Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

England and Wales Court of Appeal (Civil Division) Decisions

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> England and Wales Court of Appeal (Civil Division) Decisions >> Liverpool Gin Distillery Ltd & Ors v Sazerac Brands, LLC & Ors [2021] EWCA Civ 1207 (05 August 2021)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWCA/Civ/2021/1207.html

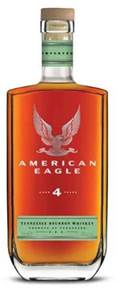

Cite as: [2021] ETMR 57, [2021] EWCA Civ 1207

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

Neutral Citation Number: [2021] EWCA Civ 1207

Case No: A3/2020/2126

IN THE COURT OF APPEAL (CIVIL DIVISION)

ON APPEAL FROM THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE, BUSINESS AND PROPERTY COURTS, INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY LIST

Fancourt J

Royal Courts of Justice

Strand, London, WC2A 2LL

Date: 5 August 2021

Before :

LORD JUSTICE ARNOLD

LADY JUSTICE ELISABETH LAING

and

LORD JUSTICE BIRSS

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Between :

|

|

(1) LIVERPOOL GIN DISTILLERY LIMITED (2) HALEWOOD INTERNATIONAL LIMITED (3) HALEWOOD INTERNATIONAL BRANDS LIMITED |

Appellants |

|

|

- and - |

|

|

|

(1) SAZERAC BRANDS, LLC (2) SAZERAC COMPANY, INC (3) SAZERAC UK LIMITED |

Respondents |

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Simon Malynicz QC and Jeremy Heald (instructed by Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom (UK) LLP) for the Appellants

Daniel Alexander QC and Maxwell Keay (instructed by Fieldfisher LLP) for the Respondents

Hearing date : 29 July 2021

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Judgment Approved

Covid-19 Protocol: This judgment was handed down remotely by circulation to the parties’ representatives by email, release to BAILII and publication on the Courts and Tribunals Judiciary website. The date and time for hand-down is deemed to be 10.30am on 5 August 2021.

Lord Justice Arnold:

Introduction

1. This is a trade mark dispute. The Respondents (“Sazerac”) own two trade marks consisting of the words EAGLE RARE (“the Trade Marks”), and have marketed a Kentucky straight bourbon whiskey under that brand name since 2001. In February 2019 the Appellants (“Halewood”) launched a Tennessee straight bourbon whiskey under the sign AMERICAN EAGLE (“the Sign”). Fancourt J held for the reasons given in his judgment dated 10 September 2020 [2020] EWHC 2424 (Ch), [2020] ETMR 62 that Halewood had thereby infringed the Trade Marks. Although he found that there was no likelihood of direct confusion, he concluded that there was a likelihood of indirect confusion. Halewood appeal against that conclusion with permission granted by the judge. Sazerac support the judge’s conclusion on indirect confusion, and in the alternative contend by a respondent’s notice that the judge was wrong to reject their case that Halewood’s use of the Sign took unfair advantage of the reputation of the Trade Marks.

The Trade Marks

2. The Trade Marks are:

i) UK Trade Mark No. 1148476 registered as of 10 February 1981 in respect of “whisky” in Class 33 with a disclaimer of any exclusive right to the word RARE.

ii) EU Trade Mark No. 2597961 registered as of 1 March 2002 in respect of (among other goods) “bourbon whiskey” in Class 33. As a result of Brexit, this Trade Mark has now been converted into a UK registration. It is common ground, however, that this is irrelevant to Sazerac’s claim for infringement and the issues arising on the appeal.

The bourbon market in the UK

3. The judge had the benefit of expert evidence as to the bourbon market in the UK given by Robert Allanson (whose qualifications include being editor of Whisky Magazine) for Sazerac and Tristan Stephenson (whose qualifications include being the author of two books on whiskies, one of which is specifically about American whiskey) for Halewood. On the evidence the judge found as follows:

15. The total volume of US whiskey sold in the UK in 2018 and 2019 was around 1.4 million 9-litre cases annually, worth about £650 million. Between about 1.2 and 1.3 million cases are Jack Daniels and Jim Beam mass market products. After allowing for other mass market products, it can therefore be seen that the sales volumes for premium and super premium brands are quite low. Within that space, certain better known brands (Maker’s Mark, Bulleit, Wild Turkey and Woodford Reserve) occupy much of the ground. …”

The rival products

4. The judge made the following findings concerning the rival products:

24. … the high quality upper middle and premium parts of the bourbon market are relatively underpopulated by brands in the UK and EU markets. These brands are set comfortably above the mass market brands though the increase in price is not so steep as to deter lower level drinkers from experimenting on occasions with the quality brands. Eagle Rare 17 year old is on a much higher level with few if any peers. American Eagle 8 year old will be a direct competitor with Eagle Rare 10 year old, with American Eagle 12 year old at a slightly higher and considerably more expensive level. The 4 year old version is a little lower in price and will compete both with mass market brands and to some extent with the middle or upper-middle level products such as Eagle Rare. The volume of sales through multiples to which the Defendants aspire will be far in excess of sales and exposure of Eagle Rare. As a result, in time, more consumers of bourbon whiskey would become aware of American Eagle than are aware of Eagle Rare.”

5. Images of the Eagle Rare 10 year old and American Eagle 4 year old products are reproduced below.

The legal framework

6. Sazerac’s claim for infringement of the EU Trade Mark was brought under Article 9(2)(b) and (c) of European Parliament and Council Regulation 2017/1001/EU of 14 June 2017 on the European Union trade mark (“the Regulation”). Sazerac’s claim for infringement of the UK Trade Mark was brought under section 10(2) and (3) of the Trade Marks Act 1994 (“the Act”) which implement Article 10(2)(b) and (c) of European Parliament and Council Directive 2015/2436/EU of 16 December 2015 to approximate the laws of the Member States relating to trade marks (recast) (“the Directive”). It is common ground that there is no difference between the law applicable under the Regulation and the law applicable under the Act for the purposes of this case.

Likelihood of confusion: the law

7. In order to establish infringement under Article 9(2)(b) of the Regulation/Article 10(2)(b) of the Directive, six conditions must be satisfied: (i) there must be use of a sign by a third party within the relevant territory; (ii) the use must be in the course of trade; (iii) it must be without the consent of the proprietor of the trade mark; (iv) it must be of a sign which is at least similar to the trade mark; (v) it must be in relation to goods or services which are at least similar to those for which the trade mark is registered; and (vi) it must give rise to a likelihood of confusion on the part of the public. In the present case, there is no issue as to conditions (i)-(v).

8. The manner in which the requirement of a likelihood of confusion in Article 9(2)(b) of the Regulation and Article 10(2)(b) of the Directive, and the corresponding provisions concerning relative grounds of objection to registration in both the Directive and the Regulation, should be interpreted and applied has been considered by the Court of Justice of the European Union in a large number of decisions. The Trade Marks Registry has adopted a standard summary of the principles established by these authorities for use in the registration context. The current version of this summary, which was approved by this Court in Comic Enterprises Ltd v Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp [2016] EWCA Civ 41, [2016] FSR 30 at [31]-[32] (Kitchin LJ), is as follows:

“(a) the likelihood of confusion must be appreciated globally, taking account of all relevant factors;

(b) the matter must be judged through the eyes of the average consumer of the goods or services in question, who is deemed to be reasonably well informed and reasonably circumspect and observant, but who rarely has the chance to make direct comparisons between marks and must instead rely upon the imperfect picture of them he has kept in his mind, and whose attention varies according to the category of goods or services in question;

(c) the average consumer normally perceives a mark as a whole and does not proceed to analyse its various details;

(d) the visual, aural and conceptual similarities of the marks must normally be assessed by reference to the overall impressions created by the marks bearing in mind their distinctive and dominant components, but it is only when all other components of a complex mark are negligible that it is permissible to make the comparison solely on the basis of the dominant elements;

(e) nevertheless, the overall impression conveyed to the public by a composite trade mark may, in certain circumstances, be dominated by one or more of its components;

(f) and beyond the usual case, where the overall impression created by a mark depends heavily on the dominant features of the mark, it is quite possible that in a particular case an element corresponding to an earlier trade mark may retain an independent distinctive role in a composite mark, without necessarily constituting a dominant element of that mark;

(g) a lesser degree of similarity between the goods or services may be offset by a greater degree of similarity between the marks, and vice versa;

(h) there is a greater likelihood of confusion where the earlier mark has a highly distinctive character, either per se or because of the use that has been made of it;

(i) mere association, in the strict sense that the later mark brings the earlier mark to mind, is not sufficient;

(j) the reputation of a mark does not give grounds for presuming a likelihood of confusion simply because of a likelihood of association in the strict sense;

(k) if the association between the marks creates a risk that the public might believe that the respective goods or services come from the same or economically-linked undertakings, there is a likelihood of confusion.”

9. The same principles are applicable when considering infringement, although it is necessary for this purpose to consider the actual use of the sign complained of in the context in which the sign has been used: see Case C-533/06 O2 Holdings Ltd v Hutchison 3G UK Ltd [2008] ECR I-4231 at [64], and Case C-252/12 Specsavers International Healthcare Ltd v Asda Stores Ltd [EU:C:2013:497] at [45]. As Kitchin LJ (with whom Sir John Thomas PQBD and Black LJ agreed) put it in Specsavers International Healthcare Ltd v Asda Stores Ltd [2012] EWCA Civ 24, [2012] FSR 19 at [87]:

“In my judgment the general position is now clear. In assessing the likelihood of confusion arising from the use of a sign the court must consider the matter from the perspective of the average consumer of the goods or services in question and must take into account all the circumstances of that use that are likely to operate in that average consumer’s mind in considering the sign and the impression it is likely to make on him. The sign is not to be considered stripped of its context.”

10. It is well established that there are two main kinds of confusion which trade mark law aims to protect a trade mark proprietor against (see in particular Case C-251/95 Sabel BV v Puma AG [1997] ECR I-6191 at [16]). The first, often described as “direct confusion”, is where consumers mistake the sign complained of for the trade mark. The second, often described as “indirect confusion”, is where the consumers do not mistake the sign for the trade mark, but believe that goods or services denoted by the sign come from the same undertaking as goods or services denoted by the trade mark or from an undertaking which is economically linked to the undertaking responsible for goods or services denoted by the trade mark.

11. In LA Sugar Ltd v Back Beat Inc (O/375/10) Iain Purvis QC sitting as the Appointed Person said:

“16. Although direct confusion and indirect confusion both involve mistakes on the part of the consumer, it is important to remember that these mistakes are very different in nature. Direct confusion involves no process of reasoning - it is a simple matter of mistaking one mark for another. Indirect confusion, on the other hand, only arises where the consumer has actually recognized that the later mark is different from the earlier mark. It therefore requires a mental process of some kind on the part of the consumer when he or she sees the later mark, which may be conscious or subconscious but, analysed in formal terms, is something along the following lines: ‘The later mark is different from the earlier mark, but also has something in common with it. Taking account of the common element in the context of the later mark as a whole, I conclude that it is another brand of the owner of the earlier mark’.

17. Instances where one may expect the average consumer to reach such a conclusion tend to fall into one or more of three categories:

(a) where the common element is so strikingly distinctive (either inherently or through use) that the average consumer would assume that no-one else but the brand owner would be using it in a trade mark at all. This may apply even where the other elements of the later mark are quite distinctive in their own right (‘26 RED TESCO’ would no doubt be such a case).

(b) where the later mark simply adds a non-distinctive element to the earlier mark, of the kind which one would expect to find in a sub-brand or brand extension (terms such as ‘LITE’, ‘EXPRESS’, ‘WORLDWIDE’, ‘MINI’ etc.).

(c) where the earlier mark comprises a number of elements, and a change of one element appears entirely logical and consistent with a brand extension (‘FAT FACE’ to ‘BRAT FACE’ for example).”

12. This is a helpful explanation of the concept of indirect confusion, which has frequently been cited subsequently, but as Mr Purvis made clear it was not intended to be an exhaustive definition. For example, one category of indirect confusion which is not mentioned is where the sign complained of incorporates the trade mark (or a similar sign) in such a way as to lead consumers to believe that the goods or services have been co-branded and thus that there is an economic link between the proprietor of the sign and the proprietor of the trade mark (such as through merger, acquisition or licensing).

13. As James Mellor QC sitting as the Appointed Person pointed out in Cheeky Italian Ltd v Sutaria (O/219/16) at [16] “a finding of a likelihood of indirect confusion is not a consolation prize for those who fail to establish a likelihood of direct confusion”. Mr Mellor went on to say that, if there is no likelihood of direct confusion, “one needs a reasonably special set of circumstances for a finding of a likelihood of indirect confusion”. I would prefer to say that there must be a proper basis for concluding that there is a likelihood of indirect confusion given that there is no likelihood of direct confusion.

14. “Likelihood of confusion” usually refers to the situations described in paragraph 10 above. As this Court held in Comic Enterprises, however, it also embraces situations where consumers believe that goods or services denoted by the trade mark come from the same undertaking as goods or services denoted by the sign or an economically-linked undertaking (sometimes referred to as “wrong way round confusion”).

Likelihood of confusion: the judgment

15. The judge’s assessment of the likelihood of confusion may be summarised as follows.

16. At [8] the judge noted that the allegation of infringement fell to be assessed at the date on which Halewood had started using the Sign, namely February 2019.

17. At [47]-[56] the judge considered the characteristics of the average consumer of bourbon in the UK and concluded that “there is a greater than usual degree of brand loyalty within the bourbon market and so, on average, the consumer has a somewhat higher degree of attentiveness than a consumer of certain other spirits”.

18. In this context the judge referred to some evidence given in cross-examination by Mr Allanson:

“53. … Asked whether consumers were well-used to distinguishing between brands with similar names, he agreed that they were if they remembered the names. Asked to comment on whether a consumer would assume that Yellow Rose whiskey came from Four Roses, Mr Allanson said that they would, unless they were able to examine the labels with the specialist knowledge that he had. He said that there was potential for confusion with the Heaven Hill and Heaven’s Door brands in the US. But he agreed that the consumer in the premium sector would take care to distinguish between brands.

…

56. I accept Mr Allanson’s evidence that (were all the brands available in the UK and EU) the average consumer would be likely to be confused about the identity or provenance of Four Roses and Yellow Rose, and Heaven Hill and Heaven’s Door. That evidence was given as an instinctive reaction to questions; it was convincingly given and had a ring of truth to it. Although the names are different, a non-specialist would be likely to assume that there was some link between them, judging by their names.”

19. At [57] the judge noted that there was no dispute that the Sign was similar to the Trade Marks and that the goods in relation to which the Sign had been used were identical to goods for which the Trade Marks were registered.

20. The judge’s assessment of the extent of visual and conceptual similarity between the sign and the Trade Marks was as follows:

“59. The mark Eagle Rare self-evidently comprises two separate words, one of which is a strong substantive and the other an adjective, in the nature of a qualification or description. That is not to treat the mark as if it were Eagle rather than Eagle Rare but only to observe that the average consumer would regard the word Eagle as the more distinctive component and the word Rare as relating to the quality of the product. Use of ‘rare’ in this way is common in the aged spirits market and would be recognised as such by the average consumer of bourbon. The words ‘Eagle Rare’ would not in my judgment be read by the average consumer as describing or referring to a rare species of eagle, e.g. a golden eagle.

60. The sign American Eagle is similar in that it includes the word ‘Eagle’, though as the second rather than the lead term, and in that Eagle is qualified by an adjective, ‘American’. The word American is also strong, much stronger than "Rare", so that the sign would more naturally be read as a composite whole. That is because the two words are more naturally linked than the words Eagle and Rare, when read in that order. The word ‘American’ has additional visibility because it comes first. I reject the Claimants’ argument that ‘American’ is weak because it does no more than state the obvious, viz that bourbon is an American product. There is nevertheless similarity in visual terms, given that the substantive Eagle appears in both mark and sign as a strong component.

61. Conceptually, the sign American Eagle conjures up an image distinct from something or anything American and an eagle: it conjures up an image of a bald eagle, a particular type of eagle native to North America and an iconic symbol (and the national bird) of the United States of America. I therefore consider that, conceptually, the trade mark and the sign are distinct and not strongly similar.”

21. At [62] the judge concluded that there was “some similarity” between the Sign and the Trade Marks in aural terms bearing in mind that there was evidence that the Trade Marks were occasionally abbreviated to EAGLE. The judge’s overall assessment at [63] was that there was “a significant degree of similarity, but not overwhelming similarity” between the Sign and the Trade Marks.

22. Having referred at [29] and [64] to the passage in Specsavers v Asda quoted above, the judge assessed the context of use of the Sign at [65] as follows:

“The Defendants are using the sign in the context of the bourbon whiskey market in the UK and EU. The sign is used on bottles of whiskey that are sold in retail outlets, in bars, clubs and restaurants and online - exactly the same market in which Eagle Rare is sold. I am not persuaded that there is any other context or circumstances that are material.”

23. At [66] the judge concluded that, having regard to the degree of attention that would be paid by consumers and the differences between the Sign and the Trade Marks, there was “little likelihood that a significant proportion of the bourbon buying public would be confused into thinking that American Eagle is the same product as Eagle Rare, or vice versa”.

24. At [67] the judge found that, given the inherently distinctive character of the Trade Marks, in that no other bourbon whiskey in the UK had a name that included the word “eagle”, the average consumer who saw or heard the Sign would be likely to call the Trade Marks to mind. He went on to say that there would be “a natural association in the mind of the consumer between a new brand using the word ‘eagle’ and Eagle Rare, given the coincidence of the product and the name, even if the average consumer would not instinctively consider them to be one and the same product”. The judge noted at [68], however, that this association was insufficient to constitute a likelihood of confusion.

25. At [69] the judge said:

26. Having cautioned himself at [70] that a finding of indirect confusion must be founded upon evidence and inference and not upon speculation, the judge reasoned as follows:

“71. I find that it is both common and well-known in the spirits market in the UK and the EU, including their respective bourbon sub-markets, for producers not only to have different expressions of brands (i.e. different age statements or special releases or ‘single cask’ products, and the like) but also to release different products with different names, that may or may not allude directly or indirectly to another brand, which are made in the same distillery, by the same distiller or by a distiller in the same group as (or licensed by) the originating distiller. Mr Stephenson very readily accepted in cross-examination in general terms that this was so. He did refer to the presence of the senior brand name on the bottle somewhere, but he was answering a question about how different expressions of the same brand were presented and doing so by reference to actual examples of this in the documentary evidence. I did not take his comment to be to the effect that all sub-brands or connected brands include on the label a reference to the main brand. In any event, the average consumer would not have that expectation or scrutinise the label to ascertain whether any link was to be found.

72. There was no evidence of any actual confusion of a consumer of American Eagle, though this is not wholly surprising given the novelty, low-key launch and limited release to date of that brand, and further given the fact that Mr Bradbury had not instructed his sales team to inquire into and report on any incidents of confusion between American Eagle and Eagle Rare specifically. It is not uncommon in such cases for there to be little hard evidence of actual confusion. In those circumstances, the Claimants must satisfy me that it is inherently likely that such confusion will arise.

73. I consider that there is a likelihood of a significant proportion of the bourbon markets in the UK and EU being confused about whether Eagle Rare and American Eagle are connected brands. It is common for connected brands to have similar names: see the examples given in para 69 above. The average consumer would be aware of the fact that brands have different expressions and connected products, and that distillers can make more than one brand. It is natural to consider, as Mr Allanson did when presented for the first time with ‘Yellow Rose’ and ‘Heaven’s Door’, that there was a connection with the ‘Four Roses’ and ‘Heaven Hill’ brands. He had not heard of the smaller brands, so he approached this question in the same way that an average consumer would, though he accepted that with scrutiny of the label and using his expertise the difference could be established.

74. The position with Eagle Rare and American Eagle is similar, in that prior to American Eagle's launch there was no other bourbon in the relevant market using the name ‘Eagle’ as part of its brand name. It is a distinctive component of the brand name. Another identical product in the same market with ‘Eagle’ in its name would not only call Eagle Rare to mind but would be likely to cause the average consumer to assume that they were connected in some way. That is so even though American Eagle has a strong composite identity, because of the presence of the word ‘Eagle’. I do not consider that the fact that American Eagle is Tennessee bourbon rather than Kentucky bourbon makes any difference, since the average consumer will not have this distinction in mind, and even if they did it would not negate the possibility of an economic link between the respective undertakings. It goes only to support the conclusion that the products would not mistakenly be thought to be the same.

75. Confusion is more likely when a trade mark is distinctive. The test is whether that association between the mark and the sign creates a risk that the public might believe that the respective goods or services come from the same or economically-linked undertakings. I consider that there is such a risk because the product is identical, the names have marked similarity - indicative of a possible connection between them - and because the existence of connected brands using similar names is well-known to the public. In particular, once American Eagle 4 year old is established and becomes more widely known than Eagle Rare, having been positioned by the Defendants to compete with Jack Daniels and the like in the mass market, it will be natural for a consumer to assume that Eagle Rare is a special version of American Eagle.”

The appeal

27. Since the judge’s conclusion that there was a likelihood of indirect confusion was a multi-factorial evaluation this Court can only intervene if he erred in law or in principle: cf. Actavis Group PTC EHF v ICOS Corp [2019] UKSC 15, [2019] Bus LR 1318 at [78]-[81] (Lord Hodge).

28. Halewood do not suggest that the judge misdirected himself as to the law, but nevertheless contend that he erred in principle. They challenge his conclusion with respect to indirect confusion on five grounds. Although counsel for Halewood placed ground 5 at the forefront of his argument, it is convenient to address grounds 1-4 first.

29. Grounds 1-4 all concern the principle of contextual assessment of the use of the sign complained of. Halewood contend that, despite referring to this principle twice in his judgment, the judge fell into error in his application of the principle in three respects.

30. First, Halewood point out that the judge stated at [29] that “the trade marks in issue are word marks only, not figurative marks, so the comparative trade dress of the Claimants’ and the Defendants’ products are immaterial”. Counsel for Halewood argued that this was erroneous, and that it was necessary to take the trade dress or get-up of Halewood’s product - but not Sazerac’s product - into account. Counsel for Halewood did not rely upon any particular aspect of the get-up of Halewood’s product as dispelling any likelihood of confusion that might arise from the Sign, however. Moreover, notwithstanding what he said at [29], the judge did consider at [74] whether the fact (which is stated on the label) that Halewood’s product is Tennessee bourbon (rather than Kentucky bourbon like Sazerac’s product) would avoid any indirect confusion. He found that it would not, and there is no challenge to that finding. If that difference would not avoid confusion, it is difficult to see that any other aspect of the get-up would do so.

31. Instead, counsel for Halewood argued that the judge had failed to take into account the fact that the get-up of Halewood’s product did not contain anything to indicate that AMERICAN EAGLE was a related brand to EAGLE RARE. This argument does not depend on what is present in the get-up, however, but on what is absent. It does not show that the judge made any error in applying the principle of contextual assessment. Whether the judge made any error of principle in finding that there was a likelihood of indirect confusion is a different question which I shall consider below.

32. Secondly, Halewood contend that the judge had failed to take into account consumers’ “mindset” as to the type of brands which engage in brand extensions. Whether or not this is properly described as part of the context of use of the Sign, however, this is something that the judge did consider at [69], [71] and [73]. Again, therefore, this does not establish that the judge made any error in applying the principle of contextual assessment, but whether the judge made an error of principle in finding that there was a likelihood of indirect confusion is a separate question.

33. Thirdly, Halewood contend that the judge was wrong in the last sentence of [75] to have regard to what might happen in the future. There is nothing in this point. The judge correctly directed himself that the relevant date was February 2019, and plainly his findings in the first three sentences of [75] refer to the position as at that date. The judge was not precluded, in assessing the likelihood of confusion at that date, from taking into account probable future developments. On the contrary, he would have been in error had he not done so, since it is of the essence of the test of likelihood of confusion that it is forward-looking.

34. I turn, therefore, to ground 5, namely that the judge erred in principle in finding that there was a likelihood of indirect confusion. Halewood contend that the judge erred in four respects.

35. First, Halewood contend that the reasons given by the judge for concluding that there was no likelihood of direct confusion, and in particular the conceptual significance of the Sign, should equally have led him to conclude that there was no likelihood of indirect confusion. This simply does not follow, however. As the judge correctly recognised, direct confusion and indirect confusion are different species of confusion. The reasons that the judge gave for concluding that the Sign would not be mistaken by the average consumer for the Trade Marks did not preclude the possibility of the average consumer believing that they were related brands.

36. Secondly, Halewood contend that the judge was wrong to place weight on the evidence of Mr Allanson about Yellow Rose/Four Roses and Heaven’s Door/Heaven Hill because Mr Allanson was not an expert in the likelihood of confusion and therefore his evidence on this topic was inadmissible: see European Ltd v Economist Newspaper Ltd [1998] FSR 283 at 290-291 (Millett LJ) and esure Insurance Ltd v Direct Line Insurance plc [2008] EWCA Civ 842, [2008] RPC 34 at [62] (Arden LJ), [77] (Jacob LJ) and [80] Maurice Kay LJ). Furthermore, Halewood contend that Mr Allanson was not a proxy for the average consumer precisely because he was an expert and that the evidence was in any event irrelevant to the issue of whether there was a likelihood of indirect confusion between the Sign and the Trade Marks.

37. As counsel for Sazerac pointed out, the judge cannot be blamed for taking this evidence into account given that it was elicited by Halewood in cross-examination and given that the authorities mentioned in the preceding paragraph were not cited to him. Furthermore, the context in which the judge considered the evidence was that of assessing the degree of attention which would be paid by the average consumer. Although Halewood had hoped to elicit evidence that the average consumer of bourbon would be sufficiently attentive not to be misled by similar brand names, the witness disagreed with this. As the judge explained, Mr Allanson gave his reaction as a consumer rather than as an expert in the sense that he was not aware of either Yellow Rose or Heaven’s Door.

38. That said, strictly speaking, Halewood is correct that the evidence was inadmissible. However, the only reference to this evidence that the judge made when assessing the likelihood of indirect confusion was in [73]. In context, the judge simply used this as an illustration of how an average consumer may react to similar brand names given their awareness of “the fact that brands have different expressions and connected products, and that distillers can make more than one brand”. The judge did not make the mistake of saying that, because Mr Allanson had expressed the opinion that consumers would think that Yellow Rose and Heaven’s Door were connected with Four Roses and Heaven Hill, therefore consumers would think that AMERICAN EAGLE was connected with EAGLE RARE.

39. Thirdly, Halewood criticise the judge’s finding at [71] that it was common and well-known in the whisk(e)y and bourbon markets for producers to release different products with different names that alluded directly or indirectly to other brands of theirs, without necessarily referring to the main brand on the label. Counsel for Halewood submitted that this finding was not supported by the evidence of Mr Stephenson.

40. Before turning to the detail of this criticism, it is important to put it in context. As counsel for Sazerac pointed out, it can be seen from [69] that the judge relied not only on the evidence of Mr Stephenson but also on the evidence of Mr Hainsworth. As counsel for Sazerac also pointed out, Mr Hainsworth accepted that the practice of brand extension, exemplified by Halewood’s own Whitley Neill and J.J. Whitley brands for gin and vodka, was very common in the whisk(e)y market, including the bourbon category.

41. Counsel for Halewood submitted that the judge was wrong when he said at [71] that he had not taken it to be Mr Stephenson’s evidence that all sub-brands or connected brands included a reference to the main brand on the label. Although this submission appears to receive some support from the transcript, the judge set out his understanding of the effect of Mr Stephenson’s evidence and the transcript may not fully convey that.

42. More importantly, counsel for Halewood argued that, in considering the examples referred to at [69], the judge had overlooked two significant points. The first point was that there was no evidence as to how visible to consumers those examples had been whether through sales or marketing at the relevant date. This is correct, but in my view it is immaterial given that they were merely examples of what was accepted to be a common practice. The second point is that both Gentleman Jack and Winter Jack bore the name Jack Daniel’s on the labels as well as the related brand names. Thus the only examples where this was not so were The Snow Grouse and The Black Grouse, alluding to The Famous Grouse, and those were Scotch whiskies rather than bourbons. It is true that the judge did not explicitly mention any of these distinctions, but it is clear that he was aware of them since he had been shown images of all these products which were included in the trial bundles. In my view they do not undermine his finding in [71].

43. In any event, what matters is whether the judge was entitled to conclude that some consumers of bourbon confronted with AMERICAN EAGLE would be likely to believe that it was a related brand to EAGLE RARE. Even if Halewood’s criticisms which I have considered in the two preceding paragraphs are well founded, I consider that the judge was entitled to take that view. In particular, I consider that he was right to infer that there was a likelihood of some consumers thinking that EAGLE RARE was a special version of AMERICAN EAGLE. Contrary to the submission of counsel for Halewood, this was not speculation given the judge’s findings of fact at [24]. Moreover, the judge was correct to proceed on the basis that consumers would not necessarily scrutinise the label to check whether or not there was a link. Trade mark law is all about consumers’ unwitting assumptions, not what they can find out if they think to check.

44. Fourthly, Halewood contend that the judge failed to take into account the fact that Sazerac had not engaged in brand extension of EAGLE RARE and that it was too niche a product for that to be considered logical or likely. Reading the judgment as a whole, however, it is plain that these are matters which he did take into account. They did not compel the conclusion that there was no likelihood of indirect confusion.

Conclusion

45. For the reasons given above I would dismiss Halewood’s appeal. It follows that it is unnecessary to consider Sazerac’s respondent’s notice.

Elisabeth Laing LJ:

46. I agree.

Birss LJ:

47. I also agree.