Freely Available British and Irish Public Legal Information

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback]

England and Wales High Court (Admiralty Division) Decisions

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> England and Wales High Court (Admiralty Division) Decisions >> Monford Management Ltd (Owners of the KIVELI) v Afina Navigation Ltd (Owners of the AFINA I) [2025] EWHC 1185 (Admlty) (16 May 2025)

URL: http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Admlty/2025/1185.html

Cite as: [2025] WLR(D) 273, [2025] EWHC 1185 (Admlty)

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [View ICLR summary: [2025] WLR(D) 273] [Help]

Neutral Citation Number: [2025] EWHC 1185 (Admlty)

Case No: AD-2023-000012

Case No: AD-2023-000023

IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE

KING'S BENCH DIVISION

BUSINESS AND PROPERTY COURTS OF ENGLAND AND WALES

ADMIRALTY COURT

Royal Courts of Justice, Rolls Building

Fetter Lane, London, EC4A 1NL

Date: 16/05/2025

Before :

THE HON. MR JUSTICE BRYAN

sitting with Commodore Robert W. Dorey MA RFA FIMarEST AFNI

an Elder Brother of Trinity House as Nautical Assessor

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Between :

|

|

(The Owners of the KIVELI) |

Case No: AD-2023-000012 Claimant |

|

|

- and - |

|

|

|

(The Owners of the AFINA I) |

Defendant |

|

|

And Between: |

|

|

|

AFINA NAVIGATION LIMITED (The Owners of the AFINA I) |

Case No: AD-2023-000023 Claimant |

|

|

- and - |

|

|

|

MONFORD MANAGEMENT LIMITED (The Owners of the KIVELI) |

Defendant |

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Christopher Smith KC and Francis Hornyold-Strickland (instructed by HFW LLP) for the Owners of the KIVELI

Nigel Cooper KC (instructed by MFB Solicitors) and Tatham & Co for the Owners of the AFINA I

Hearing dates: 5, 6 and 7 November 2024

Questions to Nautical Assessor 27 November 2024

Answers from Nautical Assessor 29 January 2025

Observations of parties 19 and 20 February, 6, 7, 12 and 14 March 2025

Draft Judgment sent to the parties 9 May 2025.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Approved Judgment

This judgment was handed down remotely at 10.00am on 16 May 2025 by circulation to the parties or their representatives by e-mail and by release to the National Archives.

A. INTRODUCTION

1. At about 06:01 local time (UTC + 2) on 13 March 2021, while both underway, the bulk carriers KIVELI, now renamed “PHOENIX DAWN” (“KIVELI”), and AFINA I (“AFINA I”) collided off the South coast of Greece and in a position North West of Kithira Island at approximately 36°22’N 022°42’E (“the Collision”). The Collision occurred when KIVELI turned to port as AFINA I was turning to starboard.

2. As a consequence of the Collision, the bow of KIVELI hit the port side of AFINA I’s no.4 cargo hold at an angle of approximately 90° and became embedded in the hold, immediately causing flooding, and putting AFINA I at risk of sinking. Fortunately, there were no casualties. An inspection carried out by AFINA I’s crew at 07:00 revealed that hold no. 4 was flooded, as were nos. 3 and 4 port side double bottom tanks, and that there was water in nos. 3 and 4 port top side tanks.

3. Subsequently, a tug arrived at 1600 hrs on 13 March 2021 and made fast to the bow of AFINA I in order to tow both vessels to Ormos Vatika, a bay located on the Peloponnese, Greece, near to the town of Neapolis. The vessels remained locked together for the next 20 days whilst plans were made to separate them, without further damage, so that repairs could be made.

4. The time of the Collision was 06:01 local time (UTC + 2) or 04:01 UTC. Any references below to ‘C-x’ or ‘C+x’ are calculated from this time. Times referred to below are local time unless otherwise stated.

5. This is the hearing of liability in the collision actions brought by the Owners of each vessel against the Owners of the other. The actions were consolidated with the agreement of the parties pursuant to an order of the Court dated 24 October 2023.

6. At the Case Management Conference on 30 January 2024, Cockerill J ordered that the Court would sit with one nautical assessor appointed by the Court. The nautical assessor who sat with me was Commodore Robert W. Dorey MA RFA FIMarEST AFNI, an Elder Brother of Trinity House (“Commodore Dorey”).

7. I followed the usual procedure for obtaining the advice of the nautical assessor set out by Gross J (as he was then) in The Global Mariner and the Atlantic Crusader [2005] EWHC 380 (Admlty) at [12]-[17], especially at [14]. Specifically:

(1) I ensured that counsel made any submissions they wished to make as to the questions that might be put to the assessor and, in the event, there was almost total agreement between counsel as to the questions to be asked. I then set out the questions to be asked of Commodore Dorey in a written brief to him dated 27 November 2024. The questions posed to Commodore Dorey, and his answers, are set out in Annex 2 to this judgment.

(2) Commodore Dorey provided his advice in response, in writing, on 29 January 2025, and my Clerk sent a copy to counsel on receipt so they could take instructions and provide observations on behalf of their respective clients, if so advised.

(3) The parties provided written observations to me in relation to the advice of Commodore Dorey on 19 February 2025 (AFINA I), 20 February 2025 (KIVELI) and upon each other’s observations on 6 March 2025 (KIVELI) and 7 March 2025 (AFINA I), with further submissions in relation thereto being sent to me on 12 March 2025 (KIVELI) and 14 March 2025 (AFINA I). Having considered such observations, I did not consider it necessary to seek any further advice from Commodore Dorey, and I proceeded to my judgment.

8. I would like to express at the outset my thanks to Commodore Dorey for his expertise and insightful responses to the questions posed to him.

9. The only witness that gave evidence before me was the Chief Officer of the KIVELI Mr Agriam Jay R Ejeda (“Mr Ejeda”/“KIVELI’s Chief Officer”), who was KIVELI’s Officer of the Watch (“OOW”). I address my findings in relation to Mr Ejeda, and his evidence, in due course below.

10. There were also witness statements served in respect of other witnesses. Hearsay notices were served in respect of those on behalf of AFINA I, but not those on behalf of KIVELI. However, no point was taken in that regard on behalf of AFINA I, and the parties were content for such statements to be before me, with submissions being made as to weight, where appropriate, including in the context of the fact that none of this evidence had been tested in cross-examination.

11. In this regard I had before me:-

(1) On behalf of the KIVELI, a statement of the Master, Captain Guram Chkhaidze, dated 21 May 2024, the statement of the Chief Officer Mr Ejeda, dated 30 May 2024, and the statement of the Second Officer, Mr Ryan Jose Montinola Jayme Jr, dated 30 May 2024.

(2) On behalf of the AFINA I, the statement of the Master, Captain Iurii Reizvikh, dated 14 May 2024, a statement of the Chief Officer, Mr Roman Kyselyov (“Mr Kyselyov”/“AFINA I’s Chief Officer”), AFINA I’s OOW at the time of the Collision, dated 13 March 2021, and a witness statement of Mr. Mark Paternoster (“MP1”), dated 24 May 2024, attaching a draft statement of AFINA I’s Chief Officer, dated 23 March 2021, and a draft statement of the Helmsman, Mr Vladyslav Makhmut, dated 24 March 2021.

12. I had before me agreed audio transcripts for both vessels, an agreed MADAS animated plot produced by Avenca Limited for both parties showing both vessels’ courses together with their radar display and navigational data, a NMEA Schedule of Parameter Values allowing comparison of the vessels’ data including Course Over the Ground (“COG”), heading, Speed Over the Ground (“SOG”), bearings, relative bearings and range at 15 second increments from C-60 until C+10, as well as radar flip books for each vessel showing each vessel’s radar displays at 1 minute increments.

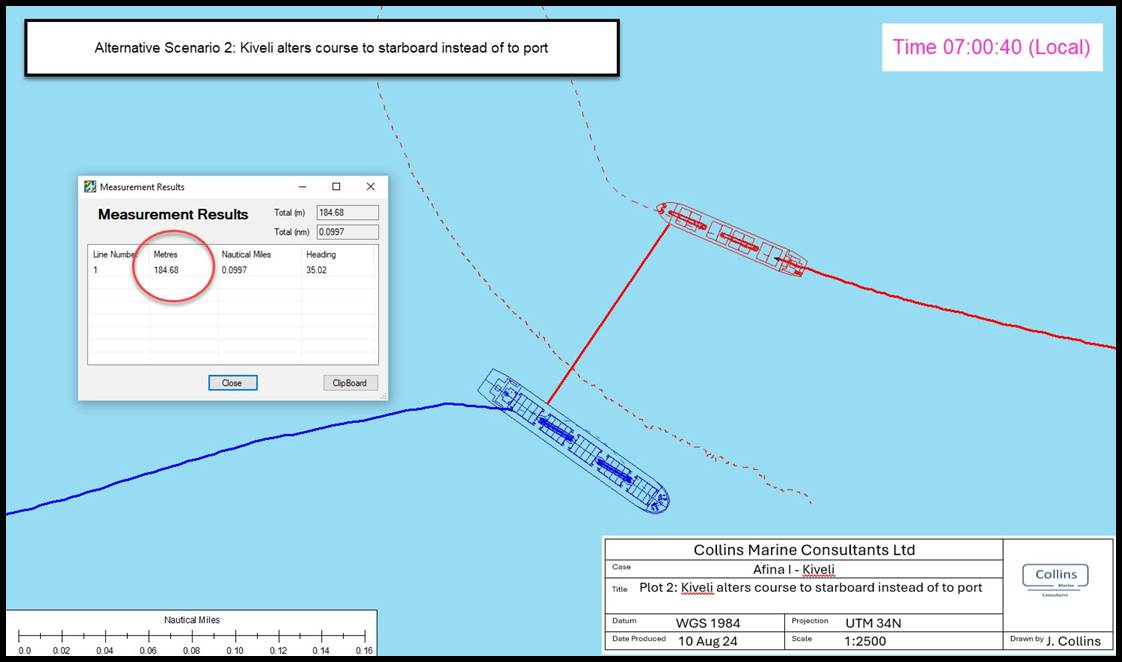

13. I attach at Annex 1 hereto, two what-if plots (that formed Annex 1 to AFINA I’s Skeleton Argument) showing what would have happened (1) if KIVELI had either held her course or (2) made a turn to starboard rather than turning to port when she did. Both plots show that there would have been no collision if KIVELI had not turned to port at this time, or had held her course.

B. LIST OF COMMON GROUND AND ISSUES

14. There was an agreed List of Common Ground and Issues before the Court, setting out common ground between the parties, and issues identified by the parties. After the hearing the parties also provided a detailed agreed Statement of Facts (the “Agreed Statement of Facts”) which I also provided to Commodore Dorey. It suffices to note at the outset, by way of overview, that the two principal issues are as to:-

(1) Whether the vessels were (at any material time) on reciprocal or nearly reciprocal courses so as to involve a risk of collision, alternatively whether there was any doubt as to whether such a situation existed, for the purposes of Rule 14 of the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea 1972 (“the Collision Regulations”).

(2) Whether the vessels were (at any material time) crossing so as to involve a risk of collision pursuant to Rule 15 of the Collision Regulations.

15. The answers to these two questions inevitably assist in relation to the Court’s assessment of navigational decisions taken by each vessel after they were in sight of each other and, it is said, there was a risk of collision. In summary:-

(1) AFINA I says that these two questions should be answered “Yes” and “No”. AFINA I says that the vessels were, at all material times, on reciprocal or nearly reciprocal courses so as to involve a risk of collision, or alternatively there was a doubt as to whether such a situation existed, for the purpose of Rule 14 (a “head-on situation”), rather than a “crossing situation” (Rule 15), and that responsibility for the Collision rests 100%, or at least 80%, with KIVELI who failed, in breach of Rules 2, 7, 8, 14, and (if applicable) 17, as well as in breach of her duty of care, to turn to starboard in order to avoid AFINA I and, instead, turned to port thereby causing the Collision. AFINA I further submits that, even if the vessels were, at any material time, to be considered as being in a “crossing situation” and AFINA I were found to be the give-way vessel, KIVELI, as the stand-on vessel for the purposes of Rule 17 of the Collision Regulations was causatively negligent because she turned to port into AFINA I instead of turning to starboard or holding her course.

(2) KIVELI says that these two questions should be answered “No” and “Yes”. In this regard KIVELI submits that at relevant times AFINA I only ever had KIVELI on her starboard side, and this was, in so far as a risk of collision existed at this time, a “crossing situation” and AFINA I was the give-way vessel, with a duty to keep out of the way of KIVELI and avoid crossing ahead of her (Rule 15) and with a duty to take “early and substantial action to keep well clear” (Rule 16), and was 100% responsible for the Collision in doing neither. As for KIVELI’s late alteration of course to port immediately prior to the Collision, it is said that this was an understandable and reasonable reaction in the agony of the moment in an attempt to avoid the danger coming from her starboard side (“even if (with hindsight) it appears that turning to port may not have been the correct response” - as it was candidly acknowledged in KIVELI’s Skeleton Argument).

C. THE WITNESSES

C.1 KIVELI’s CHIEF OFFICER (MR EJEDA)

16. Mr Ejeda had held his Certificate of Competency as a Chief Officer since 2017 (and had also been ticketed as a Master in 2020 or 2021). His statement was dated 30 May 2024, although it was stated at paragraph 39 thereof that he made his statement “during a face-to-face interview, only 11 days after the incident, while the events are fresh in my mind”. In his evidence in chief he confirmed that he did not wish to make any changes to his statement and he stated that his statement was true. He had also made a statement about 2 hours after the Collision at 08:00 on 13 March 2021.

17. Mr Ejeda was OOW of the KIVELI in the hours leading up to the Collision and at the time of the Collision. It was his obligation under Rule 5 of the Collision Regulations to maintain a proper look-out, and in the circumstances in which he found himself that burden fell upon him alone, as he was without the assistance of the watch-keepers on the Bridge, who had been given the night off by the Master following maintenance works they had been involved in during the previous day.

18. As will appear, Mr Ejeda did not keep a proper look-out, and I accept Commodore Dorey’s advice in that regard (Answers 11 and 12) that he should have acquired the contacts with other vessels, namely CAPE NATALIE and AFINA I, much earlier than he did, after which he should have taken action with a bold alteration to starboard which would have resolved the collision risk with both vessels. He did not do so, and instead made small alterations to port which were not appropriate (and I accept Commodore Dorey’s advice in this regard (Answer 6)).

19. Thereafter it is indisputable that his late decision to turn to port, as AFINA I was turning to starboard, was the immediate cause of the Collision, for if he had either maintained KIVELI’s course or turned to starboard (as he should have done whether it was a “head-on” situation or a “crossing” situation) the Collision would not have occurred (as is common ground, and as is confirmed in Commodore Dorey’s Answer 17, as well as being portrayed in Annex 1 hereto). However, as will be seen, the die was cast much earlier than that, and it was also Mr Ejeda’s failings in navigation and seamanship that were the root cause of the events that were to play out from 05:39 (C-22) to the Collision itself.

20. I found Mr Ejeda to be an unimpressive, and unreliable, witness who I am in no doubt told untruths during the course of his evidence, though not, I think, through innate dishonesty, but in a clumsy attempt to cover up his all too obvious failure to follow the “Master’s Standing Orders (A) Guidance for Master’s Standing Orders for Bridge Watch at Sea” (the “Master’s Standing Orders”) and the Master’s handwritten “Night Orders” (the “Night Orders”) as well as his failings in his watch keeping and associated failings in navigation and seamanship. However, as will be seen, he nevertheless made what I consider to be important admissions that shed light on the shortcomings in his navigation and seamanship, and what can only be described as a cavalier approach to compliance with the Collision Regulations, if not a positive disregard of the same, despite his professed familiarity with such Regulations.

21. The Master’s Standing Orders for KIVELI provided, amongst other matters, as follows:-

“Mobile phones shall not be used in any circumstances while on watch. They must be left in the cabin”.

22. The Night Orders for KIVELI for 12 March 2021 (signed by Mr Ejeda when he came on watch) provided, amongst other matters, as follows:-

“Follow master’s standing order

Keep a sharp lookout, give a wide CPA, avoid close quarter situation

follow the COLREG’S

…

Call me in advance when your [sic] in doubt”

23. In the trial bundle there was a transcript of what could be heard by way of sounds from the microphones on the Bridge of the KIVELI on the watch up to the time of the Collision. At 04:37:25 and 04:43:31 (adjusted to UTC +2), the transcript states, “audio of what sounds like a video clip of child laughing” and at 04:53:19 the transcript states, “audio of what sounds like video clip of baby and mother playing”. From listening to that audio myself, those are accurate descriptions of what can be heard.

24. Instead of Mr Ejeda admitting the obvious, namely that he had his cell phone or other media device on the Bridge (contrary to the Master’s Standing Orders and the Night Orders) and was either listening to such video clips or actually engaging with whoever was making those sounds remotely, Mr Ejeda suggested that he did not have a mobile and possibly it was the Second Officer who had stayed on the bridge at the end of his watch at back of the chart room to do some paperwork.

25. When it was pointed out that this meant that the Second Officer would have had to have had his mobile with him whilst on watch (which would be contrary to the Master’s Standing Orders and the Night Orders), Mr Ejeda then suggested that the Second Officer might have gone and got his phone at the end of his watch and come back. The real difficulty with all of this (quite apart from its inherent implausibility) is that the third clip at 04:53:19 is over 50 minutes since Mr Ejeda came on watch, and it is inherently improbable that he was other than alone at that time.

26. Mr Ejeda also accepted that had the Second Officer been on the Bridge using his phone after the end of his watch, Mr Ejeda, as OOW, should have reprimanded the Second Officer, and should have told him to take his phone off the Bridge. The reality, I am sure, is that this was all an untruth on the part of Mr Ejeda in a clumsy attempt to deny that he was in breach of the Master’s Standing Orders and the Night Orders (quite apart from the distraction that such activities would have represented whilst he was alone, at night, in the dark, and with sole responsibility for keeping a proper look-out).

27. This was not, I am satisfied, the only series of untruths told by Mr Ejeda. I am also sure that other examples included attempts to suggest that he was acquiring vessels on AIS when he was not, his apparent failure to know what the look ahead cone on the ECDIS was for, and his alleged lack of recollection that he did not acquire either CAPE NATALIE or AFINA I as targets on ECDIS (despite his earlier admission that he was not monitoring AFINA I using his ECDIS display).

28. There was then an unedifying series of explanations (such as they were intelligible) as to why the microphones catch Mr Ejeda singing on the Bridge very shortly before the Collision. In this regard the transcript of the microphones on the Bridge catch him “very soft singing and humming” at 05:51 and 05:53 which he himself accepted rather suggested he was not really alive to the risks posed by AFINA I, yet when it was put to him that he was still singing, and singing “will shelter you” at 05:57:51, Mr Ejeda then said this singing was to “release my worry about the situation”, only for him then to say that “I’m singing on that time because I know Afina I was already pass clear my starboard side”, a series of very different answers in very short order.

29. I am in no doubt at all that Mr Ejeda’s singing was a reflection of his lack of appreciation of the risk of collision, which may well be why, when he finally woke up to such risk, he did precisely what he should not have done, which was to turn to port. It is also notable that the singing, “will shelter you” was only seconds before the Chief Officer of the AFINA I called on the VHF, “Kiveli Kiveli Afina I, Kiveli Kiveli Afina I” to which there was no response from Mr Ejeda, with a further call 9 seconds later, “Kiveli, Kiveli Afina I”, getting the response from Mr Ejeda: “I am altering my course to portside. Altering course my to portside now”.

30. This provoked the immediate (and no doubt shocked) response from the Chief Officer of AFINA I, “No Portside. No Portside. Ok? Ok?” (per KIVELI bridge audio transcript), which, despite suggestions to the contrary on KIVELI’s behalf, was clearly AFINA I’s Chief Officer saying (in effect, and rightly), “Do not turn to port. Do not turn to port. Do you understand? Do you understand?” (In fact the AFINA I bridge audio transcript is even clearer still in terms of what it captures as to what was actually said, “no port side, no port side … ok, ok, no port side”).

31. However, notwithstanding the untruths that were told by Mr Ejeda, there was much in Mr Ejeda’s evidence that sheds real light both as to the factual position, and as to his approach to seamanship and navigation on the night in question, and I accept such evidence (variously) as it either has the ring of truth about it, or amounts to admissions against interest or on the basis that it is supported by other evidence:-

(1) He acknowledged that if he felt it appropriate he would not follow the Collision Regulations.

(2) His evidence was that he did not acquire either CAPE NATALIE or AFINA I as targets on his ECDIS system at any time.

(3) His evidence was that he acquired CAPE NATALIE and AFINA I as targets on his radar at 05:47.

(4) His agreement that looking at the position of each of the CAPE NATALIE and AFINA I at 05:45, KIVELI had room to turn to starboard to avoid them.

(5) He acknowledged his willingness to countenance passing CAPE NATALIE and AFINA I at a distance of 200-300 metres in what he accepted was a close quarters situation and was “not a safe passing distance” and which he acknowledged was also a breach of the Master’s Standing Orders and the Night Orders.

(6) He countenanced such a passing with CAPE NATALIE despite the fact that, “when I first visually saw CAPE NATALIE I remember seeing her two masthead lights in a straight line and both her port and starboard lights” (a classic “head-on” situation within Rule 14(b) by reference to what he could see (KIVELI’s Chief Officer’s statement at paragraph 27)).

(7) He was also countenancing (at 05:48hrs) passing AFINA I starboard to starboard at a mere 200 metres (evidence volunteered in re-examination).

(8) He acknowledged that when he turned to port he was in breach of the Collison Regulations.

C.2 AFINA I’S CHIEF OFFICER (MR KYSELYOV)

32. KIVELI would have wished to cross-examine AFINA I’s Chief Officer Mr Kyselyov. However, he was unable to attend for cross-examination in circumstances where he no longer works for AFINA I and is in occupied Ukraine. Mr Smith KC, on behalf of KIVELI, indicated that he accepted that the draft statement of the Chief Officer of the AFINA I recorded what he had told Mr Paternoster. For its part KIVELI made submissions as to the Chief Officer of AFINA I, and his evidence, in its Closing Note to which I have had regard.

33. I bear well in mind that the Chief Officer of AFINA I did not give oral evidence and so it was not possible for his evidence to be tested in cross-examination. To the extent that there are inconsistencies between his recollection and the VDR data I do not consider that such inconsistencies were deliberate or designed to mislead or call into question the veracity of his evidence, not least having regard to the navigation of the AFINA I as a whole as addressed in due course below. In such circumstances, I have accepted his evidence where consistent with the other evidence before me and the advice of Commodore Dorey as to AFINA I’s navigation. Where there are inconsistencies between the Chief Officer’s evidence and the VDR data I have proceeded on the basis of the VDR data.

34. Apart from the parties’ respective submissions as to the navigation of the AFINA I (which inevitably engage the actions or inactions of AFINA I’s Chief Officer over the time period leading up to the Collision), one factual issue that remained between the parties in relation to the evidence of AFINA I’s Chief Officer was whether, as he said he did, he used AFINA I’s Aldis lamp to signal KIVELI at 05:54. This is but one small aspect of the evidence before me, and ultimately nothing turns on it given the other evidence in respect of this very same time period (which speaks for itself and in volumes), however I find, on balance of probabilities, that he did so.

35. My reasons for so finding are as follows. First, this was recorded in the deck log at 07:02. It would be a serious allegation to suggest that such entry was falsely made (which in reality underlies KIVELI’s submission), and such serious allegation lacks substantiation. Secondly, this was the Chief Officer’s evidence at paragraph 35 of his draft statement which KIVELI accepts records what AFINA I’s Chief Officer told Mr Paternoster. I see no reason or justification to conclude that his statement was an untruth in circumstances where such action and conduct is entirely consistent with the fact that he was clearly concerned, contemporaneously, about KIVELI’s navigation, and in this regard it is he who contacted KIVELI shortly thereafter on the VHF. In such circumstances there was neither reason nor need to make such a statement unless it is what occurred. I do not consider that the fact that nothing is caught on AFINA I’s bridge audio takes matters any further. It is not possible to draw any conclusions from that. Thirdly, it was AFINA I’s pleaded case that the Aldis lamp was used, and it is notable that that was not challenged at the time by KIVELI. Fourthly, the fact that KIVELI’s Chief Officer did not see the flash of the Aldis lamp (evidence which I accept) is entirely consistent with the evidence, and my conclusion, that Mr Ejeda was not keeping a proper look out.

D. THE FACTS

D.1 INTRODUCTION

36. Following the oral hearing the parties liaised with each other and produced an agreed statement of facts (the “Agreed Statement of Facts”) which was provided to the Court on 27 November 2024, and which form the basis of this Section. The Agreed Statement of Facts includes agreement (for example) as to what individuals have said.

37. What follows is subject to the findings I have made as to the truth or otherwise of particular statements that have been made (for example Mr Ejeda saying that he was monitoring vessels on ECDIS). The parties also made clear that whilst the Agreed Statement of Facts sets out those facts which have been agreed by the parties, it is intended to be considered with the oral and written submissions made by each party and is not intended to amend either party’s case. I have borne that distinction well in mind.

D.2 THE VESSELS

38. Each of the vessels is a bulk carrier. AFINA I is registered in Malta with a home port of Valetta. KIVELI (now re-named “PHOENIX DAWN”) is registered in Liberia with a home port of Monrovia.

39. AFINA I has a length overall of 138.6 metres, breadth of 20.50 metres and a gross tonnage of 9,997 tons. Her main engine develops 5833 horsepower (4,350kW). Her draught is about 7.9 metres and her maximum draught for the voyage was 8.1m. At the time of the Collision she was enroute from Novorossiysk to Bilbao, Spain with a cargo of hot briquetted iron.

40. KIVELI has a length overall of 193.84 metres, breadth of 27.6 metres and an even keel draught of 10.9 metres at the time of the Collision. The main engine has a power output of 10,625 kW. KIVELI was carrying a cargo of approximately 36,100mt of rock phosphate from Casablanca to Bulgaria.

41. Both vessels were displaying two white masthead lights, their red and green side lights, and a white stern light. Masthead lights must be visible from a minimum of 6 miles and side lights from a minimum of 3 miles. In practice, they are visible from a greater range in good visibility. In the present case sunrise was at 06:42 such that the Collision occurred while it was still dark but in circumstances where visibility was good.

D.3 THE VESSELS’ INTENDED COURSES AND THE LOCATION OF THE COLLISION

42. KIVELI was on passage from Casablanca, Morocco to Varna, Bulgaria via Istanbul. Her course was such that prior to the Collision she was approaching the Stenó Elafonísou Strait from a south westerly direction.

43. The Chief Officer of KIVELI describes her course from about 04:00 on 13 March 2021 starting at paragraph 18 of his Witness Statement. From waypoint 14 to waypoint 15 KIVELI was heading between 79-80° from 05:00 until around 05:22 when the Chief Officer says he made a course alteration to c.077°T to “place the vessel on the planned track between waypoints 14 and 15”.

44. AFINA I was enroute from Novorossiysk to Bilbao and her voyage took her through the Stenó Elafonísou Strait, which she entered at about 03:50. AFINA I made a number of course alterations to keep a safe distance from the CAPE NATALIE before, having passed clear of the Strait and moved into the Western Approaches to Stenó Elafonísou at c.05:10, she altered course between 05:13:18 to 05:17:00 on to a heading of about 242°T. AFINA I’s intended course was 256°T.

D.4 THE WEATHER AND SEA CONDITIONS

45. Prior to and at the time of the Collision, there was a Westerly wind Beaufort force 3. The sea state was slight with a swell of approximately 0.5 metres. There was no appreciable current at the time of the Collision. It is not suggested that the weather conditions played any part in the events that occurred.

D.5 THE VESSELS’ WATCHKEEPING AND COURSE PRIOR TO THE COLLISION

46. On 12 March 2021, KIVELI’s Master, Captain Guram Chkhaidze, gave the duty watchkeepers the night off (after they had been involved in maintenance work during the day) so that each watchkeeping officer on KIVELI was on the bridge on their own. The Chief Officer, Mr. Ejeda, came on watch for the 04:00 to 08:00 watch at about 04:00 and relieved the Second Officer. The Chief Officer says (but this is in issue) that he was navigating KIVELI using ECDIS and the X-band radar.

47. As already noted, the Night Orders of the Master of KIVELI for 12 March 2021 provided inter alia:

“(a) Follow Master’s standing orders;

(b) Keep a sharp lookout give a wide CPA avoid close quarter situation;

(c) Follow the ColRegs;

…

Call me anytime when your in doubt.”

48. The night orders of the Master of AFINA I for 12 March 2021 provided inter alia:

“(a) Keep navigation and radio watch acc. ColReg and GMDSS …;

(b) Keep course acc passage plan;

(c) Keep safety distance to other vessels;

(d) Call master in case of any doubt.”

49. AFINA I’s Chief Officer, Roman Kyselyov, says, in his draft witness statement at [14], that he was also doing the 04:00 to 08:00 watch and relieved the Second Officer at shortly before 04:00. According to the draft witness statement of Mr. Makhmut, the duty watchkeeper, he was also on watch.

50. At around 05:30 KIVELI’S Chief Officer says he started “to take particular note of the target echoes of” AFINA I and CAPE NATALIE on “the radar and their AIS signals as shown on the ECDIS”. At this time, AFINA I was on a heading of 245.2° with a COG of 244.7° and a SOG of 12 knots at a distance of about 12.135 nm from KIVELI. KIVELI at this time was on a heading of 77.4° with a COG of 77.6° and a SOG of 11.85 knots. The difference between their reciprocal headings was 12.2° (257.4°-245.2°) and between their reciprocal COGs was 12.9° (257.6° - 244.7°). AFINA I was bearing 2.8° off the Port bow of KIVELI. KIVELI was bearing 3.7° off AFINA I’s Starboard bow.

51. KIVELI’s Chief Officer says that when he first visually saw CAPE NATALIE, he saw her two masthead lights in a straight line and both her port and starboard lights and also says (but which is not accepted by AFINA I) that he could see from the ECDIS that she was passing safely ahead.

52. At 05:38 (C-23) AFINA I’s Chief Officer says he first observed KIVELI on her radar at a distance of around 8.67 nm. The Chief Officer considered that the vectors of the two vessels meant that they would pass green to green with a CPA of 0.213 nm. The Chief Officer says that he was monitoring KIVELI by radar and visually and that KIVELI was showing predominantly a green side light but on occasions her green and red side lights as the two vessels independently yawed ([28] of his statement) (although this is not accepted by KIVELI).

53. On behalf of AFINA I, Mr. Paternoster says, when he interviewed AFINA I’s Chief Officer, the latter said he could also see KIVELI’s masthead lights (at [10] of MP1). At that distance of 8.67 nm the time was 05:38:45 (C-23), AFINA I was on a heading of 249.9°T and a COG of 250.2°T and an SOG of 11.9 knots. KIVELI at this time was on a heading of 77°T with a COG of 77.3°T and an SOG of 11.78. The difference between their reciprocal headings was 7.1° (257°-249.9°) and between their reciprocal COGs was 7.1° (257.3°-250.2°). AFINA I was bearing 2.3° off the Port bow of KIVELI. KIVELI was bearing 4.9° off AFINA I’s starboard bow.

54. By about 05:39 (C-22), AFINA I was on a heading of about 250.2°T and with a COG of 250.2°T. and SOG of 11.9 knots (having altered her heading to starboard from a heading of about 245.2 degrees at c. 05:30). KIVELI was on a heading of 77.2°T with a COG of 77.1°T and SOG of about 11.77 knots. The reciprocal between the vessels’ respective headings at this time was 7° and the difference between their COG was 6.9°. According to AFINA I’s AIS tracker, the CPA was 0.213 nm and Time to Closest Point of Approach (“TCPA”) was 22:02 minutes and the range was 8.688 nm. AFINA I was bearing 2.1° off the Port bow of KIVELI.

55. At this time, at 05:39 (C-22):

(1) The OLYMPOS SEAWAY was travelling at more than 20 knots and therefore overtaking AFINA I, passing clear astern of AFINA I;

(2) The CAPE NATALIE was approaching KIVELI ahead of AFINA I and fine off her starboard bow;

(3) The COSCO SAGITARIUS was shaping to pass KIVELI red to red;

(4) THE NORDAUTUMN was approaching KIVELI from astern;

(5) The AS CARELIA had overtaken KIVELI to starboard of her.

56. While KIVELI’S Chief Officer says he was observing AFINA I by radar at 05:30, KIVELI first particularly observed AFINA I visually and by radar at about 05:45 (C-16) when KIVELI was on a heading of 077.3° true with a COG of 077.4° and an SOG of approximately 11.7 knots. KIVELI was 5.6 degrees on AFINA I's starboard bow and AFINA I was on a heading of about 250°T with a COG of 250.9° and an SOG of about 11.9 knots. AFINA I was showing a starboard aspect and her bearing was opening to starboard such that she was shaping to pass KIVELI at a distance of approximately 0.25 miles. The reciprocal between the vessels’ respective headings was 7.3°T (257.3°- 250°) and between their COG 6.5°T (257° - 250.9). According to AFINA I’s AIS tracker, the CPA was 0.233 nm the TCPA was 16:17 minutes and the range was 6.379 nm. AFINA I was bearing 1.7° off the Port bow of KIVELI.

57. By 05:45 AFINA I’s Chief Officer says he was monitoring both KIVELI and CAPE NATALIE as CAPE NATALIE was directly ahead of AFINA I and shaping to pass KIVELI green to green but with a small passing distance ([29] of the Chief Officer’s statement).

58. At 05:45:

(1) The OLYMPOS SEAWAY was astern of AFINA I, overtaking her on a diverging heading with a lateral separation of nearly 1 nm;

(2) The CAPE NATALIE was directly ahead or nearly ahead of AFINA I;

(3) The COSCO SAGITARIUS had passed KIVELI red to red;

(4) THE NORDAUTUMN was approaching KIVELI from astern on her port side;

(5) The AS CARELIA had overtaken KIVELI to starboard of her.

59. Between 05:45 (C-16) and 05:55 (C-6), KIVELI made two minor alterations to port steadying onto a heading initially of 075° and then 074° by 05.53:00 (C-8:00). KIVELI commenced her turn just before 05:47 (her rudder angle starts to move to port at about 05:46:52, see the Agreed Animated Plot).

60. The ARPA on KIVELI shows that three targets were manually acquired at 05:47:27 (see the Agreed Animated Plot). At that time only the data for target No. 1 (CAPE NATALIE) was displayed. At 05:47:42 the data for targets No. 2 and 3 (AFINA I and OLYMPOS SEAWAY) was displayed (Agreed Animated Plot). At 05:47:57 the alarm was activated for CAPE NATALIE (her vector line goes red) and at 05:49:10 the alarm was active for AFINA I (Agreed Animated Plot). KIVELI’s radar alarm was, at some point, muted.

61. At around 05:49 the CAPE NATALIE altered course to port, thereby increasing the passing distance (green to green) between her and KIVELI. By 05:50 KIVELI’s CPA/TCPA alarm was for AFINA I only.

62. By about 05:49 (C-12) KIVELI was on a heading of 075.3°T with a COG of 75.7° and an SOG of 11.64 knots. AFINA I was on a heading of 249.9°T with a COG of 250.8° and a speed of 11.8 knots. The difference between the reciprocal headings of the Vessels was 5.3° (255.2°- 249.9°) and between their COG was 4.9° (255.7°-250.8°). According to AFINA I’s AIS tracker, the CPA was 0.252 nm, the TCPA was 12:26 minutes and the range was 4.859 nm (Agreed Animated Plot). According to KIVELI’S ARPA tracker the CPA was 0.21 nm, the TCPA was 12:10 minutes, and the range was 4.81 nm. AFINA I was bearing 1° off the starboard bow of KIVELI and would have been able to see both her sidelights. KIVELI was bearing 6.4° off the starboard bow of AFINA I and would have been able to see her green sidelight but not her red sidelight.

63. In his witness statement, the Chief Officer of KIVELI stated that:

(1) At 05:45 (C-16), he saw AFINA I visually and on the radar. He believed that she was at a range of about 3 miles and very fine to port - 1 to 2 degrees to port and that he could see both AFINA I’s masthead lights and her green starboard light (statement at [29]).

(2) At 05:50 (C-11) he saw the masthead lights and starboard light of AFINA I fine to starboard (about 2 degrees to starboard) and that he noted on radar that the CPA was about 2 cables (c. 0.2 nm) (statement at [31]).

64. At 05:51 (C-10), the Chief Officer on board AFINA I was continuing to monitor KIVELI visually and on the radar. AFINA I was heading 250.2°T with a COG of 251.4° and an SOG of 11.8 knots. KIVELI’s heading was 75.4°T with a COG of 75.6° and an SOG of 11.6 knots.

65. KIVELI’S ARPA radar gave a CPA of 0.23 nm, the TCPA was 10:03 minutes and the range was 4.04 nm (see the Agreed Animated Plot). The difference between the two vessels’ reciprocal headings was 5.2° (255.4°-250.2°) and between their COG was 4.3° (255.6° - 251.3°). AFINA I was bearing 1.5° off the starboard bow of KIVELI and would probably have been able to see both her sidelights. KIVELI was bearing 6.7⁰ off the starboard bow of AFINA I and would have been able to see her green sidelight but not her red sidelight.

66. At about 05:51 (C-10), the Chief Officer of AFINA I says he believed that KIVELI was aware of both AFINA I and CAPE NATALIE and expected that KIVELI would alter course to starboard to pass AFINA I red to red when abeam of CAPE NATALIE (which at that time was shaping to pass KIVELI green to green) (see the Chief Officer’s witness statement at [32]). The AS CARELIA was passing AFINA I port to port with a CPA of 0.946 nm and at range of 1.012 nm, nearly abeam of her.

67. By 05:53:45 (C-8:15) KIVELI came further to port to a heading of about 74.2°T with a COG of 75.2° and an SOG of 11.62 knots. AFINA I was on a heading of 250.1°T with a COG of 251.7° and an SOG of 11.8 knots. The reciprocal between the vessels’ headings at this time was 4.1° (255.2° - 250.1°) and between their COG was 3.5°. According to KIVELI’s ARPA radar, the CPA was 0.29 nm, the TCPA was 6.4 minutes and the range was 3.42 nm (see the Agreed Animated Plot). By 05:53:45 when KIVELI had completed her two alterations to port, AFINA I was bearing 2.9° off the starboard bow of KIVELI and KIVELI was bearing 8.1° off the starboard bow of AFINA I.

68. At approximately 05:54 (C-7), the Chief Officer of AFINA I says he used the vessel’s Aldis lamp to signal five short and rapid flashes in the general direction of the bridge of KIVELI (as I have found he did). At this time, KIVELI’s ARPA radar showed the distance between the two vessels was 3.28 nm (see the Agreed Animated Plot). In other words, well within the range at which KIVELI should have seen AFINA I’s light signal if AFINA I had made one and KIVELI had been keeping a proper lookout. The evidence of KIVELI’s Chief Officer is that he did not see any flashes (I accept that evidence but my finding is that that is because he was not keeping a proper look-out, as already addressed). There is no sound associated with the use of the Aldis Lamp recorded in any of the bridge microphones on board AFINA I.

69. At approximately 05:55 (C-6), the CAPE NATALIE passed clear of KIVELI off her starboard bow (see the Agreed Animated Plot). At this time, KIVELI was on a heading and COG of 74°T and an SOG of 11.59 knots and AFINA I was on a heading of 250°T with a COG of 251.9° and an SOG of 11.8 knots. The difference between the vessels’ reciprocal headings was 4° (254°-250°) and between their COG was 2.1° (254°-251.9°). KIVELI’S ARPA radar identified that the CPA was 0.27 nm, the TCPA was 6.4 minutes and the range was 2.51 nm (see the Agreed Animated Plot). AFINA I was bearing 5.3° off the starboard bow of KIVELI and KIVELI was bearing 9.3° off the starboard bow of AFINA I. It is at this time that the Chief Officer of KIVELI says that AFINA I’s bearing had opened 5 to 10 degrees to starboard, her range was about 2.4 miles and AFINA I was passing down KIVELI’s starboard side with a CPA of about 2 cables (statement at [32]).

70. At 05:56 (C-5), AFINA I was on a heading of 252°T having commenced a slow turn to starboard, with a COG of 251.2°T and an SOG of 11.8 knots. KIVELI was on a heading of 73.9°T with a COG of 74.2° and a speed of 11.59 knots. The difference between the vessels’ respective headings was 1.9° (253.9°-252°) and between their COGs was 3° (254.2°-251.2°). According to KIVELI’s ARPA radar, the CPA was 0.27 nm, the TCPA was 5.1 minutes and the range was 2.04 nm (see the Agreed Animated Plot). AFINA I was bearing 6.7° off the starboard bow of KIVELI and KIVELI was bearing 10.1° off the starboard bow of AFINA I.

71. AFINA I continued her series of alterations to turn to starboard at this time such that by 05:57 (C-4) she was on a heading of 259.8°T with a COG of 258.7°T and an SOG of 11.6 knots. At 05:57, KIVELI was on a heading of 74.1°T and COG of 73.9°T and an SOG of 11.5 knots. The difference between the vessels’ reciprocal headings at this time was 5.7° (254.1° - 259.8°) and between their COG was 4.8° (258.7° - 253.9°). At this time KIVELI’s ARPA radar recorded the vessels’ CPA as 0.26 nm to starboard and her TCPA as being 4.2 minutes (see the Agreed Animated Plot). At this time, AFINA I’s AIS tracker recorded the vessels’ CPA as 0.220 nm and her TCPA as being 4.3 minutes. AFINA I was bearing 8.0° off the starboard bow of KIVELI and KIVELI was bearing 2.3° off the starboard bow of AFINA I.

72. By approximately 05:59:45 (C-1:15) AFINA I was on a heading of 284.9°T with a COG of 280.8° and an SOG of 11.2 knots. The Chief Officer of AFINA I says his intention was to pass KIVELI red to red in accordance with Rule 14 rather than green to green (see at [35] of the Chief Officer’s witness statement). By 05:59:45 (C-1:15), KIVELI was on a heading of 74°T with a COG of 74.9° and an SOG of 11.55 knots. The difference between the vessels’ reciprocal headings had increased to 30.9°T (254 - 284.9) and between their COG was 25.9° (254.9 - 280.8). AFINA I was bearing 9.3° off the starboard bow of KIVELI, the radar ARPA of KIVELI showed that the CPA had reduced to 0.01 nm.

73. KIVELI’S Chief Officer says that at 05:57 he observed that AFINA I was making alternations of course to starboard.

(1) KIVELI’S case is that since KIVELI’s Chief Officer referred to extracts of KIVELI’S VDR when giving particular times in his statement ([39]) and, since it is agreed (following confirmation by AVENCA on 5 November 2024) that KIVELI’s VDR system time must be adjusted forwards by 1 minute and 41 seconds when compared to the times on the agreed animated plot, the time KIVELI’S Chief Officer noticed AFINA I was making alterations to starboard should in fact be 05:58:41. KIVELI’S data included in the animated reconstruction, schedules, and plots was adjusted by this amount to ensure that it was correctly aligned in time with the AFINA I VDR data, but the data viewed by KIVELI's Chief Officer would not have been so adjusted, because AVENCA made the adjustment post collision. Hence KIVELI says that the times in the Chief Officer's statement, which are based on the extracts of the VDR data he reviewed, need to be adjusted by the same amount to bring them into line with the animated reconstruction, schedules, and plots. KIVELI points to the fact that when the time of the agreed plot is 05:57:00 the time on KIVELI’s radar is 05:56.

(2) AFINA I does not accept that the times in KIVELI’s Chief Officer’s statement do need to be adjusted as alleged. KIVELI’s Chief Officer does not explain which extracts of the VDR he was viewing for the purposes of his witness statement. To the extent that he was looking at the times shown on KIVELI’s radar display, those times are live times taken from the vessel’s GPS feed rather than from the VDR system time and would not be subject to the need for adjustment described above. Further as agreed above, AFINA I had in fact commenced her turn to starboard by 05:57. AFINA I points also to the fact that Box 12 in Part I of KIVELI’s Collision Statement of Case admits KIVELI’s Chief Officer noticing AFINA I altering course to starboard on the radar and visually at about 05:56.

74. According to AFINA I’s VDR transcript, about 05:59:35 (C-1:25), AFINA I contacted KIVELI by radio on VHF channel 16. During the six minutes prior to the radio call from AFINA I, the audio transcript of KIVELI records occasional very soft singing and humming and, immediately before the radio call from AFINA I, records the words, “will shelter you” being sung. I have already addressed such matters above and made associated findings. AFINA I’s Chief Officer also says that at C-5 he ordered the helmsman of AFINA I to “make a number of course alterations to starboard” (although there is no record of this in the agreed transcript for AFINA I).

75. The Chief Officer of KIVELI switched to manual steering at 05:59:40, and commenced a hard turn to port (see the Agreed Animated Plot). In response to AFINA I’s radio call, KIVELI’s Chief Officer responded “I am altering my course to portside. Altering course my to portside now”, to which AFINA I’s Chief Officer immediately responded, “no port side, no port side … ok, ok, no port side” (AFINA I transcript) or “no port side no port side … ok? ok?” (KIVELI transcript). Thereafter KIVELI continued her hard turn to port.

76. Prior to AFINA I commencing her series of alterations to starboard at C-5 (05:55:45), according to KIVELI’S ARPA tracker, the vessels would have passed green to green with a CPA of 0.26 nm (481.5 m) and a TCPA of 5.11 minutes (see the Agreed Animated Plot).

77. Prior to KIVELI making any alteration to port at 05:59:40 (C-1:20), by altering course to starboard at 05:55:45 (C-5:15) AFINA I reduced the CPA between the vessels from 0.26 nm (481.5 m) to 0.01 nm (18.52 m) (see the Agreed Animated Plot).

78. Had KIVELI not responded to AFINA I’s alteration to starboard by turning to port but held her course or made a turn to starboard at that time, the vessels would have passed close to each other but would not have collided. Specifically:

(1) If KIVELI had maintained her course rather than turning to port, then at 06:01 AFINA I would have passed clear of KIVELI with a distance of about 66.44 metres between them (see Annex 1).

(2) If KIVELI had turned to starboard at 06:00 instead of to port then a distance of about 185m would have opened up between the vessels and they would have passed red to red (see Annex 1). If KIVELI had turned to starboard sooner, then the distance between the vessels would have been greater.

79. At the moment of contact, AFINA I was heading 293.4°T. The bow of KIVELI hit the port side of AFINA I’s no. 4 cargo hold at an angle of approximately 90° and became embedded in the hold immediately causing flooding and putting AFINA I at risk of sinking.

80. Neither vessel made any sound signals.

D.6 FURTHER FACTUAL FINDINGS

81. I make various further factual findings in Section F below.

E. THE COLLISION REGULATIONS

E.1 APPROACH TO CONSTRUCTION OF THE COLLISION REGULATIONS

82. The text of the Collision Regulations, as implemented under English law, is found in Merchant Shipping Notice MSN 1781 (M & F).

83. The proper approach to the construction of the Collision Regulations was common ground between the parties (although their construction was not), and I was referred to [37] to [44] in the speech of Lords Hamblen and Briggs JJSC in The Ever Smart [2021] 1 WLR 1436, in which the following propositions were laid down in relation to the construction of the Collision Regulations:-

(1) As an International Convention, the Collision Regulations should be interpreted by reference to broad and general principles of construction rather than any narrower domestic law principles.

(2) Such broad and general principles include the general rule of interpretation that they should be interpreted in good faith in accordance with the ordinary meaning to be given to terms of the treaty in their context and in light of their object and purpose.

(3) The object and purpose of the Collision Regulations is to promote safe navigation and specifically the prevention of collisions at sea.

(4) The international character of the Collision Regulations and the safety of navigation means that they must be capable of being understood and applied by mariners of all nationalities, of all types (professional and amateur), in a wide range of vessels and in worldwide waters.

(5) They should accordingly be interpreted in a practical manner so as to provide clear and readily ascertainable navigational rules capable of application by all mariners. They are meant to provide international “rules of the road”.

84. In relation to (3) above (the object and purpose of the Collision Regulations being to promote safe navigation and specifically the prevention of collisions at sea) Lords Briggs and Hamblen quoted, at [40], what was said by Sheen J in The Maloja II [1993] 1 Loyd’s Rep. 48 at pp. 50 col 2 to 51:

“The structure of the Collision Regulations is designed to ensure that, wherever possible, ships will not reach a close-quarters situation in which there is risk of collision and in which decisions have to be taken without time for proper thought.

Manoeuvres taken to avoid a close-quarters situation should be taken at a time when the responsible officer does not have to make a quick decision or a decision based on inadequate information. Those manoeuvres should be such as to be readily apparent to the other ship.”

85. In The Majola II both ships failed to take appropriate action when first aware of each other distant 11 miles. They both made alterations of course (one at 9.5 miles and one at 6 miles). Neither was appropriate and thereafter neither kept a careful radar lookout. The vessels did not see each other until they were 7 cables apart when both took action. Sheen J. observed (at p. 57):

“I do not doubt that when the ships came into sight of each other each took the action which, on the spur of the moment, seemed most likely to avoid a collision. It is irrelevant that it can now be seen that some other action would have been preferable. The officer in charge of each ship should not have found himself in such difficulty which could easily have been avoided”.

86. At p. 51 Sheen J also stated:-

“The errors of navigation which (he) regard(ed) as the most serious are those errors which are made by an officer who has time to think. At that time there is no excuse for a failure to comply with the Collision Regulations.”

87. AFINA I submits (and I agree) that this passage is particularly apt to describe the serious errors of navigation committed by KIVELI’S Chief Officer, Mr Ejeda, in relation to his willingness to countenance passing CAPE NATALIE and the AFINA I at a distance of 200-300m in what he accepted was a close quarters situation; Mr Ejeda accepting that that is “not a safe passing distance” and that it was also a breach of his Standing Orders and his Night Orders. So brazen was his conduct that he countenanced such a passing with CAPE NATALIE despite the fact that, “when I first visually saw CAPE NATALIE I remember seeing her two masthead lights in a straight line and both her port and starboard lights” (a classic “head-on” situation within Rule 14(b) by reference to what he could see) (statement at paragraph 27) and equally he was countenancing (at 05:48) passing AFINA I starboard to starboard at a mere 200 metres (evidence volunteered in re-examination). Of course AFINA I also points out that the actions of Mr Ejeda were further misplaced (and causative) when he turned to port immediately before the Collision (and, in effect, turned into the port side of AFINA I).

E.2 COLLISION REGULATIONS RELIED UPON BY THE PARTIES

88. Both parties rely on Rules 2 (Responsibility), 5 (Look-out), 7 (Risk of Collision), 8 (Action to avoid Collision), 34 (Manoeuvring and Warning Signals) and 36 (Signals to attract attention).

89. In addition:

(1) AFINA I relies on Rules 14 (Head-on Situation) and 17 (Action by Stand-on Vessel).

(2) KIVELI relies on Rules 15 (Crossing Situation) and 16 (Action by Give-Way Vessel) as well as the Admiralty Sailing Directions/Traffic Regulations (“Sailing Directions”).

90. Rule 2 is a rule of general application. Rules 5, 7, and 8 apply in any condition of visibility (Rule 4). Rules 14, 15, 16 and 17 apply to vessels in sight of one another (Rule 11). Rules 34 and 36 appear in Part D (sound and light signals) and Rule 34 applies when vessels are in sight of each other.

E.2.1 RULE 2

91. Rule 2 provides:-

“ Rule 2

Responsibility

a) Nothing in these Rules shall exonerate any vessel, or the owner, master or crew thereof, from the consequences of any neglect to comply with these Rules or of the neglect of any precaution which may be required by the ordinary practice of seamen, or by the special circumstances of the case.

b) In construing and complying with these Rules due regard shall be had to all dangers of navigation and collision and to any special circumstances, including the limitations of the vessels.”

92. Rule 2 emphasises the importance of the principle of good seamanship as a general prudential rule, the intention being that the Collision Regulations should conform as closely as possible to what mariners regard as good nautical practice. The principle of good seamanship does not, however, justify disapplication of the Rules (something for which neither party contends), save in so far as may be necessary in special circumstances (see Rule 2(b)).

93. As was said by Lord Briggs and Lord Hamblen JJSC in The Ever Smart at [66] - [67]:-

“66. Attempt was made by the respondent to use rule 2 as the basis for justifying a complete disapplication of the crossing rules as a matter of construction, on the basis of an apparent conflict with the rules of good seamanship, or to treat good seamanship on its own as a sufficient alternative to the application of the crossing rules, in relation to both the questions before the court. We regard this approach to rule 2 as being misconceived. First, it is plain from rule 2(a) that compliance with the Rules is a first principle of good seamanship. The same priority appears in rule 8(a). As stated in Marsden and Gault on Collisions at Sea, 14th Edition, para 5-103, rule 2(a) “merely reminds seamen of the adverse consequences of failure to comply with the rules or with the practice of good seamanship”. In The Queen Mary (p. 341), Lord MacDermott said:

“In my opinion, it is not aimed at authorising departure from the Regulations, and I doubt if it is more than a solemn warning that compliance therewith does not terminate the ever present duty of using reasonable skill and care.”

67. Secondly, rule 2(b) builds in an inherent flexibility to meet particular dangers and special circumstances which points away from an approach which simply disapplies a rule as a matter of construction because, on particular facts, strict compliance may give rise to difficulties. Rule 2(b) contemplates not the disapplication of a rule as a matter of construction, but justifies a limited departure from its requirements, and only in particular circumstances which meet the stern test of necessity to avoid immediate danger. As stated at para 5-127 in Marsden and Gault on Collisions at Sea, 14th Edition (2016), citing The Concordia and Esther (1866) LR 1 A & E 93:

“To justify a departure from the regulations which is alleged to have been necessary to avoid immediate danger, there must be clear proof that an adherence to them would have caused such danger, and the action taken must be in accordance with the requirements of good seamanship.”

E.2.2 RULE 5

94. Rule 5 provides:-

“ Rule 5

Look-out

Every vessel shall at all times maintain a proper look-out by sight and hearing as well as by all available means appropriate in the prevailing circumstances and conditions so as to make a full appraisal of the situation and of the risk of collision.”

95. Rule 5 requires vessels to maintain at all times a proper look-out by sight and hearing as well as by all available means appropriate in the prevailing circumstances and conditions so as to make a full appraisal of the situation and of the risk of collision. It includes the use of, and proper attention to, radar where it is of assistance in keeping a good lookout - see Marsden & Gault on Collisions at Sea, 15th ed at para 7-123 and The Maloja II, [1993] 1 Lloyd’s Rep. 48 at 55.

96. The obligation to keep a proper look-out encompasses not just the requirement to look-out but also the requirement to use the information obtained from that look-out to make a full appraisal of the situation and of the risk of collision. As to what is required by the obligation to keep a proper look-out, the look-out has to be vigilant and sufficient according to the circumstances - see Marsden at para 7-130 and The Century Dawn and Asian Energy [1994] 1 Lloyd’s Rep. 138 at p. 152 (affirmed at [1996] 1 Lloyd’s Rep. 125).

E.2.3 RULE 7

97. Rule 7 provides:-

“ Rule 7

Risk of collision

(a) Every vessel shall use all available means appropriate to the prevailing circumstances and conditions to determine if risk of collision exists. If there is any doubt such risk shall be deemed to exist.

(b) Proper use shall be made of radar equipment if fitted and operational, including long-range scanning to obtain early warning of risk of collision and radar plotting or equivalent systematic observation of detected objects.

(c) Assumptions shall not be made on the basis of scanty information, especially scanty radar information.

(d) In determining if risk of collision exists the following considerations shall be among those taken into account:

(i) such risk shall be deemed to exist if the compass bearing of an approaching vessel does not appreciably change;

(ii) such risk may sometimes exist even when an appreciable bearing change is evident, particularly when approaching a very large vessel or a tow or when approaching a vessel at close range.”

98. Rule 7 requires every vessel to use all available means appropriate to the prevailing circumstances and conditions to determine if a risk of collision exists. A risk will be deemed to exist if there is any doubt. Rule 7 specifically requires the proper use of radar equipment and prohibits assumptions being made on the basis of scanty information - cf. Marsden, para 7-192 and The Oden & Pulkova [1989] 1 Lloyd’s Rep. 280.

99. So far as when a risk of collision exists, this is to be determined by reference to a non-exhaustive list of factors, which include the compass bearing of an approaching vessel not appreciably changing. Even when an appreciable change is evident, there may still be a risk of collision when approaching a vessel at close range.

100. In The Ever Smart at [55], the Supreme Court pointed out that a risk of collision will be deemed to exist if the compass bearing of an approaching vessel does not appreciably change. Rule 7(d)(i) does not make a steady compass bearing the only indicator of a risk of collision, see, for example, rule 7(a), (b) and (d)(ii) but nor is it a rebuttable presumption. Wherever it applies the risk of collision must be taken to exist.

101. In relation to Rule 7(a), and whether a risk of collision exists, I accept Commodore Dorey’s advice that a reasonably competent mariner would not consider a CPA of 0.25 nm to be a safe passing distance in the circumstances prevailing in the present case (Answer 7), and that this itself gave rise to a risk of collision under Rule 7(a) and required action to be taken under Rule 8, and (as applicable) Rule 14 or Rules 15 to 17.

E.2.4 RULE 8

102. Rule 8 provides:-

“ Rule 8

Action to avoid collision

(a) Any action taken to avoid collision shall be taken in accordance with the Rules of this Part and shall, if the circumstances of the case admit, be positive, made in ample time and with due regard to the observance of good seamanship.

(b) Any alteration of course and/ or speed to avoid collision shall, if the circumstances of the case admit, be large enough to be readily apparent to another vessel observing visually or by radar; a succession of small alterations of course and/ or speed should be avoided.

(c) If there is sufficient sea-room, alteration of course alone may be the most effective action to avoid a close-quarters situation provided that it is made in good time, is substantial and does not result in another close-quarters situation.

(d) Action taken to avoid collision with another vessel shall be such as to result in passing at a safe distance. The effectiveness of the action shall be carefully checked until the other vessel is finally past and clear.

(e) If necessary to avoid collision or allow more time to assess the situation, a vessel shall slacken her speed or take all way off by stopping or reversing her means of propulsion.

(f)

(i) A vessel which, by any of these Rules, is required not to impede the passage or safe passage of another vessel shall, when required by the circumstances of the case, take early action to allow sufficient sea-room for the safe passage of the other vessel.

(ii) A vessel required not to impede the passage or safe passage of another vessel is not relieved of this obligation if approaching the other vessel so as to involve risk of collision and shall, when taking action, have full regard to the action which may be required by the Rules of this Part.

(iii) A vessel the passage of which is not to be impeded remains fully obliged to comply with the Rules of this Part when the two vessels are approaching one another so as to involve risk of collision.”

(emphasis added)

103. Thus Rule 8 imposes a series of obligations in relation to actions to avoid a collision:-

(1) Any action taken to avoid collision must be undertaken in accordance with Part B of the Collision Regulations (that is Rules 4-19 in Sections I, II and III, Section II (Rules 11-18 being “Conduct of vessels in sight of one another”)).

(2) If the circumstances allow, any alteration in course must be positive, made in ample time and with due regard for good seamanship.

(3) Any alteration of course must if the circumstances allow be large enough to be readily apparent to another vessel observing visually or by radar, a succession of small alterations of course or speed should be avoided;

(4) Action taken to avoid a collision should be such as to result in passing at a safe distance.

E.2.5 RULE 14

E.2.5.1 THE LANGUAGE OF RULE 14

104. Rule 14 provides:-

“ Rule 14

Head-on situation

(a) When two power-driven vessels are meeting on reciprocal or nearly reciprocal courses so as to involve risk of collision each shall alter her course to starboard so that each shall pass on the port side of the other.

(b) Such a situation shall be deemed to exist when a vessel sees the other ahead or nearly ahead and by night she would see the mast head lights of the other in a line or nearly in a line and/or both sidelights and by day she observes the corresponding aspect of the other vessel.

(c) When a vessel is in any doubt as to whether such a situation exists she shall assume that it does exist and act accordingly.”

105. Rule 14 applies when two power-driven vessels are meeting on a reciprocal or nearly reciprocal course so as to involve a risk of collision, each shall alter her course to starboard so that each shall pass on the port side of the other (Rule 14(a)) (in other words, red to red).

106. It differs from the other Rules in Section II because it places equal responsibility for keeping out of the way on each of the two vessels involved.

107. Rule 14, with the requirement that both vessels turn to starboard, highlights that the Collision Regulations seek to avoid a situation where one vessel turns to port as the other turns to starboard. As is stated in Cockcroft & Lameijer, A Guide to Collision Avoidance Rules, 7th edn. at p. 75:-

“Whether power-driven vessels are meeting on reciprocal courses or crossing at a fine angle it is important that neither vessel should alter course to port. If it is thought necessary to increase the distance of passing starboard to starboard this implies there is a risk of collision. Several collisions have been caused as result of one vessel altering course to port to increase the passing distance and the other vessel turning to starboard.”

108. As it is put rather more pithily in Farwell’s Rules of the Nautical Road, 9th edn. at p. 305 (and in terms which I am satisfied is apt in relation to the (late) actions of KIVELI in the present case):-

“A sure way to produce a collision is for one vessel to obey, and the other to disobey, the rule. … The head-on rule, when obeyed by both, is so nearly collision-proof that it should come as no surprise that the large majority of collisions of this kind occur because one of the two vessels turns to port. While various reasons …may be assigned for this disregard of the rule, they all point to the same disastrous result: the vessel wrongfully turning to port collides with the other vessel that had properly turned to starboard. If this obvious cause of disaster could be impressed on the consciousness of every watchstander, cases of head-on collision at sea would become mercifully rare.”

109. A not dissimilar comment, with which I agree, and which is of relevance on the facts of the present case not only in relation to KIVELI’s late turn to port, but also its earlier small alterations of course to port between 05:46:50 and 05:47:20 (C-14) and at 05:53 (C-8)), is the comment of Commodore Dorey in Answer 6 where, after stating his opinion that KIVELI’s “small alterations of course to port appear to be intended to increase the passing distance (Closest Point of Approach (CPA)) to starboard, which implies that KIVELI’s OOW considered the existing CPA to be unsafe and that a risk of collision existed” and that it “was not appropriate to make small alterations of course to port” he stated:-

“General comment

In my experience it is unfortunately not uncommon to see vessels ‘nibble’ to port where a risk of collision exists, in order to marginally increase the passing CPA to starboard. Subject to the specific circumstances and conditions of each case, this represents poor seamanship and is contrary to the rules specifically crafted to prevent collisions at sea. Such action relies heavily on the assumption that all parties will have a similar disregard for the rules and therefore carries significant risk.”

Indicative of such inappropriate approach is also the evidence of KIVELI’s OOW that he was seeking to give AFINA I, “a little more room” (by such inappropriate “nibbling to port”).

110. The ethos of Rule 14 is consistent with the ethos of Rule 17(c) which requires that a power-driven vessel which is the stand-on vessel should not alter course to port for a vessel on her own port side.

111. A head-on situation is deemed to exist when a vessel sees the other ahead or nearly ahead and by night she could see the masthead lights of the other in a line or nearly in a line and/or both sidelights and by day she observes the corresponding aspect of the other vessel (Rule 14(b)).

112. When a vessel is in any doubt as to whether such a situation exists, she shall assume that it does exist and act accordingly (Rule 14(c)).

113. The structure of Rules 14 and 15 is such that Rule 14 takes precedence. This was acknowledged by the Supreme Court in The Ever Smart at [98(i)] when discussing a crossing situation:

“(i) the obligation on a give-way vessel to keep well clear, imposed by the crossing rules, applies wherever it is reasonably apparent to those navigating the vessel which has the other on her starboard side that the two vessels, not being head-on or overtaking, are crossing so as to involve a risk of collision (we shall call that, for short, “a crossing situation”). (emphasis added)

This was also acknowledged at [77]:

“Since they were neither head-on nor was either overtaking the other, they were therefore “crossing so as to involve a risk of collision” within the meaning of rule 15”.

(emphasis added)

114. If a vessel is in any doubt as to whether two vessels are meeting on reciprocal or nearly reciprocal courses so as to involve a risk of collision (i.e. a “head-on situation”) then she shall assume it does exist and act accordingly (per Rule 14(c)). Situations where a vessel may be in any doubt could include a fine passing or fine crossing situation (where, for example, the masthead lights of the other are in line or nearly in line but both sidelights of the other vessel are not necessarily seen).

115. Such matters arise as a matter of the application of the express words of Rule 14 (and see Hirst at p. 129). However, a number of issues emerged in argument as to the proper construction of Rule 14 on which the parties adopted fundamentally opposing positions:-

(1) Whether Rule 14(b) sets/defines what is a “reciprocal or near reciprocal course” within Rule 14(a) (the “Definitional Issue”). KIVELI submits it does (in particular relying on the comments of Sir Nigel Teare in The Apollo [2023] EWHC 328 (Admiralty), [2023] 1 Lloyd’s Rep. Plus 95 at [101] when he said “The limit of “reciprocal or nearly reciprocal” courses is set by Rule 14(b)”, also relying on what was said by Lord Briggs and Lord Hamblen in The Ever Smart at [68]), whereas AFINA I submits that Rule 14(b) does not define Rule 14(a), as Rule 14(b) is a “deeming” provision such that if one comes within it, it is a Rule 14(a) situation, but it does not define every situation that will come within the universe of Rule 14(a), which itself defines when it applies.

(2) Whether under Rule 14(b), a Rule 14(a) situation shall be deemed to exist:

(i) when by night she would see the masthead lights of the other in a line or nearly in a line or both sidelights, or

(ii) only when by night she would see the masthead lights of the other in a line or nearly in a line and both sidelights (the “And/Or” Issue”). AFINA I says the former, KIVELI the latter.

(3) Whether Rule 14(b) must be satisfied by both vessels or by reference to what one of the vessels (“a vessel”) sees (the “A Vessel Issue”). KIVELI submits the former (in particular relying on the comments of Sir Nigel Teare in The Apollo at [101] (as quoted below)), AFINA I the latter (having regard to the language of Rule 14(b) itself).

E.2.5.2 RULE 14 COMPARED TO RULE 18(a) OF THE COLLISION REGULATIONS 1960

116. Before turning to the proper construction of Rule 14, and the issues that arise as to its construction, I consider it to be of relevance to bear in mind that Rule 14 replaced, with significant changes, Rule 18(a) of the Collision Regulations 1960. Rule 18(a) of the Collision Regulations 1960 provided as follows:-

“

Rule 18

When two power driven vessels are meeting end on, or nearly end on, so as to involve the risk of collision, each shall alter her course to starboard, so that each may pass on the port side of the other. This Rule only applies to cases where vessels are meeting end on, or nearly end on, in such a manner as to involve risk of collision, and does not apply to two vessels which must, if both keep on their respective courses, pass clear of each other. The only cases to which it does apply are when each of two vessels is end on, or nearly end on to the other; in other words, to cases in which, by day, each vessel sees the masts of the other in a line, or nearly in a line, with her own; and by night, to cases in which each vessel is in such a position as to see both the sidelights of the other. It does not apply, by day, to cases in which a vessel sees another ahead crossing her own course, or, by night, to cases where the red light of one vessel is opposed to the red light of the other or where the green light of one vessel is opposed to the green light of the other or where a red light without a green light or a green light without a red light is seen ahead, or where both green and red lights are seen anywhere but ahead”.

117. It will be seen that Rule 18 of the Collision Regulations 1960 was highly prescriptive as to the circumstances in which the Rule applied. Breaking the Rule down, Rule 18 stated:-

(1) To apply to two power-driven vessels meeting end-on or nearly end-on so to involve a risk of collision.

(2) To only apply at night if both vessels were able to see both sidelights of the other vessel.

(3) Not to apply to two vessels which must, if both keep their respective courses, pass clear of each other.

(4) Not to apply at night to cases where:

(a) the red light of one vessel was opposed to the red light of the other vessel or where the green light of one vessel was opposed to the green light of the other vessel (passing); or where

(b) a red light without a green light or a green light without a red light is seen ahead (crossing); or

(c) where both green and red lights are seen anywhere but ahead.

118. Each of the restrictions at (2) to (4) no longer appear in the text of the new Rule 14. I consider that the effect of the new Rule 14 is to widen the circumstances where there will be a “head on situation” for the purpose of following the provisions in Rule 14(a), and also to apply Rule 14, by reason of Rule 14(c), to a situation were “a vessel” (that is either vessel) is in any doubt as to whether such a situation exists so that she shall assume it does exist and act accordingly (that is act in accordance with Rule 14(a) and alter her course accordingly).

119. I do not accept the submission of Mr Smith KC on behalf of KIVELI, in his oral closing submission, that the amendments from Rule 18 to Rule 14 were purely necessitated by the introduction of Rule 14(c). I consider that the intention behind what is now Rule 14 was to widen and clarify the scope of the application of Rule 14, fill any lacuna that may have existed between the old end-on rule and the crossing rule, and reduce or avoid the potential for conflicting actions by navigating officers by giving primacy to Rule 14, requiring both vessels to turn to starboard and making Rule 14 and Rule 17(c) consistent such that under both Rules turns to port are to be avoided (see Marsden at paragraph 7-320).

120. Rule 18, in contrast to Rule 14, applied to end-on or nearly end-on situations and expressly required at night that each vessel should be able to see both side lights of the other vessel. This requirement was dropped when Rule 18 was replaced by Rule 14 (subject to the And/Or Issue of what is meant by “and/or” in Rule 14(b) as addressed below).

121. The title to Rule 14 refers to “head-on” situations and in the text to “reciprocal courses” or near reciprocal courses rather than the previous “end-on”. Marsden suggests at paragraph 7-319 that under the old end-on rule a difference between courses of one point (11.5°) or more to be enough to take the situation outside the rule and a difference of a half a point (5.75°) or a little more to bring the situation within it. The inference from the text in Marsden is that a reference to vessels being on a reciprocal or nearly reciprocal course in Rule 14(a) is intended to give the rule a wider ambit than the old “end-on” rule had. In other words, a “head-on situation” applies to wider vector ahead of a vessel than the vector created by a difference of 5.75 - 6° under the old end-on rule.

122. AFINA I submits that a difference in course of 7° or thereabouts is nearly reciprocal and will be so if at night the masthead lights are in line or nearly in line or by day the vessel is presenting with a corresponding aspect. In The Lok Vivek [1995] 2 Lloyd’s Rep. 230 it appears that Clarke J considered that a difference of 8° or more may be outside the definition of reciprocal or nearly reciprocal for the purposes of Rule 14 (see at 240lhc). I note that in Farwell it is suggested that vessels will be nearly ahead if when the risk of collision arises her relative bearing is within 5-6° of the bow and recommends that borderline head-on situations should be treated as a head-on situation, which is consistent with the object and purpose of the Collision Regulations to promote safe navigation and the prevention of collisions at sea, with the purpose of Rule 14 itself, and the express inclusion of Rule 14(c).

123. As is pointed out in Farwell, one must be cautioned against harbouring unwarranted expectations regarding the ability of the human eye, or the kind of equipment typically found on tugs and fishing vessels, to discern bearings with a high degree of accuracy (p. 300). As is there stated:-

“For some vessels and their operators, errors of plus or minus one point, particularly when one or both vessels are yawing, are not unreasonable, and can be relied upon in forming a conclusion that a vessel was nearly ahead. Borderline cases, which give rise to doubt in the watchstander about whether risk of collision exists or the encounter should be treated as a head-on situation, should be resolved in accordance with Rules 7(a) and l 4(c).”