Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

England and Wales High Court (Administrative Court) Decisions

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> England and Wales High Court (Administrative Court) Decisions >> River Action UK, R (On the Application Of) v The Environment Agency [2024] EWHC 1279 (Admin) (24 May 2024)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Admin/2024/1279.html

Cite as: [2025] PTSR 240, [2024] WLR(D) 244, [2024] EWHC 1279 (Admin)

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [Buy ICLR report: [2025] PTSR 240] [View ICLR summary: [2024] WLR(D) 244] [Help]

KING'S BENCH DIVISION

ADMINISTRATIVE COURT

2 Park Street, Cardiff, CF10 1ET |

||

B e f o r e :

____________________

| The King (on the application of RIVER ACTION UK) |

Claimant |

|

| - and - |

||

| THE ENVIRONMENT AGENCY |

Defendant |

|

| -and- |

||

| SECRETARY OF STATE FOR ENVIRONMENT, FOOD AND RURAL AFFAIRS |

Interested Party |

|

| -and- |

||

| NATIONAL FARMERS UNION |

Intervenor |

____________________

Mr Charles Streeten (instructed by Environment Agency Legal Department) for the Defendant

Mr Ned Westaway (instructed by the GLD) for the Interested Party

Mr Hugh Mercer KC and Ms Naomi Hart (instructed by the National Farmers' Union) for the Intervener

Hearing dates: 7th & 8th February 2024

____________________

Crown Copyright ©

- The claimant is a UK-based environmental charity which is committed to addressing the problem of river pollution, in particular that which is caused by agricultural and food production practices and the discharge of sewerage by water companies. Since 2021 the claimant has been campaigning to draw attention to the pollution of the River Wye ("the Wye"), specifically targeting the activities of the intensive livestock industry. The defendant is the agency who have specific responsibilities for environmental regulation, and in the context of this case are charged with responsibility for enforcing the Reduction and Prevention of Agricultural Diffuse Pollution (England) Regulations 2018 ("the 2018 Regulations"). The interested party are the government department who sponsored and developed the 2018 Regulations. The intervenor is an Employers' Association pursuant to the Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992, and its objects include representing and promoting the interests of farmers and growers. The intervenor was permitted to intervene solely on the question of the interpretation of Regulation 4 of the 2018 Regulations.

- This claim for judicial review is brought by the claimant on three grounds. The first two are interrelated. The claimant challenges the legality of the approach of the defendant to the enforcement of the 2018 Regulations, both in terms of the enforcement action taken by the defendant and also the role of the Statutory Guidance published by the interested party pursuant to the 2018 Regulations for the purpose of guiding the defendant's enforcement activity. The third of the claimant's grounds alleges a breach of regulation 9(3) of The Conservation of Habitats and Species Regulations 2017 ("the Habitats Regulations"). In relation to that ground, it is alleged that the defendant has failed to have regard to the requirements of the Habitats Regulations in undertaking its enforcement activity.

- I repeat the thanks to all the legal teams involved in this case which I expressed in court. A great deal of thought went into the preparation of the papers for the hearing, and in particular the preparation of a helpful core bundle. The written and oral submissions which the court received were of high quality, and the focussed advocacy of those appearing in the case enabled us to have an efficient and effective hearing. I am very grateful for all the parties' hard work.

- The Wye, along with the River Lugg, have wide catchment areas within the borderlands between England and Wales. Both rivers are areas of special importance for nature conservation and are designated as Sites of Special Scientific Interest. The lower reaches of the River Lugg along with the Wye are also part of the River Wye Special Area of Conservation (SAC) which was originally designated under the European Community Habitats Directive. The Wye is also a valuable recreational resource, providing the opportunity for tourism and outdoor pursuits such as fishing and kayaking. The catchment supports a significant number of agricultural and, in particular, livestock enterprises including a large number of intensive poultry units.

- In recent years the Wye has been the subject of extensive pollution in the form of high concentrations of phosphorus in the river's water. The consequences of this include the development within the river of substantial algal blooms, turning the river green, interfering with its ecology and leading to an impact upon key species, such as ranunculus or the water crowfoot family of plants, the presence of which justified the original designation of the Wye as an SAC. The evidence also suggests that the effect of the algal blooms also impacts upon the recreational and tourist use of the river.

- There is no dispute in this case that there are water quality issues in the Wye related to phosphate limits being exceeded within the catchment. This was documented in November 2021 in the "River Wye SAC Nutrient Management Plan Phosphate Action Plan", published by the defendant, along with Natural Resources Wales and Natural England. The document identifies point sources of phosphorus pollution, such as water treatment works, and the actions being taken to address reducing their contribution to the levels of phosphorus in the Wye. The document also identifies the issue, which is of central concern in these proceedings, of diffuse phosphate sources. By diffuse sources, what is meant is multiple sources, in contrast to point sources, the contribution of each of which may be small but cumulatively they may have a significant effect in aggregate. The document noted that modelling indicated that most of the diffuse phosphate load in the catchment arose from agriculture.

- In a subsequent study, entitled "Re-Focusing Phosphorus use in the Wye Catchment: RePhoKUs", co-ordinated by academics at the University of Lancaster and the University of Leeds, it was estimated that, following the improvements in relation to phosphate emissions from water treatment works, some 60 to 70% of the total phosphate load in the catchment came from agricultural sources. The following extracts from the summary of the key findings of this study provide a distillation of the issues facing the conservation of the Wye and the need for the action which is the subject matter of this case.

- "The Wye catchment has a high risk of agricultural P loss due to high P input pressure, poorly-buffered and highly dispersible P-rich soils, steep slops and moderate to high rainfall.

- Farming generates an annual P surplus (i.e. unused P) of ca.3000 t (17kg P ha-1) in the Wye catchment, which is accumulating in the agricultural soils. This P surplus is nearly 60% greater than the national average, and is driven by the large amounts of livestock manure produced in the catchment.

- The risk of P loss in land runoff due to accumulation of soil is greater in the Wye catchment than in other UK soils due to poor soil P buffering capacity and high dispersibility during storm events.

- Water quality in the Wye catchment, and many other livestock-dominated catchments, will not greatly improve without reducing the agricultural P surplus and drawing down P rich soils to at least the agronomic optimum. This will take many years.

- A combination of reducing the number of livestock and processing of livestock manures to recover renewable fertilisers that can substitute for imported P products is needed to effectively reduce the P surplus."

- The genesis of the 2018 Regulations, which are also known as the Farming Rules for Water, is that they were part of a broader initiative to meet the requirements of The Water Framework Directive, which itself included requirements to address the control of diffuse pollution. The 2018 Regulations apply to the whole of England, not simply the Wye, but given the issues set out above they are of importance to the control of pollution in the Wye. The background to this legislation, as explained in the documentation and the witness statement of Mr Adnan Obaidullah on behalf of the interested party, is that agriculture was identified as the single largest source of water pollution in England both at the time when the 2018 Regulations were introduced and now. Whilst the detail varies from catchment to catchment, it is estimated that nationally agricultural activities are responsible for 50% of nitrate pollution, 25% of phosphorus pollution and 75% of sediment pollution.

- Work on the preparation of the 2018 Regulations commenced in early 2013. In September 2015 the interested party published a consultation in relation to new basic rules to tackle diffuse water pollution from agriculture. The consultation explained that the impact of diffuse water pollution included eutrophication, increased flood risk, the silting of fish spawning grounds, as well as pollution of bathing waters. There were advantages for farm businesses in the form of increasing the productivity and the resource efficiency of farms, as well as building a strong reputation for environmental standards in England. The basic rules which were proposed were said to reflect good practice already set out in the interested party's Code of Agricultural Good Practice. Option 1 comprised seven rules, including at rule 2 that the land manager should use a fertiliser recommendation system taking into account soil reserves and organic manure supply, thereby reducing "diffuse pollution to surface water and groundwater by planning crop nutrient requirements and spreading no more inorganic and organic fertilisers than a crop (including grass) needs."

- Option 2 contained a further four rules in addition to Option 1. These additional rules included rule 8, which required that the land manager "not spread more than 30m3/ha of slurry or digestate or more than 8t/ha of poultry manure in a single application between 15th October and the end of February" with no repeat spreading for 21 days. This was intended to reduce diffuse pollution through surface runoff and leaching by not spreading large amounts of fertiliser during the time of year when the risk of pollution is greatest and plant requirement least. There would be expected to be less uptake by crop of nutrients over the winter months. Rule 9 precluded the spreading of manufactured fertiliser or manures at high-risk times or in high-risk areas. By this was meant avoiding "weather and soil conditions (eg high rainfall or frozen ground) which favours quick transfer to surface runoff or drains, or when crops cannot take up nutrients".

- The consultation contained information about the approach which was to be taken to enforcement of the new rules. At paragraph 3.7 the consultation document provided as follows:

- In November 2017 the interested party reported the response to the consultation. As a result of the consultation exercise there were now proposed to be eight rules, including in particular the following:

- In February 2018 the interested party published an Impact Assessment in relation to the proposal to introduce secondary legislation. This document explained that as a result of market failure there were limited incentives for farming businesses to adopt practices which would reduce water pollution, and that effectively tackling water pollution required a mix of regulation, voluntary action and financial incentives. The measure was also required in order to meet the objectives of the Water Framework Directive: "there is evidence of widespread agricultural diffuse pollution by phosphorus but no mandatory controls in place to tackle it". Whilst some farmers had responded to the need to take steps on a voluntary basis, it was concluded that it was now necessary to engage with the farmers who had not responded to these voluntary approaches. The policy objective was identified as being to establish a basic standard of mandatory good practice through the introduction of rules which met the requirements of the Water Framework Directive "without gold-plating".

- To assess the impact of the proposed new legislation the document set out the three options which had been considered. The first option was to do nothing, and it was rejected because it would not meet the requirements of the Water Framework Directive. The document noted the two options that had been the subject of consultation and concluded that the option which was being proposed was "a proportionate, risk-based approach to tackling diffuse pollution in a way that minimises burdens to farmers". The final preferred option comprised eight rules, five of which were with reference to organic manures and manufactured fertiliser planning, storage and application. The other three rules were related to soil management. The first five rules, dedicated to the planning, storage and application of organic manures and manufactured fertiliser, were framed in the following terms:

- The impact assessment went on to record that this final preferred option was anticipated to achieve a 4.6% reduction in phosphorus arising from diffuse agricultural pollution. It was recognised that the introduction of the rules would give rise to costs for some farmers, in particular if they did not have sufficient slurry storage available to them and had to undertake capital expenditure to increase their storage capacity. The impact assessment concluded that there was a trade-off between the cost to business and the need to achieve good status under the Water Framework Directive and that what was proposed was regarded by the interested party's lawyers as the minimum required for basic measures.

- In March 2018 the interested party published a policy paper in relation to the proposed Farming Rules for Water. The paper set out the approach which it was intended would be taken to enforcement, emphasising that they would be introduced through an "advice-led approach", in which it would be for the defendant to provide advice on how to comply with the new legislation and help farmers to understand it. Enforcement was proposed to be proportionate, with an emphasis on working with farmers to ensure that they were brought into compliance. The majority of cases would be dealt with by the provision of advice and if necessary civil sanctions, with prosecution being reserved for cases in which other approaches to enforcement had been unsuccessful. The section of the paper devoted to managing compliance contains the following observations:

- The preparation described above gave rise to the enactment of the 2018 Regulations, which were designed to give legislative effect to the Farming Rules for Water which had been the subject of consultation and refinement by the interested party. Regulation 2 of the 2018 Regulations contains a number of definitions of terms to assist in the operation of the Regulations. In particular the term "agricultural diffuse pollution" is defined as follows:

- Regulation 2(2) assists with the term "application" as it used in the context of the Regulations and provides as follows:

- At regulation 2(3) a definition of "leaching" is provided, identifying that it "means the process by which agricultural pollutants are washed or drained from soil into inland freshwaters or coastal waters, or into a spring, well or borehole, by rainwater or other liquid applied to agricultural land".

- Regulation 3 prohibits the application of either organic manure or manufactured fertiliser to agricultural land if the soil is waterlogged, flooded or snow covered, or where the soil has been frozen for more than 12 hours in the previous 24 hours. Regulation 4 is the regulation which is central to these proceedings, and which addresses the application of organic manure and manufactured fertiliser to agricultural land. It provides as follows:

- The provisions of Regulation 4 are supplemented by Regulation 5 which provides as follows:

- Regulations 6, 7 and 8 deal with the question of application of manufactured fertilisers and organic manure in proximity to a spring, well or borehole, in-land freshwaters or coastal waters. Regulation 9 deals with the storage of organic manure and regulation 10 addresses issues related to the management of livestock and soil. Regulation 11(1) creates a criminal offence of failing to comply with the requirements of Regulations 3 to 10, and by Regulation 11(2) the penalty for a person found guilty of this offence to be liable to an unlimited fine. Regulation 12 creates a defence for a person who is able to show that they "took all reasonable steps and exercised all due diligence to avoid committing the offence". Regulation 13 creates the possibility of imposing various civil sanctions in relation to an offence. Finally, Regulations 14 and 15 deal with enforcement and the roles of the defendant and the interested party as follows:

- The interested party, in accordance with Regulation 15 of the 2018 Regulations, published Statutory Guidance entitled "Applying the Farming Rules for Water" ("the Statutory Guidance") on 30th March 2022, and updated its text on 16th June 2022. It commences by noting that the defendant's approach will generally be to prioritise the provision of advice and guidance before taking enforcement action. If advice and guidance do not achieve the necessary changes in behaviour, then the defendant will escalate matters and impose either civil or criminal sanctions. The Statutory Guidance then proceeds to set out criteria that the defendant "should consider" when undertaking an inspection in relation to the 2018 Regulations, and states that "[e]nforcement action should not normally be taken where land managers have met the criteria".

- The criteria commence with the observation that land managers will need to demonstrate that they have planned applications in accordance with the Farming Rules for Water and that plans should:

- show an assessment of the crop nutrient requirement for each cultivated land parcel that should be informed by one of the following:

- a manual such as AHDB's nutrient management guide (RB209) (https://ahdb.org.uk/nutrient-management-guide-rb209)

- farm software such as PLANET or nutrient management tools such as those provided by Tried and Tested

- a suitably qualified professional, such as an agronomist or FACTS advisor

- take account of the results of soil sampling and analysis

- take account of the nutrient content of the applied organic manures and manufactured fertilisers."

- Section 2.2 of the Statutory Guidance contains material in relation to the assessment of crop and soil need when undertaking the planning required. This section provides in detail as follows:

- it is not reasonably practicable to do so they have taken all appropriate reasonable precautions to help mitigate against the risk of diffuse agricultural pollution

- produces and applies its own organic manure to its own land and cannot reasonably take measures to treat or manage the manure (for example, if it exports it) to avoid applications that risk raising the soil P index level of soil above crop and soil need target levels over a crop rotation

- imports organic manure as part of an integrated organic and manufactured fertiliser system and cannot reasonably import organic manures that would not risk raising the soil P index level of the soil above crop and soil need target levels over a crop rotation." (Emphasis added)

- The Statutory Guidance goes on to deal with specific details in relation to the assessment of whether there is a significant risk of agricultural diffuse pollution due to nitrate leaching depending upon the readily available nitrogen content of organic manures. The Statutory Guidance sets out application rate limits for different time periods within the calendar year depending upon the soil type of the land on which the application is going to be made. The Statutory Guidance also sets out matters to be assessed in deciding whether reasonable precautions have been taken to prevent agricultural diffuse pollution.

- As set out above, the Wye is an SAC, designated originally under the Habitats Directive, which at article 6(2) provides :

- The provisions of the Habitats Directive were transposed into domestic legislation most recently in 2017 in the provisions of the Habitats Regulations. Following the departure of the UK from the EU, the Conservation of Habitats and Species (Amendment) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019 inserted Regulation 3A into the Habitats Regulations to ensure the continued application of the substance of the Habitats Directive in the UK. Regulation 16A was also inserted so as to ensure the continuation of the duty upon the interested party, as the "appropriate authority" for the purposes of the Habitats Regulations, to ensure the achievement of the management objectives of the national site network. This duty includes maintaining (or where appropriate restoring) protected habitats like the Wye at favourable conservation status.

- It is common ground that for the purposes of the Habitats Regulations the defendant is a "competent authority". The requirement that the defendant is under given this status is set out in Regulation 9(3) of the Habitats Regulations in the following terms:

- The content of this duty under Regulation 9(3) of the Habitats Regulations was recently considered in the case of R (Harris) v Environment Agency [2022] PTSR 1751; [2022] EWHC 2264 (Admin). This case concerned a review of the grant of licences for the abstraction of water by the defendant which might affect Sites of Special Scientific Interest in the Norfolk Broads. Initially the defendant was required by Regulation 50 of the Conservation (Natural Habitats etc) Regulations 1994 (the predecessor of the Habitats Regulations) to review all licences for the abstraction of water granted prior to 30 October 1994. The review identified the need for revision to some abstraction licences. The defendant also undertook an investigation as part of the "Restoring Sustainable Abstraction" ("RSA") programme to identify, investigate and resolve environmental damage caused by unsustainable water abstraction.

- In 2018 Natural England produced a site improvement plan for the Broads SAC and advised the defendant that there was a need to investigate where abstraction was having an impact on a particular site and examine whether there was a need to review abstraction licences as a consequence. The defendant decided to limit the RSA investigation to the impact of 240 licences on three Sites of Special Scientific Interest in the Broads SAC, notwithstanding that the modelling undertaken for the investigation showed that there were risks to other sites within the SAC beyond those Sites of Special Scientific Interest.

- The claimants sought judicial review of the decision to limit the RSA investigation to these three sites on the basis that to do so was a breach of the defendant's duty under Regulation 9(3) of the Habitats Regulations. Johnson J found for the claimants. He provided as follows in relation to the scope and nature of the duty under Regulation 9(3) of the Habitats Regulations and how it applied in that case:

- Johnson J went on to analyse the application of the duty in the context of this particular case, and specifically with respect to permanent abstraction licences, in the following terms, leading to the conclusion that the defendant was in breach of the duty under Regulation 9(3) of the Habitats Regulations and Article 6(2) of the Habitats Directive:

- As will become apparent below, underlying these proceedings is a disagreement in relation to the correct interpretation of Regulation 4 of the 2018 Regulations. The interpretation supported by the claimant and the defendant is not favoured by the interested party or the intervenor. In support of their various submissions on the topic of the correct interpretation of the 2018 Regulations evidence was provided to the court bearing upon the practical issues surrounding the timing of the application of the various forms of fertiliser to agricultural land.

- In essence, the view of the claimant and the defendant is that the phrase "the needs of the soil and crop on that land" in Regulation 4(1)(a)(i) of the 2018 Regulations should be interpreted as meaning the soil and crop on the land at the time of the application. The view of the interested party and the intervenor is that these words should be interpreted as allowing farmers to plan their nutrient applications in the light of soil and crop needs beyond immediate needs, such as over an annual crop cycle or a crop rotation, rather than the immediate needs of the soil and crop at the time when the application of manure or fertiliser is made.

- The particular interest of the intervenor is that the interpretation favoured by the claimant and the defendant is in their view unworkable and impractical. The intervenor contends that there would be serious implications for farmers if they are not permitted to carry out autumn spreading of manures on the basis of soil and crop needs being immediate as opposed to with respect to some crop in the future. The intervenor relies upon evidence in the form of an impact assessment from the Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board ("AHDB") published in June 2021 dealing with the effects of the Farming Rules for Water. This study examined the implications of the claimant and defendant's interpretation of Regulation 4(1)(a)(i) of the 2018 Regulations and, in effect, the inability of farmers to apply the various kinds of manure and fertiliser in the autumn, and requiring that the focus of applications of these materials be in the spring.

- The AHDB report concentrates on the implications for farm practice of the claimant and defendant's interpretation of the Regulations. The report notes that there would be an increased requirement for storage of organic materials, both in terms of temporary field heaps and also the length of time that they would be in place. This would increase the risk of them becoming a point source of pollution. There would also be an increased requirement for storage in terms of the provision of extra slurry storage tanks or lagoons.

- The report explains that whilst manufactured fertilisers can be top spread in the spring with comparatively light machinery, by contrast organic materials in the form of solid manures or slurry require heavier machinery for them to be applied and therefore there is a need to ensure that the soils to which they are to be applied are in a condition strong enough to support the weight of this machinery so as to avoid causing significant compaction. The conclusions of the report in this connection are as follows:

- The report undertook modelling work in relation to the effects of the impact of the claimant and the defendant's interpretation of the 2018 Regulations and concluded that as a consequence of limiting the autumn application of fertilisers and the use of current farm manure application practices there would be an increase in loss of nitrogen through ammonia volatilisation to the atmosphere, as well as an increase in phosphorus loss to water. The report considers possible changes to farm practices, but does not support either of the options it considers, namely restricting applications to the spring or the out-wintering of livestock to reduce the amount of managed manure. The report also considers the opportunities represented by slurry separation, composting and incineration as alternative means of treating organic manures.

- The report sets out a risk-based matrix to assist with the timing of application of fertilisers, factoring in matters such as the soil type concerned, the time of year and the nature of the crop to arrive at an understanding of the level of risk of applications at particular times. The report concludes as follows:

- reduce nitrate leaching losses by c.60% (1.5% decrease in the total loss from agriculture)

- increase in ammonia emission by c.10% (2% increase in total emissions from agriculture)

- increase in P loss by c.30% (5% increase in the total loss from agriculture)

- increase solid manure storage requirement by 7 million tonnes and slurry by 3million m3

- The AHDB report underpins the expert evidence relied upon by the intervenor produced by Mr John Rhys Williams, an expert in the field of soil science and agriculture. In his report he explains that there are three steps to effective nutrient management planning. The first step is to assess the soil nutrient supply and pH, which can be undertaken in accordance with the AHBD's Nutrient Management Guide (RB209) and its field assessment method, or by soil analysis and the taking of samples.

- The second step is to quantify the nutrient supply from organic materials, starting with the quantification of the manure nutrient content in the material to be applied. It is also necessary as part of the second step to minimise nitrogen losses, noting that application timing "is key to minimising nitrate leaching losses with autumn applications of high readily available N manures (e.g. poultry manure, slurry and digestate) likely to increase the risk of losses".

- The report notes the legislation in relation to Nitrate Vulnerable Zones restricts the timing of application of high readily available nitrogen manures to reduce nitrate leaching. The report also notes that "the risks of phosphorus and ammonium losses to water can be significant following applications of slurry and digestate to wet soils in spring as the potential for the contamination of drain flow and surface runoff is likely to be greater than following application to dry soils in the autumn". Mr Rhys Williams further observes, in line with the AHDB report, the differences in applying manufactured fertiliser and organic manures and the need to ensure that soils are strong enough to withstand the heavier machinery involved in the application of solid and liquid manures. Mr Rhys Williams draws attention to the risk-based matrix in the ADHB report which is referred to above.

- The third element of this second stage of the planning process is the estimation of crop available N supply, in relation to which it is noted that technical advice and guidance exists to determine the crop available supply of nitrogen from the manure type application method, delay between application and soil incorporation, soil type, excess rainfall and the contribution from mineralisation of organic nitrogen.

- The third and final stage of the process is the calculation of the fertiliser requirement, which will vary depending upon soil nitrogen supply, crop type and weather. Mr Rhys Williams concludes by observing that nutrient management planning ensures that nutrient applications from organic materials and manufactured fertilisers meet the requirements for optimal crop production to minimise cost and the risks of nutrient losses to the environment. The conclusions are summarised as follows:

- The claimant responds to this material with its own evidence to support the proposition that their interpretation of Regulation 4(1)(a)(i) of the 2018 Regulations is neither unworkable nor impractical. In his third witness statement Mr Charles Watson notes that, as recorded in the RePHoKUs report, there are parts of the country, like parts of East Anglia, in which there is a deficit of soil nutrients and a need to import large quantities of synthetic fertiliser to support their crops. Mr Watson alludes to a number of technical solutions which have been developed to enable the transfer of nutrients from areas such as the Wye catchment to areas where there is a deficit. He draws attention to an example of a food processor who operates 120 intensive poultry farms in the Wye catchment and who has commenced exporting its manure having treated it out of the catchment and selling it as a phosphorus-rich fertiliser in areas in which it is required. Mr Watson cites other examples of agricultural logistics operators and individual farmers supporting initiatives to export chicken litter and manures out of the catchment and to areas which require it as fertiliser.

- The claimant also relies upon the evidence of Mr Ben Taylor-Davies who is a farmer and agricultural consultant based in the Wye catchment. Mr Taylor-Davies explains that manure can be spread in the spring onto a crop that was sown in the autumn with little or no detriment to the crop. Mr Taylor-Davies also explains that he considers the intervenor's concerns about soil compaction as a result of spring applications of organic manures to be overstated, as on his own farm and in private trials of which he is aware there have been no yield losses from travelling over a crop in the spring. He therefore considers that "whilst applying manure in the spring when a winter sown crop needs the fertility may mean that farmers have to modify their practices, which some may be reluctant to do, I entirely reject the suggestion that it is not practicable to do so."

- The claimant has submitted evidence from another farmer, Mr John Turner, who explains that on his Lincolnshire farm he operates a Manure Management Plan and a Soil Management plan as his farming business is covered by certification as "organic" and also operates under the "Red Tractor Farm Assurance" scheme. The plans allow Mr Turner to establish in advance how the fertility of his soil will be managed, including the consideration of the application rate of manure based upon soil measurements and laboratory analysis.

- Mr Turner explains how the manure from the sheds in which his cattle are housed over the winter is removed every six weeks and stored. The manure is composted between April and July and following composting is in a more stable form than fresh manure. In his witness statement he explains how his farm operates in relation to the application of manure in the autumn and spring as follows:

- Mr Turner goes on to describe how grant funding for slurry management has been provided through the Rural Payments Agency to assist in the provision of future- proofed slurry infrastructure. Mr Turner also describes the opportunities for slurry processing and draws attention to the experience in the Netherlands of pig and poultry waste being transported out of the area of production to other areas in which it can be utilised. Mr Turner goes on to identify a number of available mitigation techniques such as the use of low-ground pressure application machinery and the availability of equipment to process slurries and manures so as to allow them to be transported to where they can be effectively deployed so as to minimise levels of pollution. In short, Mr Turners, overriding conclusion, is that it is entirely possible to farm with livestock without creating volumes of slurry or manure which cannot be responsibly managed and as a result of that management avoid the negative consequences of pollution.

- Against the background of evidence produced by the claimant, the claimant contends that the intervener has not come close to demonstrating that the claimant's interpretation of a Regulation 4(1)(a)(i) is either unworkable or impractical. The claimant relies upon this material in support of the construction which it places on regulation 4(1)(a)(i).

- The evidence in relation to the actions of the defendant in respect of the issue of diffuse agricultural phosphorus pollution of the Wye can be broadly categorised into three themes. Firstly, there is evidence in relation to the policies of the defendant bearing upon how it deploys its enforcement powers and the strategic approach which its policies set out as the context of enforcement. Secondly, the defendant has produced evidence in relation to specific examples of enforcement activity to show how the policy approach plays out in practice and on the ground. This material is subject to detailed criticism by the claimant, who submits that the evidence does not demonstrate a robust and lawful approach to the enforcement of the 2018 Regulations. Thirdly, there is evidence in relation to the actions relied upon by the defendant to demonstrate that they are complying with the duty under Regulation 9(3) of the Habitats Regulations, and addressing the decline in the nature conservation status of the Wye and the SAC.

- Commencing with the first theme in relation to the actions of the defendant, the background to the exercise of the defendant's powers of enforcement is provided by the Legislative and Regulatory Reform Act 2006. The defendant is an agency which is subject to the principles set out in section 21(2) of the 2006 Act which provide as follows:

- Pursuant to section 22 of the 2006 Act ministers have power to issue, and from time to time revise, a code of practice in relation to the exercise of regulatory functions.

- The defendant publishes its own "Environment Agency Enforcement and Sanctions policy", the most recent version of which was updated on 17th March 2022. The policy emphasises that the defendant seeks to pursue "Outcome Focused Enforcement". The four outcomes which are sought to be achieved by its enforcement activities are to stop illegal activity from occurring or continuing; to put right environmental harm or damage; to bring illegal activity under regulatory control and so ensure compliance with the law; and to punish an offender and deter future offending by that offender and others through the use of enforcement action. The policy goes on to emphasise the need to act proportionately and provides as follows:

- The policy identifies that enforcement action will be targeted in particular at those activities which cause the greatest risk of serious environmental damage and where risks are least well controlled. Enforcement action is also to be targeted to breaches which undermine the regulatory framework or where deliberate or organised crime is suspected. The policy includes enforcement and sanction penalty principles, which set out the aims of the enforcement activity in which the defendant engages. The policy provides as follows:

- Section 7 of the policy sets out the enforcement options that are available to the defendant in undertaking the exercise of its regulatory powers. As set out above the defendant identifies that an enforcement response should be designed to be proportionate and appropriate to the circumstances of the case. The first response will usually be to give advice or guidance or issue a warning to bring an offender into compliance where possible. Other more serious options include a range of civil sanctions which are available for use for many offences for which the defendant has the responsibility of enforcement. The policy sets out that the defendant "will normally consider all other options before considering criminal proceedings". Generally, the policy notes that prosecution is a last resort.

- The policy identifies a number of public interest factors which are set out to guide the question of the type of enforcement action which should be taken in respect of any particular breach. Those public interest factors start with the question of intent: the policy identifies that the defendant is more likely to prosecute when an offence has been committed deliberately, recklessly, or as a consequence of serious negligence. A further factor is foreseeability: if the circumstances leading to an offence could reasonably have been foreseen and no action was taken to avoid or prevent what occurred that will guide the nature of the enforcement sanction.

- Additional factors to be taken into account are the environmental effect of the breach; the nature of the offence in the sense of the extent to which it impacts upon the ability of the defendant to effectively regulate; the question of whether or not the breach was motivated by financial gain; and the deterrent effect of the choice of sanction. The public interest issues also include the previous history of the offender and, separately, their attitude to the offence and the defendant's investigation. Finally, the personal circumstances of the offender will also be taken into account, including factors such as any ill health and their ability to pay any financial sanction. Thus, it is submitted by the defendant, the policy provides a comprehensive spectrum of enforcement techniques together with a range of criteria to guide the defendant in exercising its regulatory powers.

- The defendant's approach to the enforcement of the 2018 Regulations is set out in a detailed witness statement from Mr William Crookshank who is an Agricultural Manager at the Environment Agency and whose role covers a broad range of issues in respect of the regulation of agriculture in England. In his witness statement Mr Crookshank explains that in July 2021 the defendant published a Frequently Asked Questions document ("the FAQ's") which set out its position in respect of the Farming Rules for Water. Following this, when the Statutory Guidance from the interested party was published in March 2022, the FAQs were reviewed and reframed. The status of the FAQ's is internal guidance for the defendant, and in particular a section of the FAQ's was devoted to the enforcement of regulation 4(1)(a)(i) reflecting how the defendant intended to have regard to the Statutory Guidance.

- In July 2022 the FAQ's were made available to the defendant's officers along with a template letter and internal supplementary guidance in respect of these issues. Initially in July 2022 the FAQ's suggested that if a land manager was operating within the terms of the Statutory Guidance, but the defendant's enforcement officer believed there to be a breach of Regulation 4 of the 2018 Regulations as interpreted by the defendant the officer should record that breach on the defendants' systems but not inform the land manager of this view. In the circumstances the officer would provide guidance to bring the land manager's operations back into compliance with the defendant's view of the 2018 Regulations.

- This approach, perhaps reflecting the difference of view in relation to the interpretation of regulation 4(1)(a)(i) between the defendant and the interested party, followed correspondence between the interested party and the defendant in which the interested party explained that their position in respect of the Statutory Guidance was that the defendant should not normally take enforcement action where a farmer was acting in accordance with the Statutory Guidance.

- Following the receipt of pre-action correspondence from the claimant, on 7th February 2023 the defendant changed its approach, and revised the FAQ's and internal supplementary guidance in March 2023. The new approach was that if the defendant considered that a land manager was in breach of the 2018 Regulations as interpreted by the defendant, the land manager would be informed of this even if they were complying with the provisions of the Statutory Guidance. This enabled the taking of informal enforcement action against such breaches, albeit that the internal supplementary guidance provided that enforcement action would not normally proceed beyond advice and guidance where a land manager could demonstrate compliance with the Statutory Guidance. A timescale for improvements via an action plan and record would be agreed to bring an operation into compliance within a reasonable timescale.

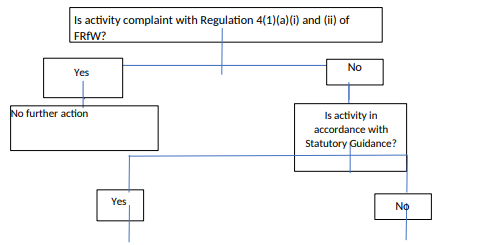

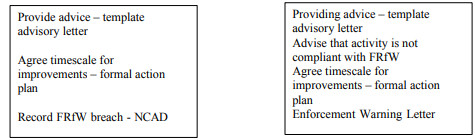

- This approach is set out in the form of a helpful flow chart diagram within the supplementary guidance as follows:

- The provision on the right-hand side of the diagram in respect of an activity which is not compliant with regulation 4(1)(a)(i), but in accordance with the Statutory Guidance, reflects the difference in interpretation between the defendant and the interested party as to the meaning and interpretation of regulation 4(1)(a)(i). It also, for instance, reflects the disagreement between the defendant and the interested party in respect of section 2.2 of the Statutory Guidance set out above (with emphasis added) in which the Statutory Guidance provides an exception in respect of applying organic manures to raise phosphorus levels above target levels where "it is not reasonably practicable to do so". The defendant observed in the course of submissions that such an exception is not anywhere provided for by the Regulations and its status could only be as a matter of discretion in relation to enforcement.

- These issues are further explored in the most recent version of the FAQ's published on 24th November 2023. The answers provided to FAQ's 7, 10 and 11 provide an illustration of the approach taken by the defendant, notwithstanding the difference of interpretation of regulation 4(1)(a)(i) between themselves and the interested party. Those questions and their answers, so far as relevant, provide as follows:

- In answer to FAQ 21, which asks about the enforcement regime, the answer makes clear that the defendant's approach will normally be to give advice and guidance in the first instance, but that the defendant will reserve the right to escalate enforcement and impose civil or criminal sanctions if the advice, guidance and warnings do not bring about the necessary change in behaviour to bring the operations of the land manager back under control.

- A further illustration of the defendant's approach in the light of the difference between its interpretation of regulation 4(1)(a)(i) and that of the interested party in the Statutory Guidance is provided in the response to FAQ 32. The answer explains how the defendant will operate its enforcement powers in the light of the difference between the contents of the Statutory Guidance and the defendant's interpretation of the 2018 Regulations. The text of this question and the answer to it is as follows:

- In Mr Crookshank's witness statement he describes the approach taken by the defendant's officers in respect of their day-to-day enforcement activities. After officers have undertaken an inspection, a record of their inspection findings is completed on a Farm Inspection Form and that record is added to the defendants' National Compliance Assessment Database ("NCAD"). The NCAD generates a post-visit letter. There is a template for the letter which provides a number of options and free text fields that can be completed by the officer to reflect the findings of the inspection. The findings following the inspection will include the improvements that are required by the land manager in order to achieve compliance with the Regulations and reduce any risk of pollution. The template letter, a copy of which is included within the bundle, has a specific section addressing the 2018 Regulations and incorporates options in relation to potential breaches of the Regulations and the steps necessary to bring the land management operation within compliance. In particular the template letter addresses the potential difference between a breach of the regulations applying the defendant's interpretation, and compliance with the Statutory Guidance in so far as it differs from that interpretation. The letter states in terms that the "legal requirements of the FRfW are not affected by the Statutory Guidance".

- Mr Crookshank explains in his evidence that the letter enables the defendant's officers to specify the steps that it is necessary to take, and the period of time over which they are to be taken, so as to ensure compliance with the 2018 Regulations. Mr Crookshank explains that where farmers do not comply within the timescale set out then the defendant will move to taking more formal enforcement action. However, Mr Crookshank records the defendant's experience that most satisfactory outcomes are secured through the provision of advice and guidance rather than the deploying of formal sanctions.

- A particular focus in the course of argument were the following paragraphs of the template letter relating to the defendant's approach to the enforcement of the 2018 regulations.

- It is, of course, important to bear in mind that the template letter is the starting point rather than the terminus of the defendant's enforcement activity, and it provides a structure or prompt to assist a bespoke response to the findings of the farm inspection. That this is the case is borne out by the evidence of specific enforcement activities provided by the defendant which is set out below.

- Turning to the evidence in respect of the practical activities of the defendant in enforcing the 2018 regulations, in his witness statement Mr Crookshank identifies that in 2021 significant additional funding was provided to the defendant for the purpose of enhancing its regulatory activity in respect of the agricultural sector. In addition, the interested party has provided funding to explore improvements to the ways in which the agricultural sector is regulated particularly through the delivery of additional farm inspections.

- Mr Crookshank's evidence records that between 1st January 2020 and 30th October 2023 the defendant had visited 409 farms and carried out 515 inspections within the Wye catchment. Of these 45% of the inspections were non-compliant with one or more of the 2018 Regulations, and 31% non-compliant with regulation 4(1)(a)(i). In his witness statement he provides the following description of the approach taken by the defendant in these circumstances:

- The table 5 referred to in this passage of Mr Crookshank's witness statement sets out at a national level the formal enforcement action taken beyond the provision of advice and guidance both before and after the publication of the Statutory Guidance.

- The contentions of the claimant are founded more specifically on identified examples of the defendant's approach to enforcement. It is unnecessary to set out all of the instances referred to for the purposes of this judgment, but it suffices to identify the principal examples which were relied upon. The first example is a letter in relation to a farm inspection which took place on 26th October and 1st December 2022. The inspection report relates to a number of different regulatory regimes but in particular the 2018 Regulations. Having set out the requirements of regulations 4 and 5 of the 2018 Regulations the document notes as follows.

- you could not demonstrate how soil sampling and analysis records were taken into account when planning applications.

- you could not demonstrate how you have planned your applications. The Nutrient Management Planning was not drawn up in advance of cropping. SNS was not calculated.

- The document goes on to note in relation to fields of particular concern that in respect of one field the application of material to the field had led to 10 times the amount needed for phosphorus, and 2.5 times the amount needed for potassium as well as the requirements for nitrogen being exceeded in another area. The report noted that the nutrient management plan showed that the soil and crop need for nitrogen at the time of application would be exceeded but would not be exceeded on an annual cycle of identified crops. The nutrient management plan also showed that there was a risk of the soil phosphorus index being raised above target levels for the crop rotation and it was already above the target level. The nutrient management plan showed that there was a significant risk of losing nitrogen and phosphorus to the environment which would be unavailable to the crop. The inspection report identified steps which should be taken in the form of making greater use of the existing phosphorus in the soil by not adding more organic manure to the identified fields; spreading at lower application rates; and considering what materials were being imported on to the land and the risks of nitrogen and phosphorus pollution. In the section of the inspection report entitled "Enforcement Response" the box was ticked identifying that the defendant would now consider what enforcement action was appropriate and notify the land manager accordingly.

- Following the change of approach in the FAQ's and the supplementary guidance noted above, a further specific example relied upon relates to an inspection which occurred on 23rd March 2023 addressed in covering correspondence dated 18th April 2023. The letter advised the land manager in the following terms:

- The farm inspection report went on to identify a number of issues and actions specifically which, for present purposes, were as follows:

- Whilst the SoS Guidance is in place, on fields with soils at P index 4, application rates of digestate will be managed to ensure that the total phosphate (rather than available phosphate) does not exceed the amount of phosphate that will be removed by the crops in that rotation. Applications will only be made once every two to three years at a rate appropriate to the current growing crop. This will ensure that crop offtake across the rotation will be much higher than input which will allow the index to run down. More frequent soil sampling will be undertaken on these fields to assess how the cropping practices and nutrient planning are affecting soil phosphate levels. These tests show the variation with the soil index so will be helpful in showing whether levels within an index have reduced for example a high P4 to a low P4.

- some rented land is farmed three years out of four, with the fourth year being farmed by a potato grower. Information will be obtained from the potato grower about what manures and fertilisers have been applied so that this can be factored into the nutrient planning on these fields. Sharing data between the two parties will ensure that both have the information needed to remain compliant with the Farming Rules for Water requirement to ensure that nutrient applications are matched to the needs of the crop and soil. Phosphate applied at all stages in the rotation needs to be considered to ensure compliance."

- What has been set out above are selected points from within a significant number of issues and actions which were identified within the inspection report. The report notes that all of the actions had been agreed and were to be implemented immediately. In the section of the inspection report entitled "Enforcement Response" the following box has been ticked:

- A further letter dated 24th August 2022 is relied upon by the claimants. This letter followed a farm inspection on 2nd August 2022 and was written to provide advice to enable the farm manager to improve or ensure compliance with regulations including the 2018 Regulations. The letter advises of the need to demonstrate how soil sampling and analysis records had informed applications, and of a need to demonstrate how applications had been planned. In particular, a number of steps are advised such as making greater use of the existing phosphorus in the soil by not adding manure to the fields or using alternative fields where possible. The steps are advised so that "you can more closely match to crop and soil need and reduce the risk of pollution to the water environment".

- In addition to this material, within the evidence are examples of warning letters following the defendant being satisfied that offences under the 2018 Regulations have been committed, but containing the conclusion that the defendant does not propose to take any further action in relation to those offences. All of this material is relied upon by the claimant in the context of submissions recorded below to the effect that the defendant is not lawfully enforcing the 2018 Regulations. By contrast the defendant submits that these are illustrations of the defendant properly applying a lawful policy in relation to the enforcement of the 2018 Regulations.

- The third theme of the cases in relation to the defendant's enforcement activities relates to the impact on the Wye as an SAC. The claimant draws attention to the agreed and documented deterioration in the favourable conservation status of the Wye SAC, and in particular the impact of phosphate pollution from diffuse sources upon water quality leading to that deterioration. Indeed, it is noted in the documentation that the historic build-up of legacy phosphate in the soils in the Wye catchment may take more than 10 years to address.

- Against this background the claimant notes that, akin to the case of Harris, the defendant is the sole regulator with responsibility for the 2018 Regulations and their enforcement, and that the continued deterioration in the water quality of the Wye caused by diffuse pollution demonstrates the inadequacy and failure of the enforcement activity taken by the defendant. It is said that these inadequacies demonstrate that the defendant is not having regard, as required by the relevant legislation, to the interests of the Wye SAC.

- In response to these submissions the defendant, through the evidence of Mr Crookshank, acknowledges that the impact of phosphorus, and in particular legacy phosphorus, is a significant issue which is recognised and being addressed. His evidence is that whilst it cannot be resolved overnight, it is an issue which has to be addressed through the cooperative and coordinated activity of a number of different regulatory organisations acting with the objective of avoiding the deterioration of the SAC in accordance with their duties under the Habitats Regulations.

- In particular, in 2014 the defendant and Natural England instigated the development of a Nutrient Management Plan ("NMP") in order to reduce phosphate concentrations in the Wye and comply with the Habitats Regulations. The NMP is overseen by a Nutrient Management Board attended by the defendant, Natural England, Natural Resources Wales, local authorities, Welsh Water and other non-governmental organisations. The terms of reference for the Board identified that its purpose is to identify and deliver actions to achieve the phosphorus conservation target of the Wye SAC through the provisions of the NMP.

- The NMP identifies sources of nutrients entering the river and the steps that can be taken to manage them, as well as including water quality data and identified actions. A River Wye Statutory Officers Group has been established to assist in ensuring that participants collectively use their statutory powers and resources to achieve the requirements of the relevant legislation in particular the Habitats Regulations. This Group meets monthly to ensure effective coordination of the responsible statutory authorities operating within the catchment to restore the conservation status of the Wye. This work is supported by a Technical Advisory Group to provide technical expertise and advice in supporting development and delivery of actions necessary to implement the NMP.

- In his evidence Mr Crookshank explains that the defendant is working on a broad range of initiatives, including targeted farm inspections and increased inspection of water sewage treatment works with the specific objective of preventing deterioration in the Wye's habitat. These activities are focused upon improving long-term water quality and addressing issues from diffuse agricultural pollution. A particularly innovative project which Mr Crookshank explains in his evidence is Project TARA. This project examined satellite and high-resolution aerial photographs to identify fields that were being left bare over the winter exacerbating the risk of run-off and soil erosion leading to pollution. The farmers concerned were asked if they had an agronomic justification for leaving the land bare and provided with advice and guidance in respect of ensuring that they were in compliance with the 2018 Regulations, and in particular Regulation 10 which requires reasonable precautions to be taken in relation to soil erosion. Mr Crookshank explains that the defendant has learned from the experience of this test exercise and is programming a further exercise in remote sensing inspections in the Wye catchment.

- In addition to this, the defendant observes that the Statutory Guidance applies nationally, whereas the interests of the Wye SAC are specifically acknowledged in the defendant's internal documentation in respect of its enforcement activities. For instance, at paragraph 8.1.3 of the defendant's Enforcement and Sanctions policy, where a specific decision is taken in relation to enforcement the policy requires that the public interest factors to be taken into account will include the environmental effect of any non-compliance, and that the more serious the environmental effect the more potent the enforcement response will be. Thus, the defendant contends that the enforcement policy specifically addresses the importance of the environmental impact on an SAC site such as the Wye. Under the defendant's Incidents Classification Scheme, which categorises impact on nature conservation sites, and which informs the enforcement policy, category 1 and category 2 incidents are defined so as to ensure that any damage to a nationally protected habitat of this kind is at least a category 2 incident. Under paragraph 8.1.3 of the enforcement policy this will lead the defendant to normally consider "a prosecution, formal caution or a VMP [a variable monetary penalty]".

- Returning to the NMP, the defendant notes that this document observes that the issues in relation to phosphate arise from discharges from a number of potential sources. In addition to point sources such as industrial or wastewater treatment works there are also other contributors in the form of urban drainage and leaking sewers, combined sewer overflows and septic tanks. For this reason, the defendant contends that there needs to be a joined-up approach engaging in a range of regulators with responsibility for regulating these potential sources. The NMP itself notes that there will need to be a "mixture of policy instruments" to ensure that appropriate initiatives are taken and effectively implemented. Within the NMP a wide range of regulatory regimes are identified all of which could contribute to tackling the issue of phosphate pollution of the Wye, including the potential for the interested party to introduce a Water Protection Zone. This, it is said, is what led to the NMP adopting a multi-agency approach to tackling the issue of improving the nature conservation status of the Wye. The defendant notes the support for the multi-agency approach in the documentation, including in particular the support of Natural England.

- Whilst it is not directly engaged by any of the claimant's grounds, there is an issue between the parties as to the correct interpretation of regulation 4(1)(a)(i) of the 2018 Regulations which all parties accept the court ought to resolve as part and parcel of its decision in this case. In particular, the dispute relates to the question of whether or not, as contended by the claimant and the defendant, the correct interpretation of regulation 4(1)(a)(i) of the 2018 regulations is that the application of organic manure or manufactured fertiliser should be planned so as not to exceed the needs of the soil and crop on the land at the time of the application, or whether it is appropriate to consider need over a longer period, as contended for by the interested party and the intervener, this interpretation is inappropriate. Indeed, the intervener contends that regulation 4(1)(a)(i) should be interpreted so as to entitle consideration of the soil and crop need over a lengthier future period, such as for instance an annual crop cycle or crop rotation.

- In support of their construction of regulation 4 both the claimant and the defendant draw attention to the purpose for which the regulation was enacted. Regulation 4, and indeed the 2018 Regulations generally, were enacted for the purpose of preventing the pollution of waters from diffuse agricultural sources. The purpose behind their preparation is emphasised in the Explanatory Note prepared to support the regulations, and the background to their drafting which is set out above.

- The claimant and the defendant submit that regulation 4(1)(a)(i) creates a duty to plan for the application of organic manure or manufactured fertiliser, and to plan for each application. This can be identified from the fact that the application appears three times in the course of regulation 4(1). In effect that word bookends the requirement of planning, and emphasises therefore that the plan must be made at the time of the application, and must be devised and based on needs of the soil and crop at the time of the application and not at some notional time in the future for some anticipated future crop. A part of the purpose of Regulation 4(1)(a)(i) is to avoid the risk of the application of organic manure or manufactured fertiliser that is surplus to the needs of the soil and crop and which may not be absorbed but become the subject of leaching or run-off. Furthermore, this interpretation is reinforced by the provisions of regulation 5, which are also directed to an understanding of soil sampling and analysis at the time of the application.

- A further factual reinforcement of this interpretation is, it is submitted, that a soil and crop need in relation to nitrogen and phosphorus are different in that they perform differently over the course of time in the soil. Thus, it is submitted by the claimant and the defendant, it is no accident that regulation 4(1) is in fact a single sentence, and that it needs to be interpreted and applied on the basis that the planning of each application must be designed so as to not exceed the needs of the soil and crop on the land at the time that the application is to take place. Furthermore, it is no accident and indeed it is intentional, that regulation 4(1)(a)(i) speaks of the needs of the soil and crop on the land at the time of the application. This further reinforces the interpretation that the needs of the soil and crop are to be assessed at the time when the application is to take place. It is all of a piece with the wording of paragraph 4(1)(b), which requires account to be taken of weather conditions and forecasts for the land "at the time of application".

- The interested party resists this interpretation of the legislation for the following reasons. Firstly, it is submitted by the interested party that the creation of a duty to plan the application imports a consideration of the future needs of the soil and crop on the land, permitting planning to occur for crop rotation or over a crop cycle where appropriate. Whether or not it may be appropriate is then a matter of judgment for the land manager or the defendant in applying and operating the legislation. The requirement under regulation 4(1)(b) in relation to whether conditions and forecasts is separate and divorced from the obligation to plan in regulation 4(1)(a), and it is significant that there are no words limiting the needs of the soil and crop to those needs immediately arising. The use of the word "on" within regulation 4(1)(a)(i) is a preposition, rather than as argued by the defendant a word with a temporal implication. Thus, it is submitted that correctly interpreted there is nothing to preclude planning for longer term needs of the soil and crop within the terms of the legislation.

- By way of background to this interpretation the interested party points out that the regulations were intended to reflect existing good practice as identified within the consultation material about them. The interested party draws attention to its publication "Protecting our Water, Soil and Air: A Code of Good Agricultural Practice for farmers, growers and land managers". Within that document the following is observed in relation to organic manures:

- the soil is waterlogged, flooded, frozen hard or snow-covered; or

- there is a significant risk of nitrogen getting into surface water via run-off, taking into account in particular the slope of the land, weather conditions, ground cover, proximity to surface waters, soil conditions and the presence of land drains.

- 10 metres of surface waters, including field ditches; or

- 50 metres of a spring, well or borehole.

- In the above quotation the interested party draws attention to paragraph 74 indicating that organic manures not containing much readily available nitrogen can be spread at any time. Further advice is contained within this Code of Good Practice in relation to phosphorus in the following terms:

- In a similar way, the interested party draws attention to a publication of the Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board entitled the Nutrient Management Guide which contains the following in respect of firstly nitrogen and secondly, phosphorus and their management in the application of nutrients:

- Readily available nitrogen (i.e. ammonium-N as measured by N meters, nitrate-N and uric acid-N) is the nitrogen that is potentially available for rapid crop uptake

- Organic-N is the nitrogen contained in organic forms, which are broken down slowly to become potentially available for crop uptake over a period of months to years

- Ammonium-N can be volatilised to the atmosphere as ammonia gas

- Following the conversion of ammonium-N to nitrate-N, further losses may occur through nitrate leaching and denitrification of nitrate to nitrous oxide and nitrogen gas under warm and wet soil conditions

- The intervener submits that the claimant and the defendant's interpretation is unsustainable on the basis that the question of "the needs of the soil and crop on that land" are not qualified by any language suggesting that it is the needs of the time of the application which are definitive. Parliament specifically did not include "current needs" in the drafting of this regulation, and therefore it is submitted that the claimant and the defendant promote an unjustifiable gloss on the language of the regulation. The intervener supports the submission of the interested party that the requirement to plan includes within it an implication of projecting or looking forward to the needs of the soil and crop arising in the future.

- Whilst the intervener accepts that the words "at the time of the application" arise within regulation 4(1)(b), they draw attention to cases such as Shepherd v Information Commissioner [2019] 4 WLR 50; [2019] EWCA Crim 2 in which the court observed that where the legislature chooses one form of words on three occasions, and a different formulation on another two, there is a strong indication that it is the intention of Parliament that two different legal results should be the outcome of that differing use of words. Thus, the language in regulation 4(1)(b) reinforces that regulation 4(1)(a)(i) should not be interpreted as including the language "at the time of the application". Furthermore, it is submitted on the evidence that the requirement to ensure that an application is planned so that it does not "give rise to a significant risk of agricultural diffuse pollution" favours an autumn application of organic manure or manufactured fertiliser over that of one in the spring.

- In addition to these submissions the intervener draws attention to the case of R(PACCAR Inc & others) v Competition Appeal Tribunal and others [2023] 1 WLR 2594; [2023] UKSC 28, and the assistance which it provides in respect of the principle of statutory interpretation that the court should seek to avoid a construction of legislation which produces an absurd result. This was explained by Lord Sales, in a judgment with which the majority of the Supreme Court agreed, in the following terms at paragraph 43 of his judgment:

- The intervener submits, based upon the evidence which is set out above as to the implications of the claimant and the defendant's interpretation of the legislation, that it is impractical. The intervener notes that the claimant's own evidence on this topic supports an application of nutrients prior to them being required by a crop, and relies upon the evidence of Mr Williams to demonstrate that the claimant and the defendant's interpretation requiring an assessment of needs solely at the time of the application without account being given to crop demands which might arise over the course of a crop rotation or crop cycle being impractical, and having the potential to give rise to a greater risk of diffuse pollution than the interpretation given by the intervener.

- Finally, the intervener draws attention to the fact that breaches of regulation 4 have a criminal sanction, and therefore when considering the correct interpretation of that regulation it is critical to bear in mind the serious consequences in the form of criminal enforcement, and the importance of legal certainty in providing any interpretation of the Regulation, which the intervener submits, supports its approach to interpretation of regulation 4(1)(a)(i).

- Having reflected on the competing submissions on the topic of the interpretation of Regulation 4(1)(a)(i) I have concluded that I am satisfied that the correct interpretation is that set out in the submissions of the claimant and the defendant. I have reached this conclusion for the following reasons.

- Firstly, in my view the claimant and the defendant are right to emphasise the importance of the purpose of these regulations, widely advertised in the consultation materials and also explained in the Explanatory Note, to reduce diffuse agricultural pollution giving rise to significant risks of deterioration in water quality by avoiding the risks of application of nutrients surplus to requirements of the soil and crop leaching or running off and giving rise to diffuse pollution. In principle, the furtherance of that purpose is more likely to be achieved by planning for the needs of the soil and crop on the land at the time when the application is to take place. It is more likely to be furthered as an objective on the basis of known soil and crop needs at the time of the application, rather than forecast or potential crop needs that might arise from some future notional but as yet unimplemented crop cycle or rotation. Interpretating Regulation 4(1)(a)(i) of the 2018 Regulations in this way is in my view consistent with the clear purpose of enacting this legislation, to ensure that applications of organic manure or manufactured fertiliser are tailored to the known and established needs of the existing soil and crops so as to avoid the risks of overprovision and subsequent leaching or run-off of unabsorbed nutrients into water courses giving rise to environmental damage. Thus, it is clear in my view that the purpose of the regulation supports the claimant and the defendant's interpretation. The contentions in relation to farming operations and practicality are dealt with in detail below, but it is important to note that this evidence is framed in the context of current practices, as opposed to practices being shaped by and conforming to the proper application of Regulation 4(1)(a)(i) of the 2018 Regulations and its clear purpose.

- I am reinforced in that conclusion by an examination of the language of regulation 4 and its surrounding regulatory context. In my view the defendant is correct in placing reliance upon the use of the word "on" within regulation 4(1)(a)(i) as being far more consistent with an interpretation of regulation 4 which requires the need of the soil and crop to be planned and determined at the time of the application. I am unable to accept the interested party's submission that this word is simply used as a preposition in this context. Its use brings with it the clear indication that the planning of the application called for by regulation 4 is to be based upon the needs of the soil and crop on the land at the time when the planning is being undertaken.

- It is also of significance in my view that regulation 4(1) is written as a single sentence incorporating both regulation 4(1)(a) and (b). Thus the natural reading of that sentence as a whole, bearing in mind in particular that (a) is linked to (b) by the use of the word "and", is that the planning which is to be performed in relation to soil and crop needs, the avoidance of significant risk of agricultural diffuse pollution and account being taken of weather conditions and forecasts are all to be undertaken "at the time of the application". In short, the defendant's observation that the word "application" provides the bookends for regulation 4(1) legitimately reinforces the claimant and the defendant's interpretation.

- In my view cases such as the case of Shepherd are of little assistance in relation to the question of construction which arises in this case. As noted above, the case of Shepherd addressed different formulations of words in different sections of the same act. The point of the construction which arises in this case relates, in effect, to the single sentence which comprises the regulation which is under consideration. Reading that sentence as a whole, given the language and the context, reinforces the conclusion that the claimant and the defendant are correct in their interpretation of regulation 4.

- Whilst I have noted the extracts from the Code of Good Practice relied upon by the interested party in relation to nitrogen, that good practice emphasises the need for applications to be made at a suitable time for maximum crop growth of the specific crop concerned. This does not in my mind undermine the claimant and the defendant's interpretation or lead to a different conclusion. Whilst the material in relation to phosphate and potash refers to managing the application of organic material to ensure that it is used through the crop rotation, that again does not in my view provide a coherent basis to go behind the claimant and the defendant's interpretation when regard is properly had to the purpose of the regulations and the way in which its requirements for planning applications have been articulated in the legislation. It is the language of Regulation 4(1)(a)(i) which is central to the task of interpretation, and the terms of prior guidance (which is far from unequivocal on these issues) is insufficient to undermine the clear conclusions I have reached based on the language of the 2018 Regulations and their purpose.

- It is important to note that, additionally, regulation 5 of the 2018 Regulations is clearly framed in respect of the results of soil sampling and analysis being current at the time of the application. This is a further feature of the context of regulation 4 which supports the interpretation advanced by the claimant and defendant.