Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

England and Wales Court of Appeal (Civil Division) Decisions

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> England and Wales Court of Appeal (Civil Division) Decisions >> Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd & Anor v Astellas Pharma Inc [2023] EWCA Civ 880 (25 July 2023)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWCA/Civ/2023/880.html

Cite as: [2023] EWCA Civ 880

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

ON APPEAL FROM THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE, BUSINESS AND PROPERTY COURTS OF ENGLAND AND WALES, INTELLLECTUAL PROPERTY LIST (ChD), PATENTS COURT

Mr Justice Meade

Strand, London, WC2A 2LL |

||

B e f o r e :

LORD JUSTICE STUART-SMITH

and

LADY JUSTICE FALK

____________________

| (1) TEVA PHARMACEUTICAL INDUSTRIES LIMITED (2) TEVA UK LIMITED |

Appellants |

|

| - and - |

||

| ASTELLAS PHARMA INC |

Respondent |

|

And Between : |

||

| (1) SANDOZ AG (2) SANDOZ LIMITED |

Appellants |

|

| - and - |

||

| ASTELLAS PHARMA INC |

Respondent |

____________________

Piers Acland KC and Anna Edwards-Stuart (instructed by Hogan Lovells International LLP) for the Respondent

Hearing dates : 17-18 July 2023

____________________

Crown Copyright ©

- This is an appeal from an order of Meade J dated 24 June 2022 dismissing the Appellants' claim for revocation of European Patent (UK) No 1 559 427 ("the Patent"), and in consequence Supplementary Protection Certificate No. SPC/GB13/035, and granting the Respondent relief for infringement, for the reasons given in the judge's judgment dated 1 June 2022 [2022] EWHC 1316 (Pat). The Patent claims mirabegron, or a salt thereof, for use in the treatment of overactive bladder ("OAB"). Mirabegron is a ß3 adrenoreceptor ("ß3-AR") agonist. There is no challenge to the claimed priority date of 7 November 2002. The Appellants contend that the claimed invention was obvious over Australian Patent Application AU 199889288 ("288").

- The judge found that the Patent was addressed to a skilled team consisting of a clinician and a pharmacologist working on new or improved treatments for OAB.

- The Appellants' experts were Prof Paul Abrams (clinician) and Dr Thomas Argentieri (pharmacologist). The Respondent's experts were Dr Ian Mills (clinician) and Dr Gordon McMurray (pharmacologist). As the judge explained, Prof Abrams' role in the case was fairly limited. The judge's assessment of the other witnesses concluded at [25]:

- The parties provided the judge with a statement of agreed common general knowledge. The judge reproduced most of it at [50]-[87]. The key points are as follows.

- The lower urinary tract in humans consists of the urinary bladder and the urethra. The bladder is a hollow, muscular organ which stores urine and is divided into its two main parts: the body and the base. Urine enters the bladder from the kidneys via the ureters. The bladder body is mainly comprised of a muscular wall with smooth muscle cells, referred to as the detrusor muscle, which is by far the largest part of the bladder. The bladder base consists of the trigone and the bladder neck, which leads to the urethra in the wall of which the urethral sphincter is embedded.

- The smooth muscle in the detrusor is structurally and functionally different from the muscles found in the bladder base, the urethra and the pelvic floor. Within the wall of the urethra, just above the pelvic floor, is the intraurethral (also termed intramural) striated muscle sphincter which prevents urine leakage during filling and relaxes to allow the bladder to empty.

- The urethra is the conduit through which urine flows during voiding. It passes through the pelvic floor muscles and comprises both striated and smooth muscles. Together, the striated muscle and smooth muscle form the urethral sphincter mechanism, whose contraction during urine storage causes increased resistance in the urethra which prevents urine leakage.

- The main functions of the bladder are to store urine as it flows from the kidneys into the bladder during the "storage phase" and to rapidly empty the urine during the act of urination, also known as micturition or voiding, which is referred to as the "voiding phase".

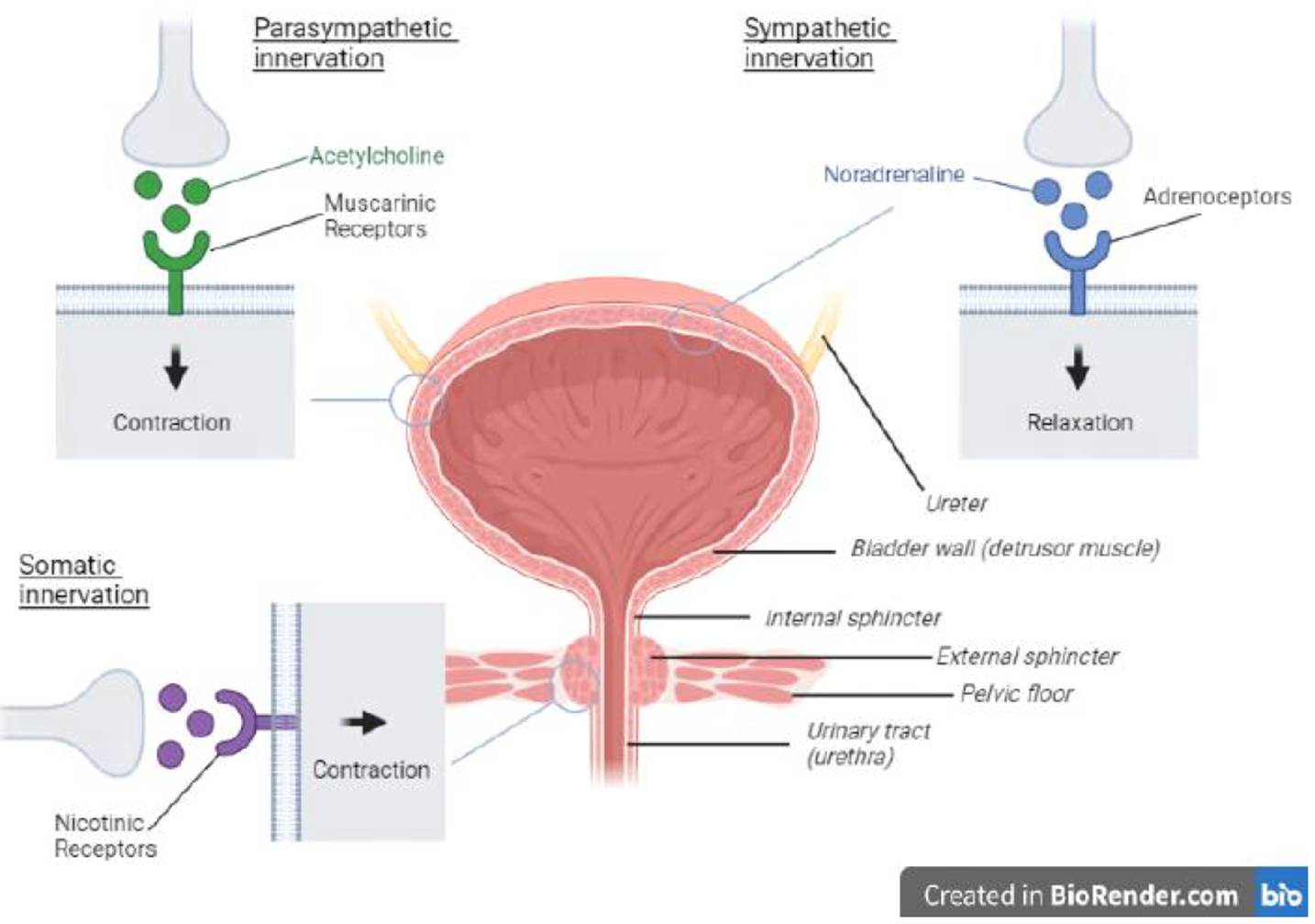

- The interactions of the anatomical features of the lower urinary tract and the human nervous system comprise a tightly-controlled feedback loop mechanism involving the brain, the spinal cord, peripheral nerves and the lower urinary tract. The lower urinary tract is innervated by peripheral nerves of the parasympathetic and sympathetic branches of the autonomic nervous system ("ANS"), and by the somatic nervous system.

- The ANS is a division of the peripheral nervous system. It acts mostly unconsciously and regulates bodily functions such as breathing, digestion and urination. The parasympathetic and sympathetic branches of the ANS essentially act in opposition to one another. Put simply, the sympathetic nervous system is active during the storage phase and the parasympathetic nervous system is active during the voiding phase.

- The somatic nervous system is associated with the voluntary control of movement through skeletal muscle, as well as involuntary control via reflexes. The somatic nerves innervate the striated muscles of the pelvic floor and the urethral sphincter and are active during bladder filling to maintain continence.

- The autonomic and somatic nervous systems exert their control through chemical messengers known as neurotransmitters. The relevant neurotransmitters are acetylcholine ("ACh") and noradrenaline.

- During the storage phase, there are no signals from the parasympathetic nervous system to the detrusor, and therefore no contraction occurs. Activation of the sympathetic nerves triggers the release of noradrenaline which binds to adrenoceptors causing the detrusor to relax. Noradrenaline is also released in the smooth muscle of the urethral sphincter where it binds to a1 adrenoceptors, causing contraction. The somatic nerves innervating the striated muscles of the pelvic floor and the urethra release ACh triggering them to remain tightened and closed. In this manner pressure in the bladder remains low whilst pressure in the urethra remains high, allowing urine storage.

- In the voiding phase the somatic nerves are inhibited, as is the sympathetic outflow to the bladder base and the urethral smooth muscle, to allow relaxation of the bladder outlet and pelvic floor. The parasympathetic nerves that supply the detrusor release ACh, which stimulates muscarinic receptors leading to detrusor contraction. Thus pressure in the bladder increases whilst the pressure in the urethra is reduced, allowing urine to flow out of the bladder.

- This is shown in schematic form in the diagram below (omitting sympathetic nervous system innervation of the smooth muscle of the urethral sphincter).

- OAB is a set of symptoms which are presumed (in the absence of indication to the contrary) to be caused by involuntary detrusor contractions that occur during the storage phase. The symptoms associated with OAB include urgency (having to rush to the toilet suddenly), frequency (having to urinate too often during the day), nocturia (getting up at night to urinate) and urge incontinence (associated with urgency).

- In November 2002 antimuscarinics were the frontline pharmaceutical treatment for OAB. They work by blocking muscarinic receptors, preventing binding of acetylcholine to the receptors and therefore impeding detrusor contraction. It was well known that the existing antimuscarinic compounds had significant side-effects caused by "off-target" responses at receptors elsewhere in the body, the most common and troublesome being dry mouth. It was also known that antimuscarinics can interfere with proper bladder emptying.

- As a result of these well-known problems with antimuscarinics, there was a strong interest in the development of new drugs for treating OAB.

- Methods of pre-clinical research into new therapies included both in vitro and in vivo tests.

- A common in vitro test was the organ bath method. Strips of detrusor muscle (derived from a variety of different animal species or from humans) are dissected, suspended under tension in an organ bath and perfused with physiological saline. Carrying out this process in the absence and then in the presence of a potential agent may be useful in demonstrating that the agent prevents the contraction of the bladder or causes relaxation. In comparison to live models, a bladder strip assay has the limitation of being outside of the influence of the rest of the body (e.g., the effects of the nervous system).

- Common in vivo tests comprised both physiological and pathological animal models.

- In November 2002 it was known that the ß adrenoceptor family included ß1 and ß2 adrenoceptors. It had recently been determined that "atypical" adrenoceptors reported in earlier research were in fact a third sub-class, ß3 adrenoceptors. ß1 adrenoceptors were known to be located predominantly on cardiac muscle, mediating increased heart rate and force of contraction. ß2 adrenoceptors were known to be located predominantly on smooth muscles mediating relaxation, especially in blood vessels where they mediated vasodilatation, in the lung where they mediated bronchodilatation, and in the uterus where they mediated uterine relaxation. ß2 adrenoceptor activation was also known to elicit tremors in humans due to activity at the level of skeletal muscle.

- It was thought that the main ß adrenoceptor found in the human detrusor was the ß3 adrenoceptor. ß3 adrenoceptors were also known to be present in fat cells. ß3 adrenoceptor agonists were the subject of some human and animal in vitro and animal in vivo research in relation to their effect on detrusor function.

- The following matters regarding ß3 adrenoceptors were known:

- The judge made findings as to three areas of disputed common general knowledge at [88]-[125]. Only two of these are significant for present purposes.

- The position that had been reached by November 2002 was summarised in Yamaguchi, "ß3-Aadrenoreceptors in Human Detrusor Muscle", Urology, 59 (Supplement 5A), 25-29, 2002, which was agreed to be common general knowledge. The judge cited extensively from Yamaguchi at [92]-[94]. The judge's key findings based on Yamaguchi and the expert evidence were as follows:

- There is a point about Dr McMurray's work at Pfizer which the judge referred to in [101] (and again in [199], quoted below) that it is convenient to deal with here. As counsel for the Appellants pointed out, Dr McMurray was careful to make it clear that the work he was describing took place after the priority date of the Patent. As counsel for the Respondent demonstrated, however, Dr McMurray gave much the same answer when asked about the position by reference to the common general knowledge in 2002 in a passage quoted by the judge at [181]. Furthermore, when asked whether he was surprised by what he found when working at Pfizer, Dr McMurray's answer was no, a passage quoted by the judge at [183].

- The expert evidence demonstrated that a number of other therapeutic approaches to the treatment of OAB were being investigated in November 2002. The judge's overall finding based on this evidence at [125] was as follows:

- After some basic explanation at [0002]-[0003] about the shortcomings of existing treatments for OAB and the rising numbers of sufferers, the specification notes at [0004] that in International Patent Application WO 99/20607 ("607") mirabegron was reported to be useful for promoting insulin secretion, enhancing insulin sensitivity, and for anti-obesity and anti-hyperlipemic activity. It points out, however, that the application did not disclose or suggest use of mirabegron for treating OAB.

- At [0005] the specification refers to another patent application, WO/98/07445, which is said to be relevant to bladder conditions, and which mentions the compound CGP-12,177A. As will appear below, this compound is used as a comparator in the experimental work in the Patent; it is a partial ß3 adrenoreceptor agonist.

- At [0013]-[0017] the specification explains that the inventors have found that mirabegron is useful as a remedy particularly for use in the treatment of OAB. Details are given as to the chemical form of the compound (free or as a salt) in [0020], methods of administration in [0021] and its synthesis at [0022]-[0026].

- From [0027] to [0042] three experimental examples are described. It is common ground that each of the methods used in the examples was a conventional one.

- Example 1 is carried out in an in vitro model using strips of rat detrusor muscle which are made to contract by the application of carbachol (a muscarinic receptor agonist used to test the ability of a compound to counteract contraction caused by the natural agonist of the receptors which drive contraction in vivo) and of potassium chloride (which does not relate to the normal in vivo pathway, so that the ability to counteract this form of contraction helps demonstrate that the test compound is not working through the muscarinic pathway and would be more likely to be able to relax detrusor muscle regardless of the cause of the contraction). The relaxant effect of mirabegron is assessed and compared with that of CGP-12,177A. Mirabegron is seen to achieve much greater relaxation and at lower concentrations. By one measure mirabegron was 270-fold more potent, and by another 383-fold more potent, than CGP-12,177A.

- Example 2 is an in vivo model in rats. Rhythmic bladder contraction was experimentally induced in anesthetised animals and frequency and pressure of contractions was measured for different concentrations of mirabegron. Vehicle was used as a control. Dose dependent reduction in contraction frequency was seen for mirabegron but not for the control. It is said that the inventors believe that this shows clinical utility for OAB. Contraction pressure was not affected until the highest dose was given, and the specification explains that that would be preferred because it indicates that urine retention is not induced.

- Example 3 is also an in vivo rat experiment. OAB was chemically induced and saline injected into the bladder to induce a micturition reflex. The average interval for urination was measured before and after administration of mirabegron and was longer after administration. The specification again says that the inventors believe that this indicates clinical efficacy for overactive bladder.

- The specification summarises the results and the implications for utility at [0042]:

- As the judge pointed out at [137], all this work was done in rat-based models; there is no work relating to humans. There is also no test of whether mirabegron is selective for ß3 in preference to ß1 or ß2.

- 288 derives from 607. It was published on 6 May 1999, and claims a priority date of 17 October 1997. The applicant was a predecessor to the Respondent.

- The title of 288 is "Amide derivatives or salts thereof". The abstract states that "an amide derivative" according to a Markush formula is disclosed. It goes on:

- Under the heading "Technical Field", 288 states that the invention relates to novel amide derivatives or salts thereof and to therapeutic agents for diabetes mellitus.

- Under the heading "Background Art", the first three paragraphs discuss diabetes and its therapy in general terms. 288 continues on pages 2 to 3:

- Having referred to a prior application, 288 states there is still a demand for new therapeutic agents for diabetes.

- Under the heading "Disclosure of the Invention", 288 begins on page 4 by saying:

- This is followed by a statement of the invention which is in similar terms to the abstract save that it refers to the claimed amide derivatives "having anti-obesity and anti-hyperlipemia actions due to a selective stimulating action to ß3-receptors".

- There is then a long section disclosing methods of synthesising compounds within the claimed Markush formula which goes on until page 15.

- Under the heading "Industrial Applicability", 288 states at pages 15 to 16:

- The judge commented on this passage at [148]:

- On page 17, 288 suggests that the claimed amide derivatives are useful to prevent or treat various other conditions in addition to diabetes:

- 288 then moves on to experimental work. At page 18, it says:

- Two points should be noted about this paragraph. First, the reference to "ß3-receptor stimulation" is an obvious typo and should just be to "ß-receptor". Secondly, and more importantly, the expression "the compound of the present invention", which is used here and elsewhere in the document, appears at first blush to mean any compound falling within the Markush formula. As the skilled reader would appreciate, however, it is very unlikely that the authors have tested all such compounds. It is therefore unclear which compound or compounds the authors are referring to at this stage.

- Three different experiments are then described. Each experiment uses a standard method. The first is a hypoglycemic test in mice. The details do not matter. The result is reported on page 19:

- These are the only concrete, numerical data in 288. They concern Example 6, which is not mirabegron.

- The second experiment is another animal test, this time in rats. Again the details do not matter, but what was observed was an increase in insulin levels and an inhibition of blood sugar increase in animals receiving "the compound of the present invention". This time, no numerical data are given.

- The third experiment uses two different cell lines expressing human ß-receptors. Again, the details do not matter. What was tested for was the stimulating effect on cAMP production. The authors says at the foot of page 20 that "[i]ntensity of action of each compound was compared …", so in this instance it appears that more than one compound was tested. Nevertheless, no numerical data are reported. Over on page 21 the authors baldly assert that "[i]t has been ascertained that the compound of the present invention has a selective stimulating action to human ß3-receptor".

- Under the heading "Best Modes for Conducting the Invention", six examples of compounds with some details of their synthesis are given. This section begins on page 23:

- The structural formulae for the six Examples are given in Table 1. Example 5 is mirabegron. Example 6 is the one for which numerical data are given in the hypoglycemic mouse test mentioned above.

- Some of the six compounds are structurally similar to each other and some are not. Dr Argentieri accepted that Examples 1, 4 and 6 were similar one to another while 2, 3 and 5 stood out as different, and he accepted that even for the (relatively) similar ones it was not possible to infer from their structure that they would have the same activity.

- Before the judge the Appellants argued that 288 teaches that all six examples were tested for ß3 selectivity, while the Respondent argued that, apart from the test on Example 6 in the mouse hypoglycemia test, which was irrelevant to OAB, it was not clear which other tests were done on which, if any, compounds.

- The judge's assessment was as follows:

- There is no challenge by the Appellants to this assessment.

- The judge applied the structured approach to the assessment of obviousness set out in Pozzoli SpA v BDMO SA [2007] EWCA Civ 588, [2007] FSR 37. He identified the steps from 288 to the claim as being the choice of mirabegron and its use to treat OAB as opposed to the conditions mentioned in 288.

- The judge quoted the pithy summary of the Appellants' case set out in their skeleton argument:

- The judge analysed this case at [174] as involving the following elements:

- The judge summarised the Respondent's responses (omitting one point which the judge did not consider significant) at [177] as follows:

- Having set out and analysed the key passages of cross-examination relied upon by each side at [179]-[186], and having rejected the urine retention point relied upon by the Respondent at [187]-[191], the judge set out his assessment at [192]-[203].

- He repeated that he accepted that at the priority date the ß3-AR agonism mechanism had "momentum" relevant to OAB arising from the recent advancements in understanding that he had identified in relation to the common general knowledge, and hence ß3-AR agonists had, in a general sense, potential as agents to treat OAB. He went on at [194]:

- The Appellants' case overstated the skilled addressee's confidence for the following reasons:

- As to oversimplification:

- Accordingly, the judge concluded that the claimed invention was not obvious in the light of 288. The judge went on to reject an allegation of insufficiency which is no longer maintained, but it is pertinent to note what he said in this context at [205]:

- Obviousness involves a multi-factorial evaluation, and therefore this Court is not justified in intervening in the absence of an error of law or principle on the part of the judge: see Actavis Group PTC EHF v ICOS Corp [2019] UKSC 15, [2019] Bus LR 1318 at [78]-[81] (Lord Hodge). This accords with the general approach of this Court to appeals against evaluative decisions: see Re Sprintroom Ltd [2019] EWCA Civ 932, [2019] BCC 1031 at [72]-[78] (McCombe, Leggatt and Rose LJJ).

- In the present case the Appellants not only face this obstacle, which confronts all appeals on obviousness, but two more specific difficulties. The first is the judge's assessment of the expert witnesses, which the Appellants cannot and do not challenge. The second is that, on its face, the judgment contains a very careful, detailed and nuanced consideration of the evidence and the issues.

- The judge was persuaded to grant permission to appeal on the basis that there was arguably a tension between the House of Lords' decision in Conor Medsystems Inc v Angiotech Pharmaceuticals Inc [2008] UKHL 49, [2008] RPC 28 and this Court's decisions in Pozzoli and Koninklijke Philips NV v Asustek Computer Inc [2019] EWCA Civ 2230, [2020] RPC 1, the resolution of which could lead to a different view of what the technical contribution of the Patent was and a different assessment of obviousness. On the appeal, however, the Appellants accepted that there was no conflict between Conor on the one hand and Pozzoli and Philips on the other hand. Instead, the Appellants contend that the judge erred in principle because he did not correctly apply the law as stated in Pozzoli and Philips.

- In Pozzoli Jacob LJ said:

- In Philips Floyd LJ cited this passage and said at [73]:

- The Appellants argue that the judge's reasoning depends upon two uncertainties, neither of which is dispelled by the Patent: first, there was uncertainty as to ß3-AR agonist therapy as an approach for treating OAB pending human clinical trials; and secondly, there was uncertainty as to whether mirabegron was a human ß3 selective agonist, or at least a sufficiently potent one. These uncertainties are not dispelled by the Patent because all it presents is the results of experiments in rats. Not only are there no clinical results, but also there are no results of experiments on human tissue.

- Skilfully though this argument was developed by counsel for the Appellants, I do not accept it for two reasons.

- First, as counsel for the Respondent pointed out, the judge's reasoning was not that the claimed invention was prima facie obvious in the light of 288, but the skilled team would think that it would not work because of some technical prejudice or perceived problem. If that had been his reasoning, it would then have been necessary for the Respondent to show that that prejudice or problem was plausibly dispelled or solved by the Patent. The judge explicitly recognised this point in his judgment. After citing Philips, he said at [35]:

- Rather, the judge's reasoning was that it was not obvious in the light of 288 read with the common general knowledge to try mirabegron as a treatment for OAB with a reasonable expectation of success, in the first place by carrying out experiments in rats of the kind reported in Examples 1, 2 and 3 of the Patent. In summary, this was partly due to the skilled team's lack of confidence in ß3-AR agonism as a potential therapy for OAB and partly due to the poor quality of the disclosure in 288.

- Secondly, the Appellants' argument is in reality a more subtle variant of the argument rejected by the House of Lords in Conor. As Lord Hoffmann explained:

- The invention claimed in the Patent is a medical use: the use of mirabegron to treat OAB. It is an implicit requirement of the claim that mirabegron is efficacious for that purpose (although no particular level of efficacy is specified). The Appellants accept that the Patent makes it plausible that mirabegron is effective for the treatment of OAB. That being so, Conor makes it clear that the question of obviousness does not depend on the amount of evidence presented in the Patent to justify that conclusion. Thus the question is simply whether 288 read together with the common general knowledge made it obvious to try mirabegron as a treatment for OAB with a reasonable expectation of success. As discussed above, the judge held that the answer to that question was no, based upon findings as to common general knowledge and as to the disclosure of 288 and upon a careful assessment of the expert evidence, none of which are, or can be, challenged.

- Counsel for the Appellants also argued that the judge had failed to recognise that the Respondent was not entitled to the monopoly conferred by the Patent because the Patent had made no technical contribution to the art since it had neither identified a new human ß3-AR agonist (mirabegron having been disclosed as such in 288, even if without supportive data) nor identified a new use for ß3-AR agonists (their potential for the treatment of OAB being common general knowledge). Nor had the Patent dispelled the two uncertainties identified in paragraph 75 above. As counsel for the Respondent submitted, however, on the judge's findings the Patent did make a technical contribution to the art, as can be seen most clearly from what the judge said at [205]. The judge was fully entitled to reach that conclusion on the evidence.

- In short, there was no error in the judge's approach and no basis for this Court to interfere with his evaluation.

- For the reasons given above I would dismiss this appeal.

- I agree.

- I also agree.

Lord Justice Arnold:

Introduction

The skilled team

The expert witnesses

"Overall these points left me with the impression that Dr Argentieri was trying a little too hard to find points in favour of the Claimants. It was not enough to lead me to reject his evidence outright, and many of his points were well made and solidly supported, but I bear it in mind and I thought that Astellas' witnesses were overall more fair and balanced when it came to the issues on CGK and obviousness, and put themselves in the position of the ordinary uninventive addressees better than him."

Agreed common general knowledge

Bladder physiology

OAB

Treatment of OAB

Methods of investigating new therapies

ß3 adrenoreceptors

i) ß3 adrenoceptors had recently been identified to be present in the human detrusor muscle via mRNA expression studies and to be the predominant ß adrenoceptor in that tissue (but that ß1 and ß2 mRNA was also expressed);

ii) a number of ß3 adrenoceptor agonists which were thought to be selective were known, including BRL 37344, CL 316243, FK 175, CGP-12,177A and L-755,507 (which had been reported to have a >1000-fold greater selectivity for the ß3 receptor as compared to the ß1 receptor and no activity at the ß2 receptor);

iii) ß3 adrenoceptors were thought to be able to mediate relaxation of the detrusor based on experiments using isolated detrusor strips and selective ß3 agonists and antagonists. The tissues were either taken from lab animals or, where human tissue was used, from patients who had undergone a cystectomy (removal of the bladder) due to bladder cancer;

iv) in vivo studies in animals (including rats with a urinary frequency phenotype) had demonstrated the ability of some ß3 adrenoceptor agonists to increase bladder volume in a dose dependent manner, but also that relaxation of the detrusor of many species was thought to be mediated by ß2 adrenoceptors in addition to the putative role of the ß3 adrenoceptor;

v) ß3 adrenoceptors were known to be present in fat cells and the gastrointestinal tract (where they were thought to regulate motility), and ß3 adrenoceptor agonists had previously been tried as anti-obesity treatments in human clinical trials, based on demonstration of anti-obesity effects in animal models; but these studies were ultimately unsuccessful and revealed several issues impeding translation of the effects seen in pre-clinical experiments to clinical efficacy, including that:

vi) the agonists tested had side effects of tremor and tachycardia (probably due to effects on the ß1 and ß2 adrenoceptors);

vii) the rat and human ß3 adrenoceptors differ materially in their pharmacology such that agonists which were selective for the rat ß3 adrenoceptor were not full agonists of the human receptor.

Disputed common general knowledge

The ß3 adrenoreceptor in detrusor function and ß3 adrenoreceptor agonists

"96. One of the Claimants' points was that the idea of using ß3-AR agonists for treating OAB had 'momentum'. I agree with this. Significant results advancing the understanding of the role of ß3-ARs in the bladder had been achieved in a period of just a few years leading up to the priority date, and suggestions for therapeutic potential had been made swiftly thereafter. …

99. The increasing understanding of ß3-AR agonists in the context of the bladder must … be tempered by the CGK fact, set out in Yamaguchi, that ß3-AR agonists had failed in human clinicals trials as anti-obesity agents even after success in animals. One possible reason for this, explained in Yamaguchi, was that the ß3-AR agonists tested in the clinic were only weak, partial agonists of the human ß3-adrenoreceptor, and not selective for the human ß3-adrenoreceptor. More generally, there was a lack of full understanding of the reasons.

100. Overall, I think the CGK was that the lack of clinical trials of ß3-AR agonists for OAB was recognised as a gap in the knowledge of the art, that they would probably come soon, and that they had potential, but that their outcome was fairly uncertain.

101. It was also implicit in the Claimants' position that the skilled team would think that any ß3-AR agonist would work to relax detrusor tissue and therefore be likely to work as a therapy for OAB. I do not believe that that was the CGK. Dr McMurray disagreed with the Claimants' position, and said that it would be expected that not all ß3-AR agonists would behave the same, and I accept that evidence. He supported this with evidence, which I also accept, that at Pfizer it was found that some ß3-AR agonists which were potent in cell lines did not work well in detrusor muscle, and that predictability for agonists was always difficult and more complex than for antagonists. This work at Pfizer was not, of course, CGK, but it lends reality and support to Dr McMurray's evidence on this point.

102. Yamaguchi identifies the need to find better ß3-AR agonists. What it says about them has an emphasis on selectivity (and that the one that it used, L-755,507, was selective, though no information is given about potency) but clearly also refers to the need for agonists to be full, and potent. Dr McMurray gave an explanation, which I found convincing and accept, that the problem would have been seen to be that the compounds tried had been weak more than that they had been partial agonists. This was the context for a further debate about the CGK situation in relation to the existence of good human ß3-AR agonist compounds.

103. L-755,507 is mentioned in Yamaguchi …. Other than that there was no evidence that any particular individual ß3-AR agonist compound was CGK; the skilled team would think that if they needed one they would try to look up possibilities in the literature. Dr McMurray prepared a table of ß3-AR agonist compounds which he gleaned from the papers in the case, the prior art and papers cited in the priority document, the Patent and the prior art. There were a large number and many were both potent and selective. However, only three were shown to be promising ß3-AR agonists for the human ß3-AR, and one of them was L-755,507 itself.

104. The Claimants argued that no structure for L-755,507 was available (none is given in Yamaguchi); Dr McMurray said that he thought it was. I was not told what source Dr McMurray had in mind, but in view of his general care and reliability I think he is more likely than not to have been correct.

105. Of the other two compounds, one was in a paper by Ok et al., from Merck, and one was from Igawa's group, referenced in a paper put to Dr McMurray by Counsel for the Claimants, and for which no structure was given in the paper.

106. So the overall picture is that there were many ß3-AR agonists, but only a handful of human-selective, potent ones. Two were not CGK, and there was limited CGK information about L-755,507 as I have just explained.

107. The Claimants' case was that the state of the art in terms of CGK was that clinical trials for OAB were highly desirable and would have been imminent or already underway had it not been for the lack of human-selective, good ß3-AR agonist substances. I do not accept that this was the case; the Claimants did not show that the keenness for clinical trials was as strong as they said and they did not demonstrate that there was a general attitude in the field that the one thing holding back the start of clinical trials was the lack of appropriate compounds to test …"

Other therapeutic approaches

"… this was a field where there was known to be a real problem with the existing treatments, and in which there were a significant number of possibilities to be considered, none of which was the clear favourite, and none of which had an overwhelmingly clear rationale or body of evidence. The lack of a clear direction forward was, in a way, evidenced by the willingness in the field to press on with approaches like vanilloids with their obvious apparent challenges. This fits with my view that there was no established field of ß3-AR agonists and that drug companies in the field were typically trying multiple approaches. Some but not all of the active research programmes included ß3-AR agonists, and some who started work on ß3-AR agonists later gave up on it …"

The Patent

"Thus, the active ingredient of the present invention shows a strong bladder relaxation action in 'isolated rat bladder smooth muscle relaxation test', decreases the contraction frequency of rhythmic bladder contraction on a dose-depending manner in 'rat rhythmic bladder contraction measurement test' and prolongs the micturition interval in 'micturition function measurement test on cyclophosphamide-induced overactive bladder model rat' whereby it is clinically useful as a remedy for overactive bladder. In addition to overactive bladder as a result of benign prostatic hyperplasia, it is also able to be used as a remedy for overactive bladder accompanied with urinary urgency, urinary incontinence and pollakiuria."

288

"A therapeutic agent for diabetes mellitus having both an insulin secretion promoting action and an insulin sensitivity potentiating action and also having anti-obesity and anti-hyperlipemia actions due to a selective stimulating action to ß3-receptors, is also disclosed."

"U.S. Patents 4,396,627 and 4,478,849 describe phenyl-ethanolamine derivatives and disclose that those compounds are useful as drugs for obesity and for hyperglycemia. Action of those compounds is reported to be due to a stimulating action to ß3-receptors. Incidentally, it has been known that b-adrenaline receptors are classified into ß1, ß2 and ß3 subtypes, that stimulation of ß1-receptor causes an increase in heart rate, that stimulation of ß2-receptor stimulates decomposition of glycogen in muscles, whereby synthesis of glycogen is inhibited, causing an action such as muscular tremor, and that stimulation of ß3-receptor shows an anti-obesity and an anti-hyperglycemia action (such as decrease in triglyceride, decrease in cholesterol and increase in HDL-cholesterol).

Unfortunately, those ß3-agonists also have actions caused by stimulation of ß1- and ß2-receptors such as increase in heart rate and muscular tremor, and they have a problem in terms of side effects.

Recently, it was ascertained that ß-receptors have differences to species, and it has been reported that even compounds having been confirmed to have a ß3-receptor selectivity in rodential animals such as rats show an action due to stimulating action to ß1- and ß2-receptors in human being. In view of the above, investigations for compounds having a stimulating action which is selective to ß3-receptor in human being have been conducted recently using human cells or cells where human receptors are expressed."

"The present inventors have conducted an intensive investigation on compounds having both an insulin secretion promoting action and an insulin sensitivity potentiating action and found that novel amide derivatives show both a good insulin secretion promoting action and a good insulin sensitivity potentiating action and furthermore show a selective stimulating action to ß3-receptors, leading to accomplishment of the present invention."

"As confirmed by a glucose tolerance test and a hypoglycemic test in insulin-resisting model animals as described later, the compound of the present invention has both a good insulin secretion promoting action and a good insulin sensitivity potentiating action, so that its usefulness in diabetes mellitus is greatly expected. Although the ß3-receptor stimulating action may have a possibility of participating in expression of the insulin secretion promoting action and the insulin sensitivity potentiating action, other mechanism might also possibly participate therein, and the details thereof have been still unknown yet. The ß3-receptor stimulating action of the compound of the present invention is selective to ß3-receptors in human being. It has been known that the stimulation of ß3-receptor stimulates decomposition of fat (decomposition of the fat tissue triglyceride into glycerol and free fatty acid), whereby a disappearance of fat mass is promoted. Therefore, the compound of the present invention has an anti-obesity action and an anti-hyperlipemia action (such as triglyceride lowering action, cholesterol lowering action and HDT cholesterol increasing action) and is useful as a preventive and therapeutic agent for obesity and hyperlipemia (such as hypertriglyceridemia, hyper-cholesterolemia and hypo-HD-lipoproteinemia). Those diseases have been known as animus factors in diabetes mellitus, and amelioration of those diseases is useful for prevention and therapy of diabetes mellitus as well."

"`288 is expressing doubts even in relation to that which it specifically concerns, and it is not natural just to shrug them off when thinking of applying the teaching in a different setting."

"Further, the selective ß3-receptor stimulating action of the compound of the present invention is useful for prevention and therapy of several diseases which have been reported to be improved by the stimulation of ß3-receptor. Examples of those diseases are shown as follows.

It has been mentioned that the ß3-receptor mediates the motility of non-sphincteral smooth muscle contraction, and because it is believed that the selective ß3-receptor stimulating action assists the pharmacological control of intestinal motility without being accompanied by cardiovascular action, the compound of the present invention has a possibility of being useful in therapy of the diseases caused by abnormal intestinal motility such as various gastrointestinal diseases including irritable colon syndrome. It is also useful as the therapy for peptic ulcer, esophagitis, gastritis and duodenitis (including that induced by Helicobacter pylori), enterelcosis (such as inflammatory intestinal diseases, ulcerative colitis, clonal disease and proctitis)."

"The action of the compound of the present invention has been ascertained to be selective to ß3-receptors as a result of experiments using human cells, and the adverse action caused by other ß3-receptor stimulation is low or none."

"The compound of the present invention significantly lowered the blood sugar level as compared with that prior to the administration of a comparative drug in both cases of oral and subcutaneous administrations. For example, the compound of Example 6 showed a hypoglycemic rate of 48% in average by oral administration of 10 mg/kg. From this result, it is shown that the compound of the present invention has a good potentiating action to insulin sensitivity."

"The present invention is further illustrated by way of Examples as hereunder. Compounds of the present invention are not limited to those mentioned in the following Examples but covers all of the compounds represented by the above formula (I), salts thereof, hydrates thereof, geometric and optical isomers thereof and polymorphic forms thereof."

"167. … Leaving aside the semantic picking apart of 'the compound' and 'each compound', it is striking that in just one instance actual numerical data is given for a compound, Example 6, and even that not in the selectivity assay. Why would the authors include that and then be so vague about describing what they had done in the third, selectivity test, if they had in fact tested all six Examples with success? Why would they not include numerical data? My overall conclusion is that the skilled addressee would think that no safe conclusion could be reached over what testing had been done other than the one data point for Example 6. That does not mean that they would think the teaching could not usefully be progressed; they would have the hope that if they tested the six Examples they might get some positive results, but they would have no expectation for any particular compound, other perhaps than for Example 6 where it might be a bit more likely that selectivity had been tested, but from which no conclusion about other compounds could be drawn without testing.

168. The argument over which compounds were tested for selectivity rather overshadowed a related point which I think is of importance, which is that on any view there is no data about the affinity or potency of any of the compounds and no efficacy test of any relevance to OAB."

The judge's assessment of obviousness

"The Claimants' case is straightforward. They submit that by the priority date it was part of the common general knowledge that ß3-agonists had the potential to be used to treat OAB and that consequently it was obvious that compounds disclosed as ß3-adrenoceptor agonists were potential therapeutics. Mirabegron had been disclosed in the AU288 Application as a ß3-adrenoceptor agonist and it follows that no technical contribution resides in identifying that it has potential for use in treating OAB."

" i) It was CGK that selective ß3-AR agonists had the potential to treat OAB.

ii) There was a shortage of potent human, selective ß3-AR agonists.

iii) Therefore when in that context the skilled team saw some selective ß3-agonists in `288 they would be of interest.

iv) It would therefore be obvious to test the 6 compounds in `288 in a detrusor strip assay with the expectation that they would induce relaxation.

v) It would be obvious thereafter to take those that succeeded, or at least mirabegron, into clinical trials with a reasonable expectation of success."

"i) ß3-AR agonism was just one of a number of possible ways of treating OAB under consideration by the art.

ii) There was no clinical evidence yet that ß3-AR agonism would work to treat OAB.

iii) ß3-AR agonism had been unsuccessful in the obesity field.

iv) `288 is not about OAB at all and does not even mention it.

v) `288 gives no information about mirabegron's activity.

…

vii) If ß3-AR agonism were to be pursued there were many more attractive compounds to choose from than mirabegron.

viii) Although it accepted that it cannot rely on concerns over possible side effects in general because of the fact that the Patent contains no information about selectivity, there would have been a concern about urine retention, which would not be a side effect arising from lack of selectivity, but rather from ß3-AR agonism itself. That, Astellas says, is addressed by the Patent."

"However, the Claimants' case suffers from the two defects of overstating the confidence that that would give the skilled addressee, and of oversimplifying the situation, in particular to the effect that any ß3-AR agonist would be likely to succeed as a treatment. One can see these two problems clearly in the formulation of the Claimants' case that they put forward in their written opening and which I have quoted above."

i) "ß3-AR agonism … had not been used successfully for any drug for any condition, and it had failed for diabetes" ([195] referring back to [86(v), (vi)], [99]);

ii) "clinical evidence was what was missing and should be looked for, [but would not] necessarily fall into place … clinical trials would be an exercise in hoping to find something new and promising, not a routine matter with a strong or clear expectation of positive results" ([196] referring back to [100]);

iii) "the large number of possibilities in play to improve the existing treatments for OAB", with some companies exploring ß3-AR among other things but other companies not doing so ([197] referring back to [125]);

iv) overall "Dr Mills and Dr McMurray gave a much fairer impression of the state of play in seeking to improve OAB treatments than did Dr Argentieri: it was possible that ß3-AR agonists would work for OAB and it was possible that they would not. The same could be said for a number of the other mechanisms under consideration for OAB" ([198]).

"199 … the central problem facing the Claimants seemed to me to be the poor quality of the disclosure of `288 as it applied to mirabegron in particular and the Examples generally, with the very limited data given. It was because of that that the Claimants had to contend, effectively, that any selective ß3-AR agonist would be seen as obvious to use for the treatment of OAB. My findings on the evidence as set out above are that that is not so and was not the perception of the skilled addressee. It could not be assumed that any ß3-AR agonist would work and it could not be predicted that the results for one would necessarily apply to another. The Claimants put to Astellas' witnesses, and argued, that no ß3-AR agonist had ever failed to show activity in detrusor tissue, but I accept the answer given, that failures would not be published, and I have already said that Dr McMurray gave evidence that at Pfizer some agonists found to be potent in cell assays did not work in detrusor muscle.

200. This does not mean that the skilled addressee would positively think that mirabegron or the other Examples in `288 would not work, but it does mean that there would be a substantial degree of uncertainty. Furthermore, `288 does not 'show its working'; the choice of compounds and structures to explore and test is not explained. The reader would probably expect that the thinking was shaped by the application that the authors had in mind (diabetes), and I was not at all convinced by the Claimants' response to that, which was that it did not matter what condition the authors were working on, provided that they came up with ß3-AR agonists in the end.

201. The Claimants tried to bring some unity and reality to their arguments about ß3-AR agonism on the one hand and `288 on the other by the contention that the mechanism had been seen as extremely attractive for some time by the priority date, but was held up by the lack of appropriate compounds. Then, it was said, `288 would provide a good way forward for the first time. I have rejected this on the facts in dealing with the CGK. At least some other suitable compounds were around, and the skilled addressee would not think that there was a limitation such that they would naturally decide to proceed with the ill-characterised compounds in `288. … the argument was also unconvincing because Dr Argentieri had not with any clarity spelled it out in his written evidence, and I accept Astellas' contention that it only really surfaced in the Claimants' opening oral submissions.

202. It is of some relevance that `288 does not mention OAB in the list of possible conditions to be treated, but I do not think that it is a critical point in isolation, mainly because of my view that there is force in the Claimants' argument that the skilled addressee would think OAB's omission might be explained by `288 having been written before the advances I have identified above. ….

203. Finally, a point made by the Claimants was that the effort involved in making the six compounds exemplified in `288 would not be great. I accept that so far as it goes, …, but it is a small part of the picture and one still has to inquire which 6 compounds … to make, for what purpose and with what confidence that they might succeed."

"… the disclosure of the Patent is quite different from that of `288. It focuses in specifically on mirabegron, teaches its use in treating OAB, and gives specific, concrete results in identified assays, albeit not in humans or human tissue."

Appeals on obviousness

The appeal

"25. … There is an intellectual oddity about anti-obviousness or anti-anticipation arguments based on 'technical prejudice.' It is this: a prejudice can only come into play once you have had the idea. You cannot reject an idea as technically unfeasible or impractical unless you have had it first. And if you have had it first, how can the idea be anything other than old or obvious? Yet when a patent demonstrates that an established prejudice is unfounded — that what was considered unfeasible does in fact work, it would be contrary to the point of the patent system to hold the disclosure unpatentable.

…

27. Patentability is justified because the prior idea which was thought not to work must, as a piece of prior art, be taken as it would be understood by the person skilled in the art. He will read it with the prejudice of such a person. So that which forms part of the state of the art really consists of two things in combination, the idea and the prejudice that it would not work or be impractical. A patentee who contributes something new by showing that, contrary to the mistaken prejudice, the idea will work or is practical has shown something new. He has shown that an apparent 'lion in the path' is merely a paper tiger. Then his contribution is novel and non-obvious and he deserves his patent.

28. Where, however, the patentee merely patents an old idea thought not to work or to be practical and does not explain how or why, contrary to the prejudice, that it does work or is practical, things are different. Then his patent contributes nothing to human knowledge. The lion remains at least apparent (it may even be real) and the patent cannot be justified."

"… The principle is that you cannot have a patent for doing something which the skilled person would regard as old or obvious but difficult or impossible to do, if it remains equally difficult or impossible to do when you have read the patent. To put it another way, the perceived problem must be solved by the patent."

It is not in dispute that, when Floyd LJ said "must be solved" in this passage, he must have meant "must plausibly be solved".

" In the present case there is no doubt that the skilled team in this field would have a keen awareness of the likelihood and risks of side effects with any mechanism, including ß3-AR agonism. A main potential cause of side effects for a ß3-AR agonist under consideration would be off-target effects if the compound turned out to be an agonist of ß1 or ß2 as well and the skilled team might be deterred from proceeding with a compound whose selectivity was unknown. But since the Patent contains nothing to say whether or to what extent mirabegron was selective for ß3 over ß1 and ß2, Astellas cannot rely on this, as its Counsel accepted. … "

"19. … the patentee is entitled to have the question of obviousness determined by reference to his claim and not to some vague paraphrase based upon the extent of his disclosure in the description. There is no requirement in the EPC or the statute that the specification must demonstrate by experiment that the invention will work …

39. … there is in my opinion no reason as a matter of principle why, if a specification passes the threshold test of disclosing enough to make the invention plausible, the question of obviousness should be subject to a different test according to the amount of evidence which the patentee presents to justify a conclusion that his patent will work."

Conclusion

Lord Justice Stuart-Smith:

Lady Justice Falk: