Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

England and Wales Court of Protection Decisions

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> England and Wales Court of Protection Decisions >> AB, Re [2020] EWCOP 47 (25 September 2020)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWCOP/2020/47.html

Cite as: [2020] EWCOP 47, [2021] COPLR 30

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

This judgment is covered by the terms of an order made pursuant to Practice Direction 4C- Transparency. It may be published on condition that the anonymity of the incapacitated person and members of her family must be strictly preserved. Failure to comply with that condition may warrant punishment as a contempt of court.

MENTAL CAPACITY ACT 2005

42-49 High Holborn, London, WC1V 6NP |

||

B e f o r e :

____________________

| IN THE MATTER OF (1) M (2) S |

Applicants |

- and - |

| (1) AB (by her Litigation Friend the Official Solicitor) (2) London Borough of Southwark |

Respondents |

|

____________________

Mr. John McKendrick QC (instructed by Mackintosh Law) appeared for the First Respondent

Ms. Sian Davies (instructed by Southwark Council) appeared for the Second Respondent

The hearing was conducted in public subject to a transparency order made on 9th September 2020. The judgment was handed down to the parties by e-mail on 25th September 2020. It consists of 34 pages, and has been signed and dated by the judge.

____________________

Crown Copyright ©

- AB is presently living and being cared for at B Care Home in London, pursuant to arrangements made and authorised by the Second Respondent Local Authority but contrary to the wishes of the Applicants.

- In these proceedings the Court is asked:-

- Capacity is not in issue.

- These proceedings have been conducted in the midst of the covid-19 pandemic, which has had an impact on the arrangements possible for contact between AB and M whilst the applications are under consideration, and also on the way the proceedings have been conducted. The initial directions hearing was held remotely, by telephone; and this hearing has been a 'hybrid' of attendance mostly in person but the Second Applicant, the expert witness and a social work manager by Cloud Video Platform.

- I have considered all the documents in the hearing bundle, which is made up of 2 lever arch files, including:

- I heard oral evidence from Helena Keech, M and – remotely, via CVP - Marc Bekerman.

- I heard submissions from M, S (remotely, via CVP), Mr. McKendrick QC and Ms. Davies.

- I engaged directly with AB via Microsoft Teams remote link on the second morning of the hearing. She was accompanied by a nurse and the manager of the placement where she presently lives. Her solicitor was also part of the Teams call, from the courtroom.

- AB was born in the USA on 15th September 1998, and so is now 22 years old. Her mother, M, is a British citizen who was taken to live in the USA by her own mother sometime in the 1970s [A2]. S is AB's sister.

- AB suffered brain injuries at birth. She has cerebral palsy, microcephaly, bilateral dislocated hips and scoliosis, and is wheelchair bound. She has significant visual impairment and a history of seizures (although these appear now to have resolved.) She receives nutrition through a PEG feed. She is non-verbal.

- At present little is known of AB's life in the USA except that she was in the care of her mother. In written documents [A2] M describes herself as "a New York trained nurse assistant with three years college" and says she "operated a licensed NY State home for veterans, the elderly, and adults with learning disabilities…. managed a care home for wayward teen mothers…is a bilingual Spanish/English tutor, aerobics instructor, and West Coast Swing wheelchair dancer with her daughter." In oral evidence M made no mention of these occupations and described only dependence on state benefits for housing and income.

- S continues to live in the USA. She is described by her mother [A2] as "a SUNY college graduate and HR professional. She is a young adult who manages her own life in the States. She typically provides extended respite for her sister when needed."

- AB's father, T, has played no part in these proceedings. His whereabouts are unknown to the Respondents [D107]. M has told a social worker that he was abusive.

- On 29th November 2019 M and AB flew to the UK, on one-way tickets [D46]. Although they arrived via Gatwick airport, it would appear that they went initially to Aberdeen, where the City Council paid for their temporary accommodation in a hotel and a rail ticket back to London. Thereafter, they stayed for a short time with M's sister, then her niece. Latterly they stayed with M's aunt, in her third floor flat with no lift.

- On 14th December 2019 AB was taken to King's College Hospital in an ambulance. M was concerned that AB had been "making unusual crying sounds during a feed" [A3]. The hospital subsequently raised safeguarding concerns about M's feeding practices. AB was considered medically fit for discharge by 18th December but she remained an inpatient for almost three months because there was no accessible home to which she could be discharged.

- On 9th March 2020 AB was discharged to B Care Home. Initially M stayed with her there, apparently because she had no other accommodation and expected to be allowed to stay with her daughter. The covid-19 emergency lead B Care Home to enforce restrictions on visitors. Police were involved in removing M.

- A Standard Authorisation in respect of deprivation of liberty in AB's living arrangements at B Care Home was granted on 9th April 2020, with effect for 12 months [C29]. It is a condition of the Standard Authorisation that "[t]he Managing Authority … facilitate regular telephone contact between [AB] and her mother whilst [M] is unable to visit her in person, at a minimum level of one telephone call per week." M is appointed as AB's Relevant Person's Representative.

- M is presently living in accommodation which was provided to her following an application for assistance as a homeless person under Part 7 of the Housing Act 1996. The Second Respondent has informed the court that M has been assessed as "not in priority need;" and that she had a statutory right to seek a review of that decision but has not done so. The duty to accommodate has now come to an end. Eviction proceedings have not been commenced only because of the general moratorium of such proceedings in circumstances of pandemic, which moratorium is expected to expire imminently. M considers that she has done what is required to challenge any decision that she cannot continue to live in her current accommodation but she also contends that she should be assessed for and provided with accommodation suitable for AB to live with her.

- Proceedings in the UK were begun when M and S made a COP1 application [B17] dated 29th May 2020 seeking:

- In Annex B to the application M informed the Court [B3] that:

- There was filed with the application numerous documents, including

- By order made on 10th June 2020 [B33] the application was stayed pending the filing of further documents specified in a schedule.

- Meanwhile, the London Borough of Southwark had been notified of the application and filed a COP5 Acknowledgment [B29] informing the Court that it "is currently providing care to [AB] and so has an interest in the application's outcome." The Local Authority indicated that it "supports the application made under schedule 3, in so far as it will provide clarity regarding recognition of the Order but are (sic) of the view that any other matters to be determined…should be determined under section 21A."

- On 19th June 2020, following referral of further documents filed by M (not fully compliant with the schedule) and the Local Authority's COP5, an order [B35] was made which essentially progressed the matter as a challenge to the Standard Authorisation pursuant to section 21A of the Mental Capacity Act 2005. The Official Solicitor was invited to act as Litigation Friend for AB and the matter was listed for a directions hearing, to be conducted by telephone, on 7th July 2020.

- In the meantime, M and S filed a further COP1 application [B41], dated 30th June 2020, exactly repeating (at section 4.1) the terms of their first application. This time, in Annex B [B53] the Applicants informed the Court that

- An order was made on the papers on 2nd July 2020 [B61] providing for all applications to be considered at the hearing on 7th July.

- M then filed a COP9 application [B62] dated 3rd July 2020 seemingly objecting to the appointment of the Official Solicitor as Litigation Friend for AB and seeking to be allowed to fulfil that role herself.

- At the telephone hearing on 7th July 2020 the Official Solicitor acted as Litigation Friend for AB and arranged for her representation by Leading Counsel. An order [B67] was made which:

- Matters did not run smoothly to the next hearing. No fewer than thirteen COP9 applications were filed and resolved by me as follows:

- On the second morning of the hearing, three further COP9 applications were filed:

- Within the disclosure provided from the Second Respondent there was an e-mail from M dated 28th February 2020 which included the following account [D296]:

- It was as a result of this information, and its disparity with the impression generally being put forward by M, that AB's representatives sought – and were granted - permission to have direct discussions with the US courts. As a result, further information is now available about background events before AB was brought to the UK.

- The documents provided by the US court include the following:

- The Applicants seek the immediate return of AB to the care of M. She brought to the hearing on its second day the original Letters of Guardianship, bearing the raised seal of the US court. Although originally the Applicants relied on these orders as the basis for seeking AB's return to her mother's care, by the end of the hearing their position seemed to be that those orders could be disregarded. Intending that M and AB were now resident in the UK as a long-term arrangement, M considered that what she wants now is an English welfare deputyship under the Mental Capacity Act 2005 effectively to replace the American Letters of Guardianship. Understandably, the focus of the Applicants is very much on the immediate return of AB to the care of her mother, rather than the technicalities of procedure.

- In a "draft order" submitted by M, she has set out further provisions which she seeks, including:

- The Respondents are agreed that AB is still habitually resident in the USA, and any issues in respect of her long-term welfare fall to be considered first by the US courts. They contend that the jurisdiction of the Court of Protection is presently limited. They are further agreed that the question of recognition of the American Letters of Guardianship must be determined first, before any determination of the s21A application can be made. The Official Solicitor invites the Court to refuse to recognise the American Guardianship orders on grounds of public policy but to provide for the matter to be referred to the US court as soon as possible, making in relation to AB herself only such orders as are immediately necessary for her protection pending further order of the US court.

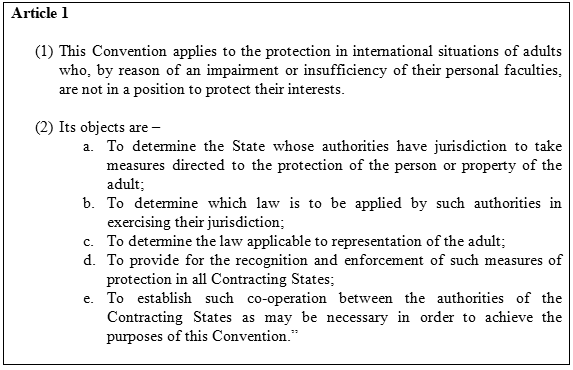

- On 13th January 2000 the Convention on the International Protection of Adults ("the Convention") was formally concluded at the Hague. The Convention makes provision for mutual recognition of protective measures by Contracting States.

- The Convention was accompanied by an explanatory report by Professor Paul Lagarde ("the Lagarde report"), which was reissued with amendments in 2017.

- The United Kingdom has signed the Convention but has ratified it only in relation to Scotland, not yet in relation to England and Wales[1].

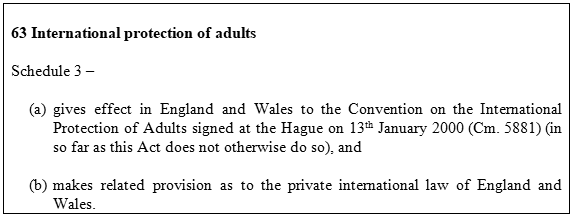

- The primary source of domestic law in England and Wales is Schedule 3 of the Mental Capacity Act 2005 ("the Act"), which is given effect by section 63 of the Act:

- Paragraph 2(4) of Schedule 3 provides that "an expression which appears in this Schedule and in the Convention is to be construed in accordance with the Convention."

- Schedule 3 of the Act is headed "International Protection of Adults." In broad terms, it contains two parallel sets of provisions:

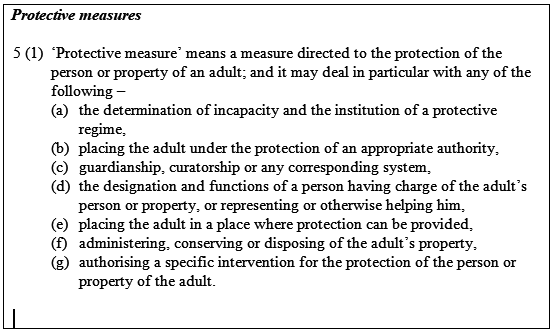

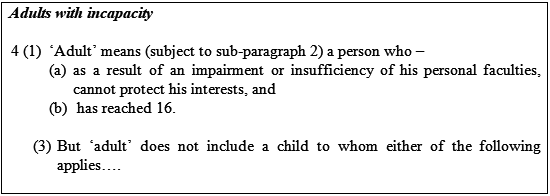

- Those parts of Schedule 3 which are currently effective apply to "protective measures" in respect of an "adult."

- The effect of those provisions of Schedule 3 which are in force can best be understood by considering the scope of the Court of Protection's 'full, original' jurisdiction, and its jurisdiction in respect of recognition of foreign protective measures, in turn; but key to both is the concept of 'habitual residence.'

- It is reasonably settled that the meaning of "habitual residence" under the Act should be the same as is applied in other (family law) instruments such as the 1996 Hague Convention on the International Protection of Children, and EU Council Regulation 2201/2013 ("Brussels IIa").[2] "Habitual residence" is therefore a question of fact, to be determined by reference to the conditions and reasons for the person's stay in a particular jurisdiction, its duration, and any other factors which make clear that the person's presence is not in any way temporary or intermittent.

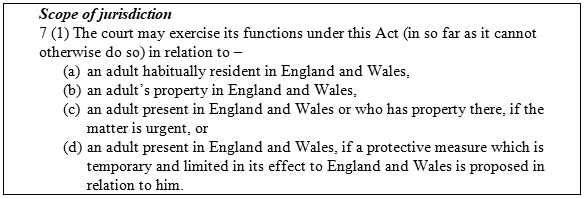

- The scope of the 'full, original' jurisdiction of the Court of Protection – that is, its powers to make declarations and orders under sections 15 and 16 of the Act – is set out in paragraph 7(1) of Schedule 3:

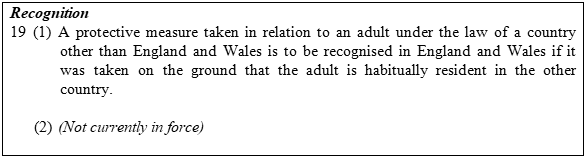

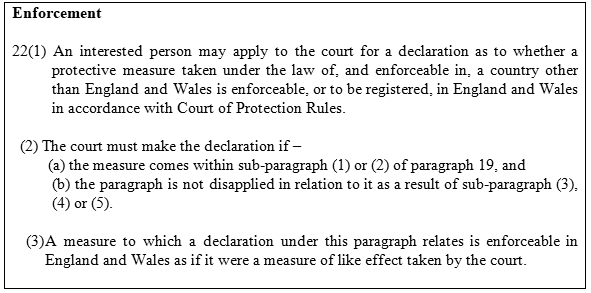

- Additional powers to recognise and enforce foreign protective measures that relate to adults, irrespective of any reciprocal arrangement, are set out in Part 4 of Schedule 3. The basic provisions are in mandatory terms:

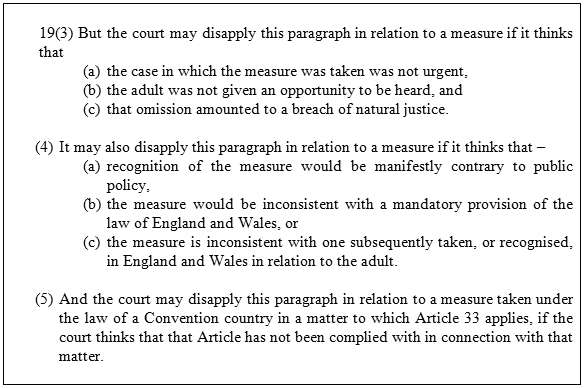

- Paragraph 19 of Schedule 3 goes on to provide for circumstances in which the Court of Protection may disapply the mandatory provisions:

- I have considered various authorities as to the effect of these provisions and how they should be applied:

- In respect of 'public policy' considerations, Mr. McKendrick referred me to two additional authorities:

- In terms of procedure, I remind myself of the specific rules in respect of applications in connection with the Court's additional jurisdiction under Schedule 3 of the Act. They are set out in Part 23 of the Court of Protection Rules 2017 and Practice Direction 23A.

- Paragraphs 7 – 12 of the Practice Direction set out what is required from the applicants:

- Paragraphs 13 – 17 of the Practice Direction set out the procedure to be followed by the Court:

- Paragraphs 18 – 20 of the Practice Direction make specific provision for the procedure to be followed where issues of habitual residence arise:

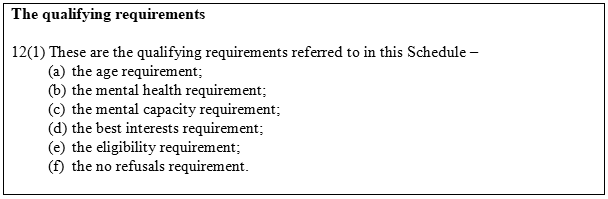

- The qualifying requirements for an authorisation under the DOLS scheme are set out at paragraph 12 of Schedule A1:

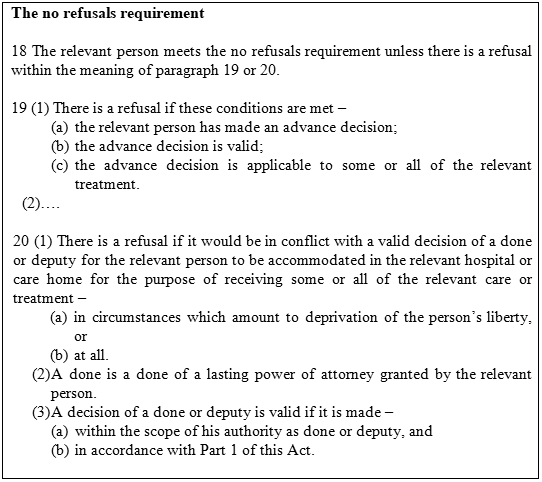

- The 'no refusals requirement' is defined at paragraphs 18 - 20 of Schedule A1:

- The Applicants are unrepresented in these proceedings.

- Mr. McKendrick notes in his position statement (at paragraph 22) that "M has clearly been informed of her right (as AB's RPR) to non-means tested legal aid." On a previous occasion[3] I have noted scope for argument as to whether this interpretation of the Civil Legal Aid Regulations is correct in circumstances where, as here, the RPR is representing their own position and the protected person has independent representation taking a different approach. Nonetheless, it is a position which solicitors approached by M to act for her in these proceedings would be expected to explore.

- M was calm, courteous and self-possessed throughout the hearing. When invited to explain why she was unrepresented, she told the Court that "I haven't found anyone I could instruct who would take my case…they had changed their mind and made other claims…. They had wanted so much information…there seemed something corrupt about what they've done." When asked to identify solicitors' firms which she had approached but apparently declined to act for her, M was unable to recall any names except for the firm which acts for AB herself, "Wainwright" or "Oscar."

- It is notable from the documents disclosed by the US court that M has previously talked of instructing an attorney, and then shown no sign of actually having done so.

- I am satisfied that acting in person is very largely an approach which M has chosen. It is her right to do so. In my judgment, her lack of representation is not a reason for the proceedings not to progress.

- I have considered whether this matter ought to be determined by a Tier 3 judge. Mr. McKendrick QC explained that this was also considered at the telephone directions hearing before the Tier 1 judge, when the matter was listed before me. No party now seeks vertical transfer. Particularly fortified by paragraph 17 of PD 23A, I am satisfied that it is not necessary to import the inevitable delay which transfer to a Tier 3 judge at this point would bring, and I may deal with these proceedings today.

- It is not in dispute that AB was habitually resident in the USA up to 29th November 2019, having lived there all her life since birth. The question to be determined is whether her place of habitual residence changed when M brought her to the UK or subsequently; and that question turns, in my judgment, on whether M was acting properly within the scope of her Letters of Guardianship.

- The expert evidence: In his written report Mr. Bekerman confirmed [F8] that the photocopied documents provided by M "do appear to be consistent with the Court documents relating to Article 17-A guardianship which I have seen from other New York State Courts" and explained [F2] that

- Since writing his report, Mr. Bekerman had been provided with a copy of the further information disclosed by the US Court and exhibited to the statement by AB's solicitor. He explained orally that the LETTERS OF GUARDIANSHIP (PERSON ONLY) 17A dated 1st February 2017 [D397] is the effective authority. He confirmed that such authority does extend to deciding where AB lives and how she is cared for, "subject to the Court's power to supervise the Guardian."

- Mr. Bekerman confirmed that M's 'Notice of Motion' e-mail [B206] should have had no effect because it is not in the proper format, has no supporting papers and identifies no respondents. He speculated that it "may have been enough for Erie to speak to Monroe about transfer." He confirmed that "usurpment" is not a term of the relevant statute, and 1750-b is "simply for healthcare decisions."

- Mr. Bekerman explained that a petition for discharge of guardianship is "filed" and an order is "issued"; and a copy of the petition would not usually be provided to the Guardian whose discharge is sought until the order is issued. Asked about why there was apparent delay between the date of the petition [4th October 2019 – D412] and the date of the order [9th December 2019 – D417] he explained that the court may have had a backlog or there may have been "concerns," possibly to do with the Letters having been issued from the Erie County Court but the petition issued in the Monroe County Court.

- Asked about the apparent withdrawal of the petition for discharge, Mr. Bekerman noted that there appeared to have been "an informal withdrawal" [by e-mail – D431]. His view was that "it may be best practice to get a judicial order but I don't know if it's necessary." He confirmed that, AB now having been located, the discharge proceedings could be restarted.

- The Applicants' evidence: M herself has given a number of explanations of how she came to move to the UK with AB:

- In respect of historic concerns about her care of AB, M denied having previously moved AB within the state of New York because of adverse allegations. Asked about the report dated 2/1/2012 [D372] which records her stating that she 'was leaving the area so as not to "just feed into someone else's agenda" with respect to [AB]'s needs', M acknowledged that "this sounds like something I could have said" but she considered that the 2012 allegations "were not supposed to be listed as substantiated."

- Asked about Marcia Rivera's report of October 2019, M denied having received it before it was disclosed in these proceedings, and said she disagrees with most of it – "she kept coming to our apartment. The reasons she was coming made no sense to me." M considered that "No, I didn't know they had concerns because I'd answered her questions." She later said that she "was aware of the opposite of concerns – these questions didn't have anything to do with wanting to help. I was not aware of the risk of guardianship being taken away because it was just an insane situation."

- However, she acknowledged that "yes, I was aware of the possibility of proceedings… It's fair to say that when I approached Erie County Surrogate Court they suggested I get representation…[and] they said I could get it transferred to Monroe [but] I didn't make an application." She denied having seen the transfer order [D415] or the show cause order [D417] and maintained that "as of November 2019, I had no awareness of proceedings." She did however consider that "they were doing something illegal, so I complained to the Governor's Office. No, I didn't leave the jurisdiction because of this, because he fixed it." When S told her about the show cause order, having received a copy in the post, M "had no interest" and told her "just throw it out in the trash where it belongs."

- When Ms. Davies suggested that there was a pattern of M moving when social services raised concerns, M replied that this was "101% not true."

- M was asked about the apparent lack of planning of arrangements for care of AB in the UK. She explained that she had planned to stay with family members, who were "prepared to help because they knew we were in crisis." The hotel stay in Aberdeen was because social services there "offered" to pay. She considered that she had everything she needed medically for the care of AB.

- M described her decision to live in the UK as "permanent" but also that her future plans, "depend on what happens with my daughter." She explained that she refused to leave B Care Home without police intervention because she felt this was necessary to make clear that she was not leaving her daughter voluntarily. She confirmed that she has been living in accommodation provided by the Local Authority since April 2nd, and she does not have accommodation available to her in the US. Later, she said that she "is staying in Britain, and I want [AB] to stay with me."

- S read her statement by way of submissions. She also explained that, in her view, the UK is AB's "new home." She described her family has having "already relocated to the UK before we even knew about anything filed at Monroe. My mother had authority to move my sister."

- The Local Authority contends that there is a pattern of M leaving a jurisdiction to avoid proceedings, and her move to the UK with AB is part of that pattern. Ms. Davies emphasised the shallow planning for care of AB on arrival in the UK – no settled accommodation, no medical arrangements, no income – and the speed of breakdown in AB's care as a result.

- The Local Authority's position is that AB's current connection to the UK is very weak – she has no settled home here other than the care home, she has spent all her life until November 2019 in the US, she has family members in the US (sister and father) as compared to more distant relatives (apart from her mother) in the UK none of whom have provided any sustained support. The real intention, it is said, of AB being brought to the UK at all was to avoid imminent proceedings for the discharge of guardianship powers, and that kind of intention cannot be a sound basis for a change in habitual residence.

- The Official Solicitor's position is also that AB was and remains habitually resident in the US. The OS accepts that M was properly granted Letters of Guardianship which include authority to determine where AB lives but, whilst emphasising for M's benefit that there is no suggestion she has acted "criminally," Mr. McKendrick submits that her removal of AB from the US was not a valid exercise of guardianship powers because it was done "in bad faith" – M knew that there was an investigation underway in the summer of 2019, knew she was at risk of losing guardianship powers, and moved in an attempt to evade that possibility becoming reality. Furthermore, when S received the order of 9th December 2019, M's response was to disregard it; and, by failing to mention in her applications to this court anything about that order, she has also come to the English court in bad faith.

- Conclusions: I listened very carefully to M's oral evidence. The impression I formed was of an intelligent and genuinely caring mother but also one who is highly distrustful of public authorities, unable or unwilling to understand that they may have legitimate concerns about AB's wellbeing or a valid viewpoint about her welfare.

- I do not accept M's denial that her move to the UK was connected with the prospect of US proceedings to challenge her guardianship of AB. On her own account M was clearly aware of, and resented, Marcia Rivera's interest in the care of AB. It is possible that M genuinely did not understand her concerns but it is clear to me that M did understand that Marcia Rivera's involvement with AB represented a threat to her own authority to make decisions in respect of her daughter, and that court proceedings were imminent. I am satisfied that, as she had done before, M's response was to move AB out of the jurisdiction of the court, consciously in a bid to avoid its exercise.

- M's decision to move AB to the UK was therefore not a proper exercise of legitimate powers, and not effective to change AB's habitual residence.

- Moreover, AB's circumstances since her arrival in the UK cannot be said to have settled such that her habitual residence has changed by passage of time notwithstanding the bad faith in the arrangements for her arrival. Any support that AB has received from wider family has been extremely transient. She lives in a care home precisely because she had no other appropriate accommodation. She is not integrated into the community beyond the care home placement.

- In my judgment, AB presently remains habitually resident in the USA.

- It follows from this conclusion that, pursuant to paragraph 7(1)(c) and (d) of Schedule 3, this court may only exercise its 'full, original jurisdiction' in respect of AB if the matter is urgent or if a protective measure which is temporary and limited in its effect to England and Wales is proposed in relation to her.

- M has expressed concerns about AB's current situation but there is no evidence of any immediate threat to her life or safety and, I am satisfied, no immediate need for further or other protection. It is of course important that decisions about AB's long-term welfare are taken as soon as possible but there is no 'urgency' in the sense identified by Cobb J in TD & BS v. KD & QD. At this point, the jurisdiction to determine wider welfare issues must be yielded to the courts of New York State. This court should only make such temporary and limited provision as is required to safeguard AB whilst that process is undertaken.

- I am acutely conscious of the mandatory nature of paragraph 19(1) of Schedule 3 and the requirement to "work with the grain of the order" of a country whose legal systems, laws and procedures are closely aligned to our own. It has not been suggested by any party that either the Erie County Surrogate Court or the Monroe County Surrogate Court is anything other than "an experienced court with a sophisticated family and capacity system."

- Nonetheless, the position statement filed on behalf of AB shortly before the hearing set out the Official Solicitor's preliminary position that I should disapply the mandatory recognition requirement on the basis that recognition would be contrary to public policy. At the close of the first day of the hearing, I asked Mr. McKendrick to consider further the policy which is said to be offended, for further submissions at the end of the hearing.

- In closing submissions, Mr. McKendrick identified the policy of "judicial comity." His argument is that, if M knew that her care of AB was being investigated with the possibility of steps to discharge her guardianship and she left the USA deliberately to avoid that possibility, recognising her guardianship now would amount to failure of judicial comity with the Monroe Surrogate Court. In effect, the determination of issues put before Monroe Surrogate Court has been thwarted by actions of M taken in bad faith. Recognition of the guardianship authority in the face of frustrated proceedings to discharge it would endorse the bad faith of M. It is not the measure (ie the Letters of Guardianship) which is manifestly contrary to public policy but rather the recognition of it in circumstances where the US court was actively engaged in the process of considering whether the measure should be discharged immediately before AB's was removal from its jurisdiction.

- I had also asked Mr. McKendrick to consider whether the recognition application could or should be adjourned, or determined on an interim basis. His submission was that there could be no adjournment of the recognition application, and no "interim" refusal to recognise, because such would be contrary to the mandatory nature of paragraph 19(1). If the purpose behind either adjournment or interim decision was to revisit the question of recognition in the light of the US court's determination of the discharge petition, a better approach would be to require a new application for recognition if the discharge petition failed. Such application would then be free of any question of 'bad faith'.

- Finally, I had asked Mr. McKendrick to consider whether this court could, or should, recognise the US Letters of Guardianship but then also suspend them. Mr. McKendrick professed himself "not at all confident" that this court has such power, although he also properly acknowledged that paragraph 128 of the Lagarde Report[4] seems to suggest that this may indeed be permissible.

- I am most grateful to Mr. McKendrick for his submissions on these points, which I have found of great assistance.

- In my judgment, it is important to consider the effect of recognising the Letters of Guardianship granted to M, which would be to recognise that M has authority to decide where AB lives and how she is cared for[5]. In reality, M would decide that AB should immediately leave the care home to live with her, whatever the insecurities of M's own position and the limitations of her resources to provide care at the moment.

- The American court has already been asked to determine an application to revoke M's authority to make such a decision. It has only been prevented from doing so by M removing herself and AB from its jurisdiction. In those circumstances, I am clear that it would be contrary to the requirements of judicial comity to recognise now that very authority which the American court has been asked to review. I have come to the firm conclusion that it is clearly right and just, at this point, to disapply the requirement of mandatory recognition on the grounds of the policy of judicial comity. Such conclusion is not a reflection on the merits of the Letters of Guardianship themselves, or the powers of the US court to grant such Letters. Rather, it is a reflection of the circumstances in which the application for recognition comes to be determined by this court.

- It follows from that conclusion that I should dismiss the application for recognition.

- To be clear, I make no decision on whether this court could recognise the foreign protective power and then immediately suspend it. That decision will likely fall to be made in the circumstances of another case, on another occasion. Furthermore, there is nothing in the dismissal of this application for recognition which prevents a further application for recognition of the same Letters of Guardianship in the light of any future decision by the US court.

- Since it invokes Article 5 of the European Convention on Human Rights, the challenge to the Standard Authorisation in respect of deprivation of her liberty in AB's current living arrangements is not dependent on habitual residence. At least in respect of the qualifying requirements and pending further order of the US court, that challenge can and should be determined by this court at this stage.

- There are two qualifying requirements which are subject to challenge in respect of the current standard authorisation for deprivation of AB's liberty: the 'no refusals' requirement and the 'best interests' requirement.

- On a narrow interpretation of paragraph 20 of Schedule A1, M does not come within the class of persons whose valid decision could mean that AB failed to meet the 'no refusals' requirement because M is not and never has been "a donee of a lasting power of attorney" granted by AB or "a deputy" within the meaning of the Act.

- However, the authority encompassed by Letters of Guardianship granted by a US Court is clearly comparable to English deputyship (it would appear, even wider.) Following the principle of recognition by operation of law, as explained at paragraph 116 of the Lagarde Report, M was in an equivalent position to an English deputy with authority to determine residence, at least until she took a step towards enforcement. A narrow interpretation of paragraph 20 may therefore be vulnerable to criticism of inconsistency with the mandatory nature of the recognition provisions, and a wider interpretation – which considers whether M falls within the definition of persons who may make a valid decision for the purposes of the 'no refusals' requirement- ought to be considered.

- M has taken steps towards enforcement of her Letters of Guardianship, by making her application to this court for recognition. Her application has been refused. Her authority is not recognised. In my judgment, it follows that – whether a narrow or a wide interpretation of paragraph 20 of Schedule A1 is adopted – any decision which M may have taken that AB should live with her and not at B Care Home is not such as to count as a 'valid decision' for the purposes of the 'no refusals' requirement.

- In respect of the current standard authorisation in respect of AB, the 'no refusals' requirement is satisfied.

- The Applicants contend that AB's current living arrangements are not in her best interests. At this point, I do not agree. M has no secure accommodation suitable for meeting AB's needs. The events of December 2019, when AB required hospital admission so very rapidly after her arrival in the UK, demonstrate that M would presently struggle to keep AB safe and well. As a protective measure on a temporary basis pending further decision of the US court on wider welfare issues, I am satisfied that it is in the best interests of AB to remain living and receiving care at B Care Home.

- In respect of the current standard authorisation in respect of AB, the 'best interests' requirement is satisfied.

- The current standard authorisation is effective until 8th April 2021. There is no need for the court to make any further provision than to dismiss the s21A challenge.

- AB remains habitually resident in the USA, and this court yields jurisdiction in respect of her welfare to the courts of New York State. The application for recognition of Letters of Guardianship granted to M in respect of AB's person is refused on the grounds of public policy. The qualifying requirements for standard authorisation of deprivation of liberty in AB's present living arrangements are met, and the challenge to the current authorisation is dismissed.

- AB's representatives are authorised and required forthwith to disclose any document filed or order made in these proceedings, and this judgment, to the Monroe County Surrogate Court for the purposes of that court taking such further steps as it considers appropriate in respect of AB.

- The Second Respondent is authorised and required forthwith to disclose any document filed or order made in these proceedings, and this judgment, to the Monroe Adult Protection Services, for the purposes of taking such further steps as the APS considers appropriate in respect of AB.

- In respect of these proceedings, I shall list a further attended hearing on 25th November 2020 at 10.30am. At that hearing, the court will consider any further orders of the US court and make such orders as may be appropriate. In the event that developing pandemic restrictions prevent the hearing taking place by attendance at First Avenue House, the parties should make a timely COP9 application seeking further directions for a remote hearing, to be agreed if possible.

- In the meantime, I am grateful to Ms. Davies and the London Borough of Southwark for confirming that a named officer of the housing department will contact M within 28 days for the purposes of providing her with support to make such applications or responses as are necessary to pursue all proper avenues for obtaining secure accommodation. I encourage M to engage with that person.

- AB's representatives urge that Speech and Language Therapy assessment of AB is essential to ensure that AB's ability to communicate is maximised. I endorse that assertion. When I met AB virtually, she had the caring attention of a nurse. AB smiled frequently but she also groaned, and it was not possible for me to discern if either expression was a response either to our engagement or to her situation generally. Expert assistance in maximising her communication can only further her best interests and should be pursued as far as possible.

- I have expressed concern at the limited contact between M and AB at present. I acknowledge that the covid-19 pandemic has presented extra difficulties in the arrangement of contact, and that M has not taken up all the contact which she could have (apparently on the basis that she does not feel it is fruitful to make a three hour round trip only to spend a limited time with AB and not be able to take her 'home.') However, the social worker was clear that there is no impediment to increased contact between M and AB, within any pandemic restrictions which may be imposed from time to time. I endorse the advocates' suggestion that a recital should be included in the order made today setting out the opportunities for contact, and how M may avail herself of them.

- Finally, there is lack of clarity as to AB's status within the UK. The Applicants have described her as a British citizen on numerous occasions but no confirmation of that status has been provided. It may be that she is entitled to apply for such status. M has informed the court that both her own and AB's passports are currently with the UK Passport Office. I will therefore make a third party disclosure order providing for HM Passport Office to disclose to AB's representatives copies of all documentation relating to any application made in respect of AB (with liberty to apply to vary the order on 7 days notice). I also authorise AB's representatives to receive from the Passport Office or any other person any passport of AB, to be kept in safe custody pending any further order. For the avoidance of doubt, AB is not to be removed from the jurisdiction of this court without further order.

- Counsel are requested to file draft orders giving effect to this judgment (agreed if possible), for approval on the papers.

Her Honour Judge Hilder:

A. The Issues

a. to recognise Letters of Guardianship granted by Erie County Surrogate Court, State of New York, USA, which confer authority on M to make decisions in respect of AB's person; and

b. to determine a challenge to the Standard Authorisation in respect of deprivation of liberty in AB's current living arrangements by returning AB to the care of her mother, M.

B. Matters considered

a. Filed by the Applicants

Statements by M dated 29th May 2020 [D1], 16th June 2020 [D90], 20th August 2020 [D154] and 7th September 2020

Statement by S dated 29th May 2020 [D5]

b. Filed on behalf of the First Respondent

Statements by Zena Bolwig dated 1st September 2020 [D289] and 3rd September 2020

c. Filed by the Second Respondent

Statements by Helena Keech (social worker) dated 29th July 2020 [D107] and 11th September 2020

Statement by Helena Crossley dated 26th August 2020 [D284]

d. Expert report

Marc Bekerman dated 27th August 2020 [F1]

e. Capacity assessments

DOLS form 3 by Adedayo Akintola, social worker, dated 6th January 2020 [B173]

DOLS form 4 by Dr. Kassim dated 1st January 2020 [C1]

DOLS form 3 by Eleanor Greenwood, social worker, dated 8th April 2020 [C15]

C. Factual Background

D. These proceedings

"An Order to uphold United States Deputies:

---Section 15(1)(c) of The Act, which states, I am acting lawfully in England and Wales when exercising authority under my Deputyship.

---Schedule 3, Part 4 of the Act, the Proposed Protective Measure, wherein the Deputy for the person without capacity does not require approval of a foreign court to be regarded as the protective authority for the person without capacity."

"A legal Advance Directive was put in place in October 2014. The New York State Department of Health MOLST Form has been kept currently yearly at [AB]'s annual GP appointments; the last update being the 5th of November 2019. As Deputy I have been authorised and empowered by court order to make all decisions of Health and Welfare for [AB], who lacks all mental, intellectual and developmental capacity."

a. a photocopy of a Standard Authorisation in respect of AB's present living arrangements;

b. a photocopy of a document dated 25th September 2018 and headed "Surrogate Court of the State of New York Erie County Certificate of Appointment of Guardian"

c. a photocopy of a document dated 1st February 2017 with the words in the top right saying "AMENDED DECREE APPOINTING GUARDIAN PERSON ONLY Person With Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities File No. 2016-2399"

d. a photocopy of a document dated 27th October 2016 with the words in the top right saying "DECISION AFTER FAIR HEARING".

"The Borough is attempting to circumvent Tuesday's hearing by removing [AB]'s private home option, evict me from Hackney to a hotel room so there would be no place for [AB] to discharge. Again infringing on her right to have a private life and a Care Act Advocate. ARTICLE 8 and 14."

a. included a recital that "[w]hilst these proceedings are a deemed application pursuant to s21A Mental Capacity Act 2005 to challenge the second respondent's standard authorisation, the proceedings will need to consider the recognition of foreign protective measures, which are fundamental to the dispute under s21a, namely whether the 'no refusals' requirement pursuant to Schedule A1 is met";

b. dismissed the COP9 application in respect of the Official Solicitor's appointment as Litigation Friend;

c. provided for disclosure of the Second Respondent's social care records relating to AB and the filing of narrative evidence;

d. permitted the parties to instruct "an independent expert in the law of the State of New York, USA, to report on the validity of the orders obtained by M in relation to AB's welfare and the extent of the authority conferred on M…"; and

e. listed the matter for this hearing before me (to be conducted remotely).

Additionally, third party disclosure orders were made in respect of B Care Home, AB's GP and King's College Hospital, providing for disclosure to "the legal representatives of AB…and the legal representatives of M."

a. COP9 by M dated 15th July 2020;

b. COP9 by M dated 21st July 2020 [B87], seeking to vary the disclosure orders so that material was provided to her directly, as an unrepresented litigant;

c. COP9 by AB's representatives dated 21st July 2020 [B92], seeking discharge of the disclosure orders and the making of new disclosure orders providing for disclosure to AB's representatives only;

d. COP9 by M dated 23rd July 2020 [B98] asking the Court "to release [AB] from the care home";

e. COP9 by M dated 27th July 2020 [B109] asking for an order "that [AB] receive a further reduction of daily fat injection into her G tube";

f. COP9 by AB's representatives dated 28th July 2020 [B114], asking for the wording of the permission in respect of instruction of the independent expert to be varied so as to allow the instruction to proceed notwithstanding that M had not provided the documents required, and seeking permission "to discuss these proceedings with the relevant US courts, if necessary, so that orders and relevant papers can be obtained";

g. ORDERS made on 12th August 2020 which:

i. reciting that it was not apparent from the application what orders were sought, made 'no order' in respect of the COP9 identified in (a) above and also provided for this hearing to be conducted by attendance, not remotely [B122];

ii. discharged the third party disclosure orders and made new orders providing for disclosure to be to AB's representatives only, with provision for onward disclosure of any document relevant to these proceedings within 21 days of receipt [B124, B127 and B130];

iii. varied the provision in respect of the expert report as sought by AB's representatives and permitted AB's representatives to disclose documents to and discuss these proceedings with relevant court officers in the USA [B119];

h. COP9 by M dated 14th August 2020, requesting copies of disclosed material;

i. ORDER made on 18th August 2020 [B145] providing for other parties to file written responses to M's request at (h) above;

j. COP9 by AB's representatives dated 20th August 2020 [B147] seeking an additional third party disclosure order in respect of AB's new GP;

k. ORDER made on 26th August 2020 [B152] providing for disclosure by the new GP;

l. ORDER made on 26th August 2020 [B161], following receipt of written responses from the Respondents, refusing the application identified at (j) above;

m. COP9 by M dated 26th August 2020 [B163] requesting that no special arrangements be made for the attendance of Marie Ibe, the Second Respondent's social work manager;

n. COP9 by M dated 31st August 2020 [B168], again requesting the immediate release of AB into her care;

o. COP9 by AB's representatives dated 1st September 2020 [B196] seeking further directions in respect of the instruction to the expert;

p. COP9 by M dated 2nd September 2020 [B201] seeking orders "to stop [AB]'s whole case file being transferred to the US expert";

q. COP9 by M dated 4th April (but assumed to mean 4th September) 2020, seeking orders "to strike non guardianship documents obtained from Erie and Monroe Counties."

r. ORDER made on 8th September 2020, permitting the social work manager to attend the hearing by CVP, permitting AB's representatives to provide further documents to the US expert, refusing the application identified at (p) above, and providing for the applications identified at (n) and (q) above to be considered at the hearing.

a. COP9 by AB's representatives dated 10th September 2020 requesting a 'virtual' judicial visit to AB.

b. COP9 by M dated 10th September 2020, asking that the Court "address the breaches made by the Local Authority to our human rights and the illegally placed DoLS at KCH", that "my daughter is released into my care" and "that the court acts immediately without further delay."

c. COP9 by M dated 11th September 2020 asking the Court to dismiss the OS from the case, to order the expert to amend his report, to acknowledge COP9 submissions/supporting documentation/ UK deputyship application, to end the 'illegal confinement' of AB, to discharge AB back to her mother, to acknowledge 'perjured text statements' by the social worker, and to acknowledge the 'unheeded recommendations' of the Best Interests Assessor and the Independent Mental Capacity Advocate.

E. American proceedings

"I've protected [AB] from doctors her whole life. In the US however, there had been so much history of their failed attempts that they tried to prevent me from even getting simple monthly medical supplies, equipment, orthosis, and even her Pedia Smart formula for [AB]'s daily eating. I've seen plenty of it there and some of it continues here because elite doctors are part of the same western system. Every time we disagreed with their desired treatment for [AB] we were presented with ethic committee hearings, court dates, and challenges for guardianship."

a. A certified copy of a decree of dissolution of marriage between M and T, made by the Superior Court of Arizona in Maricopa County dated 2nd September 2010 [D327]. It is recorded that contact between AB and her father is to be supervised because "[T] is unstable career criminal with behavioral health issues and dependencies." Custody of AB was given to M.

b. A document headed "CPS INVESTIGATION SUMMARY" in respect of an "intake received 02/02/2012" [D367]. CPS refers to Child Protection Services. The summary records, in respect of AB as the child and M as the "subject of report," allegations of "Educational Neglect / Inadequate food, Clothing, Shelter / Inadequate Guardianship / Malnutrition, Failure to Thrive" all "Substantiated." The reason for closure is given as "Unable to contact/moved out of jurisdiction."

c. A document headed "CPS INVESTIGATION SUMMARY" in respect of an "intake received 04/15/2015" [D376]. The summary records, in respect of AB as the child and M as the "subject of report," an allegation of "Educational Neglect" to be "Substantiated." The reason for closure is again given as "Unable to contact/moved out of jurisdiction." The supporting narrative documentation records that "Mother moved to Buffalo NY on 4/15/2015. CPS sent CPS in Buffalo to see child and child was seen. No concerns were reported" and "Threat of harm is low. There is no harm at this time, as child is not attending school. Parents protective capacity is moderate. It appears that mother is meeting child's basic needs…" [D380]

d. A report dated 8th September 2016 [D389] by Leigh E. Anderson, who was appointed by the Erie County Surrogate Court as Guardian ad Litem for AB. It is said in the report that AB "was appropriately dressed and very clean. Her clothing and bedding was clean. The room was also spotlessly clean." It was recommended that the court grant "permanent Letters of Guardianship" to M.

e. Letters of Guardianship (Person & Property) 17A, granted by Hon Barbara Howe, Judge of the Erie County Surrogate Court, to M in respect of AB on 9th September 2016 [D392].

f. Letters of Guardianship (Person Only) 17A, again granted by Hon Barbara Howe, Judge of the Erie County Surrogate Court, to M in respect of AB, on 1st February 2017 [D397]. The document states "THESE LETTERS… authorise and empower the guardian…to perform all acts requisite to the proper administration and disposition of the person, property, or person and property (as stated above) of the ward in accordance with the decree and the laws of New York State, subject to the limitations, if any, as set forth above. The Limitation stated above is that "LETTERS OF GUARDIANSHIP PERSON AND PROPERTY ISSUED 9/9/16 HEREBY REVOKED."

g. An e-mail [B206] from M to Brandon Merrell timed at 12.39 on 16th August 2019 headed "NOTICE of MOTION" addressed to "Erie County Surrogate Court" stating that "I, [M] appointed guardian of [AB], respectfully request that the court uphold my guardianship and stop the usurpment of my authority to the detriment of [AB] Pursuant to SCPA Section 1750-b."

h. An affidavit dated 3rd October 2019 [D404] by Marcia Rivera, a Caseworker for the Adult Protective Services Unit of the Monroe County Division of Social Services, the caseworker assigned to AB. The report notes a referral made on June 12th 2019 expressing concerns "that [M] was not providing stable housing or proper care" for AB. It is reported that M "has been uncooperative with any assistance that has been offered to her, and uncooperative with the investigation of APS." Ms. Rivera concludes her report by "requesting the Court revoke the Letters of Guardianship granted to [M] and [S] and grant Letters of Guardianship to Corinda Crossdale, as Commissioner of Monroe County Division of Social Services…"

i. A Petition for Discharge of Guardians and Appointment of Successor in respect of AB [D410]. The date of the document is difficult to decipher but appears to be 4th October 2019.

j. An order of the Surrogate's Court in the County of Erie dated 19th November 2019 [D415], transferring guardianship proceedings to Monroe County Surrogate Court.

k. An order of the Surrogate Court in Monroe County dated 9th December 2019 [D416], appointing James D Bell as Guardian ad Litem for AB.

l. An order to show cause dated 9th December 2019 [D417] giving notice of a hearing in respect of the application to revoke the Letters of Guardianship granted to M and S listed at 9.30am on 19th December 2019. On the second page of that order it is "ORDERED, that pending further order of this Court, [AB] is not to be removed from Monroe County…."

m. An affidavit of service [D425] which appears to record that police were involved with assisting process servers to serve M with the order and court papers for the hearing on 19th December 2020 but her apartment was "found to be clear. Food in refrigerator – some clothing in closet – wheelchair in living room – not much furniture except a futon – no TV or electronics."

n. An e-mail [D431] apparently seeking the court's permission to withdraw the revocation application "in light of my office being unable to locate [AB] or her mother…"

F. Positions of the parties

a. that the Local Authority instruct the Housing Officer to issue a 'personal housing plan' for M and AB, with delivery of a hospital bed within 72 hours and transfer of AB's medical supplies, personal belongings and medical files with AB herself within 5 days;

b. the completion of passport applications made by M for herself and AB;

c. the completion of any outstanding paperwork for state benefits and the issue of a National Insurance number to AB;

d. payments to M and AB's accounts in respect of various benefits, and payment to Mencap of "four hundred and sixty-five pound sterling to properly establish the Discretionary Fund" for AB;

e. the issue of a Freedom Pass to M;

f. the assignment of a social worker "to begin and complete the process of assessment for all household needs, ongoing disability benefits, and support services, with funding package details….".

G. The Legal Framework

a. One set of provisions will incorporate the Convention into English domestic law. However, paragraph 35 of Schedule 3 provides that those provisions have effect only once the Convention has been brought into force, which is not yet the case in relation to England and Wales.

b. The other set of provisions is currently in force, based on but independent of the Convention. Effectively these provisions provide a set of rules for the recognition and enforcement in England and Wales of foreign protective measures, without any requirement for the foreign state to have assumed reciprocal obligations to the jurisdiction of England and Wales. They apply generally, in respect of States which have signed the Convention and States which have not.

a. The domestic definition of "protective measures" is set out in paragraph 5:

b. The domestic definition of "adult" is set out in paragraph 4:

a. Re MN [2010] EWHC 1926 (Fam): Hedley J considered the approach of the English court where an application was made for recognition of an order made by a Californian court requiring the return of MN to that state. MN had previously signed an Advance Healthcare Directive giving her niece PLH powers in respect of her welfare but it was the court order for return, and not the Directive, which was the subject of the recognition application.

The scope of the Directive was however considered in detail, including verbatim quote of "Part 3" – MN's "instructions for personal care." Hedley J concluded that "PLH had authority to determine where MN should live (until her displacement by the court) provided it complied with Part 3 and (importantly) it was a decision taken on good faith in the best interests of MN." The argument for recognition of the court order for return was set out in paragraph 18, including that the manner of removal raised serious questions over the making of the decision in good faith in the best interests of MN.

It was generally agreed that if MN's habitual residence was still California at the time when the order for return was made, then the English Court's powers were limited to those in Part 4 of the Act; but if MN's habitual residence was by then in England, the Court had it's 'full, original jurisdiction' under the Act. There was general acceptance (paragraph 21) that "mere passage of time if sufficiently long could effect a change of habitual residence even if the original removal were wrongful" but also that on the facts (just over 12 months) no such length of time had elapsed. Hedley J concluded (paragraph 22) that "the question of authority to remove is the key in this case to the question of habitual residence… It is well recognised in English law that the removal of a child from one jurisdiction to another by one parent without the consent of the other is wrongful and is not effective to change habitual residence…It seems to me that the wrongful removal (in this case without authority under the Directive whether because Part 3 is not engaged or the decision was not made in good faith) of an incapacitated adult should have the same consequence and should leave the courts of the country from which she was taken free to take protective measures. Thus in this case were the removal 'wrongful', I would hold that MN was habitually resident in California at the date of Judge Cain's orders."

On the other hand (paragraph 23), if MN's removal from California was a proper and lawful exercise of authority under the Directive, "it seems to me most probable that MN will have become habitually resident in England and Wales and this court will be required to accept and exercise a full welfare jurisdiction under the Act pursuant to paragraph 7(1)(a) of the Act." If MN was already habitually resident in England and Wales by the time the American court made the order for her return, then (paragraph 25)) "that will be the end of recognition and enforcement proceedings because the qualifying condition of paragraph 19(1) will not be made out."

The extent of the authority conferred by the Directive, and therefore the validity of its exercise, "are, of course, matters to be determined under Californian law" (paragraph 24). The alternative ways of resolving the question were either by determination by the US court within the American proceedings, or "the parties must agree on a single joint expert competent to advise the court on this point."

Whilst the question of the validity of PLP's actions under the Directive remained undetermined, Hedley J went on (at paragraph 26) to consider the mandatory nature of Schedule 3 paragraph 19(1) and the grounds for its disapplication. Particularly in regard to the 'public policy' ground, he observed that "A decision of an experienced court with a sophisticated family and capacity system would be most unlikely ever to give rise to a consideration of 4(a): the use of the word 'manifestly' suggests circumstances in which recognition of an order would be repellent to the judicial conscience of the court."

In turn this question raised the issue of the extent to which the Court takes into account the best interests of the protected person in an application for recognition. Hedley J concluded (at paragraph 31) that "… a decision to recognise under para 19(1) or to enforce under para 22(2) is not a decision governed by the best interests of MN …." and he gave three reasons for this: "First, I do not think that a decision to recognise or enforce can be properly described as a decision 'for and on behalf of MN'. She is clearly affected by the decision but it is a decision in respect of an order and not a person. Secondly, this rather technical reason is justified as reflecting the policy of the Schedule and of Part 4 namely ensuring that persons who lack capacity have their best interests and their affairs dealt with in the country of habitual residence; to decide otherwise would be to defeat that purpose. Thirdly, best interests in the implementation of an order clearly are relevant and are dealt with by para 12 which would otherwise not really be necessary."

If California continued to be the court of primary jurisdiction in respect of MN, Hedley J outlined (paragraph 34) three courses open to it:

i. it could continue the authorisation of the advocate appointed for MN to enforce the order for her return, "in which case this court will determine welfare under paragraph 12";

ii. it could allow MN to remain in England whist the Californian court considers a full welfare assessment, "in which case there is no real role for this court"; or

iii. it could invite the English court as a matter of urgency to conduct a full welfare enquiry into MN's best interests, "in which case this court could and would assume full jurisdiction under paragraph 7(1)(c) of Schedule 3. That of course would involve the Californian court yielding jurisdiction over the person of MN without prejudice to its jurisdiction over her estate."

Considering how enforcement of the American order to return MN to California would be implemented, Hedley J concluded (paragraph 35) that it would be for the Air Ambulance to decide how MN would be transported, and "[t]hey must treat her in reliance on Californian law or not at all." The English court should (paragraph 36) "look no further than the time that will be required to arrange an inter-partes hearing in Santa Clara….I am bound to assume, on the basis of habitual residence in California, unless and until Judge Cain indicates to the contrary, that her best interests are served by being in her own home in California."

b. Re PO [2013] EWHC 3932 (COP) : Munby J (as he then was) considered the provisions of the Lagarde Report in respect of habitual residence and observed that:

"18. In the case of an adult who lacks the capacity to decide where to live, habitual residence can in principle be lost and another habitual residence acquired without the need for any court order or other formal process, such as the appointment of an attorney or deputy. Here, as in other contexts, the doctrine of necessity as explained by Lord Goff of Chievely in In re F (A Mental Patient: Sterilisation) [1990] 2 AC 1, 75 applied… Put shortly, what the doctrine of necessity requires is a decision taken by a relative or carer which is reasonable, arrived at in good faith and taken in the best interests of the assisted person. There is, in my judgment, nothing in the 2005 Act to displace this approach…

20. Of course the doctrine of necessity is not a licence to be irresponsible. It will not protect someone who is an officious busybody. And it will not apply where there is bad faith or where what is done is unreasonable or not in the best interests of the assisted person. Thus there will be no change in P's habitual residence if, for example, the removal has been wrongful in the circumstances with which Hedley J was confronted in Re MN…."

c. Health & Safety Executive of Ireland v. PA & Ors [2015] EWCOP 38: Baker J (as he then was) considered the grounds for disapplication of the mandatory provisions of paragraph 19 in circumstances where an order had been made by the High Court of Ireland to move an incapacitous person from hospital in Ireland to a specialist placement in England where the care arrangements would amount to a deprivation of liberty. He observed (at paragraphs 36 – 37) that :

"36. This is an area where the principles of comity and co-operation between courts of different countries are of particular importance in the interests of the individual concerned. The court asked to recognise a foreign order should work with the grain of that order, rather than raise procedural hurdles which may delay or impede the implementation of the order in a way that may cause harm to the interests of the individual. If the court to which the application for recognition is made has concerns as to whether the adult was properly heard before the court of origin, it should as a first step raise those concerns promptly with the court of origin, rather than simply refuse recognition.

37. The purpose of Sch 3 is to facilitate the recognition and enforcement of protective measures for the benefit of vulnerable adults. The court to which such an application is made must ensure that the limited review required by Sch 3 goes no further than the terms of the Schedule require and, in particular, does not trespass into the reconsideration of the merits of the order which are entirely a matter for the court of origin…."

He further noted, at paragraph 94, that:

" …there is likely to be a wide variety in the decisions made under foreign laws that are put forward for recognition under Schedule 3. As the Ministry of Justice has observed, inevitably there may be concerns about some of the foreign jurisdictions from which orders might come. But as the Ministry also observes, taking account of such concerns is surely the purpose of the public policy review. Although no wide-ranging review as to the merits of the foreign measure is either necessary or appropriate, a limited review will always be required as indicated by the European court in Pellegrini. That will be sufficient to identify any cases where the content and the form of the foreign measure, and the process by which it was taken, are objectionable. It also seems to me that the circumstances in which Sch 3 is likely to be invoked, and the number of countries whose orders are presented for recognition, are likely to be limited. In oral submissions, Mr Rees pointed out that, in theory, the court could be faced with applications to recognise and enforce orders from any country in the world, including, for example, North Korea or Iran. That may be right in theory, but common sense suggests it is, to say the least, unlikely in practice, at least in the foreseeable future. And if such orders were to be presented for recognition, the public policy review would surely lead swiftly to identifying grounds on which recognition would be refused. It is much more likely that the orders presented for recognition will be those of foreign countries whose legal systems, laws and procedures are closely aligned to our own. Concerns of this nature can be addressed by admitting evidence of the process by which the foreign protective measures were made and general evidence relating to the legal system of the state that made the order."

d. TD & BS v. KD & QD [2019] EWCOP 56 : Cobb J considered an application in respect of QD, who had lived in Spain with his wife KD for several years and had developed dementia. The Applicants were QD's adult son and daughter from a previous marriage, who brought QD to the UK without the knowledge of his wife, and then sought orders from the Court of Protection that he reside at a care home in England, not return to Spain and have only supervised contact with KD. KD raised as a preliminary issue the question of whether the English court had jurisdiction at all.

Cobb J reviewed the authorities in respect of habitual residence (paragraphs 10 – 12) and came to the "clear conclusion that QD remains habitually resident in Spain. This court must therefore decline primary jurisdiction in accordance with the provisions of Schedule 3 of the MCA 2005, and should yield to the jurisdiction of the Spanish court." (paragraph 28). He described himself (at paragraph 29) as "influenced by the fact that, as an agreed fact, QD's move to this country was achieved by stealth. I do not find that TD and BS can avail themselves of the 'doctrine of necessity', to convert what was a wrongful act on their part into a justified act."

Cobb J was "absolutely clear" that it would not be appropriate to assume jurisdiction based on 'urgency' pursuant to paragraph 7(1)(c). Exercise of such jurisdiction would only be justified where substantive orders are necessary to avert an immediate threat to life or safety, or where there is an immediate need for further or other protection (paragraph 30).

His approach was therefore (at paragraph 32) "to exercise the limited jurisdiction available to me pursuant to Schedule 3, paragraph 7(1)(d), to make a 'protective measures' order which provides for QD to remain at an be cared for at [the English care home] and to continue the authorisation of the deprivation of his liberty there only until such time as the national authorities in Spain have determined what should happen next…. It is for the Spanish administrative or judicial authorities to determine the next step, which may of course be to confer jurisdiction on the English courts to make the relevant decision(s)."

a. Chaudhary v. Chaudhary [1984] 3 All ER 1017: where the Court of Appeal endorsed a decision of the first instance judge to refuse recognition of a talaq divorce on the ground of public policy. Wood J had observed in his judgment that "I do not believe that any judge would invoke the doctrine of public policy unless he felt that it was clearly right and just so to do." He relied on dicta enunciated by Donovan LJ in Gray (Orse. Formosa) v. Formosa [1963] P 259 at 271:

"If the courts here have, as I think they have, a residual discretion on these matters, they can be trusted to do whatever the justice of a particular case may require, if that is at all possible."

b. The Queen (on the application of Liberty) v. The Prime Minister & The Lord Chancellor [2019] EWCA Civ 1761 : in a single judgment the Court of Appeal made reference to the principle of judicial comity –

"As to comity, in the words of Lord Donaldson in British Airways Board v. Laker Airways [1984] QB 142 (at 185-6): "Judicial comity is shorthand for good neighbourliness, common courtesy and mutual respect between those who labour in adjoining judicial vineyards."

The s21A application

55. Following amendment with effect from 1st April 2009, the Mental Capacity Act 2005 provides a mechanism for authorisation of deprivation of liberty in the living arrangements of an incapacitous person at a care home or hospital - the 'deprivation of liberty safeguards', commonly known as "the DOLS scheme", which provisions are set out in Schedules AA1, A1and 1A to the Act. In essence, and subject to safeguards, the Supervisory Body (usually the Local Authority) of a care home or hospital may grant an 'urgent' or a 'standard' authorisation of the deprivation of liberty.

56. Pursuant to section 21A of the Act, the Court may review the lawfulness of the detention:

H. Procedural considerations in these proceedings

I. AB's habitual residence

"…a guardianship pursuant to Article 17-A is driven by diagnosis as opposed to the abilities and deficits of the person alleged to be under a disability. If the Surrogate Judge finds that the provisions of Article 17-A have been met and grants the requested guardianship, substantially all of the rights of the person determined to be under a disability will be impaired as the caselaw generally provides that the powers of a Guardian under Article 17-A cannot be tailored to the needs of a particular ward."

a. in an e-mail to her MP timed at 10.46 on 22nd March 2020 [B140], she says they "moved to England because of various social and political harassments. Ultimately, our disability benefits were confiscated, our apartment fees were moved to market rent, and we were left with nothing to live on. I was given the option to dispute these matters legally but had no hope of living functionally throughout the process."

b. she apparently told the Best Interests Assessor in April 2020 that she took the decision to relocate "to plan for her retirement" [C19]

c. in an e-mail to the Second Respondent on 6th July 2020 [D296], she says she "moved me and [AB] to the UK last November to escape US annihilation of [AB]'s care and services. [AB]'s federal benefits were confiscated, and our apartment home was set to market rent. Our utilities supplier was told to charge us separately in a building where utilities were included on one meter. Housing had also become an issue because of open drug use and fumes. Being born in the UK, my use of US government benefits became more despised…"

d. in the Care Act Assessment of 30th July 2020 it is recorded [D129] that M "informs the AAD team that she and [AB] left the USA due to [T's] abuse of them both."

e. at the beginning of her oral evidence, I asked M some open questions to help her put her account before the court. She explained that her understanding of the Letters of Guardianship is that they permit her "to orchestrate [AB]'s care in every regard." She told the Court that it "was obvious that Monroe was planning to move against Guardianship but they did not serve me with any papers so I wasn't aware of any plan when I brought [AB] here. It's not something I currently need to deal with because they should have done it earlier, they lost that opportunity."

f. when cross-examined, M described "having some issues with [AB]'s care – getting carers, formula, just challenges of living…the ongoing frustrations of not being able to get care regularly without fighting for it… Last November [things were] so far out of normal I found it difficult to cope. I started talking more to my family. I considered moving back to England where I have family who could help, to normalise… I was facing ongoing situations, starting to push, saying 'you need to take me to a judge.' They confiscated [AB]'s benefits and sent me a letter saying if I objected I could go to court. Then my benefits were taken away too, and they put our rent to market price. I didn't see how I could fight them in court and still live… so my family bought us tickets." M subsequently clarified that "they" referred to the Department of Social Services, whose conduct she regarded as "pure harassment."

J. Recognition of the Letters of Guardianship

K. The standard authorisation and the s21A challenge

L. Conclusions and Further steps

HHJ Hilder

23rd September 2020

Note 1 CCH Status Table at https://www.hcch.net/en/instruments/conventions/status-table/?cid=71. For some time there was uncertainty about this but the definitive position was spelled out by Sir James Munby P in Re O (Court of Protection: Jurisdiction) [2014] Fam 197 at 9.

[Back] Note 2 See the decision of Moylan J in An English Local Authority v. SW [2014] EWCOP 43.

[Back] Note 3 The London Borough of Hillingdon v. JV, RV & PY [2019] EWCOP 61 at paragraph 64. [Back] Note 4 128: This Article …. sets out the principle that the measures taken in a Contracting State and declared enforceable in another “shall be enforced in the latter State as if they had been taken by the authorities of that State.” This is a sort of naturalisation of the measure in the Contracting State where it is to be enforced. The authorities of the requested State will thus be able to stay execution of a placement measure taken abroad in cases where they would have been authorised to do so for a measure taken in their own State….”

[Back] Note 5 See paragraph 116 of the Lagarde Report: “This paragraph sets out the principle of recognition by operation of law in each Contracting State of the measures taken in another Contracting State. Recognition has as its object the measure as it exists in the Contracting State where it has been taken… Recognition by operation of law means that it will not be necessary to resort to any proceedings in order to obtain such recognition, so long as the person who is relying on the measure does not take any step towards enforcement. It is the party against whom the measure is invoked, for example in the course of a legal proceedings, who must allege a ground for non-recognition….” [Back]