Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

England and Wales Court of Appeal (Civil Division) Decisions

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> England and Wales Court of Appeal (Civil Division) Decisions >> Safestand Ltd v Weston Homes PLC & Ors [2025] EWCA Civ 374 (02 April 2025)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWCA/Civ/2025/374.html

Cite as: [2025] EWCA Civ 374

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

Neutral Citation Number: [2025] EWCA Civ 374

Case No: CA-2024-000760

IN THE COURT OF APPEAL (CIVIL DIVISION)

ON APPEAL FROM THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE, BUSINESS AND PROPERTY COURTS OF ENGLAND AND WALES, INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY LIST (ChD), PATENTS COURT

His Honour Judge Hacon sitting as a High Court Judge

Royal Courts of Justice

Strand, London, WC2A 2LL

Date: 2 April 2025

Before :

LADY JUSTICE ASPLIN

LORD JUSTICE ARNOLD

and

LADY JUSTICE ELISABETH LAING

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Between :

|

|

SAFESTAND LIMITED |

Claimant/ Appellant |

|

|

- and - |

|

|

|

(1) WESTON HOMES PLC (2) WESTON (LOGISTICS) LIMITED (3) WESTON GROUP LIMITED |

Defendants/ Respondents |

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Andrew Lykiardopoulos KC and Henry Edwards (instructed by DLA Piper UK LLP) for the Appellant

The Respondents did not appear and were not represented.

Oliver Morris of the United Kingdom Intellectual Property Office filed written submissions on behalf of the Comptroller-General of Patents, Trade Marks and Designs

Hearing date: 11 March 2025

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Approved Judgment

This judgment was handed down remotely at 10.30am on 2 April 2025 by circulation to the parties or their representatives by e-mail and by release to the National Archives.

.............................

Lord Justice Arnold:

Introduction

1. This is an appeal by the Claimant (“Safestand”) against paragraphs 2 and 16 of an order made by HHJ Hacon sitting as a High Court Judge on 13 March 2024 declaring invalid and revoking United Kingdom Registered Designs Nos. 90002293490001 (“RRD 0001”), 90003121450004 (“RRD 0004”) and 90003121450005 (“RRD 0005”) (collectively, “the Re-Registered Designs”) for the reasons given in his judgment dated 19 December 2023 [2023] EWHC 3250 (Pat).

2. The judge’s order was made following the trial of claims by Safestand against the Defendants (“Weston”) for infringement of three patents and of the Re-Registered Designs. Safestand’s claims for patent infringement succeeded, while the claims for infringement of the Re-Registered Designs failed. Falk LJ granted Weston permission to appeal against the findings of patent infringement and granted Safestand permission to cross-appeal against the findings that the Re-Registered Designs were invalid. A week before the hearing of the appeals, the parties were able to settle their dispute. Safestand nevertheless wishes to challenge the judge’s decisions that the Re-Registered Designs are invalid.

3. Safestand’s solicitors duly wrote to the Comptroller-General of Patents, Trade Marks and Designs as required by Practice Direction 52D paragraph 14.1(3) inviting him to assist the Court in accordance with the procedure established in Halliburton Energy Services Inc’s Patent [2006] EWCA Civ 185, [2006] RPC 26. Unfortunately this letter, and a follow-up letter, did not reach the relevant person in time before the hearing. After the hearing, we wrote to the Comptroller to request his assistance by way of written submissions. The Comptroller responded to that request, and we are grateful for the assistance provided to the Court. Safestand was given the opportunity, which it took, of filing written submissions in reply.

Builders’ trestles

4. Builders’ trestles are self-supporting low-level scaffolding structures incorporating horizontal platforms which are used for the construction and maintenance of buildings, particularly brick-laying and painting. They differ from other types of scaffolding in that they usually have either triangular or rectangular feet which enable frames to stand upright. At least two frames are required to support a platform, but there may be more. It is common for the feet to be detachable from the frames for transport and storage. A common hazard is that the board(s) forming the platform can flip up if a weight (such as the weight of a person) is placed on one end, and it is desirable to prevent this. It is common for the platform to be surrounded by vertical kickboards extending longitudinally and/or transversely. Such kickboards will need to be held in place in some manner.

The Re-Registered Designs

5. The Re-Registered Designs derive from corresponding Community Registered Designs registered with effect from 22 September 2004, 20 March 2005 and 20 March 2005 respectively. It is not necessary to discuss the legislative provisions which achieved this as a result of Brexit. The Re-Registered Designs are all registered in respect of “trestles for building industry”. RRD 0001 is also registered in respect of “scaffoldings and their components”. The judge reproduced the images in each of the Re-Registered Designs in a schedule to his judgment. I have followed his example, but it should be explained that the images available for inspection via the United Kingdom Intellectual Property Office website are clearer.

The grounds of invalidity

6. As the judge explained at [179], Weston challenged the validity of each of the Re-Registered Designs on three grounds: (i) it did not depict the design of a single product; (ii) it lacked clarity; and (iii) it lacked individual character. As the judge noted at [253], the third ground was pleaded only in the alternative to the first two grounds.

The legislative framework

7. The Registered Designs Act 1949 has been much amended, in particular to implement European Parliament and Council Directive 98/71/EC of 13 October 1998 on the legal protection of designs (“the Designs Directive”). The Designs Directive harmonised the designs legislation of the Member States of the European Union. Parallel provisions concerning Community (i.e. EU) Designs were contained in Council Regulation 6/2002/EC of 12 December 2001 on Community designs (“the CD Regulation”). The Designs Directive and the CD Regulation were interpreted in a number of decisions of the Court of Justice of the European Union and the General Court prior to 31 December 2021. This is assimilated law.

8. Section 1 of the 1949 Act provides:

“(1) A design may, subject to the following provisions of this Act, be registered under this Act on the making of an application for registration.

(2) In this Act ‘design’ means the appearance of the whole or a part of a product resulting from the features of, in particular, the lines, contours, colours, shape, texture or materials of the product or its ornamentation.

(3) In this Act—

‘complex product’ means a product which is composed of at least two replaceable component parts permitting disassembly and reassembly of the product; and

‘product’ means any industrial or handicraft item other than a computer program; and, in particular, includes packaging, get-up, graphic symbols, typographic type-faces and parts intended to be assembled into a complex product.”

9. Section 11ZA provides:

“(1) The registration of a design may be declared invalid—

(a) on the ground that it does not fulfil the requirements of section 1(2) of this Act;

(b) on the ground that it does not fulfil the requirements of sections 1B to 1D of this Act; or

(c) where any ground of refusal mentioned in Schedule A1 to this Act applies.

(1A) The registration of a design (‘the later design’) may be declared invalid if it is not new or does not have individual character when compared to a design which—

(a) has been made available to the public on or after the relevant date; but

(b) is protected as from a date prior to the relevant date by virtue of registration under this Act or an application for such registration.

(1B) In subsection (1A) ‘the relevant date’ means the date on which the application for the registration of the later design was made or is treated by virtue of section 3B(2), (3) or (5) or 14(2) of this Act as having been made.

(2) The registration of a design may be declared invalid on the ground of the registered proprietor not being the proprietor of the design and the proprietor of the design objecting.

(3) The registration of a design involving the use of an earlier distinctive sign may be declared invalid on the ground of an objection by the holder of rights to the sign which include the right to prohibit in the United Kingdom such use of the sign.

(4) The registration of a design constituting an unauthorised use of a work protected by the law of copyright in the United Kingdom may be declared invalid on the ground of an objection by the owner of the copyright.

(5) In this section and sections 11ZB, 11ZC and 11ZE of this Act (other than section 11ZE(1)) references to the registration of a design include references to the former registration of a design; and these sections shall apply, with necessary modifications, in relation to such former registrations.”

Interpretation of a registered design

10. The validity and the scope of protection of a registered design depend on the proper interpretation of the registration, and in particular of the images included in that registration: see Magmatic Ltd v PMS International Group plc [2016] UKSC 12, [2016] Bus LR 371 at [30] (Lord Neuberger of Abbotsbury). The design must be interpreted objectively. The circumstances pertaining to the conduct of the proprietor of the design, and by extension the intention of the designer, are not relevant: see Case C-488/10 Celaya Emparanza y Galdos Internacional SA v Proyectos Integrales de Balizamiento SL [EU:C:2012:88] at [55].

12. In Marks and Spencer plc v Aldi Stores Ltd [2023] EWHC 178 (IPEC) HHJ Hacon stated at [13]:

“Objective interpretation of a design is a matter for the court - not the court viewing the matter through the eyes of the informed user, particularly since there is no reason to suppose that the notional informed user is aware of the conventional understanding of what dotted lines, grayscale etc. are intended to convey, see Sealed Air Ltd v Sharp Interpack Ltd [2013] EWPCC 23, at [20]-[21].”

13. This statement of the law was not called into question on the appeal in that case [2024] EWCA Civ 178. It has the support of Stone, European Union Design Law (2nd ed) at 9.18-9.23.

14. In the present case the judge said:

“187. … Although in Marks and Spencer I stated the principle that the objective interpretation of a design as registered is a matter solely for court, I will own up to doubt about the breadth of that view of the law having dealt with this case. The interpretation of any of the conventions used in design registrations, dotted lines, greyscale and so on are for the court’s own assessment. However, I would have found these RRDs even more hard to interpret than I did without assistance from [Safestand’s expert witness Timothy] Mr Lohmann.

188. No doubt there may be other examples of where the informed user knows more than the court about how to interpret images in a registered design. I have in mind, obviously, only circumstances in which the informed user has specialised knowledge which is relevant to a significant aspect of the interpretation. In such a case interpretation of the images might usefully be done at least in part by the court through the eyes of the informed user. The practical consequence to litigation would be that sometimes there may be expert evidence about this. In an appropriate case such evidence, kept to the minimum necessary, is in my view admissible.

189. I think that Mr Lohmann’s evidence demonstrates that this is an appropriate case and I will consider his comments on the interrelationship between the articles shown in the images in the RRDs.”

15. I have no doubt that expert evidence is admissible in an appropriate case to educate the court as to the relevant design field, but I am doubtful whether expert evidence is admissible to interpret the images in a registered design. It is not necessary to resolve this issue for the purposes of the present appeal for the reason which follows.

16. The judge followed his statement in Marks and Spencer at [14] that “[p]roducts manufactured by the proprietor which are said to be protected by the registered design are irrelevant to interpretation of the design”. As this Court has subsequently held on the appeal in that case at [17], this is not correct. Thus, even if Mr Lohmann’s evidence is not admissible to interpret the Re-Registered Designs, it is permissible for the Court to have regard to Safestand’s trestles at least for the purpose of confirming conclusions drawn from the images.

The requirement that the design be of a single product

17. Safestand does not dispute that it follows from the definition in section 1(2) of the 1949 Act, which corresponds to Article 3(a) of the CD Regulation, that a registered design must be for a single product for the reasons lucidly explained by the judge at [190]-[198] and [201]-[207]. A complex product as defined in section 1(3) of the 1949 Act is a single product. Furthermore, a set of articles, such as a chess board and chess pieces or a canteen of cutlery, may also constitute a single product. (The difference between a complex product and a set of articles is that the former, but not the latter, is mechanically connected.) By contrast, different embodiments of the same design concept do not. As Safestand accepts, a registered design which does not comply with this requirement is invalid.

18. The leading case on this requirement is Case T-9/15 Ball Beverage Packaging Europe Ltd v European Union Intellectual Property Office [EU:T:2017:386], which concerned a design for beverage cans. The design was represented like this:

19. The European Union Intellectual Property Office Board of Appeal found that the design was not a design for a single product, but rather a design for three different sizes of can, and was therefore not registerable. (The solution to this problem would have been to file three different applications for registration.) The General Court upheld that finding:

“[60] As the Board of Appeal correctly notes in [18] of the contested decision, the subject matter of a design may only be a unitary object, since art.3(a) of Regulation 6/2002 refers expressly to the appearance of ‘a product’. Moreover, the Board of Appeal correctly stated, in [18] of the contested decision, that a group of articles may constitute ‘a product’ within the meaning of the abovementioned provision if they are linked by aesthetic and functional complementarity and are usually marketed as a unitary product.

[61] Proceeding from that premiss, which is not contested by the parties, the Board of Appeal concluded, in [19] of the contested decision, that the contested design did not satisfy the three conditions set out in [60] above and that, consequently, it could not be perceived as a unitary object. According to the Board of Appeal, when groups of beverage cans are offered, they always consist of cans of the same size, which is understandable, inter alia, in the light of transport and storage.

[62] The Board of Appeal’s conclusion relating, in the present case, to the lack of a unitary object is also not vitiated by error. Irrespective of the way beverage cans are marketed, it is clear that the three cans represented in the contested design do not perform a common function in the sense of a function which cannot be performed by each of them individually as is the case, for example, of table cutlery or a chess board and chess pieces …”

20. Thus the test is whether the articles are linked by aesthetic and functional complementarity and are usually marketed as a unitary product.

21. The final point to note is that the design of a single product may include items whose use is optional: see Case T-357/12 Sachi Premium-Outdoor Furniture Lda v Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) [EU:T:2014:55] at [37]-[38] (cushion for an armchair). An example closer to the present case might be the attachments for use with a vacuum cleaner.

Modular products

22. As the Comptroller accepts, it is possible to register a design for a modular product provided that it is a design of a single product. A modular product is a type of complex product consisting of a series of standardised parts or units from which the complex product is assembled.

Partial views and views of the whole product

23. As the judge noted at [199], the EUIPO’s Design Guidelines state at paragraph 5.3.4:

“A partial view is a view showing part of a product in isolation. A partial view can be magnified.

Partial views must be combined with at least one view of the assembled product (the different parts need to be connected to each other).”

24. The Comptroller has drawn the Court’s attention to the following paragraphs in the UKIPO’s Registered Designs Examination Practice Guide:

“11.31 Exploded views

An ‘exploded view’ consists of a representation showing a product with its parts disassembled, and is normally submitted in order to better illustrate how multiple parts fit together in order to form a single article. …. exploded views must always be accompanied by a representation showing the assembled product. The following example shows an acceptable ‘assembled’ view of a rollerball deodorant alongside a separate representation of an exploded view of that product. This view shows the constituent parts of the deodorant packaging being the lid, the roller ball, the cup that holds the roller ball and the container for the deodorant itself:

11.32 Partial views (or ‘fragmentary’ views)

A ‘partial view’ is a view showing part of a product in isolation which can, if required, be magnified. As with exploded views, partial views must be combined with at least one view representing the whole product. This can also apply to component parts of complex products, where there must be at least one view representing the product assembled (that is the different components need to be shown connected to each other). The following shows an acceptable representation consisting of three partial views together with an assembled view.

”

”

25. The Comptroller submits that, where a design consists of a product made up of a number of components, the application must include a representation of the design fully assembled with all features visible. This submission goes further than paragraph 11.32 of the Guide, and seems to me to be inconsistent with paragraph 11.31. As can be seen from the illustration below that paragraph, which is expressly stated to be acceptable, the assembled view of the deodorant does not show all of the components visible in the exploded view.

26. In any event, as Safestand points out, neither the Guidelines nor the Guide have the force of law. Safestands submits that it is sufficient that, considered together, the views depict the design of a single product. I accept this submission, but I should make it clear that I am not questioning the need for a view of the assembled product.

27. In a decision since the judge’s judgment which is of persuasive authority, Case T-25/23 Orgatex GmbH & Co KG v European Union Intellectual Property Office [EU:T:2024], the General Court explained that, in order for the views to depict the design of a single product, the views must be consistent with each other:

“38. Since the representation of a design for which registration is sought must enable that design, which is the subject of the protection sought by that application, to be clearly identified …, it is necessary, in particular, to examine whether the views constituting the representation as a whole show the appearance of a single or unitary product, that is to say, whether there is unicity of design.

39. In that regard, the requirement that the views be consistent implies that all the views show the appearance of one and the same product (or part of a product), so that they enable one and the same design to be clearly identified. Inconsistencies or contradictions between the filed views may lead to the conclusion that the representation shows different products, and therefore more than one design. The views relate to more than one design in particular when they constitute different embodiments or versions of the same concept, or when the use of the lines intended to identify the design or the use of the disclaimers of certain features is not consistent throughout the views.

40. There can be no unicity of design if the views constituting the representation as a whole are insolubly inconsistent or insurmountably contradictory, so that the appearance of a single product cannot be determined and, consequently, the representation does not allow a single design to be clearly identified. Conversely, the unicity of the design may be established despite minor discrepancies between the views, strictly to the extent that those views can nevertheless be reconciled in the sense of a unitary design. That being the case, the adjudicating bodies of EUIPO are not obliged to consider all possible combinations between the views provided by the applicant at the time of the application, but only those combinations which seem logical and plausible in the light of common experience.

41. A design which does not constitute a unitary object does not meet the definition laid down in Article 3(a) of Regulation No 6/2002 and must therefore be refused registration pursuant to Article 47(1) of that regulation …, or declared invalid if the ground for invalidity set out in Article 25(1)(a) of that regulation has been properly invoked (see, to that effect, … Ball Beverage Packaging Europe v EUIPO …, paragraphs 57 and 60).”

Colours

28. It can be seen from the images reproduced in the schedule to this judgment that they each depict components coloured variously red, yellow, green and blue. For reasons that will appear, I suspect that Safestand’s intention was that the colours would represent a code as to the different types of components included in the designs, but that mistakes were made in the colouring of some components. Be that as it may, Safestand accepts that, where a design is shown in colours (rather than in black and white), the colours are part of the design: see Magmatic v PMS at [33]-[34]. As the Comptroller points out, it follows that differently coloured versions of the same product constitute different designs.

Is lack of clarity a ground of invalidity?

29. Article 36 of the CD Regulation provides, so far as relevant:

“1. An application for a registered Community design shall contain:

...

(c) a representation of the design suitable for reproduction. However, if the object of the application is a two-dimensional design and the application contains a request for publication in accordance with Article 50, the representation of the design may be replaced by a specimen.”

30. The Court of Justice has interpreted Article 36(1)(c) as meaning that the design must be clearly identifiable: see Case C-217/17 P Mast-Jägermeister SE v European Union Intellectual Property Office [EU:C:2018:534] at [49].

31. Safestand contends that the requirement of clarity only applies to an application to register a design, and that lack of clarity is not a ground on which a registered design could subsequently be declared invalid: see section 11ZA quoted above. This is the rule which applies to patent claims: see Articles 84, 100 and 138 of the European Patent Convention, sections 14(5)(b) and 72(1) of the Patents Act 1977 and Terrell on the Law of Patents (20th ed) at 10-26. It is also the rule which applies to specifications of goods and services in trade mark registrations: see Case C-371/18 Sky plc v SkyKick UK Ltd [EU:C:2020:45].

32. The judge did not, at least in terms, reject Safestand’s contention. Rather, he said:

“216. It may be that a registered design with illustrations which do not make it possible to identify the features of the design with reasonable certainty is not a registration for a ‘design’ within the meaning of s.1(2). See also paragraph 46 of Mast-Jägermeister ….

217. However, it is enough for me to note that the judgment of the General Court in Ball Europe was based on art.3(a) of the Design Regulation, the equivalent of s.1(2) of the 1949 Act. It was not in dispute in these proceedings that the resolution of whether a design is of a single article is relevant to validity after registration. It seems to me that if it not possible to tell with reasonable certainty from the illustrations whether the design is of a single article, which implies being able to tell what that single design is, the registration is invalid.”

33. The Comptroller acknowledges that the grounds of invalidity identified in section 11ZA of the 1949 Act do not expressly include lack of clarity. The Comptroller nevertheless submits that lack of clarity should be considered to amount to a failure to comply with section 1(2), and hence a ground of invalidity pursuant to section 11ZA(1)(a), because clarity is just as important after registration as before. In support of this the Comptroller draws attention to the reasons for the requirement of clarity given by the Court of Justice in Mast-Jägermeister:

“53. In that regard, it should be noted that the entry of a design in a public register has the aim of making it accessible to the competent authorities and the public, particularly to economic operators. On the one hand, the competent authorities must know with clarity and precision the nature of the constituent elements of a design in order to be able to fulfil their obligations in relation to the prior examination of applications for registration and to the publication and maintenance of an appropriate and precise register of designs (see, by analogy, judgments of 12 December 2002, Sieckmann, C‑273/00, EU:C:2002:748, paragraphs 49 and 50, and of 19 June 2012, Chartered Institute of Patent Attorneys, C‑307/10, EU:C:2012:361, paragraph 47).

54. On the other hand, economic operators must be able to acquaint themselves, with clarity and precision, with registrations or applications for registration made by their current or potential competitors and thus to obtain relevant information about the rights of third parties (see, by analogy, judgments of 12 December 2002, Sieckmann, C‑273/00, EU:C:2002:748, paragraph 51, and of 19 June 2012, Chartered Institute of Patent Attorneys, C‑307/10, EU:C:2012:361, paragraph 48). Such a requirement, as the General Court points out, in essence, in paragraph 47 of the judgment under appeal, is intended to ensure legal certainty for third parties.”

34. In my view it is well arguable that Safestand is right that lack of clarity is not a ground of invalidity on the basis that the grounds listed in section 11ZA are exclusive and they do not include lack of clarity. The policy reasons prayed in aid by the Comptroller are equally applicable in the context of patents and trade marks, yet lack of clarity is not a ground of invalidity in those contexts. As Safestand points out, the difference between the two scenarios is that, prior to registration, any clarity issue can be remedied, if necessary, by filing new or amended representations, without the need for a further application and potentially only a small delay in the filing date: see Mast-Jägermeister at [15]-[17]. After registration, this is no longer possible.

35. This is an important issue which should only be decided if it is necessary to do so and with the benefit of full adversarial argument. Given that, for reasons which will appear, it is not necessary to decide this issue in the present case, I will assume for the purposes of this appeal that lack of clarity is a ground of invalidity.

The judge’s conclusions

36. The judge held that each of the Re-Registered Designs was invalid on the ground that it did not depict the design of a single product. In the alternative, he held that in each case it was not possible to tell with reasonable certainty that it was a single design. Having found at least Weston’s first ground established, the third did not arise for consideration.

Safestand’s grounds of appeal

37. Safestand appeals on two grounds. Ground one is that the judge was wrong to hold that each of the Re-Registered Designs were not for a single product. Ground two is that the judge was wrong to hold, to the extent that he did, that they lacked clarity.

Ground one: are the Re-Registered Designs for single products?

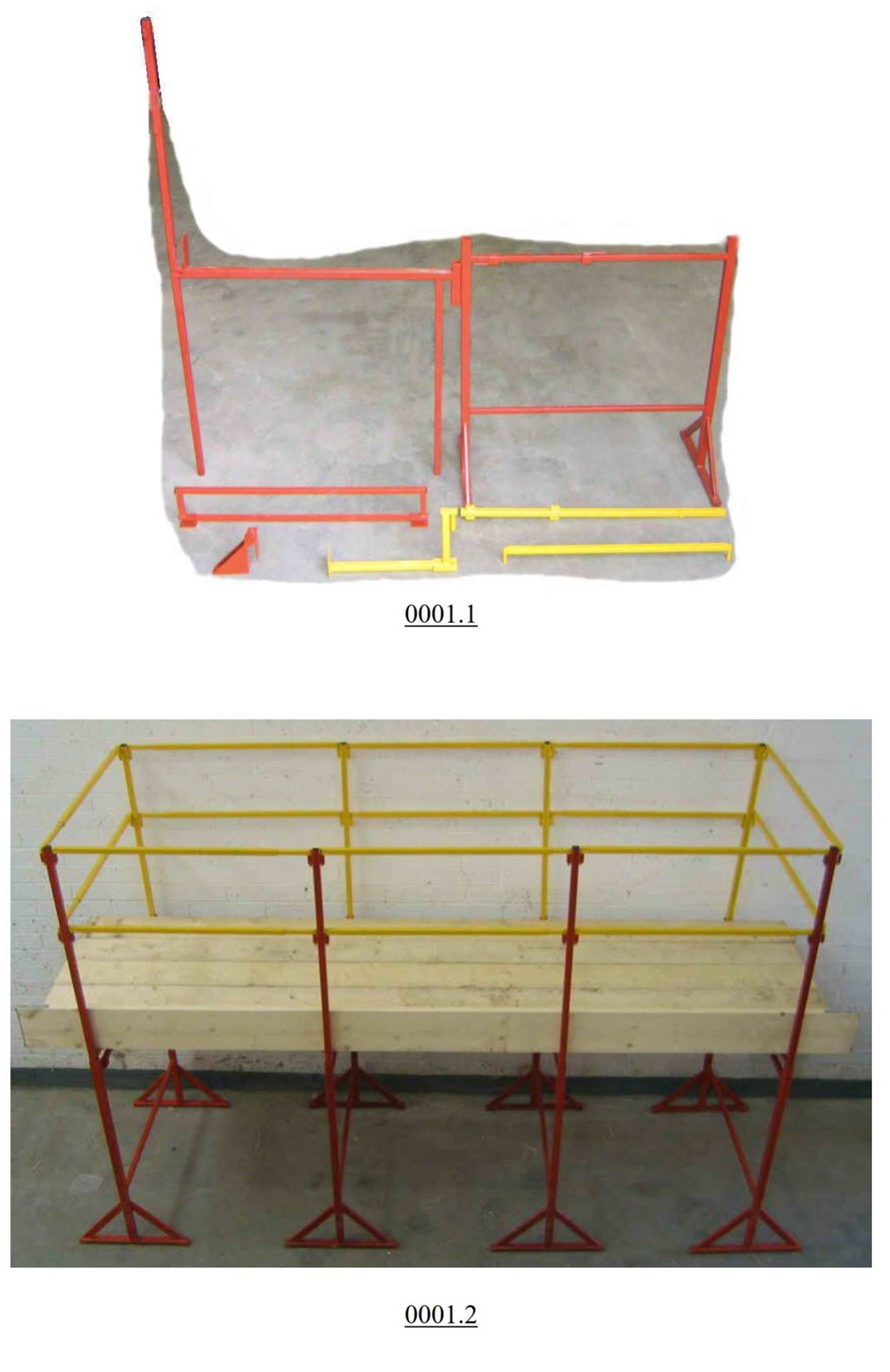

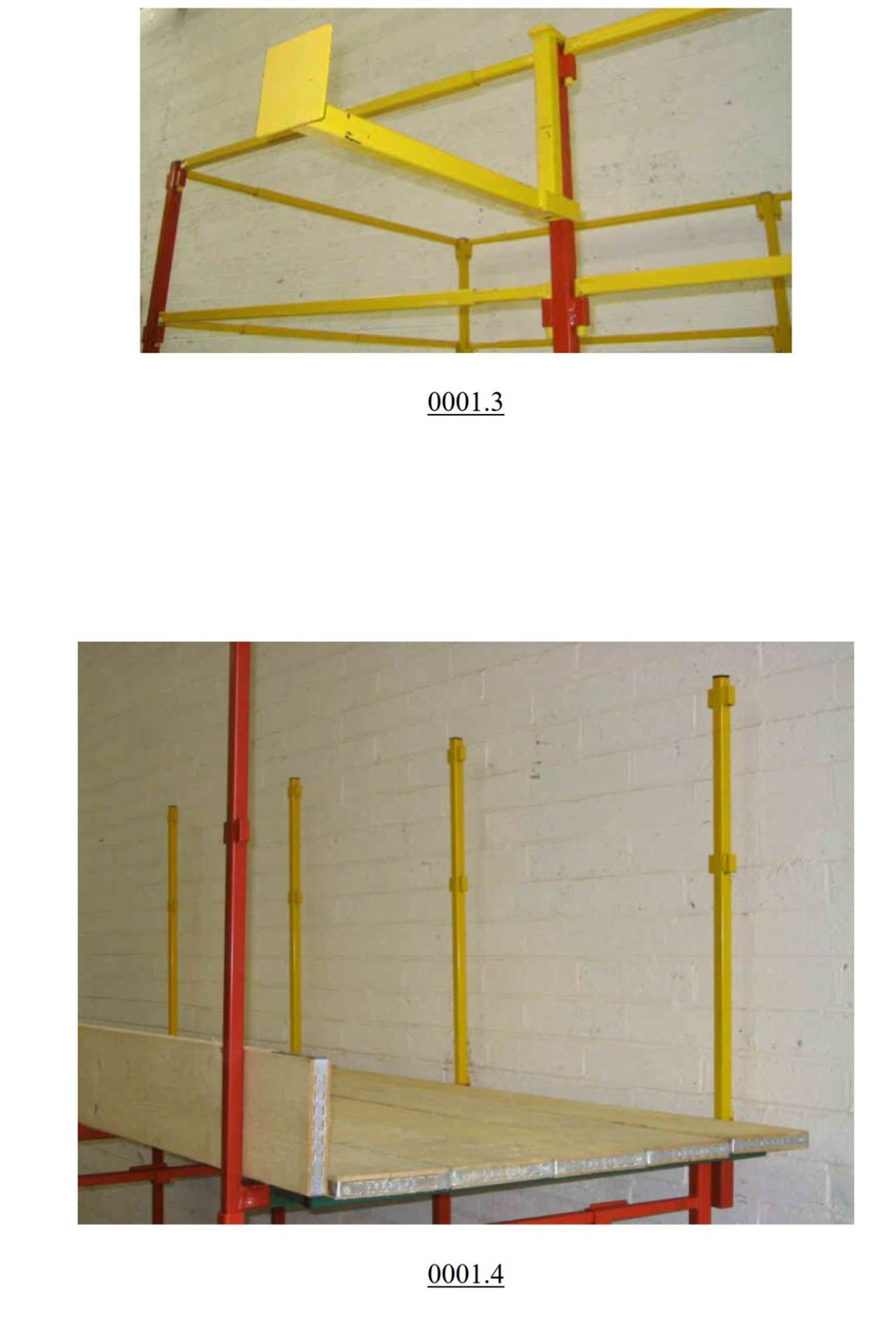

38. The judge began his consideration of this issue by noting at [221]:

“ Neither Safestand nor Weston submitted that any of the RRDs in suit is a design of a set of articles …. Most of the images presented are views of part of a complex product, the trestle, but there were no submissions about that. I can approach all three RRDs on the basis that the design claimed is of a single article, a trestle. In each case there is at least one view of the assembled trestle plus views of a part or parts of the trestle.”

RRD 0001

39. As the judge noted, image 0001.2 is of the complete assembly and the other images show parts of it. His analysis was as follows:

“225. Image 0001.1 shows a red h frame on the left without feet and with no lower crossbar, and a red rectangular frame on the right with feet and a lower crossbar. Mr Lohmann said that the left hand component slots into that on the right to make a completed h frame as shown in image 0001.5. I would not have known this without Mr Lohmann’s evidence but I will assume that it is correct.

226. Mr Lohmann confirmed what I had guessed in relation to the two straight yellow bars in image 0001.1. The upper one is a vertical bar which fits into a slot in the right hand red frame, see image 0001.4. The lower one is a horizontal bar or handrail in the completed trestle.

227. The yellow L shaped item, as Weston describe it, at the bottom of 0001.1 seems to be the ladder holder extension of image 0001.3. But it is not shown in image 0001.2 where one would expect it to be visible, implying that the design has alternative embodiments, with or without the ladder holder. Mr Lohmann confirmed this.

228. The red anti-flip bracket in image 0001.1 is not visible in 0001.2 but that could be because it is hidden by the platform. Images 0001.4 and 0001.5 suggest that it is part of the overall design but can be either red or green. It could of course be red at one end and green at the other, there is no way of telling.

229. Image 0001.4 has no hand rails but this may just imply that they are removeable.

230. There is no sign of any kickboard brackets in image 0001.2. They appear in 0001.6 and 0001.7 in alternative colours of red and green.

231. My ambiguities in RRD 0001 may be summarised as follows:

(1) The anti-flip bracket may be red or green in alternative embodiments.

(2) The ladder holder extension is either present or absent in alternative embodiments.

(3) Kickboard brackets may be optional and even if they are not, they may be red or green in alternative embodiments.

232. For the foregoing reasons, the design which RRD 0001 seeks to protect is the design of a builders’ trestle in several alternative embodiments. I think that Safestand in its written argument was seeking to suggest that if alternative colours are shown in a registered design, that just means that the design claimed has contrasting colours. There is a difference between a single design with contrasting but unspecified colours … and a design shown in colour with alternative colours. That latter is not a single design but several alternatives, albeit each having the same shape. …

233. The design represented in the images of RRD 0001 is not a single design. If I had not arrived at a clear conclusion about that, I would have decided that is not possible to tell with reasonable certainty that it is a single design. On either ground RRD 0001 is not validly registered.”

40. Safestand contends that the judge made a number of errors in this analysis and reached the wrong conclusion. It is convenient before turning to the errors which the judge is said to have made to set out how Safestand contends that the images should be interpreted.

41. The starting point is that, according to Safestand, it is clear from the images that they depict a modular design enabling builders’ trestles of varying sizes to be assembled from seven types of components. Furthermore, the design incorporates both integral uprights and removable uprights and horizontal safety rails.

42. These seven types of components are shown in image 0001.1. They are as follows:

i) Two red frames that form the structure of a trestle on which boards can be rested, having a single integral upright on one side. To the right of the image is the base (with triangular feet) and to the left is the upper portion which slots into the base to form the “h” frame of the trestle.

ii) Two straight yellow components which are examples of a removable upright and a horizontal rail.

iii) A yellow “L” shaped ladder bracket on which a ladder can be rested.

iv) A red rectangular “anti-flip” bracket (used under the ends of the boards to stop them flipping up).

v) A red kickboard bracket (to hold transverse kickboards).

43. The other images then depict how these components are used in the design to assemble the product. Image 0001.2 shows the assembled product with one kickboard and without the ladder bracket. In this image the colours assist in interpretation by differentiating the integral red uprights from the removable yellow uprights and horizontal safety rails. An important point which is apparent from comparing image 0001.2 with image 0001.1 is that the assembled product incorporates multiple individual components. Four “h” frames have been assembled from four of each of the two red frame components. There are also four yellow uprights and 16 yellow horizontal safety rails. The anti-flip bracket and kickboard bracket are not shown in image 0001.2.

44. Image 0001.3 shows how the ladder bracket is attached to the assembled trestle.

45. Image 0001.4 shows one red integral and four yellow removable uprights without any horizontal rails. Under the ends of the boards a green component can be seen. Image 0001.5 makes it clear that this is the anti-flip bracket. Although it is green in this image, it is plainly the rectangular component depicted in red in image 0001.1.

46. Image 0001.5 also shows more clearly a feature of the upper red frame component which is visible in image 0001.1, namely a leaf which extends upwards from the horizontal bar adjacent to the upright. If these images are compared with images 0001.2 and 0001.4, it can be deduced that these leaves hold the longitudinal kickboard visible in the latter.

47. Image 0001.6 shows how the kickboard bracket shown in image 0001.1 is used to hold a transverse kickboard perpendicular to a longitudinal one which the bracket hooks over. Image 0001.7 shows the same design of bracket, but this time in green.

48. Safestand accepts that the net effect of the images is that the product includes at least one red and one green anti-flip bracket and at least one red and one green kickboard bracket.

49. Safestand contends that inspection of its product confirms the interpretation of the images set out above.

50. Turning to the judge’s reasoning, Safestand’s overarching submission is that the judge failed to recognise that the test laid down in Ball Beverage, and further explained in Orgatex, is satisfied. Contrary to the view apparently taken by the judge, there is nothing “insolubly inconsistent or insurmountably contradictory” in the images. More specifically, concerning the points identified by the judge at [231]:

i) The judge was wrong to think that the anti-flip bracket may be red or green in alternative embodiments. As explained above, there is at least one red bracket and at least one green one.

ii) The judge was wrong to the think that the fact that the ladder bracket may be present or absent means that there are alternative embodiments. It is a single product which includes a part whose use is optional.

iii) The same two points apply to the kickboard bracket.

51. I accept these submissions. It is telling that there is no reference in the judge’s judgment to the modular quality of the design. In my judgment the images in RRD 0001 depict a single modular product with the attributes I have discussed. This is confirmed by inspection of Safestand’s product, photographs of which are in evidence.

52. In my view the only possible reason for doubting the validity of the design is that, although there is at least one red anti-flip bracket and at least one green one and there is at least one red kickboard bracket and at least one green one, the design embraces, say, two red anti-flip brackets and two green ones, or even one red anti-flip bracket and two green ones or vice-versa, and the same goes for the kickboard brackets. Given the modular nature of the product, however, I do not consider that these possibilities constitute different products. I would point out that there is no difference in this respect between the brackets on the one hand and the frames, uprights and rails on the other hand. Although image 0001.2 shows four red frames, four yellow uprights and 16 rails, it is evident that the design also embraces, say, three red frames, three yellow uprights and 12 yellow rails or five red frames, five yellow uprights and 20 yellow rails. Although the judge did not expressly say so, it appears that he did not consider that this prevented the design from being the design of a single product, and I think that he was correct not to do so.

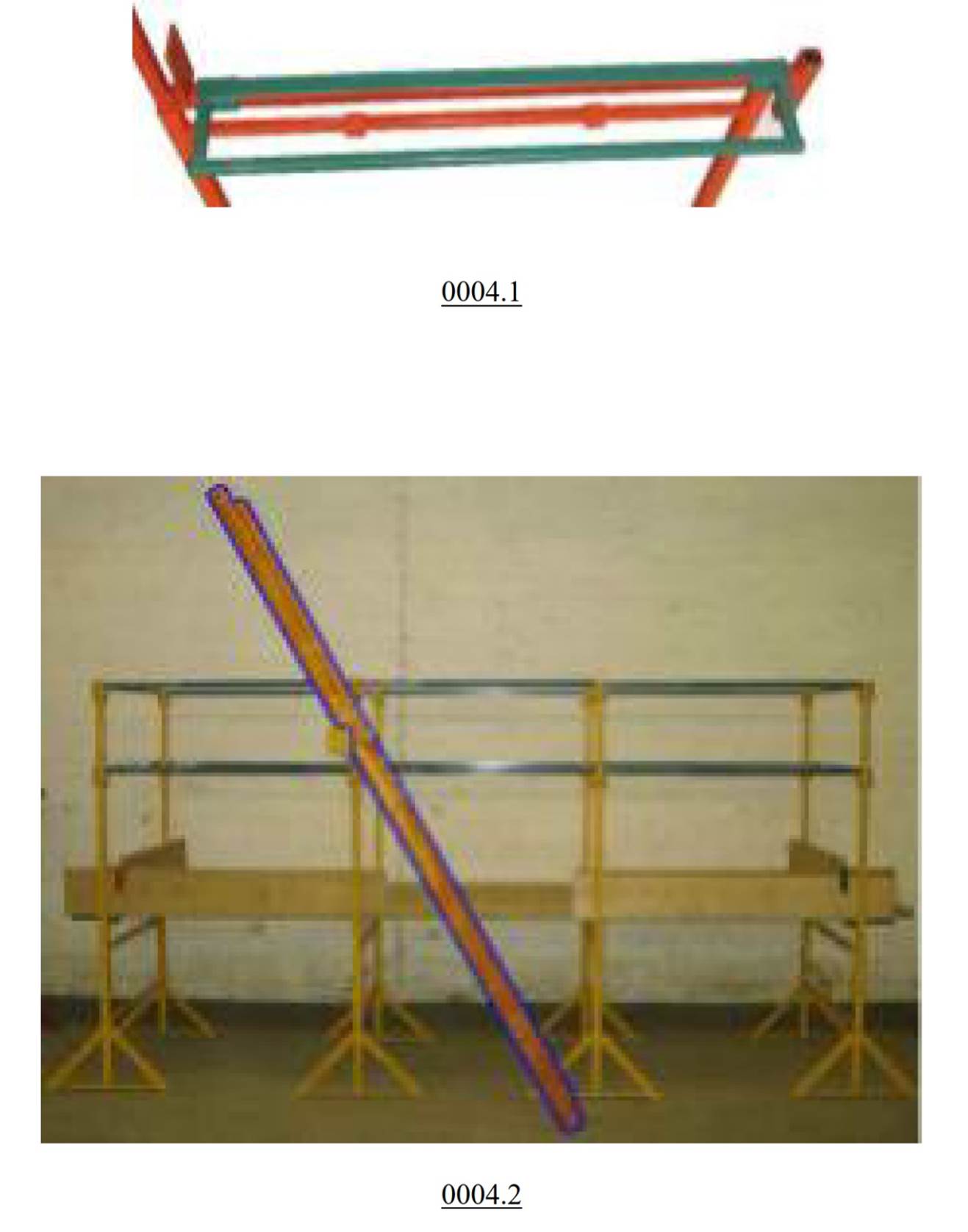

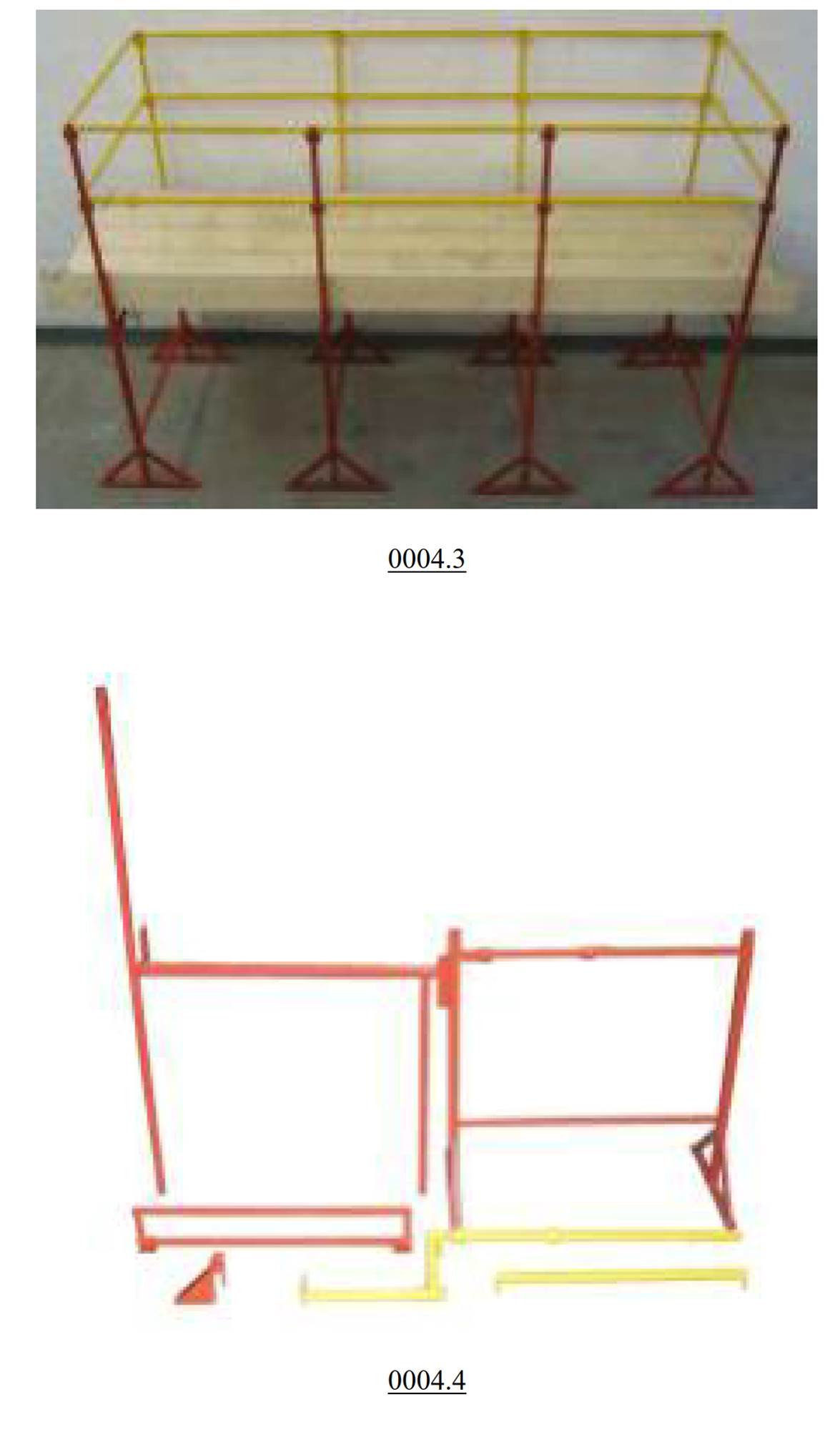

RRD 0004

53. Again image 0004.2 shows the complete assembly (with a ladder which does not form part of the design, as indicated by the purple line drawn round it), while the other images show the parts of it. Although the judge did not comment on this aspect, RRD 0004 differs from RRD 0001 in that image 0004.5 shows two details of the horizontal rails not visible in RRD 0001. These show that the rails are telescopic with a push-pin system (visible when extended at top, but not when retracted at bottom) and a spigot for fastening to an upright (bottom).

54. The judge’s analysis was at [234] as follows:

“All [three] difficulties relating to RRD 0001 apply to RRD 0004. In addition:

(4) The h frames may be coloured yellow or red.

(5) The handrails may be coloured yellow or blue.”

55. Safestand repeats its submissions concerning RRD 0001 so far as the first three difficulties are concerned. So far as points (4) and (5) are concerned, Safestand again accepts that the fact that different colours of frames and handrails are shown in the images means that both colours are present in the product. It does not mean that there are alternative embodiments for the reasons given above. I agree with this.

RRD 0005

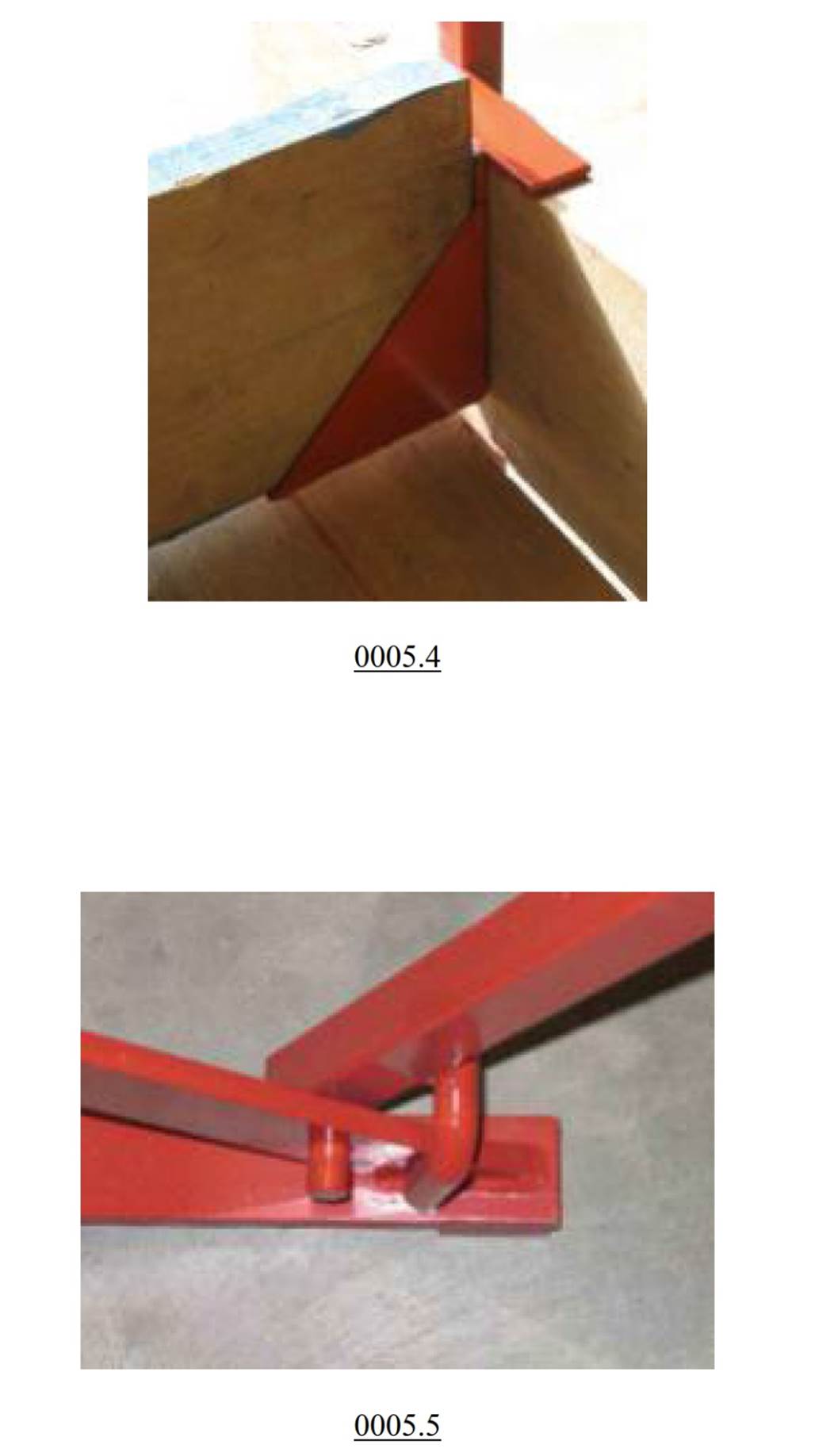

56. This time image 0005.6 shows the complete assembly (with a ladder which does not form part of the design, as indicated by the purple line drawn round it), while the other images show the parts of it. RRD 0005 differs from RRD 0001 and RRD 0004 in that it includes an eighth type of component visible at the extreme left in image 0005.7. This is a cross-brace. The use of four such cross-braces is shown in image 0005.6. The way in which the cross-brace connects to an upright is shown in image 0005.2 and the way in which it connects to a foot of a frame is shown in image 0005.5. In addition, the lower part of the h frame includes two bracing struts as can be seen from both image 0005.7 and image 0005.6. Finally, this is a taller design, as can be seen from image 0005.6, which explains the inclusion of bracing.

57. The judge’s analysis at [235] was as follows:

“(1) The anti-flip bracket may optionally be red (image 0005.6) or green (image 0005.1).

(2) I found it difficult to know whether the parts shown in images 0005.2 and 0005.5 fit into the whole as shown in image 0005.6 or whether they are parts of an embodiment alternative to that shown in image 0005.6. Mr Lohmann said that they depict the way in which the cross-brace is attached to the system.

(3) Image 0005.7 has an h frame without feet or lower cross bar. Although Mr Lohmann did not say so, I would infer from he said about RRD 0001 that it is slotted into the frame with legs.

(4) One might expect the red kickboard bracket of image 0005.4 to be visible in the image of the assembly, 0005.6. It is not, which may imply that the kickboard bracket is optional.”

58. Safestand contends that point (1) is a mistake on the part of the judge and the anti-flip bracket is only shown in green (images 0005.1 and 0005.7). Although the judge considered that image 0005.6 shows red anti-flip brackets, Safestand contends that the image is not clear enough to draw that conclusion. My impression, having viewed the image online where it can be magnified, is the same as that of the judge. In the alternative, Safestand submits that this is a minor discrepancy of the kind permitted in Orgatex at [40]. I accept that submission. Although both anti-flip brackets appear to be red in image 0005.6, it is not much of a stretch to suppose that one is intended to be red and the other green. That would not mean that the images showed more than one product for the reasons given above. Furthermore, even if image 0005.6 is interpreted as showing two red anti-flip brackets, the net effect of the images is that RRD 0005 comprises at least two red and one green anti-flip brackets.

59. So far as point (2) is concerned, Safestand contends that it can be deduced that images 0005.2 and 0005.5 show how the cross-braces attach, and this is confirmed by inspection of the Safestand product. I accept this.

60. As for point (3), Safestand says that this is no different to RRD 0001: it is simply that the upper frame component is positioned differently in image 0005.7 compared to image 0001.1. Again, I accept this.

61. Finally, Safestand again says that point (4) is mistaken: the hooks on the backs of two red kickboard brackets (visible on the example in image 0005.7) are in fact visible poking over the longitudinal kickboard in image 0005.6. I accept this.

Conclusion

62. In my judgment Safestand is correct that each of the Re-Registered Designs shows the design of a single modular product, and therefore they are not invalid on this ground.

Ground two: lack of clarity

63. It can be seen from the judge’s reasoning that, to the extent that he held that the Re-Registered Designs were lacking in clarity, it was because it was not reasonably clear that they were each for a single product. Even assuming lack of clarity is a ground of invalidity, Safestand submits that the Re-Registered Designs are not unclear for the reasons explained above. I accept this.

Disposition

64. For the reasons given above I would allow the appeal.

Lady Justice Elisabeth Laing:

65. I agree.

Lady Justice Asplin:

66. I also agree.

Schedule

Images in RRD 0001

Images in RRD 0004

Images in RRD 0005