Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

England and Wales High Court (Chancery Division) Decisions

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> England and Wales High Court (Chancery Division) Decisions >> Bockenfield Aerodrome Ltd & Anor v Scott Clarehugh [2021] EWHC 848 (Ch) (07 April 2021)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Ch/2021/848.html

Cite as: [2021] EWHC 848 (Ch)

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

BUSINESS AND PROPERTY COURTS IN NEWCASTLE

PROPERTY, TRUSTS AND PROBATE LIST (Ch D)

Newcastle upon Tyne. |

||

B e f o r e :

(sitting as a judge of the High Court)

____________________

| BOCKENFIELD AERODROME LIMITED |

Claimant |

|

| and |

||

| SCOTT CLAREHUGH |

First Defendant |

|

| and |

||

| LAURA CLAREHUGH |

Second Defendant |

____________________

____________________

Crown Copyright ©

HH Judge Kramer

1. The claimant is the leasehold owner and operator of an airfield at Eshott in Northumberland. It is represented by Mr Latimer, of counsel. The defendants are the owners and occupiers of land adjoining the airfield from where they operate a business trading under the style of Northumbrian Woodland Burials. As the name suggests, they provide a burial service for human and animal remains and ashes within a woodland setting. They are represented by Miss Jarron, of counsel.

2. The claimant complains that the growing of trees on the defendants’ land is interfering unlawfully with the use of their airfield. It frames its case in three ways, alleging that the presence of trees constitutes:

a. an interference with an express easement through the defendants’ air space in favour of their land. The claimant claims that the easement entitles aircraft from the claimant’s airfield to travel over the defendants’ land at a height which is safe for the aircraft. This requires that there is 20 feet of clear space beneath the aircraft, measured from the ground. Any incursion into that space amounts to an interference. The interference is substantial because the flight requirements of aircraft taking off and landing are such that they should have the facility of travelling at such heights over the defendants’ land but this has been prevented by the presence of the trees.

b. A derogation from the grant from which the title derives, namely a conveyance dated 2 February 1993 under which the airfield and easement were conveyed to the freeholder, which granted them their lease. The derogation arises from the presence of trees, the height of which, renders landing and take-off more difficult and also trees which disrupt airflow so as to have an impact on aircraft stability both when leaving and approaching the airfield runways but also when passing along the runways.

c. A breach of the measured duty of care.

The claimant seeks injunctive relief directed at the removal, and reduction in height, of certain trees and damages for loss consequent upon their presence.

3. The defendants’ response to the claim can be summarised as follows:

a. As regards the express easement:

i. It cannot be construed as having the meaning put forward by the claimant for it would have the effect of ousting the defendants from the land, which would render it incapable of existing as an easement.

ii. If it can exist as an easement, it should be construed in such a way that it permits pilots to fly at low level while arriving or leaving the airfield, but only at a safe height above what is on the land- not at a height which would permit pilots to approach the apron of the runway at an angle of 2.5 to 3°, as claimed by the claimant.

iii. Construed, as suggested by the defendants, the trees do not substantially interfere with the claimant’s use of the easement as safe landing and take-off is possible despite the presence of the trees.

iv. The defendants cannot be compelled to cut down trees to enable the claimants to use the easement as it is an essential characteristic of an easement that it does not place upon the owner of the servient tenement any obligation to act

b. As to the claim for non-derogation from grant:

i. There is no room for the operation of this principle because the parties to the 1993 conveyance set out in clear terms the grantor’s obligations in relation to overflying the retained land.

ii. A claim based on derogation by interfering with the airflow so as to cause turbulence was only added by amendment at the beginning of the trial and is not well supported by evidence.

iii. There has been no substantial interference with the use of the airfield, as such, to justify a finding of derogation from grant.

c. The measured duty of care does not arise in the circumstances of this case because:

i. It is not fair, just and reasonable to impose such a duty.

ii. The duty should not be extended to dangers posed by trees on the defendants’ land as these are natural things.

iii. The duty is a branch of the law of negligence. The tort of negligence requires damage to found a cause of action. There is no damage or threatened damage capable of founding a cause of action in negligence arising from the trees because the only damage to which the claimant could point would be pure economic loss due to its inability to operate the airfield, which does not qualify as damage for this purpose.

4. The defendants’ case as to the relief claimed is that they accept that if the grounds for an injunction are made out, this is not a case for ordering damages in lieu. Nevertheless, any injunction should be limited to the trees closest to the aprons of the northbound and eastbound runways.

Site Background

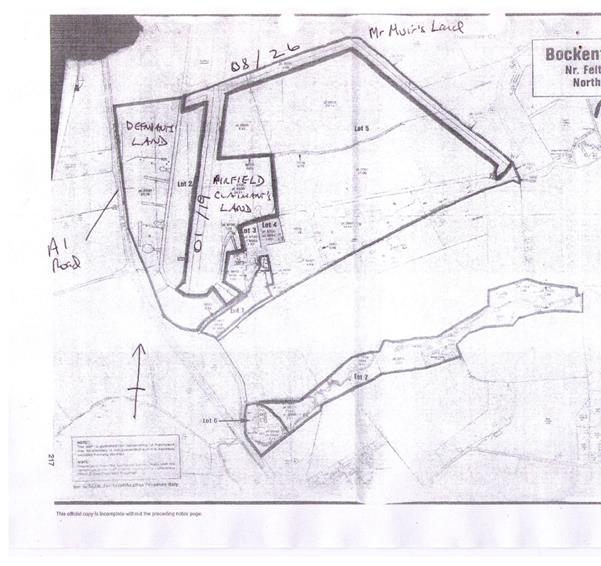

4. The history of the site is that both parties’ properties consisted of farmland, known as Bockenfield Farm. Between 1942 and 1944 runways were laid out on the farm for RAF Spitfire training. The relevant runways for present purposes are runway 08/26, which is the west/east runway, and 01/19, which is the north/south runway. At that time, the runways were much longer than those at Eshott airfield, running beyond the boundaries of the farm. In 1944 the whole of the land was returned to agricultural use.

5. The Bell family purchased Bockenfield Farm on 28 December 1984. They used it for sheep grazing and arable farming. In 1985 Mr P Bell, one of the owners, obtained temporary planning permission for part of the disused airfield to be used by single piston engined light aircraft. The permission was renewed in 1987 for a further period of 10 years and expressed to include ‘microlight aircraft’ within the expression ‘light aircraft’. There is unchallenged evidence that the airfield now operates under a full planning permission for aircraft up to a weight of 5700 kg and it is not suggested that it is still limited to piston engined aircraft. The Bell family reopened the airfield for the use of amateur pilots, their friends and families. I have been shown logbook entries evidencing numerous flights by Jim Shepard in a PA 28 aircraft between 1983 and 1985.

6. On 2 February 1993 the Bells sold the runways and some land adjacent to the north-south runway to Eshott Airfield Limited. They retained much of the remainder of Bockenfield Farm, including the land now occupied by the defendants. Paragraph 3 of Schedule 3 to the conveyance contains the following grant to the purchaser:“the unrestricted right to use at a safe height the airspace above the retained land for the passage of aircraft in circuit arriving or leaving the property.” The right is registered on the purchasers’ title, number ND80828. At the time of the sale the airfield was surrounded by open fields used in agriculture and some farm buildings. The land owned by the defendants was entirely open.

7. By a lease dated 20 June 2016, Eshott Airfield Limited leased the airfield to Bockenfield Aerodrome Limited for a period of 20 years. Clause 2.2 to the lease provides that the grant of the lease is made together with ancillary rights, including those intended to benefit the land subject to the lease and referred to in the register of title ND 80828. The right also appears on the register of the leasehold title, no. ND 188034. In addition to the right concerning over-flight, the lease included the benefit of an informal agreement with a neighbouring farmer, Mr Muir of Blackbrook Farm, to use an extension of the east-west runway at an annual fee. This was part of the old RAF runway which extended beyond the eastern boundary of Bockenfield Farm. The claimant’s subsequent loss of use of this extension has featured in the evidence.

8. The defendants’ land was acquired from the Bells by Stephen and Susan Clarehugh, the first defendant’s parents, on 2 November 1994. Its boundaries resemble the outline of a cone, the bottom of which bends to the east. They follow the eastern edge of the A1, its embankment and a layby, and to its east, runway 01/19 until it reaches 08/26, the westerly part of which runs across the end of 01 into the north-east edge of the top of the cone.

9. On 23 July 2001 Stephen Clarehugh obtained planning permission to use the land as a woodland burial ground. The permission was subject to conditions. No development was to start until a 10 metre hedge, which ran along the eastern boundary, i.e. adjacent to 01/19, had reached 2 metres and all other tree planting shown on a drawing attached to the permission had been completed. The trees are shown on the drawing as oak and ash. They are described in the planning officer’s report to the planning committee as a “40m belt of trees to the north and 50m belt of trees to the west, as a screen to the A1” The first defendant says that his father planted 16,000 trees on the site following the grant of planning permission. He and the second defendant have jointly owned and managed the site since 2015. The title is registered under number ND88406. He says that the number of trees have reduced to 12,000 due to woodland management. There is no dispute as to the number of trees originally planted or as currently in situ.

Site Layout

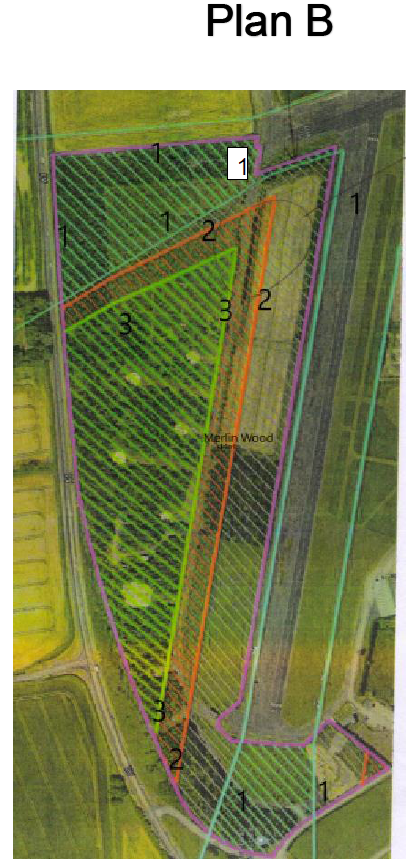

10. There are two plans attached to the judgment to assist with orientation. Plan A shows the parties’ respective holdings and the layout of the runways. Plan B is an overhead view of the defendants’ land and the adjacent runways. The darker areas, which appear as dark green on the electronic copy of the judgment, are those planted with trees.

11. There has been much mixing of metric and imperial measurements in the course of the evidence. I have retained the mix in the judgment in order to follow the evidence more closely, rather than convert all measurements to metres in the interests of uniformity.

12. The airfield has two operating runways. Those operating west/east are numbered 08/26 and those north/south, 01/19. The numbering refers to the magnetic compass bearing of the runway to the nearest 10°, with the last digit removed. Thus, runway 08 runs in compass direction 80°, i.e. west to east, and runway 26, compass direction 260°, east to west. It is 500 metres long and 12 metres wide. Runway 01, runs south to north and 19, north to south. It is 610 metres long and 12 metres wide. There is a grass runway adjacent to the east side of 01/19. Grass runways are required for aircraft which have a tail skid, as opposed to a rear wheel, and are preferred by planes which have rear wheel steering. Each runway is marked with its number, in paint, a few metres beyond the runway apron. The airfield is approached from the southbound carriageway of the A1, near Felton, Northumberland, via a road, described as a layby as it leads back onto the A1.

13. Beyond the end of runway 08 there is a fence on the boundary with Mr Muir’s land, behind which lies, on part of the old RAF runway , large numbers of straw bales and a piece of agricultural machinery which he said he put in place to warn incoming pilots of the presence of the fence and to prevent low flying. He took this action after terminating the claimant’s licence in 2019. To the north of runway 08/26 are the remains of the full width of the old RAF runway which lies on the land of yet another farmer, Mr Brown.

14. At the west end of 08/26 there is a fence marking the boundary with the defendants’ land. About 37 metres from the 08 runway marking, and about 60 metres further back, there is a wood which extends west to the defendants’ boundary with the A1 and thereafter runs south. The claimant alleges that trees in the greater part of this wood interfere with take-off from 26 and landing onto 08 and asks that almost all of them be removed. At the site view, some of the trees in the line nearest to the runway 08 measured about 23.5ft. There were also some shorter trees but further back in the wood a tree has been measured at 28.5ft, according to the claimant.

15. At the north end of runway 01 the land is open onto the adjoining farm beyond the claimant’s boundary. At the south end there is a boundary fence about 32 metres from the 01 marking. A further 61 metres to the south of the fence is the start of a wood which goes north and west, leading to the layby and the embankment to the A1. The trees here are said to be between 29 - 33 feet. The access road to, and over, the defendants’ land starts by running north west, along the northern edge of the wood, and turns north in a line parallel with 01, terminating along the boundary with 08. The claimant alleges that part of this wood interferes with landing on 01 and take off from 19 and seeks the removal of almost the entire wood. The defendants call this area Griffin Wood.

16. Slightly over one third of the way down 01, and on the defendants’ land, is a rectangular wood, called Merlin Wood. The claimant alleges that the presence of the wood produces turbulence to passing aircraft and seeks that about three quarters of the wood, starting immediately to the west of 01, be uprooted and that the remainder be kept to 10 metres in height. Mr Latimer indicated that the claimant does not seek the uprooting of any tree which covers human remains but such trees would need to be reduced in height; the claimant does not include trees marking the position of buried ashes within this concession.

17. Entering the defendants’ land from the layby one passes along the access road. Immediately to the left is Griffin Wood. This had been used for pet burials since 2018. Mr Clarehugh, the first defendant, says that it is made up of 592 mature trees, a small number of which have animal remains beneath. He says that removal of the trees would require the exhumation and relocation of the remains which would require permission of the Animal and Plant Health Agency. To the right of the road at this point are sheep paddocks.

18. Moving further along the access road there is Merlin Wood to the right, lying between the road and runway 01/19. This is used for interring ashes. Mr Clarehugh says that there are 356 trees in the wood and, at the time of making his statement, removal of the trees to ensure no regrowth would require removal of and the disturbing the remains of 51 people.

19. Passing further along the road, there is a space set aside for the construction of a crematorium, for which planning permission has been obtained. Beyond that, and to the left of the road is Clarefield Meadow which is used for coffin burials. According to Mr Clarehugh there are 3150 trees forming a woodland screen around the meadow and 170 mature trees directly on top of graves in which human remains are present. He says that to remove the trees from each grave would require the consent of the next of kin and an exhumation certificate from the Ministry of Justice. In the centre of Clarefield Meadow is Holly’s Garden in which there are buried 10 children. Notwithstanding that Mr Clarehugh says that it would cause outrage if any remains were disturbed, he told me he has not forewarned any of those with connections to the deceased about this case. I was concerned as to whether there were third parties who had a proprietary interest in the plots, as he referred to them having been purchased by those responsible for the burial, but he told me that all they acquired was a right to place the remains in his land.

20. Plan B shows the extent of the woodland which the claimant asks be removed or reduced. It seeks the removal of all trees between the lines numbered 1 on the plan and between lines 1 and 2. It requires that trees between lines 2 and 3 are reduced to 10 metres and maintained to not exceed that height and that all trees in the area bounded by line number 3 and the A1 are to be reduced to 15 metres and kept at no more than that height.

The issues

21. In broad terms there are 5 issues to consider. They are as follows:

a. How should the grant of the easement in the 2 February 1993 conveyance be construed?

b. In the light of the construction, have the defendants substantially interfered with the easement?

c. Have the defendants derogated from the grant constituted by the 2 February 1993 conveyance? This would include not just the grant of the easement but the conveyance of land which was to be used as an airfield.

d. Do the defendants owe the claimant a measured duty of care arising from the alleged hazard to the claimant posed by the trees, and if so, are they in breach?

e. If the answers to b, c, or d, establish that the claim against the defendants is made out,

i. what should be the claimant’s remedy and,

ii. in relation to b, c and d , has the claimant suffered damage in consequence and, if so, in what amount?

Construing an easement

22. The court’s approach to construing a conveyance is helpfully set out in Gale on Easements, 21st Ed at 9.20 as follows:

“The more important principles in this area can be summarised as follows:

(1) interpretation is the ascertainment of the meaning which the document would convey to a reasonable person having all the background knowledge which would reasonably have been available to the parties in the situation in which they were at the time of the execution of the document;

(2) the court will focus on the meaning of the relevant words in their documentary, factual and commercial context;

(3) the meaning of the words is to be assessed in the light of—

(a) the natural and ordinary meaning of the provision;

(b) any other relevant provisions in the document;

(c) the overall purpose of the relevant provisions;

(d) the facts and circumstances known or assumed by the parties at the time that the document was executed;

(e) commercial common sense;

(4) the process is an objective one in which one disregards subjective evidence as to the intentions of the parties;

(5) the general rule is that all relevant facts and circumstances can be taken into account as an aid to interpretation of the words used in the document;

(6) as an exception to the general rule referred to in (5) above, the court will not take into account the contents of pre-contractual negotiations save in so far as those negotiations reveal the existence of a background fact which is otherwise relevant;

(7) there is a further exception to the general rule referred to in (5) above where the document in question is only effective when registered in a publicly accessible register.

23. Only the 7th of these principles has proved controversial in this case, though, in the event, the disagreement as its application is of no consequence. Accordingly, I do not need to explore the width of the rule in detail. This exception to the general rule is to be found in the case of Cherry Tree Investment Ltd v Landmain Ltd [2012] EWCA Civ 736 where the Court of Appeal held that a facility agreement, which provided for the defendant to execute a charge in favour of a lender and that the money due thereunder became immediately due on execution of the agreement, was not relevant material to consider when construing the meaning of the subsequent charge which should have, but did not, make reference to this provision or the facility agreement, notwithstanding that the defendant was aware of its terms. The court was limited to looking at the background information which the reader of the register of title could reasonably be supposed to know. Mr Latimer argues that the decision was peculiar to the facts of the case and should not be looked upon as authoritative in dictating the court approach to the construction of an easement.

24. The editors of Gale do not agree with Mr Latimer’s assessment of the importance of Cherry Tree Investment and neither do I. It is clear from the judgment that the court was not formulating some special rule for the particular circumstances of Cherry Tree but was applying a well settled principle to the facts of that case. So much is apparent from the list of other circumstances in which the principle has been applied referred to by Lewison LJ at paragraph 125 of the judgment, and his reliance upon the articulation of the principle in Phoenix Commercial Enterprises Pty Ltd v Canada Bay Council [2010] NSWCA 64 and Attorney General of Belize v Belize Telecom Ltd [2009] 1 WLR 1988, at paragraphs 128 to 130 of the judgment.

25. Whilst the question as to what information can be taken into account as part of the factual matrix on the grounds that it was reasonably available to the parties has most recently be described as “a slightly controversial area”, see Rockliffe Hall Hotel Ltd v Travelers Ins Co Ltd CC-2020-NCL-000011 per Cockerill J at paragraph 32, the dispute concerning Cherry Tree is of no significance because although Miss Jarron referred to the decision and said that I should bear it in mind, she did not identify any of the background facts relied upon by Mr Latimer as being irrelevant to the issue of construction, following an application of the authority. Furthermore, Lewison LJ, at 130, recognised that physical features of the land are proper considerations when interpreting a transfer or conveyance. That is consistent with his reliance upon what was said in the extract he quoted from Phoenix Commercial, at 128, where Campbell JA said that the background knowledge which can be used as an aid to construction is such knowledge as “ is accessible to all the people who it is reasonably foreseeable might, in the future, need to construe the document.”

The construction of the express easement

26. It is convenient at this point to re-state the words of the grant. It appears in the property register for title ND80828 as:

a. “ The unrestricted right to use at a safe height the airspace above the retained land for the passage of aircraft in circuit arriving or leaving the property.”

27. The claimant’s case is that the “safe height” referred to in the grant is that which is safe from the point of view of the aircraft. The phrase “in circuit” is a term of art in aviation circles referring to the path which aircraft are expected to follow when approaching or leaving an airfield. These are rules of navigation which, just like rules of the road, enable the aircraft in the vicinity to know where each is expected to be. Mr Latimer argues that the ‘height’ is that which is safe for aircraft landing or taking off and that the court has to take into account the handling characteristics of light aircraft in construing what is meant by the term “safe height”.

28. Mr Latimer relies upon the claimant’s expert evidence as showing that where an aircraft has to undertake these specific tasks there are limits to how steeply it can approach the runway and take off in order to do so safely. Safety dictates that the pilot should aim to have a stable approach on landing and this requires a flight path which is at an angle about 3 degrees to a point about 10 feet above the numbers at the end of the runway. Obstacles at the end of a runway are hazardous because they force the aircraft to maximize the angle of climb which can promote a stall and are a risk to pilots overshooting the runway, if faced with mishaps such as an engine failure, or having to abort a landing and go around again, i.e. gain height and speed so as to return to the circuit and attempt a further landing. The safety factor available to aircraft as they cross the defendants’ land should be 20 feet of clear airspace beneath, if possible, though it will be less as it passes over the boundary between the two properties. Drawings have been provided by the claimant which show that to achieve 3 or 4 degree rates of descent and a 20 foot safety margin would require that many of the trees on this flight path would have to be removed or markedly reduced in height.

29. Against this background the claimant asked me to construe the easement as conferring upon it a right to take off and land over the defendants’ land through an air corridor which permits landing at 3 degrees and provides a clear area beyond the runway which enables a plane to overshoot without coming into collision with any obstacles. It is said that there are circumstances surrounding the grant that favour such a construction. In particular, I am asked to take into account that at the time of the grant the defendants’ land was open fields, the vendor was operating the airfield for the use of amateur pilots flying light aircraft, there was planning permission for this purpose in force for aircraft of the type used by the claimant, and a PA 28 aircraft is known to have been using the airfield, as is apparent from an airfield log book produced in evidence. In addition, Mr Latimer argues that the statutory provisions and the common law concerning the use of airspace further supports the construction relied upon by the claimant.

30. Miss Jarron’s starting point is that the easement is one which permits that which would otherwise be a wrong against the defendants, as servient owner, namely to fly in circuit over their land which, she argues, would otherwise be a nuisance and trespass. The defendants’ case is that the grant permits flight over the defendants’ land and all the other retained land referred to in the 1993 conveyance, when in circuit, in order to land upon or take off from the claimant’s runway. There is no limit to the number of planes that can take off and land during the day or at night, that being the relevance of the reference to an “unrestricted right to use”, but they can only fly at a height which is safe from the point of view of the people, machinery and buildings below. It does not permit flying at low level such as to endanger those on the ground. The grant permits the aircraft using the aerodrome to pass over the defendants’ land at a safe height above the trees but it is up to the pilots to maintain a safe height taking into account what is below them.

31. The defendants ask me to take into account a number of factors when construing the grant. Miss Jarron points out that the right was granted over all the retained land, not just that owned by the defendants, so should not be interpreted differently from the right as it affects other retained land. As other parts of the retained land were built on at the time of the grant, it cannot permit surface level flying. It only permits flight at a height which is safe having regard to what is on the ground. The meaning is reinforced by the fact that no reasonable pilot would want to fly at an unsafe height, thus the reference to use at a safe height is a qualification to the grant not an additional benefit to the grantee.

32. I was referred to the defendants’ expert evidence which, it is said, demonstrates that light aircraft can land at steeper angles than 3 degrees and there is no requirement that they land at this angle. The expert relies upon the Aeronautical Information Circular 127/2006, issued by the Civil Aviation Authority on 7th December 2006 which provides that on take-off the pilot is expected to calculate the adequacy of the runway on the basis that they can pass the threshold of the airfield at 50 feet. A similar calculation is required for landing. Thus, it is argued, the air corridor which is subject to the grant must take into account that any aircraft will already be at 50 feet as it leaves the airfield. Further, at the time of the grant the airfield was used by microlights and light aircraft. Miss Jarron places reliance on the terms of the proposal for planning permission in 1984 which indicated that use was sought for single piston light aircraft with a condition that aircraft were not to be used between 7pm and 9am, which proposals were carried into the permission. At that stage there was no licence to provide training at Eshott though now the claimant prays in aid the fact that the trees should be removed as less experienced and student pilots may find it too challenging if they have to manoeuvre over the trees.

33. Miss Jarron argues that the claimant’s construction must be incorrect because if the grant permitted aircraft to overfly at a height so low as to achieve a 3 degree angle of approach, the defendants could not use their own land due to the danger of aircraft colliding with vehicles or those working on the land. She referred me to Reilly v Booth (1890) 44 Ch D 12 as authority for the proposition that there is no easement known to law which gives the dominant owner exclusive and unrestricted use of a piece of land. She further argues that an easement cannot impose a burden on the servient owner to accommodate the rights of the dominant owner, such as by cutting down trees, for the character of an easement is such that it requires no more than sufferance on the part of the servient owner; she referred me to Jones v Price [1965] 2 Q.B. 618 and Moncrieff v Jamieson [2007] UKHL 42 in this respect.

Discussion and conclusion on the construction of the grant

34. The legislative and common law governing the use of airspace over land is relevant to the issue of construction as it is the legal background against which the grant was made. Furthermore, the parties to the 1993 conveyance can be taken to have included the grant for some purpose, namely to enable the owner of the aerodrome to do something which it could not do otherwise. What are the rights of a land owner in relation to the airspace above their land and of aircraft to pass through that airspace?

35. The parties accept that, on the authority of Bernstein v Skyviews & General Ltd [1978] 1 QB 479 the rights of the owner are restricted to “the air space above his land to such height as is necessary for the ordinary use and enjoyment of his land and the structures upon it, and…above that height he has no greater rights in the air space than any other member of the public” see per Griffiths J (as he then was) at 488A. Flight over the property of another above such height does not constitute a trespass to airspace or, without more, a nuisance. Overflight which interferes with the reasonable enjoyment of land, such as by making unreasonable noise or of unreasonable frequency could amount to a nuisance. That was the position at common law at the time of the grant.

36. Section 76 of the Civil Aviation Act 1982 provides:

“(1) no action shall lie in respect of a trespass or in respect of nuisance, by reason only of the flight of an aircraft over any property at a height above the ground which, having regard to wind, weather and all the circumstances of the case is reasonable, or the ordinary incidents of such flight, so long as the provisions of any Air Navigation Order and of any orders under section 62 above have been duly complied with and there has been no breach of section 81 below.”

Section 62 related to the control of civil aviation in time of war and emergency and section 81 concerned dangerous flying. They are of no relevance here.

37. The Civil Aviation Act 1982 empowers the Secretary of State to make Air Navigation Orders by way of statutory instruments. Such orders permit the Secretary of State to make the Rules of the Air which are to be followed by those piloting aircraft. The rules used to provide that aircraft must keep 500 feet above people except for take-off or landing. The most recent Rules of the Air, which took effect on 25 March 2020, require pilots to keep to a height of at least 500 feet above the ground or water or the highest obstacle within a radius of 500 feet from the aircraft save when passing over assemblies of people or cities, towns and settlements where a greater height must be maintained and save when landing or taking-off.

38. The instructions contained in the 2006 Aeronautical Information Circular as to screen height are not relevant to the construction of the grant first, because it does not require that aircraft pass over the runway threshold at 50 feet and secondly, because the 2006 instruction cannot have been in the contemplation of the parties in 1993. I consider the true impact of the AIC 2006 in greater detail when looking at the issue of substantial interference.

39. In the light of the common law and statutory restrictions on overflying, the grant may be seen to have been necessary to enable pilots on circuit and prior to coming into land, and after take-off, to overfly the servient land at heights and with a frequency which may otherwise have been actionable.

40. The other relevant factual background is that at the time of the grant the demised land was being used as an aerodrome for light aircraft by the vendor and there was planning permission for this purpose. The runways at the time of the grant were the same length as they are now. The airfield has always been one at which pilots land by sight and can be expected to adjust their flight paths by reference to what they observe. Evidence of use by a particular PA 28 aircraft prior to the transfer may fall within the Cherry Tree category of evidence not available to third parties, this point was not argued, but what is undoubtedly relevant is that the runways were, and are, of a length which can accommodate such aircraft. The airfield was surrounded by open farmland. Whilst there were some farm buildings on parts of the demised land, the areas leading to and from the runways were not built upon. There was nothing to prevent aircraft using the two runways from landing or taking-off at low heights over the servient land, subject to the need to ensure the safety of those on the retained land by keeping a safe distance from both people, animals and agricultural machinery, but being agricultural land, their presence would have been intermittent. Aircraft in circuit would also need to avoid the buildings on other parts of the retained land.

41. Mr Latimer argues that account must be taken of his expert evidence to the effect that there is a maximum height over the servient land at which a light aircraft must be able to fly in order to land at a 3 degree angle of approach so that anything which reduces the airspace within that height must be removed. This is relevant, however, if the reference to a “safe height” means one that is safe for the aircraft as opposed to those on the ground. Given that at the time of the grant there would only have been transient obstacles liable to have been on the defendants’ land, there was no need to include such a provision for the benefit of aircraft for there was no permanent physical restriction preventing low flying.

42. I agree with Miss Jarron that the pilots can, and must, decide what amounts to a safe height at which to fly. I also agree with Miss Jarron’s submission, on the authority of Reilly v Booth (above) that as this was expressed as the grant of an easement, it cannot have been intended to prevent a use of the retained land by the servient owner for general agricultural purpose which may entail, for example, the presence of people, animals, farm machinery and such other materials as one might expect to find on agricultural land. If they could not use their land at all due to low overflight they would be excluded from the land and that state of affairs is not consistent with the existence of an easement or the fact that the way was granted over agricultural land. Furthermore, a right to overfly which permitted the dominant owner to fly at heights which were dangerous to those on the ground is most unlikely to represent the objective intention of the parties to the transfer. A court is slow to impute to the parties an intention to produce an absurd situation, as this would be; Gardner & another v Davis and another, Court of Appeal (unreported) 15 July 1998, [1998] Lexis Citation 3106 per Mummery LJ at p.9, a case concerning the construction of an easement of drainage.

43. The people who need the protection inherent in the requirement that flight is to be at a safe height are those on the ground who have no other control over the danger posed by overflight, not those in control of the aircraft. The evidence concerning angles of descent is relevant to the questions as to whether the trees now in place constitute a substantial interference with the easement, derogation from grant or breach of the measured duty of care, but not the construction of the grant, for at the time of the grant there was nothing to prevent pilots from flying as low as they chose, save for the requirement to fly at a safe height.

44. The objective observer with the relevant background information would have concluded that the grant permitted aircraft from the airfield to fly over the defendants’ land within the airspace which would otherwise amount to a trespass or nuisance, whilst in circuit or in the process of landing or taking off, provided they maintained a height above the ground and buildings, as matters stood at the time of the grant, which was safe for people on the retained land, such animals and other machinery, materials and crops as one would expect to find on agricultural land and the buildings on the retained land.

45. Such a construction precludes the claimant’s suggestion that the easement includes the right to use the defendants’ land as a run-off area to protect pilots from error or mishap. Although not put in those terms by Mr Latimer, it was inherent in the claimant’s complaint that aircraft overshooting the runway are liable to collide with the boundary fence and trees if they fail to leave the ground or take off too far down the runway. The easement provides for overflying at a safe height. That cannot include trespass on to the surface of the defendants’ land or, for whatever reason, passing over it at heights which are unsafe in the sense I have indicated.

46. What amounts to a safe minimum height will vary according to what is on the ground at any particular time, for of its nature, agricultural land will be used by machinery of varying heights, so what may be a safe height on a day when there is a wagon or a tractor being used on the land may be different on a day when there is not. The pilots have to set their height to take such transient conditions into account. They cannot rely on the “easement as justifying what would otherwise be a trespass because the easement is not, in fact, being fairly or properly exercised” per Parker J in Jones v Pritchard [1908] 1 Ch 630 at 638. The pilot is in no different position from the dominant owner driving along a right of way. The right must be “fairly or properly exercised” and this requires that they take into account the safety of others entitled to be on the way, including the servient owners. The question as to what amounts to a safe height at which to clear the ground or people, equipment and other materials on the ground, is answered by the expert evidence and can be considered alongside the issue as to whether the defendants’ trees substantially interfere with the easement.

Have the defendants substantially interfered with the claimant’s use of the easement?

47. The law as to what amounts to an actionable interference is not controversial. The principles were set out by Briggs J (as he then was) in Zieleniewski v Scheyd [2012] EWCA Civ 247 at paragraph 11, where he said:

“ For present purposes the applicable principles may be summarised as follows:

1. Not every interference with a right-of-way is actionable. The owner of the right may only object to activities, including obstruction, which substantially interfere with the exercise of the defined right as for the time being is reasonably required by him.

2. The question whether the owner reasonably requires to exercise his right in a particular way is to be addressed by reference to convenience, rather than necessity or even reasonable necessity.

3. Thus, if an obstruction interferes with a particular mode of exercise of the right which it is neither unreasonable nor perverse of the owner to insist upon, then the obstruction will be an actionable interference even if there remain other reasonable ways of exercising the right which many, or even most, people would prefer.

As Blackburne J put it “The test of an actionable interference is not whether what the grantee is left with is reasonable, but whether his insistence on being able to continue the use of the whole of what he contracted for is reasonable.”

48. The claimant has adduced lay evidence of interference from pilots who have used the airfield. In addition, the claimant relies upon expert evidence from Kenneth Fairbank.

49. The lay evidence can be dealt with in summary. Stephen Slater is the chief executive of the Light Aircraft Association. He has been a pilot for 20 years. He last flew at Eshott in July 2019. He said that the usable length of the runway was reduced because of the obstacles, by which he meant the trees, in particular, those to the west of runway 08. He said this was not the principal runway he used due to the obstruction created by the trees. On landing, he attempts to approach at an angle of between 3 to 5 degrees but the trees erode the amount of airspace he has available. He did not have difficulty when he last flew into Eshott in July 2019 because he was flying a vintage Auster aircraft which can land steeply and over a short distance. Nevertheless, on that occasion he used runway 1/19 as it gave a little bit more space and thus permitted a safer approach.

50. Ian Parkinson has been a pilot for 35 years. He has flown from Eshott since the late 1990s. When he first operated from Eshott there were no trees adjacent to the airfield and when they were initially planted they caused no problem as they were very low to the ground. He said that the first defendant’s father, Steve Clarehugh, had told him in 2001 that he was paid to put the trees in and in due course he would be paid to remove them. It was suggested to Scott Clarehugh that this was evidence of some long term plan to avenge a disagreement he had with the airfield owners at the time but I take the view that this is utterly implausible given the timescale involved. In fact, Mr Parkinson said that Stephen Clarehugh had a good relationship with the former owner of the airfield, Storm Smith, and he continued to fly at Eshott until his untimely death in a road traffic accident.

51. Mr Parkinson’s experience in the period after the trees developed in height is that when using runway 08/26 he can no longer take a full tank of fuel if there are more than two people on board his plane because he does not have adequate room on the runway to ensure he has sufficient lift to take off and clear the trees. This has been a particular problem over the last two years. On landing, he has clipped the trees on the defendants’ property, when coming into land, and he has not been able to land on the first quarter of the runway due to the angle of descent required consequent upon the presence of the trees. The ideal approach for his type of aircraft is one of a 3 degrees. He used to fly approximately 100 hours a year but, lately, this is been much restricted due to the presence of the trees.

52. Derek Wright is a commercial airline pilot who has been flying for about 37 years. He also said that his desired angle of approach is 3 degrees. At that angle the trees obscure the view of the threshold of the runway and you cannot see the numbers. When landing on 08, in order to land as close to the beginning of the runway as possible, a sudden increase in speed and rate of descent is required at a late stage once the painted numbers become visible. This has the effect of destabilising the approach. When taking off towards the west he limits his fuel load and passenger numbers to ensure he has an extra safety margin so as to clear the trees. Based on his recent flights from Eshott, the situation was much more serious than it had been approximately six months before his statement, that being dated 18 September 2020. He uses Eshott approximately three times a month. His aircraft can be caught in turbulence on take-off and landing which is exacerbated by the presence of the trees. He produced a video showing him landing on 08 which, he said, indicated that he was about 60 feet above the airfield when landing, which was significantly higher than ideal and caused him to land further down the runway than would be best practice.

53. Mr Pike and Mr Woodgate both gave evidence that the presence of the trees at the ends of the runways interfered with the passage of aircraft in that they rendered take-off and landing unsafe and removed the scope for aircraft to overshoot the runway or to take off from far down the runway in the event that they had to abort a landing. Mr Pike also exhibited some online comments from two individuals who were supportive of the contention that landing was difficult because of the presence of trees. Mr Woodgate spoke of his own experiences of turbulence produced by the trees at the end of the runway reducing lift and the difficulty in taking-off and landing due to the height of the trees. There are features of these witnesses’ evidence which caused me to be concerned that they were unreliable, but in relation to their evidence of their experience of flying in the vicinity of the trees they are supported by the three other pilots from whom I heard.

54. Mr Pike produced a safeguarding chart for the area around the airfield, as support for the removal of the trees, which he said recommended that there should be nothing above ground level. On questioning Mr Pike, however, it appeared that this document is prepared for planning authorities to trigger an enquiry if permission is sought to develop in the vicinity of an airfield. There is no legal requirement that nothing can be built on land in the safeguarding zone, indeed, the crematorium planned for the defendants’ land, and which has the claimant’s support, is within the zone. In the light of that explanation, the safeguarding map is not relevant to the questions I have to decide.

55. Both Mr Pike and Mr Woodgate referred to an accident which occurred on 26th October 2018 in which a trainee crashed a Piper PA28 Cherokee aircraft as it was landing on runway 26. Mr Woodgate claims that the pilot said that he had landed too far down the runway due to mechanical turbulence and he jammed on the break in panic as he was unable to “go-around” due to the presence of the trees. I shall deal with the evidence concerning the PA28 when I look at the issue of damages. For the present, it is sufficient to record that I do not accept the evidence of Mr Pike or Mr Woodgate to the effect that the presence of the trees contributed towards the crash. I shall also deal with their evidence concerning the crash of another aircraft, a Kitfox, when considering damages. I do not regard what happened to the Kitfox as relevant to the issue of the interference with the easement or other pleaded causes of action.

56. Mr Woodgate gave evidence as to the measurement of the trees. He said that in the line of trees nearest the defendants’ land from runway 08, there were trees 23.69ft in height and further back there were trees to a height of 28.54ft. As regards the defendants’ land to the south of runway 01, the trees ranged from 29.46ft nearest to the runway and rose to 33.66ft further back. At the site view a tree in the line closest to runway 08 was measured and the measurement produced broadly matched Mr Woodgate’s evidence in relation to that area.

57. The defendants’ factual evidence as to the ability of aircraft to take-off and land notwithstanding the presence of the trees was limited. Mr Clarehugh said that microlights and light aircraft under 2730Kg had used the airfield for years and there had been no issues with take-offs and landings. He referred to an event in 2016 called Fly the Tyne where large numbers of light aircraft and microlights took off and landed without incident. In cross-examination he accepted that he was not aware that the weight limit for aircraft was 5,700kg.

58. Mr Clarehugh gave evidence as to the type of machinery which could be expected on his land, the largest of which, a digger, measured 16 feet in height. He considers that any aircraft flying over his land at 30ft or less is a danger to those on the land. He was also cross-examined at length as to what had been agreed with the claimant as to the cutting or removal of trees. Other than to note that his responses did not always seem consistent with the emails dealing with this subject, such evidence was of no assistance. Mr Clarehugh did give important evidence concerning the claim for loss to which I shall refer when dealing with that issue.

59. There was further evidence about Fly the Tyne events from Douglas Coppin, who was called by the defendant. He is a member of the British Microlight Aircraft Association (BMAA) and a microlight pilot and inspector. He organised these events in 2016 and 2018 and said that of the 110 pilots who took part none complained about the trees- he did not fly on either occasion as the organiser is not permitted to fly. When describing these events, during cross-examination, it was apparent that the aircraft concerned were micro-lights apart from one Cessna 150. Aircraft took-off from runway 01 and banked to the left over the defendants’ land. He said that his microlight was hangered at Eshott from December 2012 to August 2015 during which time he organised another event called Eshott Escapades where 20 competition pilots undertook a number of skills tests and none raised issues about the trees. He stopped flying from Eshott in 2018.

60. Mr Coppin started his responses to cross-examination by saying the BMAA does not support the claim. That was an unpromising start as his role was to provide factual evidence relevant to the flying of aircraft in the presence of the trees rather than to convey the stance taken by an organisation of which he is not an officeholder and upon whose behalf he had not been asked to speak; there was no evidence from BMAA itself that it had anything to say on the subject. Furthermore, he told me. quite unnecessarily, that there had been an incident involving Mr Pike’s aircraft in the South of France where two people had died. In these two respects, Mr Coppin does appear to be a partial witness so I have to be careful in evaluating his evidence.

61. The defendants also relied upon the evidence of Mr Bell who, with his family, had sold the airfield and granted the easement, and Mr Muir the adjoining farmer. Much of Mr Bell’s evidence was inadmissible, insofar as he sought to explain what he had sought to achieve when granting the easement. He was, however, able to give background evidence as to the use of the airfield both prior to and at the time of the sale.

62. Mr Muir’s evidence did not go to the issue as to whether the trees on the defendants’ land were an obstacle to safe flight. It was concerned with explaining why he had terminated the licence to use part of the runway on his land and demonstrating that he had suffered from low and dangerous flying, an arson attack on hay bales he had placed on his land to mark his boundary, theft of a tractor key by Mr Woodgate and the subject of a malicious report to the police that he was endangering aircraft.

63. Mr Pike sought to deal with these allegations by making completely unnecessary allegations of fraud against Mr Muir which were pursued in cross-examination. These allegations were supported by nothing more than Mr Pike’s word, which, for reasons which I deal with later, did not seem to me to carry much weight. Mr Muir denied any wrongdoing and, since these matter were raised, I consider it necessary to say that these allegations were not made out. As regards an allegation by Mr Woodgate, that Mr Muir and his wife had staged an accident in which she whipped her horse so as to throw her in order to pin the blame on low flying aircraft, I consider it is inherently implausible. Mr Muir’s evidence as to the malicious report to the police, the burning of his hay bales and the theft of his tractor key are supported by photographic and other documentary evidence. As regards his denials of fraud and staging an accident, I prefer his account of events where it differs from that of Mr Pike and Mr Woodgate.

The expert evidence

64. The claimant’s expert, Mr Fairbank, is a specialist in air accident and incident investigation, flight operations and commercial flight crew training. He has 40 years’ experience in aviation. He was well qualified to provide an opinion as to the effect of the presence of the trees on the movement of aircraft. He described what a pilot is trying to achieve in the course of landing.

65. First, it is desirable to have a stable approach and maintain a steady speed. Secondly, the pilot will want to have as much of the runway available as possible. When flying by sight, as is the case at Eshott, a pilot will seek to aim for the numbers at the end of the runway, passing over them at about 10 feet. As the aircraft gets close to the runway the pilot pulls back on the controls to level the line of flight. This is called the flare. From there, the pilot will allow the aircraft to descend towards the runway by reducing the power but holding up the nose. This permits the aircraft to make contact with the ground as the speed decreases. Steeper angles of approach are liable to produce instability because the aircraft’s speed will increase in the descent, is thereby more difficult to control and it is more difficult to judge when to flare resulting in a hard or premature touchdown. Any misjudgement at this stage can result in the aircraft floating for an extended distance thereby needing more runway. In his report he suggested that an angle of 3° represents a good compromise for an angle of descent, though in evidence he accepted that a range of approaches between 3° and 4.5° were workable although at 5° there were aircraft which might struggle.

66. As regards an adequate safety margin, Mr Fairbank was of the view that the pilot should have a 20 foot gap of airspace above any obstacles situated below. The claimant produced some helpful scale drawings illustrating the height of the aircraft at 3° and 4° rates of descent for both runways relative to the trees and boundary fence. These show that landing at 3°, an aircraft travelling from the south onto runway 01 would first pass over the defendants’ land at 34.76 feet, pass the northern face of the first plantation at 26.02 feet and clear the boundary fence at 15.6 feet in order to reach a place 10 feet above the numbers. At 4° the figures would be, in the same order, 43.04 feet, 31.38 feet and 17.48 feet. For runway 08 at 3° the aircraft would encounter the trees bordering the A1 at 55.56 feet, pass over the eastern face of the trees closest to the runway at 19.94 feet and the boundary fence at 16.41 feet in order to reach a point 10 feet over the numbers. At 4° the equivalent figures are 70.8 feet 23.26 feet and 18.56 feet. These figures were not subject to challenge.

67. Mr Fairbank expressed the opinion that the trees on the defendants’ land interfere to a significant extent with the unrestricted right to use the airspace above their land. The trees presented a safety concern. The angles currently required to clear the trees with a safe margin on landing are far in excess of what he would consider normal.

68. On take-off and landing pilots are likely have to make modifications to standard take-off and approach profiles, special techniques which would not be required if the trees were not there or reduced in height. The height of the trees denied pilots essential visual cues. Some aircraft, which would otherwise be able to the use the runways, are prevented from doing so by the presence of the trees; this was a reference to the performance characteristics of three types of aircraft, a PA 28, Cessna 150 and EV 97 Eurostar. Applying safety factors recommended by the civil aviation authority for take-off and landing, based on tree heights of 30 feet and allowing a margin to clear the trees of 20 feet, the EV-97 could achieve a sufficient height, the Cessna’s ability to reach an adequate height was marginal and the PA 28 was unable to clear the trees and required an extra 20% of runway. In cross-examination he said that these calculations were based on the maximum weight of the aircraft but the performance could be improved by reducing weight. It is common ground that this is usually achieved by limiting the fuel or number of passengers on board. Using the same safety margin for landing, i.e. clearing 30 foot trees by 20 feet, the EV-97 could not land in the distance available using the distance from 50 feet, the Cessna 150 and PA 28 could, but the latter took up 89% of the landing distance available. The trees require pilots to land further down the runway, increasing the risk of a mishap. The trees also interfere with the ability to use the airfield for training as this requires flying to normal standards, i.e. not having to adopt special techniques.

69. The principal evidence upon which the defendants relied in disputing the allegations concerning the impact of the trees upon aircraft was the expert evidence from Captain Kingswood. He has over 40 years of experience in aviation, first in the RAF, subsequently as a commercial and private pilot, in the training posts he has held and in Air Accident Investigation and as the safety officer for a flying school. He too was well qualified to provide expert opinion on the impact of the trees.

70. Capt. Kingwood is of the view that the trees are not an obstacle to safe take-off and landing for a number of reasons. First, there is no general aviation requirement for light aircraft to land at approach angles of 2.5° to 3°. Secondly, light aircraft are capable of landing at very much steeper angles and these are often required when, for example significant headwinds are present, when the angle can be in the region of 6° to 8°. Thirdly, aircraft taking off should achieve a height of 50 feet by the end of the runway, called the screen height, thus there is no prospect of them coming into contact with the trees. The pilot is required to ensure that there is sufficient runway to be able to reach this screen height on take-off and to land from a screen height of 50 feet; Captain Kingswood relies on Aeronautical Information Circular (AIC) 127/2006 issued by the Civil Aviation Authority which contains recommendations for calculations made by reference to the performance data of aircraft models and various other factors to ensure that based on a 50 foot screen height there is adequate runway for a safe take-off and landing. He says that the legal obligation on the pilot to take-off and land safely can be discharged, as regards demonstrating that there was adequate runway length, by performing the recommended calculation.

71. Capt. Kingswood said that Eshott was no different from several unlicensed airfields around the country as regards the presence of trees. He referred to Civil Aviation Publication (CAP) 738 entitled ‘Safeguarding Aerodromes’. The document provides guidance to airfield operators on planned developments. He pointed to those parts of CAP 793 indicating that an aerodrome safeguarding map is for guidance only, its purpose being to indicate areas in which development could affect aerodrome operations, that the operator of an aerodrome must suspend their operations if an obstruction has been positioned in the path of an aircraft. In the chapter dealing with aerodrome physical characteristics, there is a recommendation that runways should be designed so that trees, power lines, high ground and other obstacles do not obstruct its approach and take-off paths. It is also recommended that there is no obstacle greater than 150 feet above the average runway elevation within 2000 metres of the runway midpoint.

72. Reference was also made to Article 209 of the Air Navigation Order 2016 which places the legal responsibility for the safe operation of aircraft on take-off and landing on the airfield operator and the pilot in command. He sought to draw the conclusion that continued operations at the airfield indicated that the claimant considers that the current environment at the airfield offers appropriate levels of safety to aircraft and that the current growth height and location of the trees is within the guidance set out in CAP 793. He also suggested that the fact that the claimant had not referred to the trees in a pilots guide to airfields, Pooley’s Guide, is an indication that the claimant does not regard the trees as presenting a hazard to aircraft using Eshott.

73. As regards the accident involving the PA 28 aircraft in 2018 he was of the view that the presence of the trees played no part. There was a light west north-westerly wind on that day, thus any buffeting experienced by the pilot was not the result of wind passing over the trees on the defendants’ land. He points to the contents of the report on the accident by the Air Accidents Investigation Branch (AAIB). There is no reference in the report to the pilot expressing concern about the trees. He said that he had touched down later than normal and in a panic to stop slammed on the foot breaks. The experience had taught him the importance of discontinuing the approach and going around if he was not happy with any of the flight parameters. The AAIB commented that runway 26 is shorter than runways typically used for ab initio training and landing and such runway could be considered as challenging for an early soloist. Capt Kingswood was of the view that the crash was as a result of a mishandled approach and poor decision-making which, he said, is often a factor during pilot training.

74. Capt Kingswood was asked to consider the operation at Eshott of particular types of aircraft, a PC 12, which is a turboprop, and a Harvard, a training aircraft used to train fighter pilots during World War II. Applying the 50 foot screen height and the factors set out in AIC 127/2006, he reached the conclusion that the PC 12 could not take off and land at its maximum permitted take-off weight. The aircraft could use runway 01/ 19, even in a crosswind although the width of the runway, at 12 m, would have a risk attached as it is 4 metres narrower than the wingspan of the aircraft. He thought the airfield would be marginal for PC 12 use. As regards the Harvard, safe operation would not be possible at Eshott if the AIC safety factors were applied due to the length of the runways, not the presence of trees.

75. There was a large measure of agreement between the experts in the joint report. In particular, they agree that approach angles steeper than 3° are acceptable in general aviation but there is a limit as to how steep they can be depending on wind conditions and aircraft type. It will be in excess of 3°, but it is difficult to establish a maximum figure. Certain types of aircraft, typically heavier and faster types, will always be limited in using Eshott regardless of the trees. Pilots have a legal obligation to check that the aeroplane has adequate performance for the proposed flight. The use of the safety factors in AIC 127/2006 is accepted as best practice and the 50ft threshold crossing height is one of the criteria used for determining the length of runway required. There is no requirement that landing aircraft must cross the runway threshold at no less than 50 feet nor that on take- off they must reach that height by the end of the runway.

76. The experts disagree as to whether it is optional or mandatory to perform the distance to landing and to take-off calculations; Mr Fairbank suggest the former and Capt. Kingswood the latter. Mr Fairbank considers that the trees are an obstacle to landing as they force aircraft to approach at a steeper angle which might preclude an aircraft from landing or increase the risk of running out of runway. They are also an obstacle to take-off as the pilot will need to refer to the take-off distance to 50 feet in the performance data for the aircraft to ensure adequate clearance over the trees, and this may impose penalties, by which he means measures such as lightening the load; the 50 feet clearance data is based on his suggestion that a pilot would need to clear 30 feet trees by a further 20 feet in order to pass at a safe height.

77. Capt. Kingswood opinion is that the trees do not interfere with landing or take-off as the pilot has to calculate the sufficiency of the runway length by reference to arriving and leaving 50 feet over the runway threshold. If that can be achieved, there is no need for a plane to be flying near to the trees or to achieve an over steep landing. He accepted calculations put forward by Mr Fairbank which show that an aircraft passing over the trees to the west of runway 08 would lose 43% of runway , at 3° degrees, and 21% at 5 degrees, if it flew at 50 feet at the trees but says that the 50 feet, based on a 30 foot tree and 20 foot clearance, is an arbitrary figure as there is no need to clear the trees by 20 feet, 10 feet would be sufficient, steeper descents can be managed, much depending on wind conditions, and it assumes that the aircraft will not manoeuvre to avoid obstacles.

78. The disagreement as to the need to be able to achieve a 50 foot screen height is one of the key issues in dispute between the experts. There are other disagreements between them, some of which are not matters for the experts, such as what should be made of the facts that the flying school has placed restrictions on its activities and that the airfield operators have not put more restrictions on flying. They also disagree as to the application of CAP 793 to this airfield, but not on an issue relevant to the issues in this case. In any event, the CAP does not provide that obstacles of less than 150ft within 2000m of the runway are immaterial to the safe operation of the airfield. Capt. Kingswood accepts that an obstacle of 150 feet on the arrival track to Eshott would be an issue. They also comment in different ways upon the threshold crossing clearances for aerodromes equipped with glideslope visual lighting aids, which Eshott is not. They agree that for the certification of these aids the target height for airfields receiving light piston powered aircraft is 20 feet wheel clearance at the runway threshold with a minimum height requirement of 5 feet.

79. Both provided their opinions on whether the passage of aircraft they were shown on film, and those observed by Capt. Kingswood at his visit to the site, evidenced whether or not the aircraft were taking-off and landing in a stable or normal manner. Mr Fairbank thought not and Capt. Kingwood was of the view that they were, but this was highly anecdotal, depending on the pilot and the weather conditions and aircraft on view. Save for film of a landing on runway 01, it was difficult to relate the unsafe features of the landing described by Mr Fairbank to what could be seen on film. Nevertheless, there was the evidence of Mr Wright as to his filmed landing which he had said was steeper than it ought to have been due to the trees. There was also the landing on runway 01 on which a Cessna could be seen to come in quite steeply, over flare and touch down beyond the south side of the trees at Merlin Wood, thus overshooting the first third of the runway, which is where touch down should occur. Capt. Kingswood said he did not have a lot of concerns about this landing as he could not see where the touch-down was and he was dubious of the camera angle.

80. I did not detect a problem with the camera angle and the reason the touch- down was not visible was because the aircraft had passed beyond the start of Merlin Wood, i.e. over a third of the way down the runway, whilst still airborne. Mr Fairbank described what he had seen as an example of an unstable approach, where a pilot who has come in over the trees, dived for the runway, reducing power but increasing airspeed, thus leaving less time to assess the landing flare. On this piece of evidence, I preferred the opinion of Mr Fairbank as his description accorded with what I could see, but recognise I have to be careful not to lay too much weight on such a limited sample of landings.

81. The issue of turbulence was only touched upon by the experts and is not mentioned in their joint statement at all. Mr Woodgate said in his statement that he had experienced turbulence and wind shear due to the trees at the ends of runways 26 and 19. Mr Wright said these trees generate turbulence and wind- shear, though he did not give evidence as to an occasion when this had affected his flight. In cross-examination Mr Pike said that wind from the trees to the side of runway 01changes the airflow and requires a huge correction.

82. Capt.Kingswood was cross-examined about the presence of turbulence, wind shear and their effect. He said that trees around the runway can produce turbulence depending on wind speed and aircraft were particularly vulnerable when taking-off and landing as they were travelling at slow speed. Wind shear occurs when the wind changes in direction and speed. This is a predictable event and when it occurs it is not a day for flying light aircraft. He did not attribute wind shear to the presence of trees.

83. Capt. Kingswood accepted that the trees at Merlin Wood could cause turbulence on the downwind side of the wood which would be variable. His report indicated that many airfields have large buildings such as hangers which produce turbulence and he identified 9 airfields whose entries in Pooley’s Guide warn pilots of potential turbulence due to the presence of trees. These are matters which pilots are expected to take into account in the management of their aircraft. He accepted that there could also be turbulence down wind of the trees at the ends of the runways but said that the pilot will allow for this when considering take-off performance.

The parties’ contentions

84. Mr Latimer points to the evidence of 5 witnesses, all pilots, who speak of the difficulties they have experienced due to the trees, and says that their evidence is supported by Mr Fairbanks. Capt. Kingswood is in the minority in the view he expresses, but even he accepted that the trees would interfere with take-off and landing to some extent, albeit he said that it was manageable. He argues that the difficulties caused by the trees is substantial both because there is evidence of the damaging impact they have had on safety and because it is not unreasonable for the claimant to insist on the use of the full extent of the airspace it enjoyed before encroachment by the trees, as it enables pilots to achieve a stable landing more easily and gives them fewer complicating factors to take into account on take-off.

85. Miss Jarron argues that the difficulties suggested by Mr Latimer are overstated. I should reject the evidence of Mr Pike and Mr Woodgate, as they are partial and unreliable witnesses in any event. Mr Parkinson is prone to exaggeration, as is apparent from his letter to Mr Muir concerning the termination of the licence in which he said that it would prevent him from using his plane at Eshott, yet there he remains. Mr Slater said he could land steeply due to the characteristics of his aircraft and Mr Wright accepted he was able to achieve a safe landing. Mr Fairbank accepted, in an addendum report, that if the trees were substantially shorter than 30 feet this would have the effect of reducing the immediate influence of the trees somewhat, which Miss Jarron claims is a concession which reduces the influence of the trees from a substantial interference to one which should be acceptable. She says that the height of the trees cannot interfere with the passage of aircraft as they should be passing the screen height of 50 feet, both on take-off and landing. Finally, there is her point about the obligations of a servient owner being merely passive. The trees doing what they do naturally, i.e. growing into the airspace is not something which the defendants are required to remedy, thus it cannot amount to an interference with the easement by them.

Discussion and Conclusion

86. My starting point is that at the time of the grant users of the airfield could overfly the defendants’ land as low as they chose provided that maintained a safe height. I accept that pilots are required to ensure that they have sufficient runway to take-off and land. The argument as to whether or not the pilot is required to perform an AIC 127/2006 calculation is a red herring, for in the joint statement both experts accepted that use of the factors in this document are recommended and generally used as best practice. The 50 feet screen height figure is taken from the AIC. In response to my questions, Mr Fairbank suggested that the applicable guidance was no longer in this document but in the Skyway Code, which makes no reference to the 50 feet figure. He did not produce a copy of the Code and he did not refer to it in the joint statement when dealing with the significance of the AIC. Capt. Kingswood said AIC/127/2006 is still current and on the AIC website and is different from the Skyway Code. I prefer Capt. Kingswood’s evidence on the point in view of his consistency on this issue together with the absence of any reason being provided as to why this safety factor, which is accepted as best practice, has been withdrawn. That said, however, whilst the AIC calculation provides comfort as to the adequacy of the runway length for the aircraft in the conditions prevailing on the day, it does not regulate or prohibit an aircraft landing or taking-off at a lower screen height provided that is safe. The runway length requirements produced by the calculation will be good up to a 50ft screen height.

87. The key question to ask, therefore, is as to what is the minimum flying altitude upon which the clamant can reasonably insist? Much of Capt. Kingswood’s evidence was directed at demonstrating that the claimant should be able to overcome the effect of the trees by steeper descent and ascent and adjusting for the presence of turbulence. These are factors relevant to a different question, namely, whether the use of the airspace sought by the claimant is reasonably necessary.

88. The fact that the experts agree that aircraft approach angles steeper than 3° can be managed and are acceptable in general aviation does not mean that the claimant is unreasonable in insisting upon use of sufficient airspace to achieve that angle, or one close to it, provided that pilots are able to keep to a safe height over the defendants’ land during the descent. There is a good reason why pilots would wish to be able to land at a shallow constant angle as this promotes stable flight. I accept the logic of Mr Fairbank’s evidence that it is more difficult to judge the point at which to flare the aircraft and to control landing speed and position at steeper descents because the aircraft naturally picks up speed as it descends, which is contrary to what the pilot is trying to achieve, and can lead to the aircraft being caused to float above the runway for a distance instead of touching down, as appeared to be the case of the landing on runway 01 upon which both experts commented. It is not unreasonable to insist upon having the option to land in as stable a manner as is available.

89. Similar considerations apply to take-off, where the fewer obstacles in the path of the aircraft the less there is for which the pilot needs to make adjustments. The same can be said about the reduction in turbulence at the ends of runways 01 and 26.

90. There is evidence from the claimant’s witnesses, which I accept, that the trees are forcing aircraft into steeper approaches than the pilots would wish and present a hazard. Mr Wright, Mr Slater and Mr Parkinson all struck me as reliable witnesses. The fact that Mr Parkinson was prepared to engage in what may have been hyperbole in an attempt to persuade Mr Muir to relent does not cause me to doubt that conclusion. Their evidence accorded with the description of how a pilot goes about achieving a landing, which itself is consistent with the CAA approved training manuals exhibited to Mr Pike’s third statement and is consistent with the video of Mr Wright’s landing and that of the aircraft on runway 01 commented on by the experts. There was some evidence to the contrary from Mr Coppin, but it seemed to me that his experience was largely with microlights, which generally have short take-off and landing capabilities, according to Capt. Kingswood, and he did appear to want to argue the case. In any event, he is not in a position to say that the claimant’s witnesses did not experience difficulties due to the trees, and I prefer their evidence on the subject.

91. As to take-off, there is evidence from the claimant’s witnesses Parkinson and Wright, that they limit the amount of fuel and number of passengers to ensure that they can clear the trees on runway 26. Mr Parkinson has a similar problem on runway 19 and Mr Wright is concerned by the effect of turbulence at the south end of runway 19, on take- off and landing. Whilst I have expressed reservations about the reliability of the evidence of the two directors of the claimant, Mr Woodgate’s evidence concerning the presence of turbulence at the end of runway 26 is credible as it is supported by Mr Parkinson and Mr Wright and is consistent with Capt. Kingswood’s acceptance that the trees may be the cause. I accept this evidence.