Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

England and Wales High Court (Administrative Court) Decisions

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> England and Wales High Court (Administrative Court) Decisions >> LPHCA Ltd (t/a Licensed Private Car Hire Association) v Transport for London (TfL) [2018] EWHC 1274 (Admin) (30 May 2018)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Admin/2018/1274.html

Cite as: [2018] EWHC 1274 (Admin)

[New search] [Help]

QUEEN'S BENCH DIVISION

ADMINISTRATIVE COURT

Strand, London, WC2A 2LL |

||

B e f o r e :

____________________

| LPHCA LIMITED t/a LICENSED PRIVATE CAR HIRE ASSOCIATION |

Claimant |

|

| - and - |

||

| TRANSPORT FOR LONDON |

Defendant |

____________________

MR TIMOTHY STRAKER QC (instructed by TRANSPORT FOR LONDON) for the Defendant

Hearing date: 25 April 2018

____________________

Crown Copyright ©

- Transport for London, TfL, is the Greater London licensing authority for hackney carriages, usually called taxis or black cabs, and their drivers, and for private hire cars, licensing their operators, drivers and vehicles. It charges fees for the application and grant of each of those five different forms of licence. TfL decided in August 2016 that it needed to employ 250 compliance officers for its compliance and enforcement work in relation to those licensable activities, making a total of 332 compliance officers, plus the existing 50 support staff. This increase in staff numbers had to be paid for out of the fees charged for the licences. At the same time, the existing fee structure for private hire operators' licences was to be re-examined. In April June 2017, TfL carried out a consultation on those fee changes so far as they affected private hire operators. This was the only group of licensees significantly affected by the changes.

- The Claimant, the Licensed Private Hire Car Association Ltd, is a national association of private hire car operators, with some 200 members. In London there are some 2400 such operators. It responded to the consultation, complaining about the lack of financial information made available, and objecting to the changes. On 18 September 2017, the Finance Committee of TfL decided to make changes to the fee structure for private hire operator licensing, with some amendments to those originally put forward in the consultation. That decision was given effect through the Private Hire Vehicles (London) (Operators' Licences) (Amendment) (No.2) Regulations 2017, the Regulations.

- The Claimant challenges the decision and the Regulations on two bases: (1) the consultation process was unlawful because TfL failed to provide adequate information to permit of an informed response on the financial basis for the changes; whether the information was adequate or not rather depends, as the arguments evolved, on what the true scope of the consultation was; (2) the apportionment of additional costs to private hire operators, rather than more to taxis, and to private hire drivers and vehicles, was unlawful because it involved a cross-subsidy from private operators to other licensees; the issue was whether such a cross-subsidy in fact was created. It was not at issue but that a cross-subsidy would have been unlawful.

- Permission was granted to argue those two points by Dingemans J at an oral hearing. He refused permission to argue other grounds of challenge to the consultation process such as inadequacy of time and inadequate consideration of the responses, and to the changes to the fee structure, notably bias and irrationality.

- The main legislation is the Private Hire Vehicles (London) Act 1988. Ss 1,2 and 3 deal with the requirement to hold an operator's licence, and the application for such a licence. An operator's licence is required for inviting or accepting private hire bookings. An operating centre is required. The licence may be granted subject to prescribed conditions and to others which the licensing authority thinks fit. The operator must be a fit and proper person to hold such a licence; s3(3). S4 sets out the obligations on a private hire operator; chiefly, any vehicle provided by him for a private hire booking must be a vehicle in respect of which a London PHV licence is in force, and must be driven by someone who holds a London PHV driver's licence, or cab driver's licence. The other obligations, as Mr Matthias QC for the Claimant pointed out, are obligations which are fulfilled at the operating centre, rather than on the street: display of the operator's licence, keeping records of bookings with the required particulars,and records of the vehicles and drivers available to the operator. The drivers are usually self-employed, and are allotted jobs by operators for whom they work. Ss 8, 12 and 13 provide for the licences for private hire vehicles and private hire drivers. Licences can be suspended or revoked if, for example, the authority ceases to be satisfied that the operator is a fit and proper person to hold such a licence; s16.

- There are therefore three forms of licence in the private vehicle hire licence system. For each form of licence, by s20, TfL "may by regulations provide for prescribed fees to be payable (a) by an applicant for a licence ;(b) by a person granted a licence ." S32 permits regulations to be made for the purpose of prescribing anything which is to be prescribed, and may make different provision for different cases. This language is different from that to be found in the Town Police Clauses Act 1847, as supplemented by the Local Government (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1976, governing licensing for hackney carriages and private hire vehicles outside Greater London. This refers to charging such fees as the licensing authority considers reasonable to recover the costs of issuing and administering the system, which includes the control and supervision of hackney carriages and private hire vehicles. But the Parliamentary intention is the same, neither broader nor narrower.

- The main Regulations are the Private Hire Vehicles (London) (Operator's Licences) Regulations 2000, which the 2017 Regulations at issue amended. They give no indication as to the basis upon which fees are to be calculated.

- There is no statutory provision for any consultation about fee levels or fee changes, let alone about the budgetary process or financial assessments which may underlie them.

- I also need to mention the two other licensing strands, for which fees may also be charged. These are for the licensing of black cab or taxi drivers and of their vehicles, hackney carriages. The relevant powers are in the Metropolitan Public Carriage Act 1869, and its amendments.

- Their licensing is relevant because the licensing, compliance and enforcement tasks and costs for black cabs and private hire vehicles overlap to a very large extent, and form part of the argument about cross-subsidy. The Claimant is concerned that, as well as private hire drivers and vehicles, the black cabs and their drivers are being subsidised by the effect of the increases in private hire operator licensing fees.

- As I have said, it was not at issue but that the fees charged for operator's licences could not lawfully include any element of cross-subsidy whether for private hire vehicles or their drivers, or for black cabs or their drivers. The same principle applied across the five strands of fees; it was not peculiar to operators' licence fees. I regard that as correct, though the case law is quite thin.

- Plain it is that fees can cover more than the costs of the administrative process in considering and issuing licences; see R (Hemming) t/a Simply Pleasure Ltd v Westminster City Council [2015] UKSC 25, in the context of sex shop licensing, where the statute required the applicant for a licence to "pay a reasonable sum determined by the appropriate authority" , which permitted fees to be set at a level to cover the running and enforcement costs of the licensing scheme. The different language in this case plainly still permits fees to be set at a level to cover the running and enforcement costs of the licensing scheme. Equally plain it is that there is no power to prescribe the level of fees in order to exploit the market; see R v Manchester City Council ex parte King (1991) 89 LGR 696 D Ct; the power to charge fees for street trader licences was "such fees as [the district council] consider reasonable for the grant or renewal of a street trading licence." This covered the total costs of operating the scheme, including enforcement and prosecution. But it did not permit the council to charge fees by reference to what it thought the market would bear.

- The agreement that fees from one taxi or private hire licensing strand cannot be used to subsidise the level of fees on another of the five strands is reflected in a considered concession by leading counsel, accepted by Hickinbottom J in R (Cummings) v Cardiff City Council [2014] EWHC 2544 (Admin) at [7].

- In my judgment, there is no power to use the fee charging provision in order to act as a market regulator. A cross-subsidy would be a form of market regulation, which the licensing system cannot be used to achieve, in the absence of an express power. There is no power to refuse a licence because an authority might wish to encourage black cabs over private hire or vice versa, or because there were so many drivers and vehicles that fewer made a living than was thought desirable. The fee structure cannot be used to the same end, as between black cabs and private hire.

- Nor can the licensing system be used to raise revenue from one strand of private hire licences to favour another strand of private hire licences, say, to favour drivers over operators: it would be unlawful to structure licence fees on the basis that all the costs of enforcement should be borne by operators and not by drivers, for whatever reason, or to appeal to some imagined public sentiment about who should pay. And by the same logic, the simple words of the Act mean that the contribution of the operators of varying sizes must equally avoid cross-subsidy from the larger ones to the smaller ones or vice versa. The fee contribution to the overall costs attributable to private hire licensing, including compliance checks and enforcement, must on that same basis be apportioned to operators, drivers and vehicles in some manner, where perfection is not attainable, which reflects their respective contributions to the costs.

- This is all inherent in the statutory language enabling fees to be charged for the application for and grant of a licence, and the basis upon which such applications may be refused. It is a licensing function, not a competition or market regulation power, or one which permits one form of operator or driver or vehicle to be favoured over another, or to favour drivers at the expense of operators on the grounds, stated or implied, that one but not the other may be a corporate body. Still less is it a revenue raising power.

- I emphasise these points because cross-subsidy is at the heart of both grounds: was information required about how the costs were apportioned as between all private hire licence fees and black cab licences fees, and between operators' fees and other private hire licence fees? Was there in the upshot a cross-subsidy from operators to others?

- The press release introducing the consultation document dated 20 April 2017 introduced the changes to operator licence fees, in a way which conveniently summarises the background:

- The consultation paper itself introduced the issue this way:

- It then said under the heading "Licensing administration and compliance costs", before providing a table similar to the table above:

- The Claimant raised a number of issues, including about the information available, in correspondence with TfL. Its on-line response, following the on-line template, stated:

- The officer report of 15 September 2017, to the Finance Committee, chaired by Ms Val Shawcross, Deputy Mayor for Transport, whose comments elsewhere were also deployed by Mr Matthias on the cross-subsidy issue, itself attracted no adverse submission from Mr Matthias. It dealt with the outcome of the consultation. The costs of the licensing and enforcement regime were not at present being met in full from the fees it raised. The summary continued:

- The main text of the report set out the background, much as in the consultation paper. It pointed out that in Spring 2015 an extensive consultation process on the private hire industry had taken place, the second stage of which proposed a review of the current operator licence structure, to which the TfL Board had agreed in March 2016.

- The report then summarised the "main relevant comments" from the consultation: the fees proposed would make businesses unviable, and there should be more tiers or at different vehicle numbers. A cap on private hire vehicle numbers and "a number of other suggestions" were outside the scope of the consultation. Many respondents were private hire drivers and customers. 345 were private hire operators. The Claimant's response was specifically mentioned in the Appendix on the consultation results.

- The various suggestions were dealt with: a single fee for each vehicle, some means of reflecting the compliance record of the operator, additional tiers, "increasing fees for private hire drivers and vehicles instead of for operators".

- I refer to this specifically because Mr Straker submitted that one measure of what the scope of the consultation was, was how people had responded to it, and their response had been considered. This issue of apportionment of costs between operators, drivers and vehicles, as well as taxis, was where Mr Matthias principally submitted that insufficient information had been available; and it underlay the cross-subsidy argument.

- It concluded under "Financial Implications":

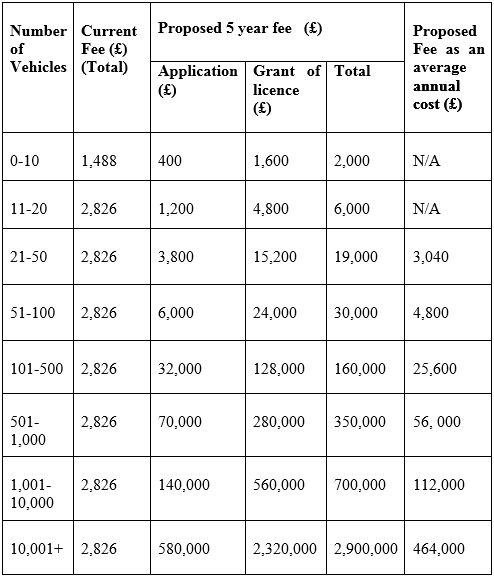

- Appendix 2 set out the proposed fees for drivers and vehicles, taxis and private hire cars. The final proposed operators' fees, which were separated into the fee for the application for a licence and the larger fee consequent upon its issues were tabulated as follows:

- I need also to refer to a page within Appendix 2, headed "Methodology for forecasting and apportioning", since this issue is at the heart of the arguments about the adequacy of consultation information and cross-subsidy.

- Directly allocated- specific costs such as vehicle inspections, topographical assessors, Knowledge of London examiners, and directly focused marketing spend etc

- Activity based apportionment- service provider costs, driver medical costs, and document archiving etc. apportioned based on expected volume trends

- Staff time apportionment- non-specific staff time is apportioned by role based on the specific activities carried out. This apportionment is then applied to salaries and on-costs to calculate a weighted average per team and also an overall weighted average.

- Overhead apportionment- based on the appropriate staff time weighted average or activity based apportionment.

- £28.3m- 30 per cent of compliance and enforcement costs, primarily staff time, have been allocated using staff time apportionment.

- £4.7m- nine per cent of licensing and policy staff costs have been allocated using staff time apportionment. Services included relate to processing licence applications, licensing support, licensing policies and standards, contracts management and business support.

- £1.0m- eight per cent of TfL overheads such as accommodation, legal and HR have been allocated using overhead apportionment (i.e. headcount and staff time weighted average rate)

- £0.7m- 11 per cent of contact centre, complaints and appeals staff costs have been allocated using staff time apportionment.

- £0.3m- one per cent of service provider costs have been allocated using activity based apportionment (i.e. active licences)."

- The recommendations were accepted, a decision notice was sent out, and the Regulations were amended to reflect the changes. The statement said that the changes would "ensure the licence fee structure for private hire operators reflects the costs of compliance activity according to the scale of each operator. Licensed drivers had increased from 65000 in 2013 to 116000 in 2017, and vehicle numbers from 50000-88000 over the same period." It also set out the changes to vehicle and driver licence fees for black cab and private hire. The black cab vehicle fees for a successful application were unchanged; the black cab drivers' fee went up from £272 to £300, the private drivers' fees from £250 to 310 and its vehicles from £100 to £140.

- There was no dispute on this. Though there be no statutory obligation to consult, yet if an authority has decided to consult, its process of consultation must be fair in order for the decision which rests upon it to be lawful. The most recent authority on what is required for a consultation to be fair is R (Moseley) v London Borough of Haringey [2014] UKSC 56: at [25] Lord Wilson said:

- Mr Matthias submitted that the Claimant had asked for information which was essential for its consultation response to be informed. In a series of answers, that information had been refused. Accordingly, its response had not been informed, and the outcome had been unfair. Once the Claimant saw the consultation document, it had written to Ms Chapman asking for further information. She was then the General Manager of the Taxi and Private Hire Department of TfL. On 4 May 2017, Mr Wright of the Claimant wrote raising a number of complaints about the consultation process which had just got under way. He asked for "clear background information on its grounds for these proposals. It would in particular be beneficial for TfL to disclose the costs deficit of (or planned future expenditures for) licensing, compliance and enforcement that necessitate these fee increases." She replied on 19 May that the purpose of the consultation was to seek comments on the changes proposed to "London private hire operators' fees so that going forward they reflect the costs to TfL of operator licensing, regulation and enforcement." To this, Mr Wright replied on 2 June seeking disclosure of "the specific cost details justifying it proposals."

- The Claimant made what it described as a formal complaint about the consultation process raising 7 issues, none of which arise now, and an eighth about what it saw as the limited disclosure of the basis for the proposals, essentially repeating what he had written earlier. Ms Chapman's reply of 3 August 2017 to the complaint said that TfL believed that it had given "sufficient details of the costs deficit and planned future expenditure."

- The reply on the information sought, to which Ms Chapman had said TfL would respond separately, came in a letter from the body dealing with TfL's Freedom of Information requests. The letter dated 4 July 2017 post-dated the closure of the consultation. It did not actually add anything which was not already available in the public domain, simply signposting the Claimant to online material which was part of the consultation process. Nothing of any substance was forthcoming in further correspondence. Ms Chapman repeated the purpose of the consultation as being what she had set out in her 9 May letter. The Claimant's reply of 2 September 2017 asked where the additional revenue was going to be spent: "Specifically, we need confirmation that the increase in licensing fees will not be used to fund street enforcement and compliance of the taxi industry". It would be unreasonable for PHV operators to pay for the regulation of taxis when they did not incur the same level of fees. On 6 September 2017, it repeated its concern that the overwhelming majority of London's private hire operators were very compliant, that the proposals were unreasonable, and it was concerned that the private hire operator licensing fees might "be used for ensuring the compliance of private hire drivers and vehicles." The funds raised through operators should only be used for regulating operators, and not to fund enforcement and compliance in its direct competitors, the taxi industry.

- Ms Chapman's evidence on the scope of the consultation included this:

- It did not consult on the costs of administering the licensing and compliance services, or on its financial projections, the costs of hiring the staff or the methodology used to reach "that figure", which I take to mean the budget figure. It was not consulting about the £209m figure and respondents required no further information on it but, she continued, at [66]:

- In my judgment, the question of whether sufficient reasons were given for the proposals to permit respondents to give intelligent consideration to them and to respond, depends on what the scope of the consultation was. As the consultation document makes clear, it was not about the hiring of 250 compliance officers nor about the £209m budget for licence and compliance costs over the next five years. It did not directly relate to taxi licence fees, nor to the fees charged to drivers or in respect of vehicles. Although those aspects are referred to in the consultation paper, and are part of the background to the changes, to enable consultees to see the context in which the proposals are being made, they are not themselves the subject of the consultation. No justifiable complaint can be made that no further information was provided about the total £209m or about taxi or driver or vehicle licence fees as such. The Claimant had also sought information in a very general way. Indeed, the Claimant's information requests seemed to focus on the wider justification for the increases to the budget rather than on the specific issue of the two stages of apportionment, first to private hire, and second to private hire operators.

- The consultation on the other hand was clearly about the proposed changes to the fee structure for operators. But the complaint was not that there was insufficient information about the tiering. The sum which the new structure was intended to raise from operators was known. This is £38m, made up of £8m (operator licensing administration costs) and £30m (TfL enforcement costs) over a five year period. That is the figure set out in the TfL consultation paper. Information was not sought about whether those tiers would raise that sum.

- The essence of Mr Matthias' submission however, was that there was insufficient information about how that £38m, apportioned for recovery through the operators' fees, and the £30m in particular, had been arrived at. The consultation paper set out the £38m figure with a short explanation that 85 percent of costs had been apportioned to the private hire trade, and a further apportionment had taken place to reach £38m for operators. How and on what evidential basis that had been done was not spelt out, although the arithmetic is obvious enough. He submitted that what Ms Chapman provided in her witness statement should have been provided for the consultation. It is perfectly clear that the consultation process did not provide any information about Tf'L's thinking to which a consultee could have responded, whatever a consultee's own methodology and estimates could have put forward. The response from TfL was that there was no need for it to have provided such information because that is not what the consultation was about. It is in that respect that the scope of the consultation is therefore at issue. Was £38m a given input, with consultation confined to how it should be raised from operators, or was the exercise of apportionment which yielded the £38m figure also an issue being consulted upon?

- The consultation paper states that it is on "proposals to change the fees private hire operators are charged for the costs of licensing, compliance and enforcement activity." The proposals would alter the only distinction in the current fee structure for private hire operator licences, which was between operators with up to two vehicles and operators with more than two, in fact even up to a thousand and more, to a more graduated structure. The increase for some would be substantial, and so the possibility of payment by annual instalments of the five-year fee was also for consultation. The proposed tiers with their fees were set out. The paper said that TfL "now invite comments on our proposed changes to the fee structure." The purpose of the consultation was to invite comments on "our proposals for changes to the London private hire operator's fees so they accurately reflect the costs of TfL of administering and enforcing a high quality service." Respondents were also invited to comment "on any aspect of the proposals" or to make other suggestions, and were "invited to provide evidence relevant to issues or proposals that are discussed."

- The three specific on-line response template questions are all about the structure of the fees for private hire operators and annual instalments. There was a further question seeking any further comments.

- There are passages in the consultation paper, notably in the invitation to comment on "proposed changes to the fee structure" and to add comments or suggestions seemingly at large which could, particularly if taken out of context, suggest a more broad ranging consultation than Mr Straker submitted was the case. However, I am satisfied that reading the consultation paper, and the on-line template response form, that the scope of the consultation was the narrower one for which he contended.

- First, that is how the more specifically worded passages in those two, and crucial documents read: I have set them out. They are concerned only with operators' licence fees and only with how they should be structured to avoid the unfairness of the simple two tier band and provide the sum which TfL has decided is what operators should pay to reflect the costs fairly attributable to operators in the running of the licensing system as a whole, including enforcement and compliance. The more specific language should be given weight over the more general, but truncated, language.

- Second, no real weight can be given to the fact that more general comments were invited, particularly in the on-line template. That is a sensible enough counterpart to "yes/no" style specific questions, which may not be the place for relevant qualifications. It would be hopeless to try to argue that this meant that TfL were consulting on all aspects of whether to have 250 more enforcement officers, their costs and budget and who should pay and why. Yet if it is not so wide, it is difficult to see that it is wider than Mr Straker contends yet narrow and precise enough to include but then stop at a consultation on how the apportionment to operators' licences was carried out.

- Third, I can see why TfL might want to give operators an opportunity to comment on major changes to the basis upon which their fees are assessed, as well as the increase in enforcement costs which they might have to meet. But I see nothing in that, or anything else, as showing that TfL intended a consultation on how it reached the £38m figure. It consulted on the structure whereby operators' fees would raise that sum.

- Fourth, the fact that TfL must have done some work on apportionment between taxis and private hire licences, and then between private operator, driver and vehicles streams, in order to reach the £38m figure cannot of itself mean that those workings were to be consulted on. Ms Chapman's evidence does not say that no such calculations had been done before; it implies that they had been, [81]: "Further work was undertaken internally within TfL to consider the financial modelling and assumptions behind the revised operator fees." Indeed, when it comes to judging what the scope of the consultation intended by TfL actually was, the fact that it did not provide that sort of information, when it otherwise should have done were Mr Matthias correct, affords some support to what I have concluded the true scope of the consultation actually was.

- Finally, although Mr Straker invited me to consider the consultation responses as some indication of what the scope of the consultation was, I found little help either way. The Claimant's on-line response is in part not couched in terms specific to the apportionment issue behind the £38m, referring instead more generally to the grounds for the increase remaining unsubstantiated and without any justification being presented. That could cover this apportionment, but certainly ranges more widely.

- Its response later says that the Claimant had sought unsuccessfully to obtain from TfL information about operator compliance costs, stating that operator licensing fees must not be used for compliance purposes in relation to other licensees. That does raise the issue of apportionment. Other consultees said that licence fees for drivers and vehicles should be increased instead; there is a section in the September 2017 report to TfL's Finance Committee dealing with the "main relevant comments" which specifically deals with that. It does not itself state that such an issue falls outside the consultation process, but explains how operator enforcement and compliance costs are not confined to the costs of specific visits to operators' premises but arise out of and are part of the on-street inspections and checks of vehicles and drivers. There is nothing else in the September report which could support a wider view of the scope of the consultation.

- I consider that it would be a mistake to see those comments and TfL's response in the September report as showing that the consultation was intended to cover the basis on which £38m was apportioned to operators, particularly in the light of the first point I have made on the language of the consultation paper and on-line response template. This general comment made by operators is a perfectly understandable one for many to have made, particularly with the limited financial information as to costs and apportionment. But it does not really help with what the consultation was actually about. Likewise, the fact that it was dealt with as a "main relevant comment", rather than as a common but irrelevant one, is not a sufficiently persuasive point in the light of the others I have referred to. It was seen as a comment which merited mention and explanation in a report, so that the decision-makers would understand the position in response to such disquiet as was expressed.

- Besides, I can understand why the operators' suspicions as to what TfL was up to had been aroused by the comments of the Mayor in the press release I refer to at the start of the second issue. Officers may have thought it necessary to explain, but not in so many words, that what could have been the expression of an unlawful stance from the Mayor, was not in fact being implemented.

- Overall, I have come to the conclusion that the true scope of the consultation, intended by TfL, did not cover the way in which £38m was the costs of licensing regime attributed to operators, and was confined to the structure whereby operators' fees would raise that sum. Accordingly, there was no unlawful failure to disclose the information about how that was worked out, in order for consultees to be sufficiently informed about the proposal actually under consultation in order to make an informed response. This ground of challenge fails.

- I start with a press release of 7 August 2016 issued by TfL, whose Chairman is the Mayor of London, of which Mr Matthias made understandable use on the unlawful cross-subsidy issue, and which left Mr Straker with some uncomfortable questions. The Mayor announced the increase in the number of compliance officers, "tackling illegal taxi and minicab activity" so that Londoners felt safe when using taxis and minicabs, to be in place by September 2017: they would:

- There were TfL internal emails of June 2016 which emphasised the desire of some not to "clobber" drivers, with others making the point that operators were to bear the "lion's share" of the cost, and that the true cause of the need for more compliance work was the rise in the use of private hire vehicles.

- The Surface Transport Board in TfL, in August 2016, referred to the Mayor's announcement; its agenda said that the new compliance officers "will be funded through TPH Operator Licence Fee Income", and later repeated precisely that point. Discussions, it said, were ongoing. However, the comment in the officer recommendation to the Board was that the costs "will be fully recovered via the taxi and private hire licence fees." This is quite different. Ms Chapman says, in her witness statement, that the Board noted that latter point. That I do not doubt, but I do not know what it decided or approved. There clearly had been some debate about that issue from at least June 2016 onwards.

- Department of Transport statistics for 2017 to which Mr Matthias referred me showed that there were 108700 licensed vehicles in London in 2017, an increase since 2015, with a decline in taxis, but an increase in private hire vehicles, with a marked increase for 2013 onwards, to reach 87400 by 2017. There were 117700 licensed private hire vehicle drivers, an increase since 2015, with a decline in taxi drivers licensed, and the number of licensed PHV operators had declined to 2400. Mr Matthias drew a comparison between that number and the total of other private hire licences, drivers and vehicles, which amounted to some 205000. Only 1.17 percent of all licences were operators' licences.

- Mr Wright, the Claimant's Managing Director and Chairman, gave evidence disagreeing with much of what TfL had decided over enforcement, but his factual evidence was quite limited on the cross-subsidy issue actually before me. He pointed to this increase in the number of private hire vehicles and drivers, and the contraction in the number of operators, to support his contention that TfL were seeking to fund the costs of enforcing the obligations of driver and vehicle licence holders through the fees for operator licences. The approach to the apportionment of costs to taxis and to the driver and vehicle licence holders in the private hire trade, as set out in the September 2017 Finance Committee report (and which he said should have been available for the consultation), had later changed. The assessment of the booking system was now simple, as generally were other compliance assessments which had to be done. Major compliance problems from operators were rare, as were compliance problems with the booking system. On-street compliance was costly for taxis as they had no operator system, so on-street checks provided the only way of testing their compliance. In his second statement, Mr Wright referred to TfL's evidence that, in the last quarter of 2017, it had carried out 36000 checks on licensed private hire drivers and nearly 43000 checks on licensed private hire vehicles, compared to only 1135 checks on private hire operators, 87 percent of whom were found to be compliant, and 9 percent of those found non-complaint were not trading. Yet TfL was now receiving more in fees and from fewer operators.

- Mr Burton, TfL's Director of Compliance, Policing and On-street Services, gave evidence about how the operators' fees had been calculated. On 25 July 2017, a TfL meeting decided to review the current and proposed deployment of compliance officers so that TfL could determine the proportion of time spent on the five individual licence streams. This concluded that the costs should be apportioned 20:50:30 to operators/vehicles/drivers. The rationale was that the average on-street inspection took 20 minutes, involving a number of checks which could be apportioned to each of the three private hire licence streams.

- Ms Chapman gave more detailed evidence. Much of it related to the justification for the recruitment of the 250 compliance officers, the lawfulness of which is not at issue. She referred to the increased number of checks which were now being carried out, and the higher compliance rates now found. Noteworthy for this litigation was the 81% increase in private hire operator checks to 461 over a four week period towards the end of 2017, compared with a 137% increase in checks of private hire and taxi drivers and vehicles, over the same period, to 26510 on-street checks.

- She pointed out that the cost of the licensing regime included back office costs, accommodation costs, IT hard and software, compliance officer costs, and Knowledge of London examination costs. The financial aim was to break even on a yearly basis with any deficit or surplus carried over to the next year. There had been a surplus in 2015-16, but a deficit in 2016-17 because of the increased costs of compliance officers. The hiring of a significant number of new compliance officers would have made the projected increase in costs clear to consultation respondents.

- Ms Chapman's evidence about how the costs of enforcement and compliance arose is critical here. Licence conditions were intended to provide confidence to those using the services of London private hire operator that it was "an honest, professional organisation with safe drivers and vehicles." Operators were required by licence conditions to have public liability insurance, to agree or estimate accurately the fare for the journey booked, provide details of changes to its operating model and of information provided in the licence application, inform TfL of the details of the dismissal of drivers whose conduct as drivers is unsatisfactory, have a complaints procedure and records, maintain a lost property system, a fare structure which was to be used, provide weekly particulars of drivers and vehicles available for bookings or used for bookings within the maximum permitted by the licence, together with any operator specific conditions.

- Ms Chapman said that the "vast majority" of compliance activities had "operator involvement", in addition to the specific operator checks. The latter entailed inspections on a licence application, or to vary a licence, and planned or unannounced compliance inspections. Unannounced inspections occurred in response to the provision of information required by the operators, or intelligence or on-street actions, identifying possible non-compliance by an operator. Operators might also be contacted during on-street vehicle and driver checks to ascertain information, such as the booking or fare agreement, and to verify driver information or vehicle maintenance records, who the driver is working for, and insurance cover. Other operator-related work included "reassurance visits" as part of the patrol of an area, patrols where operators were licensed in particular venues such as nightclubs and bars to ensure that bookings were made inside the premises, and that the nearby drivers worked for that operator, rather than loitering for unlicensed hire. Ms Chapman said that this type of work used up many hours of compliance officer time. The management of operator activities at night time venues where operators worked within the premises posed "particular challenges", where combined operator, driver and vehicle checks were undertaken. The compliance officers also deployed to supermarkets where operators had a free phone to ensure that there was no unlicensed plying for hire. Test "purchases" were carried out on operators, licensed or unlicensed.

- With those points in mind, Ms Chapman then explained how, after the consultation, the private hire operators' licence fees had been calculated, with the further tiers accepted. Mr Straker explained that the reason Ms Chapman's evidence did not deal with work undertaken earlier than August was because this second issue was confined to what the "cross-subsidy" position was in the amending Regulation. Her evidence related to that, and did not need to go back earlier. The consultation issue was about scope, and not the quite different issue of whether the figures in the amending Regulation involved any cross-subsidy. Whether cross-subsidy was involved mattered in relation to the actual framework now in the Regulations as amended.

- The post-consultation work drew upon the following methodology:

- The same approach was adopted for the series of iterations, which she described in this way, using the figures agreed on 22 August 2017:

- These figures were changed from earlier ones, which had had an 80:20 split between private hire: taxi on-street compliance costs, and an equal three-way split of on-street private hire compliance costs. The later 85:15 split at step (i) was based on a survey (post consultation) of time spent on on-street enforcement/compliance activity versus operator centre inspections. This had shown 11.4% of total compliance officer time was spent on operator inspections, but 15% was taken in view of the increase in the number of compliance officers. The split 95:5 of on-street compliance costs private hire:taxi, changed from 80:20, was explained as reflecting the reason why the 250 compliance officers had been required, which was because of the increase in the private hire workload and changes to the way in which the private hire system worked, rather than because of any changes to the black cab trade. Ms Chapman also explained the change in step (iii) from an equal three-way split: on average an on-street inspection took 20 minutes, and she set out 2018 data and calculations which supported that, after the event. 20% or 4 minutes could properly be allocated as activity related to the operator. The growth of "app" based private hire operators had increased the need for officers to travel across London or even outside to check the operator's vehicles and drivers, waiting on roads or in residential areas to be allocated a booking. There was also an internal TfL document of September 2017 which helped apportion the operator fees across the tiers, not a point at issue in this ground of challenge.

- While I understand, as I have said, why the Claimant's concerns over cross-subsidy by operators to other licensees were aroused, the question for this Court is whether the Claimant has shown that the basis upon which the licence fees are charged to operators, now in the amended Regulations, involves their fees subsidising the fees charged to other licensees within the taxi and private hire system. This turns on the evidence produced by Ms Chapman. In my judgment, the Claimant has produced no counter-evidence and very little evidence-based argument to show that her evidence is wrong and that there is in fact such a subsidy.

- Ms Chapman's evidence explains a methodology for apportioning costs. She provides some evidence as to the data used. She explains why, though they varied over time, the various ratios were adopted. The Claimant has not set up any counter-analysis of its own to show that there is in fact a cross-subsidy. Nor has specific and clear issue been taken with any step in the methodology, or with the data used. The ratios have been criticised but not in any way which persuades me that there is a cross-subsidy embedded in the apportionment. Ms Chapman also produced the emails to which I have referred going back to 2016, as well as the later internal emails arising during the course of discussions about the apportionment exercise, but these rather emphasise the aim of producing "a robust and proportionate methodology" for calculating the fees for each of licence stream. The evolution of the figures is clear.

- Mr Matthias points to the small percentage of all licence holders made up by operators. But this is no indication of subsidy at all. Their applications are inevitably more time-consuming than others to consider. Ms Chapman has explained why Mr Wright's allied point, that inspections at operators' premises are low in number compared to on-street inspections, ignores the role which the operator plays in on-street inspections, including, with the new officers, the benefit of reassurance patrols, and other patrols outside premises from which they operate, notably at night-time venues, where they enforce rules, to the benefit of operators, against unlicensed vehicles and drivers. Thus, these costs need to be reflected in the fee payable upon grant. Mr Wright may be correct that most licensed operators are very compliant, but compliance and enforcement against unlicensed operators is important for them too.

- I cannot see from the outcome either that operators are bearing all the costs. They are bearing 20 percent of private on-street enforcement costs. Mr Wright has not persuaded me that they should pay no such costs, nor that any other lesser percentage is the maximum payable before a cross-subsidy comes into operation.

- I appreciate that Mr Wright does not agree with TfL, but he produced nothing of substance to show a cross-subsidy had been created, beyond his expressions of disagreement. It is unlikely that any methodology, data, or judgment on such an apportionment would meet either approval amongst all licence streams or be beyond criticism, let alone one which could produce a perfect fit between fees and costs.

- What TfL have done is to produce a reasonable method, with some evidence, to which reasoned judgment has been applied. It has not been shown to be wrong on its face, and on the analysis which I have had, I am not persuaded that there is any unlawful subsidy. If the Mayor did intend to convey that operators would pay a fee for costs which properly belonged to taxis or drivers or vehicles, the TfL officers have not in fact carried through any such intention. It would have been unlawful, had they done so.

- Mr Matthias described TfL as simply paying "lip service" to the principle of no cross-subsidy. The "lip service" allegation, and like language peppered Mr Matthias' submissions. He relied on the Mayor's comment in the 2016 Press Release, and the 2016 emails to which I have referred. The changes were "a political decision" to increase the number of enforcement officers; (which I would accept) "and to saddle private hire operators with the lion's share of the increased costs". He accused TfL officers of "attempting to construct a kind of ex post facto rationalisation for the imposition of the 'lion's share' of the cost" of the extra staff on operators. This is close to accusing officers of bad faith or untruthful evidence, on a wholly inadequate basis, especially with the extensive disclosure of internal materials relating to the process of the decision-making.

- That accusation, that TfL have in fact deliberately achieved a cross-subsidy while denying it in its words, is not justified. There is nothing in the September 2017 report or debate or outcome to support it. On the contrary, they refute it. There was an obvious need to alter the operator fee structure which would lead to increased fees for some, of itself. The proportion of on-street costs allocated to operators is 20 percent. The evidence of Ms Chapman justifies that; Mr Wright may disagree but her analysis was not effectively disproved at all. The taxi driver and vehicle fees go up 10 percent, the private hire driver and vehicles go up by 40 and 25 percent. The operator licence fee increase is greater, essentially because of the greater level of tiering as opposed to a flat fee for operators with more than two vehicles, as the table of regulated changes makes clear. An operator of over 10,000 vehicles used to pay £2826, and now pays £2.9m. The "lip service" allegation in fact acknowledges that the September 2017 report contains no suggestion that the apportionments are intended to load costs disproportionately on to operators, but rather to make them reflect the costs to TfL of regulating operators.

- Mr Matthias quoted from what Ms Chapman said in the Press Release, introducing the consultation paper, which I have set out earlier, that "it was only fair" that operators' fee "accurately reflect the costs of enforcement and regulating the trade". The "trade" he said meant "the taxi and private hire trade" as a whole, hence the very large increases for operators and comparatively small increases for private drivers and vehicles, and for taxis. He also quoted from other parts of the Press Release: operator fee income would "be used to contribute to funding" the extra 250 officers who would provide on-street reassurance to night-time travellers. This, he said, was irrelevant to operators who did not operate on the streets. I consider this to be making bricks without straw. His interpretation of what Ms Chapman said in the Press Release is not so clear, taken by itself, to warrant the serious allegation he makes, nor are Press Releases suitable for close interpretation. But when read with the consultation paper, the September 2017 report, its outcome and the analysis behind it, this contention is impossible.

- Some 2016 emails and the Mayor's comment in the Press Release of 2016, do afford some support for the existence of an intention in 2016 that operators should pay more than the costs properly attributable to them, though those are open to a different interpretation and are not themselves susceptible to close interpretation. However, they do not begin to show that any such intention was actually carried through in the light of the September 2017 report, its outcome and Ms Chapman's evidence. True, it is that none of the pre-consultation working was disclosed, though clearly there had been some, but ground 2 focused on the outcome, not any pre-consultation working. True it is that there were post-consultation iterations before the figures were finalised for a regulatory amendment. But I see nothing strange let alone sinister in that. Rather I see an intention to produce lawful fee structure in the desire expressed to put forward a methodology which "can be robustly justified if challenged by internal and external stakeholders". I found nothing to support Mr Matthias in the Mayor's role as TfL Chairman or Ms Shawcross' as Chair of the Finance Committee.

- This application is accordingly dismissed.

MR JUSTICE OUSELEY :

Legislative background

The non-statutory consultation process

"Transport for London (TfL) has today opened a consultation on proposals to change the fees private hire operators are charged for the costs of licensing, compliance and enforcement activity. This would ensure that operators pay a fee according to the resources required to regulate their operations.

The proposals would see an end to the current system where 'small' operators, with no more than two vehicles, pay £1,488 for a five year licence. 'Standard' operators, which have more than two vehicles, regardless of the size of their fleet, currently pay £2826.

The Capital's private hire industry has grown dramatically, from 65,000 licensed drivers in 2013/14, to more than 117,000. The number of vehicles has increased from 50,000 to 87,000 over the same period. With this growth, there has been a substantial increase in the costs of ensuring private hire operators fulfil their licensing obligations and in tackling illegal activity to keep passengers safe. It is estimated that over the next five years enforcement costs alone will reach £30 million from a previous estimate of £4m.

The total projected costs for licensing, enforcement and compliance for the taxi and private hire trades over the next five years is £209m.

The proposed new fee structure will replace the existing two 'tiers' with five; with charges ranges from around £2,000 for a five year licence for those with 10 vehicles or fewer, to £167,000 plus £68 per car for large operators with more than 1,000 vehicles. This would ensure the licence fee structure for private hire operators reflects the costs of compliance activity according to the scale of each operator.

Close to half of all operators have 10 vehicles or fewer, with just five percent of companies in charge of fleets of over 100 vehicles. TfL is also asking for views on whether there should be an option for operators in the top three tiers to pay their fees in annual instalments.

As set out in the Mayor's Taxi and Private Hire Action Plan, income from operator licensing fees will be used to contribute to funding the extra 250 Compliance Officers who are currently being recruited with a number of them now in post and the remainder being recruited by the summer. The team plays a pivotal role in keeping Londoners safe. They also provide reassurance to those travelling at night through a highly visible, uniformed presence in the West End, City and other areas across London.

Helen Chapman, General Manager of Taxi & Private Hire, said:

The operator fees system is no longer fit for purpose. It is only fair that licence fees for private hire operators accurately reflect the costs of enforcement and regulating the trade. The changes to fees would also enable us to fund additional compliance officers to help crackdown on illegal and dangerous activity."

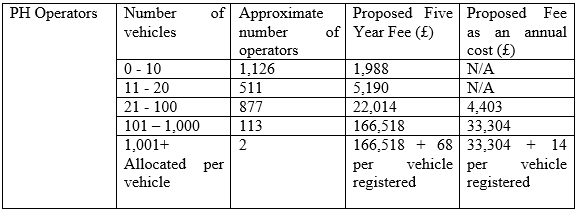

The press release said that operator fees, instead of the existing two bands, would be replaced by 5 tiers of 5 year licences which it tabulated:

"Owing to a number of developments within the private hire industry including advancements in new technology and an increase in the different ways people engage and share a taxi and private hire services, we have undertaken a review of the current policies and processes that govern the licensing of private hire drivers, vehicles and operators.

The TfL Board agreed to consider changes to the existing licence fee structure to better reflect the way in which costs are generated.

We now invite comments on our proposed changes to the fee structure. Where possible, consultees are asked to provide evidence or examples in support of their comments and suggestions."

"The total projected licence and compliance costs for the taxi and private hire trade over the next five years is £209m. This is apportioned between the fees received from the two trades based on the anticipated demand for resources to undertake the required compliance activities. This is forecast to be around 15 per cent of fees received from the taxi trade and 85 per cent from the private hire trade. Operator licensing administration costs of approximately £8m and TfL incurred operator enforcement costs are approximately £30m over a five year period.

To offset the increases in the scale of charges that larger operators will need to pay in the future, and to not unduly present a barrier to entry for smaller growing operators seeking to move up (or down) between the various fee tiers over a five year period, subject to feasibility, we will continue to consult on allowing operators in the largest three categories to pay their fees in annual instalments."

The "Purpose of the consultation" was described:

"The purpose of the consultation is to set out our proposals for changes to the London private hire operator's fees so they accurately reflect the costs to TfL of administering and enforcing a high quality service. We invite comments on the proposals.

Consultees are invited to comment on any aspect of the proposals or make other suggestions and, in particular, are invited to provide any evidence relevant to issues or proposals that are discussed."

"Do you agree with our proposals to change the existing structure to reflect the size of private hire operators? No.

Do you agree with the proposed tiers to be used to allocate fees? No

Do you agree that operators in the three largest tiers should be able to pay the grant of licence in annual instalments? No

Do you have any further comments?

The LPHCA opposes the Transport for London (TfL) 'Private Hire Operator Licence Fees' proposals and maintains the need for immediate suspension of the consultation process.

We believe the 'Private Hire Operator Licence Fees' proposals represent a disproportionate increase from the current fee structure. The grounds for the increase remains unsubstantiated and no justification has been presented for the effects upon the livelihoods of licence-holders. It is therefore further submitted that the current fee proposals are unreasonable.

We submit the overall consultation process, incorporating the 'Have your say on Private Hire Operator Licence Fees' survey, unnecessarily and improperly contravenes, amongst other criterion, Cabinet Office 'Consultation Principles 2016' guidance. Our complaints, regarding the consultation to date, include: .(8) TfL has disclosed limited justification, or basis, for the proposals.

We have separately presented the above complaints and opened a dialogue with senior TfL representatives on these matters. Supporting Freedom of Information Act 2000 requests have been sent, and whilst TfL has failed to comply with statutory deadlines, information continues to be sought for TfL's basis for these proposals.

In conclusion, the LPHCA strongly opposes the Licence Fee proposals contained in the consultation document and we believe TfL's conduct in undertaking this consultation process has been wholly unacceptable. The Association has been left with no other option but to answer "No" to each question and makes a formal complaint to TfL about the consultation process.

As London PHV operators have historically had very high compliance rates and very few category 7 failings, without the information we have sought from TfL Taxi and Private Hire, it is impossible to use the consultation process as the basis for giving a informed opinion about future licensing fees for licensed PHV Operators.

As Private Hire Licensing in London is determined in law in three separate classifications Operators, Drivers and Vehicles, we also wish to submit that Operator licensing fees must be utilised to manage PHV Operator licensing and must not be appropriated to the wider compliance of PHV Drivers and Vehicles or the London Taxi industry."

"This is not a sustainable position as it means that funding is required from other TfL budgets to maintain essential licensing activities which are in the interests of public safety.

We are proposing to make adjustments to the fees for private hire drivers and vehicles, and for taxi drivers and licensed taxis, in line with our annual process of reviewing licence fees.

For private hire operators, we are proposing a new licence fee structure that covers the costs to TfL of regulatory, licensing and enforcement activities associated with the regulation of operators, including pre and post licensing costs and take into account changes in the sector including those resulting from the development of new technology.

The proposals represent a substantial change to the current fee structure for operators and it is accepted that the size of the proposed increase in fees will have a significant adverse impact on some operators.

We undertook a public consultation to seek views on our proposals. The consultation took place from 20 April to 16 June 2017.

We received 1,442 responses to the online consultation, and an additional 15 written representations from the main private hire operators and other stakeholders.

The majority of those who responded to the online consultation opposed the proposal to change the structure of operator licensing fees although some made alternative suggestions for how the discrepancy between the current licence fee and actual regulatory costs associated with small and large operators could be addressed. Similarly, a majority did not support the proposed tiers of charges for operators, nor the ability for larger operators to pay by instalments.

Written responses from stakeholders, mostly private hire operators, showed that, while there was general support for the principle of changing the current fee structure, there were concerns about the impact on small and medium sized operators. Many from small/medium sized operators said that the fees as proposed were not affordable and/or would make their business unviable and others highlighted impact on drivers and on customers if fees were passed on. The largest operators have also opposed the proposals in particular the scale of increased fees.

We have taken careful account of the potential adverse impacts identified. The changes are proposed in order to recover the proportionate costs of regulating the taxi and private hire trade and for that reason are considered justified.

Taking into account these concerns we have modified the proposed fee structure. Two proposed new tiers have been added to mitigate the financial impact on, and better reflect the size of, operators.

In the consultation, we proposed a 'per-vehicle' charge for operators with more than 1,000 vehicles. This has been removed following responses to the consultation."

The recommendations were appended.

"The consultation on operator licence fees ran from 20 April to 16 June 2017. It proposed a change to the fee structure whereby the existing categories of 'small' and 'standard' operator for licence grant fees would be replaced by a new five-tier structure for both application and licence grant fees. This was designed to reflect the actual cost of licensing and compliance activities that we are able to recover.

The proposed new structure is set out at Appendix 2 along with a breakdown of operator cost forecasts and allocation across tiers. The forecasted gross expenditure to be recovered between financial years 2017/18 and 20121/22 is £209m, which includes deficits brought forward from previous financial years. The calculation is based anticipated demand for resources to undertake the required regulatory activities over the next five years.

16 per cent of the £209m will be recovered from fees received from the taxi trade and the remainder from fees received from the private hire trade. This split has been calculated following a detailed review of regulatory activity and the costs being apportioned to the different license activities. The methodology is set out in Appendix 2.

Private hire operator licensing administration costs are approximately 38m and operator enforcement costs are approximately £30m, over a five year period. The resulting net private hire operator expenditure relating to the licence period of £38m was allocated to 'Tiers' based on assumptions around staff time and other associated costs required for each tier.

All forecasts have been based on the assumptions included in the 2016 Business Plan and not a more up to date figure. This enabled TfL to establish a firm baseline upon which to generate proposals, put together consultation documents, hold consultation exercise, consider responses to the consultation and make recommendations. Using the forecast included in the 2016 Business Plan ensures that the financials and volumes used remained consistent throughout the process. These figures are set out in Appendix 2.

To mitigate the impact of the proposed increases in the size of fees that larger operators will need to pay in future and to not unduly crate a barrier to operators seeking to scale up their businesses over a five year period, we proposed in the consultation that operators in the larges three categories should be able to pay their fees in annual instalments.

We also proposed in the consultation that an element of the fee would comprise a flat per-vehicle fee for those with fleets over 1,000 vehicles."

"Increase fees for private hire drivers and vehicles instead of for operators

4.22 Our proposals already include an increase in licence fees for private hire drivers and vehicles to reflect the associated regulatory costs. If taken forward, these fees will still represent around two thirds of total licence fee income.

4.23 However, there are licensing and regulatory activities which are necessary for an operator but which are not in the case of drivers or vehicles. For example, an inspection of the proposed operating premises is required even before a licence is granted to ensure the operator and premises are suitable. This includes assessment of the booking system or platform to make sure it is compliant with private hire legislation. Further work to assess the proposed operating model may often be needed.

4.24 Once a licence is granted there are a range of activities necessary to ensure the operator remains compliant. These activities include regular compliance visits; inspection of booking records; inspection of driver and vehicle records and ensuring appropriate insurance is in place; contacting operators through on-street checks; handling of complaints regarding the operator or a driver or vehicle undertaking a booking for that operator.

There should be a cap on PHV driver numbers instead to minimise level of enforcement activity.

4.25 We do not have the statutory power to do this and it would be unlawful to try and achieve it through the licence fee regime."

"The Implementation of these proposals will have a financial impact on private hire services, in particular operators. However, it is appropriate and justified that operators, drivers and vehicle licensees pay appropriately for the proportionate costs of the licensing regime with them.

The proposed fees will not fully recover the licensing, compliance and enforcement costs incurred by TFL. This effectively means that other funding streams are subsidising the regulation of the licensed trades. For this financial year we are proposing structural changes to ensure that operator fees are related to the size of their business. We will proceed with any further proposals in future financial years to ensure full cost recovery across all licensees."

"The forecasted gross expenditure to be recovered between financial years 2017/18 and 2021/22 is £209m. This includes £204m expenditure forecasted to be incurred between the above financial years based on the financials included in the 2016 Business Plan and £5m of retained deficits brought forward from 2016/17.

These costs are then apportioned to the licence streams using the following methodologies:

For example, Operator costs for the five year licence period consist of the following:

The law on consultation

"In R v Brent London Borough Council, ex p Gunning, (1985) 84 LGR 168 Hodgson J quashed Brent's decision to close two schools on the ground that the manner of its prior consultation, particularly with the parents, had been unlawful. He said at p 189:

"Mr Sedley submits that these basic requirements are essential if the consultation process is to have a sensible content. First, that consultation must be at a time when proposals are still at a formative stage. Second, that the proposer must give sufficient reasons for any proposal to permit of intelligent consideration and response. Third, that adequate time must be given for consideration and response and, finally, fourth, that the product of consultation must be conscientiously taken into account in finalising any statutory proposals."

Clearly Hodgson J accepted Mr Sedley's submission. It is hard to see how any of his four suggested requirements could be rejected or indeed improved. The Court of Appeal expressly endorsed them, first in the Baker case, cited above (see pp 91 and 87), and then in R v North and East Devon Health Authority, ex parte Coughlan [2001] QB 213 at para 108. In the Coughlan case, which concerned the closure of a home for the disabled, the Court of Appeal, in a judgment delivered by Lord Woolf MR, elaborated at para 112:

"It has to be remembered that consultation is not litigation: the consulting authority is not required to publicise every submission it receives or (absent some statutory obligation) to disclose all its advice. Its obligation is to let those who have a potential interest in the subject matter know in clear terms what the proposal is and exactly why it is under positive consideration, telling them enough (which may be a good deal) to enable them to make an intelligent response. The obligation, although it may be quite onerous, goes no further than this."

Mr Matthias rightly did not contend that TfL was not entitled to choose for itself the scope of this non-statutory consultation. It is not open to legal attack on the basis that the scope of the non-statutory consultation should have been wider, save on those grounds which would have required a consultation exercise in the first place, perhaps irrationality apart. It was not alleged that the scope of this consultation was unlawfully narrow.

The consultation issue

"TfL consulted in April 2017 on the principle of amending the private hire operator licence fee structure. TfL was aware that the proposed changes to the fees for private hire operators were significant. TfL consulted in order to obtain views on the proposals for increasing the operator licence fees, in particular the proposals for revised tiers. The consultation was not inviting views on other licence streams e.g. taxi driver and vehicle licence fees and private hire driver and vehicle licence fees."

"Respondents were able to offer views on the prospective apportionment between trades and the proposed tiers for operator licence fees. As above, TfL was not consulting on any proposed revisions to the licence fees for the other licence streams."

Ground 2: cross-subsidy

" patrol London's streets and crack down on illegal activity and improve safety. The Mayor's move quadruples the size of a team which provides a highly visible, uniformed presence in the West End, City and other areas across London."

Later it said, and this language aroused suspicions:

"The new officers will be funded through changes to private hire operator licensing so that larger firms pay a greater share of the costs of enforcement."

Mr Matthias also referred to the description of the success of a recent enforcement operation, none of which referred to operators, at least not explicitly.

"i .Time and motion study this calculated, using defined vehicle based tier sizes, the total minutes spent inspecting each operator;

ii. Compliance costs apportionment the total compliance cost apportioned to private hire operators was apportioned to each tier based on the total minutes spent inspecting each operator (calculated in (i));

iii. Licensing and Policy costs apportionment the total licensing and policy costs apportioned to private hire operators was then apportioned to private hire operators was then apportioned again to each tier based on management judgment of the number of person days required to review, assure and process an application per tier;

iv. Combined cost the total compliance and licensing and policy costs were then combined to calculate total costs per tier;

v. Fee calculation the total costs was then divided by the number of operators per tier (after the impact of deferral) to calculate an overall recoverable fee; and

vi. Application and licence fee split the overall fee was then split be a percentage split was then 40% application fee and 60% licence fee."

"i. Apportion total compliance time spent on on-street enforcement/compliance activity versus operator centre inspections on an 85:15 ratio;

ii. Apportion the on-street related compliance costs to the private hire and taxi trade on a 95:5 ratio;

iii. Apportion the private hire on-street related compliance costs to the licence streams as follows: 50% vehicles, 30% drivers and 20% operators;

iv. Apportion the taxi on-street related compliance costs to the licence streams as follows: 60% vehicles, 40% drivers; and

Adopt the proposed methodology to apportion the private hire operator licensing costs to the operator tiers."

Overall conclusion