Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

England and Wales High Court (Chancery Division) Decisions

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> England and Wales High Court (Chancery Division) Decisions >> Lehman Brothers International (Europe), Re [2018] EWHC 1980 (Ch) (27 July 2018)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Ch/2018/1980.html

Cite as: [2019] Bus LR 1012, [2018] EWHC 1980 (Ch), [2019] BCC 115, [2018] WLR(D) 563

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [Buy ICLR report: [2019] Bus LR 1012] [View ICLR summary: [2018] WLR(D) 563] [Help]

Neutral Citation Number: [2018] EWHC 1980 (Ch)

Case No: 7492 OF 2008/CR-2008-000012 CR-2018-003713

IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE BUSINESS AND PROPERTY COURTS OF ENGLAND AND WALES COMPANIES COURT (Ch D)

The Rolls Building 7 Rolls Building Fetter Lane London, EC4A 1NL

Date: 27th July 2018

Before:

MR JUSTICE HILDYARD

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

IN THE MATTER OF LEHMAN BROTHERS

INTERNATIONAL (EUROPE) (IN ADMINISTRATION)

AND IN THE MATTER OF THE COMPANIES ACT 2006

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

MR. WILLIAM TROWER QC, MR. DANIEL BAYFIELD QC and MR. RYAN

PERKINS appeared for the Administrators of Lehman Brothers International (Europe) (In Administration).

MR. ROBIN DICKER QC, MR. RICHARD FISHER and HENRY PHILLIPS appeared for the Senior Creditor Group.

MR. DAVID ALLISON QC and MR. ADAM AL-ATTAR appeared for Wentworth.

MR. PETER ARDEN QC and MS. LOUISE HUTTON appeared for LB Holdings

Intermediate 2 Limited (In Administration) and its Administrators.

Hearing dates: 13 & 15 & 18 June 2018

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Judgment Approved

Mr Justice Hildyard:

Part A: the purpose and scope of this judgment, and the broad context of the application

1. The ultimate question considered in this judgment is whether the Court should sanction a scheme of arrangement between Lehman Brothers International (Europe) (in administration) (“LBIE”) and certain of its creditors pursuant to Part 26 of the Companies Act 2006 (the “CA 2006”). The Scheme has been proposed by LBIE’s Administrators pursuant to section 896(2)(d) of the CA 2006, which empowers an administrator to propose a scheme of arrangement on behalf of the company.

2. This is my second judgment in this matter. I have already provided, on 15 June 2018, a short ex tempore judgment sanctioning the Scheme. I considered that necessary in order to explain my decision both to the Court of Appeal given the then imminent hearing before it of one of the proceedings compromised by the Scheme, and to the US Bankruptcy Court, given the Administrators’ stated intention to apply on 19 June 2018 for recognition of the Scheme as a foreign main proceeding under Chapter 15 of the US Bankruptcy Code. However, as I indicated at the time, and with the encouragement of the parties, I have also thought it right, in the context of an administration which has been in being for nearly a decade and has involved multiple proceedings of very considerable value and complexity, to provide an additional full judgment elaborating my reasoning. I had hoped to provide this before the Scheme became effective; but it proved a more time-consuming task. This judgment should be read with the fact in mind that the Scheme has already come into effect; and any inappropriate use of tenses which abides should impliedly be corrected.

3. Turning to the substance of the matter, the basic purpose of the Scheme is to compromise various complex legal proceedings so as to facilitate the distribution of the surplus in LBIE’s estate (and, in due course, to bring the administration to an end). The Administrators present the Scheme as providing the only realistic way of enabling the distribution of the surplus in LBIE’s estate without years of further

litigation.

4. LBIE, an unlimited company incorporated in England and Wales, was the Lehman Group’s main trading company in Europe. It has been in administration since September 2008. Its immediate holding company, LB Holdings Intermediate 2 Ltd (“LBHI2”), which holds all of the ordinary share in its capital, has been in administration since January 2009. The purpose of each administration was to realise the respective assets of these companies to their best advantage, rather than the preservation of the companies as going concerns. Each has become a distributing administration.

5. The collapse of the Lehman Group in September 2008 shook the

financial world. Its effects are still being felt today. It is perhaps ironic that in the result, at least in the case of LBIE, the process of administration has yielded a very substantial surplus; and that the litigation sought to be resolved by the Scheme, and which is delaying the completion of administration, relates not to deficiencies but to the unusual legal issues relating to surplus assets (“the Surplus”).

6. After four dividends to creditors with an aggregate value of 100p in the £ (including distributions to unsecured creditors of approximately £12.6 billion), LBIE’s general estate contains liquid assets with a total value of some £6.6 billion. Total estimated future realisations range from approximately £1.2 billion to £1.7 billion. Although not all of these assets will be available (or, in any event, immediately available) for distribution as part of the Surplus, since it is necessary for the Administrators to hold a proportion of the assets in reserve for expenses and any unresolved provable debts, on any view, however, the Surplus is substantial.

7. There has never, at least in this jurisdiction, been an administration like it. The issues to which it has given rise have been correspondingly novel, with very considerable amounts in dispute. There has at every stage been every likelihood that the issues requiring resolution to establish rankings and priorities as to entitlement to the Surplus (in what has become known as the ‘Waterfall proceedings’) would eventually proceed to the Court of Appeal and onward to the Supreme Court: see, for example, Re Lehman Brothers International (Europe) (‘Waterfall I’) [2017] UKSC 38 (in the Supreme Court); Re Lehman

Brothers International (Europe) (Nos 6 and 7) (‘Waterfall IIB’) [2017] EWCA Civ 1462 (in the Court of Appeal) and In re Lehman Brothers Europe (No. 9) (‘Waterfall IIC’) [2017] EWHC 20131 (Ch), which, at the time of my earlier decision, was imminently due to come before the Court of Appeal at a hearing commencing on 3rd July 2018.

8. There are a variety of further proceedings, some still in the foothills, others well on their way up the judicial ladder. I shall return later to describe the matters in issue. For the present it suffices to say that prior to the implementation of the Scheme (a) there remained important issues outstanding (in the sense that they have not finally been determined) which could, according to their resolution, have a fundamental effect on the calculation of creditors’ entitlements to the Surplus and (b) until such proceedings (“the Relevant Proceedings”) were compromised or finally determined (such that all appellate processes have been exhausted), as I understand they now have been by effect of the Scheme, it would have been impossible for the Administrators to make further substantial progress in the distribution of the Surplus.

9. That is because, if the Administrators were to distribute the Surplus on a basis which was later held to be wrong by the Court of Appeal or the

Supreme Court, they would be exposed to the risk of personal liability. That is not a risk that any office-holder can reasonably be expected to bear. Thus, until the Relevant Proceedings are dealt with, the Surplus will remain locked in the estate.

10. Further long delay in the conclusion of the Administration is inherently unsatisfactory. But there is a further reason why delay is damaging to all creditors. Creditors’ entitlements to statutory interest (at 8%) ceased once all admitted provable claims had been paid in full (since the underlying debts have been paid), and creditors will not receive any compensation for the period during which the Surplus remains locked in the estate: see Re Lehman Brothers International (Europe) (Waterfall IIB) [2018] Bus LR 508 at [43]- [49] (Gloster LJ). In the context of such a substantial Surplus the effect is significant. I can take the following illustrative figures from the Administrators’ skeleton argument:

(1) Assume that the total amount of statutory interest is £5bn.

(2) Assume that creditors could earn an average total return of 15% over three years on any distributions made to them (representing a return of 5% per annum, without compounding). On that basis, the “time value” of £5bn over three years is £750m.

(3) If the Surplus is not distributed for three years, creditors would effectively lose £750m (being the assumed “time value” of £5bn), and would not receive any further statutory interest or other compensation for that loss.

(4) The figure of £750m is a conservative estimate. Nearly all LBIE’s investors are sophisticated investment funds or banks, which may be able to earn a significantly higher return than 15% over three years.

11. Any further delays will lead inexorably to a continuing loss of the time value of money, increasing with every day that the Surplus is not distributed. In such circumstances, the Administrators have had to consider whether any viable solution is available. They have concluded that (a) the existing judgments in the Waterfall proceedings already provide the Administrators with sufficient guidance to distribute the Surplus; (b) although any further appellate litigation might, of course, lead to a reversal of the existing judgments (to the benefit of some creditors and the detriment of others), such litigation is not necessary to enable the Administrators to distribute the Surplus; and (c) it is plainly desirable, looking at the interests of creditors as a whole, for the Administrators to pursue a compromise of the Relevant Proceedings so as to facilitate the distribution of the Surplus: and that is what the Scheme has been conceived to achieve.

Part B: structure of this Judgment and representation of creditors at the Hearing

12. After that introduction, I propose, in assessing whether to sanction the Scheme, largely to follow the sequence of the Administrators’ full and helpful skeleton argument, as follows:

(1) In Part C, I describe in greater detail both (a) the directions so far given by the Court on the basis of which the Administrators propose to proceed (and which the Scheme thus reflects) and

(b) the Relevant Proceedings;

(2) In Part D, I summarise the relevant terms of the Scheme (largely incorporating for that purpose the summary provided in the Administrators’ skeleton argument);

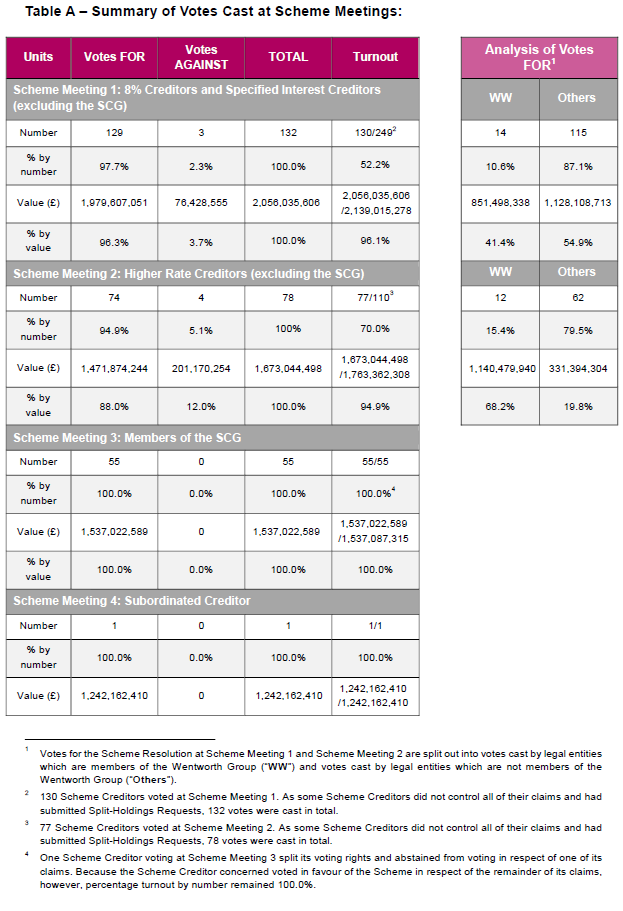

(3) In Part E, I describe the composition of the Scheme Meetings and the voting results at such meetings;

(4) In Part F, I set out the principles which are to be considered by the Court in determining whether to sanction a scheme such as

this;

(5) In Part G, I consider an important element in the application of those principles, being what significance the Court should attach to the voting results at the class meetings, and whether there were cross-holdings or other interests such as should reduce or negate reliance on the majority approvals that those votes expressed;

(6) In Part H, I consider the overall fairness of the Scheme, and in that context, objections put forward in respect of it in correspondence;

(7) In Part I, I address questions as to the Court’s international jurisdiction in respect of the Scheme and as to recognition internationally of the exercise of jurisdiction.

(8) Part J is my conclusion.

13. In my consideration of the Scheme I have been greatly assisted by Counsel and their respective teams, as follows (in the order in which they made oral submissions):

(1) Mr William Trower QC, Mr Daniel Bayfield QC and Mr Ryan Perkins appeared for the Administrators;

(2) Mr Robin Dicker QC, Mr Richard Fisher and Mr Henry Phillips appeared for supporting creditors, namely Burlington Loan Management Limited, CVI GVF (Lux) Master S.a.r.l, and Hutchinson Investors LLC (collectively, the “Senior Creditor Group”);

(3) Mr David Allison QC and Mr Adam Al-Attar appeared for another group of supporting creditors, namely the Wentworth Group, which comprises investment funds controlled by King Street and Elliott, LBHI, and certain SPVs, including, Wentworth Sons Sub-Debt S.à r.l. (the “Subordinated Creditor”) and Wentworth Sons Senior Claims S.à r.l.;

(4) Mr Peter Arden QC and Ms Louise Hutton appeared for LBHI2 and its Administrators.

14. The Wentworth Group and the Senior Creditor Group are the two largest creditors in the estate. The Senior Creditor Group holds approximately 40% of all admitted unsubordinated provable debts. The Wentworth Group includes: (i) the Subordinated Creditor (which holds the Sub-Debt); (ii) Wentworth Sons Senior Claims S.à r.l.; (iii) Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. (“LBHI”); and (iv) a number of investment funds controlled by King Street and Elliott. The entities referred to in (ii) to (iv) above hold approximately 38% of all admitted unsubordinated provable debts (the “Wentworth Senior Creditors”). The Subordinated Creditor is a member of the Wentworth Group but is not a Wentworth Senior Creditor, and does not hold any claims apart from the Sub-Debt. The shareholder of LBIE (LBHI2) also has an economic interest in the Wentworth Group.

15. It is an important factor to be acknowledged at the outset that, by reason of the quantum of their respective claims, both the Wentworth Group and the Senior Creditor Group hold a blocking position. That being so, it has always been essential that any proposed compromise should have the support of both the Wentworth Group and the Senior Creditor Group. This is an inescapable commercial reality.

16. Contrary to expectations voiced by three opposing creditors at the hearing to determine the composition of the classes to consider and vote upon the Scheme (“the Convening Hearing”), in the event no-one appeared before me at the Sanction Hearing to object to the Scheme. However, one of the creditors who opposed the class composition proposed by the Administrators and directed by the Court at the Convening Hearing, namely Deutsche Bank AG (“Deutsche”), also put forward in correspondence (through Clifford Chance) detailed objections to the sanctioning of the Scheme, though it withdrew its opposition shortly before the Sanction Hearing (by letter dated 11 June 2018). Further, two creditors, namely Goldman Sachs International (“GSI”) and SRM Global Master Fund Limited Partnership (“SRM”), raised concerns in correspondence which they asked to be considered and taken into account. SRM’s concerns largely mirrored concerns earlier raised by Deutsche. I shall address these concerns later notwithstanding that neither party exercised its right to attend by Counsel at either hearing, and I did not therefore have the benefit of adversarial argument.

Part C: the directions so far given and the Relevant Proceedings

17. The Waterfall proceedings have been sponsored (as it were) by the Administrators for the purposes of obtaining directions as to the admissibility of certain categories of claims and as to the rankings or priorities between creditors. The form of the proceedings has been that in the context of an application for directions, parties have been selected to represent competing interests with a view to enabling the Court to resolve the matter after full adversarial contest. The parties so selected have not formally been appointed representative claimants or defendants: but all creditors have been notified of the proceedings and in substance the results are intended to bind them all, given the Administrators’ express purpose and intention of acting in accordance with the Court’s decisions on those applications.

18. Amongst the principal concerns and disputes in this context have been:

(1) Whether the Sub-Debt claims ranked ahead or behind statutory interest claims pursuant to rule 2.88(7) of the Insolvency (England and Wales) Rules 2016 (the “IR 2016”);

(2) Whether creditors who had suffered a currency loss as a result of the conversion of their debts from foreign currency into sterling as at the date of the commencement of the administration could claim and prove for such losses, and if so whether such a claim would rank ahead of or behind the Sub-Debt claims and/or statutory interest claims;

(3) Whether contractual interest was provable or statutory interest was payable for the period of administration if it was immediately followed by a liquidation.

19. On final appeal in Waterfall I the Supreme Court determined that (1) statutory interest ranks in priority to the Sub-Debt; (2) currency conversion claims do not exist; and that (3) the insolvency regime contains a “lacuna” such that, if LBIE moves from administration into liquidation, any unpaid statutory interest under rule 14.23(7) in respect of the period between the commencement and the termination of the administration would not be payable out of the Surplus or provable in the liquidation.

20. In simplified terms (and ignoring various complications which are not material for present purposes), it now seems clear, since that decision of the Supreme Court in Waterfall I, that the Surplus must be distributed in the following order of priority:

(1) First, the Surplus must be applied towards the payment of statutory interest in accordance with rule 14.23 of the IR 2016. Statutory interest is payable on provable debts at the greater of 8% per annum or the “rate applicable to the debt apart from the administration” (typically a contractual rate): see rule 14.23(7). Some creditors have a contractual discretion to certify the rate of interest applicable to their claims, which could (in principle) enable them to claim statutory interest at a rate greater than the 8% minimum. However, the exercise of any such contractual discretion is capable of giving rise to a number of disputes, and creates significant uncertainty in quantifying the total amount of statutory interest which falls to be paid: see below. Total statutory interest entitlements are likely to exceed £5bn, and are likely to be paid in full out of the Surplus.

(2) Second, after statutory interest and any non-provable liabilities have been paid in full, the Surplus must be applied towards the payment of the subordinated debt (the “Sub-Debt”) held by Wentworth Sons Sub-Debt S.à r.l. (the “Subordinated Creditor”, as previously defined). As its name indicates, the Subordinated Creditor is part of the Wentworth Group. The ranking of the SubDebt was established by the decision of the Supreme Court in Re Lehman Brothers International (Europe) (Waterfall I) [2017] 2 WLR 1497 at [56] (Lord Neuberger). The Sub-Debt has a total value of approximately £1.24bn (excluding interest).

(3) Third, any remaining Surplus falls to be distributed to LBHI2 as the sole shareholder of LBIE. LBHI2 has an economic interest in the Wentworth Group. A possible mechanism for effecting a distribution to LBHI2 is described in Re Lehman Brothers Europe Ltd (No. 9) [2018] Bus LR 439 (Hildyard J) at [22].

21. There remained, however, a variety of disputes as to (1) the calculation of statutory interest, (2) the extent of entitlements to contractual interest under ISDA Master Agreements and similar contracts and (3) the admission of proofs disputed by other creditors. Thus, although two further applications (known as the Barclays Application and Waterfall III) have been compromised, there remained outstanding the Relevant Proceedings, which can briefly be summarised as follows:

(1) The Waterfall IIA Application. The Waterfall IIA Application raised a number of questions relating to the calculation of statutory interest, including, most significantly (in financial terms), whether dividends paid in the administration should be treated as notionally having discharged interest before principal. This is known as the Bower v Marris issue, after the case of the same name: see (1841) Cr & Ph 351. In October 2017, the Court of Appeal upheld the judgment of David Richards J at first instance: see [2018] Bus LR 508. As at the date of the Sanction Hearing, there was a pending application by the Senior Creditor Group for permission to appeal to the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court had agreed to postpone its determination of that application to facilitate the implementation of the Scheme. If the Scheme were not to become effective, the Supreme Court would be invited to determine the application. If the Scheme were to become effective, the application would be dismissed by consent.

(2) The Waterfall IIC Application. The Waterfall IIC Application raised a number of questions relating to the exercise of a contractual discretion to certify a rate of interest under various financial master agreements (including, in particular, ISDA Master Agreements). The hearing of the appeal (brought by the Senior Creditor Group and GSI) against my judgment (reported at [2016] EWHC 2417 (Ch), [2017] Bus LR 1475) was listed to commence before the Court of Appeal on 3 July 2018. If the Scheme were to become effective prior to that date, the appeal would be withdrawn by consent. Otherwise, the appeal would proceed. The Court of Appeal had been informed of the Sanction Hearing for the Scheme, but had declined to re-list the Waterfall IIC appeal for a later date until the outcome of the Sanction Hearing was known.

(3) The Olivant Application. This was an application by the Subordinated Creditor to challenge the Administrators’ decision to admit a proof of debt submitted by another creditor known as Olivant Investments Switzerland S.A. (“Olivant”). The application was made pursuant to rule 14.8(3) of the IR 2016, which provides a procedure whereby one creditor can challenge the admission of another creditor’s proof. In December 2017, I gave directions for the trial of various preliminary issues following a lengthy CMC, commenting as follows:

“This is another episode in the saga of the Lehman administrations, reflecting continuing disputes between rival creditors in the multitude of companies still in administration as they seek to obtain for themselves a greater share of the considerable surpluses which have been collected.”

(4) The Lacuna Application. This application arose out of the Supreme Court’s conclusion (in the Waterfall I decision) that, if LBIE moves from administration into liquidation, any unpaid statutory interest under rule 14.23(7) of the IR 2016 in respect of the period between the commencement and the termination of the administration would not be payable out of the Surplus or provable in the liquidation. That conclusion has come to be known as the “lacuna issue”. The Subordinated Creditor has attempted, in reliance on the lacuna issue, to take steps towards placing LBIE into liquidation before statutory interest can be paid to creditors. In response to those attempts, the Administrators applied for directions in January 2018.

22. The Lacuna Application and the Olivant Application were stayed by consent on 12 January 2018, to facilitate the implementation of the Scheme. If the Scheme were to become effective, the Olivant Application and the Lacuna Application would be withdrawn. If the Scheme did not become effective, the stay would be lifted, and the Olivant Application and the Lacuna Application would proceed before the High Court.

23. Failing a compromise of all the Relevant Proceedings, the Administrators estimated (and no one before me suggested any more optimistic view) their likely continuance until 2020 at the very earliest. Repeated appeals to the Supreme Court would be entirely foreseeable and perhaps inevitable. Moreover, it seemed entirely possible that new applications similar to the Olivant Application (where one creditor challenges the admission of another creditor’s proof) could be brought.

As I put it in Wentworth Sons Sub-Debt S.à r.l. v Lomas [2017] EWHC 3158 (Ch) at [18]:

“… the [Olivant] Application raises inevitably the status and effect, not only of the Olivant CDD, but potentially of all Claims Determination Deeds entered into by LBIE, of which there have been many, in aggregate of very considerable value. To some of these Wentworth and/or members of the SCG are party. In such circumstances, the Administrators are concerned that this Application could merely be the first in a series of similar challenges under Rule 14.8(3). The outcome of this Application therefore has, at least potentially, broader ramifications for the administration of LBIE.”

24. The Administrators were satisfied that the Scheme represents the only fair and realistic way to prevent many more years of continued litigation and to facilitate the distribution of the Surplus. In the absence of the Scheme, they reached the conclusion that no other solution would be likely to be available: in all likelihood, the litigation would simply continue for the foreseeable future.

Part D: summary of the terms of the Scheme

(a) Application of the Scheme

25. Subject to express exceptions (see below), the Scheme is intended to bind all legal or natural persons who have any “Provable Claim” (as defined in the Scheme) against LBIE, whether paid or unpaid (the “Scheme Creditors”). It is to be noted that for the purposes of the Scheme, the definition of “Scheme Creditor” expressly extends to a person holding Sub-Debt, such extension possibly being necessary (at least for the avoidance of doubt) in light of the view of David Richards J (as he then was), which was approved (in preference to the view of the Court of Appeal) by Lord Neuberger in the Supreme Court in Waterfall I (at [68] to [69]) that no proof can be lodged for the SubDebt until all “Senior Liabilities” have been paid in full.

26. The claims of a Scheme Creditor in respect of statutory interest entitlements are also within the scope of and intended to be compromised by the Scheme. Indeed, since the vast majority of provable debts have already been discharged in full, creditors’ statutory interest entitlements are the primary claims which are compromised by the Scheme.

27. The following creditors are excluded from the Scheme: (i) Storm Funding Limited (“Storm”); and (ii) any Relevant Employees or Relevant Jurisdiction Clause Creditors (as defined below) who have not lodged a proof of debt in LBIE’s administration. As to these

creditors:

(1) Storm has undertaken to be bound by the Scheme. This reflects the fact that Storm has a bespoke arrangement in relation to statutory interest pursuant to a commercial settlement dated 17 March 2014, which provides that any payment made to Storm in respect of statutory interest would be paid in respect of its admitted claim at an effective rate of 8% simple interest per annum, but calculated from a date later than the date of the commencement of LBIE’s administration to the date when Storm's admitted claim was paid in full. Storm and the Scheme Creditors are collectively described as the “Scheme Parties”. For convenience, in this Judgment I refer simply to the Scheme Creditors, but it should be understood that Storm is also bound.

(2) The purpose of excluding from the Scheme any Relevant Employees or Relevant Jurisdiction Clause Creditors who have not lodged a proof of debt in LBIE’s administration relates to a jurisdictional issue explained below.

(3) LBHI2 (in its capacity as shareholder of LBIE) is not a Scheme Creditor but has signed a deed of undertaking containing certain obligations in connection with the Scheme given in consideration for third party rights and undertakings granted in LBHI2’s favour.

(b) Termination of Relevant Proceedings

28. Pursuant to the Scheme, and in accordance and fulfilment of its principal objective, the Relevant Proceedings will be brought to an end. This will involve: (i) the withdrawal of the application for permission to appeal to the Supreme Court in the Waterfall IIA Application (such that the judgment of the Court of Appeal is final and binding); (ii) the withdrawal of the appeal to the Court of Appeal in the Waterfall IIC Application (such that the judgment at first instance is final and binding); and (iii) the withdrawal of the Olivant Application and the Lacuna Application. Under the terms of the Scheme the Administrators are given authority to provide and file the relevant court documentation for these purposes. (c) Waiver of challenge and appeal rights

29. Further:

(1) Each Scheme Creditor waives its right to challenge the admission of any other creditor’s proof of debt (where the relevant proof was admitted prior to the Record Date). This will avoid the risk of the Olivant Application being repeated for other proofs of debt, which would be likely to lead to significant delays and costs.

(2) Subject to certain exceptions, each Scheme Creditor waives its right to appeal any first instance decision (of any court of competent jurisdiction) which relates to an exercise of the Administrators’ functions after the date when the Scheme becomes effective (the “Effective Date”). Thus, by way of example, in the unexpected event that a new proof of debt is submitted prior to the Effective Date and rejected by the Administrators after the Effective Date, any challenge to the Administrators’ decision would be resolved by the High Court, and there would be no possibility of any appeal to the Court of Appeal or the Supreme Court. This provision is intended to avoid the substantial delays and costs that would be likely to result from appellate proceedings.

(c) Bar Date

30. In order to enable the Administrators to distribute the Surplus, it is necessary to determine the total quantum of provable claims against LBIE. As matters stand, there is nothing to prevent creditors from lodging new proofs (despite the fact that the administration has been ongoing for nearly a decade). Any such new proofs could affect the size of the Surplus available for distribution to others.

31. To that end, and conventionally, the Scheme imposes a bar date for the submission of claims (the “Bar Date”). Subject to certain exceptions, any claims held by a Scheme Creditor which have not been notified prior to the Bar Date will be discharged on that date. The Bar Date applies to all types of claims held by a Scheme Creditor: that includes provable claims, non-provable claims and expense claims (subject to certain exceptions).

32. Less conventionally, the Bar Date is fixed as the date when the Scheme becomes effective (the Effective Date). It would be more conventional to provide a longer period before the bar. The unusually short period is presented as justified in the context of the fact that the administration has been ongoing for a nearly a decade, and that the Administrators first invited creditors to prove their claims in December 2009. Further, creditors were notified of the intention to impose a Bar Date on 22 December 2017, and the Bar Date is clearly signalled in the First Practice Statement Letter (paragraph 6.1.4) dated 18 April 2018 and sent to Scheme Creditors in accordance with the usual practice.

(e) Statutory Interest Claims and the adjudication process

(i) The various statutory interest entitlements

33. Central to the Scheme is the mechanism it provides for the

adjudication of creditors’ statutory interest entitlements, effectively in substitution for the Relevant Proceedings. I shall return later to assess the fairness of the mechanism: I confine myself now to a statement of its essential features, as described in the Applicants’ skeleton argument (which statement I gratefully adopt with only minor alterations).

34. Three groups of creditors must be distinguished in this regard:

(1) 8% Creditors. As noted above, statutory interest is payable on provable debts at the greater of 8% per annum or the “rate applicable to the debt apart from the administration” (typically a contractual rate): see rule 14.23(7). For many creditors, there is no “rate applicable to the debt apart from the administration”. Such creditors can only receive interest at the statutory minimum of 8% per annum. These creditors are described as “8% Creditors”.

(2) Specified Interest Creditors. One claim arises under a contract which requires LBIE to pay a specific rate of interest in excess of 8% per annum. The sole creditor holding this claim is described as the “Specified Interest Creditor”.

(3) Higher Rate Creditors. A number of claims arise under financial master agreements which give the creditor a contractual discretion to determine the rate of interest payable by LBIE. For example, the

ISDA Master Agreements require LBIE to pay interest at the “Default Rate”, which is defined as the “rate per annum equal to the cost (without proof or evidence of any actual cost) to the relevant payee (as certified by it) if it were to fund or of funding the relevant amount plus 1% per annum”. The relevant payee has a broad discretion to certify its cost of funding. There are similar provisions in the AFB/FBF French Master Agreements (which empower the payee to certify its “overnight refinancing rate”) and the AFTB French Master Agreements (which empower the payee to certify its “average overnight rate”). A certificate cannot be impugned unless it was made irrationally or in bad faith, or the certificate was founded on a manifest numerical or mathematical error or otherwise than in accordance with the Waterfall IIC judgment: see Re Lehman Brothers International (Europe) (No. 6) (Waterfall IIC) [2017] Bus LR 1475 at [207] (Hildyard J). Creditors holding claims arising under an ISDA Master Agreement,

AFB/FBF French Master Agreement or AFTB French Master Agreement are described as “Higher Rate Creditors”. These creditors may be able to claim more than the statutory minimum of 8%, depending on the outcome of the certification process.

35. The Scheme provides for the statutory interest entitlements of the 8% Creditors and the Specified Interest Creditors to be calculated in accordance with the existing Waterfall judgments. For example, the Administrators will proceed on the basis that the rule in Bower v Marris does not apply to the calculation of statutory interest (as David Richards J and the Court of Appeal held in the Waterfall IIA Application), and no further appeal to the Supreme Court in relation to that issue will be possible: see above.

36. Further, the Scheme contains a detailed procedure for determining the statutory interest entitlements of Higher Rate Creditors. The avowed purpose of the procedure is to ensure that the statutory interest entitlements of Higher Rate Creditors can be determined in a manner that is both fair and expeditious, so as to avoid protracted disputes which could delay the distribution of the Surplus. The procedure can be summarised as follows:

(1) Each Higher Rate Creditor is entitled to elect between two

alternative options:

(a) The first option is for the creditor to receive statutory interest at a simple rate of 8% per annum, plus an additional payment equal to 2.5% of the value of the creditor’s admitted provable claim (the “Settlement Premium”) in full and final satisfaction of the creditor’s statutory interest entitlement. The Settlement Premium represents the quid pro quo for waiving the right to certify a rate higher than the statutory minimum of 8%. Alternatively:

(b) The second option is for the creditor to certify the rate and amount of interest applicable to the creditor’s claim in accordance with the underlying contract.

The certification must be submitted by the Effective Date. Creditors who choose the second option are not entitled to receive the Settlement Premium.

(2) The stipulated deadline for certification is the Effective Date. The justification advanced for this (which I have accepted) is as follows: (i) the first progress report which disclosed the possibility of a surplus in the estate was issued in April 2013 (at which point all Higher Rate Creditors should have realised that certification could be necessary); (ii) the Waterfall IIC judgment was handed down in October 2016 (which set out the key legal principles relating to certification); and (iii) creditors have been aware of the proposed certification deadline since 18 April 2018, when the first Practice Statement Letter (“First PSL”) was circulated; so that (it is submitted) (iv) Higher Rate Creditors have had sufficient time to assess whether to certify and prepare any such certification. This is borne out by the Chairman’s Report: see below.

(3) If a Higher Rate Creditor failed to make an election at the time of voting on the Scheme, the creditor is deemed to have elected to receive the Settlement Premium.

(4) Where a Higher Rate Creditor submits a certification by the Effective Date, LBIE may either: (i) accept the certification; (ii) reject the certification entirely (on the basis that the creditor should not receive more than the statutory minimum of 8%); or (iii) make a counter-offer (higher than the statutory minimum but lower than the certified amount).

(5) If the Higher Rate Creditor is not satisfied with LBIE’s decision, the creditor is entitled to require that the dispute be resolved by an independent adjudicator.

(iii) Key features of adjudication process

37. The key features of the adjudication process are as follows:

(1) The adjudicator will be either Sir Bernard Rix, Michael Brindle QC or Tim Howe QC (or, if none of them is available, another English law-qualified QC or retired judge).

(2) The adjudicator will act an as expert, not an arbitrator.

(3) The adjudication will be determined on paper, without an oral hearing. The relevant Higher Rate Creditor and LBIE are both entitled to file written submissions and supporting evidence.

(4) In reaching a decision, the adjudicator must have regard to a number of legal principles referred to as the “Relevant Principles”. These are set out in the Explanatory Statement prepared by the Company and the Administrators, and dated 31 May 2018.

(5) The Relevant Principles comprise the following: (i) the principles set out in the judgment and order in the Waterfall IIC Application;

(ii) the principles relating to the AFB/FBF French Master Agreements which were agreed to be correct by the parties to the Waterfall IIC Application (but which were not the subject of any formal determination by the Court); (iii) the principles set out in the judgments and orders of David Richards J and the Court of Appeal in the Waterfall IIA Application; and (iv) a further principle regulating the calculation of the amount of Statutory Interest defined in the Scheme as the Compounding Principle, and further explained subsequently in the Scheme.

(6) Although the adjudicator must “have regard” to the Relevant Principles, it is recognised that these principles do not provide an exhaustive codification of the law. The parties are able to file legal submissions in relation to any issues which may arise, and the adjudicator is entitled to take those submissions into account when reaching his decision.

(7) The adjudicator must uphold the creditor’s certification unless the adjudicator is satisfied, on the balance of probabilities, that it was made irrationally, in bad faith, or contrary to the Relevant Principles. The burden of proof falls on LBIE. (There is also a mechanism for addressing and correcting any mathematical or numerical errors which the adjudicator identifies.)

(8) If (and only if) the adjudicator concludes that the certification was made irrationally, in bad faith, or contrary to the Relevant Principles, then the adjudicator must award the creditor the statutory minimum of 8% or (if any counter-offer was made) the amount of LBIE’s counter-offer. There is no other option available to the adjudicator. In particular, the adjudicator is not permitted to award some amount falling between the creditor’s certification and LBIE’s counter-offer.

(9) The timetable for the adjudication is deliberately compressed, as explained in a useful flow chart at Part II, paragraph 10.10 of the Explanatory Statement, which identifies the number of business days between each step in the adjudication process. For example, once the adjudicator receives LBIE’s written submissions, the adjudicator is required to use reasonable endeavours to reach a final decision within 20 business days.

(10) The adjudicator will not give reasons for the decision; and that decision is final and binding, and is not capable of being appealed (except in the case of fraud or bias by the adjudicator).

38. The costs of the adjudication follow the event: they must be paid by LBIE or by the creditor, based on the “loser pays” principle.

39. Another important facet of the proposed adjudication system, and one which caused controversy, is the special role accorded to the Wentworth Group. In the course of negotiations leading to the development of the Scheme, the Wentworth Group stated that it would only support the Scheme if the Subordinated Creditor was permitted to have input in respect of the determination of matters which are likely to affect the recovery of the Sub-Debt. The upshot is that the Scheme requires LBIE to engage with the Subordinated Creditor in relation to various matters. For example:

(1) LBIE must consult with the Subordinated Creditor in deciding whether or not to accept a certification, although LBIE has the sole discretion as to whether or not to accept any certification.

(2) LBIE must consult with the Subordinated Creditor as to the amount of any counter-offer, although (once again) LBIE has the sole discretion as to the amount of any counter-offer. The counteroffer must be made in accordance with the Relevant Principles. (Under a previous version of the Scheme (which was placed before the Court at the Convening Hearing), the Subordinated Creditor had the right to determine the amount of any counter-offer. Some creditors objected to this provision at the Convening Hearing. In order to accommodate the concerns that were raised, the Scheme was amended (prior to the Scheme Meetings) so as to remove the Subordinated Creditor’s right to determine the amount of any counter-offer. That right is now vested in LBIE, and the Subordinated Creditor merely has a right of consultation.) Thus, the Subordinated Creditor cannot require LBIE to make a counteroffer: if LBIE considers that the creditor’s certification should be accepted without any modification, that outcome cannot be prevented by the Subordinated Creditor. Further, the counter-offer can be rejected and the matter appealed through the adjudication procedure.

(3) Where a certification is subject to adjudication, LBIE must use reasonable endeavours to appoint (in order of priority) Sir Bernard Rix, Michael Brindle QC or Tim Howe QC as the adjudicator. If such individuals are not able to accept the appointment, then another suitably qualified candidate (who must be an English lawqualified QC or former judge[1]) will be selected in consultation with the Subordinated Creditor. However, the final decision as to the selection of the adjudicator rests with LBIE and the terms of appointment are to be agreed by LBIE without regard to the Subordinated Creditor.

(4) During the “Consultation Period” (where LBIE and a certifying Higher Rate Creditor are seeking to agree the amount of the certification), the Subordinated Creditor is entitled to receive information relating to the negotiations, including confidential information. The Subordinated Creditor is under an obligation to keep such material confidential, and not to use such material for a collateral purpose. The information must be destroyed or returned to the Company once it is no longer reasonably required for the purposes of the Scheme. These information rights are a necessary consequence of the Subordinated Creditor’s consultation rights as set out above, since it is impossible to consult without the relevant information.

40. Having considered the matter carefully, the Administrators are satisfied that it is appropriate for the Subordinated Creditor to be involved in this way. Where a Higher Rate Creditor certifies its cost of funding, the Subordinated Creditor has a significant economic interest in the outcome of the certification and adjudication process. It is therefore appropriate for the Subordinated Creditor to play a role in the process. Quite apart from the provisions of the Scheme, the Administrators would be expected to consult with the Subordinated Creditor on matters affecting its interests, and the Subordinated Creditor would be entitled to intervene in any legal proceedings relating to a disputed certification: see below.

(f) Other matters relating to the Scheme: Lock-Up Agreement and consent fee

41. The Wentworth Group and the Senior Creditor Group have entered into a lock-up agreement dated 22 December 2017 (the “Lock-Up Agreement”), pursuant to which they have agreed to support the Scheme. Further details relating to the Lock-Up Agreement are set out in the First PSL published on 18 April 2018 at paragraphs 5.11 to 5.16.

42. Also pursuant to the Lock-Up Agreement, the Wentworth Group and the Senior Creditor Group have agreed to accept the Settlement Premium in respect of all Higher Rate Claims (rather than seeking to certify their cost of funding).

43. The Lock-Up Agreement does not provide for the payment of any consent fee, however:

(1) Late in the evening on 25 April 2018 (after the First PSL had already been circulated to creditors), the LBIE Administrators received a letter from LBHI2’s administrators [CH2/RD2/8] which indicated that Wentworth Sons Senior Claims S.à r.l., the Subordinated Creditor and certain members of the Senior Creditor Group had entered into a separate settlement agreement in parallel with the Lock-Up Agreement (the “Settlement Agreement”).

(2) The Settlement Agreement provided that (amongst other things) the Senior Creditor Group would receive from those Wentworth parties the sum of £35m by way of a “consent fee” in the event that the Scheme becomes effective. The Administrators received a copy of the Settlement Agreement on 29 April 2018.

(3) No similar consent fee was offered to other creditors. The Administrators had not previously been aware of these arrangements. As a result of this disclosure, the Administrators sent a second PSL (the “Second PSL”, published on 2 May 2018) referring to and explaining the consent fee, and proposing that the Senior Creditor Group should vote in a separate class in order to avoid a dispute about class composition: see below.

(g) Third party releases

44. The Scheme additionally provides for the release of the following claims by Scheme Creditors against third parties:

(1) Any “Administration Claims (being Claims against the Administrators or the Released Third Parties (who are parties connected to the Administrators, their firm or the Company), where such Claims arise from actions taken by such person on or after the Administration Date but prior to the Effective Date), but only to the extent that the Administrators or Released Third Parties would have an indemnity or other similar claim against the Company”; and

(2) Subject to certain exceptions, any “Released Scheme Implementation Claims (being Claims against the Company, the Administrators, the Released Third Parties or the Locked-Up Parties) where such Claims arise from or in connection with action taken by any such person on or after 1 November 2017 in relation to the proposal or implementation of the Scheme)”.

(3) There are also various releases in favour of LBHI2, e.g. in relation to any Creditor Contributory Claim Rights (as defined).

45. The give and take evident in these provisions is clear. There is no doubt that the Scheme constitutes a “compromise or arrangement” within Part 26 of the CA 2006 (as those words were explained in Re Savoy Hotel Ltd [1981] Ch 351 and Re NFU Development Trust Ltd [1972] 1 WLR 1548). That is, of course, a necessary condition for the application of Part 26 and it is appropriate to record its satisfaction in any event; but I do so in this case also because in correspondence one creditor (Deutsche) at one time suggested that the Scheme was not a “compromise or arrangement”, though the suggestion, which was never explained, was (rightly, so it appears to me) not pursued.

46. The questions then are whether the Scheme has been approved by appropriately constituted classes and, if so, whether it is fair and free from ‘blot’ so that the Court should give it its sanction.

Part E: composition of classes and the Scheme Meetings

47. The first in the three stages (after development of the proposals themselves of course) which are mandated by Part 26 of the CA 2006 before a scheme may be sanctioned is an application to the Court for an order convening Scheme Meetings to consider and vote on the Scheme.

48. In this case, the Administrators applied (by Part 8 claim form) for such an order on 2 May 2018, and on 18 April 2018 published the First PSL as required by present practice (see Practice Statement [2002] 1 WLR 1345, “the Practice Statement”), followed by a Second PSL (dated 2 May 2018) in circumstances already described.

49. The Convening Hearing (as such hearings are often referred to) took place before me on 9, 10 and 11 May 2018. The Administrators submitted that the Scheme Creditors should vote at four Scheme Meetings, namely:

(1) A meeting of the 8% Creditors and the Specified Interest Creditor, excluding claims legally held by the Senior Creditor Group (the “8% Meeting”);

(2) A meeting of the Higher Rate Creditors, excluding claims legally held by the Senior Creditor Group (the “Higher Rate Meeting”);

(3) A meeting of all members of the Senior Creditor Group (the “SCG

Meeting”); and

(4) A meeting of the Subordinated Creditor (the “Subordinated Creditor Meeting”).

50. At the Convening Hearing, the Administrators’ proposals were opposed by three creditors, namely Deutsche and CRC Credit Fund Limited (“CRC”), both of which are Higher Rate creditors, and Marble Ridge Special Situations GP LLC (“Marble Ridge”) which also is a Higher Rate creditor. These creditors were represented respectively by Mr Andrew Twigger QC, Mr Andrew de Mestre and Ms Hilary Stonefrost.

51. After adjourning for a short time to consider the matter, I accepted these proposals, and made a Convening Order accordingly, for reasons that I sought to set out fairly summarily in an oral judgment, now I think to be found at [COUNSEL PLEASE COMPLETE].

52. When I gave that judgment, I anticipated that there would or might be further evidence adduced, especially as to the claimed identity between all the Wentworth companies. In the event, however, CRC and Marble Ridge voted in favour of the Scheme (after its amendment in respect of aspects of the adjudication process) and (as previously mentioned) Deutsche has withdrawn its objection stating in its solicitors (Clifford Chance’s) letter of 11 June 2018 that it

“does not…object to the court’s sanctioning the proposed scheme, should the court see fit to do so.”

53. GSI, which did not appear at the Convening Hearing or the Sanction Hearing, indicated in correspondence (and, in particular, in a letter to the Administrators dated 5 February 2018) which was before the Court and carefully considered at the Convening Hearing, its “concerns relating to both the process by which the Proposed Scheme has been developed, and the substance of the Proposed Scheme”, and I took it to support Deutsche’s objections. But GSI never made clear any other reasoned basis for objection to the class composition; and, as I say, did not see fit to pursue that before me at either hearing other than in the somewhat indirect way I have described, save in one instance. The one instance is this: during the course of the Sanction Hearing its solicitors, Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton LLP (“Cleary Gottlieb”) requested the Administrators specifically to draw to my attention two matters by reference to a table in the Chairman’s Report on the meetings, which record the voting results at the four class meetings. I shall return to these matters in due course; but I shall first describe the procedure and results at the four meetings. Procedure and voting results

54. The Chairman’s Report on the scheme meetings which took place at the offices of Linklaters LLP after a short preliminary session dealing with administrative matters has described carefully the process followed and the outcome of the voting.

55. Inevitably, the class meetings 3 and 4 were formalistic: the Chairman held proxies at each on behalf of all Scheme Creditors within the class and cast them in favour of the Scheme, thus resulting in 100% support in terms of both number and value.

56. The process at those meetings and the more contentious class meetings was entirely regular. I think the only matter I need mention before assessing the actual voting is that nine Higher Rate Creditors (participating in scheme meeting 2) exercised an entitlement pursuant to the Convening Order to submit Increased Voting Rights Requests on the basis that they should be entitled to voting rights greater than those calculated by applying an interest rate of 8% per annum. The Chairman’s Report records that in the exercise of his discretion he accepted all the requests and that of the nine, seven voted for the Scheme and two against.

Voting results at the class meetings

57. The voting results at the meetings for (1) 8% Creditors and Specified Interest Creditors (“the 8% Creditor Meeting”) and (2) Higher Rate Creditors (excluding the Senior Creditor Group, “the Higher Rate Creditor Meeting”) can be summarised as follows:

(1) At the 8% Creditor Meeting, the Scheme was approved by 129 out of the 132 votes cast, representing 97.7% in number and 96.3% in value of those voting. The turnout by reference to claim value at the 8% Creditor Meeting was equal to 96.1% of those

entitled to vote.

(2) At the Higher Rate Creditor Meeting, the Scheme was approved by 74 out of the 78 votes cast – representing 94.9% in number and 88.0% in value. The turnout by reference to claim value at the meeting was equal to 94.9% of those entitled to vote.

(3) Only 3 creditors (out of 130) voted against the Scheme at the 8% Creditor Meeting, and only 4 creditors (out of 77) – two of which are members of the same corporate group – voted against the Scheme at the Higher Rate Creditor Meeting.

(4) The Senior Creditor Group voted in a separate class from other 8% Creditors and Higher Rate Creditors. Accordingly, the voting figures for the 8% Meeting and the Higher Rate Meeting do not include claims held by the Senior Creditor Group.

(5) Those statutory majorities would have been obtained even if all of the Increased Voting Rights Requests had been rejected in their entirety or if only the Increased Voting Rights Requests made by the “no” voters were admitted.

(6) If the Wentworth Senior Creditors had been excluded from the 8% Creditor Meeting, the Scheme would still have been approved by 115 creditors, representing 97.5% in number and 93.7% in value.

(7) If the Wentworth Senior Creditors had been excluded from the Higher Rate Meeting, the Scheme would still have been approved by 62 creditors, representing 93.9% in number: but they would have represented only 62.2% in value (thus falling short of the statutory majority required of 75%).

58. These voting results, and a further analysis of the split between the votes of Wentworth entities in the two relevant classes and the votes of others, are summarised in the Table referred to above, as follows:

59. The two points made by Cleary Gottlieb as referred to above at paragraph [53] can be seen from that Table, being as follows (quoting their e-mail directly):

(1) “The votes referred to in the “Others” column of the table…includes votes that are controlled by entities that are part of the Wentworth Group and the Senior Creditor Group. Our client does not know the extent of the claims controlled by the Wentworth Group and Senior Creditor Group within the “Others” column.

(2) Recognising that the Judge has indicated that he is not minded to revisit class composition issues, if [the Higher Rate Creditors Meeting] had proceeded without claims held directly by the Wentworth Group (i.e. of the Wentworth Group votes are excluded from the votes at [that meeting]), then the scheme would not have obtained the required statutory majority by value [at that meeting]. All the more so if claims controlled but not directly held by the Wentworth Group and the Senior Creditor Group had been excluded.”

60. These were fair points, neatly made: and though, like other points of objection, they were not pursued in oral argument (GSI and Cleary Gottlieb having apparently taken the decision not to appear, though it was of course open to them to do so), they seem to me to be relevant at every stage of the assessment of the Scheme, including any review of the class composition issue. That is a convenient point to turn to the three-stage approach which the Court has become accustomed to adopting in determining whether to sanction a scheme.

Part F: the Court’s jurisdiction and principles as to its exercise

61. The relevant statutory provision is section 899 of the CA 2006 Act, which provides as follows:

“(1) If a majority in number representing 75% in value of the creditors or class of creditors or members or class of members present and voting either in person or by proxy at the meeting summoned under section 896, agree to any compromise or arrangement, the court may, on an application under this section, sanction the compromise or arrangement.

(2) An application under this section may be made by – (a) the company ...

(3) A compromise or arrangement sanctioned by the court is binding on – (a) all creditors or the class of creditors or on the members or a class of members ... and (b) the company ...”

62. The term ‘company’ in this context means any company liable to be wound up under the Insolvency Act 1986, including a foreign company which though unregistered under the Companies Act has a “sufficient connection” with England or Wales (see Re Rodenstock GmbH [2011] EWHC 1104 (Ch), [2012] BCC 459). LBIE, which was incorporated here, is plainly a qualifying ‘company’.

63. The term ‘creditor’ for the purposes of a scheme has a broader meaning than it has for the purposes of liquidation. For the purposes of the scheme jurisdiction, any person who has a monetary claim against the company that, when payable, will constitute a debt is a ‘creditor’; and it matters not whether that claim is actual, prospective or contingent: see Re Lehman Brothers International (Europe) (in administration) [2009] EWCA Civ 1161, [2010] BCLC 496 at [58]; and Re Midland Coal, Coke & Iron Co [1895] 1 Ch 267 at 277.

64. Similarly, the terms ‘compromise’ and ‘arrangement’ have been construed widely by the Courts: all really that is required is a sequence of steps involving some element of give and take, rather than merely surrender or forfeiture.

65. In Re Telewest Communications (No. 2) Ltd [2005] BCC 36, David Richards J explained the principles to be considered by the Court when deciding whether to sanction a scheme of arrangement (at [20]-[22]):

“The classic formulation of the principles which guide the court in considering whether to sanction a scheme was set out by Plowman J in Re National Bank Ltd [1966] 1 All ER 1006 at 1012, [1966] 1 WLR 819 at 829 by reference to a passage in Buckley on the Companies Acts (13th edn, 1957) p 409, which has been approved and applied by the courts on many subsequent occasions:

‘In exercising its power of sanction the court will see, first, that the provisions of the statute have been complied with; secondly, that the class was fairly represented by those who attended the meeting and that the statutory majority are acting bona fide and are not coercing the minority in order to promote interests adverse to those of the class whom they purport to represent, and thirdly, that the arrangement is such as an intelligent and honest man, a member of the class concerned and acting in respect of his interest, might reasonably approve. The court does not sit merely to see that the majority are acting bona fide and thereupon to register the decision of the meeting; but at the same time the court will be slow to differ from the meeting, unless either the class has not been properly consulted, or the meeting has not considered the matter with a view to the interests of the class which it is empowered to bind, or some blot is found in the scheme.’

This formulation in particular recognises and balances two important factors. First, in deciding to sanction a scheme under s 425 [the predecessor of section 899], which has the effect of binding members or creditors who have voted against the scheme or abstained as well as those who voted in its favour, the court must be satisfied that it is a fair scheme. It must be a scheme that ‘an intelligent and honest man, a member of the class concerned and acting in respect of his interest, might reasonably approve’. That test also makes clear that the scheme proposed need not be the only fair scheme or even, in the court’s view, the best scheme. Necessarily there may be reasonable differences of view on these issues. The second factor recognised by the above-cited passage is that in commercial matters members or creditors are much better judges of their own interests than the courts. Subject to the qualifications set out in the second paragraph, the court ‘will be slow to differ from the meeting’.”

66. The passage from Buckley quoted by David Richards J effectively

involves a three-stage test:

(1) At the first stage, the Court must consider whether the provisions of the statute have been complied with.

(2) At the second stage, the Court must consider whether the class was fairly represented by the meeting, and whether the majority are coercing the minority in order to promote interests adverse to those of the class whom they purport to represent.

(3) At the third stage, the Court must consider whether the scheme is one which a creditor might reasonably approve. If the scheme is one which a creditor could reasonably approve, it is said to be “fair”, even though the Court retains ultimate and unfettered discretion whether to sanction a scheme, and to withhold sanction if it considers there is nevertheless some overriding unfairness in the scheme or the manner in which it has been presented or notified and explained, or in the event that some ‘blot’ is found. Indeed, there is no entitlement to have a ‘fair’ scheme sanctioned: the exercise of its jurisdiction being discretionary, the Court is not obliged to sanction a scheme.

67. The breadth of its jurisdiction emphasises the care that must be taken by the Court in its exercise. In addition to satisfying itself as to the matters above, the Court must also be satisfied as to the adequacy and accuracy of the explanatory statement provided in respect of the scheme, and that its recipients have been afforded adequate time to consider their position and to give vitality to their right to object.

68. However, the most troublesome of the preconditions for the exercise of jurisdiction (in the sense of its propensity to give rise to difficult issues) is that the scheme must have been approved by the statutory majorities in value and number at class meetings in each case constituted by the Court and comprised only of

“those persons whose rights are not so dissimilar as to make it impossible for them to consult together with a view to their common interest”:

see Sovereign Life Assurance v Dodd [1892] 2 QB 573 at 583 (Bowen LJ) and Re UDL Holdings Ltd [2002] 1 HKC 172 at [27] (Lord Millett NPJ). The issue is a fundamental one: for the jurisdiction of the Court to enable a majority to bind the minority on the terms of a scheme is dependent on the correct identification and composition of classes, and the passing of resolutions by the statutory majorities at properly constituted class meetings convened and held in accordance with the Court’s directions: and see In re Apcoa (No. 2) at [45].

69. But also fundamental, at least to the modern approach, is to distinguish between the legal rights which the scheme creditors have against the company, and their separate commercial or other interests or motives (whether or not related to the exercise of such rights). As Lord Millett clarified in UDL at 184-5:

“The test is based on similarity or dissimilarity of legal rights against the company, not on similarity or dissimilarity of interests not derived from such legal rights. The fact that individuals may hold divergent views based on their own private interests not derived from their legal rights against the company is not a ground for calling separate meetings … The question is whether the rights which are to be released or varied under the scheme or the new rights which the scheme gives in their place are so different that the scheme must be treated as a compromise or arrangement with more than one class.”

70. Even then, a material difference in legal rights does not necessarily preclude their respective holders from being included in a single class: for the second part of the test enables that provided that they are not “so dissimilar as to make it impossible for them to consult together with a view to their common interest”. That, unusually and perhaps confusingly, introduces into a jurisdictional issue a subjective assessment, which may account for changing judicial perceptions over the years as to class constitution in the light of the developing and prevailing inclination of judges to recognise the dangers of giving a veto to a minority group by (in Lord Neuberger’s words in Re Anglo American Insurance Co Ltd [2001] 1 BCLC 755 at 764) being “too picky about different classes” and ending up “with virtually as many classes as there are members of a particular group.” Hence my statement in Re Primacom Holding GmbH [2013] BCC 201 at [44]-

[45]:

“… The golden thread of these authorities, as I see it, is to emphasise time and again … [that] in determining whether the constituent creditors’ rights in relation to the company are so dissimilar as to make it impossible for them to consult together with a view to their common interest the court must focus, and focus exclusively, on rights as distinct from interests. The essential requirement is that the class should be comprised only of persons whose rights in terms of their existing and the rights offered in replacement, in each case against the company, are sufficiently similar to enable them to properly consult and identify their true interests together.

I emphasise this point because it … enables the court to take a far more robust view as to what the classes should be and to determine a far less fragmented structure than if interests were taken into account.”

71. In parallel with this development of the Court’s approach to this issue of jurisdiction, the Court has also changed its practice and accepted that the identification of proper class composition is one to be addressed at the time of the Convening Hearing. Prior to Re Hawk Insurance Company Ltd [2002] BCC 300 the Court had declined to engage with the issue until the final (sanction) hearing, leaving it to the proponents of the scheme to live with their choices until the potential sudden death of disapproval at the final hurdle.

72. The purpose of the change of practice introduced pursuant to the observations of Chadwick LJ in Re Hawk, and now embodied in the Practice Statement, was and remains to accelerate to the first stage (at the Convening Hearing) consideration by the Court of the issue of class composition. Whilst the Court’s decision at that stage is not final, the applicant has a legitimate expectation that, unless circumstances materially alter or fresh considerations are put before it which the Court accepts should be addressed, the Court will not of its own motion change its mind, since (as I put it in In re APCOA Parking Holdings GmbH (No.2) “to do so would subvert the purpose of the revised practice”: and see also In re Hawk itself at [21] and Re Global Garden Pructs Italy SpA [2017] BCC 637, [2016] EWHC 1884 (Ch) at [43].

73. In the present case, there was substantial opposition to the proposals for class composition put forward by the Administrators at the Convening Hearing (which lasted two days). As I have said, three creditors each represented by Counsel put forward arguments why the proposals should be rejected. I sought to describe the arguments then advanced, and my assessment and adjudication of them, in an oral judgment given after time for consideration. As appears from that judgment, the focus at that stage was on (a) whether all the Wentworth entities, including the entity holding the Sub-Debt, should be seen as one, so that the proposal simply to establish a separate class meeting for the Sub-Debt entity did not really or sufficiently address the problem, on the principal basis, as Mr Twigger put it on behalf of Deutsche, of its suggested “failure to recognise that the benefits to be obtained from the Scheme by some of the Wentworth Parties with a view to their being shared among the Wentworth Parties as a whole means that none of the Wentworth Parties can consult with the independent Higher Rate Creditors who do not stand to receive those benefits”; and/or more particularly, (b) whether the right negotiated by the Wentworth Sub-Debt entity to be consulted in respect of the certification and adjudication process was a right shared (at least in economic or commercial terms) by all Wentworth entities so as to place them all in a different class from others; and (c) whether (as Marble Ridge submitted) there was a requirement for a separate class of creditors (like itself) which had acquired rights under a ISDA Master Agreement from a now insolvent entity which in consequence had especial difficulties in certifying its claim to interest, and thus was disadvantaged in and by the adjudication process. For reasons I sought to summarise, I did not consider any of these arguments justified rejection of the proposed class composition.

74. I had envisaged that there might be further evidence or reason adduced at the Sanction Hearing in support of the over-arching proposition that all the Wentworth entities were to be regarded in law as one: but that did not eventuate. As already stated, in point of fact, both CRC and Marble Ridge in the end supported and voted in favour of the Scheme, and Deutsche withdrew its objection (having all obtained some improvements to the adjudication process).

75. Thus, the reference in Cleary Gottlieb’s letter (to which I have referred in paragraph [53] above, and which was sent to the Administrators but produced to the Court at Cleary Gottlieb’s request during the Sanction Hearing), to my indication that I was not minded to revisit class composition issues at the hearing should be viewed in the light of the considerable exploration of the issue at the Convening Hearing, my outline judgment following it, and the fact that no further submissions were sought to be made to me by objectors.

76. However, I should perhaps make clear that, whilst I did not encourage further submissions on the point from proponents and supporters of the Scheme, I have nevertheless reviewed the issue precisely because it goes to jurisdiction, and also because I accept that in this case the question of class composition has not been straightforward.

77. I have been concerned especially to re-satisfy myself in respect of five features of the Scheme and its context, even though some were not the subject of objection at any stage: (a) the close association between the Wentworth companies; (b) the entitlement to consultation in some aspects of the adjudication process which the Wentworth Subordinated Creditor has obtained in the process of the Scheme’s development; (c) the Lock-Up Agreement; (d) the consent fee payable by Wentworth Group companies to the Senior Creditor Group; and (e) the fact that some provable debts though not legally owned by the Senior Creditor Group are or may be ultimately controlled by it.

78. As to (a) in paragraph [77] above, it appears to be obvious that the Wentworth Group companies are very closely associated, and likely that in economic terms, unlike other creditors, they have, as a group, legal rights and commercial interests as subordinated creditors which mean that what they lose as Higher Rate Interest creditors they stand to gain in that other capacity. The question I have had to consider is whether that introduces a difference of class rights; and, for example, whether I should take each Wentworth Group entity as having, for the purposes of class composition, cross-holdings and/or the legal rights enjoyed by each other, or another, Wentworth Group entity so as should have been taken to require all such entities to vote in a class separate to other creditors. I remain satisfied that it does not. It might have been different had evidence been advanced such as to persuade me that the Wentworth Group entities were not merely connected but in law each alter egos of the other; but it was not. Further, by analogy, cross-holdings (where a member of one class is also, in respect of another legal right, a member of another class) does not, of itself at least, fracture the class composition: see Re Telewest, UDL Holdings and also Re Primacom.

79. Similarly, as to (b) in paragraph [77] above, I also remain of the view that the fact that the Wentworth Group entity holding the Sub-Debt (which itself has no other claims), has (apparently as a condition of its support for the Scheme) negotiated to have various powers under the Scheme in relation to the adjudication process, does not raise a class issue (beyond the fact that it has been required to vote in a class of its own). In the event, I should note, these powers have been modified since the Convening Hearing to remove aspects of them which have caused especial concern to objectors: in particular, the final form of the Scheme no longer allows the Subordinated Creditor to determine the amount of any counter-offer by LBIE. This was the only real objection that the opposing creditors identified at the Convening Hearing, and it has now been removed. In any event, and as submitted by the Administrators:

(1) To the extent that any of the Wentworth Senior Creditors is an 8% Creditor, a Specified Interest Creditor or a Higher Rate Creditor, the rights given to them under the Scheme (in their capacity as such) are precisely the same as the rights given to other creditors.

(2) Even if the Wentworth Senior Creditors were motivated to exercise their voting rights as 8% Creditors, Specified Interest Creditors or Higher Rate Creditors in order to enhance the recovery of the Sub-Debt, that is a classic example of a point that may go to fairness, rather than class composition.

(3) In the absence of a relevant difference between the legal rights of the Wentworth Senior Creditors (qua 8% Creditors, Specified Interest Creditors or Higher Rate Creditors) and the legal rights of other creditors in those classes, the question of whether those creditors can “consult together with a view to their common interest” does not arise. As explained above, there is no relevant difference in rights.

80. As to (c) in paragraph [77] above, one aspect of the Lock-Up Agreement, which was advanced (if at all) only tangentially at the Convening Hearing, has since then caused me some further pause for thought. This is whether the fact that the Wentworth Group, as well as the Senior Creditor Group, have agreed not only to support the Scheme but also to accept the Settlement Premium in respect of all Higher Rate Claims (rather than seeking to certify their cost of funding) signifies or entails that their rights as against the company now are different from those of other Higher Rate Creditors, and could be said to make it impossible for them to “consult together with a view to their common interest” (the basic principle as classically stated by Bowen LJ in Sovereign Life Assurance v Dodd [1892] 2 QB 573 at 583) since they no longer can participate in the adjudication process, and thus have no interest in it or in discussing it. I have added to my consideration of this point the potentially linked fact of the agreement between Wentworth Group and the Senior Creditor Group (but not the Administrators or LBIE) for the payment by Wentworth Group companies of a fee of £35 million. I have concluded, however, that these matters do not unsettle the class composition, principally because the Lock-Up Agreement does not, on my analysis, remove the common rights of all the Higher Rate Creditors, but simply commits Wentworth Group as to which of two ways of exercising that right it will choose. In my view, the fact of the agreement in advance as to which of two options offered under the Scheme in respect of the right to select does not signify any material divergence of relevant right, any more than a firm internal and unexpressed election on its part (such as all such Higher Rate Creditors had to make before voting), without binding commitment or agreement, would do so. Furthermore, I do not consider that this precontracted choice is such as to prevent constructive discussion of the overall Scheme and the balance of benefit that it is intended to bring; and that is so taking into account the arrangements between Wentworth Group and the Senior Creditor Group. Whilst I accept all this is relevant to stages two and three of the three-stage test originally formulated in Buckley on the Companies Acts (13th edn, 1957) and approved by David Richards J (as he then was) in Re Telewest Communications (No. 2) Ltd I was satisfied that it does not cast doubt on the composition of the classes convened.

81. I need add little more to what I have already said about the consent fee (see (d) in paragraph [77] above). In the end, the point was pursued principally in correspondence on behalf of GSI and was presented clearly and sharply as follows in a letter dated 8 June 2018 from Cleary Gottlieb to the Administrators’ solicitors (Linklaters LLP), as follows: