Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

England and Wales High Court (Administrative Court) Decisions

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> England and Wales High Court (Administrative Court) Decisions >> FA Gill Ltd & Ors, R (On the Application Of) v Food Standards Agency [2022] EWHC 1709 (Admin) (07 July 2022)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Admin/2022/1709.html

Cite as: [2022] EWHC 1709 (Admin)

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

Neutral Citation Number: [2022] EWHC 1709 (Admin)

Case No: CO/3532/2021

IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE

QUEEN’S BENCH DIVISION

ADMINISTRATIVE COURT

Royal Courts of Justice,

Strand,

London, WC2A 2LL

Date: 7 July 2022

Before :

MR JUSTICE MOSTYN

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Between :

|

|

THE QUEEN (on the application of) (1) FA GILL LIMITED (2) G&G B HEWITT LIMITED (3) C S MORPHET & SON LIMITED (4) T SOANES & SON (POULTRY) LIMITED (5) SPENBOROUGH ABATTOIR LIMITED (6) A WRIGHT & SON (A Firm)

|

Claimants |

|

|

- and –

|

|

|

|

FOOD STANDARDS AGENCY |

Defendant |

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Hugh Mercer QC and Naomi Hart (instructed by Roythornes Solicitors) for the applicant

Brendan McGurk (instructed by Flint Bishop Solicitors) for the respondent

Hearing dates: 21-22 June 2022

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

APPROVED JUDGMENT

Mr Justice Mostyn:

1. When a farmer takes his lambs to the abattoir a government vet will check the animals for disease on arrival, and will check the carcasses post-mortem to the same end. Under retained EU law the government can pass on the vet’s costs to the abattoir but is obliged to provide not merely to the abattoir, but to the public at large, clear details of how the costs are calculated. The government does so by posting information on the Food Standard Agency’s website in the page “Charges for controls in meat premises”[1]. The issue in this case is whether the information thus provided is sufficiently clear.

The parties

2. The claimants are six food business operators (“FBOs”) working within the meat sector. Each is a member of the Association of Independent Meat Suppliers (“AIMS”), a trade association which represents its members in all stages of meat processing in the red meat, poultry, and game sectors.

3. The defendant, the Food Standards Agency (“FSA”), is a non-ministerial government department established by section 1 of the Food Standards Act 1999.

4. The claimants challenge the decision of the FSA to issue invoices against each of them in July 2021 for the recovery of certain costs pursuant to EU Regulation 2017/625 on official controls and other official activities performed to ensure the application of food and feed law, rules on animal health and welfare, plant health and plant protection products (“the EU Regulation”).

The EU Regulation

5. The EU Regulation, incorporated into domestic law[2] and subsequently amended,[3] concerns “(a) the performance of official controls and other official activities by the competent authorities of the Member States; and (b) the financing of official controls” (Article 1(1)). The “official controls”, in turn, concern the rules, whether established domestically or at the level of the EU, in the areas of:

“(a) food and food safety, integrity and wholesomeness at any stage of production, processing and distribution of food, including rules aimed at ensuring fair practices in trade and protection consumer interests and information, and the manufacture and use of materials and articles intended to come into contact with food;

(b) deliberate release into the environment of Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs) for the purpose of food and feed production;

(c) feed and feed safety at any stage of production, processing and distribution of feed and the use of feed, including rules aimed at ensuring fair practices in trade and protecting consumer health, interests and information;

(d) animal health requirements;

(e) prevention and minimisation of risks to human and animal health arising from animal by-products and derived products;

(f) welfare requirements for animals;

(g) protective measures against pests of plants;

(h) requirements for the placing on the market and use of plant protection products and the sustainable use of pesticides, with the exception of pesticides application equipment;

(i) organic production and labelling of organic products;

(j) use and labelling of protected designations of origin, protected geographical indications and traditional specialities guaranteed.” (Article 1(2))

6. As summarised by the FSA, official controls therefore

“…consist in the provision of a range of veterinary and meat hygiene controls designed to ensure animal welfare and food safety where animals the subject of Official Controls are to be slaughtered for human consumption”.

7. The claimants’ evidence more specifically identifies that

“…the official controls consist of ante-mortem inspection of animals prior to slaughter, post-mortem inspection of carcases and offal after slaughter and dressing, and verification of the FBOs’ controls on hygiene and animal health and welfare.”

8. The FSA is the “competent authority” within the meaning of Article 4 of the EU Regulation[4], and is therefore responsible for undertaking the “official controls”. In the discharge of its duties, the FSA can delegate certain official control tasks to delegated bodies or natural persons, so long as certain conditions set out in the EU Regulation are met. Delegable natural persons include an “official veterinarian”[5] (“OV”) as well as an “official auxiliary”[6] (“OA”[7]).

Costs of performing official controls

9. Article 79 of the EU Regulation, and the amended Meat (Official Controls Charges) (England) Regulations 2009, require the FSA to collect certain costs associated with performing official controls.

10. Article 81 of the EU Regulation exhaustively identifies those costs as follows:

“(a) the salaries of the staff, including support and administrative staff, involved in the performance of official controls, their social security, pension and insurance costs;

(b) the cost of facilities and equipment, including maintenance and insurance costs and other associated costs;

(c) the cost of consumables and tools;

(d) the cost of services charged to the competent authorities by delegated bodies for official controls delegated to these delegated bodies;

(e) the cost of training of the staff referred to in point (a), with the exclusion of the training necessary to obtain the qualification necessary to be employed by the competent authorities;

(f) the cost of travel of the staff referred to in point (a), and associated subsistence costs;

(g) the cost of sampling and of laboratory analysis, testing and diagnosis charged by official laboratories for these tasks.”

11. Recital 66 of the EU Regulation further provides that:

“Fees or charges should cover, but not exceed, the costs, including overhead costs, incurred by the competent authorities to perform official controls. Overhead costs could include the costs of the support and organisation necessary for planning and carrying out the official controls. Such costs should be calculated on the basis of each individual official control or on the basis of all official controls performed over a given period of time. Where fees or charges are applied on the basis of the actual cost of individual official controls, operators with a good record of compliance should bear lower overall charges than non-compliant ones, as they should be subject to less frequent official controls. In order to promote compliance with Union legislation by all operators irrespective of the method (based on actual costs or on a flat rate) that each Member State has chosen for the calculation of the fees or charges, when fees or charges are calculated on the basis of overall costs incurred by the competent authorities over a given period of time, and imposed on all operators irrespective of whether they are subject to an official control during the reference period, those fees or charges should be calculated so as to reward operators with a consistent good record of compliance with Union agri-food chain legislation.”

12. Pursuant to the EU Regulation, costs can be calculated in one of two ways. The first option is in accordance with Article 82(1), the FSA might charge using: i) a flat rate on the basis of the overall costs of official controls borne by the competent authorities over a given period of time; and/or ii) the calculation of the actual costs of each individual official control, applied to the operators subject to such official control. The alternative option is in accordance with the fee schedule in Annex IV, which in essence provides for a price per animal, with different prices for different species. The FSA has opted for the former, and charges on a flat rate basis with rates calculated for an annual charging period in advance and on a budgeted basis. The annual charging period is the financial year. The FSA, in its summary grounds of resistance, explained its methodology for calculating charges as follows:

“It does this by looking at the total recoverable costs it incurred in the previous annual charging period, considers the extent to which these costs need to be revised upwards or downwards for the forthcoming charging period, and then estimates the total number of hours of Official Controls that will likely be required in order to provide the estimated level of Official Controls in the forthcoming charging period. The defendant then divides the total budgeted recoverable cost by the total budgeted number of required hours to produce an hourly rate for OVs and OAs. It then charges all FBOs those hourly rates dependent on how many hours of OV and OA time are in fact required by each FBO.”

13. The headline charge generated by the application of the hourly rate is mitigated by a discount. In April 2016 the FSA moved to what it describes as:

“a banded approach whereby the fewer the number of hours of Official Controls required by a particular FBO, the greater the discount that the FBO would receive from the FSA”.

14. The FSA states that “[t]he approach had the twin benefit of: (i) affording a greater discount to smaller plants and (ii) incentivising FBOs to be more efficient since the fewer hours of OV and OA time required, the greater the potential discount that would be available to that FBO”.

15. Needless to say, the hourly rates tend to go up every year. The new hourly rates will have been the subject of discussion with the meat industry. The new hourly rates are published by the FSA before the start of the financial year in its Charging Guide. This is posted on the website.

The duty of transparency

16. In levying such charges, the FSA is subject to a duty of transparency.

17. Recital 39 of the EU Regulation states:

“The competent authorities act in the interest of operators and of the general public ensuring that the high standards of protection established by Union agri-food chain legislation are consistently preserved and protected through appropriate enforcement action, and that compliance with such legislation is verified across the entire agri-food chain through official controls. The competent authorities, as well as delegated bodies and natural persons to which certain tasks have been delegated, should therefore be accountable to the operators and to the general public for the efficiency and effectiveness of the official controls they perform. They should provide access to information concerning the organisation and performance of official controls and other official activities, and regularly publish information concerning official controls and the results obtained.” (Emphasis added).

18. Recital 68 states:

“The financing of official controls through fees or charges collected from operators should be fully transparent, so as to enable citizens and businesses to understand the method and data used to establish fees or charges.” (Emphasis added).

19. Article 85 of the EU Regulation promulgates the duty. It states:

“1. Competent authorities shall ensure a high level of transparency on:

(a) the fees or charges provided for in point (a) of Article 79(1), Article 79(2), and Article 80, namely on:

(i) the method and data used to establish these fees or charges;

(ii) the amount of the fees or charges, applied to each category of operators and for each category of official controls or other official activities;

(iii) the breakdown of the costs, as referred to in Article 81.

2 Each competent authority shall make available to the public the information referred to in paragraph 1 of this Article for each reference period and the costs to the competent authority for which a fee or charge is due in accordance with point (a) of Article 79(1), Article 79(2) and Article 80.

3 Competent authorities shall consult relevant stakeholders on the general methods used to calculate the fees or charges provided for in point (a) of Article 79(1), Article 79(2) and Article 80.”

(Emphasis added)

20. In my judgment this is lex specialis and it is not necessary for me to examine examples of the application of the requirement of transparency in other spheres. The examples cited to me are, save in one instance, all cases where the requirement is judge-made, reflecting the demands of procedural fairness. In one case, MP v BP (C-212/20), the Court of Justice addressed the interpretation of transparency obligations laid down in Article 5 of Directive 93/13 on the issue of unfair terms in consumer contracts. The factual context contemplated by that Directive is a far cry from the present case (although the Court’s findings are very similar to those made by me here). In contrast, the duty in this case is spelt out in the EU Regulation and it is my clear opinion that its requirements are to be found within its four corners.

21. The wording of Article 85, read against the backdrop of Recitals 39 and 68, tells me that:

i) the duty of transparency is “high”;

ii) it must have been formulated following consultation with FBOs;

iii) it must reflect the obligation of accountability of the FSA to the meat industry and the public at large;

iv) it is owed formally to the public alone, meaning that there is only one standard of transparency;

v) it specifically requires a high level of transparency as regards:

a) the total costs, broken down by reference to the categories in Article 81, that are sought to be charged to FBOs by way of fees,

b) the method and data used to calculate the hourly rates, and

c) the amount of the charges thus calculated.

22. If a non-tangible thing, such as a piece of information, is required to be transparent then the person considering the thing must be able to drill down to its foundations and thereby to understand how the thing has been constituted. Therefore, the ‘high level of transparency’ required by Article 85 means that sufficient information must be provided to enable a reasonably astute member of the public to understand, broadly (and I emphasise broadly) how the hourly rates have been calculated. This means that the source data must be clearly stated, and the steps in the calculation process clearly explained, using plain English.

The FSA’s contract with Eville & Jones GB Limited

23. The FSA entered into a contract with Eville & Jones GB Limited (“E&J”), following a tender competition in 2019, effective from 30 March 2020 to run until 26 March 2023. Pursuant to that contract, E&J receives payment for carrying out, among other things, official controls at the premises of FSA-approved meat and dairy establishments, including those of the claimants. E&J fulfils the contract via OVs and MHIs, whom it contracts with or employs directly. E&J supplies all OVs and about half of all MHIs providing official controls in England. The other MHIs deployed in England are employed in-house by the FSA.

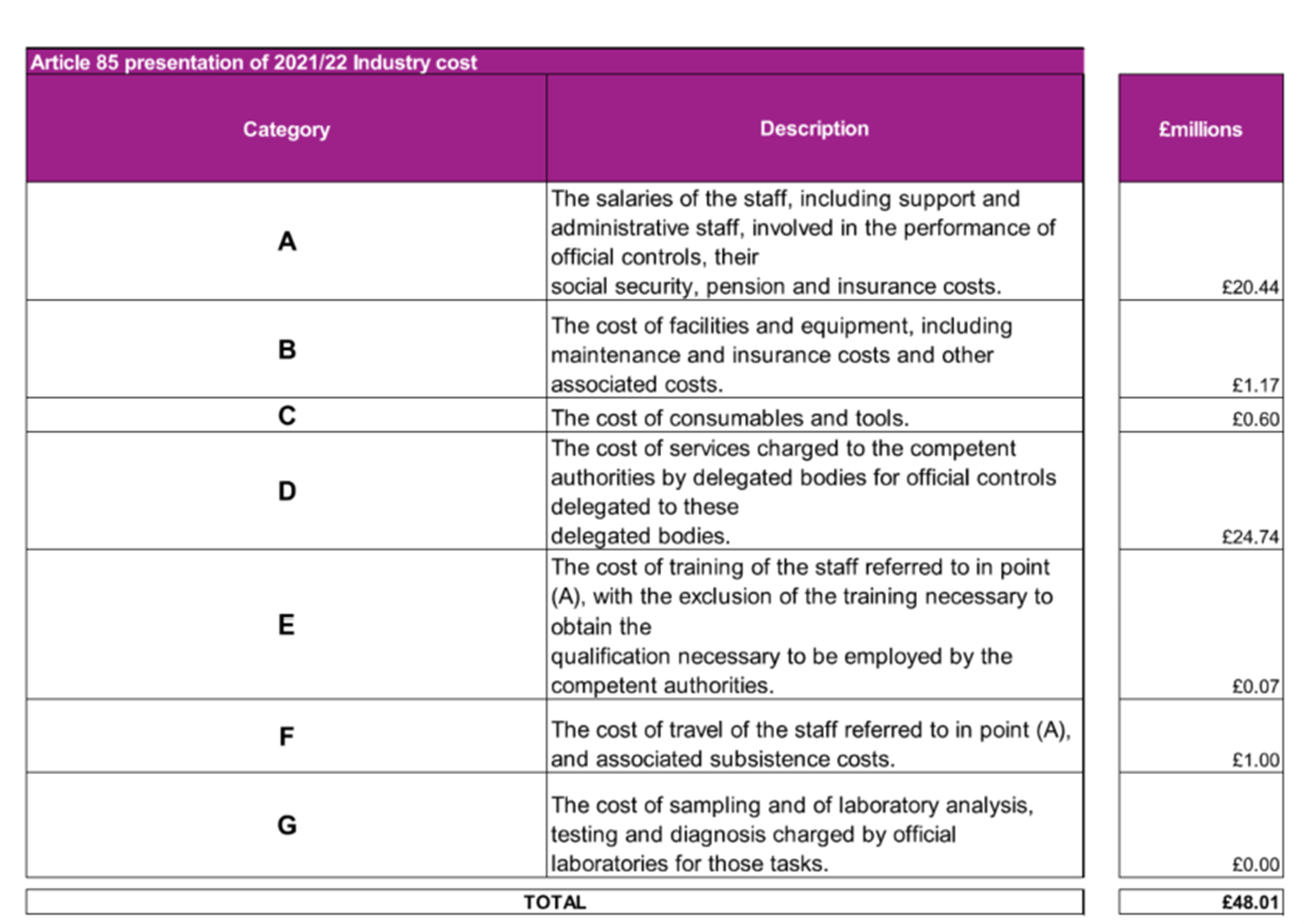

24. Previously, and as communicated to AIMS on various occasions in 2019, the FSA’s position was that it was entitled to collect from FBOs the contractual costs it paid to E&J on the footing that E&J was a “delegated body” pursuant to Article 81(d) of the EU Regulation. The FSA therefore published a document on its website entitled “Cost Data Slides for 2021/22”, of which slide 38 is entitled “Mapping to Article 85” (i.e. the transparency duty). The table on slide 38 identified total Article 81 costs of £48.01m, with costs of delegated bodies being £24.74m:

25. AIMS then raised a query whether E&J was in fact a delegated body, and if it was not whether its cost could validly be included as an Article 81 item. Correspondence with the FSA from June 2020 to 26 May 2021 explained initially that the question of whether E&J was a “delegated body” was under review. Later it was accepted in correspondence that E&J was not a delegated body. Unsurprisingly, the FSA did not agree that the absence of delegation prevented the inclusion of E&J costs in the calculation of the hourly fees and stated that “[t]he error only affected how the data was mapped to Article 81”. The FSA was therefore saying that while it would be necessary to adjust the Article 81 pigeon-holing this would not affect the overall quantum of the chargeable cost. In its summary grounds of resistance the FSA stated that it now considered it and E&J to be in a relationship of agency.

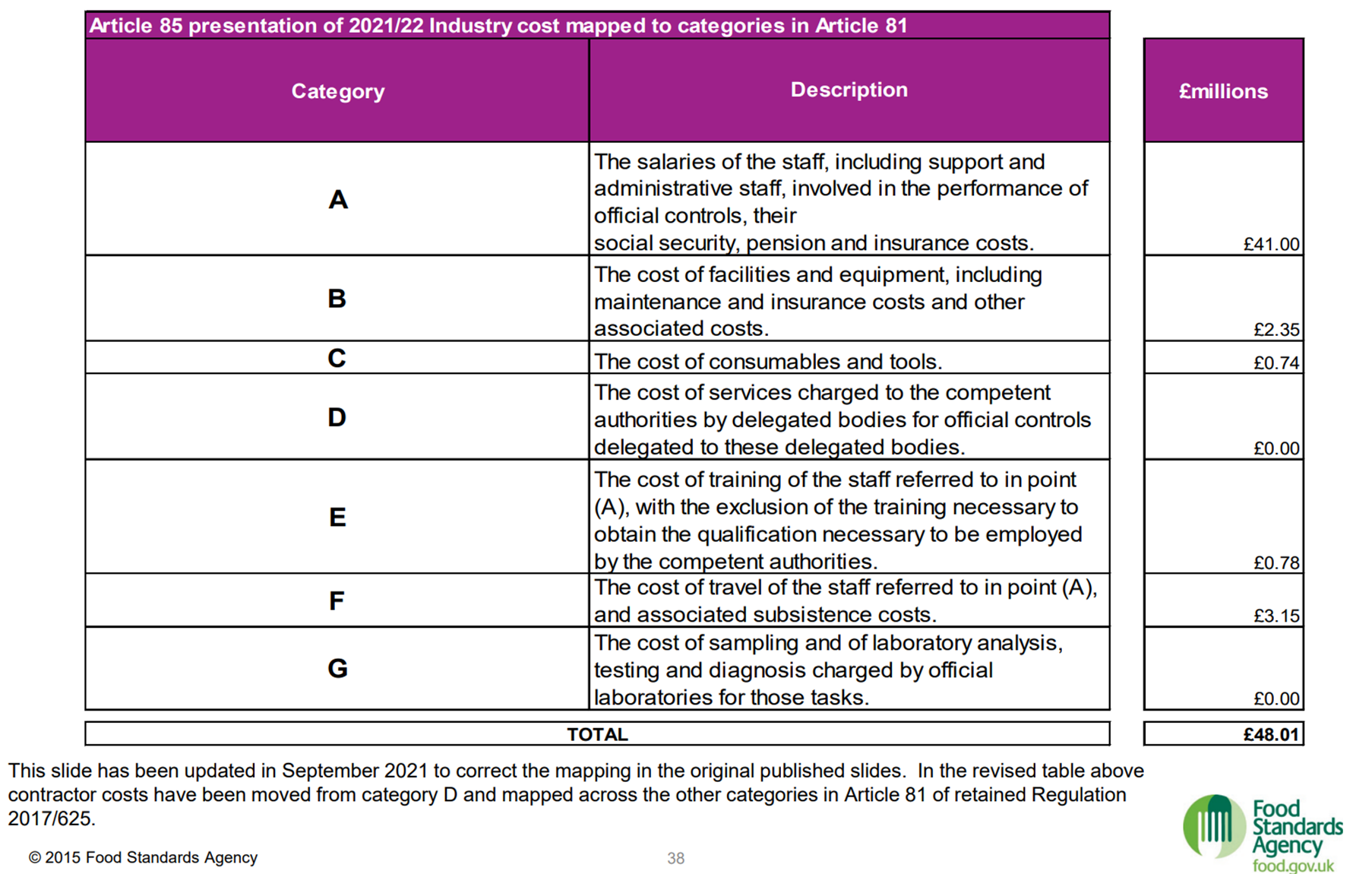

26. A revised costs mapping document was provided on 8 September 2021, accompanying the FSA’s PAP letter of response. It is on the FSA’s website[8]. It shows:

27. I draw attention to the explanation at the bottom of the slide.

28. The alteration of the figures in categories B, C, E, F and G was initially difficult to understand but it has been explained to me to my satisfaction by Mr McGurk. I will set out that explanation later in this judgment.

29. In its summary grounds of resistance, the FSA stated:

“…although the contract was awarded to E&J in a manner whereby E&J can recover, for example, an amount by way of profit, the FSA has not, in the invoices the subject of this claim, sought to pass on to industry any sum in respect of the profit cost it incurs as a result of providing Official Controls through a third party under a public contract”.

30. The case before me has proceeded on the basis that at no time in the future will the hourly fees be calculated on a basis that includes the agent’s profit.

The Decisions

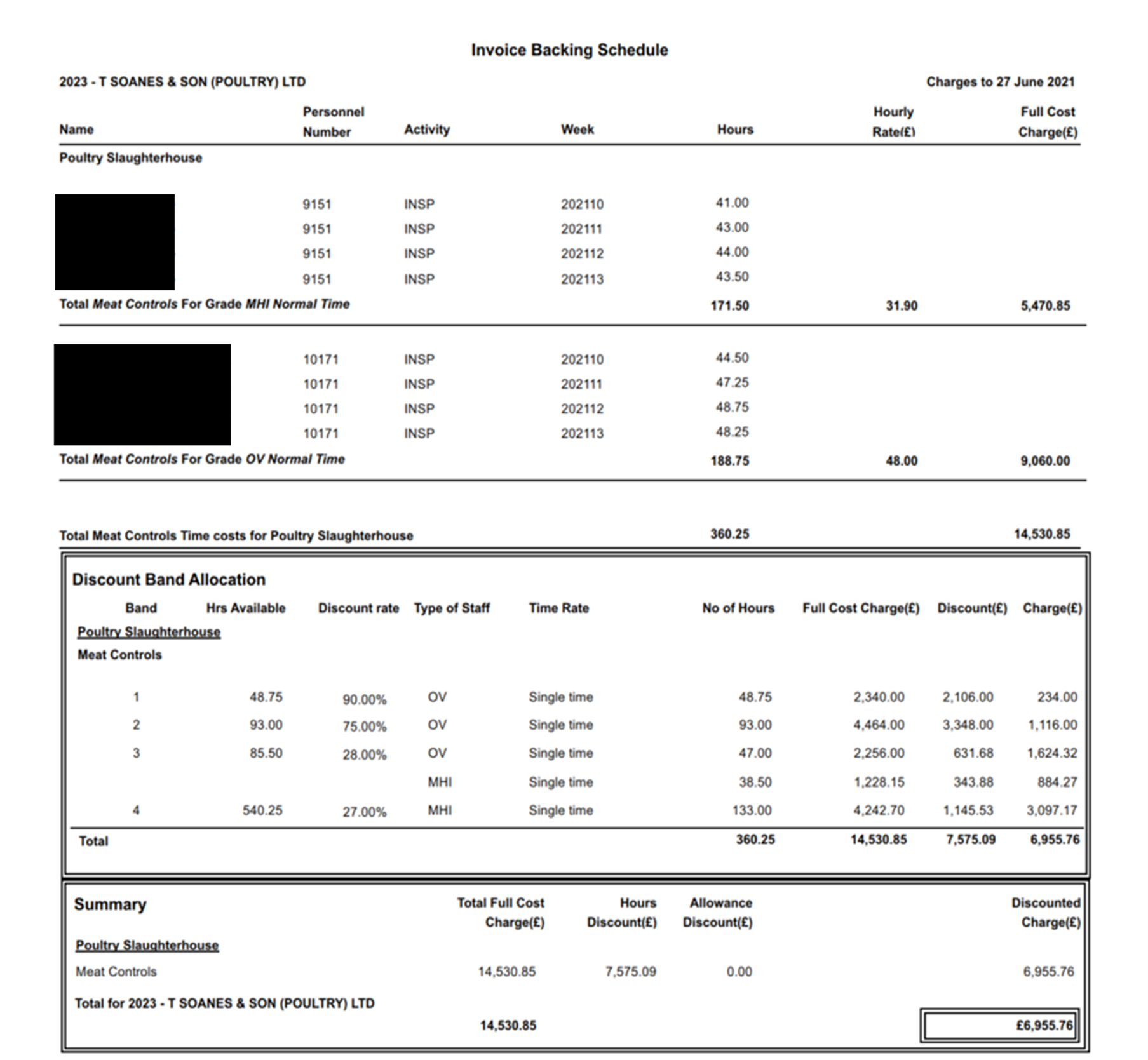

31. The FSA issued invoices dated 13 July 2021 (“the Invoices”) to each of the claimants. Each were for charges levied for the four weeks up to 27 June 2021[9]. The backing schedules of each invoice show that the charges were for either official controls or for unworked hours. The invoices were calculated using the data for the financial year 2021/22.

32. In order to illustrate the detail of the invoice I reproduce the backing schedule sent to the fourth claimant in the sum of £6,955.76 for slaughterhouse charges:

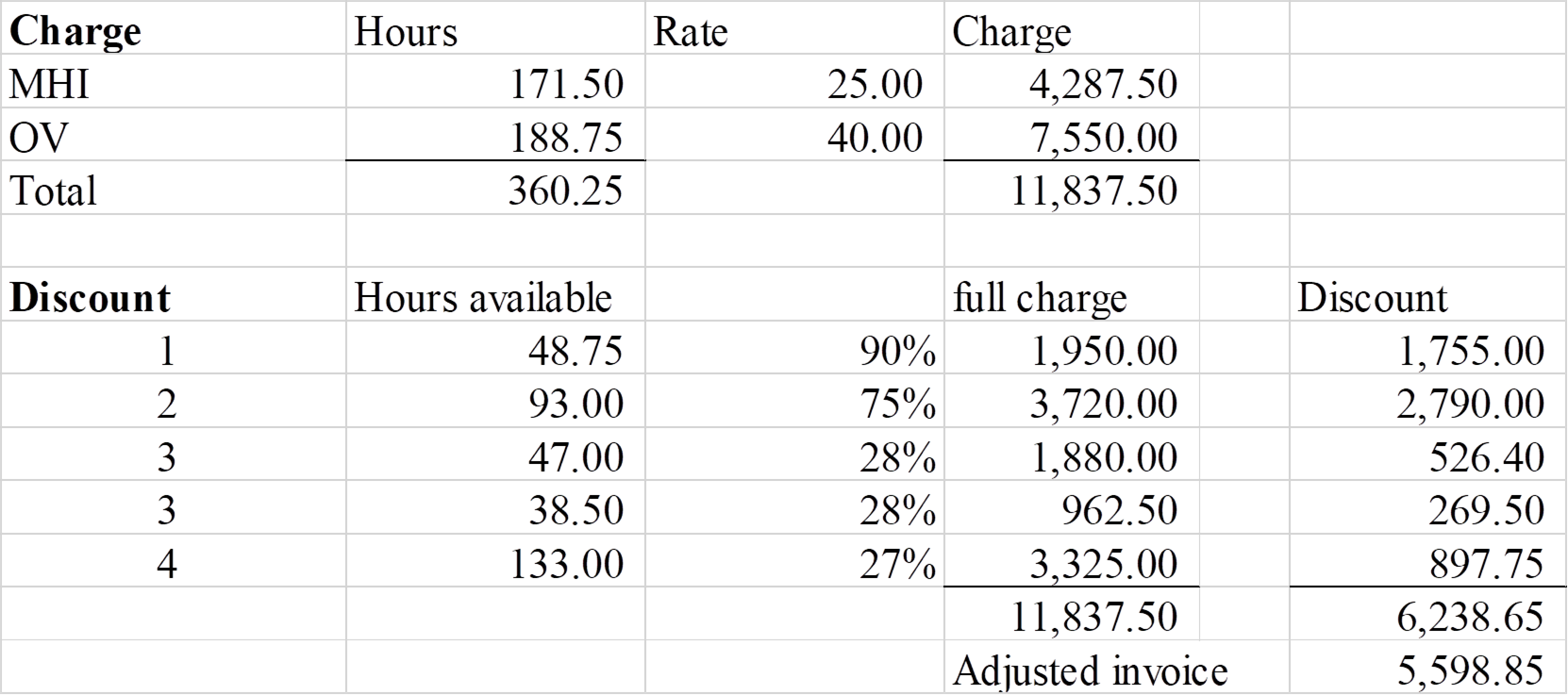

33. This shows that 171.5 hours of MHI time were supplied at £31.90 per hour and 188.75 hours of OV time were supplied at £48 per hour giving rise to a headline figure of £14,530.85. This in turn was subjected to a discount of £7,575.09 (52.13%), leading to the fee of £6,955.76. The discount operates regressively with the highest rate of 90% being given for the first 48.75 hours falling in steps to the lowest rate of 27% being given for the last 133 hours. Obviously, the discount, operating pro rata rather than pro tanto, cannot eliminate the bill. To illustrate this I set out below a reworked calculation of what the invoice would come to if, by way of example, the hourly rate for OVs was reduced to £40 and the hourly rate of MHIs reduced to £25. It shows that the bill would fall to £5,598.85, a reduction of £1,356.91.

The application for judicial review

34. A letter before action was sent by the claimants on 22 July 2021 and a response was provided on 8 September 2021.

35. By their claim form, dated 12 October 2021 and issued on 18 October 2021, the claimants sought to challenge “the defendant’s levying of certain charges, ostensibly pertaining to the performance of official controls, against the claimants, by way of invoices dated 13 July 2021”. The remedy sought was:

“An order that the invoices dated 13 July 2021 be:

· Quashed on the basis that the FSA has failed to comply with its express statutory duty of transparency and/or its duty to give reasons for its decision; and/or

· Quashed in full or to the extent that the Court determines that the charges contained in them have been unlawfully levied.”

36. By the accompanying statement of facts and grounds, the claimants sought permission relying on three grounds, namely that:

i) The FSA has not complied with its express duty of transparency under Article 85 of the EU Regulation (Ground 1);

ii) The FSA has failed to comply with its duty to give reasons for its decision to levy the charges set out in the Invoices (Ground 2); and/or

iii) The FSA has acted unlawfully by levying charges on the claimants - the relevant charges being the costs charged by E&J pursuant to the contract - which it is not entitled to recover pursuant to Article 81 of the EU Regulation (Ground 3).

37. The claim was accompanied by a witness statement from Peter Hewson, the Veterinary Director of AIMS who “has been largely responsible for liaising with the FSA on behalf of AIMS’s members in respect of the matters which are the subject of this claim”.

38. The FSA filed summary grounds of resistance dated 11 November 2021, by which it maintained that the claim was unarguable on each ground and, in any event, there would in practice be no benefit to be obtained from the relief sought. On the latter point, the FSA submitted that, owing to the discounts offered to FBOs based on the number of hours of OV and MHI time they require for official controls on their premises:

i) In respect of two of the claimants, even if all of E&J’s recoverable costs were removed, that would not lead to them being invoiced a lower sum; and

ii) In respect of the remaining claimants, the court would have to find that E&J staff costs are irrecoverable because the OVs and OAs were employed by E&J rather than the FSA.

39. As such, the FSA maintained that even if the invoices were quashed and recalculated, the invoices would not be any lower.

40. Accompanying the summary grounds of resistance was a witness statement of Richard Collier, the ‘Head of Finance - Charging’ at the FSA, dated 11 October 2021.

41. A Reply to Summary Grounds of Resistance was subsequently filed by the claimants, dated 23 November 2021. In summary two points were made:

i) The “gravamen of the present challenge” was not that the FSA is not entitled to charge to industry E&J’s costs of performing official contracts, but “the [FSA]’s failure to establish any such legal basis (having abandoned its previous justification of E&J being a delegated body)”. Three fundamental flaws were argued in respect of the FSA’s position: i) that the FSA “entirely ignores” its obligations as a matter of public law to “ensure a high degree of transparency”; ii) it fails to comply with the general public law duty to give reasons; and iii) the OVs and MHIs supplied by E&J are not ‘staff’ and therefore the costs of their official controls are not recoverable within Article 81 of the EU Regulation; and

ii) The argument of ‘no practical benefit’ is flawed in that “the purpose of the discount is not to act as a corrective to the unlawful charging of official control costs (and it would be unlawful if that was its purpose)”; the FSA is “required both to calculate recoverable charges correctly and apply any relevant discount based on the number of OV/OA hours worked” [emphasis in original]. Taking one example, it was submitted that a saving of £3,577.18 could be demonstrated.

42. On 26 November 2021, Clive Sheldon QC granted permission to the claimants on Grounds 1 and 3, and refused permission on Ground 2. The claimants have not sought to renew their application for permission on Ground 2.

43. Detailed Grounds of Resistance from the FSA followed dated 18 February 2022. A second witness statement from Richard Collier was also filed by the FSA.

44. The claimants filed a second witness statement from Peter Hewson dated 20 May 2022.

45. Further correspondence was also contained in the court bundle, comprising:

i) A letter from Roythornes Solicitors (for the claimants) to Flint Bishop LLP (for the FSA) dated 6 April 2022 inter alia requesting the make up/breakdown document of E&J’s costs for March 2021 “on the basis of which the invoices of July 2021 which are the subject of the claim were delivered”. In addition, the claimants’ solicitors sought, pursuant to an FSA email dated 26 April 2021 which they had received, equivalent breakdowns of charges for March 2020 and 14 December 2019 (when the Regulation came into effect), together with the equivalent for March 2019, 2018, 2017 and 2016.

ii) A letter from Flint Bishop LLP to Roythornes Solicitors dated 8 April 2022 stating that there is no difference between the costs included in the charge rates between March 2021 and September 2021, and refusing to provide such further requested documentation on the basis of irrelevance.

iii) A letter from Roythornes Solicitors to Flint Bishop LLP dated 25 May 2022 seeking an adjournment of the trial for this matter to be mediated.

iv) A letter from Roythornes Solicitors to Flint Bishop dated 31 May 2022 stating that:

“[O]ur clients will not be pursuing the issue in relation to “staff” at trial and we will deal with the consequences of our clients no longer pursuing this claim, either at the trial itself or any consequential hearings thereafter. Please do not take any steps to incur costs in dealing with this issue in your preparation for the trial.”

46. At the hearing before me there was some debate as to the precise meaning of this last letter. I ruled that it took effect so as to abandon Ground 3 but did not have the effect of preventing an argument being mounted that the wage bill of OVs and MHIs, whether incurred by E&J or by the FSA directly in respect of its in-house MHIs, was not sufficiently explained so as to satisfy the duty of transparency.

47. Thus, only Ground 1 was in play at the hearing.

The FSA Website

48. I now look to see what the FSA puts on the FSA website and ask myself whether it satisfies the requisite duty of transparency.

49. My overall impression is that the website is well designed, written in plain English, easy to navigate and largely complies with the duty of transparency.

50. From the home page the user navigates to Business Guidance, then to meat and slaughter, then to charging of meat premises, to arrive at the page Charges for controls in meat premises. Here clicking on Charges guide takes the user down the page to PDFs of not only the current charges guide but also of past charges guides stretching back to 2016/17.

51. This part of the page appears thus:

52. I will focus on the charges guide for 2021/22 as this is the guide that covers the invoices which are the subject of the proceedings.

53. I am not going to say anything about the charges guides before 2021/22.

54. The 2021/22 Charging Guide[10] is comprehensive and I will not attempt to set out all its detail in this judgment. On p10 it states

“How are FSA charges calculated?

Overview

12. Hourly charge rates are calculated from two main sources:

a) Direct costs of frontline staff, for example salary, employer’s National Insurance, employer’s monthly pension costs (excluding pension deficit); and

b) Support costs driven by meat controls, for example operational support to frontline staff.

13. Support costs are calculated on an activity-based costing model that has been subject to external audit.

14. There are two main elements that are used to determine FBOs’ charges:

• time based charges - detailed at paragraphs 20 to 63

• any discount available to reduce the time cost charge - detailed at paragraphs 64 to 78”

55. On page 11 it explains that:

“FSA time based charges are calculated by multiplying the time that the official auxiliary (Meat Hygiene Inspector or ‘MHI’) or official veterinarian (OV) has recorded on their timesheet to the nearest quarter of an hour, as time spent carrying out meat controls, by the appropriate hourly charge-out rate.”

56. On pages 17 & 18 it states:

“Hourly charge-out rates

60. The FSA has charge-out rates for meat controls work. These rates are calculated on the basis of the full costs, which are recoverable. For FSA time spent on meat, the FBO’s time-based charges will be calculated using these rates with any relevant discount rates applied (see paragraphs 64 to 78).

61. FSA charge-out rates are calculated each year and are made up of direct staff costs and overheads. Charge rates for allowances are also calculated each year. The details of these calculations can be found online.

62. Changes to hourly charge-out rates for meat controls are made after advance notification to industry stakeholders. The FSA will endeavour to give FBOs a minimum of fourteen days’ notice prior to any new charge-out rates coming into effect.

63. The charge-out rates are included in this guide at Annex A.”

Annex A states that the MHI rate is £31.90 per hour and the OV rate £48 per hour.

57. The guide then goes on to explain how the discount operates.

58. The user then needs to return to the page Charges for controls in meat premises and then click on Cost data and then click on the PDF Meat Hygiene Cost Data 2021/22[11]. The PDF then opens. It has 38 pages. The front page gives the title: Cost Data Slides for 2021/22.

59. Page 4 states:

“The purpose of the slides

• The presentation of the cost data for meat industry hourly charge rates for 2021/22.

• The presentation covers England & Wales.

• To clarify and provide transparency on:

- direct and indirect essential support costs of meat controls,

- process to calculate hourly rates,

- FSA application of current GB charging (including retained EU law).

• To confirm the hourly rates have been validated by independent external audit.

• All figures displayed in these slides are budgeted costs and hours.”

60. Page 7 states:

“How the meat rates are calculated

• The direct cost per chargeable hour is calculated.

• The indirect cost of meat is calculated based on data from all FSA business areas and approved by senior management.

• Only the meat related indirect cost is included in the hourly rate calculation.

• The items included in the rates are reviewed by the Head of Legal Services.

• The calculations are audited by external auditors.”

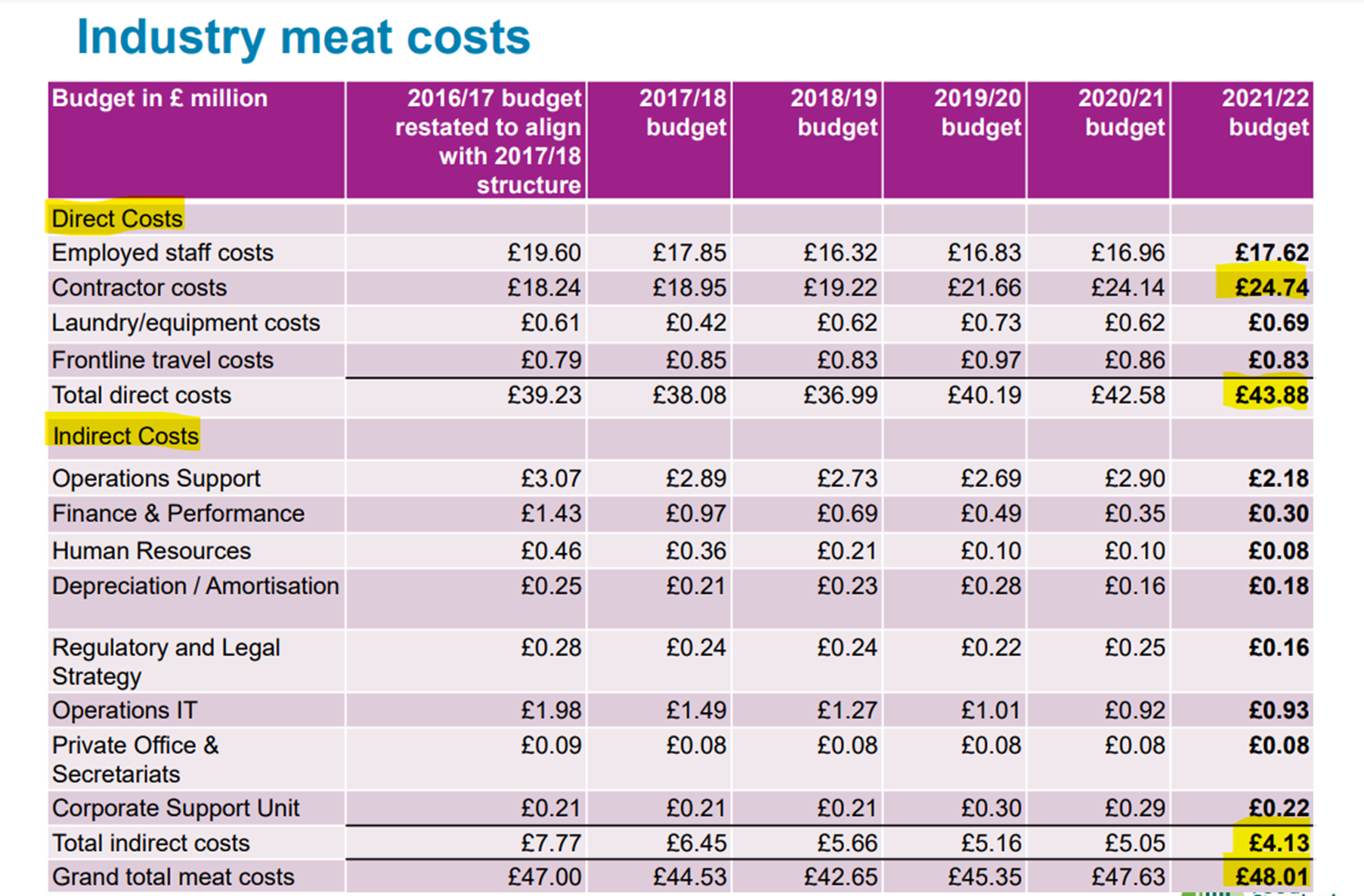

61. Page 14 is important. I reproduce it:

62. I have highlighted certain figures to which I will return. At this stage I draw attention to the overall meat cost of £48.01m which will, subject to discount, be passed on to the FBOs. Although that figure of £48.01m is broken down no explanation is given as to how the constituent parts were calculated. The “big ticket” items of employed staff costs of £17.62m and contractor costs of £24.74m are entirely unexplained.

63. I emphasise that this figure of £48.01m is the primary datum in the calculation of the hourly charge-out rates.

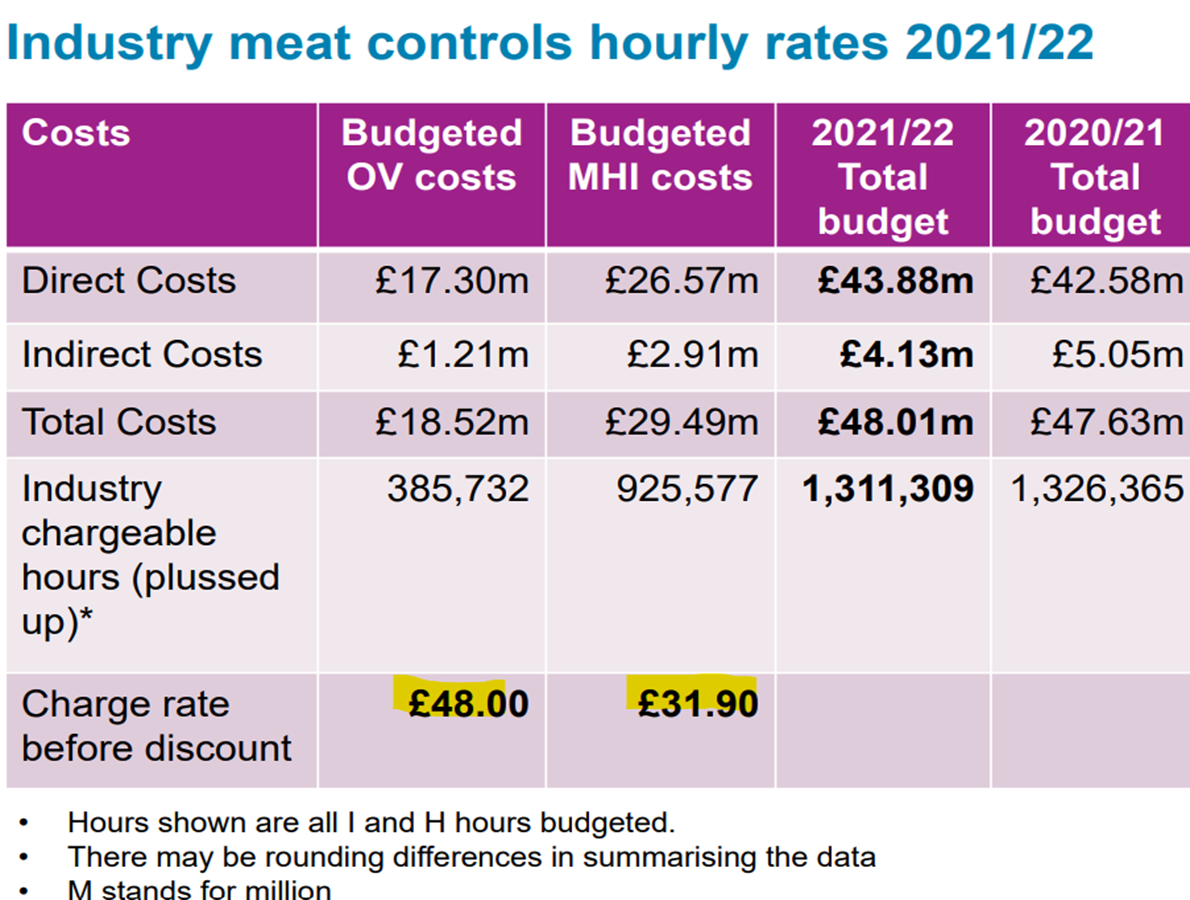

64. Page 9 is also important:

65. So, taking stock at this point, the user of the website has learned that:

i) the figure for total costs was given in the amount of £48.01m (see paragraph 61 above);

ii) that figure was broken down between direct and indirect costs which themselves were further broken down and itemised (ibid). But there was no explanation of how the itemised figures were arrived at;

iii) the total costs figure was separately apportioned between OVs and MHIs, but that apportionment was not explained (paragraph 64 above);

iv) the figures given for industry chargeable hours for OVs and MHIs were budgeted (paragraph 59 above).

66. The actual calculation of the hourly rate is not set out, but this is easily enough worked out:

|

MHI |

OV | ||

|

Total costs* |

29,480,000 |

18,520,000 |

A |

|

Hours |

925,577 |

385,732 |

B |

|

Hourly rate ** |

31.85 |

48.01 |

A ÷ B |

|

* figs at para 64 multiplied by 1,000,000 | |||

|

** slight difference to actual rate due to rounding | |||

67. In what follows I shall call the total costs ‘A’. It can be seen that in the calculation of the hourly charge-out rates there are four essential data inputs namely the MHI and OV costs (I call these ‘A1’ and ‘A2’ - their aggregate is A) and the budgeted total FBO chargeable hours for MHIs (‘B1’) and for OVs (‘B2’). The hourly charge-out rate for MHIs is therefore A1 ÷ B1 and for OVs is A2 ÷ B2.

68. As has been seen, the website gives a figure for A of £48.01m, for A1 of £29.49m and for A2 of £18.52m, but does not explain how that apportionment was arrived at.

69. It gives for B1 and B2 figures of 925,577 and 385,732 hours. A total of 1,311,309 industry chargeable hours.

70. It itemises A as follows:

· employed staff costs of £17.62m (I call this ‘A3’)

· contractor costs of £24.74m (‘A4’)

· other direct costs of £1.52m (‘A5’)

· indirect costs of £4.13m (‘A6’)

but it does not explain how these figures are calculated.

71. On page 21, Article 81 is quoted to demonstrate which costs are chargeable. On page 22 is a statement by independent accountants, Mazars, which states that in their opinion the charge rates for OVs and MHIs

“…have been calculated correctly in each model based on our assessment of the mechanics and validation of the source data to the reports provided”.

72. Page 35 explains how the figure for the total indirect costs of £4.13m was calculated. It was done by taking 91.17% of the relevant costs as being referable to the FBOs, with the remaining 8.83% being referable to the government or the FSA. No explanation for this factor of 91.17% was given. I have since been told in an email that this factor derived from the hours budget. The budgeted figure for industry chargeable hours was 1,311,309 (see paragraph 69 above). The budgeted figure for government hours was 127,060 giving a total of 1,438,369 budgeted hours. The proportion referable to FBOs is thus 1,311,309 ÷ 1,438,369 = 91.17%, and this is the factor used as the industry standard.

73. The mapping document referred to above at paragraph 26 is at page 38.

74. While the level of detail is impressive and creditable, one thing is absolutely certain. A reasonably astute reader of the website would not be able to understand how the figures A1, A2, A3, A4, A5 and A6 had been arrived at.

75. Exactly the same concerns apply to the current 2022/23 charging regime.

76. During the hearing I was given a certain amount of further information about A3, A4, A5 and A6.

77. So far as A3 (employed staff costs of £17.62m) was concerned, once I had been given the industry standard factor of 91.17% I was able to work out that the headline budgeted wage bill of all the staff working in the meat industry part of the FSA was £19.09m (17.4 ÷ 0.9117 = 19.09).

78. In the pre-trial period disclosure took place and an explanation for A4 (contractor costs of £24.74m) was provided.

79. It is by no means straightforward but I will attempt to summarise it. I have been able to do so as I have been given a copy of the Excel workbook on the level of contractor costs, the printout of which was disclosed by the FSA to the claimant.

80. The exercise was as follows:

i) The first datum is the actual tender value of the contract between FSA and E&J. That was £27,987,252.

ii) That figure is then rateably adjusted by the increase in budgeted hours over those provided in the tender (1.45%) to take it to £28,394,155.

iii) That figure is then adjusted:

a) to add proposed pay increases to OVs and MHIs in the light of the great difficulty in recruiting them from the EU following Brexit: £1,699,000,

and

b) to deduct non-chargeable items, such as (some) overheads and profit, totalling £2,525,242,

giving an adjusted figure of £27,567,913.

iv) That figure is then adjusted by a factor of 89.74%. I am told that this is an alternative industry standard reflecting the proportion of the time spent by staff doing official controls work and the proportion of the time doing other work.

v) This takes the figure down to £24.74m, which is the figure appearing in the table at paragraph 61 above.

81. The Excel workbook then goes on to distribute that figure of £24.74m between the various Article 81 headings. As explained above at paragraph 24 the first version of this had the contractor costs separately quantified in the sum of £24.74m. However, as explained above, this had to be corrected and restated in the light of the conclusion that E&J was not a delegated body. This required a complex redistribution exercise to be undertaken. Essentially, individual direct costs were re-expressed rateably. So, taking wages as an example, in the original tender these amounted to 77.85% of the chargeable total. Therefore the figure that was used for wages for the purposes of Article 81 was 77.85% of £24.74m, giving £16.62m. Using the same technique for the other permitted direct costs increased the figure to £22.87m for the overall direct costs. The overheads were then adjusted by the factor of 89.74% mentioned above. These came to £1.87m, giving the target figure of £24.74m.

82. This exercise will not be repeated now that the status of E&J has been correctly restated as being one of agent. In my judgment, the exercise was a conscientious and scrupulously fair attempt to redistribute the figure of £24.74m accurately.

83. As for A5 (other direct costs of £1.52m), it was explained to me that laundry and equipment costs of £0.63m and frontline travel costs of £0.76m were calculated by taking the budgeted figure for these items insofar as they strictly relate to the performance of official controls.

84. As for A6 (indirect costs of £4.13m) it was explained to me that the FSA’s overheads referable to the provision of official controls were calculated by first apportioning a reasonable proportion of the FSA’s overheads to the meat industry functions performed by the FSA and then applying the FSA industry percentage to give £4.13m.

85. It was only following receipt of all this information that I was able to understand how these elements of A were arrived at. I remind myself at this point that A is the primary datum in the calculation of the hourly rates.

86. As for B1 and B2 the claimant raises an issue that will be relevant for the 2021/22 charging period but not subsequently. In 2021/22 the budgeted hours for OVs and MHIs included hours spent on enforcement measures. These hours would have translated into costs charged by the FSA. The FSA has since accepted that enforcement costs cannot be recovered under Article 81 and has said that:

“For 2021/22 the FSA has separated the time coding by OVs and MHIs for enforcement from other activities. This will provide data in preparation for the 2022/23 year and the calculation of a separate hourly charge rate that covers enforcement activity.”

87. It is submitted on behalf of the claimants that the number of hours spent on enforcement thus removed ought to be given.

My decision

88. The absence of information on the website for the 2021/22 charging period about (a) the calculation of A3, A4, A5 and A6, and (b) how A was apportioned between A1 and A2, had the consequence of preventing a reasonably astute reader of the material on the website from checking, broadly, the accuracy of the calculation of the hourly charging rates. This consequence constituted a breach of the duty of transparency.

89. This breach is straightforwardly remediable. In my Order I shall direct that the FSA inserts a note into the costs data PDF file for 2021/22 presently on the website which explains in simple, clear, short, and jargon-free language how the elements of A (i.e. A3, A4, A5, A6), were arrived at, and how A was apportioned between A1 and A2. Detailed calculations will not be required.

90. The note must further explain, in broad terms, the principles that were applied to strip out non-chargeable costs. I would have thought that it was unlikely that much more would have been needed than an explanation along the lines of paragraph 72 above about the calculation of the industry standard.

91. An equivalent note must also be prepared and inserted in the costs data PDF for the for the current charging period 2022/23.

92. So, for example, I would have thought that for A3 something along the lines of the following would fill the gap:

“The budgeted wage bill of all staff who work in the meat division of the FSA is £x. From that amount the sums of £y1for pre-service training and £y2 for impermissible overheads are deducted as non-chargeable items under Article 81, leaving £19.09m. That figure is then reduced by the industry standard of 91.17% to £17.62m. See the note below about the calculation of the industry standard, which reflects the likely division of the time of staff between work done on industry matters (which is chargeable) and work done for the government (which is not).”

93. I emphasise that I do not agree that the level of detail sought by the claimant is needed to satisfy the duty. For example, in an email sent to my clerk on 28 June 2022 it was said as regards A3 (staff costs):

“The claimants maintain that the duty of transparency requires the FSA to identify the wage bill of those actually performing official controls (OVs and MHIs) as opposed to those managing them. This breakdown is, in the claimants’ contention, important for industry and the public to be able to assess the efficiency of how official controls are carried out and supervised.”

94. In my opinion the degree of detail sought by the claimants is of a scale which would enable them to conduct their own independent audit of the calculations. They are seeking a level of particularity which, in my opinion, goes far beyond that which the duty requires. Although Mr Mercer QC disavowed any intention on the part of the claimants to accrue sufficient data to conduct an audit, it is clear to me that the level sought would enable precisely such an exercise to be conducted (whether or not that is the considered intention of the claimants).

95. The grant of a remedy in judicial review proceedings is discretionary. Given that the nuclear option of a quashing order is available, it follows that, in my judgment, the greater must include the lesser and, therefore, I must be possessed of a power to make a mandatory order, of the character of an injunction, for the necessary missing information to be provided to the public in the way that I have ruled. Article 85 grants a right, and where there is a right there must be an appropriate, proportionate, remedy. In Ashby v White (1702) 2 Ld Raymond 938 Lord Chief Justice Holt said in one of the most cited dicta in the law books:

“If the plaintiff has a right he must of necessity have a means to vindicate and maintain it, and a remedy if he is injured in the exercise or enjoyment of it.”

96. I do not order that those details of the enforcement hours included in B1 and B2 need be given. I accept McGurk’s argument in paragraph 44(a) of his skeleton, where he stated:

“Therefore if 100% of the costs are included, so are 100% of the hours. If 10% of the hours were for enforcement activity, then if 10% of the cost and 10% of the hours were removed from the costs included for official controls, that would leave 90% of the cost and 90% of the hours. Stripping both out of the calculation of the rate for official controls would leave an identical hourly charge as the budgeted cost and budgeted hours are reduced in identical proportions: 1000 divided by 100 gives the same rate as 900 divided by 90. So even though enforcement costs were included within the calculation of the rate for 2020/21, it is precisely because (i) the rates for official controls and enforcement activities were identical and (ii) enforcement costs were only raised against individual operators subject to enforcement action, that the inclusion of enforcement activities within the calculation of the official control rate made absolutely no difference to that rate in 2021/22. And the Claimants no longer contend to the contrary having seen the evidence.”

I cannot improve on that.

97. Nor am I prepared to order the FSA to place on the website a calculation of official control activities with reference to the activity codes, as sought by the claimant. If I understood the argument correctly, it is suggested that given the revelation of the inclusion of enforcement time, such an exercise may well expose that the time spent on other non-chargeable activities has been wrongly included in B1 and B2. There is no evidence to support such a suspicion and, even if there were, I cannot see why Mr McGurk’s riposte would not apply equivalently. In my judgment, my decision that the note must explain in broad terms the principles applied to strip out non-chargeable costs is amply sufficient to enable a member of the public to understand how the relevant costs are calculated and passed on.

98. I am not prepared to award any further relief beyond such an order. It is completely pointless to quash the invoices in circumstances where I suspect that the process I have set out above will in all likelihood confirm the accuracy and legitimacy of the current hourly charge-out rates. Nothing in the evidence thus far has demonstrated to me that it is more likely than not that fundamental errors, let alone skulduggery, have infected the calculation of the hourly rates. However, that is beside the point. The point is that the member of the public (to whom the FSA is accountable) reading the website is not given sufficiently clear information about A, the primary data input for the calculation of the hourly charge-out rates, to enable the accuracy of those calculations to be broadly checked.

99. During the hearing I circulated some proposals for a note to be included within those PDFs on the website. However, on reflection, I think it is probably unwise for lawyers and judges, accustomed to speaking in a language which is some distance away from the standards of plain English, to be drafting these notes. I leave it to the parties to agree the terms of these notes; if they cannot do so I will rule on any dispute.

_________________________________

[2] By section 3 of the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018,

[3] By The Official Controls (Animals, Feed and Food, Plant Health etc.) (Amendment) (EU Exit) Regulations 2020.

[4] See regulation 3(1)-(2) of The Official Controls (Animals, Feed and Food, Plant Health Fees etc.) Regulations 2019 and Schedule 3 of the Official Feed and Food Controls (England) (Miscellaneous Amendments) Regulations 2019.

[5] Defined as “a veterinarian appointed by a competent authority, either as staff or otherwise, and appropriately qualified to perform official controls and other official activities in accordance with this Regulation and the relevant rules referred to in Article 1(2)” (Article 3(32).

[6] Defined as “a representative of the competent authorities trained in accordance with the requirements established under Article 18 and employed to perform certain official control tasks or certain tasks related to other official activities” (Article 3(49)).

[7] In England an OA is designated as a Meat Hygiene Inspector (“MHI”).

[9] The typo giving the year as 2012 was corrected in a witness statement.