Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

Court of Justice of the European Communities (including Court of First Instance Decisions)

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> Court of Justice of the European Communities (including Court of First Instance Decisions) >> Inex v OHMI - Wiseman (ReprEsentation d'une peau de vache) (Intellectual property) [2006] EUECJ T-153/03 (13 June 2006)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/eu/cases/EUECJ/2006/T15303.html

Cite as: [2006] EUECJ T-153/3, [2006] EUECJ T-153/03, ECLI:EU:T:2006:157, EU:T:2006:157

[New search] [Contents list] [Help]

IMPORTANT LEGAL NOTICE - The source of this judgment is the web site of the Court of Justice of the European Communities. The information in this database has been provided free of charge and is subject to a Court of Justice of the European Communities disclaimer and a copyright notice. This electronic version is not authentic and is subject to amendment.

JUDGMENT OF THE COURT OF FIRST INSTANCE (Second Chamber)

13 June 2006 (*)

(Community trade mark - Opposition proceedings - Application for a figurative mark consisting of a representation of a cowhide in black and white - Earlier national figurative trade mark comprising in part a representation of a cowhide in black and white - Distinctive character of an element of a trade mark - No likelihood of confusion - Rejection of the opposition - Article 8(1)(b) of Regulation (EC) No 40/94)

In Case T-153/03,

Inex SA, established in Bavegem (Belgium), represented by T. van Innis, lawyer,

applicant,

v

Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (OHIM), represented initially by U. Pfleghar and G. Schneider, and subsequently by G. Schneider and A. Folliard-Monguiral, acting as Agents,

defendant,

the other party to the proceedings before the Board of Appeal of the Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs), intervener before the Court of First Instance, being

Robert Wiseman & Sons Ltd, established in Glasgow (United Kingdom), represented by A. Roughton, Barrister,

ACTION brought against the decision of the Second Board of Appeal of the Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) of 4 February 2003 (Case R 106/2001-2), relating to opposition proceedings between Inex SA and Robert Wiseman & Sons Ltd,

THE COURT OF FIRST INSTANCEOF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES (Second Chamber),

composed of J. Pirrung, A.W.H. Meij and I. Pelikánová, Judges,

Registrar: C. Kristensen, Administrator,

having regard to the application lodged at the Registry of the Court of First Instance on 18 April 2003,

having regard to the responses of the intervener and of the Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) lodged at the Registry of the Court of First Instance on 4 and 12 September 2003 respectively,

further to the hearing on 7 September 2005,

gives the following

Judgment

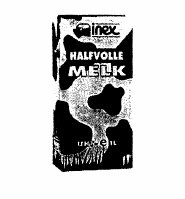

Background to the dispute

1 On 1 April 1996, the intervener filed an application for a Community trade mark at the Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) ("the Office") under Council Regulation (EC) No 40/94 of 20 December 1993 on the Community trade mark (OJ 1994 L 11, p. 1), as amended.

2 The mark in respect of which registration was sought is the following figurative sign:

3 The goods for which registration was sought fall within Classes 29, 32 and 39 under the Nice Agreement Concerning the International Classification of Goods and Services for the Purposes of the Registration of Marks of 15 June 1957, as revised and amended, and correspond, for each of those classes, to the following description:

- Class 29: "Milk, milk beverages, milk products, dairy products, cream and yoghurt";

- Class 32: "Beers; mineral and aerated waters and other non-alcoholic drinks; fruit drinks and fruit juices, syrups and other preparations for making beverages";

- Class 39: "Collection, delivery, distribution and transport of goods by road".

4 On 27 October 1997, that application for registration was published in Community Trade Marks Bulletin No 25/97.

5 On 22 January 1998, the applicant filed a notice of opposition under Article 42 of Regulation No 40/94 against that Community trade mark application, relying on Article 8(1)(b) of Regulation No 40/94.

6 The opposition was based on the earlier figurative trade mark No 580 538, registered in the Benelux countries on 17 October 1995 for goods in Classes 29 and 30 under the Nice Agreement and reproduced below:

7 The opposition concerned some of the goods covered by the earlier mark, namely "Milk and milk products, dairy products", and was directed against "Milk, milk beverages and milk products, dairy products" referred to by the trade mark application. In reply to the observations of the intervener, the applicant stated that the opposition was directed against all of the goods in Class 29 designated in the trade mark application, including "cream and yogurt".

8 By decision of 29 November 2000, the Opposition Division rejected the opposition on the ground that the signs at issue were sufficiently different not to give rise to any likelihood of confusion.

9 On 22 January 2001, the applicant filed a notice of appeal at the Office under Articles 57 to 62 of Regulation No 40/94 against the decision of the Opposition Division.

10 By decision of 4 February 2003 ("the contested decision"), the Second Board of Appeal of the Office dismissed the appeal. The Board of Appeal stated that strong visual differences existed between the marks at issue. It considered, however, that the marks at issue were conceptually similar since they both called to mind the idea of a cow. However, on account of the fact that that similarity related to an aspect which was not very distinctive for the goods in question, it was not considered sufficient to lead to the conclusion that there was a likelihood of confusion. Accordingly, despite the fact that the two marks designated identical goods, the Board of Appeal concluded that there was no likelihood of confusion.

Forms of order sought

11 The applicant claims that the Court should:

- annul the contested decision;

- order the Office to pay the costs.

12 The Office contends that the Court should:

- dismiss the action;

- order the applicant to pay the costs.

13 The intervener contends that the Court should:

- dismiss the action;

- order the applicant to pay the costs of the intervener.

Law

14 The applicant relies on a single plea in law alleging infringement of Article 8(1)(b) of Regulation No 40/94.

Arguments of the parties

15 The applicant claims that the Board of Appeal failed to have regard to the rule of interdependence between similarity between the trade marks and similarity between the goods and services, as stated in the judgments in Case C-39/97 Canon [1998] ECR I-5507 and Case C-342/97 Lloyd Schuhfabrik Meyer [1999] ECR I-3819, according to which a lesser degree of similarity between the goods or services covered may be offset by a greater degree of similarity between the conflicting marks, and vice versa.

16 Further, the Board of Appeal failed to have regard to the rule under which the global assessment of the similarity of the signs at issue must be based on the overall impression given by them, bearing in mind their distinctive and dominant components, and the fact that the average consumer only rarely has the chance to make a direct comparison between the marks, of which he will retain only an imperfect picture. The applicant submits in this regard that the Board of Appeal should have found that the likelihood of confusion between the signs at issue is increased by the fact that the goods in question are targeted at the general public.

17 The applicant claims, in addition, that the Board of Appeal contradicted itself in finding, on the one hand, that the figurative aspect of the mark applied for, representing a cowhide, was identical to the dominant element of the earlier mark, and, on the other hand, that the marks at issue displayed strong visual differences. According to the applicant, the Board of Appeal should have found that there was a visual similarity between those two trade marks, one of which consists exclusively of the dominant element of the other.

18 The applicant submits, finally, that the dominant element of the earlier mark is necessarily distinctive owing to the fact that one of the marks is exclusively composed of that element. In that respect, in the Benelux countries the dominant element of the earlier mark is distinctive since its packaging is the only one, in those countries, which bears a representation of a cowhide in black and white as its dominant element. In reply to the written questions of the Court and at the hearing, the applicant stated that, in so far as the intervener did not contest that the earlier mark was the only one, in the Benelux countries, to use the drawing of a cowhide as its dominant element, it has implicitly admitted that that element is distinctive. The Court would infringe the principle under which the parties delimit the scope of the case if it were to call into question that statement. The applicant also submits that the dominant element of its mark cannot but be distinctive, having regard to the highly competitive nature of the market.

19 The Office and the intervener challenge the applicant's arguments.

Findings of the Court

20 Under Article 8(1)(b) of Regulation No 40/94, upon opposition by the proprietor of an earlier trade mark, the trade mark applied for is not to be registered if because of its identity with or similarity to the earlier trade mark and the identity or similarity of the goods or services covered by the trade marks there exists a likelihood of confusion on the part of the public in the territory in which the earlier trade mark is protected. The likelihood of confusion includes the likelihood of association with the earlier trade mark. Moreover, under Article 8(2)(a)(ii) of Regulation No 40/94, "earlier trade marks" means trade marks registered in a Member State with a date of application for registration which is earlier than the date of application for registration of the Community trade mark.

21 According to settled case-law, the risk that the public might believe that the goods or services in question come from the same undertaking or, as the case may be, from economically-linked undertakings, constitutes a likelihood of confusion (Case T-6/01 Matratzen Concord v OHIM - Hukla Germany (MATRATZEN) [2002] ECR II-4335, paragraph 23, and Case T-129/01 Alejandro v OHIM- Anheuser-Busch (BUDMEN) [2003] ECR II-2251, paragraph 37).

22 The likelihood of confusion must be assessed globally by reference to the perception which the relevant public has of the signs and of the goods or services in question, taking into account all factors relevant to the circumstances of the case (Case T-185/02 Ruiz-Picasso and Others v OHIM - DaimlerChrysler (PICARO) [2004] ECR II-1739, paragraph 50).

23 That global assessment takes account, in particular, of awareness of the mark on the market, and of the degree of similarity between the marks and between the goods or services covered. In that respect, it implies some interdependence between the factors taken into account, so that a lesser degree of similarity between the goods or services covered may be offset by a greater degree of similarity between the marks, and vice versa (Canon, paragraph 17, and Lloyd Schuhfabrik Meyer, paragraph 19).

24 Further, the perception of marks in the mind of the average consumer of the goods or services in question plays a decisive role in the global assessment of the likelihood of confusion. The average consumer normally perceives a mark as a whole and does not proceed to analyse its various details (Case C-251/95 SABEL [1997] ECR I-6191, paragraph 23, and Lloyd Schuhfabrik Meyer, paragraph 25). For the purposes of that global assessment, the average consumer of the goods concerned is deemed to be reasonably well informed and reasonably observant and circumspect. Account should also be taken of the fact that the average consumer's level of attention is likely to vary according to the category of goods or services in question (Lloyd Schuhfabrik Meyer, paragraph 26).

25 In the present case, the similarity between the goods covered by the marks in question is not disputed by the parties. The only question under discussion is whether the Board of Appeal was entitled to consider that the marks in question were sufficiently dissimilar not to give rise to a likelihood of confusion.

Similarity between the signs

26 The global assessment of the likelihood of confusion, as far as concerns the visual, aural or conceptual similarity of the conflicting signs, must be based on the overall impression given by those signs, bearing in mind, inter alia, their distinctive and dominant components (see Case T-292/01 Phillips-Van Heusen v OHIM - Pash Textilvertrieb und Einzelhandel (BASS) [2003] ECR II-4335, paragraph 47, and the case-law cited therein).

27 Furthermore, it is settled case-law that a complex mark and another mark which is identical or similar to one of the components of the complex mark may be regarded as being similar where that component forms the dominant element within the overall impression given by the complex mark. That is the case where that component is likely to dominate, by itself, the image of that mark which the relevant public keeps in mind, with the result that all the other components of the mark are negligible within the overall impression given by it (MATRATZEN, paragraph 33, and Case T-359/02 Chum v OHIM - Star TV (STAR TV) [2005] ECR II-0000, paragraph 44). That approach does not amount, however, to taking into consideration only one component of a complex trade mark and comparing it with another mark. On the contrary, such a comparison must be made by examining the marks in question, each considered as a whole (MATRATZEN, paragraph 34).

28 At issue in the present case are, on the one hand, a mark composed of a single element which, in the light of the goods which it designates, will be perceived as the representation of a cowhide and, on the other, an earlier complex mark consisting of figurative and word elements. The figurative elements of the earlier mark consist of the representation of a cowhide in black and white covering the packaging, with stylised grass at the bottom of the carton, a farm with a little red barn near the top of the carton as well as the standardised bar code near the bottom of the carton. The word elements of the earlier mark are the words "inex", "halfvolle melk" and the abbreviation "UHT - e 1L".

29 Since the phonetic similarity of the conflicting marks is not called into question in this case, only the visual and conceptual similarities will be examined.

- Visual similarity

30 It must be noted, first of all, that the design to be perceived as a cowhide constitutes the sole element of the mark applied for.

31 In respect of the earlier mark, the cowhide design completely covers the packaging of the goods and dominates the visual impression given by the mark, as found by the Board of Appeal in paragraph 21 of the contested decision. That design constitutes a striking element of the earlier mark.

32 In that respect, the argument of the Office that the weak distinctive character of the cowhide design precludes that design from being regarded as a dominant element cannot be accepted in all circumstances. Although it is settled case-law that, as a general rule, the public will not consider a descriptive element forming part of a complex mark as the distinctive and dominant element of the overall impression conveyed by that mark (BUDMEN, paragraph 53, and Joined Cases T-117/03 to T-119/03 and T-171/03 New Look v OHIM - Naulover (NLSPORT, NLJEANS, NLACTIVE and NLCollection) [2004] ECR II-0000, paragraph 34), the weak distinctive character of an element of a complex mark does not necessarily imply that that element cannot constitute a dominant element since, because, in particular, of its position in the sign or its size, it may make an impression on consumers and be remembered by them (see, to that effect, Case T-115/02 AVEX v OHIM - Ahlers (a) [2004] ECR II-2907, paragraph 20).

33 It must none the less be pointed out that, since the comparison between marks must be based on the overall impression given by them having regard, in particular, to the distinctive character of their elements in relation to the goods or services concerned, it does not suffice, in order to find a similarity between marks, that an element essential to the visual impression of a complex mark and the sole element of the other sign are identical or similar. On the other hand, it should be concluded that there is a similarity where, considered as a whole, the impression given by a complex mark is dominated by one of its elements in such a way that the other components of that mark appear negligible in the image of that mark which the relevant public remembers, in the light of the goods or services designated.

34 In this instance, although the cowhide design constitutes an essential element in the visual impression of the earlier mark, the fact remains, none the less, that that design has only weak distinctive character in the present case.

35 For the purpose of assessing the distinctive character of an element making up a mark, an assessment must be made of the greater or lesser capacity of that element to identify the goods or services for which the mark was registered as coming from a particular undertaking, and thus to distinguish those goods or services from those of other undertakings. In making that assessment, account should be taken, in particular, of the inherent characteristics of the element in question in the light of whether it is at all descriptive of the goods or services for which the mark has been registered (see, by analogy, Lloyd Schuhfabrik Meyer, paragraphs 22 and 23).

36 In this case, it should be noted that, having regard to the goods concerned, the cowhide design cannot be regarded as highly distinctive, since that element is strongly allusive to the goods in question. That design refers to the idea of a cow, an animal known for its milk production, and constitutes an element which is unimaginative to designate milk and milk and dairy products.

37 In that respect, it is appropriate to reject the applicant's argument that in the Benelux countries that element of the earlier mark is distinctive on account of the fact that that mark is the only one in those countries to have a cowhide in black and white as the dominant element. That fact is not such as to alter the finding in the preceding paragraph concerning the weak distinctive character of the cowhide design. Moreover, in so far as that argument seeks to claim that the cowhide design of the earlier mark is highly distinctive because of the possible renown of that mark in the Benelux countries, the Court notes that the applicant has not put forward any evidence to prove that that mark enjoys such renown with the public.

38 It is also appropriate to reject the applicant's argument that to call into question the distinctive character of that cowhide design would amount to infringement of the principle under which the parties delimit the scope of the case. The absence of any challenge by the intervener of the contention that the earlier mark is the only one in the Benelux countries to bear that design in a dominant way cannot permit the inference that the intervener accepts that that element is particularly distinctive. As was found in the preceding paragraph, the fact alleged by the applicant that the earlier mark is the only one in the Benelux countries to bear the cowhide design as the dominant element is not, in itself, in the least capable of conferring on that element a particularly distinctive character.

39 The applicant's argument that the cowhide design contained in its mark is distinctive by virtue of the fact that the market for the goods in question is very competitive must also be rejected. The applicant puts forward no evidence to permit the inference that that fact is, in itself, capable of conferring a particularly distinctive character on the cowhide representation of the earlier mark.

40 Finally, in so far as the applicant seeks to claim that the cowhide design of the earlier mark has distinctive character in the light of the fact that the mark applied for, which is made up exclusively of that design, was accepted for registration by the Office, it must be observed that it is not disputed that the marks in question are not devoid of any distinctive character within the meaning of Article 7(1)(b) of Regulation No 40/94 and that they can therefore be registered. In this case, the analysis of the distinctive character of the signs in question does not form part of the assessment of the absolute grounds for refusal, but of the global assessment of likelihood of confusion. As the Office correctly points out, it is not therefore a question of determining whether the cowhide designs are devoid of any distinctive character, but of assessing the distinctive character of those designs in relation to the goods in question, for the purposes of determining whether there is a likelihood of confusion on the part of the public concerned between the marks at issue, each considered as a whole.

41 The visual comparison of the conflicting marks indicates that the overall impression given by each of those marks differs significantly. Whereas the mark applied for consists only of a representation which must be perceived, given the goods designated, as a cowhide, the earlier mark is made up, as the Office observes, of a number of figurative and word elements other than the mere representation of a cowhide, which contribute significantly to the sign's overall impression. It should be noted in particular that those elements include the presence of stylised grass at the bottom of the carton, the image of a farm with a little red barn near the top of the carton and the word element "inex". As the Office notes, the last element is a word with no obvious meaning, which should be recognised as having a much higher degree of distinctive character than the cowhide design. Since the "inex" word element contributes in a decisive manner to the overall impression given by the earlier mark, its presence does not permit the inference that the cowhide design of the earlier mark is likely to dominate, by itself, the image of that mark which the public keeps in mind.

42 In addition, it must be stated that the design which is the subject of the trade mark application is composed of a drawing different from that of the cowhide design of the earlier mark. As appears from the contested decision, the mark applied for is not an entirely obvious representation of cowhide, and the Board of Appeal found that the mark will be perceived as a representation of cowhide on account of the goods it designates.

43 For the same reason, it is also necessary to dismiss the applicant's argument that the Office contradicted itself in finding, on the one hand, that the mark against which the opposition is directed is identical to the dominant element of the earlier mark and, on the other, that the marks at issue have strong differences. First, as was observed in the preceding paragraph, the contested decision does not make a finding that the design of the mark applied for is identical to that of the earlier mark. Secondly, as was noted in paragraph 33 above, since the comparison between the marks is based on the overall impression given by them having regard, in particular, to the distinctive character of their elements in relation to the goods or services concerned, it does not suffice, in order to find a similarity, that an element essential to the visual impression of a complex mark is identical or similar to the sole element of another sign.

44 It must therefore be found that the Board of Appeal did not err in finding that the marks in question have strong visual differences.

- Conceptual similarity

45 As the Board of Appeal pointed out, there is a conceptual similarity between the marks in question on account of the fact that they call to mind the idea of a cow known for its milk production. None the less, as the Court found in paragraph 36 above, that idea has only weak distinctive character in the light of the goods in question. Where the earlier mark is not especially well known to the public and consists of an image with little imaginative content, the mere fact that the two marks are conceptually similar is not sufficient to give rise to a likelihood of confusion (SABEL, paragraph 25).

46 The Board of Appeal was therefore fully entitled to find that a conceptual similarity between the marks at issue was unlikely, in this case, to lead to a likelihood of confusion.

Global assessment of likelihood of confusion

47 It follows from the foregoing that, although the cowhide design is essential to the visual and conceptual impression given by the earlier mark, neither the significant visual differences between the signs at issue nor the weak distinctive character of the cowhide design in this case lead to the conclusion that there is a likelihood of confusion between the marks at issue.

48 Moreover, the Board of Appeal did not fail to take account of the interdependence between the factors to be taken into consideration. Neither the presence of strong visual differences between the marks in question nor the weak distinctive character of the cowhide design in this case can be offset by the fact that the goods are identical.

49 Further, the applicant's argument that the Board of Appeal should have found that the likelihood of confusion is increased by the fact that the goods in question are targeted at the general public must also be rejected. The fact that consumers have a relatively low level of attention does not, in the absence of sufficient similarities between the marks in question, and having regard to the weak distinctive character of the cowhide design in the light of the goods concerned, lead to the conclusion that there is a likelihood of confusion.

50 Accordingly, the Board of Appeal did not err in finding that the global assessment of the conflicting signs did not give rise to a likelihood of confusion.

51 It follows from the foregoing that the application must be dismissed.

Costs

52 Under Article 87(2) of the Rules of Procedure, the unsuccessful party is to be ordered to pay the costs if they have been applied for in the successful party's pleadings. Since the applicant has been unsuccessful, it must be ordered to pay the costs in accordance with the form of order sought by the Office and the intervener.

On those grounds,

THE COURT OF FIRST INSTANCE (Second Chamber)

hereby:

1. Dismisses the action;

2. Orders the applicant to pay the costs.

|

Pirrung |

Meij |

Pelikánová |

Delivered in open court in Luxembourg on 13 June 2006.

|

E. Coulon |

J. Pirrung |

|

Registrar |

President |

* Language of the case: English.