Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

England and Wales Family Court Decisions (other Judges)

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> England and Wales Family Court Decisions (other Judges) >> T v T (variation of a pension sharing order and underfunded schemes) [2021] EWFC B67 (10 November 2021)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWFC/OJ/2021/B67.html

Cite as: [2021] EWFC B67

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

Case No: OX13D00825

IN THE CENTRAL FAMILY COURT

Central Family Court

Date: 10th November 2021

HIS HONOUR JUDGE EDWARD HESS

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

B E T W E E N

Mr T Applicant

and

Mrs T Respondent

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Ms Ann Hussey QC appeared for the Applicant Husband (instructed by Goodwins Family Law Solicitors)

Mr Michael George appeared for the Respondent Wife (instructed by Russells, Solicitors)

(Handed down by email on 10th November 2021)

JUDGMENT

This judgment was delivered in private, but the judge has given leave for any part of this version of the judgment to be published,

His Honour Judge Edward Hess

1. This case concerns the financial dispute arising out of the divorce between Mr T and Mrs T. I shall refer to them in this judgment as ‘the husband’ and ‘the wife’ for ease of reference, though I am well aware that they have been separated since 2013 and divorced since 2017, and I apologise if the nomenclature seems odd to them.

BACKGROUND FACTS AND RELEVANT CHRONOLOGY

2. I shall begin this judgment by setting out (at a little length) some background facts and a relevant chronology to give the reader of this judgment an understanding a context for the issues I have to resolve.

The marriage and its breakdown

3. The husband is aged 53. He was initially working in a junior position with Company X and impressively raised himself over a long career to be the commercial director. He left Company X in 2018 and now works as group commercial director for Company Y, who are in the same field as Company X. He has had some health issues, including testicular cancer scares and eye problems, but they do not currently significantly interfere with his ability to work. He now cohabits with Ms A, who currently does not work for her own health reasons.

4. The wife is also aged 53. In younger days she was a champion Irish dancer of some note and she still does some dance teaching, but her main employment is as a hospital administrator. She has also had some health issues, including suffering from fibromyalgia and osteoarthritis, but again they do not currently significantly interfere with her ability to work.

5. The parties commenced their relationship in 1990, began cohabiting in 1992 and married in1995.

6. The marriage produced two children:-

(i) B was born in 1996 and is now aged 25. She is an independent adult.

(ii) C was born in 2001 and is now aged 20. She currently attends university and is in her second year.

7. A family home in Croydon was purchased in 2001 and the whole family lived there during the marriage.

8. The parties’ relationship sadly broke down and they separated in June 2013. The wife remained living in the family home with the children and the husband has lived separately ever since. In 2014 he purchased a home for himself in Sussex.

9. The husband commenced divorce proceedings on 28th June 2013. Decree Nisi was ordered on the 31st October 2013. In the conventional way, Decree Absolute awaited the outcome of the financial remedies proceedings.

The financial remedies proceedings: from Form A to judgment

10. The wife issued Form A on 1st April 2014. Both parties were legally represented throughout the proceedings. The application went through its conventional stages, including an FDR on 31st March 2015, but remained contested and found its way to a final hearing before DJ Thomas at the Family Court in Bromley on 13th August 2015 and 30th September 2015 (the gap between the two hearing days was apparently attributable to the happily unusual experience of the wife’s counsel going into labour on the first day of the hearing).

11. Judgment was delivered orally at the end of the court day on 30th September 2015. In very broad terms the parties’ capital position, including the redistribution effected by the court decision, was assessed by DJ Thomas as follows:-

(i) The judge assessed the family home in Croydon as having a gross value of £575,000 and a net equity (after deducting the Halifax mortgage of £197,000 and notional sale costs) of £363,000. This asset to be was transferred to the wife, subject to the mortgage, to enable her to house herself and the children.

(ii) There was another property in Sussex, purchased after the separation by the husband, and the judge assessed this as having a gross value of £650,000 and a net equity (after deducting the mortgage of £585,000, an early redemption penalty and notional sale costs) of £30,900. This asset was to remain in the husband’s ownership.

(iii) The husband had a Company X pension fund with a CE of £826,125 and an Aegon pension with a CE of £76,990. The wife had a Legal & General fund with a CE of £77,232. There would be a 40% pension sharing order in relation to the husband’s Company X pension in favour of the wife.

(iv) There was a Legal & General Endowment policy, thought by the judge to be worth c £31,000 (though it subsequently realised a higher amount).

(v) The husband had just purchased a new motor car for £50,000, which was included in the judge’s analysis.

(vi) Overall, after redistribution, the position (as it would have appeared on 30th September 2015, although the judgment does not actually include an assets schedule, so this analysis contains some speculative infilling) would have been broadly as follows:-

|

100% of the family home in Croydon |

363,000 |

|

Savings in own name |

30,000 |

|

Chattels in sole name |

31,500 |

|

Legal & General endowment policy |

31,000 |

|

Pensions in sole name |

77,232 |

|

40% x the husband’s Company X pension |

330,450 |

|

TOTAL |

863,182 |

Husband

|

100% of own home in Sussex |

30,900 |

|

Savings in own name |

30,000 |

|

Chattels in sole name |

54,000 |

|

Pensions in sole name before pension sharing order |

903,115 |

|

40% x Company X pension sharing order |

-330,450 |

|

TOTAL |

687,565 |

(vii) The judge’s justification for the 40% pension sharing order was fairly broad brush, was not fixed by any reference to any precise mathematical calculation nor to any of the income production data which had appeared in the PODE report from Mr Clive Weir dated 22nd June 2015, which the judge had in his possession, but to which he makes no specific reference in his judgment. He explained his thinking in paragraph 36 of the transcript of judgment as follows:-

“I have taken the view that the amount of the share should be, and I am going to

do this in regards to the Company X pension, that 60 percent of that should be retained by Mr. T and 40 percent of his Company X pension goes to Mrs.T. This has the effect, and the exact figures I do not think I need to go into, of Mr. T getting slightly less than 50 percent of all the assets and Mrs. T getting slightly more. In that regard, as I say, I have taken into account all the circumstances and I have taken into account the position of both parties, the contribution of both parties and the ongoing contribution that Mrs. T will make to the children. That is going to inhibit her housing ability and really inhibit her earning capacity in the future. That is the reason that I think it is appropriate to depart from equality. But it is not a dramatic departure from equality. It is merely looking at the fact that effectively all the value in the house goes to Mrs. T”.

In essence this seems to have been a broadly based decision involving an element of offsetting (the pension value against the family home value), departing from equality to some extent in the wife’s favour for the reasons described, i.e. mainly the wife’s housing needs on behalf of herself and the children and the parties very diverse incomes (he assessed the wife’s income at c £19,000 per annum net and the husband’s income at c £120,000 per annum net). The capital/pensions element of the order was not appealed and nobody has subsequently suggested, before me or otherwise, that it was wrong.

12. There was also to be a substantive global periodical payments order which (subject to the death of either party, the remarriage by the wife or further order of the court) was to commit the husband to making maintenance payments to the wife until 2030. This has been the subject of subsequent appeal and variation, in particular the fact that a good deal of the husband’s income came in performance related bonuses has caused a difficulty, but I do not consider it necessary in the context of the present dispute to go into the details of this aspect of the case.

The financial remedies proceedings: from judgment to order

13. Because of a series of ongoing arguments (including about chattels and about detailed drafting points) it took an unusually long time for the judgment to be converted into a perfected order. It was not until 3rd May 2016, more than seven months later, that the order was perfected and sealed by DJ Thomas (after a contested hearing). For all this time (rightly or wrongly) both parties took the view that it was not appropriate to obtain Decree Absolute - certainly neither party applied for Decree Absolute.

14. Even after that point, there were problems over drafting the pension sharing annex. In a letter dated 2nd August 2016, the original version was commented upon by the pension administrators (at that stage Company D), including the following remark:-

“Paragraph F of the Annex should have the "external transfer” box marked as the Trustee of the scheme does not permit internal transfers. Failure to do so will not invalidate the Annex”.

It appears that in October 2016 a further unsealed version of the annex was presented to Company D, this version obediently ticking the external transfer box in paragraph F. At some stage, possibly in early 2017 (the date is not clear in the papers), the court sealed this version of the annex and at some stage after that, in the course of 2017, the sealed version came into the possession of Company D.

15. At some point after that Company D were replaced as pension administrators by Company E. For reasons I explain below the pension sharing annex has never been implemented.

The appeal

16. Alongside this activity in 2016, the husband sought permission to appeal against the final order (although not against the pension sharing order).

17. The appeal proceedings rumbled on until 11th November 2016, when the appeal was compromised by an order of HHJ Redgrave which varied certain aspects of the original order, but not the pension sharing order.

18. For all this time, again, both parties (rightly or wrongly) took the view that it was not appropriate to obtain Decree Absolute - certainly neither party applied for Decree Absolute. This was notwithstanding the order of HHJ Redgrave dated 21st July 2016, expressly permitting the husband to apply for Decree Absolute.

Developments in the Company X pension scheme and reactions to it

19. Matters might by now (early 2017) have drawn to a conclusion had there not been some developments within the Company X pension scheme which affected the parties and how they saw the fairness of the operation of the pension sharing order.

20. On 11th October 2016 a revaluation of the husband’s Company X pension produced a CE of £1,795,362 (substantially up from the figure used at court in September 2015, i.e. £826,125). The husband began to perceive that the wife would be receiving more than she should have done. By 8th June 2017 this was revalued at £1,652,012, a slight fall but still substantially higher than the figure used in September 2015.

21. A further complication occurred on 5th December 2016 when Company X announced a policy of substantially reducing CEs for the purposes of external transfers on the basis that the scheme was underfunded. On the June 2017 valuation the CE for an external transfer was reduced from £1,652,012 to £722,138 so that a pension sharing order implemented at this moment by external transfer would have produced a pension credit of 40% x £722,138 = £288,855. The wife began to perceive that she would be receiving less than she should have done.

22. By early to mid 2017 both the husband and the wife were aware of these developments and both actively considered what they should do about them.

23. The wife was plainly worried about their implications, believing that she would be losing substantial amounts by receiving an external transfer, which she believed was her only choice. The fact that she believed this was her only choice stemmed from the information presented to her by Company D in August 2016, but this was presented at a time when the Company X pension fund was not paying reduced CEs and was thus correct at the time it was given and only became incorrect on 5th December 2016. She took legal advice from Solicitors and Counsel. It appears from the documents that I have seen that neither her Solicitors nor her Counsel (nor indeed Company D) advised the wife of the existence of a remedy which would for all practical purposes have solved her problem, the selection of an internal transfer for the pension sharing order (I set out the statutory basis of this remedy in my section on the law below). There is no reason why the wife herself should have known about this solution to her problems, but it is disappointing that her lawyers did not know of its existence and arguably also troubling that the pension administrators did not alert her to this issue (a theme I shall discuss in more general terms below in the context of some recommendations made in the Pensions Advisory Group (PAG) report).

24. The wife’s legal team, in the erroneous belief that she was obliged to take an external transfer under the pension sharing order, decided to issue an application on 15th July 2017 seeking the following remedy:-

“The Applicant seeks a Declaration of the Court that the 40% share of the Company X Pension Fund in the Applicant's favour (and 60% in the Respondent's favour). also applies to the uplift in the value of the Company X Pension Fund policy. which Mr T Mrs T of on 20 January 2017. and specifically that the CEV had increased from £826,125 to £1,795,462”.

25. It is now accepted on behalf of the wife (expressly by Mr George) that this application was wholly misconceived and that the court would not and could not make such a declaration, but, at the time it was made, it was made (albeit with an erroneous understanding of the law) with serious intent and, as interpreted by the husband, then acting in person, it appeared that he would be substantially disadvantaged by the sought after declaration. Just as the wife and her legal advisers were not aware of the existence of the possibility of an internal transfer, so the husband was apparently unaware. He told me in his oral evidence that he did not become aware of this possibility until the hearing before me on 8th September 2021. Apparently neither his direct access Counsel (instructed on 18th April 2018) nor his full legal team of Solicitor and Counsel (whom he instructed from November 2018 onwards) knew about it or, if they did, they did not tell the husband about it.

26. The wife’s application was followed up (on 21st September 2017) with an application by the wife for Decree Absolute to be pronounced.

27. On 5th September 2017 the husband (acting in person) applied for a stay on the pronouncement of Decree Absolute. On 29th September 2017 DJ Thomas temporarily stayed any application for the pronouncement of Decree Absolute.

28. On 21st November 2017 the husband (acting in person) applied for a variation of the pension sharing order. This application had the legal effect of preventing the pension sharing order taking effect until the variation application had been determined: see Matrimonial Causes Act 1973, section 31(4A)(b). The absence of a Decree Absolute had prevented the pension sharing order taking effect until this point and from this point on the undetermined variation application had the same consequence - the net result is that the pension sharing order has never taken effect.

29. On 22nd December 2017 DJ Thomas gave permission for the pronouncement of Decree Absolute and this happened the same day. (I pause to note that if the husband had died at any time between 22nd December 2017 and today there would have been no widow’s benefits under the husband’s pension scheme and no effective pension sharing order and the wife could have lost out substantially, but happily the husband is still alive and this problem has not arisen, but, as far as I can see, nobody raised this point on 22nd December 2017 nor thought about until recently).

Onwards pursuit of the application to vary the pension sharing order

30. It has been a curious feature of this case that the wife’s misconceived application of 15th July 2017 for a “declaration” has never formally been dismissed or withdrawn, but as time has gone on the clear focus of the litigating lawyers has certainly been on the husband’s variation application.

31. I also note in passing that DJ Thomas dispensed with an FDR in this case as early as April 2018. It may be that his knowledge of these combatants informed this decision, but it is difficult to see why there should not have been an FDR in this case, which might have suggested a compromise before the costs massively and horrendously escalated.

32. Another startling feature of this litigation, looking backwards, is the fact that on 13th April 2018 the Company X pension trustees announced a reversal of their policy of substantially reducing CEs for the purposes of external transfers. It appears that the husband was aware of this important fact from an early stage, but did not inform the wife about it. She was unaware about this development until 24th March 2021, some three years later. In the meantime there had been court hearings on 18th April 2018, 23rd November 2018, (possibly) 5th September 2019 and 8th October 2020 and the husband was legally represented by the same Solicitor and Counsel between November 2018 and March 2021 and yet this very important fact had not been disclosed.

33. The discovery of this development in March 2021 lead the wife’s Counsel to put in her note for the hearing on 18th May 2021 before HHJ Gibbons, an invitation to the court:-

“to: (a) Forthwith implement the pension sharing orders in the Wife’s favour as to 40% of the Husband’s Company X pension fund on current values; (b) Record the dismissal of H’s application for variation of periodical payments; and (c) Order for costs in W’s favour.”

34. At the hearing on 18th May 2021, the reaction of HHJ Gibbons to these latest developments, noting a lack of clarity in the husband’s case, included an order that the husband should “serve and file a statement of case within 21 days”. This was done on 2nd July 2021 and the husband’s case was stated to be as follows:-

“DJ Thomas clearly offset the pension. He analysed outcome in terms of capital value

of the pension. His intention was to achieve a result which gave W £330,450 in capital

terms. That outcome can be achieved by varying the PSO to provide for such percentage as equates to £330,450 plus, it is accepted, an uplift for inflation. It is a matter for the court's discretion as to which of the various indices is used to calibrate the uplift.”

On the first day of the final hearing before me (i.e. on 8th November 2021) this was further clarified by Ms Hussey QC (the husband’s Counsel before me) as meaning that the pension sharing order should be varied downwards from 40% to 17%. She has held to this position in her closing submissions.

35. Another troubling feature of this litigation has been the pursuit, largely by the husband’s legal team, but for a long time by the wife’s legal team as well, of a PODE report which sought (amongst other things): “a report of the effect of the Company X pension deficit (if any) on both parties’ pension share and how in light of any deficit the 60:40 split ordered can be preserved”. This question, which was approved by the court on 22nd November 2018, seems to me to have been misconceived ab initio as a question to ask of a PODE. In the light of the fact that by the time it was drafted Company X were already paying out full CEs and the underfunding was largely irrelevant, it is an even more extraordinary question - though of course this fact was known only to the husband’s legal team until March 2021. To add to the tragic chronology of this case, it took from November 2018 to June 2021 to get the questions to a PODE - Ms Caroline Bayliss of Excalibur Actuaries - who quickly (and in my view entirely correctly) pointed out some of the flaws in the letter of instruction and concluded that there is “little to justify a pension sharing report…I will therefore decline the instruction”. Even after this, the husband’s legal team continued to push the point until I discharged the direction for the involvement of a PODE on 8th September 2021.

36. On 8th September 2021 I made a direction setting out the matters upon which I sought clarification from the pension administrators. To their credit Company E moved quickly to provide this information and, in a letter dated 15th September 2021, they clarified the following matters:-

(i) Whilst the Company X pension had paid out reduced CEs between 5th December 2016 and 13th April 2018, this had not been the case since then and there is no reason to suppose that this position will change prior to December 2021. In any period of reduced CEs internal transfers would have been offered as “the law states that an ex-spouse cannot be forced to transfer their pension credit out of the fund on a reduced basis”.

(ii) The most recent CE for the husband’s pension fund was (as at 2nd August 2021) £2,471,833.

(iii) Because of some rule changes made in March 2016, the “variation in the CE quoted… since 31st March 2016 is… almost entirely the result of changes in actuarial assumptions over time, with the primary driver of these changes being changes in underlying financial conditions. In particular, the discount rate used to calculate the present value of the…benefits is linked to market gilt yields”.

37. On 16th September 2021, bolstered by this clarification, the wife again made an open offer to the effect that the husband’s variation application be dismissed with costs. In his case summary Mr George (the wife’s Counsel before me) has largely advanced that position, but he has also put forward an alternative position to the effect that the pension sharing order be varied to 50%, but without a costs order - I think it would be fair to say that the alternative position has been advanced with some diffidence and most of his submissions concentrated on the main proposition, i.e. that the husband’s variation application should simply be dismissed with costs. None of these developments appear to have brought on any change of thinking within the husband’s legal team, or at least in their open position.

38. I have accordingly dealt with the application over three days on 8th, 9th and 10th November 2021. Evidence was completed on the first day and submissions by lunchtime on the second day. I am handing down this written judgment on the afternoon of the third day.

39. I have been told that the respective legal costs incurred on this application are £130,487 for the wife and £175,024 for the husband. That costs should have been incurred at this level on this application is a tragedy for this family and also a shaming indictment for the legal system, even more so as much of these costs were incurred by legal teams who appear to have had limited understanding of the issues with which they were dealing. In making this latter comment I should like to clarify that it does not apply to the wife’s legal team in the months since at least May 2021 and Mr George is specifically exempted from this criticism.

APPLICABLE LAW

40. It is necessary for me to set out some law relevant to this variation application. I shall divide this part of my judgment into two parts. The first relates to the procedures involved in making and implementing pension sharing orders. The second relates to the proper legal tests to be applied in dealing with an application for a variation of a pension sharing order under Matrimonial Causes Act 1973, section 31.

Procedures involved in making and implementing pension sharing orders

41. This case involves an extreme example of what is often called ‘moving target syndrome’. To understand what that is, it is necessary to know that in H v H [2010] 2 FLR 173 Baron J said:-

“although the court may calculate the percentage by taking the precise capital sum that seems appropriate and undertaking a calculation to determine the relevant percentage, the result contained in the order must be specified only in percentage terms and not 'such sum as will give such percentage'. The latter seems to me to be a method of calculation as opposed to an order”.

This dicta is binding and any pension sharing annex should go no further than stating the percentage of the member spouse’s pension rights which are to be transferred to the non-member spouse as a pension credit. It should not include any formula for the production of a certain level of income or for a particular monetary sum to be transferred.

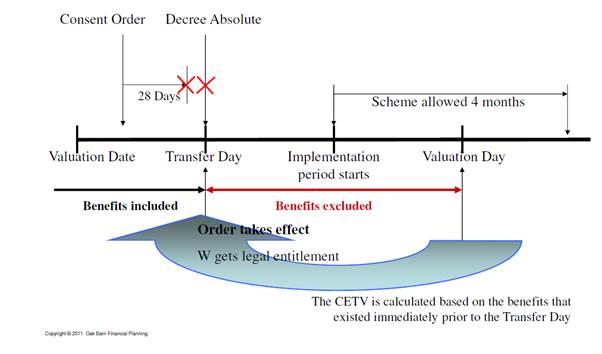

42. A related aspect is the implementation sequence of a pension sharing order - in particular the sequence of dates from valuation date (the date the pension was valued for the original court final hearing) to transfer day (the day the order takes effect) to the start of the implementation period of four months to the valuation day (within the implementation period). This is helpfully illustrated in the figure below [1]:-

43. It is a consequence of the above that the value of the pension credit actually transferred as a result of a pension sharing order will usually not be the precise amount contemplated by the judge deciding the level of the percentage to be included in the pension sharing order and annex. Hence the expression ‘moving target syndrome’, which is described in Hay, Hess, Lockett and Taylor on Pensions on Divorce: A Practitioner’s Handbook (3rd edition at p.124) [2] as follows:-

“Once a pension sharing order is made, its implementation will in due course take place by reference to the percentage identified in the order. The percentage will not, however, be applied against the CE valuation figure which the court will have had before it on the day the order was made. Instead it will be applied to a fresh CE valuation figure of the shareable rights. This fresh valuation will be made by the pension provider as at ‘the valuation day’ [3]. The valuation day will ordinarily be some months after the court hearing and will be a date selected by the pension provider within a four month implementation period [4]. This leads to the difficulty which has been identified as “Moving Target Syndrome”. The valuation of the pension against which the pension sharing order is to be enforced may be quite different at the time of implementation from the valuation identified by the parties and the judge at trial. Commensurately, the level of the pension credit may also be quite different. Often this will not matter very much as the use of a percentage figure in the order will ensure that both parties will share proportionately in any increase or decrease in the value. Especially if the percentage of the pension sharing order to be executed is not very far away from 50% and the movements in value are relatively modest market fluctuations then little injustice will be done by the moving target, a fact observed by Baron J in H v H (Financial Relief: Pensions) [2010] 2 FLR 173 on the facts of that case. There may, however, be cases where significant injustice might be done by a moving target. It may be that some event, such as a significant drawdown from the fund [5], or a pay rise or fall for a member spouse holding a defined benefit scheme, between the date of the valuation and the date of the court hearing, which undermines the reliability of the CE used at court. The problem is the same for events which occur between the date of a hearing and the date an order is approved if, for example, the judge reserves judgment for a lengthy period [6]. The same applies in the period between the order being made and its taking effect. In some cases changes occurring between the date of the order taking effect and its implementation can also cause a similar difficulty; but it should be remembered that the rights which are valued are those which the member spouse has at the date the order ‘takes effect’ [7], also known as “transfer day” [8], so changes occurring at this point are less likely to make a significant difference. There are cases, however, where there might be significant differences. For example, there might be a significant change in market conditions or valuation methodology [9] in the course of the process of making and implementing a pension sharing order”.

44. I now turn to the procedures involved when a pension fund against which a pension sharing order is to be made, or has been made, declares itself to be underfunded. A pension is underfunded if it has insufficient funds to meet in full its obligation to all members of the scheme [10]. If the scheme is underfunded the pension trustees must decide if they wish to pay out only reduced CEs on external transfers from the fund - they may accordingly announce a reduction proportionate to the level of underfunding in the scheme [11]. The trustees of the scheme are not obliged to reduce CEs where the scheme is underfunded - they will wish to consider issues such as the level of underfunding, the strength of employer’s covenants and any recovery plans that may be in place to decide if such a step is necessary. If they are offering only reduced CEs on external transfers, however, this will have implications for what they must offer a non-member spouse in relation to the implementation of a pension sharing order. In contrast to most other situations, the pension provider cannot insist on an external transfer if the pension credit offered is based on a reduced CE. The pension provider must first offer the non-member spouse an internal transfer using the full value of the member spouse’s CE (i.e. without applying any reduction of the member spouse’s CE attributable to the underfunding) [12]. In many cases this will be the solution preferred by the non-member spouse; but if, having received this offer, the non-member spouse would prefer an external transfer then, provided a full explanation is given by the pension provider as to the reasons for the underfunding and of the likely timescale for the elimination of the underfunding, the pension provider may offer an external transfer on the basis that the member spouse’s CE used in the calculation will be reduced proportionately with the extent of the underfunding [13]. In such circumstances the percentage pension share will be implemented against a reduced CE.

Legal tests to be applied in dealing with an application for a variation of a pension sharing order under Matrimonial Causes Act 1973, section 31.

45. It is undoubtedly the case that a pension sharing order can (in limited circumstances) be varied by the court under Matrimonial Causes Act 1973, section 31(2)(g). The limited circumstances are, in particular, that the application to vary must have been made before the pension sharing order took effect and before Decree Absolute has been pronounced: see Matrimonial Causes Act 1973, section 31(4A)(a).

46. Duckworth on Matrimonial Property and Finance has suggested that this provision is not really targeted at cases involving other than those involving trivial tinkering with the wording of a pension sharing annex:-

“For reasons which are obscure, Parliament thought it necessary to confer the right to

apply for variation of a pension sharing order before decree absolute. Since a pension

sharing order made on decree nisi cannot, in any case, take effect until the decree has

been made absolute, the intention appears to be to allow the parties to come back to

court to tinker with the wording of the order (perhaps, as a result of representations

made by the pension managers). But this can equally well be achieved under the slip

rule. It is difficult to see these provisions being much used in practice.

47. In similar vein, Hay, Hess, Lockett and Taylor on Pensions on Divorce: A Practitioner’s Handbook (3rd edition at p.62) has suggested that “Appropriate applications under this section will be very rare beasts indeed”. Indeed, as far as I and Counsel in the present case are aware, there are no reported cases on such an application and I cannot personally recall coming across one before. The reason for this is perhaps obvious - the likelihood of circumstances arising between a final order being made and the pension sharing order taking effect (normally a period of no more than 28 days) to justify a substantive variation in the order must be very small.

48. Nonetheless, the power exists and the husband in this case invites the court to use it, so it is necessary to consider what sort of legal test should apply to such an application where it is made in relation to something not just in the nature of a tinkering with the wording of an order.

49. Mr George has addressed me very fully and very helpfully on this topic and I think there is a great deal of force in his submissions.

50. The starting point is and should be Matrimonial Causes Act 1973, section 31(7), which reads:-

“In exercising the powers conferred by this section the court shall have regard to all the circumstances of the case, first consideration being given to the welfare while a minor of any child of the family who has not attained the age of eighteen, and the circumstances of the case shall include any change in any of the matters to which the court was required to have regard when making the order to which the application relates”.

51. But that is only the starting point and I think Mr George is correct to suggest that the court will be assisted by placing a pension sharing order variation alongside other instances where variation of capital orders is involved.

52. This thought leads me rapidly to the decision of Bodey J, sitting in the Court of Appeal, in Westbury v Sampson [2002] 1 FLR 166. This case involved a consideration of the circumstances when a lump sum by instalments can be varied by the court under Matrimonial Causes Act 1973, section 31. He said (my emphasis included):-

“Nevertheless, given the constant emphasis in the authorities generally on the need to uphold the finality of orders intended to be final, including orders as to capital, it seems to me that very similar considerations ought in practice to be applied under s 31 as those laid down in Barder v Caluori [1988] AC 20, sub nom Barder v Barder (Caluori Intervening) [1987] 2 FLR 480, at any rate as regards varying the overall quantum of a lump sum order by instalments (as distinct from re-timing or 're-calibrating' the instalments). The re-opening under s 31 of the overall quantum of lump sum orders by instalments, especially when made as part of a package intended to be final…should only be countenanced when the anticipated circumstances have changed very significantly, and/or for cogent reasons rendering it quite unjust or impracticable to hold the payer to the overall quantum of the order originally made. This formulation gives a little more latitude as regards s 31 of the Matrimonial Causes Act 1973 than do the Barder conditions for the grant of leave to appeal out of time; but that must I think follow from the statutory requirement under s 31(7) that the court is to consider 'all the circumstances'.”

53. This decision received obiter approval from the Supreme Court per Lord Wilson in Birch v Birch [2017] UKSC 53:-

“It is worthwhile to note that an order for payment of a lump sum is occasionally variable even if, as is likely, the variation will directly prejudice the interests of the payee. Thus section 31(2)(d) of the Act expressly empowers the court to vary an order for payment of a lump sum by instalments. In the words of Bodey J (with whom Schiemann and Sedley LJJ agreed) in Westbury v Sampson [2001] EWCA Civ 407, [2002] 1 FLR 166, at para 18, the subsection "not only empowers the court to re-timetable / adjust the amounts of individual instalments, but also to vary, suspend or discharge the principal sum itself, provided always that this latter power is used particularly sparingly, given the importance of finality in matters of capital provision"”

54. The Westbury v Sampson; Birch v Birch approach leaves variation of the overall quantum as a viable option in only a very few cases; but in his very recent decision of BT v CU [2021] EWFC 87 Mostyn J has doubted the correctness of even the modest liberality in Bodey J’s judgment, suggesting that the furthest a court should go under Matrimonial Causes Act 1973, section 31, is a “recalibration of the payment schedule” and that the original order “is not variable as to overall quantum” and that the only way of changing the overall quantum is to satisfy all the Barder conditions. If this analogy is applied to pension sharing order variation provisions, it is difficult to see how a variation to the pension sharing order percentage could be contemplated under Matrimonial Causes Act 1973, section 31. Nobody has argued, nobody could credibly argue, that the Barder conditions are met in the present case.

55. For the purposes of this judgment I propose to adopt the really quite strict Bodey J approach to capital variations (as opposed to the even stricter test suggested by Mostyn J) and record that in my view the husband can only succeed in his application to vary downwards the pension sharing order percentage if he can establish that “the anticipated circumstances have changed very significantly, and/or for cogent reasons rendering it quite unjust or impracticable to hold the payer to the overall quantum of the order originally made”.

ANALYSIS OF THE FACTS OF THIS CASE

AGAINST THESE LEGAL PRINCIPLES

56. Having noted all these matters, I now turn to my observations on how I should analyse the facts of the case against these criteria and what orders I should now make on the variation application.

57. I start by saying something about the “ property and other financial resources which each of the parties to the marriage has or is likely to have in the foreseeable future ” and the income and earning capacity of the parties and the changes to both these things this since 2015/2016.

58. In fact I need say little about this because things have progressed since 2015/2016 in a way which was broadly predicted by DJ Thomas in his 2015 judgment. The wife has carried on similar work, earning perhaps a little more than she did then, but she is broadly in the same place. She lives in the same home, the value of which has no doubt moved in line with normal house price changes over the time. Likewise, the husband has carried on similar work, earning perhaps a little more than he did then, and although he has moved his employment from Company X to Company Y, he is broadly in the same position. He also lives in the same home as he did, the value of which has moved in line with normal house price changes over the time. He has acquired a new domestic partner and a second property, but his overall position is not very different. The simple fact is that nothing very remarkable has happened since 2015/2016.

59. In relation to the “financial needs, obligations and responsibilities which each of the parties to the marriage has or is likely to have in the foreseeable future ” and the changes to these since 2015/2016, again, nothing is very different from what it was when assessed by DJ Thomas in 2015.

60. The case must, therefore, stand or fall on the issue of the change in the CE of the husband’s pension from the figure used by DJ Thomas at the hearing in 2015 (£826,125) and the most up to date figure (£2,471,833 - though this will no doubt change again when a revaluation is carried out during the implementation period which will, I hope, start soon).

61. To my mind there are three powerful reasons why this change in CE does not justify any variation in the percentage figure to be included in the pension sharing annex, gets nowhere near passing the Bodey J test to which I have referred above and would even fail a much lower test. They are the following:-

(i) The approach taken by Ms Hussey QC on behalf of the husband seems to me to involve a fundamental misunderstanding of what the CE of a defined benefit pension fund represents. The CE of a defined benefit pension fund is an actuarially calculated figure which seeks to establish what sum of money would be needed to invest to produce the income benefits which the fund is obliged to meet for a set period, i.e. the remainder of the recipient’s actuarially predicted life span. As market conditions change and gilt yields change (as they appear to have done between 2015 and 2021 on the evidence I have from LCP) more money will need to be invested to produce the same income benefits. The income benefits rise with inflation, but the money needed to produce that income stream for a prolonged period may rise by substantially more than inflation, as it has done in this instance. By suggesting that the wife should have her entitlements fixed now at the cash sum contemplated in 2015, even if the cash sum is given some inflationary growth, the husband is to my mind ignoring the fact that that cash sum will, as a result of the very changes in market conditions and gilt yields which have driven the increased CE, purchase commensurately lower income benefits than they would have done had the pension credit been transferred in 2016. To my mind a variation of the nature sought by the husband on the argued basis from 40% to 17% would be very unfair to the wife for similar reasons as those firmly, and in my view correctly, set out by Baron J in H v H [2010] 2 FLR 173 .

(ii) The approach taken by Ms Hussey QC on behalf of the husband seems to me to ignore the fact that, in so far as having a higher CE is a windfall benefit (and, for the reasons explained above, this can be illusory if one views a pension as an income producing asset) the husband has had an even greater windfall in that his residual 60% of the fund has gone up in value by even more (1.5 times) than the wife’s 40% portion of the fund. If we remind ourselves of the broad approach of DJ Thomas to the division of assets, which was to include the CEs in the asset schedule and step back to see what justifications exist for a departure from overall equality, whilst the wife’s overall asset figure is undoubtedly higher as a result in the growth of the CE, the husband’s overall asset figure is even more increased. Following the logic of DJ Thomas takes us down a road to the conclusion that no injustice is done to the husband to hold him to the 40% figure.

(iii) The reasons that the pension sharing order has not taken effect since it was first made in the judgment of DJ Thomas on 30th September 2015 are simply these. First, there was no Decree Absolute until 22nd December 2017. The husband could have applied for a Decree Absolute at any time after 30th September 2015, yet he did not, even though he was the petitioner on the divorce. Indeed, when the wife applied in September 2017 for a Decree Absolute to be made, he actively blocked it until December 2017. Secondly, on 21st November 2017 (just prior to Decree Absolute) the husband made a variation application and triggered the effect of Matrimonial Causes Act 1973, section 31(4A)(b). Overall, it seems to me that it is predominantly the husband’s actions which have prevented the pension sharing order taking effect for more than six years. By doing this he has left open the possibility of moving target syndrome more than in most cases and if he feels he has lost out by it then he is very substantially the author of his own misfortune.

62. In my view the husband’s application was hopeless from the outset. I accept that part of the original reasoning for making the variation application was to block or counter the wife’s misconceived application of 15th July 2017, but the proper response to that at the beginning would have been to resist it and point out the availability of the internal transfer rights which she had at that time and really dealt with her problem. The proper response after 13th April 2018 (when the Company X pension fund ceased paying out reduced CEs, a fact of which the husband was aware) would have been to inform the wife that there was no longer a problem and invite her to withdraw her application.

63. Accordingly, I propose to dismiss the husband’s application dated 21st November 2017 for a variation of the pension sharing order. In so far as it still exists (and I think it technically does) I propose also to dismiss the wife’s declaration application dated 15th July 2017.

COSTS

64. It is common ground between the parties that this application is one where FPR 2010 Rule 28.3 (5) to (8) apply. They reads as follows:-

“(5) Subject to paragraph (6), the general rule in financial remedy proceedings is that the court will not make an order requiring one party to pay the costs of another party.

(6) The court may make an order requiring one party to pay the costs of another party at any stage of the proceedings where it considers it appropriate to do so because of the conduct of a party in relation to the proceedings (whether before or during them).

(7) In deciding what order (if any) to make under paragraph (6), the court must have regard to –

(a) any failure by a party to comply with these rules, any order of the court or any practice direction which the court considers relevant;

(b) any open offer to settle made by a party;

(c) whether it was reasonable for a party to raise, pursue or contest a particular allegation or issue;

(d) the manner in which a party has pursued or responded to the application or a particular allegation or issue;

(e) any other aspect of a party's conduct in relation to proceedings which the court considers relevant; and

(f) the financial effect on the parties of any costs order.

(8) No offer to settle which is not an open offer to settle is admissible at any stage of the proceedings, except as provided by rule 9.17”.

65. Mr George on behalf of the wife has invited me to conclude that this is a case where I should make an inter partes costs order under FPR 2010 Rule 28.3(6).

66. In this context I remind myself of FPR 2010 PD 28A, paragraph 4.4:-

“In considering the conduct of the parties for the purposes of rule 28.3(6) and (7) (including any open offers to settle), the court will have regard to the obligation of the parties to help the court to further the overriding objective (see rules 1.1 and 1.3) and will take into account the nature, importance and complexity of the issues in the case. This may be of particular significance in applications for variation orders and interim variation orders or other cases where there is a risk of the costs becoming disproportionate to the amounts in dispute. The court will take a broad view of conduct for the purposes of this rule and will generally conclude that to refuse openly to negotiate reasonably and responsibly will amount to conduct in respect of which the court will consider making an order for costs.”

67. I also remind myself of the words of Mostyn J in OG v AG [2020] EWFC 52:-

“The revised para 4.4 of FPR PD28A is extremely important. It requires the parties to negotiate openly in a reasonable way… and so, the wife will herself suffer a penalty in costs for adopting such an unreasonable approach…It is important that I enunciate this principle loud and clear: if, once the financial landscape is clear, you do not openly negotiate reasonably, then you will likely suffer a penalty in costs. This applies whether the case is big or small, or whether it is being decided by reference to needs or sharing.”

68. In my view this is a clear case where the husband has taken an unreasonable view of the case from the outset and has pursued it to the bitter end. I have rejected his case and he has entirely lost. In my view he has failed to negotiate openly in a reasonable way and, by pursuing the variation application he has placed himself firmly in at least one of the categories identified in FPR 2010 Rule 28.3(7) ( whether it was reasonable for a party to raise, pursue or contest a particular allegation or issue).

69. I therefore propose to make a costs order against the husband. I propose to make a summary assessment of this costs order. Mr George has invited me to assess this figure at the full amount of costs incurred by the wife, i.e. £130,487. It is, I think, fair to make a deduction to reflect the fact that the original context of the husband’s application was against the wife’s misconceived application of 15th July 2017; but this provides an excuse only up to a point. In the circumstances, and taking a fairly broad view, but having firmly in my mind the open offers made by the wife in May 2021 and September 2021 and the husband’s open position as articulated in the July 2021 statement of case (which was really his position throughout) I have decided to make a costs order requiring the husband to pay £100,000 towards the wife’s costs of this application.

70. It is common ground that the sum of £5,000 has been paid on account and so £95,000 remains to be paid. The husband has sought time to pay - he suggests a first tranche of £30,000 on 9th December 2021 with the remaining £65,000 payable by 9th June 2022 with interest running at 4% from 9th December 2021. The wife does not agree and seeks the whole amount within 14 days with interest in default at the court judgment debt rate. I have considered both sides of this argument, but in the end have decided to make an order that the whole amount is paid by 9th December 2021 with interest in default at the court judgment debt rate. In reaching this conclusion I have taken into account that the husband has c£140,000 in a current account at the moment following a bonus of c £100,000 in July 2021 and an inheritance of c£150,000 earlier in the year (albeit that it is a joint account with his current partner), that he owns two motor cars (one worth £75,000 and the other worth £38,000, albeit under credit agreements), that he earns a very high salary (at least £400,000 per annum gross) and owns two properties (the second, in Cornwall, purchased earlier this year). I also agree with Mr George that it is high time that a line is drawn under this seemingly endless litigation.

ORDER

71. I would be grateful if Counsel now draft an order to this effect and which makes it clear that the objections to the original pension sharing order finally taking effect have gone. It is high time that this pension sharing order takes effect and is implemented.

72. There has been a subsidiary rumbling dispute about whether or not the other mechanical prerequisites to the implementation of a pension sharing order have been completed and I would like to nail this down when we meet formally to hand down this judgment (although the parties will have seen it electronically beforehand).

73. I propose to publish a redacted and anonymised version of this judgment on BAILII.

POST-SCRIPT

74. The facts of this case directly give rise to an issue which is highlighted in the PAG Report of July 2019 [14], but which has not I think had much public profile in the period since then - the ticking of the external transfer box in paragraph F of the pension sharing annex. Readers of the PAG Report have to be assiduous enough to reach Appendix V, paragraphs 41 to 44, to find this narrative, but it reads as follows:-

“V41. Consideration should be given to the removal of discretionary section F. It requires either the lawyer or the non-member spouse to tick the box to inform the pension scheme whether, upon the making of the Pension Sharing Order, the non-member spouse (transferee) receives an internal or an external transfer, where both options are available. Given the complexity of this issue, the availability of internal transfer options generally and the pension scheme’s legal obligation to offer an internal transfer if a scheme reduction factor is imposed, which could be after the annex has been sent to the court for approval, then the non-member spouse couldn’t possibly be in an informed position to make this decision, nor could their lawyers without breaking the law.

V.42 There is an FCA dispensation for regulated Financial Advisers dealing with Pension Sharing Orders where schemes insist on an ‘external transfer only’ option in that the Pension Sharing Order transfer is not deemed a regulated transfer. However, where an internal transfer option is available then the full, regulated transfer advice rules apply with the adviser first having to undertake an analysis of the client’s options and compare these with the benefits being given up.

V.43 If a family lawyer ticks the external or internal transfer box on behalf of their client then they may inadvertently give regulated transfer advice, which they are not authorised to do. Family Lawyers would be well advised in the meantime not to tick either boxes in section F to avoid that trap.

V.44 The situation could in any event have changed by the time the Pension Sharing Order takes effect and the implementation commences. At this point a regulated Financial Adviser is likely to be involved who would need to check the options available at the point of advice. It is suggested this section is removed from the annex as this is not the time to be making that decision.”

75. In the present case the letter from the pension administrators dated 2nd August 2016 (albeit written before the PAG report, but I understand these letters are still being written) appeared to require the wife to tick the external transfer box, even though at that stage there was no choice to make because (legitimately) only external transfers were on offer. Her lawyers obediently ticked the box, probably not understanding why they did not need to.

76. In the present case the pension administrators were only offering reduced CEs from 5th December 2016 onwards, yet they did nothing to draw the wife’s attention to this change and in particular to the crucial fact that this change meant that she did now after all have the option of an internal transfer. This seems to be exactly the sort of case envisaged by paragraph V44 above.

77. Although in the present case the pension sharing order did not take effect during the period that reduced CEs were being paid out, and so the potentially direct harm of an external transfer in this period did not actually occur, it is not clear what would have happened if the pension sharing order had taken effect in the course of 2017. Might the pension administrators have simply implemented the pension sharing order on the strength of the external transfer box ticked in different circumstances in 2016? Would the wife have actually been offered an internal transfer, as was her legal right? It is not at all clear what would have happened and there does seem to be something of a lacuna in the regulatory obligations to a transferee in the position of the wife in this situation.

78. Of course some of these dangers could have been avoided if the wife’s lawyers had properly understood these matters, but this case involves an instance where the lawyers did not properly understand the issue and, as a direct result of this lack of understanding, embarked on the course which has triggered the husband’s counter-application and which has done so much damage to this family.

79. The PAG Report suggested that paragraph F should be removed from the standard pension sharing annex Form P1. This has not yet happened.

80. In the meantime the PAG Report gave the warning: “Family Lawyers would be well advised in the meantime not to tick either boxes in section F”.

81. In my view these recommendations are given extra force by the facts of the present case.

His Honour Judge Edward Hess

Central Family Court

10th November 2021

[1] I want to give a full attribution to Mr Paul Cobley of Oak Barn Financial Planning who produced this helpful illustration and has given permission to me to use it in this judgment.

[2] I declare an interest as one of the co-authors of this book

[3] Welfare Reform and Pensions Act 1999, section 29(2)

[4] Welfare Reform and Pensions Act 1999, sections 29(7) and 34.

[5] See, for example, Culverwell v Teachers’ Pension Scheme (2012) 13 November, ref 82981/3

[6] See, for example, Staley v Marlborough Investment Management Limited Retirement Scheme (2012) 31 July, ref 81482/2, where the judgment was reserved between 28 July and 24 October and the order approved on 20 November

[7] See Slattery v Cabinet Office (Civil Service Pensions) and Another [2009] 1 FLR 1365

[8] Welfare Reform and Pensions Act 1999, sections 29(4), 29(5) and 29(8)

[9] See, for example, Crabtree v BAE Systems Executive Pension Scheme (2008) 19 May, ref S00522, and Culverwell v Teachers’ Pension Scheme (2012) 13 November, ref 82981/3

[10] Occupational Pension Schemes (Transfer Value) Regulations 1996 regulation 8 and schedules 1 and 1A as substituted by Occupational Pension Schemes (Transfer Value) (Amendment) Regulations 2008, regulation 4 and schedule1.

[11] Welfare Reform and Pensions Act 1999, schedule 5, paragraph 8 and The Pension Sharing (Implementation and Discharge of Liability) Regulations 2000, SI 2000/1053, regulation 16

[12] Welfare Reform and Pensions Act 1999, schedule 5, paragraph 1(2) and The Pension Sharing (Implementation and Discharge of Liability) Regulations 2000, SI 2000/1053, regulation 16

[13] The Pension Sharing (Implementation and Discharge of Liability) Regulations 2000, SI 2000/1053, regulation 16

[14] I want to declare an interest as the co-chair of PAG