpersuasive. First, they were premised on the proposition that the Right of Way at the point of encroachment was originally 4 feet wide but, as the judge found (and was entitled to find based on the evidence), the Right of Way was not uniform along its path.

- Second, there was, unsurprisingly, no challenge on the appeal to the judge's findings with respect to those suggested difficulties which the Appellants had identified, namely the lesser convenience in the removal of items from the outbuilding.

- Third, the Appellants did challenge the judge's findings as to the lack of substantial interference in terms of wheelchair access. The difficulty with this was that Mr Steel had testified that, even with the squaring off of the fence at the point of the FC outbuilding, the Right of Way could still be used as conveniently as before, including by a wheelchair. The Appellants challenged this factual finding on the basis it was opinion evidence by Mr Steel. However, this submission was problematical: (a) it was the Appellants who had asked Mr Steel for his view in cross-examination (b) Mr Steel had erected the fence, he was well aware of the Right of Way and he was therefore able to give meaningful evidence as to the convenience of its use thereafter and (c) as the Respondents noted before me, there did not appear to be any positive evidence from the Appellants as to the requirement for, or convenience of, such use rather than, assertion on the latter point at least. Having correctly identified the legal principles engaged, the judge was therefore entitled to reach the conclusions she did that the interference was minimal and not substantial. The same holds good for the pushing of other wheeled chattels such as a lawnmower or bicycle.

- Finally, the Appellants' point about carrying a metre wide tray with filled glasses did not advance matters on the appeal. Even if there had been any evidence before the judge about the reasonable requirement for, and relative convenience of, this mode of use before and after the installation of the new fence, anyone using the Right of Way for that purpose would always have to exercise great care in navigating an already narrow path (with or without the new dogleg at the end).

- Ground 1 discloses no real prospect of success. As such, it is not necessary for me to consider Ground 2, which falls away.

- In summary, the Appellants maintained under Ground 6 that the judge was wrong in law to grant an injunction requiring the Appellants to remove their patio as there was no cause of action to the Respondents to insist on a change of surface.

- Ground 1 was only briefly addressed by the Appellants before me and was put principally on the basis of their (and their predecessors') entitlement to maintain the Right of Way. In my view, the point was hopeless. The installation of a patio is not maintenance; it is the alteration of land, raising the height of the Right of Way through the introduction of paving stones for use as part of PTC's second garden.

- The Appellants also relied in their skeleton on the equitable maxim that "equity looks on that as done which ought to be done" to the effect that the court should presume that the disputed patio had been laid with the permission of the Respondents' predecessor in title. It does not appear that this point was argued before the judge but, even if it had been and therefore properly raised before me, it too is hopeless. The relevance of the maxim in this context was not explained but it appears wholly inapposite.

- Ground 6 discloses no real prospect of success.

- Finally, the Appellants relied under Grounds 7 and 8 on suggested procedural irregularities by the judge, as summarised below:-

- Save for limited observations, these grounds were not argued orally but the Appellants' essential points in their skeleton argument are that (i) the facts necessary to found an estoppel were pleaded (ii) the pleaded facts are to be treated as evidence (iii) despite the Respondents closing their case at trial, the judge could still have heard the estoppel arguments (iv) the evidence supports the conclusion that a proprietary estoppel operated here, the Respondents' predecessor in title having thanked the Appellants for telling them about the installation of an oil pipe, thereby creating an expectation that they could lay their pipe without later complaint or (v) alternatively, the Respondents' predecessors in title acquiesced in the Appellants' actions, standing by as they expended money on an oil heating system.

- Again, I have no hesitation in rejecting these grounds of appeal. I do so for a number of reasons:-

- Grounds 7 and 8 disclose no real prospect of success.

- None of the Grounds of Appeal discloses any real prospect of success. Nor is there any compelling reason why the appeal should be heard. I refuse permission to appeal. I invite the parties to agree a draft minute of order reflecting this disposal and any consequential matters arising.

Mr Justice Richard Smith:

Background

" … the dwellinghouse with the gardens, outbuildings and appurtenances ... more particularly described in the attached map or plan coloured green and yellow."

" … the right and liberty at all times for the owners and occupiers for the time being of the messuage and premises adjoining on the side of the property hereby conveyed to go pass and repass on foot only along over and upon the strip of land coloured yellow on the said plan".

The position of the boundary (Grounds 3-5)

Ground 3: On the basis of what the 1944 Plan plainly showed as to its correct position, the judge was wrong in law to find the boundary as she went on to order it.

Ground 4: The judge was also wrong in law to prefer one inadmissible expert report over the other on this issue.

Ground 5: Given these errors, the judge was wrong in law and/ or fact to conclude that part of (i) the brick wall did not belong to the Appellants (ii) the patio was on the Respondents' land and (iii) the Respondents' fence was not on the Appellants' land.

(a) that part of the yellow land abutting the east-west boundary wall was intended to be:-

(i) 4 feet wide where marked on the plan;

(ii) No less than 4 feet wide at the points marked 'A' and 'B'; and

(iii) Slightly wider than 4 feet wide at the point marked 'C'.

(b) the eastern end of the disputed boundary (point 'A') was intended to be at the north-western corner of the east-west boundary wall;

(c) the line from points 'A' to 'B' was intended to be a continuation of the line of the north facing face of the east-west boundary wall;

(d) the length of line from points 'A' to 'B' was intended to be the width of the 'hovels' at that point in the PTC southern garden. In 1944, that width was greater than 125% of the '4' 0' width where marked on the 1944 Plan and greater than one-fifth of the 26 foot frontage of FC. In other words, the distance from points 'A' to 'B' was intended to be greater than 5 feet; and

(e) the boundary line from points 'B' to 'C' was intended to kink slightly southwards at B (by perhaps 10 degrees) before continuing in a straight line which follows the northern wall of the then existing Earth Closet in PTC's southern garden and intersects the north-south boundary wall so as to be perpendicular to it.

Discussion on the position of the boundary

(i) The Appellants' approach to the evidence on this appeal differed markedly from that taken below;

(ii) Indeed, the Appellants sought to persuade the court below that it should use extrinsic evidence, including in the form of other available plans such as the 1994 HMLR survey plan in preference to the 1944 Plan;

(iii) Nor did the Appellants contend below that expert surveyor evidence was inadmissible, in fact relying on their own expert;

(iv) By changing their approach in such material respects, I agree that many of the considerations identified by Lewison LJ in Prudential Assurance Co Ltd v HMRC [2016] EWCA Civ 376 (at [23]-[24]) are engaged, militating against permitting such a changed stance being pursued on appeal;

(v) It appears, for example, to be envisaged that this court should substitute its own view of what the 1944 Plan shows, alternatively remit the case for re-consideration on a very different basis from that pursued by both parties below;

(vi) In any event, the Appellants' new arguments do not advance their substantive position. Although they now say that the 1944 Plan is unambiguous (save in one minor respect):-

(a) The 1944 Plan shows measurements along the Right of Way on the eastern side but not along the critical point at the western end;

(b) Ms Ellis-Greenway's opinion was that the 1944 Plan was not drawn to scale;

(c) Likewise, Mr Mycock's opinion was that, due to inaccuracies in scale, the 1944 Plan cannot be relied on to define the boundaries;

(d) Mr Mycock's own topographical overlay shows that some of those features present today and in 1944 are not shown in the same place as on the 1944 Plan;

(e) On any view, the judge was entitled to have regard to these matters, being concerned with what the 1944 Plan is (or is not) capable of showing;

(f) Those issues are compounded by differences between the two 1944 conveyance plans, namely the boundary line from point 'A', the eastern line of the hovels in the PTC southern garden and the area of the Right of Way at its western end;

(g) As such, the judge was entitled to conclude that the 1944 Plan was not accurate or reliable;

(h) She was also entitled to the reject the Appellants' position that the Right of Way did not change in width and was parallel along its length;

(i) The Appellants' assertions at the appeal hearing as to what the 1944 Plan shows (or what the use of a ruler might indicate as to the width of the Right of Way at a particular point on the boundary) were just that - assertion. They disclose no basis for going behind the judge's findings, let alone any error;

(j) Nor does the 1994 HMLR survey take matters any further given the limitations of the related plan which, again, the judge was entitled to find on the evidence; and

(k) In light of these matters, the judge did not fall into error by having recourse to extrinsic evidence for the purpose of establishing the boundary line.

Right of Way (Grounds 1 & 2)

Ground 1: The judge was wrong in law to find that the Respondents had by their (admitted) actions not caused a substantial interference to the right of way.

Ground 2: The judge was wrong in law to find that the right to "go and pass on foot only" did not include the right to wheel a wheelbarrow along the right of way.

"60. The authorities in relation to what is a substantial interference were set out following a review of the authorities by the Court of Appeal in Zielenewski v Scheyd & Anor [2012] EWCA Civ 247. At [10] of the judgment of Briggs LJ, as he then was, with whom Rix LJ and Moses LJ agreed, said the principles were "fully stated by Blackburne J in B&Q Plc v Liverpool and Lancashire Properties Ltd (2001) 81 P&CR 20 and in the dicta of Mummery LJ and Scott J there cited from West v Sharp (2000) 79 P&CR 327, at 332 and Celsteel Ltd v Alton House [1985] 1 WLR 204 at 217-218". The Defendants in this case rely on B&Q Plc. Briggs J restated those principles so far as were relevant to the case at [11]:

i) Not every interference with a right of way is actionable. The owner of the right of way may only object to activities, including obstruction, which substantially interfere with the exercise of the defined right as for the time being is reasonably required by him;

ii) The fact that an interference is infrequent and, when it occurs, is relatively fleeting, does not mean that the interference cannot be actionable;

iii) The question whether the owner reasonably requires to exercise his right in a particular way is to be addressed by convenience rather than necessity or even reasonable necessity – the question is can the right of way be substantially and practically exercised as conveniently as before?

iv) Thus, if an obstruction interferes with a particular mode of exercise of the right which is neither unreasonable nor perverse of the owner to insist upon, then the obstruction will be an actionable interference even if there remain other reasonable ways of exercising the right which many, or even most, people will prefer;

v) As Blackburne J put it in [B&Q [sic] Properties]:

"The test of whether an actionable interference is not whether what the grantee is left with is reasonable, but whether his insistence on being able to continue to the use of the whole of what he contracted for is reasonable."

"I would remark that it is sometimes thought that the grant of a right of way in respect of every part of a defined area involves the proposition that the grantee can object to anything on any part of the area which would obstruct the passage over that part. This is a wrong understanding of the law. Assuming a right of way of a particular quality over an area of land, it will extend to every part of that area, as a matter, at least, of theory. But a right of way is not a right absolutely to restrict user of the area by the owner thereof. The grantee of the right could only object to such activities of the owner of the land, including retention of obstruction, as substantially interfered with the use of the land in such exercise of the defined right as for the time being is reasonably required."

Ground 1 - discussion

Trespass (Ground 6)

39. The judge found that in this regard (at [57]) that " … the patio that the Claimants have installed and on which they have kept from time to time patio furniture and a gas cannister for a barbeque is on the Right of Way and so on the land of FC. Accordingly it is a trespass."

Grounds 7 and 8 (Estoppel argument)

Ground 7: The judge made a procedural error by preventing the Appellants from arguing estoppel in their closing submissions on the basis that the Respondents' Counsel had finished her closing submissions.

Ground 8: As a result of ground 7, the judge erred in law by finding that the Appellants' oil pipe was trespassing and ordering the Appellants to remove it.

(i) The Appellants' pleaded defence on this point was explicitly stated to be the defence of easement of necessity which, as the judge found, was only argued half-heartedly at trial;

(ii) The words acquiescence or estoppel do not feature in the Appellants' pleading;

(iii) The necessary ingredients for such an estoppel including (a) the Appellants' mistaken belief as to a right to lay the oil line (b) reliance (c) detriment and (d) unconscionability are also not pleaded;

(iv) The estoppel argument was only raised in submissions after the Respondents had closed their case;

(v) The Appellants' case in its appeal skeleton that the Respondents' predecessors in title "agreed to (and/ or acquiesced in) the installation of the oil tank and fuel pipe" goes beyond the Appellants' pleaded case that "no objections were received" or the evidence that their former neighbours thanked them for letting them know about the oil line;

(vi) It is not enough to say, based on a pleading plainly directed to a different defence, such evidence as did feature during the course of the trial which might be relevant to an estoppel argument and obvious inference, that the elements of the defence were made out such that the judge should have allowed the argument to be made;

(vii) To the contrary, allowing the Appellants to run what is a highly fact sensitive proprietary estoppel defence at the eleventh hour without advance notice and disclosure and witness evidence specifically directed to it, would have worked an obvious injustice on the Respondents. Permitting the Appellants to do so would itself have likely been a serious procedural irregularity;

(viii) There is no injustice to the Appellants by refusing to allow them to run this new case; they could have done so from the outset but they did not; and

(ix) In this regard, I accept the Respondents' submission that, had the Appellants done so, they would have conducted their defence of the case very differently.

Conclusion