Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

England and Wales High Court (Chancery Division) Decisions

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> England and Wales High Court (Chancery Division) Decisions >> Broomhead v National Westminster Bank Plc & Anor [2020] EWHC 1005 (Ch) (01 May 2020)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Ch/2020/1005.html

Cite as: [2020] EWHC 1005 (Ch)

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

BUSINESS AND PROPERTY COURTS

OF ENGLAND AND WALES

BUSINESS LIST (ChD)

London EC4A 1NL |

||

B e f o r e :

____________________

| JONATHAN MARK BROOMHEAD |

Claimant |

|

| - and - |

||

| (1) NATIONAL WESTMINSTER BANK PLC (2) THE ROYAL BANK OF SCOTLAND PLC |

Defendants |

____________________

Charlotte Eborall (instructed by Addleshaw Goddard LLP) for the Defendants

Hearing date: 28 February 2020

____________________

Crown Copyright ©

- On 21 June 2018 in claim number B30 LS335, which was between the same parties as this claim, His Honour Judge Klein handed down a judgment that dismissed the claimant's claim against the defendant banks ("the first claim"). The judgment followed a trial that lasted seven days during which the trial judge heard evidence from the claimant and eleven further witnesses (five for the claimant and six for the bank), four further statements were read and experts gave evidence for the claimant and the defendants. The claimant was represented at the trial by leading counsel and two juniors, one of whom settled the particulars of claim, in this claim ("the new claim"). The judgment runs to 85 pages and 374 paragraphs and contains a very detailed analysis of the evidence.

- The first claim concerned the claimant's business banking relationship with the first defendant. The claimant traded as JMB Holdings and operated a loan account and a current account. He also operated through a number of companies including JMB Hire Ltd and JMB 100 Ltd. His case was that by 2009, either as a sole trader, or through one of these companies, he was ready to become a major hirer of heavy plant and machinery mainly in the market around Derbyshire. The claimant alleges that by virtue of a series of promises made by the first defendant, he had the benefit of an oral collateral contract that gave him an entitlement to continued banking support. As a consequence, he said, when his accounts came under the control of the second defendant's Global Restructuring Group ("GRG") and the support was withdrawn, the first defendant was liable to him for breach of the collateral contract. He claimed damages of £13.78 million.

- The claimant also put his case in the first claim in two further ways. First, that the contracts he entered into with the bank were subject to certain implied terms that the first defendant breached. Secondly, he sought financial compensation under section 140B of the Consumer Credit Act 1974 on the basis that his banking relationship with the first defendant was unfair.

- Although the claimant had dealings with the second defendant when his borrowing was referred to the GRG, it was common ground for the purposes of the first claim that the first defendant was liable for any actionable wrong of the GRG and it was proper to dismiss the claim against the second defendant.

- On 13 December 2018, Newey LJ dismissed the claimant's application for permission to appeal.

- The claimant was ordered to pay the defendants' costs of the first claim and ordered to make a payment on account of £871,157.60. After nothing was paid, the first defendant served a statutory demand and thereafter a bankruptcy petition was issued on 19 June 2019. The new claim was issued on 23 July 2019 and amended on 29 August 2019. Particulars of claim were served on 12 September 2019. On 6 November 2019, District Judge Kelly sitting at the County Court at Birmingham stayed the petition pending the determination of the defendants' application to strike out or for judgment in the new claim.

- In the new claim, the claimant seeks an order rescinding or setting aside His Honour Judge Klein's judgment dated 21 June 2018. Although nothing turns on it, strictly the claim must be directed to the order made by the judge on that occasion, rather than his reasoned judgment because it was the order that implemented the conclusions set out in the judgment. The claimant alleges that " by reason of post-trial discoveries and revelations he can show by [the new claim] that the Defendants were guilty of conscious dishonesty in the presentation and pursuit of the Defence [in the first claim]". In short, he says judgment in the first claim was obtained by the defendants' fraud. The substance of the claimant's case is contained in paragraph 11 of the draft amended particulars of claim which has 26 sub-paragraphs providing particulars of his case. It need hardly be said that the claimant's allegations are of the utmost gravity.

- This judgment follows the hearing of three applications on 28 February 2020:

- The first and second applications stand or fall together. If the claimant's case, as it is put forward in the draft amended particulars of claim, is not capable of surviving the test for striking out and/or the test for summary judgment then, subject to one further point, permission to amend will be refused. The additional point is one raised by Mr Roe QC, who appeared for the claimant, and concerns the principle that where a statement of case is found to be defective, the court should consider whether that defect might be cured by (in this case) further amendment and, if it might be, the court should refrain from striking it out without first giving the party concerned an opportunity to amend Soo Kim v Youg [2011] EWHC 1781 (QB). That is a matter to which I will return later in this judgment.

- The third application concerns a witness statement made by Mr Mark Wright on behalf of the claimant served on 25 February 2020, just two days before the hearing. On any view the statement was served very late. A timetable for serving evidence was provided in the order made on 3 December 2019. The order was made on the hearing of the claimant's successful application to adjourn the hearing of the defendants' application. The parties agreed an adjustment to the timetable and the claimant's evidence in response to the application and the defendants' evidence in reply was served in accordance with it. The defendants were not forewarned about Mr Wright's evidence and, at least in part, objection could have been taken to it on the ground that Mr Wright provides opinion evidence in relation to which permission is needed under CPR 35.4. However, the defendants have chosen to adopt a pragmatic stance. They did not seek an adjournment and accepted that the evidence could be admitted. Ms Eborall, who appeared for the defendants, submitted that, when considered carefully, Mr Wright's evidence does not assist the claimant.

- In these circumstances, there is no purpose in considering whether the order dated 3 December 2019, as varied, contained an implied sanction, or applying slavishly the three-stage test derived from Denton. I will make an order permitting the claimant to rely on Mr Wright's statement albeit that the court is entitled to consider any shortcomings in Mr Wright's ability to provide expert evidence.

- I should add that at the end of the hearing Mr Roe QC was requested by the court to provide a summary of the page references for the documents upon which he had paid emphasis during his submissions. The document that was lodged by him and Mr Budworth contained a new submission in support of the claimant's case. Naturally Ms Eborall took issue with that approach and I have had regard to her response to it.

- The tests for striking out a claim and for summary judgment are not in doubt. Where it is said the statement of case discloses no reasonable grounds under CPR 3.4(2)(a), the court must decide whether the claim, or the defence, is bound to fail. Even if the court reaches that conclusion, if the claim is made in a developing area of law, the court may conclude that the merits needs to be assessed by reference to the evidence as it is found to be at the trial of the claim: Hughes v Colin Richards & Co [2004] PNLR 35 (CA).

- Where CPR 3.3(2)(b) is relied upon the court must be satisfied that there is abuse and the striking out is warranted applying the provisions of the overriding objective. An attempt to re-litigate issues which were raised, or ought to have been raised in previous proceedings, may constitute an abuse of the court's process but whether there is abuse involves the court looking at all the circumstances and applying a broad merits-based approach, taking account of all the public and private interests involved: Henderson v Henderson (1843) 3 Hare 100 and Johnson v Gore Wood & Co (No1) [2002] AC 1 at [31] per Lord Bingham.

- In Dexter Ltd v Vlieland-Boddy [2003] EWCA Civ 14 at [49] Clarke LJ summarised the principles to be derived from Johnson v Gore Wood & Co, a summary that was cited with approval by the Court of Appeal in Aldi Stores Ltd v WSP Group plc [2008] 1 WLR 748.

- Under CPR 24.2 the court may grant summary judgment if the respondent has no real prospect of succeeding on the claim or defending the claim and there is no other compelling reason why the case should be disposed of at a trial. The applicable principles are helpfully summarised in the judgment of Lewison J in Easyair Ltd v Opal Telecom [2009] EWHC 339 (Ch) at [15] and subsequently approved by the Court of Appeal. It is unnecessary to set out these well-known principles in this judgment.

- Care needs to be taken to avoid conflating an application that is made under both CPR 3.4(2)(a) and CPR 24.2. In the case of the former, the primary focus is on the statement of case. The application of the tests under CPR 24.2 involves wider considerations and the court may have regard to the evidence the respondent produces, and is reasonably likely to be able to produce, always bearing in mind the strictures to avoid conducting a mini-trial.

- The importance of pleading properly is well known and has been discussed in numerous authorities. One of the best known examples is the speech of Lord Millett in Three Rivers District Council v Bank of England [2001] UKHL 16 at [184] to [186] and [189]. I will not over burden this judgment by citing the passage. It is however helpful to refer to a passage in the judgment of Flaux J (as he then was) in JSC Bank of Moscow v Kekhman and others [2015] EWHC 3073 (Comm) at [20] after he has considered the speeches of Lords Hope, Hobhouse and Millett in Three Rivers and the submissions about them made by leading counsel:

- The heading above contains two well known extracts from the judgment of Lord Bingham in HIH Casualty and General Insurance Ltd v Chase Manhattan Bank [2003] 1 All ER (Comm) 349 at [15]. The circumstances in which fraud will unravel a judgment in a prior claim and lead to it being set aside was recently considered by a seven judge court in the Supreme Court in Takhar v Gracefield Developments Ltd and others [2019] UKSC 13. In that case, the claimant had not alleged fraud in the original claim. In her second claim she relied on evidence that had not been available to her in the original claim. The defendants alleged that with reasonable diligence she could have obtained the further evidence before the trial of the original claim with the consequence, they submitted, that she was not entitled to apply to set aside the judgment. The Supreme Court considered the principles upon which a court may set aside a judgment obtained by fraud. Lord Kerr gave a judgment with which Lords Hodge, Lloyd-Jones and Kitchin agreed. They also agreed with the judgment of Lord Sumption, who agreed with Lord Kerr, about the relevant principles. The test that is to be applied by the court in a claim seeking to set aside an earlier judgment for fraud is not disputed by the parties in this claim and the overwhelming preponderance of view[1] in the Supreme Court in Takhar was that the relevant principles are those summarised by Aikens LJ in Royal Bank of Scotland plc v Highland Financial Partners LP [2013] 1 CLC 596 at [106]:

- The issue of 'materiality' is an important one when considering the effect of fraud on a judgment. There is a tension between the principle that 'fraud unravels all' and the equally important principle of finality in litigation. It cannot be right that dishonesty in the course of a trial that has no effect at all on the outcome can be a basis for the judgment being set aside. There is however a line of authority that a lower test than the test in RBS v Highland Partners should be applied.

- There is a very helpful discussion of the authorities on this point in the judgment of Master Bowles in Davies and others v Morris [2018] EWHC 1901 (Ch) at [25] to [44], albeit that his decision only had the benefit of the decision of the Court of Appeal in Takhar. Master Bowles points to the decisions of the Court of Appeal in Hamilton v Al Fayed [2000] EWCA Civ 3012 and Salekipour v Parmar [2017] EWCA Civ 2141. He refers to the passage in the judgment of Lord Phillips at [26] in Hamilton where he says:

- In his judgment in Salekipour v Parmar, the Master of the Rolls at [88] [93] considered the test for materiality suggested by Lord Phillips in Hamilton and the test set out by Aikens LJ in Royal Bank of Scotland v Highland Financial Partners. He points out that the formulation in the latter case was one agreed between counsel, rather than being one produced by the court, and that Hamilton was not cited. Sir Terence Etherton MR at [93] said:

- Neither Salekipour nor Hamilton were referred to in the judgments of the Supreme Court in Takhar or cited in argument. That may well be because the question of materiality was not directly in issue in the claim. However, the Highland test adumbrated by Aikens LJ was unequivocally approved. Even though the issue before the Supreme Court was a relatively narrow one, I do not consider it is realistically open to the claimant to contend that the test is in doubt and I proceed on the basis that although the approach of Lord Phillips in Hamilton was not considered in Takhar, the Highland test should be taken as representing the law following its express endorsement by five members of the Supreme Court and its indirect approval by the two dissenting members of the court as well.

- Mr Roe QC sought assistance from the judgments of Lord Briggs and Lady Arden (particularly paragraph [105]) concerning the availability of summary judgment where a party seeks to set aside a judgment that is alleged to be based on fraud. I can see nothing in either judgment that suggests reverse summary judgment is not available, or is more difficult than usual to obtain, in such a case. The test remains that set out in CPR 24.2 as it has been interpreted and applied over the past 20 years.

- The first defendant provided loan and overdraft facilities to the claimant from 2002. His borrowing increased over a period of years to £800,000 with £400,000 borrowed on a secured loan and the balance on his overdraft facility. The claimant relies on three promises that he says were made to him that led to the Collateral Contract:

- At paragraphs 85 to 97 of his judgment, HHJ Klein described a number of documents that were created and amended by the first defendant in the period following these promises. Later, the first defendant extended the date until which the overdraft facility would continue until 11 April 2009 and in relation to the loan agreement a supplemental dated 18 March 2009 was produced by the first defendant that extended the repayment date for the loan until 11 April 2009. However, this agreement was not signed by the claimant and without it the loan was due for repayment on 28 February 2009.

- It is right to mention that the judge's approach to the recollections of witnesses took account of the approach discussed by Leggatt J (as he then was) in Gestmin SGPS SA v Credit Suisse (UK) Ltd [2013] EWHC 3560 (Comm) at [15]-[22]. Unsurprisingly, in a case that concerned oral statements said to have been made at meetings held 14 years previously, the judge placed heavy reliance on contemporaneous documents. If the claimant is right that there is a plausible basis for alleging the deliberate manipulation of documents, or that adverse documents were knowingly withheld on disclosure, the views the judge came to about the witnesses of fact may well need to be reviewed.

- Between 2006 and 2009, the claimant used JMB 100 Ltd to enter into hire purchase agreements with third party lenders, JMB Hire Ltd to invoice for work done and JMB 101 Ltd to pay staff. JMB Hire Ltd entered into an invoice discounting agreement with RBS Invoice Finance Ltd and he was able use the funds released by the discounting facility to pay deposits for plant and machinery bought using hire-purchase.

- The claimant alleged that he was effectively compelled to advertise and sell his plant and machinery from March 2009 because he was told by Mr Mosley that the bank did not intend to extend the period of the loan agreement or the overdraft repayment date.

- The claimant's case failed in every respect. In summary the judge found:

- The defendants' application is supported by a witness statement from Benjamin Lowans who is a partner with Addleshaw Goddard LLP. His first witness statement is largely formal and sets out the basis upon which the application is made in a helpful way. The claimant served a witness statement to which Mr Lowans has responded and the claimant has in addition the benefit of the lengthy witness statement from Mr Wright.

- The court is asked to review the process of disclosure in the first claim based on evidence that is partial and unsatisfactory. I highlight two points in particular:

- I propose therefore to consider first the new claim as it is pleaded. If it meets the minimum requirements for a statement of case that alleges fraud, I will go on to consider whether it meets both limbs of the Part 24.2 test and whether the claimant should be offered a further opportunity to plead his case in light of the evidence he has obtained from Mr Wright.

- The claimant makes a number of complaints about the process of disclosure in the first claim. An order for standard disclosure was made on 24 April 2017 and the defendants' first disclosure statement was served on 11 August 2017. It was signed by Hannah Summerfield, in-house counsel for the defendants. Mr Roe QC made it clear at the hearing that allegations of dishonesty relating to the defendants' disclosure are not directed to her. It is apparent from the disclosure statement she signed that the disclosure exercise carried out by the defendants was not a straightforward exercise. The lengthy period covered by the relevant events and the period of time that had passed before the first claim was issued go some way to explain this.

- The disclosure statement records that: "The search parameters of the Bank [sic] disclosure exercise have been set out in correspondence with the Claimant's solicitors." The correspondence has not been exhibited. There is no indication that an Electronic Disclosure Questionnaire (EDQ) was completed, or that the absence of one was a matter of complaint. The clear impression given by the documents exhibited by the claimant is that the scope of disclosure was agreed between the parties. Had the defendants been required to complete an EDQ they would have been required to identify all databases of electronic documents and would have been obliged to reveal the existence of a database named E-Flex. However, it is not open to the defendants to rely on a lack of due diligence, if that could be alleged.

- Under the heading "Custodians and Date Ranges", the disclosure statement identifies four custodians, including Mr Mosley, and says that in his case the date range for searches was "April, May and June 2004 and 1 April 2008 31 December 2008". The absence of March is apparent. In the section of the statement that deals with "Searches and Email Data" an explanation about the storage of back-up tapes with Iron Mountain is given. The statement goes on to say: " the Bank has attempted to restore back-up tapes containing the emails belonging to Mr Mosley for the period April, May and June 2004. Whilst Iron Mountain was able to identify the relevant back-up tapes for Mr Mosley for the period April and June 2004, no back-up tapes were located for May 2004."

- Paragraphs 11 to 13 of the disclosure statement explain the nature of the Relationship Management Platform ("RMP") which was one of the main sources of data, and how it works.

- Two further disclosure statements were provided with additional disclosure on 15 November 2017 and 13 March 2018. In the first additional disclosure statement the defendants say they have recently located a further hard copy recoveries file with the result that a number of documents were inadvertently omitted from the original list of documents. In the final statement the defendants say they recently located further bank statements, transaction history sheets and credit papers. The trial opened on 30 April 2018 some six weeks after the final tranche of disclosure was provided.

- There is nothing in the process of giving disclosure by the defendants that of itself provides evidence of a fraudulent purpose or approach. I also make the following observations:

- The substance of the claimant's case is contained in paragraphs 7 and 11 of the draft amended particulars of claim. They can be found in an appendix to this judgment. Paragraph 11 runs to more than 11 pages and has 26 sub-paragraphs.

- Paragraph 7 of the draft amended particulars of claim refers to the disclosure provided by the defendants a few weeks before the trial of the first claim and refers to information provided to the claimant by a whistle-blower who is not identified. The person in question is Mr Mark Wright whose witness statement was served shortly before the hearing of the defendants' application before me. In the course of his submissions, Mr Roe QC suggested that paragraph 7 of the draft amended particulars of claim should really be a particular or particulars forming part of paragraph 11. It is, however, convenient to deal with it as it appears in the draft pleading because that is the claimant's case he wishes to put forward in response to the defendants' application.

- It suffices to observe that:

- Paragraph 11 of the draft amended particulars of claim asserts that the defendants were guilty of "conscious dishonesty in the presentation and pursuit of the Defence" and makes bare assertions about the effect of the dishonesty on the judgment without giving any particulars of causation. I will comment upon each of the sub-paragraphs in turn.

- When dealing with the defendants' application to strike out the claim, I will adopt the following approach. I will consider:

- When considering the first of the three stages set out above, I have to consider whether the claimant has pleaded facts that justify a plea of fraud. The claimant's case will necessarily involve considering whether the court is able to infer from the primary facts that are relied on by the claimant that the defendants possessed the relevant state of mind and acted on it.

- As an initial observation about paragraph 11 of the draft amended particulars of claim, it is pleaded in a way that serves to mask rather than to reveal the claimant's case. There are many sub-paragraphs, indeed the majority, that do not further the allegation of conscious and deliberate dishonesty. It does not help the claimant to:

- The more promising particulars from the claimant's perspective are those at (1), the scrape by a find and replace facility, (13) the blank spaces in the RMP (14) documents that do not follow on naturally, (15) the broken thick perimeter lines, (20) the missing back-up tape.

- However, whether the highpoints of paragraph 11 of the draft amended particulars of claim are looked at in isolation or together, they fall a long way short of pleading a case of conscious and deliberate dishonesty that was material. The particulars do not justify a plea of fraud because they do not provide a plausible assertion of dishonesty and do not support a necessary inference of dishonesty, whether they are taken together or looked at separately. Furthermore, and importantly, materiality is merely asserted but is wholly unparticularised.

- In paragraph 7.2 of the draft amended particulars of claim, the claimant says that the defendants failed to reveal the existence of the E-Flex record keeping system. It is not alleged, however, that the defendants were under an obligation to reveal every source of documents or that there were material failings in the manner in which disclosure was given. The pleading does not address the obligations placed on the defendants by CPR 31 and Practice Directions 31A and 31B, whether they were breached and whether such a breach, if there were one, is evidence of dishonesty or was material.

- Is there a reason why the court should not strike out the claim even though I have concluded it is bound to fail? Hughes v Colin Richards & Co [2004] PNLR 35 (CA) is an example of a case which was permitted to go to trial. However, the circumstances there were very different to this case. It concerned the scope of the duty owed by an accountant who was instructed to set up a trust. At the time there was uncertainty about whether a duty was owed to the settlor, or to the beneficiary, or both and the Court of Appeal considered that the judge at first instance had been right to refuse to strike out the claims because the existence of a duty, or otherwise, was best determined against the facts as they were found at a trial. In this case, in light of the decision in the Supreme Court in Takhar, the applicable test can be taken as that set out in RBS v Highland Partners. Furthermore, even if the lower materiality test derived from Hamilton v Al Fayed were to be applied, the claimant would not have made out a pleaded case on materiality.

- At the hearing, Mr Roe QC focussed his submissions on two principal areas, the missing back-up tape and the failure to reveal the E-Flex system. He also highlighted important aspects of the evidence provided by Mr Wright. He is now the managing director of a company that, as he describes the business, "specialises in supporting and helping vulnerable whistle-blowers wishing to make disclosures regarding behaviour within the financial sector, mainly in relation to banks." He says he was employed over 25 years in a number of different positions in banks between June 1988 and July 2013. He worked for the second defendant in his last role as a Senior Financial Planning Manager and is familiar with both the RMP and E-Flex systems, how they operate, and the nature and appearance of documents produced on them. His statement provides cogent evidence about a number of matters that are directly material to the case the claimant wishes to put forward. The defendants are correct to point out that in his conclusion, Mr Wright says only that: "the Court may have been misled by the Defendants." Nevertheless, there are aspects of his evidence that are troubling.

- I will refer to some of its principal features.

- On an application to strike out a claim, the court assumes the facts pleaded are true and I have determined that the claimant has not pleaded a case, even in his draft amended claim, that has any prospect of success. However, it seems to me that in light of Mr Wright's evidence, the claimant should have the opportunity, if he wishes, to replead his case. This will involve the court making an order striking out the particulars of claim (but not the claim) and refusing the claimant's application for permission to amend. A period will be set for the claimant to provide to the defendants in the first instance draft particulars of claim. If they do not accept that a viable claim is pleaded, the claimant may restore the hearing and seek the court's permission to serve the draft he has provided. The onus will be on him to show that it is a claim which is not bound to fail.

- I emphasise that in making this order I am not encouraging the claimant to replead his claim or suggesting that based upon the evidence he has provided and the submissions put forward on his behalf he will be able to plead a viable claim of conscious dishonesty that was material to the outcome of the first claim. I will hear counsel about whether the court should impose any preconditions before the claimant is permitted to produce a revised claim.

- I turn to the defendants' application for summary judgment. I observe that:

- At present it is unclear whether the claimant is able to plead a viable claim. I have determined that he should be given an opportunity to replead the claim having regard to Mr Wright's evidence. In those circumstances I cannot be satisfied that the claimant has no real prospect of success. The application for summary judgment will be adjourned to be dealt with at a later date if the circumstances make that necessary.

- In view of the Covid-19 lock down, this judgment will be handed down at a remote hearing conducted via Skype. If the parties' counsel are not available on the date selected by the court, the judgment will be handed down in the absence of the parties, and all consequential issues, including any application for permission to appeal, will be adjourned to a later date.

Chief Master Marsh:

The new claim

(1) The defendants' application to strike out the claim, and/or for summary judgment, issued on 14 October 2019.

(2) The claimant's application for permission to amend his particulars of claim issued on 24 January 2020.

(3) The claimant's application for permission to rely on further evidence served on 25 February 2020.

Pleading fraud or dishonesty

"The claimant does not have to plead primary facts which are only consistent with dishonesty. The correct test is whether or not, on the basis of the primary facts pleaded, an inference of dishonesty is more likely than one of innocence or negligence. As Lord Millett put it, there must be some fact "which tilts the balance and justifies an inference of dishonesty". At the interlocutory stage, when the court is considering whether a plea of fraud is a proper one and whether to strike it out, the court is not concerned with whether the evidence at trial will or will not establish fraud but only with whether the facts are pleaded which would justify the plea of fraud. If the plea is justified, then the court must go forward to trial and assessment of whether the evidence justifies the inference is a matter for the trial judge. This is made absolutely clear in the passage from Lord Hope's speech at [55]-[56] which I quoted above."

Fraud " is a thing apart;" and " fraud unravels all ".

"The principles are, briefly: first, there has to be a 'conscious and deliberate dishonesty' in relation to the relevant evidence given, or action taken, statement made or matter concealed, which is relevant to the judgment now sought to be impugned. Secondly, the relevant evidence, action, statement or concealment (performed with conscious dishonesty) must be material. 'Material' means that the fresh evidence that is adduced after the first judgment has been given is such that it demonstrates that the previous relevant evidence, action, statement or concealment was an operative cause of the court's decision to give judgment in the way it did. Put another way, it must be shown that the fresh evidence would have entirely changed the way in which the first court approached and came to its decision. Thus, the relevant conscious and deliberate dishonesty must be causative of the impugned judgment being obtained in the terms it was. Thirdly, the question of materiality of the fresh evidence is to be assessed by reference to its impact on the evidence supporting the original decision, not by reference to its impact on what decision might have been made if the claim were to be retried on honest evidence." [emphasis added]

"A new trial should be ordered when the interests of justice so demand. Where a party has behaved fraudulently, been guilty of procedural impropriety or some other irregularity has affected the fairness of the trial the vital question to be asked is whether there is a real danger that this has influenced the outcome. If there is, a retrial should normally be ordered. If there is not, the interests of justice require that the decision should stand."

"I am inclined to agree with Mr Davies that the test was over-stated in Royal Bank of Scotland and that the proper approach is that laid down by the Court of Appeal in Hamilton."

The first claim

(1) At a meeting between the claimant and Mr Mosley of the first defendant on 22 March 2004 it is alleged two promises were made: that the bank would grant the claimant a loan for a term of 20 years (the first promise") and that provided interest and capital repayments were met and the overdraft facility was not exceeded the overdraft facility would be "renewed automatically" and repayment would not be demanded during the term of the loan ("the second promise").

(2) At the second 21 May 2004 meeting, Mr Mosley gave the claimant a loan agreement for signature. It offered him a £400,000 secured interest-only loan to be repaid in full on 30 June 2006. The claimant says that at the meeting, despite the express terms of the agreement, Mr Mosley said the loan agreement would be "automatically renewed" provided the interest payments were made and the overdraft facility was not exceeded ("the third promise").

(1) He was unable to accept the claimant's evidence. He found it to be to a large degree a reconstruction of events and that he was unable to be a dispassionate witness " instead seeking to present his case in what he thought was its best light; " and that was largely due to an unshakeable conviction that the failure of his business was due to the first defendant's conduct. [229]

"I approach Mr Broomhead's evidence with caution and have concluded that, before attaching significant weight to it, I should carefully test it against the contemporaneous documents and the inherent probabilities.": [246].

(2) The evidence of the claimants' witnesses was of limited assistance to him. There were no witnesses with first-hand knowledge of the meetings at which the three promises relied on by the claimant were said to have been made: [247] to [252].

(3) The evidence given by the three principal witnesses for the first defendant, Mr Derbyshire, Mr Pearson, and Mr Mosley, was given fairly and they freely acknowledged that their recollection of events was "at best" limited. Mr Brown was a "fair witness". The judge was less impressed by the evidence given by Mr Harvey: [253] to [255].

(4) The first defendant's case that the Promises were not made was much stronger than the claimant's contrary case: [268]. In the course of reaching that conclusion, the judge discussed in paragraph [263] the first defendant's internal records that showed for a significant period the term of the loan was 16 years. The judge accepted Mr Mosley's explanation for how this came about. In fact, the claimant's case, as it was pleaded, was based on an agreement by the first defendant for a 20 year loan. After disclosure the claim was adapted to fit the first defendant's internal documents. The claimant's evidence on this key point, with the benefit of disclosure is far from being unequivocal. He said in this statement:

"When I signed my Particulars of Claim I thought that I had been promised a 20 year term But the documents appear to me to show that Mr Mosley promised me 16 years (or, possibly, 15 years), and that I must have indicated that was sufficient."

(5) If the Promises were made, they were not intended to have contractual effect: [284].

(6) The applicable limitation period was 6 years under section 5 of the Limitation Act 1980 and the period expired long before the claim was issued: [292].

(7) By early 2009, the claimant's businesses were not generating sufficient income to meet the hire purchase payments and it was for that reason it was advertised for sale. Thus, the claimant's case on causation failed: [339].

(8) The claimant's loss of a chance claim failed: [352].

(9) There was no merit in the claim under the Consumer Credit Act 1974 and the relationship was not unfair: [371].

Evidence on the applications

(1) Mr Lowans' second statement contains evidence that is largely outside his own knowledge. However, where he is required to provide the source of his evidence, he says he is "informed by the Bank". He states in paragraph 1 that he uses the term "the Bank" to mean both defendants. He therefore appears to be saying that he is informed by both corporate entities of each relevant fact. This seems inherently unlikely. But more fundamentally, stating that the source of evidence is a named corporate party does not comply with the requirements of Practice Direction 32 paragraph 18.2(2): see Punjab National Bank (International) Ltd v Techtrek India Ltd [2020] EWHC 539 (Ch) at [15] [20]. In a case such as this in which the claimant makes serious allegations of dishonesty it is understandable that the solicitors acting for the defendants wish to shield those who provide information from making statements on an application for summary judgment. However, the corollary is that the court may be unable to give more than limited weight to information that is not credited to a source. In large organisations such as the defendants, external lawyers are often instructed by in-house counsel, who in turn obtain information from others. In more routine cases, or in routine applications, the court may be unconcerned about such matters; but in a case such as this, it is really important to know who it is who is attempting to meet the serious allegations the claimant makes. The evidence provided by Mr Lowans has significantly reduced weight as a consequence of a failure to give the sources of his knowledge, particularly when set against some of Mr Wright's evidence that is based upon his own knowledge of the defendants' systems.

(2) The defendants have chosen to permit the court to take account of Mr Wright's evidence. Some of what he says is little more than comment and of no real assistance. However, where he gives evidence from his own knowledge of the way data was captured and treated by the defendants in the material period, or where he expresses an opinion he appears to be qualified to provide, the court is bound to accept it unless it is obviously wrong. To reject his evidence, other than in such an instance, would involve conducting a mini-trial.

Disclosure in the first claim

(1) The fact that the defendants took some time to give disclosure (that is the period allowed for disclosure under the order for directions was longer than is standard) is neutral; taking time over disclosure is equally consistent with the task being undertaken carefully and conscientiously as it is with a fraudulent approach.

(2) The first disclosure statement is full and comprehensive and, it is to be inferred from the lack of challenge, it accorded with the approach to disclosure agreed between the parties.

(3) The provision of subsequent disclosure, which on each occasion was accompanied by an explanation and a further disclosure statement, would tend to demonstrate that the defendants were, as is to be expected, fully aware of their obligation under CPR 31.11. Disclosure is, even when carried out carefully, a complex business and all the more so when the search for documents involves multiple sources dating back over many years. The provision of additional disclosure is not suggestive of fraud.

The new claim

(1) Paragraph 7.1 makes two points. First, based on what the claimant has been told by the whistleblower, the defendants could have provided disclosure in the first claim from the RMP "at the click of a button" and there was no excuse for late disclosure. This overlooks the fact that disclosure involves reviewing the pool of available documents for what can broadly be termed relevance, and also for privilege and business confidentiality. Secondly, it is said that "this alone" (the lack of a reason for late disclosure) suggests that the defendants adopted "a selective approach to disclosure". Neither of these assertions point unequivocally toward dishonesty. Disclosure was provided, albeit on the claimant's case it was late, and disclosure is required to be selective in the sense that a careful review of the available documents is required. It is quite another matter if documents that are known to be adverse are withheld, but that is not alleged.

(2) Paragraph 7.2 refers to the defendants' record keeping system called 'E-Flex' and the failure by the defendants to reveal its existence. However, there is no allegation of dishonesty. There is nothing per se that is dishonest about selecting sources of documents for disclosure unless it could be said, which it is not, that the existence of E-Flex was suppressed because the defendants knew it would reveal documents that were adverse to its case. Mr Roe QC placed considerable reliance on this issue as seen in light of Mr Wright's evidence and its significance requires further analysis.

(3) Paragraph 7.3 says the whistle-blower will provide evidence from his experience of the defendants "deliberately taking advantage of claimants' solicitors' lack of knowledge about the bank's systems for document retention". This allegation, in the way it is put, does not help the claimant as it is unfocussed and furthermore it is not a point Mr Wright deals with in his witness statement.

(1) The claimant alleges that the defendants have manipulated documents from its RMP that were disclosed in the first claim. The claimant says documents show signs of "some form of scrape by a find and replace facility the effect of which was to remove 'unwanted' text and automatically replace it with immediately opposing square brackets ([])". He says this is called a 'wildcard'. He provides an example showing its effect. However, in the example, the wildcard appears only to affect punctuation and there is nothing to suggest that any material text is missing and nothing is said about causation.

(2) The claimant says he does not know whether what he terms "the manipulation" of the defendants' documents was caused by the Section 166 review by the FCA, his claim or both. This adds nothing to his claim.

(3) The allegation here is an example of the diffuse nature of the pleading. It alleges that there are two different versions of handwritten notes made by Mr Brown (a witness for the defendants at the trial) and that the notes are redacted. He suggests that one version "appears to have a post-it note placed over some text. No case on causation is suggested.

(4) Similarly, the claimant relies on two versions of a review document being disclosed, one with and one without a manuscript note visible, and one with some text redacted. The claimant has seen both versions and seen the redacted text. The note itself is not material.

(5) (6) and (7) These sub-paragraphs merely provide narrative about the whistleblower. In (7) the claimant says he "believes that the fingerprints might mark a period in which some manipulation of RMP was achieved." The fingerprint he refers to is the "electronic footprint" left behind every time a document was accessed and altered. However, the point is made at a high level of generality.

(8) The claimant refers to conversations with two former area bank managers. What he reports does not relate to or assist his case.

(9) (10) and (11) make generalised assertions that do not assist the claimant's case and do not assert dishonesty in the defendants' dealings with him.

(12) The claimant says he hold four different versions of some documents but, of itself, that is unsurprising.

(13) and (14) The claimant points out inconsistencies in the layout of unspecified documents without alleging or evidencing dishonesty or causation.

(15) The claimant alleges there are signs of use of a white-out tool and says it is a classic sign of document tampering. But he does not say what information may have been obscured. It appears the document he has in mind dates from 2010 whereas the Promises date from 2004.

(16) This particular repeats particular (3) and adds irrelevant material about RBS' subsidiary West Register.

(17) Various points are made. First, that only some of the documents disclosed included their metadata. This would have been evident prior to the trial of the first claim. Secondly, the claimant refers to a spread sheet created by the GRG. This was a document considered by His Honour Judge Klein.

(18) In this very lengthy particular, the claimant asserts that the loan was renewed internally after the GRG became involved. This issue was dealt with at the trial. He also complains about late disclosure some 5/6 weeks before the trial started of additional documents.

(19) The claimant says that in light of the disclosure of documents by the defendants to Promontory (which was appointed by the FCA to investigate the GRG), the defendants' motivation in delaying disclosure in the first claim "may have been that [they] wished to alter some of the documents or data."

(20) The claimant describes the defendants' failure to locate the back-up tape for May 2004 as "suspicious". He goes on to say that Iron Mountain have a highly effective professional document storage system and that it was likely the defendants would have more than one copy of all back-up tapes "mainly for security purposes, which makes it even more implausible that the bank could not locate this most important back-up tape". Plainly May 2004 was a crucial period for the claimant's case in the first claim given that the Promises he relied on were said to have been made on 22 March and 21 May 2004. It is notable however that the defendants did produce the April and June 2004 back-up tapes.

(21) This is a complaint that the defendants charged too much to restore back-up tapes. The complaint does not forward the claimant's case.

(22) The claimant says the date range for the defendants' disclosure did not include March 2004 and requests were made at the time for disclosure to extend earlier than April 2004.

(23) This is a complaint about the defendants' response the Data Subject Access Requests in April 2019. Clearly it cannot assist the claimant.

(24) It is said that "certain documents" produced under the Data Subject Access Review are different versions of documents disclosed in the first claim.

(25) The claimant refers to an internal advice document created on 2 October 2007. However, the document was dealt with in HHJ Klein's judgment.

(26) The claimant says he has revisited the defendants' disclosure and refers to a sanction sheet signed by Mr Mosley on 25 August 2008. He suggests the date has been overwritten with the date changed to 25/5/04. The case the claimant now makes is not clear and it does not particularise dishonesty.

(1) Whether as it is currently pleaded the draft amended particulars of claim make out a case that is bound to fail. This involves reviewing whether the elements of the cause of action (per Lord Sumption at [60]-[61] in Takhar) are there. The judgment must have been procured by fraud. There must have been conscious and deliberate dishonesty and it must have been material in the way that is explained in RBS v Highland Financial Partnership. The claimant does not have to show that fraud could not have been uncovered with reasonable diligence on his part.

(2) Whether it can be said, if the answer to the first question is in the negative, the court should exercise its discretion to strike out the claim. This involves considering whether the claim is in a growing or uncertain area of law and should be permitted to go to trial.

(3) If the case, as it is currently pleaded, is vulnerable to being struck out, should the claimant have a further opportunity to salvage it to take account of matters raised in Mr Wright's evidence or as a result of a further review of the facts.

(1) note, for example, that the defendants have disclosed differing versions of documents, where they have disclosed an apparently complete version. There could be many innocent, or negligent, reasons why there is more than one version of a document;

(2) say that some elements of the documents were redacted, when redaction is a common feature of disclosure in claims against banks because of the need to protect customer confidentiality;

(3) rely on documents that were considered by the trial judge and dealt with in his lengthy and thorough judgment.

(1) At paragraphs 75 to 88 he explains that document tampering was endemic at the defendants and gives examples of techniques that were used. He concludes this section of his statement by saying: " he has serious concerns as to the authenticity of documents disclosed by the Defendants and relied on by the Court in the original trial."

(2) He is sceptical about the claimed loss of the May 2004 back-up tape and says that (a) that off-site storage run by Iron Mountain was "incredibly stringent" and (b) in the 25 years he worked for the defendants he never knew anything to go missing. Critically he says the Defendants would have retained copies of any back-up tapes. The claimant made the same point in his witness statement and it is notable that Mr Lowans, in his second statement, does not deal with the point. For present purposes it must be assumed to be accurate.

(3) He explains in some detail how the RMP and E-Flex worked and their respective purposes. He deals with E-Flex at paragraphs 41 to 49. He says it operated in tandem with the RMP and they were the two primary electronic systems for Customer's Facilities and Accounts. He says every loan, overdraft, supplemental agreement or security document requested by a relationship manager would be processed by the E-Flex system. He expresses the view that E-Flex would contain highly relevant information pertaining to the first claim. Importantly, it would reveal a record and an audit trail of who had accessed the claimant's account facilities and when and where changes were made.

(4) He explains at paragraphs 30 to 36 that every customer was given a unique number, a CIN. He provides an example of documents from the RMP system relating to the claimant that shows contradictory CIN numbers and says this cannot occur within genuine RMP documents as the CIN number is automatically 'electronically pulled through' the system and remains constant on genuine RMP documents.

(5) At paragraph 95 he expresses the opinion that a document dated 16 September 2009 is not genuine. At paragraphs 114 and 115 he points out that the document appears to have been signed electronically as being sanctioned on 3 August 2009, that is some time before the document is dated.

(6) His evidence lends some weight to the concerns expressed at paragraph 11(24) of the draft amended particulars of claim about the differences between documents disclosed in the first claim and those disclosed in response to the Data Subject Access Request.

(1) Mr Wright's evidence raises issues of fact that may make it inappropriate, if a properly pleaded case that meets the fraud threshold is produced, to grant summary judgment.

(2) The defendants' position is not aided by evidence from Mr Lowans that fails to provide a source or source of his evidence.

Appendix 1

"7. Documents disclosed by the Defendants a few weeks before trial from its internal customer relationship platform showed expiry dates on the Claimant's facilities of March 2020 (i.e. 16 years from the alleged promise made by Mr Mosley).

7.1.1 The whistle-blower has explained that there is no apparent excuse for such late disclosure because the full contents of the relationship manager platform are always downloadable and printable at the click of a button. The bank's conduct in this instance alone suggests a selective approach to disclosure.

7.1.2 A further electronic system within the bank's record-keeping, alongside the RMP system, is called 'E-Flex'. Nowhere in the disclosure exercise did the bank even reveal the existence of E-Flex still less disclose any documents from it. The function of E-Flex is to provide an electronic rubber stamp of who did what within the bank's computer system and on what day/time.

7.1.3 The whistle-blower will seek to provide evidence from direct experience of the bank deliberately taking advantage of claimants' solicitors' lack of knowledge about the bank's systems for document retention."

"11. The Claimant contends that by reason of post-trial discoveries and revelations he can show in this action that the Defendants were guilty of conscious dishonesty in the presentation and pursuit of the Defence,

(a) although not necessary, the Claimant contends that the dishonesty would have been determinative in the disposal of the Claim;

(b) although not necessary, the Claimant contends that he could not with reasonable diligence have discovered the matters of which he complains herein;

(c) although not necessary, the Claimant contends that the dishonesty was probably partly aimed at taking advantage of the inequality of arms in the litigation;

(d) the apparently credible material raising a prima facie case is:

PARTICULARS

(1) The Defendant manipulated disclosed documents. Print-outs from its electronic customer relationship platform show signs of some form of scrape by a find and replace facility the effect of which is to remove 'unwanted' text and automatically replace it with immediately opposing square brackets ([]). Merely by way of examples, an entry on the system made by Mr Mosley in February 2008 and marked by manuscript note "4/2/08 Decrease" reads,

"JMB Hire Limited. This is the new hire part of the operation. It doesn[]t actually own any machinery be[] re-hires from JMB 100 Ltd " (the missing, replaced text would seem to be 'cause');

A later entry from Mr Mosley marked by manuscript note "18/7/08 Renewal" reads,

"Declined to assist any further funding for this connection on either loan or overdraft. He has RBSIF waiting in the wings to assist where on the present debtor book could arguably uplift well over £100k if he so wish[] we are still pushing for the ID line";

An entry from Mr Mosley from September 2009 reads,

"£311k loan[] 14E years remaining. C&I repayments commenced September 2003";

Mr Coates, risk manager, has added to the same entry,

"Exit risk via open market [] PV needs to provide adequate positive commentary".

The insertion of the back-to-back square bracket symbol under a 'find and replace' facility is called a 'wildcard' and the effect of the facility is to make a once and for all automatic replacement across the entirety of a database such as the Defendants' relationship manager platform, wherever the unwanted text appears.

(2) The Claimant's complaint had been one of the 207 sample cases included within the FCA's Section 166 review regarding GRG's treatment of small and medium sized businesses and one of the 4 cases selected for Special Interview save that, because he was already in litigation, the Claimant did not proceed. The Claimant does not know whether the manipulation was caused by the Review, the litigation or both.

(3) The Claimant has discovered two different versions of handwritten notes made by Mr Brown of GRG made at a meeting shortly following the transfer of the Claimant's account to that division. The second copy appears to have a post-it note placed over some text so that the page photocopies without the text being visible. The document was also disclosed with heavy redaction by a four-inch solid black box covering the bottom part of the page of notes.

(4) The Claimant has discovered 2 identical versions of a review document dated 24 October 2009. One has a manuscript note not present on the other version and one shows a small line of redaction covering over the line which stated 'Security review undertaken (credit docs) no issues'. This is the 'SLS (renamed GRG) Internal Strategy and Credit Review Sheet'. The same unredacted document is contained separately within the electronic bundle of Bank disclosed documents AG 330-00001. A separate internal bank email dated 05.11.09 under the headings:

'Security Notes: ***** Special Notes *****'

states that:

'ORIGINAL CHARGE LOST. COPY FROM HMLR IN FILE'. A copy of a 'charge' document was later presented by the bank to the local County Court some time later in a 'Claim for Possession of Property' dated 7th September 2011 as an exhibit to a Statement of Truth signed by Chris Keane of Squire Sanders & Dempsey (UK) LLP, dated 20.07.11, the bank's then solicitors. It was marked as 'we certify that this is a true copy of the original Dated 7/2/11 Squire Sanders & Dempsey (UK) LLP'. At best it is likely not to be 'a true copy of the original', but is probably a 'copy of a previous copy' from the Land Registry. The Claimant believes that the redaction of specific text "Security Review undertaken (credit docs) no issues" was a deliberate attempt to conceal or distract from the fact that the bank at that time had lost the Security Charge Document.

(5) Following the learned Judge's dismissal of the Claim, the Claimant was able to make contact in July 2018 with a whistle-blower from the bank whose name had featured in several press and BBC articles examining GRG's dishonest practices and who had been a reporter to the FCA. He, a former senior RBS employee, informed the Claimant that large numbers of the Defendants' staff had routinely received specific training in how to falsify documents and including how to forge signatures. One of the techniques he specifically identified was the use of notes to cover text before photocopying with the shadow line created by the photocopier then being able to be concealed over a recopying exercise of up to 20 times. The whistle-blower explained that a phrase in common currency at the Defendants was "the best business is done at the photocopier". The Claimant was subsequently able to see from various mainstream media reports that the whistle-blower's revelations corresponded with other public accusations against the bank.

(6) The whistle-blower explained that it was common for the Defendants to copy and paste data from its RMP (relationship manager platform) system so as to produce selective disclosure when a customer was pursuing a formal complaint.

(7) The whistle-blower explained to the Claimant how he could see an electronic fingerprint on the RBS RMP system whenever an RBS employee accessed it. With the benefit of this information the Claimant was able to see that 16 of the Defendants' staff entered his RMP files on both 14 and 16 September 2009 which is the time the Defendants first imposed £3,000 monthly charges and new punitive interest rates on the Claimant and which Mr Brown of GRG described in his notes as 'penalty interest'. Other than these fingerprints however, there is no contemporaneous documentation (emails or otherwise) anywhere else to demonstrate that those individuals entered the system in that short period. Further, apart from this 3 day period, the same electronic fingerprints are largely missing from the rest of the RMP File Documents, whereas it would be expected that they would exist in the ordinary course of business with Mr Mosley and the other managers before the GRG transfer. The Claimant believes that the fingerprints might mark the period in which some manipulation of RMP was achieved.

(8) The whistle-blower suggested it would be in the Claimant's interests to speak to two former area bank managers operating a claims management company in Hull. The Claimant sought them out and learned that they had specific experience of the Defendants disclosing documents in litigation which were different to the same documents provided under a subject access request. They further explained that the Defendants operated a dishonest practice in respect of swaps/IRHP litigation of providing a covert credit line unknown to the customer which represented a contingent liability for the swap product and could be used by the bank to hedge against the chance of the agreement going awry for the customer and even on occasion to default the customer on loan to value breaches.

(9) The Claimant has become aware of a secret recording of the former RBS Director, John Hourican, from 2009 in which he admits the Defendant's routine use of 'data cleaners'.

(10) The Claimant contends that the Defendants have both admitted publicly in the recent past to allowing staff to recreate documents and having the software for such practices.

(11) The Claimant believes that widespread document manipulation is a complaint being pursued in an ongoing class action brought against RBS GRG by RGL Management, a claims management company.

(12) In some instances the Claimant now holds 4 different versions of the same bank document,

(a) A copy of the supposed original document

(b) A changed version with square brackets and a space

(c) A version identical to (b) but with the square brackets and space removed

(d) A version received under a post-trial subject access request with the square brackets and space removed and where the text has been copied into a new text box.

(13) The Claimant now sees there are numerous blank spaces within the RMP File that are out of sequence within the ordinary course of the documents. In size, the blank spaces are from circa one paragraph up to nearly an entire page.

(14) There are some documents which do not follow on as would be naturally expected in page order e.g. whilst the numbering might be page 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 the text at the head and foot of the documents does not flow or make sense i.e. a discrepancy between the numbering and document text.

(15) There are some 'text box' thick black perimeter lines broken in places with what appears to be the use of a 'white out' tool (e.g. a tipp-ex ribbon) that has strayed from deleting other text into the side of the text box. The Claimant has been alerted to this feature as a classic sign of document tampering.

(16) A document from the Supplemental Disclosure Bundle, File 1 of 2 no.71 contains handwritten notes from GRG Manager John Brown and shows several lines of text concealed by one or two pieces of paper (likely 'post it' notes) when utilising a photocopier. The notes are referring to the Claimant's then available assets within his business structure. This was at the time that GRG was promoting a debt for equity swap as an alternative to large capital repayments. The Claimant is aware that RBS operated a secret but now notorious property arm in conjunction with GRG called West Register which was used to acquire customers' property. Leaked RBS GRG & West Register Policies & Procedure Manuals were published in October 2016 by Buzzfeed in an article named "Dash for Cash". The West Register Manual reveals that RBS staff were instructed to send internal 'Victory Emails' when acquiring a borrower's property for the Bank's property arm West Register.

(17) Following the trial, the Claimant has checked the original meta data of just a small number of bank documents that retain their original meta data. The bank's electronic disclosure is split into two categories named "Images" and "Natives". Within the bank's disclosure of electronic documents, only a small number of electronic documents and a small number of Microsoft Excel spreadsheets created by GRG have retained original meta data. All the electronic documents under the 'Natives' heading should as 'Natives' retain their original meta data. GRG created a specific Microsoft Excel Spreadsheet that seemed to be renewed on an ongoing monthly basis. Of concern is the fact that GRG were supposed to have taken over the Claimant's accounts on the 30th June 2009 or 1st July 2009, according to the faxed GRG introductory document from Paul Mosley, and also as referred to by other bank documents. Within the bank's disclosure and taken from the witness statement of CRM Credit Manager Julie Gatfield, the handover to GRG was on the 14th May 2009, or alternatively within just days shortly afterwards, not later on the 30th June 1st July 2009. The Claimant has checked the original meta data of a particular monthly GRG spreadsheet from the bank's electronic disclosure document no. AG0000177 00001. The original meta data reveals that the date last 'saved' and also 'last printed' was '03.06.2009'. The document contains within it a section entitled 'Pricing/Upsides', where it states that:

"PPA potential uplift in site value should 'care village' idea materialise / fall back of existing PP to develop two properties and swimming pool."

This demonstrates, the Claimant avers, that GRG had identified a way of profiting from the secured property by way of exchanging debt for equity as early as 3rd June 2009, which is almost a full month before the official transfer to GRG had taken place, and a month before the first meeting with the Claimant on the 1st July 2009 (the 1st July 2009 is identified as the transfer date to GRG in the RBS GRG letter dated 23.12.09). The first meeting of the 1st July 2009 was where GRG was supposed to learn about the Claimant's business to enable to begin a process of turnaround/transfer back to the NatWest bank manager, as per the text of the introductory faxed letter from Paul Mosley and not for GRG to at their earliest opportunity seek a way of profiting from the secured property for the bank's benefit.

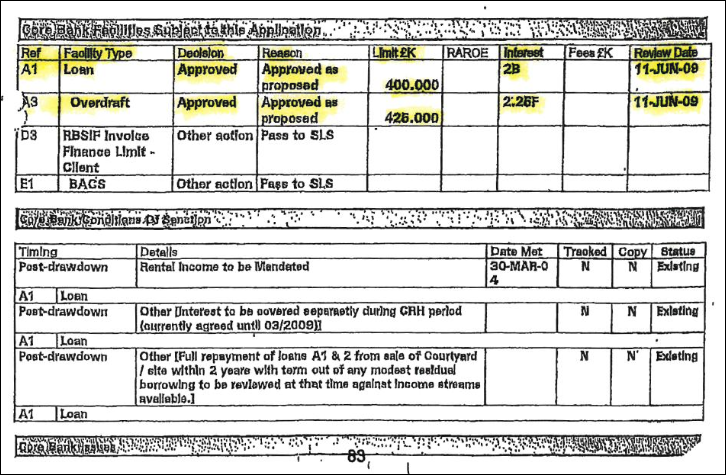

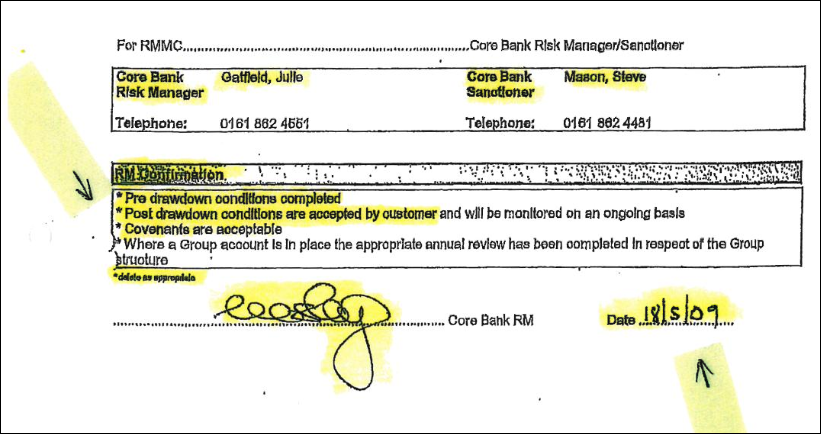

(18) There is an internal Transactional & Nontransactional Comments note purportedly written by GRG Senior Manager Mike Potts on the 09-Nov-09 that states that "All events of default to be preserved please." What is now clear from the second Supplemental Disclosure Bundle is that GRG renewed the Loan and Overdraft several times during 2009 until 4th December 2009, and in so doing extended the expiry date/term date of the loan and overdraft in writing within bank documentation. There is further documentation showing that RBS renewed the borrowing for some considerable time afterwards without the Claimant's knowledge. GRG and RBS repeatedly stated that the loan and overdraft were due for repayment on the 28th February 2009 were not repaid or renewed on that date; and therefore the Claimant was in default. This became an issue within the Judgment where aspects of the Claim were deemed by the learned Judge to be time barred as the Claim Issue date was 17th April 2015. The Julie Gatfield Witness Statement 'JAG1' with exhibits states that "I can see from the credit report that I renewed the facilities for a month, until 11 June 2009 . This would also have ensured that nothing showed up as overdue on the RMP system in the meantime". Within the Exhibits of JAG1, there is a 'Bank Sanction Summary Sheet' dated 5th May 2009. The A1 Loan and A3 Overdraft are 'Decision/ Approved' with a Review date of 11 June 2009. The document is signed by Paul Mosley on the 18th May 09, whereby immediately above his signature it states that:

* Post drawdown conditions are accepted by customer and will be monitored on an ongoing basis.

* Covenants are acceptable.

The Claimant says he was at no time informed that the loan and overdraft had been subject to a credit application at this time, nor did he have any knowledge that 'Post drawdown conditions are accepted by customer'. The fact that Paul Mosley signed this 'Bank Sanction Summary Sheet' on the 18th May 2009 was entirely missing from the Witness Statement of Paul Mosley. However, this matter is included within the Witness Statement of Julie Gatfield only.

The Claimant has a second version of the same summary sheet, otherwise the same, signed instead by 'Steve Mason' and undated.

There are several other references to the debt being due for repayment in June 2009 within GRG internal communications:

e.g. the GRG John Brown email dated 03.12.09 quote "Debt was due for repayment in June this year case transferred to GRG soon after".

Then 20 or so days later, GRG's John Brown wrote a letter to the Claimant dated 23.12.09, that stated "Your loan was due for repayment on 28th February 2009 and as such is in default. Your loan agreement clearly states that in such an event the interest rate shall be increased from 2.0% to 3.5% above base rate. This increase was not imposed until 10 August 2009 despite the loan being in default from 1 March 2009 . The overdraft also expired on 28 February 2009 .."

This letter was written just 20 or so days after writing within his internal email dated 03.12.09 that stated that "Debt was due for repayment in June this year".

The court was not referred to the fact that GRG covertly renewed the borrowing several times until 4th December 2009, which is demonstrated by the single late disclosed document File that arrived circa 5 weeks prior to trial (disclosure statement of truth signed 24th April 2018). During the course of the litigation, the bank's solicitors Addleshaw Goddard sent two substantive letters that the bank relied heavily upon asserting that 'there were no contemporaneous documents to support the Claimant's Claim'. The first letter dated 19 May 2017 states on page 2 at 2.5 & 2.6 that:

2.5 "It should be noted that the statements alleged are contrary to general banking practice. Why would a Bank agree a specific repayment date in writing, but then orally agree that it would not demand the monies for a far longer period?"

2.6 "In light of the above, and the evidence provided by your client to date, your client's collateral contract argument is entirely unsubstantiated. Put simply, there is no independent or contemporaneous evidence that suggests that the alleged statements might have been made. Your client's claim will therefore fail.

The second letter dated 15 September 2017 which is post standard disclosure states on page 1 at 1.1 that:

'Now that the parties have completed standard disclosure and we have had the opportunity to inspect those documents which have been disclosed by your client, we have reconsidered the contents of your 28 June 2017 letter in light of those documents. The short point arising out of our review is that there are no contemporaneous documents to substantiate the claims made by your client in respect of liability, causation or quantum. Accordingly, our view is strengthened that your client's claim is fundamentally flawed and bound to fail. The statements that there were no contemporaneous documents to support the Claimant's Claim were false.' Five or so weeks before the trial was due to begin on the 24th April 2018, a second tranche of supplemental disclosure (Disclosure Statement signed on the 13th March 2018) was served. The file contained numerous NatWest bank statements that had not been disclosed previously. The file also contained what became known at the trial as 'Credit File Front Sheets'. The Front Sheets contained numerous references to 'March 2020' being the expiry date of the Loan. This matched the alleged promise made by Paul Mosley in 2004. At trial the 'March 2020 Loan Expiry Dates' were deemed 'a mistake' that had carried through the documents by being accidentally 'auto populated' from one loan 'front sheet' to the next loan 'front sheet'. Within that late disclosure there were also however numerous 'Loan Application Forms' that also had entered upon them 'March 2020' as the expiry date of the Loan. It was, the Claimant avers, highly unlikely that the 'March 2020' date was also a mistake on the Loan Application Sheets, as Paul Mosley would have had to manually re-populate almost every text box within the Loan Application form, and to not alter/or correct the expiry date of 'March 2020'. That is improbable.

(19) At the first CMC hearing the Defendants specifically asked for extended time to give disclosure. The Claimant has recently discovered that RBS provided documents to the FCA's contractor Promontory on an electronic platform called 'RingTail'. He discovered this after a recent conversation with Duncan Burrell, Promontory's internal General Counsel in connection with a Data Subject Access Request to Promontory on the 12th April 2019. Mr. Burrell dealt with the DSAR. According to the bank's own disclosure documents, the bank also utilised the 'RingTail' platform as an electronic platform to transfer and store data relevant to the Claim. Most if not all of the documentation had always therefore been readily available and indeed utilised by the bank in the earlier Section 166 review. The Claimant fears that the District Judge was misled and the motivation may have been that the Defendants wished to alter some of the documents or data.

(20) According to the bank's first Disclosure Statement it could not locate 'the May 2004 monthly back up tape' from Iron Mountain. This would have no doubt contained the email traffic pertaining to the May 2004 Paul Mosley promises. The bank stated in correspondence that most of its documents would have been attached to bank emails at some time or other. The bank's location of the back up tapes for April and June 2004 but not May 2004 is suspicious. Iron Mountain have a highly effective professional document storage system that offers document/data tracing via advanced barcoding amongst other methods. Further, it is likely that a PLC such as a bank would have more than one copy of all back up tapes, mainly for security purposes, which makes it even more implausible that the bank could not locate this most important back up tape.

(21) The bank requested £1,000 per month per 4 custodians (there were 4 custodians Paul Mosley, Matthew Harvey, John Brown & Sharon Lewis) to restore back up tapes. The Claimant believes that the prohibitively expensive price was used to deter the Claimant from pressing for disclosure and deter the court from ordering it.

(22) After multiple requests to do so the bank did not supply Electronic Disclosure under its date range scope for Paul Mosley or Sharon Lewis prior to 1st April 2004 and in so doing deliberately missed the communications from March 2004 when the first substantial promises were made by Paul Mosley. Thus both the March and May 2004 disclosure was missed out. The basis for the bank's refrain that there were no supporting contemporaneous documents for the Claimant's case is obvious.

(23) The bank's response to the DSAR in April 2019 was manifestly defective because it did not produce documents which the Claimant already knew without doubt the bank held because they had been disclosed to him in the course of the litigation. The Claimant is now seeking formal enforcement through the Information Commissioner. The outcome of that regulatory enforcement will have a direct bearing on this action because it is expected to produce a definitive set of the documents held by the bank and that definitive set will allow the Claimant's allegations herein to be tested.

(24) Contrariwise, certain documents produced under the DSAR are different versions of documents disclosed in the litigation. Certain key sanction summary sheets obtained under the DSAR contain an additional column entitled 'expiry date/term'. The date entered for the expiry of the loan facility documents is 31 May 2020, i.e. consistent with the Claimant's original claim. Without cogent explanation for the discrepancy the Claimant can only infer that the corresponding sheets disclosed in the litigation were deliberately edited.

(25) The Claimant has now discovered that a written internal advice document created on 2 October 2007 had the expiry date/term entry altered from 31 May 2020 to 31 May 2008.

(26) In the light of his post-trial discoveries the Claimant has revisited the bank's disclosure generally. Close scrutiny has shown that a sanction summary sheet signed by Mr Mosley on 25/8/08 has been manually altered, with a 4 written over the 8 of the year and a 5 over the 8 for the month, thus to read 25/5/04. The Judge placed weight on the sheet because the typed terms were contrary to the Claimant's case, stipulating a requirement for full repayment of the facilities within 2 years (save for a possible review of modest residual borrowing against income streams available). The Claimant's belief now is that the sheet dates from 25/8/08, the date Mr Mosley signed against, and thus was after the point in time where the CRM (Customer Risk Manager) department had already removed his self-sanctioning powers as a result of his dealings with the Claimant, recording that 'the increases that have been auto approved have not helped (possible credit stewardship issues here'). It appears to be part of a crude attempt by Mr Mosley to cleanse the file and shelter from internal criticism or disciplinary action."

Note 1 Lord Briggs and Lady Arden gave dissenting judgments on the issue before the Supreme Court but also appear to have accepted the test in RBS v Highland Financial Partners as the correct one. [Back]